Johor Bahru

Johor Bahru | |

|---|---|

| City of Johor Bahru Bandaraya Johor Bahru | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| •Jawi | جوهر بهارو |

| • Chinese | Tân sơn(Simplified) Tân sơn(Traditional) Xīnshān(Hanyu Pinyin) |

| •Tamil | ஜொகூர் பாரு Jokūr Pāru(Transliteration) |

From top, left to right: Downtown skyline at night,Johor-Singapore CausewayandJohor Bahru Sentralthe transport hub inSouthern Integrated Gateway,Skyline of the city centre, Forest City (Hutan Bandar) Recreational Park, Danga Bay, theSultan Ibrahim Building,theSultan Abu Bakar Mosque,and theFigure Museum | |

| Nickname(s): JB, Bandaraya Selatan(Southern City) | |

Location of Johor Bahru in Johor | |

| Coordinates:01°27′20″N103°45′40″E/ 1.45556°N 103.76111°E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| District | |

| Administrative areas | List |

| Founded | 10 March 1855 (as Tanjung Puteri) |

| Establishment of the local government | 1933 |

| Establishment of the Town Board | 1950 |

| Municipality status | 1 April 1977 |

| City status | 1 January 1994 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City council |

| • Body | Johor Bahru City Council |

| • Mayor | Noorazam Osman |

| Area | |

| • Total | 391.25 km2(151.06 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 32 m (105 ft) |

| Population (2020)[3] | |

| • Total | 858,118 |

| • Density | 2,192/km2(5,680/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Johor Bahru |

| Time zone | UTC+8(MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+8(Not observed) |

| Postal code | 80xxx to 81xxx |

| Area code(s) | 07 |

| Vehicle registration | J |

| Website | www |

Johor Bahru(Malaysian:[ˈdʒohorˈbahru]), colloquially referred to asJB,is thecore cityofJohor Bahru District,and the capital city of thestateofJohor,Malaysia(the second-largest district in the country, by population).[4]It is the second-largest national GDP-contributor among the major cities in Malaysia,[5]and forms a part ofIskandar Malaysia,the nation's largestspecial economic zone,by investment value.[6]The city has a population of 858,118 people within an area of 391.25 km2.

As the financial centre and logistics hub of southernPeninsular Malaysia,Johor Bahru has been ranked the second-most competitive city in the nation behind the capital,Kuala Lumpur.[7]Geographically, it is located at the southern end of theMalay Peninsula,along the north bank of theStraits of Johor,north of thecity-statemetropolisSingapore. Johor Bahru serves as one of two international border crossings, on the Malaysian side, between the country and Singapore (the other being theSecond LinkatIskandar Puteri), making it thebusiest international border crossing in the world;its direct land link to Singapore, via thecausewayand theRTS Link,is a key economic driver of theborder city.Johor Bahru is categorised as Zone A ofIskandar Malaysia,adjacent toSenai International Airportand the 16th-busiest port in the world,Tanjung Pelepas.

During the reign ofSultanAbu Bakar(between 1886–1895), there was further development and modernisation within the city, with the construction of administrative centres, offices, schools, civic and religious buildings, and railways connecting toWoodlandsinNorth Singapore.Along with most of Southeast Asia,Japanese forcesoccupied Johor Bahru from 1942 to 1945 during thePacific War.Johor Bahru thus became the post-war cradle ofMalay nationalism,and a major political party (known as theUnited Malays National Organisation,or UMNO) was founded at theIstana Besarof Johor Bahru in 1946. After theformation of modern Malaysiain 1963, Johor Bahru retained its status as state capital, and was eventually granted city status, in 1994.

Etymology[edit]

The present area of Johor Bahru was originally known asTanjung Puteri,and was a fishing village of theMalays.TemenggongDaeng Ibrahimthen renamedTanjung PuteritoIskandar Puteriupon his arrival to the area in 1858, after acquiring the territory fromSultan Ali.[8]It was renamed to Johor Bahru bySultan Abu Bakarfollowing the Temenggong's death.[9]The word "Bah(a)ru" means "new" in Malay; thus, Johor Bahru means "New Johor".Bahruis normally written as "baru" in English (Roman) characters, today, although the word appears in other place names with several English spelling variants, such as inKota Bharu,Kelantan, andPekanbaru,Riau(Indonesia). TheBritishpreferred to write it asJohore BahruorJohore Bharu,[10]though the currently-accepted western spelling isJohor Bahru—Johoreis only speltJohor,without the letter "e" at the end of the word, in theMalay language.[11][12]The city's name is also spelt as Johor Baru or Johor Baharu.[13][14]

Johor Bahru was once known asShantou,or "Little Swatow", by the city'sChinese community,as most of the Chinese residents areTeochewwhose ancestry can be traced back toShantou,China; they arrived in the mid-19th century, during the reign of Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim.[15]The city, however, is generally known in Chinese asXinshan,meaning "New Mountain" (Chinese:Tân sơn;pinyin:Xīnshān), as "mountain" may be used to mean "territory" or "land". The name "New Mountain" distinguished it from "Old Mountain" (Jiushan), once used to refer toKranjiandSembawang(in Singapore), where the Chinese first cultivatedblack pepperandgambieron plantations before relocating to new lands in Johor Bahru in 1855.[16][17]

History[edit]

Due to a dispute between the Malays and theBugis,the Johor-Riau Sultanate was split in 1819 with the mainland portion of theJohor Sultanatecoming under the control ofTemenggong Daeng Ibrahimwhile theRiau-Lingga Sultanatecame under the control of the Bugis.[18][19]The Temenggong intended to create a new administration centre for the Johor Sultanate to create a dynasty under the entity of Temenggong.[20]As the Temenggong already had a close relationship with the British and the British intended to have control over trade activities in Singapore, a treaty was signed between SultanAliand Temenggong Ibrahim in Singapore on 10 March 1855.[21]According to the treaty, Ali would be crowned as the Sultan of Johor and receive $5,000 (inSpanish dollars) with an allowance of $500 per month.[22]In return, Ali was required to cede the sovereignty of the territory of Johor (exceptKesangofMuarwhich would be the only territory under his control) to Temenggong Ibrahim.[22]When both sides agreed on Temenggong acquiring the territory, he renamed itIskandar Puteriand began to administer it fromTelok Blangahin Singapore.[9]

As the area was still an undeveloped jungle, Temenggong encouraged the migration ofChineseandJavaneseto clear the land and to develop an agricultural economy in Johor.[23]The Chinese planted the area withblack pepperandgambier,[24]while the Javanese dugparit(canals) to drain water from the land, build roads and plantcoconuts.[25]During this time, a Chinese businessman, pepper and gambier cultivator,Wong Ah Fookarrived; at the same time, theKangchuand Javanese labour contract systems were introduced by the Chinese and Javanese communities.[23][26][27]After Temenggong's death on 31 January 1862, the town was renamed "Johor Bahru" and his position was succeeded by his son, Abu Bakar, with the administration centre in Telok Blangah being moved to the area in 1889.[9]

