John Henry Foley

John Henry Foley | |

|---|---|

John Henry Foley in 1863, by Ernest Edwards | |

| Born | 24 May 1818 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 27 August 1874(aged 56) Hampstead, London |

| Resting place | St. Paul's Cathedral,London |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Sculpture |

John Henry FoleyRA(24 May 1818 – 27 August 1874), often referred to asJ. H. Foley,was an Irish sculptor, working in London. He is best known for his statues ofDaniel O'Connellfor theO'Connell Monumentin Dublin, and ofPrince Albertfor theAlbert Memorialin London and for a number of works in India.[1]

While much contemporary Victorian sculpture was considered lacking in quality and vision, Foley's work was often regarded as exceptional for its technical excellence and life-like qualities.[2]He was considered the finest equestrian sculptor of the Victorian era. His equestrian statue ofHenry Hardinge, 1st Viscount Hardingefor Kolkata was considered, with its dynamic pose of horse and rider, to be the most important equestrian statue cast in Britain at the time. His 1874 equestrian statue ofSir James Outram, 1st Baronetfor Kolkata was also widely praised and, like the Hardinge statue, was also considered an important symbol of British imperial rule in India.[3]Foley's pupilThomas Brockcompleted several of Foley's commissions after his death, including the statue of Prince Albert for the Albert Memorial.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Foley was born 24 May 1818, at 6 Montgomery Street, Dublin, in what was then the city's artists' quarter. The street has since been renamed Foley Street in his honour.[4]His father was a grocer and his step-grandfather Benjamin Schrowder was a sculptor.[5][6]At the age of thirteen, he followed his brother Edward to begin studying drawing and modelling at theRoyal Dublin Societyschool, where he took several first-class prizes.[1][7]In 1835 he was admitted to theRoyal Academy Schoolsin London, where he won a silver medal for sculpture.[1][7]Both brothers served as studio assistants to the sculptorWilliam Behnes.[2]Foley exhibited at theRoyal Academyfor the first time in 1839.[1]Foley's first significant commission came in 1840 with a sculpture group,Ino and Bacchusfor Lord Ellesmere.[7]Youth at a Streamexhibited in 1844 brought greater recognition and the same year he received two commissions from thePalace of Westminsterfor statues ofJohn HampdenandJohn Selden.[7]Thereafter commissions provided a steady career for the rest of his life.

Early career and recognition[edit]

In 1849 Foley was made an associate, and in 1858 a full member of theRoyal Academy of Art.[1]He exhibited at the Royal Academy until 1861 and further works were shown posthumously in 1875. His address is given in the catalogues as 57 George St., Euston Square, London until 1845, and 19 Osnaburgh Street from 1847.[8]Foley became a member of theRoyal Hibernian Academyin 1861 and an associate of the Belgium Academy of Arts in 1863.[7]

A number of works by Foley featured in theGreat Exhibitionof 1851, including the marbleIno and Bacchusand a bronze casting of aYouth at a Stream.[9]After the Great Exhibition closed, theCorporation of Londonvoted a sum of £10,000 to be spent on sculpture to decorate the Egyptian Hall in theMansion Houseand commissioned Foley to make sculptures ofCaractacusandEgeria.[10]In 1854, Foley submitted a design for the proposed monument to theDuke of Wellingtonto be sited inSt Paul's Cathedralwhich was rejected.[3]Foley's sculpture bronzeThe Norsemanwas exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1863 to considerable acclaim and represented a departure from the more traditional sculpture style of his contemporaries.[11]The art criticEdmund Gosseviewed Foley as having smoothed the ground for the development of theNew Sculpturemovement in British art.[2]

Equestrian works[edit]

Foley received three commissions for large equestrian sculptures of individuals who played prominent roles during the period of British rule in India.

