Johor

Johor | |

|---|---|

| State and Occupied Territories of Johor, the Abode of Dignity Negeri dan Jajahan Takluk Johor Darul Ta'zim نݢري دان جاجهن تعلوق جوهر دارالتّعظيم | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| •Jawi | جوهر |

| •Chinese | Nhu Phật |

| •Tamil | ஜொகூர் Jokūr(Transliteration) |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem:Lagu Bangsa Johor لاݢو بڠسا جوهر Johor State Anthem | |

| |

| Coordinates:1°59′27″N103°28′58″E/ 1.99083°N 103.48278°E | |

| Country | |

| Capital (and largest city) | Johor Bahru[a][3] |

| Royal capital | Muar |

| Government | |

| • Type | Parliamentaryconstitutional monarchy |

| •Sultan | Ibrahim Ismail |

| •Regent | Tunku Ismail |

| •Menteri Besar | Onn Hafiz Ghazi (BN–UMNO) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 19,166 km2(7,400 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,276 m (4,186 ft) |

| Population (2023)[4] | |

| • Total | 4,100,900 (2nd) |

| • Density | 209.2/km2(542/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Johorean / Johorian |

| Demographics(2023)[5] | |

| • Ethnic composition |

|

| • Dialects | Johor-Riau Malay •Terengganu Malay•Jakun•Duano'•Orang Seletar Otherethnic minority languages |

| State Index | |

| •HDI(2022) | 0.794 (high) (10th)[6] |

| •TFR(2017) | 2.1[4] |

| •GDP(2021) | RM131.1 billion,USD29.26 billion[4] |

| •GDP per capita(2021) | RM32,696,USD7,297[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+8(MST[7]) |

| Postal code | |

| Calling code | 07[b] 06 (Muar and Tangkak)[10] |

| ISO 3166 code | MY-01, 21–24[11] |

| Vehicle registration | J[12] |

| Johor Sultanate | 1528 |

| Anglo–Johor Treaty | 1885 |

| Johor State Constitution | 14 April 1895 |

| British protectorate | 1914 |

| Japanese occupation | 31 January 1942 |

| Accession into theFederation of Malaya | 1948 |

| Independence as part of the Federation of Malaya | 31 August 1957 |

| Federated as part ofMalaysia | 16 September 1963 |

| Website | www |

| ^[a]Kota Iskandar,Iskandar Puteriis the state administrative centre and the seat of the Johor state government (executive branch&legislative branch). However,Johor Bahruremains the official capital of the Johor state. ^[b]ExceptMuarandTangkak. | |

Johor(/dʒəˈhɔːr/;Malay pronunciation:[d͡ʒoho(r)],also spelledJohoreor historically,Jahore) is astateofMalaysiain the south of theMalay Peninsula.It borders withPahang,MalaccaandNegeri Sembilanto the north. Johor has maritime borders withSingaporeto the south andIndonesiato the east and west. As of 2023, the state's population is 4.09 million, making it the second most populous state in Malaysia, afterSelangor.[13][14]Johor Bahruis the capital city and the economic centre of the state,Kota Iskandaris the state administrative centre andMuarserves as the royal capital.

Johor's economy is mainly based on theservicesandmanufacturingsectors. Itsgross domestic product(GDP) is among the three largest in Malaysia, alongsideSelangorandKuala Lumpur.Today, Johor remains the nation's largest trade contributor among all Malaysian states.[15]The state is also a major logistics hub in Malaysia, home to thePort of Tanjung Pelepas,the15th busiest port in the world.Johor Bahruis also one of the anchor cities of theIskandar Malaysiadevelopment corridor that covers much of southern Johor, which is the country's first and largestspecial economic zoneby investment value.

Johor has high diversity in ethnicity, culture, and language. The state is known for its traditional dance ofZapinandKuda kepang.The head of state is theSultan of Johor,while the head of government is theMenteri Besar.The government system is closely modelled on theWestminster parliamentary system,with the state administration divided into administrative districts. Islam is thestate religionper the 1895 Constitution of Johor, but other religions can be freely practised.Malayis the official language for the state. Johor has highlydiversetropicalrainforestsand anequatorial climate.Situated at the southern foothills of theTenasserim Hills,inselbergsandmassifsdominate the state's flat landscape, withMount Ledangbeing the highest point.