British administration[edit]

In the first phase of Abu Bakar's administration, the British only recognised him as amaharajarather than asultan.In 1855, theBritish Colonial Officebegan to recognise his status as a Sultan after he metQueen Victoria.[28]He managed to regainKesangterritory for Johor aftera civil warwith the aid of British forces and he boosted the town's infrastructure and agricultural economy.[28][29]Infrastructure such as theState MosqueandRoyal Palacewas built with the aid of Wong Ah Fook, who had become a close patron for the Sultan since his migration during the Temenggong reign.[30]As the Johor-British relationship improved, Abu Bakar also set up his administration under a British style and implemented a constitution known asUndang-undang Tubuh Negeri Johor(Johor State Constitution).[28]Although the British had long been advisers for the Sultanate of Johor, the Sultanate never came under direct colonial rule of the British.[31]The direct colonial rule only came into effect when the status of the adviser was elevated to a status similar to that of aResidentin theFederated Malay States(FMS) during the reign ofSultan Ibrahimin 1914.[32]

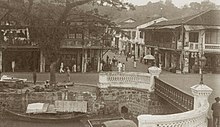

In Johor Bahru, theMalay Peninsula railway extensionwas finished in 1909,[33]and in 1923 the Johor–Singapore Causeway was completed.[34]Johor Bahru developed at a modest ratebetween the First and Second World Wars.The secretariat building—Sultan Ibrahim Building—was completed in 1940 as the British colonial government attempted to streamline the state's administration.[35]

World War II[edit]

The continuous development of Johor Bahru was, however, halted whenthe Japaneseunder GeneralTomoyuki Yamashitainvaded the town on 31 January 1942. As the Japanese had reached northwest Johor by 15 January, they easily captured major towns of Johor such ofBatu Pahat,Yong Peng,KluangandAyer Hitam.[36]The British and otherAllied forceswere forced to retreat towards Johor Bahru; however, following a further series of bombings by the Japanese on 29 January, the British retreated to Singapore and blew up the causeway the following day as a final attempt to stop the Japanese advance in British Malaya.[36]The Japanese then used the Sultan's residence ofBukit Serene Palacelocated in the town as their main temporary base for their future initial plans toconquer Singaporewhile waiting to reconnect the causeway.[37][38]The Japanese chose the palace as their main base because they already knew the British would not dare to attack it as this would harm their close relationship with Johor.[36]

In less than a month, the Japanese repaired the causeway and invaded the Singapore island easily.[39]Soon after the war ended in 1946, the town became the main hotspot forMalay nationalismin Malaya.Onn Jaafar,a local Malay politician who later became theChief Minister of Johor,formed theUnited Malay National Organisationparty on 11 May 1946 when the Malays expressed their widespread disenchantment over theBritish government's action for granting citizenship laws to non-Malays in the proposed states of theMalayan Union.[40][41]An agreement over the policy was then reached in the town with Malays agreeing with the dominance of economy by the non-Malays and the Malays' dominance in political matters being agreed upon by non-Malays.[42]Racial conflict between the Malay and non-Malays, especially the Chinese, is being provoked continuously since theMalayan Emergency.[43]

Post-independence[edit]

After the formation of the Federation of Malaysia in 1963,[44]Johor Bahru continued as the state capital and more development was carried out, with the town's expansion and the construction of more new townships and industrial estates. TheIndonesian confrontationdid not directly affect Johor Bahru as the main Indonesian landing point in Johor was inLabisandTenanginSegamat Districtas wellPontian District.[45][46]There was only one active Indonesian spy organisation in the town, known asGerakan Ekonomi Melayu Indonesia(GEMI). They frequently engaged with the Indonesian communities living there to contribute information for Indonesian commandos until thebombing of the MacDonald Housein Singapore in 1965.[47][note 1]By the early 1990s, the town had considerably expanded in size, and was officially granted acity statuson 1 January 1994.[48]Johor Bahru City Councilwas formed and the city's current main square,Dataran Bandaraya Johor Bahru,was constructed to commemorate the event. A central business district was developed in the centre of the city from the mid-1990s in the area aroundWong Ah Fook Street.The state and federal government channelled considerable funds for the development of the city—particularly more so after 2006, when theIskandar Malaysiawas formed.[49][50]However, more than ten years of unbridled building construction in Iskandar, especially of higher-end high-rise apartments and commercial property, has led to a serious glut of such property in the region. Occupancy of high-rise accommodation has been predicted to fall to 50 percent, and commercial property to 65 percent, by the end of 2019 due to continued incoming supply.[51]

Governance[edit]

As the capital city of Johor, the city plays an important role in the economic welfare of the entire state's population. There is one member of parliament (MP) representing the singleparliamentary constituency(P.160) in the city. The city also elects two representatives to the state legislature from the state assembly districts of Larkin and Stulang.[52]

Local authority and city definition[edit]

The city is administered by theJohor Bahru City Council.The current mayor is Dato' Haji Mohd Noorazam bin Dato' Haji Osman, which took office since 15 August 2021.[53][54]Johor Bahruobtained city statuson 1 January 1994.[48]The area under the jurisdiction of the Johor Bahru City Council includes Central District, Kangkar Tebrau,Kempas,Taman Sri Bahagia, Danga Bay, Taman Suria, Kampung Majidee Baru, Southkey, Taman Sri Tebrau, Taman Abad, Taman Sentosa, Banda Baru Uda, Taman Perling,Larkin,Majidee, Kampung Maju Jaya, Bandar Dato´ Onn, Seri Austin, Adda Heights, Taman Gaya, Taman Daya, Taman Bukit Aliff, Setia Tropika, Taman Johor, Taman Anggerik, Taman Sri Putra, Mount Austin, Pandan,Pasir Pelangi,Pelangi, Taman Johor Jaya, Taman Molek,Permas Jaya,Rinting,Tampoi,Tasek Utara andTebrau.[55]This covers an area of 220 square kilometres (85 sq mi).[1]Currently there are 11 council members in the city council, which consists of 3Amanahmembers, 3Bersatumembers, 3DAPmembers and 2PKRmembers.[56]In August 2021, mayor Adib Azhari Daud was arrested and taken into custody for allegedly accepting bribes from contractors while overseeing development of Johor Bahru. The arrest marks the first time an active Johor mayor has been arrested.[57]

Courts of law and legal enforcement[edit]

Thecity high courtcomplex is located along Dato' Onn Road.[58]The Sessions and Magistrate Courts is located on Ayer Molek Road,[58]while anothercourtforSharialaw is located on Abu Bakar Road.[59]The Johor (state) Police Contingent Headquarters is located on Tebrau Road.[60]Johor Bahru's Southern District police headquarters, which also operates as a police station, is on Meldrum Road in the city centre. The Johor Bahru Southern District traffic police headquarters is a separate entity along Tebrau Road, close to the city centre. Johor Bahru's Northern District police headquarters and Northern District Traffic Police headquarters are co-located in Skudai, about 20 km north of the city centre. There are around eleven police stations and seven police substations (Pondok Polis) in the greater Johor Bahru area.[61][62]Johor Bahru Prisonwas located in the city along Ayer Molek Road, but was closed down after 122 years operation in December 2005,[63][64]its function being transferred to an expanded prison in the town of Kluang about 110 km from Johor Bahru.[63]Other temporary lock-ups or prison cells are available in most police stations in the city, as in other parts of Malaysia.[65]