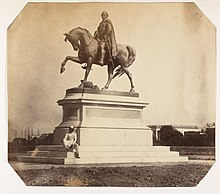

The Art Journalhailed Foley's equestrian statue ofHenry Hardinge, 1st Viscount Hardingeas a "masterpiece of art" and "a triumph of British art".[12][2]William Michael Rossettideclared it to be "markedly at the head of British equestrian statues of any period".[2]Completed in 1857, the statue was the first large equestrian statue not to be conventionally cast but to be created byelectroforming,building up layers of metal for each piece of the statue which were then joined together by electroplating.[12]The statue, which showed Hardinge's horse trampling a broken Sikh artillery piece, was exhibited outside theRoyal Academyin London before it was shipped to Kolkata where it was erected atShaheed Minarnear Government House in 1859.[12][13]The statue was regarded as the most important equestrian statue to be created in Britain during the Victorian era and a bronzed plaster version was displayed at the London International Exhibition of 1862.[3]When in 1962, the Kolkata local authorities began removing British imperial monuments, the statue was returned to Britain.[12]Purchased for £35 by Baroness Helen Hardinge, the statue was erected at her home in Kent before, in 1985, it was relocated to the private garden of another Hardinge descendent near Cambridge.[12]

Foley's equestrian statue ofSir James Outram, 1st Baronetwas regarded as "one of the most magnificent British sculptures in India."[12]Commissioned in 1861, the statue was cast in London from eleven tons of gunmetal seized by the British during theIndian Rebellion of 1857.[3]Foley depicted Outram in a dynamic pose, turning in his saddle to look backwards while pulling up his horse and he considered it his best equestrian work. The statue was unveiled in May 1874 on theMaidanin central Kolkata on a plinth of Cornish granite.[12]For the Calcutta International Exhibition of 1883-84, the entrance to the exhibition was built around the statue.[3]In the 1960s the statue was moved to the grounds of theVictoria Memorial.[12]

By the time he died, Foley had completed an 18-inch tall model ofCharles Canning, 1st Earl Canningon horseback. Both horse and rider were depicted in rigid, motionless poses. All the subsequent work on the commission including the full-size modelling, overseeing of the casting and shipping to India and the design of the plinth were completed by Thomas Brock. The statue was originally unveiled at a central location inBarrackporebut was moved in 1969 to a more remote location, a former British military compound where it was placed on a brick base and sited overlooking the grave of Lady Canning.[12]

Albert Memorial[edit]

In 1864, Foley was chosen to sculpt one of the four large stone groups, each representing a continent, at the corners ofGeorge Gilbert Scott'sAlbert Memorialin Kensington Gardens. His design forAsiawas approved in December of that year. Foley'sAsia,like the other three continental groups, featured a central large animal, in this case an elephant, attended by figures representing different cultures.[2][14]In 1868, Foley was also asked to make the bronze statue of Prince Albert to be placed at the centre of the memorial, following the death ofCarlo Marochetti,who had originally received the commission, but had struggled to produce an acceptable version.[15]By 1870, Foley's full-sized model of Albert was complete and had been accepted. However a series of illnesses slowed Foley's progress and by 1873 only the head of the statue had been cast in bronze while hundreds of other parts were still individual plaster figures. Foley died ofpleurisyin 1874, blamed by some on the extended periods he had spent working surrounded by the wet clay of theAsiamodel.[16] When Foley died, his studentThomas Brocktook over his studio and his first job was to complete the figure of Albert which he did within eighteen months. By then, the Albert Memorial had already been unveiled without the statue of Albert.[16]After the statue of Albert was installed on the monument, it was, briefly, inspected by Queen Victoria in March 1876 before being boarded up for gilding. That original gilding was removed in 1915 but restored in the 2000s.

Foley died at his home "The Priory" inHampstead,north London on 27 August 1874, and was buried in the crypt ofSt. Paul's Cathedralon 4 September.[17][1]He left his models to the Royal Dublin Society, where he had his early artistic education, and a large part of his property to theArtists' Benevolent Fund.[1]SC Hall, the editor ofThe Art Journal,described Foley as being "pensive almost to melancholy.. He was not robust, either in body or in mind; all his sentiments and sensations were graceful: so in truth were his manners. His leisure was consumed by thought."[16]A statue of Foley, on the front of theVictoria and Albert Museum,depicts him as a rather gaunt figure with a moustache, wearing a floppy cap.