Etymology

[edit]

The area was first known to the northern inhabitants ofSiamasGangganuorGanggayu(Treasury of Gems)[18][19][20]due to the abundance ofgemstonesnear theJohor River.[21][22]Arabtraders referred to it asجَوْهَر(jauhar),[18][19][23]a word borrowed from thePersianگوهر(gauhar), which also means 'precious stone' or 'jewel'.[24]As the local people found it difficult to pronounce theArabicword in the local dialect, the name subsequently becameJohor.[25]Meanwhile, theOld Javaneseeulogy ofNagarakretagamacalled the areaUjong Medini('land's end'),[17]as it is the southernmost point ofmainland Asia.Another name, through Portuguese writerManuel Godinho de Erédia,made reference toMarco Polo's sailing toUjong Tanah(the end of theMalay Peninsulaland) in 1292.[18]BothUjong MediniandUjong Tanahhad been mentioned since before the foundation of theSultanate of Malacca.Throughout the period, several other names also co-existed such asGaloh,LenggiuandWurawari.[18][25]Johor is also known by its Arabichonorificasدارالتّعظيم(Darul Ta'zim) or 'Abode of Dignity'.[25]

History

[edit]Hindu-Buddhist Era

[edit]A bronze bell estimated to be from 150 AD was found in Kampong Sungai Penchu near theMuar River.[26][27]The bell is believed to have been used as a ceremonial object rather than a trade object as a similar ceremonial bell with the same decorations was found inBattambang province,Cambodia,suggesting that the Malay coast came in contact withFunan,with the bell being a gift from the early kingdom in mainland Asia to local chieftains in the Malay Peninsula.[26][28]Another important archaeological find was the ancient lost city ofKota Gelanggi,which was discovered by following trails described in an old Malay manuscript once owned byStamford Raffles.[29]Artefacts gathered in the area have reinforced claims of early human settlement in the state.[30]The claim of Kota Gelanggi as the first settlement is disputed by the state government of Johor, with other evidence from archaeological studies conducted by the state heritage foundation since 1996 suggesting that the historic city is actually located inKota Tinggi Districtat eitherKota Klang KiuorGanggayu.The exact location of the ancient city is still undisclosed, but is said to be within the 14,000-hectare (34,595-acre) forest reserve where the Lenggiu and Madek Rivers are located, based on records in theMalay Annalsthat, after conqueringGangga Negara,Raja Suran from Siam of theNakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom(Ligor Kingdom) had sailed toGanggayu.[31]Since ancient times, most of the coastal Malay Peninsula has had their own rulers, but all fell under the jurisdiction of Siam.[32]

Sultanate of Johor

[edit]

After thefall of Malaccain 1511 to thePortuguese,the Johor Sultanate was established by SultanMahmud Shah of Malacca's son,Ala'udin Ri'ayat Shah II,in 1528 when he moved the royal court to theJohor Riverand set up his royal residence inJohor Lama.[33][34]Johor became an empire spanning the southern Malay Peninsula,Riau Archipelago(including Singapore),Anambas Islands,Tambelan Archipelago,Natuna Islands,a region around theSambas Riverin south-westernBorneoand Siak inSumatrawithPahang,AruandChampaas allies.[35][36]It aspired to retake Malacca from the Portuguese[37]which theAceh Sultanatein northern Sumatra also aspired to do leading to a three-way war among the rivals.[38]During the wars, Johor's administrative capital moved several times based on military strategies and to maintain authority over trading in the region.[33]Johor and the Portuguese began to collaborate against Aceh, which they saw as a common enemy.[39]In 1582 the Portuguese helped Johor thwart an attack by Aceh, but the arrangement ended when Johor attacked the Portuguese in 1587. Aceh continued its attacks against the Portuguese, and only ceased when a large armada from thePortuguese portinGoacame to defend Malacca and destroy the sultanate.[40]