Geography[edit]

Johor Bahru is located along theStraits of Johorat the southern end ofPeninsular Malaysia.[66]Originally, the city area was only 12.12 km2(4.68 sq mi) in 1933 before it was expanded to over 220 km2(85 sq mi) in 2000.[1]

Climate[edit]

The city has an equatorial climate with consistent temperatures, a considerable amount of rain, and high humidity throughout the course of the year. An equatorial climate is atropical rainforest climatemore subject to theIntertropical Convergence Zonethan thetrade windsand with nocyclone.Daily average temperatures range from 26.4 °C (79.5 °F) in January to 27.8 °C (82.0 °F) in April with an average annual rainfall of around 2,350 mm (93 in).[67]The wettest months, with 19 to 25 percent more rain than average, are April, November and December.[68]Although the climate is relatively uniform, it does show some seasonal variation due to the effects ofmonsoons,with noticeable changes in wind speed and direction, cloud cover and amount of rainfall. There are two monsoon periods each year, the first one between mid-October and January, which is the north-east Monsoon. This period is characterised by heavier rainfall and wind from the north-east. The second one is the south-west Monsoon, which hardly affects the rainfall in Johor Bahru, where winds are from the south and south-west. This occurs between June and September.[69]

| Climate data for Johor Bahru (Senai International Airport,2016–2023) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.6 (88.9) |

32.3 (90.1) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

32.3 (90.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 162.6 (6.40) |

139.8 (5.50) |

203.4 (8.01) |

232.8 (9.17) |

215.3 (8.48) |

148.1 (5.83) |

177.0 (6.97) |

185.9 (7.32) |

190.8 (7.51) |

217.7 (8.57) |

237.6 (9.35) |

244.5 (9.63) |

2,355.5 (92.74) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 11 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 162 |

| Source 1: Meteomanz[70] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2:World Meteorological Organisation(precipitation 1974–2000)[68] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

Johor Bahru has an officialdemonymwhere people are commonly referred to as "Johor Bahruans". Theterms"J.B-ites" and "J.B-ians" have also been used to a limited extent. People from Johor are called Johoreans.[71]

Ethnicity and religion[edit]

TheMalaysian Census in 2010reported the population of Johor Bahru as 497,067.[3]The city's population today is a mixture of three main ethnicities – Malays,ChineseandIndians- along with otherbumiputras.Malays comprise a plurality of the population at 240,323, followed by Chinese totalling 172,609, Indians totaling 73,319 and others totalling 2,957.[3]Non-Malaysian citizens form a population of 2,585.[3]The Malays in Johor Bahru are strongly related to the neighbouring Riau Malays inRiau Islands,Indonesiawith significant populations ofJavanese,BugisandBanjareseamong the local Johorean Malay population.[72][73]The Chinese mainly are from the majorityTeochew,Hokkien,HainaneseandHakkadialect groups (with a minority ofCantonese,HenghuaandFoochoweseamong the local Chinese),[15]while the Indian community mainly and predominantly areTamils,there are also small populations ofTelugus,MalayalisandSikhPunjabis.The Malays are majorityMuslims,while the Chinese are predominantlyBuddhists/Taoistsand the Indians were mostlyHindusdespite there is also a small numbers from the two ethnic groups that are Christians and Muslims. A small number ofSikhs,Animistsandsecularistscan also be found in the city.

The following is based on Department of Statistics Malaysia 2010 census.[3]

| Ethnic groups in Johor Bahru, 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Population | Percentage |

| Malay | 240,323 | 48.35% |

| OtherBumiputras | 5,374 | 1.98% |

| Chinese | 172,609 | 34.73% |

| Indian | 73,319 | 13.70% |

| Others | 2,957 | 0.59% |

| Non-Malaysian | 2,585 | 1.57% |

| Total | 497,067 | 100.00% |

Languages[edit]

The local ethnic Malays speak the Malay language,[72]while the language primarily spoken by the local Chinese isMandarin Chinese.The Chinese community is represented by several dialect groups:HokkienandTeochew.[36][74]

The Indian community predominantly speaksTamil,with a minority ofMalayalam,TeluguandPunjabispeakers. The English language (orManglish) is also used considerably,[citation needed]albeit more so among the older generation, who have attended school during the British rule.[75]

Economy[edit]

Johor Bahru is one of the fastest-growing cities in Malaysia afterKuala Lumpur.[76]It is the main commercial centre for Johor and is located in theIndonesia–Malaysia–Singapore Growth Triangle.Tertiary-based industrydominates the economy with many international tourists from the regions visiting the city.[76][77][78]It is the centre of financial services, commerce and retail, arts and culture, hospitality, urban tourism, plastic manufacturing, electrical and electronics and food processing.[79]The main shopping districts are located within the city, with a number of large shopping malls located in the suburbs. Johor Bahru is the location of numerousconferences,congress and trade fairs, such as theEastern Regional Organisation for Planning and Housingand theWorld Islamic Economic Forum.[80][81]The city is the first in Malaysia to practise alow-carbon economy.[82]

The city has a very close economic relationship with Singapore. There are around 3,000 logistic lorries crossing between Johor Bahru and Singapore every day for delivering goods between the two sides for trading activities.[83]Many residents in Singapore frequently visit the city during the weekends; some of them have also chosen to live in the city.[76][77][78][84][85]Many of the city's residents work in Singapore.[86][87]

Transportation[edit]

Land[edit]

The internal roads linking different parts of the city are mostlyfederal roadsconstructed and maintained byMalaysian Public Works Department.There are five major highways linking theJohor Bahru Central Business Districtto outlying suburbs:Tebrau HighwayandJohor Bahru Eastern Dispersal Link Expresswayin the northeast,Skudai Highwayin the northwest,Iskandar Coastal Highwayin the west andJohor Bahru East Coast Highwayin the east.[79]Pasir Gudang Highwayand the connecting Johor Bahru Parkway cross Tebrau Highway and Skudai Highway, which serve as the middlering roadof the metropolitan area. TheJohor Bahru Inner Ring Road,which connects with theSultan Iskandar customs complex,aids in controlling the traffic in and around the central business district.[79]Access to the national expressway is provided through theNorth–South ExpresswayandSenai–Desaru Expressway.[88]TheJohor–Singapore Causewaylinks the city toWoodlands, Singaporewith a six-lane road and a railway line terminating at the Southern Integrated Gateway.[79]

Bus[edit]

The main bus terminal of the city is theLarkin Sentrallocated inLarkin.[89]Other bus terminals include Taman Johor Jaya Bus Terminal[90]and Ulu Tiram Bus Terminal.[91]Larkin Sentral has direct bus services to and from many destinations in West Malaysia, southernThailandand Singapore, while Taman Johor Jaya and Ulu Tiram Bus Terminals serve local destinations.[89]Major bus operators in the city areCauseway Link,Maju and S&S. It is possible to get around the city by bus, though the frequency of the bus might be an issue.