Legacy[edit]

As well as the statue of Prince Albert for the Albert Memorial, Thomas Brock completed several more of Foley's commissions. A statue of Queen Victoria for theBirmingham Council Housewas commissioned in 1871 from Foley and completed in 1883 byThomas Woolner.[18]Foley's articled pupil and later studio assistantFrancis John Williamsonalso became a successful sculptor in his own right, reputed to have been Queen Victoria's favourite.[19]Other pupils and assistants wereCharles Bell Birch,Mary GrantandAlbert Bruce Joy.[2]

Following the creation of theIrish Free Statein 1922, a number of Foley's works were removed, or destroyed, as the individuals portrayed were considered hostile to Irish independence. They included those ofLord Carlisle,Lord Dunkellin(inGalway) andField Marshal GoughinPhoenix Park.[20]The statue of Lord Dunkellin was decapitated and dumped in the river as one of the first acts of the short-lived "Galway Soviet" of 1922.[21]

Selected public works[edit]

1839-1849[edit]

| Image | Title / subject | Location and coordinates |

Date | Type | Material | Dimensions | Designation | Wikidata | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Catherine Jane Prendergast (1811-1839) | St. Mary's Church, Chennai | 1839 | Bas-relief | Marble | [12] | |||

|

John Hampden | St Stephen's Hall,Palace of Westminster | 1847 | Statue on pedestal | Marble | [22] | |||

|

William Stokes | Royal College of Physicians of Ireland,Dublin | 1849 | Statue on pedestal | Marble | A former president of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland |

1850-1859[edit]

| Image | Title / subject | Location and coordinates |

Date | Type | Material | Dimensions | Designation | Wikidata | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

More images |

HermaphroditusorA Youth at a Stream | Bancroft Gardens,Stratford-upon-Avon | 1851 | Statue | Bronze | Cast in bronze by J. Hadfield forThe Great Exhibitionof 1851.[23] | |||

| John Selden | St Stephen's Hall,Palace of Westminster | 1853 | Statue on pedestal | Marble | [22] | ||||

More images |

Henry Hardinge, 1st Viscount Hardinge | Shaheed Minar, Kolkata | 1857, erected 1859 | Equestrian statue on pedestal | Bronze | 5.7m statue on 6m pedestal | Grade II listing | Removed from Kolkata and set up on a Hardinge family property atPenshurst,Kent. It was later relocated to the garden of a house inOver, Cambridgeshire.[24][12][25] |

1860-1864[edit]

| Image | Title / subject | Location and coordinates |

Date | Type | Material | Dimensions | Designation | Wikidata | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

More images |

John Nicholson | Lisburn Cathedral | 1862 | Relief | Marble | [26] | |||

| Charles Barry | Palace of Westminster,London | 1863 | Seated statue | [22][2][27] | |||||

| John Elphinstone, 13th Lord Elphinstone | The Asiatic Society of Mumbai | 1864 | Statue on plinth | Marble | [12] | ||||

More images |

Oliver Goldsmith | Trinity College, Dublin | 1864 | Statue on pedestal | Bronze | [2] | |||

More images |

Father Theobald Mathew | St. Patrick's Street,Cork | 1864 | Statue on pedestal | Bronze | Q55027847 | |||

More images |

Charles John, Earl Canning | Westminster Abbey | After 1862 | Statue on pedestal | Marble | [28] | |||

More images |

Asia | Albert Memorial,London | 1864 | Sculpture group | Stone | Grade I listed | Q120199176 | [29][30] | |

| Nusserwanji Maneckji Petit (1827-91) | Gowalia Tank,Mumbai | 1865 | Statue on pedestal | Marble | Pedestal by Paolo Triscornia of Carrara[12] |