After Aceh was left weakened, theDutch East India Company(VOC) arrived and Johor formed an alliance with them to eliminate the Portuguese in the 1641capture of Malacca.[41][42]Johor regained authority over many of its former dependencies in Sumatra, such as Siak (1662) and Indragiri (1669), which had fallen to Aceh while Malacca was taken by the Dutch.[40][43]Malacca was placed under the direct control ofBataviain Java.[44]Although Malacca fell under Dutch authority, the Dutch did not establish any further trading posts in the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra, as they had more interest inJavaand theMaluku Islands.[42]The Dutch only become involved with local disputes when theBugisbegan to threaten their maritime trade.[40]

The dynasty that descended from the rulers of Malacca lasted until the death ofMahmud II,when it was succeeded by theBendahara dynasty,a dynasty of ministers who had previously served in the Malacca Sultanate.[33]The Dutch felt increasingly threatened in the 18th century, especially when the EnglishEast India Companystarted to establish a presence in the northern Malay Peninsula,[45]leading the Dutch to seize the Bugis areas ofRiauand expel the Bugis from both Riau andSelangorso these areas would not fall under British rule.[46]This ended Bugis political domination in the Johor-Pahang-Riau empire, resulting in the Bugis being banned from Riau in 1784.[47][48]During the rivalry between the Bugis and Dutch,Mahmud Shah IIIconcluded a treaty of protection with the VOC on board the HNLMSUtrechtand the sultan was allowed to reside in Riau with Dutch protection.[47]Since then, mistrust between the Bugis and Malay escalated.[48]From 1796 to 1801 and from 1807 to 1818, Malacca was placed under BritishResidencyas the Netherlands wereconquered by Francein theNapoleonic Warsand was returned to the Dutch in 1818. Malacca served as the staging area for the BritishInvasion of Javain 1811.[49]

British protectorate

[edit]

When Mahmud Shah III died the sultan left two sons through commoner mothers. While the elder sonHussein Shahwas supported by the Malay community, the younger sonAbdul Rahman Muazzam Shahwas supported by the Bugis community.[48]In 1818, the Dutch recognised Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah as the legitimate heir to the Johor Empire in return for supporting their intention to establish a trading post in Riau.[50]The following year, the British recognised Hussein Shah as the legitimate heir to the Johor Empire in return for supporting their intention to establish a trading post in Singapore.[33][48][51]Before his death, Mahmud Shah III had appointedAbdul Rahmanas theTemenggongfor Johor with recognition from the British as the Temenggong of Johor-Singapore,[33][52][53]marking the beginning of the Temenggong dynasty. Abdul Rahman was succeeded by his son,Daeng Ibrahim,although he was only recognised by the British 14 years later.[33]

With thepartitionof the Johor Empire due to the dispute between the Bugis and Malay and following the defined spheres of influence for the British and Dutch resulting from theAnglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824,Daeng Ibrahim intended to create a new administrative centre for the Johor Sultanate under the new dynasty.[54]As he maintained a close relationship with the British and the latter wanted full control over trade in Singapore, a treaty was signed between Daeng Ibrahim and Hussein Shah's successor,Ali Iskandar,recognising Ali as the next sultan.[55]Through the treaty, Ali was crowned as the sultan and received $5,000 (inSpanish dollars) and an allowance of $500 per month, but was required to cede the sovereignty of the territory of Johor (exceptKesangofMuar,which would be the only territory under his control) to Daeng Ibrahim.[55][56][57]

UnderBritish influence:

UnderBritish influence: UnderDutch influence:

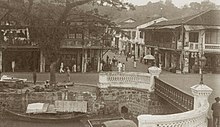

UnderDutch influence:Following the establishment of a new capital in mainland Johor, the administrative centre was moved fromTelok Blangahin Singapore. As the area was still an undeveloped jungle, the Temenggong encouraged the migration ofChineseandJavaneseto clear the land and develop an agricultural economy in Johor. During Daeng Ibrahim's reign, Johor began to be modernised which was continued by his son,Abu Bakar.[33][59]In 1885, an Anglo-Johor Treaty was signed that formalised the close relations between the two, with the British given transit rights for trade through Johor's territory and responsibility for its foreign relations, as well as providing protection to the latter.[50][57]It was also in this year that Johor had formed its present-day boundary.[60]The treaty also provided for the appointment of a British agent in anadvisory role,although no advisor was appointed until 1910.[61]Abu Bakar also implemented a constitution known as theJohor State Constitution(Malay:Undang-undang Tubuh Negeri Johor) and organised his administration in a British style.[62]By adopting an English-style modernisation policy, Johor temporarily prevented itself from being directly controlled by the British, as happened to other Malay states.[63][64]