Taxi[edit]

Two types of taxis operate in the city; the main taxi is either in red and yellow, blue, green or red while the larger, less common type is known as alimousinetaxi, which is more comfortable but expensive. Most taxis in the city do not use theirmeter.[92]

Railway[edit]

The city is served by two railway stations, which areJohor Bahru Sentral railway station[93]andKempas Baru railway station.Both stations serve train services to Kuala Lumpur and Singapore.[citation needed]In 2015, a newshuttle trainservice operated byKeretapi Tanah Melayu(KTM) was launched providing transport to Woodlands in Singapore.[94]

Air[edit]

The city is served bySenai International Airportlocated at the neighbouringSenaitown and connected throughSkudai Highway.[95]Four airlines,AirAsia(and its subsidiariesIndonesia AirAsiaandThai AirAsia),Firefly,Malaysia Airlines,Batik Air Malaysiaand formerlyXpress Air,provide flights domestically as well as international flights toJakarta Soekarno–Hatta,Surabaya,Hồ Chí Minh City,andBangkok Don Mueang.[96][97]The nearest major airport isChangi Airportin Singapore located 36.3 km from the city centre.

Sea[edit]

Boat services are available to ports inBatamandBintanIslands inIndonesiafromStulang Laut Ferry Terminal,located near the suburb ofStulang.[95][98]

Other utilities[edit]

Healthcare[edit]

There are threepublic hospitals,[99]fourhealth clinics[100]and thirteen1Malaysia clinicsin Johor Bahru.[101]Sultanah Aminah Hospital,which is located along Persiaran Road, is the largest public hospital in Johor Bahru as well as in Johor with 989 beds.[100]Another government funded hospital is theSultan Ismail Specialist Hospitalwith 700 beds.[100]Another large private health facility is theKPJPuteri Specialist Hospital with 158 beds.[102]Further healthcare facilities are currently being expanded to improve healthcare services in the city.[103]

Education[edit]

Many government or state schools are available in the city. Thesecondary schoolsincludeEnglish College Johore Bahru,Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Engku Aminah, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Sultan Ismail, Sekolah Menengah Infant Jesus Convent, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan (Perempuan) Sultan Ibrahim and Sekolah Menengah Saint Joseph.[104]There are also a number of international schools in the city. These includeMarlborough College Malaysia,Shattuck-St. Mary’s Forest City International School, Raffles American School, Sunway International School. The other private universities are Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia, University of Reading Malaysia, University of Southampton Malaysia. There are also a number of private college campuses and one polytechnic operating in the city; these areCrescendo International College,KPJ College, Olympia College,Sunway College Johor Bahru,Taylor's Collegeand College of Islamic Studies Johor.[105]

Libraries[edit]

The Johor State Library, also known as the Johor Public Library Corporation headquarters is the main library in the state, located off Yahya Awal Road.[106]Another public library branch is the University Park in Kebudayaan Road, while there are other libraries or private libraries in schools, colleges, and universities.[107]Two village libraries are available in the district of Johor Bahru.[108]

Culture and leisure[edit]

Attractions and recreation spots[edit]

Cultural attractions[edit]

There are a number of cultural attractions in Johor Bahru. The Royal Abu Bakar Museum located within theGrand Palacebuilding is the main museum in the city. The Johor Bahru Kwong Siew Heritage located in Wong Ah Fook Street housed the former Cantonese clan house that was donated byWong Ah Fook.[109]TheFoon Yew High Schoolhouses many historical documents of the city history with aChinese culturalheritage.[110][111][112]TheJohor Bahru Chinese Heritage Museumon Ibrahim Road includes the history of Chinese migration to Johor along with a collection of documents, photos, and other artefacts.[113][114]

TheJohor Art Galleryin Petrie Road is a house gallery built in 1910, known as the house for the former third Chief Minister of Johor, Abdullah Jaafar. The house features old architecture and became the centre for the collection of artefacts related to Johor's cultural history since its renovation in 2000.[112]

Historical attractions[edit]

The Grand Palace is one of the historical attractions in the city, and is an example ofVictorian-style architecturewith a garden.Figure Museumis another historical colonial building since 1886 which ever become the house for the Johor first Menteri BesarJaafar Muhammad;it is located on the top of Smile Hill (Bukit Senyum).[115]The English College (nowMaktab Sultan Abu Bakar) established in 1914 was located close to the Sungai Chat Palace before being moved to its present location at Sungai Chat Road; some of the ruins are visible at the old site.[29]TheSultan Ibrahim Buildingis another historical building in the city; built in 1936 by British architectPalmer and Turner,it was the centre of the administration of Johor as since the relocation from Telok Blangah in Singapore, the Johor government never had its own building.[112][116]Before the current railway station was built, there wasJohor Bahru railway station(formerly Wooden Railway) which has now been turned into a museum after serving for 100 years since the British colonial era.[114]

Sultan Abu Bakar State Mosque, located along Skudai Road, is the main and the oldest mosque in the state. It was built with a combination ofVictorian,MoorishandMalayarchitectures.[112][117]TheJohor Bahru Old Chinese Temple,located on the Trus Road, dedicated to the Five Patron Deities from the five Southern Chinese Clans (Hokkien,Teochew,Hakka,Cantonese&Hainanese) in the city. It was built in 1875 and renovated by thePersekutuan Tiong Hua Johor Bahru(Johor Bahru Tiong Hua Association) in 1994–95 with the addition of a small L-shaped museum in one corner of the square premises.[24]The Wong Ah Fook Mansion, the home of the late Wong Ah Fook, was a former historical attraction. It stood for more than 150 years but was demolished illegally by its owner in 2014 to make way for a commercial housing development without informing the state government.[118][119]Other historical religious buildings include theArulmigu Sri Rajakaliamman Hindu Temple,Sri Raja Mariamman Hindu Temple, Gurdwara Sahib andChurch of the Immaculate Conception.[114][115]

Leisure and conservation areas[edit]

TheDanga Bayis a 25 kilometres (16 mi) area of recreational waterfront. There are around 15 established golf courses, of which two offer 36-hole facilities; most of these are located within resorts. The city also features severalpaintballparks which are also used foroff-road motorsportsactivities.[114]

TheJohor Zoois one of the oldest zoos in Malaysia; built in 1928 covering 4 hectares (9.9 acres) of land, it was originally called "animal garden" before being handed to the state government for renovation in 1962.[120]The zoo has around 100 species of animals, includingwild cats,camels,chimpanzees,gorillas,orangutans,and tropical birds.[121]Visitors can participate in activities such as horse riding or usingpedalos.[112]The largest park in the city isIndependence Park.[122]