1865-1869[edit]

| Image | Title / subject | Location and coordinates |

Date | Type | Material | Dimensions | Designation | Wikidata | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sir Henry Marsh, 1st Baronet | Royal College of Physicians of Ireland,Dublin | 1866 | Statue | Marble | [31] | |||

|

John Sheepshanks | Victoria & Albert Museum | 1866 | Bust | Marble | 78.7cm tall | [32] | ||

More images |

O'Connell Monument | O'Connell Street,Dublin | 1864, unveiled 1882 | Statue on pedestal with supporting figures | Bronze and stone | 11.7m tall | Q33123185 | [2][33] | |

| Albert, Prince Consort | Birmingham Council House | 1866 | Statue on pedestal | Carrara marble | Statue 230cm, pedestal 93cm | [18] | |||

More images |

Colin Campbell, 1st Baron Clyde | George Square,Glasgow | 1867 | Statue on pedestal | Bronze and granite | Category B | Q17792870 | [34] | |

More images |

StatueofSidney Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Lea | Waterloo Place,London | 1867 | Statue on pedestal | Bronze | Grade II | Q25311606 | First unveiled nPall Mall.Moved to theWar Office,Whitehall, in 1906. In 1915 it was moved to Waterloo Place.[35][16][36] | |

More images |

Albert, Prince Consort | Leinster House,Dublin | 1868 | Statue on pedestal with supporting figures | Bronze | ||||

More images |

Edmund Burke | Trinity College Dublin | 1868 | Statue on pedestal | Bronze and stone | ||||

|

John Fielden | Centre Vale Park,Todmorden | Designed 1863, erected 1869 | Statue on pedestal | Bronze and granite | Grade II | [37][30] | ||

|

SirDominic Corrigan | Royal College of Physicians of Ireland,Dublin | 1869 | Statue | Marble | [38] |

1870-1874[edit]

| Image | Title / subject | Location and coordinates |

Date | Type | Material | Dimensions | Designation | Wikidata | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lord Carlisle | Phoenix Park,Dublin | 1870 | Statue on pedestal | Statue removed 1956 | ||||

| Charles Canning, 1st Earl Canning | Barrackpore,India | 1874 | Equestrian statue | Bronze | Completed posthumously from Foley's model byThomas Brock[22][39][12] | ||||

More images |

Sir James Outram, 1st Baronet | Maidan,Kolkata | 1874 | Equestrian statue on pedestal | Bronze and Cornish granite | Q92360193 | Relocated to the gardens of theVictoria Memorial, Kolkata[39][12] | ||

More images |

SirBenjamin Lee Guinness | Grounds ofSt Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin | 1875 | Seated statue on pedestal | Bronze and stone | ||||

More images |

Stonewall Jackson | Capitol Square,Richmond, Virginia | Unveiled 1875 | Statue on pedestal | Bronze and stone | [7][40] | |||

More images |

Albert, Prince Consort | Albert Memorial,London | Installed 1876 | Seated statue | Gilded bronze | 4.2m tall statue | Grade I | Q120199176 | Completed by Thomas Brock[29] |

More images |

Henry Grattan | College Green, Dublin | 1876 | Statue on pedestal | Bronze | Model shown in Dublin in 1872; statue inaugurated January 1876. | |||

More images |

Michael Faraday | Royal Institution,London | 1876 | Statue | Marble | Q120448320 | The statue was completed by Thomas Brock after Foley's death and installed in 1876.[41] | ||

|

Robert James Graves | Royal College of Physicians of Ireland,Dublin | 1877 | Statue | Marble | Completed byAlbert Bruce Joyafter Foley's death[6] | |||

More images |

William Rathbone V | Sefton Park,Liverpool | 1877 | Statue on pedestal with relief panels | Portland stone | Grade II | Q2633129 | Statue by Foley, relief panels by Brock[42] | |

More images |

Hugh Gough, 1st Viscount Gough | Chillingham Castle,Northumberland | 1878 | Equestrian statue on pedestal | Previously inPhoenix Park, Dublin | ||||