Under the reign ofIbrahim,the British appointedDouglas Graham Campbellas an advisor to the sultanate in 1910, although the sultan only appointed Campbell as a General Adviser unlike in other Malayan states which had Resident Advisors, becoming the last Malay state to accept a British Adviser.[33]However, due to Ibrahim's overspending, the sultanate faced problems caused by the falling price of its major source ofrevenueand problems between him and members of his state council, which gave the British an opportunity to intervene in Johor's internal affairs.[63]Despite Ibrahim's reluctance to appoint a British adviser, Johor was brought under British control as one of theUnfederated Malay States(UMS) by 1914, with the position of its General Adviser elevated to that of a Resident in theFederated Malay States(FMS).[43][50][57][65]

Second World War

[edit]

Since the 1910s, Japanese planters had been involved in numerous estates and in the mining of mineral resources in Johor as a result of theAnglo-Japanese Alliance.[66][67][68]After theFirst World War,rubbercultivation in Malaya was largely controlled by Japanese companies. Following the abolition of theRubber Lands Restrictions (Enactment)in 1919, Gomu Nanyo Company (South Seas Rubber Co. Ltd.) began cultivating rubber in the interior of Johor.[69]By the 1920s, Ibrahim had become a personal friend ofTokugawa Yoshichika,a member of theTokugawa clanwhose ancestors were military leaders (shōguninJapanese) who ruled Japan from the 16th to the 19th centuries.[67]In theSecond World War,at a great cost of lives in theBattle of Muarin Johor as part of theMalayan Campaign,[70]Imperial Japanese Army(IJA) forces with theirbicycle infantryand tanks advanced into Muar District (present-dayTangkak District) on 14 January 1942.[71]During the Japanese forces' arrival, Tokugawa accompanied GeneralTomoyuki Yamashita's troops and was warmly received by Ibrahim when they reachedJohor Bahruat the end of January 1942.[71]Yamashita and his officers stationed themselves at the Sultan's residence,Istana Bukit Serene,and the state secretariat building,Sultan Ibrahim Building,to plan for theinvasion of Singapore.[72]Some of the Japanese officers were worried since the location of the palace left them exposed to the British, but Yamashita was confident that the British would not attack since Ibrahim was also a friend to the British, which proved to be correct.[67][72]

On 8 February, the Japanese began to bombard the northwestern coastline of Singapore, which was followed by the crossing of the IJA5thand18th Divisionswith around 13,000 troops through theStraits of Johor.[73]The following day, theImperial Guard Divisioncrossed intoKranjiwhile the remaining Japanese Guard troops crossed through the repairedJohor–Singapore Causeway.[73]Following the occupation of all of Malaya and Singapore by the Japanese, Tokugawa proposed a reform plan by which the five kingdoms of Johor, Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah-Penang and Perlis would be restored and federated.[68]Under the scheme, Johor would controlPerak,Selangor,Negeri Sembilanand Malacca while a 2,100-square-kilometre (800 sq mi) area in the southern part of Johor would be incorporated intoSingaporefor defence purposes.[68]The five monarchs of the kingdoms would be obliged to pledge loyalty to Japan, would need to visit the Japanese royal family every two years, and would assure thefreedom of religion,worship, employment andownership of private propertyto all people and accord every Japanese person residing in the kingdoms with treatment equal to indigenous people.[68]