Other attractions[edit]

Dataran Bandarayawas built after Johor Bahru was proclaimed as a city. The site features aclock tower,fountain and a large field.[112]TheWong Ah Fook Streetis named after Wong Ah Fook. The Tan Hiok Nee Street is named afterTan Hiok Nee,who was the leader of the formerNgee Heng Kongsi,asecret societyin Johor Bahru. Together with the Dhoby Street, both are part of a trail known as Old Buildings Road; they feature a mixture of Chinese and Indian heritages, reflected by their forms of ethnic business and architecture.[114][115]

Shopping[edit]

The Mawar Handicrafts Centre, a government-funded exhibition and sales centre, is located along the Sungai Chat road and sells various batik andsongketclothes.[39]Opposite this is the Johor Area Rehabilitation Organisation (JARO) Handicrafts Centre which sells items such as hand-made cane furniture, soft toys andrattanbaskets made by thephysically disabled.[114][123]

Entertainment[edit]

The oldest cinema in the city is the Broadway Theatre which mostly screensTamilandHindimovies. There are around other five cinemas available in the city with all of them located inside shopping malls.[114]

Sports[edit]

The city's main association football club is aJohor Darul Ta'zim F.C.Its home stadium isSultan Ibrahim Stadiumhas a capacity of around 40,000. There is also afutsalcentre, known as Sports Prima, which has eight minimum-sizedFIFAapproved futsal courts; it is the largest indoor sports centre in the city.[124]

Radio stations[edit]

Two radio stations have their offices in the city:Best FM(104.1)[125]andJohor FM(101.9).[126]

Crime[edit]

Johor Bahru was once notorious for its relatively high crime rate, compared to other urban areas in Malaysia. In 2014, Johor Bahru South police district recorded one of the highest crime rates in the country with 4,151 cases, behindPetaling Jaya.[127]In 2013, the city also accounted for 70% of crimes committed in the entire state ofJohor,with a Johor police spokesman admitting that Johor Bahru remained a crime hotspot within the state.[128]Crime in Johor Bahru has also received substantial media coverage by the Singaporean press, as Singaporeans visiting or transiting through the neighbouring city are often targeted by criminals.[128][129][130]

Among the more common criminal cases in Johor Bahru are robberies, snatch theft,carjacking,kidnapping and rape.[128][131][132]Gang and unarmed robberies accounted for about 76% of the city's criminal cases in 2013 alone.[131]Illegal car cloning is also rampant in the city.[133]In addition, Johor Bahru's reputation forsleazestill exists, with some areas in the city centre turning intored-light districts,despiteprostitution being illegal in Malaysia.[134][135]

International relations[edit]

Several countries have set up their consulates in Johor Bahru, including Indonesia[136]and Singapore, while Japan has closed its consular office since 2014.[137]

Twin towns – Sister cities[edit]

Johor Bahru'ssister citiesare:

Changzhou, Jiangsu,China[138]

Changzhou, Jiangsu,China[138] Kuching, Sarawak,Malaysia[139]

Kuching, Sarawak,Malaysia[139] Istanbul,Türkiye (Turkey)[140][141]

Istanbul,Türkiye (Turkey)[140][141]

In popular culture[edit]

Movies[edit]

- Punggok Rindukan Bulan(2008)

Notable people[edit]

- Christina Jordan(born 1962), Malaysian-born British politician[142]

- Vivien Yeo(born 1984), Malaysian actress based in Hong Kong

- Gin Lee(born 1987), Malaysian singer based in Hong Kong

- Robert Kuok(born 1923), Business magnate, investor, and philanthropist. Top 100 wealthiest people in world.

- Ng Tze Yong(born 2000), national badminton player[143]

- Ronny Chieng(born 1985), Malaysian comedian and actor based in United States

- Tunku Abdul Rahman Hassanal Jeffri(born 1993), racing driver and member of theJohor Royal Family

- Sebastian Francis,(born 1959), fifth bishop ofRoman Catholic Diocese of Penangandcardinalof the Catholic Church

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Another early attack to destabilise Malaysia was done with the murder of Malaytrishawin Singapore that led to the racial conflict between Malay and Chinese there. At the first stage of the conflict, it was alleged the murder was done by a Chinese but this was however turned down when further investigation revealed the murder was actually done by Indonesian agents who had infiltrate Singapore in an attempt to weakening the unity of race there duringthe state was still part of Malaysia.(Drysdale, Halim and Jamie)

References[edit]

- ^abc"Background (Total Area)".Johor Bahru City Council.Archived fromthe originalon 22 August 2015.Retrieved22 August2015.

- ^"Malaysia Elevation Map (Elevation of Johor Bahru)".Flood Map: Water Level Elevation Map. Archived fromthe originalon 22 August 2015.Retrieved22 August2015.

- ^abcde"Total population by ethnic group, Local Authority area and state, Malaysia"(PDF).Statistics Department, Malaysia. 2010. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 14 November 2013.Retrieved12 March2012.

- ^"DOSM: Petaling district has highest population, density in 2023".thesundaily.my.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^"Achieving A System of Competitive Cities in Malaysia: Main Report"(PDF).World Bank Group & Khazanah Nasional.November 2015.

- ^Lee, Shaun (14 January 2019)."An international metropolis 13 years in the making".DHL Logistics of Things.Retrieved27 October2023.

- ^Ni Pengfei, Marco Kamiya, Guo Jing, Zhang Yi, etc."Global Urban Competitiveness Report (2020–2021)"(PDF).United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Zainol Abidin Idid (Syed.).Pemeliharaan warisan rupa bandar: panduan mengenali warisan rupa bandar berasaskan inventori bangunan warisan Malaysia(in Malay). Badan Warisan Malaysia.ISBN978-983-99554-1-5.

- ^abc"Background of Johor Bahru City Council and History of Johor Bahru"(PDF).Malaysian Digital Repository. 12 March 2013. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 June 2015.Retrieved27 June2015.

- ^Margaret W. Young; Susan L. Stetler; United States. Department of State (October 1985).Cities of the world: a compilation of current information on cultural, geograph. and polit. conditions in the countries and cities of 6 continents, based on the Dep. of State's "Post Reports".Gale.ISBN978-0-8103-2059-8.

- ^Gordon D. Feir (10 September 2014).Translating the Devil: Captain Llewellyn C Fletcher Canadian Army Intelligence Corps In Post War Malaysia and Singapore.Lulu Publishing Services. pp. 378–.ISBN978-1-4834-1507-9.[permanent dead link]

- ^Cheah Boon Kheng (1 January 2012).Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941–1946.NUS Press. pp. 13–.ISBN978-9971-69-508-8.

- ^Carl Parkes (1994).Southeast Asia Handbook.Moon Publications.ISBN9781566910026.

- ^Library of Congress (2009).Library of Congress Subject Headings.Library of Congress. pp. 4017–.

- ^ab"Keeping the art of Teochew opera alive".New Straits Times.AsiaOne.24 July 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 24 July 2015.Retrieved24 July2015.