More images |

Michael Faraday | Savoy Place, London | 1989 | Statue | Bronze | Q27154696 | Bronze copy of Foley's 1876 marble statue of Faraday in theRoyal Institution.[16] |

Other works[edit]

- Memorial to SirHenry Lawrence,1858, inSt. Paul's Cathedral, Kolkataconsisting of a marble relief portrait in a gothic frame.[12]

- Memorial toWilliam Ritchie,1865, inSt. Paul's Cathedral, Kolkataconsisting of a marble bust portrait supported by two figures representingJusticeandTruth.[12]

- Bust of Major-GeneralWilliam Nairn Forbes,1858, marble version in the formerSilver Mintbuilding on Strand Road, Kolkata and painted plaster model held by the Asiatic Society, Kolkata.[12]

- Egeria(1856) andCaractacus(1857), for the Mansion House, London.Bury Art Museumalso has a version of Egeria.

- The Elder Brother from Comus(1860), Foley's Royal Academy diploma work.

- The Muse of Painting(1866), a monument toJames Ward,R.A. at Kensal Green Cemetery.[22]

- SirJoshua Reynolds,2m tall marble statue,Tate Gallerycollection.[43]

- Marble relief portrait ofWilliam Hookham Carpenter,51.3 cm square, in theBritish Museum.[44][45]

- Ulick de Burgh, Lord Dunkellin(1873), Eyre Square, Galway

- Statue in memory of George Howard[1],the 7th Earl of Carlisle. Moat Hill, Brampton Cumbria 1869 (another version in Dublin was blown up by IRA 1956)

- Memorial to the lawyer James Stuart (1854) forColombo,Sri Lanka

- TheNational Portrait Gallery, Londonholds two portrait busts, both in marble, of the poetBryan Procterand of the actressHelena Faucitby Foley[46]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^abcdefgChisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 599.

- ^abcdefghij"Foley, John Henry".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press. 23 September 2004.doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9786.Retrieved4 October2023.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^abcdeMartina Droth, Jason Edwards & Michael Hatt (2014).Sculpture Victorious: Art in the Age of Invention, 1837-1901.Yale Center for British Art, Yale University Press.ISBN9780300208030.

- ^A.P. Behan (Spring 2001). "Bye Bye Century!".Dublin Historical Record.54(1). Old Dublin Society: 82–100.JSTOR30101842.

- ^John T. Turpin (March 1979). "The Career and Achievement of John Henry Foley, Sculptor (1818-1874)".Dublin Historical Record.32(2): 42–53.JSTOR30104301.

- ^abUniversity of Glasgow History of Art / HATII (2011)."John Henry Foley RA, RHA".Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851–1951.Retrieved30 September2023.

- ^abcdefJames Mackay (1977).The Dictionary of Western Sculptors in Bronze.Antique Collectors' Club.ISBN0902028553.

- ^Algernon Graves (1905).The Royal Academy: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors from its Foundations in 1769 to 1904.Vol. 3. London: Henry Graves. pp. 130–2.

- ^"Ino and Bacchus".Yale Center for British Art.Retrieved29 September2023.

- ^Catalogue of the Sculpture, Paintings, Engravings, and Other Works of Art belonging to the Corporation, together with the Books not included in the Catalogue of the Guildhall Library. Part the First.Printed for the use of the members of the Corporation of London. 1867. pp. 43–7.

- ^Jeremy Cooper (1975).Nineteenth-century Romantic Bronzes, French, English and American Bronzes 1830–1915.David & Charles.ISBN0715363468.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrMary Ann Steggles & Richard Barnes (2011).British Sculpture in India: New Views & Old Memories.Frontier Publishing.ISBN9781872914411.

- ^University of Glasgow History of Art / HATII (2011)."Equestrian statue of Lord Hardinge".Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851–1951.Retrieved4 October2023.

- ^HW Janson (1985).Nineteenth-century Sculpture.Thames & Hudson.