Meanwhile,Ōtani Kōzuiof theNishi Hongan-jisub-sect ofJōdo ShinshūBuddhismsuggested that the sultan system should be abolished and Japan should rule the Malay kingdoms under a Japanese constitutional monarchy government.[68]Japanese War MinisterHideki Tōjō,however, had already reminded their government staff in Malaya to refrain from acting superior to the sultan and to pay respect so the sultan would co-operate with thegunsei(Japanese military organisation).[68]In May, many high-ranking Japanese officials returned toTokyoto consult with officials of the War Ministry and General Staff on how to deal with the Sultan.[68]Upon their return to Singapore in July, they published a document called "A Policy for the Treatment of the Sultan", which was a demand for the Sultan to surrender his power over his people and land to theJapanese emperorthrough the IJA commander. The military organisation demanded the Sultan surrender his power in a manner reminiscent of the way theTokugawa shogunatesurrendered their power to the Japanese emperor in 1868.[68]Through the Japanese administration, many massacres of civilians occurred with an estimate that 25,000 ethnic Chinese civilians in Johor perished during the occupation.[74]In spite of that, the Japanese established the Endau Settlement (also known as the NewSyonanModel Farm) inEndaufor Chinese settlers to ease the food supply problem in Singapore.[75]

Post-war and independence

[edit]

At the start of the war, the British had accepted an offer from theCommunist Party of Malaya (CPM)to co-operate to fight the Japanese; to do this, the CPM formed theMalayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army(MPAJA).[76]The CPM supporters were mostly Chinese-educated members discriminated against by the English-educated elite and theBabas(Straits-born Chinese) during British rule whose main objective was to gain independence from foreign empires and to establish a socialist state based onMarxism–Leninismsimilar to thePeople's Republic of China.[77]The party also had Malay and Indian representatives. They advocated violence as a method of achieving their goals.[77]Throughout their war against the Japanese, they also assassinated civilians suspected of collaborating with the Japanese,[78]while kidnapped Malay women were used ascomfort women,as had also been done by the Japanese.[79]This led to retaliatory raids from some Malays affected by the attacks who decided to collaborate with the Japanese. This indirectly led toethnic conflict,especially when ethnic propaganda was being made by both sides, leading to the deaths of more civilians.[79][80]The Allied forces launchedOperation TideraceandOperation Zipperto liberate Malaya and Singapore. In the five weeks before the British resumed control over Malaya following the Japanese surrender on 16 August 1945, the MPAJA emerged as thede factoauthority in the Malayan territory.[76]

Johor and the rest of Malaya were officially placed under theBritish Military Administration(BMA) in September 1945 and the MPAJA was disbanded in December after its secretary-general,Lai Teck(who was also a double agent for the British),[68][81]accepted the return of British colonial rule and adopted a moderate "open and legal" attitude towards progressing their goals with most members receiving medals from the British the following year.[76][78]There was a dispute after the British had returned when Lai Teck disappeared with the CPM funds. The party administration was taken over byChin Peng,who abandoned the "moderate strategy" in favour of a "people's revolutionary war", culminating in theMalayan Emergencyof 1948.[76]During the emergency period, large-scale attacks by the CPM occurred in the present-dayKulai Districtand other parts of Malaya, but failed to establishMao Zedong-style "liberated areas".[76]

Fighting between the British occupation forces and their Malayan allies against the CPM continued through the formation of theMalayan Unionon 1 April 1946 and the proclamation of the independence of theFederation of Malayaon 31 August 1957.[82]At the time of independence there were three political factions: the Communists, the pro-British, and a race-based coalition. The pro-British side was divided between the Malayan Democratic Union (MDU), which was dominated by English-speaking Chinese and Eurasians who co-operate withleft-wingMalay nationalists "for an independent Malaya that would also include Singapore" and another pro-British side comprising theBabasunder the Straits Chinese British Association (SCBA), who were trying to retain their status and privileges granted for their loyalty to the British during theStraits Settlementsera by remaining under British administration.[77][83][84]Meanwhile, the racial coalition, comprising the leadingUnited Malays National Organisation(UMNO) in analliancewith theMalaysian Indian Congress(MIC) andMalaysian Chinese Association(MCA), sought an independent Malaya based on a racial and religious privileges policy and won the1955 Malayan general election,with the capital of Johor Bahru being the centre of the UMNO party.[48][77]