- ^Heng, Jason (2021).Decoding Sejarah Melayu: The Hidden History of Ancient Singapore.Jason Heng.ISBN9798201638450.

- ^Patricia Pui Huen Lim (2002).Wong Ah Fook: Immigrant, Builder, and Entrepreneur.Times Editions. p. 35.ISBN9789812323699.

- ^Donald B. Freeman (17 April 2003).Straits of Malacca: Gateway or Gauntlet?.McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. pp. 157–.ISBN978-0-7735-7087-0.

- ^Kanji Nishio (2007).Bangsa and Politics: Melayu-Bugis Relations in Johor-Riau and Riau-Lingga.

- ^M. A. Fawzi Mohd. Basri (1988).Johor, 1855–1917: pentadbiran dan perkembangannya(in Malay). Fajar Bakti.ISBN978-967-933-717-4.

- ^"Johor Treaty is signed".National Library Board. 10 March 1855. Archived fromthe originalon 30 June 2015.Retrieved30 June2015.

- ^abAbdul Ghani Hamid (3 October 1988)."Tengku Ali serah Johor kepada Temenggung (Kenangan Sejarah)"(in Malay).Berita Harian.Retrieved30 June2015.

- ^abc"History of the Johor Sultanate".Coronation of HRH Sultan Ibrahim. 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 2 July 2015.Retrieved2 July2015.

- ^abS. Muthiah (19 June 2015)."The city that gambier built".The Hindu.Archived fromthe originalon 19 August 2015.Retrieved19 August2015.

- ^Carl A. Trocki (2007).Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784–1885.NUS Press. pp. 152–.ISBN978-9971-69-376-3.

- ^Patricia Pui Huen Lim (1 July 2000).Oral History in Southeast Asia: Theory and Method.Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 119–.ISBN978-981-230-027-0.

- ^Patricia (2002), p. 129–132

- ^abcMuzaffar Husain Syed; Syed Saud Akhtar; B D Usmani (14 September 2011).Concise History of Islam.Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. pp. 316–.ISBN978-93-82573-47-0.

- ^abDominique Grele (1 January 2004).100 Resorts Malaysia: Places with a Heart.Asiatype, Inc. pp. 292–.ISBN978-971-0321-03-2.

- ^Cheah Jin Seng (15 March 2008).Malaya: 500 Early Postcards.Didier Millet Pte, Editions.ISBN978-981-4155-98-4.

- ^Fr Durand; Richard Curtis (28 February 2014).Maps of Malaysia and Borneo: Discovery, Statehood and Progress.Editions Didier Millet. pp. 177–.ISBN978-967-10617-3-2.

- ^"Johor is brought under British control".National Library Board. 12 May 1914. Archived fromthe originalon 30 June 2015.Retrieved30 June2015.

- ^Winstedt (1992), p. 141

- ^Winstedt (1992), p. 143

- ^Oakley (2009), p. 181

- ^abcdPatricia Pui Huen Lim; Diana Wong (1 January 2000).War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore.Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 140–145.ISBN978-981-230-037-9.

- ^Richard Reid."War for the Empire: Malaya and Singapore, Dec 1941 to Feb 1942".Australian War Memorial.Australia-Japan Research Project. Archived fromthe originalon 2 July 2015.Retrieved2 July2015.

- ^Bill Yenne (20 September 2014).The Imperial Japanese Army: The Invincible Years 1941–42.Osprey Publishing. pp. 140–.ISBN978-1-78200-982-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^abWendy Moore (1998).West Malaysia and Singapore.Tuttle Publishing. pp. 186–187.ISBN978-962-593-179-1.

- ^Swan Sik Ko (1990).Nationality and International Law in Asian Perspective.Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 314–.ISBN978-0-7923-0876-8.

- ^Keat Gin Ooi (1 January 2004).Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor.ABC-CLIO. pp. 1365–.ISBN978-1-57607-770-2.

- ^Christoph Marcinkowski; Constance Chevallier-Govers; Ruhanas Harun (2011).Malaysia and the European Union: Perspectives for the Twenty-first Century.LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 159–.ISBN978-3-643-80085-5.

- ^M. Stenson (1 November 2011).Class, Race, and Colonialism in West Malaysia.UBC Press. pp. 89–.ISBN978-0-7748-4440-6.

- ^Arthur Cotterell (15 July 2014).A History of South East Asia.Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 341–.ISBN978-981-4634-70-0.

- ^K. Vara (16 February 1989)."Quiet town with a troubled past".New Straits Times.Retrieved5 July2015.

- ^"Indonesian Confrontation, 1963–66".Australian War Memorial. Archived fromthe originalon 4 July 2018.Retrieved4 July2018.

- ^Mohamed Effendy Abdul Hamid; Kartini Saparudin (2014)."MacDonald House bomb explosion".National Library Board. Archived fromthe originalon 5 July 2015.Retrieved5 July2015.

- ^ab"Background"(in English and Malay). Johor Bahru City Council. Archived fromthe originalon 4 July 2015.Retrieved4 July2015.

- ^Zaini Ujang (2009).The Elevation of Higher Learning.ITBM. pp. 46–.ISBN978-983-068-464-2.

- ^Oxford Business Group Malaysia (2010).The Report: Malaysia 2010 – Oxford Business Group.Oxford Business Group. pp. 69–.ISBN978-1-907065-20-0.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^Rachel Chew (16 January 2019)."JB's high-rise residences vacancy rate expected to hit an unprecedented above 50% this year".edgeprop.my.Retrieved19 February2019.

- ^"List of Parliamentary Elections Parts and State Legislative Assemblies on Every States".Ministry of Information Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 18 May 2014.Retrieved7 July2015.

- ^"Sesi 'Clock In' Datuk Bandar MBJB Ke 11 Tuan Haji Amran bin A.Rahman".Johor Bahru City Council(in Malay). 23 July 2018.Retrieved23 July2018.

- ^"Mayor's Profile".Johor Bahru City Council. Archived fromthe originalon 3 September 2015.Retrieved3 September2015.

- ^"Administrative areas of Johor Bahru City Council".Johor Bahru City Council. Archived fromthe originalon 27 July 2015.Retrieved27 July2015.

- ^"MBJB laksana kaedah pentadbiran baharu"(in Malay). Sinar Online. 17 July 2018.Retrieved23 July2018.

- ^"Johor Baru mayor arrested over alleged kickbacks from building projects,"The Straits Times, 11 August 2021, retrieved 26 August 2021

- ^ab"Senarai Mahkamah Johor"(in Malay). Johor Law Courts Official Website. Archived fromthe originalon 1 August 2015.Retrieved1 August2015.

- ^"Johore Syariah Court Directory".E-Syariah Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 1 August 2015.Retrieved1 August2015.

- ^"Johor Police Contingent".Johor Police Contingent. Archived fromthe originalon 1 August 2015.Retrieved1 August2015.