- ^F. H. W. Sheppard (General Editor) (1975)."Albert Memorial: The memorial".Survey of London: volume 38: South Kensington Museums Area.Institute of Historical Research.Retrieved12 October2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^abcdeJohn Blackwood (1989).London's Immortals. The Complete Outdoor Commemorative Statues.Savoy Press.ISBN0951429604.

- ^Sinclair, W.(1909).Memorials of St Paul's Cathedral.Chapman & Hall, Ltd. p. 469.

- ^abGeorge T. Noszlopy (1998).Public Sculpture of Birmingham including Sutton Coldfield.Liverpool University Press / Public Monuments & Sculpture Association.ISBN0-85323-692-5.

- ^"Francis John Williamson (1833-1920)".The Victorian Web.Retrieved29 August2013.

- ^Notes on destruction and removal, accessed 20 January 2009

- ^Citation, accessed 6 July 2009

- ^abcdeTurpin, John T. (1979). "Catalogue of the Sculpture of J.H. Foley".Dublin Historical Record.32:108–18.

- ^Waymark UK Image Gallery

- ^Sworder, John."St Peter's Church".Fordcombe Village. Archived fromthe originalon 10 January 2016.Retrieved24 April2013.

- ^Historic England."Equestrian statue of Viscount Hardinge in the grounds of Albion Villa (Number 6 Church End) (1331332)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved25 September2023.

- ^Potterton, Homan (1975).Irish Church Monuments, 1570-1880.Belfast.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Malcolm Hay & Jacqueline Riding (1996).Art in Parliament - The Permanent Collection of the House of Commons.Jarrod Publishing & The Palace of Westminster.ISBN0-7117-0898-3.

- ^"George, Charles and Stratford Canning".Westminster Abbey.Retrieved23 September2023.

- ^abHistoric England."Prince Consort National Memorial (1217741)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved13 September2023.

- ^abJo Darke (1991).The Monument Guide to England and Wales.Macdonald Illustrated.ISBN0-356-17609-6.

- ^"Memorial statue of Sir Henry Marsh in the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland"(PDF).The Internet Archive.Dublin University Press, 1867.Retrieved2 October2023.

- ^"John Sheepshanks (bust)".Victoria and Albert Museum.Retrieved15 September2023.

- ^Potterton, Homan (1973).The O'Connell Monument.Dublin.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Historic Environment Scotland."George Square, Field Marshall Lord Clyde Statue (Category B Listed Building) (LB32694)".Retrieved13 September2022.

- ^Historic England."Statue of Sydney Herbert (1239318)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved28 September2023.

- ^Philip Ward-Jackson (2011).Public Sculpture of Britain Volume 1: Public Sculpture of Historic Westminster.Liverpool University Press / Public Monuments & Sculpture Association.ISBN978-1-84631-662-3.

- ^Historic England."The Fielden Statue (1314073)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved8 November2021.

- ^Christine Casey (2005).Dublin: the city within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park.New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 483.ISBN9780300109238.

- ^ab"Information on Sculptures".Victoria Memorial Hall. Archived fromthe originalon 27 January 2013.Retrieved25 February2013.

- ^"Monument to Thomas 'Stonewall' Jackson in Capitol Square".Encyclopedia Virginia.Retrieved15 September2023.

- ^Frank AJL James, ed. (2017).'The Common Purposes of Life': Science and Society at the Royal Institution of Great Britain.London: Taylor & Francis. p. 73.ISBN978-1351963176.

- ^Historic England."Statue of William Rathbone (1073451)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved26 September2023.

- ^Emily Fisher (April 2005)."Foley: Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA".Tate.Retrieved29 September2023.

- ^Aileen Dawson (1999).Portrait Sculpture A Catalogue of the British Museum collection c. 1675-1975.British Museum Press.ISBN0714105988.

- ^"Relief, William Hookham Carpenter".British Museum.Retrieved27 September2023.

- ^"John Henry Foley".National Portrait Gallery.Retrieved3 October2023.

External links[edit]

Media related toJohn Henry Foleyat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toJohn Henry Foleyat Wikimedia Commons- 32 artworks by or after John Henry Foleyat theArt UKsite