Malaysia

[edit]In 1961, the Prime Minister of the Federation of MalayaTunku Abdul Rahmandesired to unite Malaya with the British colonies ofNorth Borneo,SarawakandSingapore.[85]Despite growing opposition from the governments ofIndonesiaand thePhilippinesas well from Communist sympathisers and nationalists in Borneo, the federation was realised on 16 September 1963, with the sovereign state renamed Malaysia.[86][87]The Indonesian government later launched a "policy ofconfrontation"towards the new federation,[88]which prompted the United Kingdom and their allies ofAustraliaandNew Zealandto deploy armed forces.[89][90]Pontian Districtbecame the coastal landing point for amphibious Indonesian troops during the confrontation whileLabisandTenanginSegamat Districtbecame the landing point for Indonesian para-commandos for subversion and sabotage attacks.[91][92][93]Several encounters occurred in Kota Tinggi District, where nine Malayan/Singaporean troops and half of the Indonesian infiltrators were killed and the rest were captured.[94]Despite several attacks that also cost civilian lives, the Indonesian side did not reach their main objective, and the confrontation ended in 1966 following the internal political struggle in Indonesia resulting from the30 September Movement.[95][96]

Since the end of the confrontation, the state's development has expanded further with industrial estates and new suburbs. Of the total approved development projects for Johor from 1980 until 1990, 69% were concentrated in Johor Bahru and thePasir Gudangarea.[97]Industrial estates and new suburbs were built in settlements on both the northern and eastern sides of the town, includingPlentongandTebrau.[98]The town of Johor Bahru wasofficially recognised as a cityon 1 January 1994.[98]On 22 November 2017,Iskandar Puteriwas declared a city and assigned as the administrative center of the state, located inKota Iskandar.[99]

Politics

[edit]

Government

[edit]

| |||||

| Affiliation | Coalition/Party Leader | Status | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 election | Current | ||||

| Barisan Nasional | Onn Hafiz Ghazi | Government | 40 | 40 | |

| Pakatan Harapan | Liew Chin Tong | Confidence and supply | 12 | 12 | |

| Perikatan Nasional | Sahruddin Jamal | Opposition | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 56 | 56 | |||

| Government majority | 17 | 23 | |||

Johor is aconstitutional monarchyand was the first state in Malaysia to adopt the system via theJohor State Constitution(Malay:Undang-undang Tubuh Negeri Johor)written by SultanAbu Bakarin 1895.[100][101]The constitutional head of Johor is thesultan.This hereditary position can only be held by a member of theJohor royal familywho is descended from Abu Bakar. The current Sultan of Johor isIbrahim Iskandar,who became sultan on 23 January 2010.[102]The main royal palace for the sultan is theBukit Serene Palace,while the crown prince's is theIstana Pasir Pelangi;both palaces are located in the state capital. Other palaces are theGrand Palace(which is also located in the state capital), Tanjong Palace inMuar,Sri Lambak inKluangand Shooting Box inSegamat.[103]

The state government is headed by aMenteri Besar,who is assisted by an 11-memberexecutive councilselected from the state assembly members.[104]The legislative branch of Johor's government is theJohor State Legislative Assembly,which is based on theWestminster system.Therefore, the chief minister is appointed based on their ability to command the majority of the state assembly. The state assembly makes laws in matters regarding the state. Members of the Assembly are elected by citizens every five years byuniversal suffrage.[105]There are 56 seats in the assembly. The majority (40 seats) are currently held byBarisan Nasional(BN).

Johor was asovereign statefrom 1948 until 1957 while the Federation of Malaya Agreement was in force, but its defence and external affairs were mainly under the control of theUnited Kingdom.[106]The Malayan Federation was then merged with two British colonies in Borneo – North Borneo and Sarawak – to form the Federation of Malaysia. Since then, several disputes have arisen such as the incident involving the state royal family that resulted in the1993 amendments to the Constitution of Malaysia,disputes with federal leaders on state and federation affairs, and dissatisfaction over slower development in contrast with the long-standing prosperity in neighbouring Singapore, which even led to statements aboutsecessionfrom Johor's royal family.[107][108]Other social issues include the rise of racial and religious intolerance among the state's citizens since being part of the federation.[109][110]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Johor is divided into tendistricts(daerah), 103mukimsand 16 local governments.[111][112]There are district officers for each district and a village head person (known as aketua kampungorpenghulu) for each village in the district.[113][114][115]Before the British arrival, Johor was run by a group of relatives and friends of the sultan. A more organised administration was developed in the treaty of friendship with Great Britain in 1885.[116]A British Resident began to be accepted in 1914 when the state became anUnfederated Malay State(UMS).[117]With the transformation into British-style administration, more Europeans were appointed into the administration with their role expanding from advising on financial matters to modern administration guidance.[118]Malay state commissioners worked alongside British district officers, known in Johor as "Assistant Advisers".[119]When the post of the Resident of the UMS was abolished, other European-held posts in the administration were replaced with locals. As in the rest of Malaysia, the local government comes under the purview of the state government.[120]