- ^"Direktori PDRM Johor – Johor Bahru (Utara)"(in Malay).Royal Malaysia Police.Archived fromthe originalon 8 April 2016.Retrieved1 August2015.

- ^"Direktori PDRM Johor – Johor Bahru (Selatan)"(in Malay). Royal Malaysia Police. Archived fromthe originalon 9 April 2016.Retrieved1 August2015.

- ^ab"Penjara Johor Bahru Dalam Kenangan"(in Malay).Prison Department of Malaysia.12 December 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 1 August 2015.Retrieved1 August2015.

- ^"Prison Address & Directory".Prison Department of Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 1 August 2015.Retrieved1 August2015.

- ^"Soalan Lazim (Frequently Asked Questions)"(in Malay). Prison Department of Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 28 March 2016.Retrieved28 March2016.

- ^Eric Wolanski (18 January 2006).The Environment in Asia Pacific Harbours.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 349–.ISBN978-1-4020-3654-5.

- ^"Weather Data For Johor Bahru".Weatherbase.25 February 2019.Retrieved25 February2019.

- ^ab"World Weather Information Service – Johor Bahru".World Meteorological Organisation. Archived fromthe originalon 23 October 2013.Retrieved25 March2015.

- ^"Malaysia".Climates To Travel.25 February 2019.Retrieved25 February2019.

- ^"SYNOP/BUFR observations. Data by months".Meteomanz.Retrieved22 March2024.

- ^Nelson Benjamin (28 April 2015)."Sultan wants all Johoreans to unite".The Star.Retrieved26 July2015.

- ^abSusanna Cumming (9 August 2011).Functional Change: The Case of Malay Constituent Order.Walter de Gruyter. pp. 14–.ISBN978-3-11-086454-0.

- ^Peter Borschberg (2016). "Singapore and its Straits, c.1500–1800".Indonesia and the Malay World.45(133).Taylor & Francis:373–390.doi:10.1080/13639811.2017.1340493.S2CID164700929.

- ^Robbie B.H. Goh (1 March 2005).Contours of Culture: Space and Social Difference in Singapore.Hong Kong University Press. pp. 3–.ISBN978-962-209-731-5.

- ^"Johor Sultan: English in danger of becoming older people's language".The Malay Mail.28 December 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 28 March 2016.Retrieved28 March2016.

- ^abc"Johor Bahru, a city on the move".South China Morning Post.31 August 1996. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2015.Retrieved26 July2015.

- ^abAldo Tri Hartono (11 August 2014)."Wisata Belanja di Malaysia, Johor Bahru Tempatnya"(in Indonesian).DetikCom.Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2015.Retrieved26 July2015.

- ^ab"Menikmati Johor Bahru Selangkah dari Singapura"(in Indonesian). Jawa Pos Group. 4 July 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2015.Retrieved9 July2015.

- ^abcd"Flagship A: Johor Bahru City".Iskandar Regional Development Authority.Iskandar Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 27 July 2015.Retrieved27 July2015.

- ^"46th EAROPH Regional Conference, Iskandar, Malaysia, Thistle Hotel, Johor Bahru"(PDF).Eastern Regional Organisation for Planning and Housing.2013. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 July 2015.Retrieved27 July2015.

- ^"8th WIEF Johor Bahru, Malaysia".8th World Islamic Economic Forum. 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 27 July 2015.Retrieved27 July2015.

- ^"Low carbon city report focus on Johor Bahru, Malaysia".British High Commission, Kuala Lumpur.Government of the United Kingdom.17 July 2014.Retrieved27 July2015.

- ^"Malaysian transport, logistics providers welcome change in Woodlands Checkpoint toll charges".The Straits Times. 9 January 2018.Retrieved23 July2018.

- ^"JB calling".The Straits Times. 7 July 2013. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2015.Retrieved20 August2015.

- ^Tash Aw (13 May 2015)."With more Singaporeans in Iskandar, signs of accelerating détente with Malaysia".The New York Times.Retrieved26 July2015.

- ^Zazali Musa (14 July 2015)."Lure of the Singapore dollar".The Star.Retrieved26 July2015.

- ^"More M'sians prefer to earn S'pore wages".Daily Express.15 July 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2015.Retrieved26 July2015.

- ^"Chapter 15: Urban Linkage System (Section B: Planning and Implementation)"(PDF).Iskandar Malaysia. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 July 2015.Retrieved28 July2015.

- ^ab"Larkin Bus Terminal".Express Bus Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 28 July 2015.Retrieved29 July2015.

- ^"Johor Jaya Bus Terminal".Land Transport Guru.September 2015.Retrieved21 July2020.

- ^"Ulu Tiram Bus Terminal".Land Transport Guru.September 2015.Retrieved21 July2020.

- ^"Johor Bahru Taxi".Taxi Johor Bahru. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2015.Retrieved20 August2015.

- ^"From Singapore to KL by train".The Malaysia Site. Archived fromthe originalon 28 July 2015.Retrieved29 July2015.

- ^"Singapore to Malaysia in just 5 minutes? It's now possible".The Straits Times/Asia News Network.Philippine Daily Inquirer.5 July 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2015.Retrieved20 August2015.

- ^abSimon Richmond; Damian Harper (December 2006).Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei. Ediz. Inglese.Lonely Planet. pp. 247–253.ISBN978-1-74059-708-1.

- ^"Malaysia's new airline in $1.5bn deal with Bombardier".BBC News.18 March 2015.Retrieved17 August2015.

- ^John Gilbert (30 October 2015)."October Launch For Flymojo Cancelled".The Malaysian Reserve. Archived fromthe originalon 28 March 2016.Retrieved28 March2016.

- ^"Stulang Laut Ferry Terminal".Easybook.Retrieved23 June2019.

- ^"Direktori Hospital-Hospital Kerajaan"(in Malay). Johor State Health Department. Archived fromthe originalon 3 August 2015.Retrieved3 August2015.

- ^abc"Academic (Clinical) Vacancies"(PDF).Newcastle University Medical School.p. 15. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 23 March 2015.Retrieved3 August2015.

- ^"Direktori Hospital-Hospital Kerajaan"(in Malay). Johor State Health Department. Archived fromthe originalon 3 August 2015.Retrieved3 August2015.

- ^"About Us".KPJ Puteri Specialist Hospital. Archived fromthe originalon 3 August 2015.Retrieved3 August2015.

- ^"Healthcare projects in Iskandar Malaysia".Iskandar Regional Development Authority.Iskandar Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 3 August 2015.Retrieved3 August2015.

- ^"SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH DI NEGERI JOHOR (List of Secondary Schools in Johor) – See Johor"(PDF).Educational Management Information System. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 16 March 2015.Retrieved4 August2015.

- ^"Home"(in Malay). Kolej Penga gian Islam Johor.Retrieved2 August2018.

- ^"Lokasi Perbadanan Perpustakaan Awam Johor"(in Malay). Johor Public Library. Archived fromthe originalon 9 August 2015.Retrieved9 August2015.

- ^"Perpustakaan Cawangan Seluruh Negeri Johor (Public Branches whole over the state of Johor)"(in Malay). Johor Public Library. Archived fromthe originalon 9 August 2015.Retrieved9 August2015.

- ^"Perpustakaan Desa (Village Libraries)"(in Malay). Johor Public Library. Archived fromthe originalon 9 August 2015.Retrieved14 May2013.

- ^Peggy Loh (18 December 2014)."Added advantage".New Straits Times.Retrieved28 March2016.

- ^Lim Mun Fah (10 August 2007)."Rise Up, Foon Yew! Move On, Independent Schools!".Sin Chew Daily.Retrieved2 August2018.

- ^Yee Xiang Yun (19 May 2013)."Great memories as Foon Yew High School turns 100".The Star.Retrieved2 August2018.

- ^abcdef"Lokasi-lokasi Menarik Berhampiran HSAJB (Interesting Spots Near Sultanah Aminah Hospital)"(PDF)(in Malay).Sultanah Aminah Hospital.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 August 2015.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^Natalya (14 April 2013)."Chinese Heritage Museum".Johor Travel. Archived fromthe originalon 18 August 2015.Retrieved18 August2015.

- ^abcdefg"Guide to Iskandar Malaysia's Places of Interests".Iskandar Regional Development Authority.Iskandar Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 18 August 2015.Retrieved20 August2015.

- ^abc"History, Heritage, Arts and Culture, Crafts"(PDF).Malaysian Urological Conference. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 August 2015.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^"Sultan Ibrahim Building".National Archives.Archived fromthe originalon 30 August 2019.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^"Sultan Abu Bakar Mosque".Tourism Malaysia.Archived fromthe originalon 19 August 2015.Retrieved19 August2015.

- ^Desiree Tresa Gasper (2 May 2014)."150-year-old building torn down in middle of the night".The Star.Retrieved19 August2015.

- ^"Johor govt issues writ of summons against Wong Ah Fook mansion owner for demolishment".Antara Pos. 9 May 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 19 August 2015.Retrieved19 August2015.

- ^"Zoo Johor".Tourism Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 21 August 2015.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^Dees Stribling."Zoos in Johor, Malaysia".USA Today.Archived fromthe originalon 21 August 2015.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^"Taman Merdeka Johor Bahru – Visit Malaysia 2020".

- ^"Top 5 Places to Shop in Iskandar Malaysia".Iskandar Regional Development Authority.Iskandar Malaysia. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2015.Retrieved20 August2015.

- ^"About us".Sports Prima. Archived fromthe originalon 4 August 2015.Retrieved4 August2015.

- ^Mohd al Qayum Azizi (12 February 2015)."Best FM Bakal Beroperasi Di KL Awal Tahun Depan"(in Malay). mStar. Archived fromthe originalon 28 March 2016.Retrieved28 March2016.

- ^"FKE Seniors Gained First Hand Experience on Radio Station Operations For Their Capstone Projects".Department of Communication Engineering.Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.4 October 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 28 March 2016.Retrieved28 March2016.

- ^"6,500 Anggota Polis Baharu Setiap Tahun Untuk Atasi Jenayah"(in Malay). mStar. 18 March 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2017.Retrieved8 December2017.

- ^abcJoseph Sipalan (11 November 2013)."Johor posts lower crime rate but capital still a hotspot, says top cop".The Malay Mail. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2017.Retrieved8 December2017.

- ^"Top 10 crime zones in Johor Bahru".AsiaOne. 21 December 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2017.Retrieved8 December2017.

- ^Clarence Fernandez (22 March 2007)."Singapore and Malaysia's Johor – so near, yet so far".Reuters. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2017.Retrieved8 December2017.

- ^abZubairu Abubakar Ghani (2017)."A comparative study of urban crime between Malaysia and Nigeria".Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Environmental Technology, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University.6:19–29.doi:10.1016/j.jum.2017.03.001.hdl:10419/194428.

- ^Farhana Syed Nokman (27 July 2017)."Johor has highest number of rape cases, Sabah tops incest numbers".New Straits Times. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2017.Retrieved8 December2017.

- ^Norbaiti Phaharoradzi (6 April 2016)."Johor cops cripple car-cloning syndicate".The Star.Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2017.Retrieved8 December2017.

- ^Ben Tan (6 October 2015)."JB still stuck with its past sleazy image".The Rakyat Post. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2017.Retrieved8 December2017.

- ^Ng Si Hooi; Gan Pei Ling (17 July 2017)."Foreign call girls look for 'uncles' at JB coffeeshops".The Star.Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2017.Retrieved8 December2017.

- ^"Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia, Johor Bahru".Consulate General of Indonesia, Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia.Retrieved2 July2015.

- ^"Consular Office of Japan (Johor Bahru)".Embassy of Japan in Malaysia.Retrieved5 May2017.

- ^Amanda (10 November 2016)."Changzhou, Johor Bahru of Malaysia become sister-cities".JSChina.cn. Archived fromthe originalon 5 May 2017.Retrieved5 May2017.

- ^Yu Ji (27 August 2011)."Kuching bags one of only two coveted 'Tourist City Award' in Asia".The Star.Archived fromthe originalon 1 July 2015.Retrieved1 July2015.

- ^Helmut K Anheier; Yudhishthir Raj Isar (31 March 2012).Cultures and Globalization: Cities, Cultural Policy and Governance.SAGE Publications. pp. 376–.ISBN978-1-4462-5850-7.

- ^"Relations between Turkey and Malaysia".Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Archived fromthe originalon 30 June 2015.Retrieved1 July2015.

- ^"Home | Christina Sheila JORDAN | MEPs | European Parliament".europarl.europa.eu.Retrieved7 January2020.

- ^Cheah Chor Sooi (7 August 2022)."No pushover Ng Tze Yong has stepped out of Lee Zii Jia's shadow".Focus Malaysia.Retrieved18 August2022.

Further reading[edit]

- Guinness, Patrick (1992).On the Margin of Capitalism: People and development in Mukim Plentong, Johor, Malaysia.South-East Asian social monographs. Singapore: Oxford University Press. p. 177.ISBN978-0-19-588556-9.OCLC231412873.

- Lim, Patricia Pui Huen (2002).Wong Ah Fook: Immigrant, Builder and Entrepreneur.Singapore: Times Editions.ISBN978-981-232-369-9.OCLC52054305.

- Oakley, Mat; Brown, Joshua Samuel (2009).Singapore: city guide.Footscray, Victoria, Australia: Lonely Planet.ISBN978-1-74104-664-9.OCLC440970648.

- Winstedt, Richard Olof; Kim, Khoo Kay (1992).A History of Johore, 1365–1941.M. B. R. A. S. Reprints (6) (Reprint ed.). Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.ISBN978-983-99614-6-1.OCLC255968795.

- John Drysdale (15 December 2008).Singapore Struggle for Success.Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 287–.ISBN978-981-4677-67-7.

- Jamie Han (2014)."Communal riots of 1964".National Library Board.Retrieved5 July2015.

External links[edit]