| Districts | Capital | Area (km2) | Population (2010)[5] | Population (2020) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Batu Pahat | 1,878 | 401,902 | 495,338 | |

| 2 | Johor Bahru | 1,817.8 | 1,334,188 | 1,711,191 | |

| 3 | Kluang | 2,851 | 288,364 | 323,762 | |

| 4 | Kota Tinggi | 3,488 | 187,824 | 222,382 | |

| 5 | Kulai | 753 | 245,294 | 329,497 | |

| 6 | Mersing | 2,838 | 69,028 | 78,195 | |

| 7 | Muar | 1,376 | 239,027 | 314,776 | |

| 8 | Pontian Kechil | 907 | 149,938 | 173,318 | |

| 9 | Segamat | 2,851 | 182,985 | 197,762 | |

| 10 | Tangkak | 970 | 131,890 | 163,449 |

Security

[edit]

The Ninth Schedule of theConstitution of Malaysiastates that theMalaysian federal governmentis solely responsible for foreign policy and military forces in the country.[121]However, Johor has aprivate army,the only state to do so. The retention of the army was one of the stipulations Johor made in 1946 when it participated in theFederation of Malaya.[122]This army, theRoyal Johor Military Force(Askar Timbalan Setia Negeri Johor), has served as the protector of the Johor monarchs since 1886.[123]It is one of the oldest military units in present-day Malaysia and had a significant historical role in the suppression of the1915 Singapore Mutinyand served in both World Wars.[124]

Territorial disputes

[edit]

Johor previously had a territorial dispute with Singapore.[125]In 1979 Government of Malaysia published the Malaysian Territorial Waters and Continental Shelf Boundaries Map which showed the island ofBatu Puteh(present-day Pedra Branca) as under their jurisdiction, Singapore lodged a formal protest the following year.[126]The dispute originally concerned only the one feature, but when both sides agreed to refer the matter to theInternational Court of Justice(ICJ) in 2003, the dispute was enlarged to include two other features in the vicinity,Middle Rocksand South Ledge.[125]In 2008 the ICJ decided that "Batu Puteh belongs to Singapore, Middle Rocks to Malaysia and South Ledge belongs to the state in the territorial waters of which it is located".[127][128]The final decision by ICJ to award Pedra Branca to Singapore was in line with the 1953 letter made by the Acting State Secretary of Johor in response to the question letter regarding Pedra Branca from theColonial Secretary of Singapore,where the Government of Johor openly stated that it did not claim ownership of Pedra Branca despite acknowledging that the old Johor Empire once ruled most of the islands in the area.[129][130]In 2017, Malaysia appealed the case of Pedra Branca based on the conditions required by the ICJ that a case could be revised within six months of discovery of facts and within ten years of the date of judgement following the discovery of several facts.[131]The request was dropped following internal changes in the new Malaysian administration the following year where they subsequently acknowledged Singapore's permanent sovereignty over the island while announcing plans to convert the Middle Rocks into an island.[132][133]

Geography

[edit]

The total land area of Johor is nearly 19,166 square kilometres (7,400 sq mi), and it is surrounded by the South China Sea to the east, the Straits of Johor to the south and theStraits of Malaccato the west.[4]The state has 400 kilometres (250 mi) of coastline,[134]of which 237.7 kilometres (147.7 mi) have beeneroding.[135]A majority of its coastline, especially on the west coast is covered withmangroveandnipahforests.[136][137][138]The east coast is dominated by sand beaches and rockyheadlands,[139]while the south coast consists of a series of alternating headlands andbays.[138]Itsexclusive economic zone(EEZ) extends much further in the South China Sea than in the Straits of Malacca.[140]The western part of Johor had a considerable amount ofpeatland.[141]In 2005, the state recorded 391,499,002 hectares (967,415,102 acres) of forested land, which is classified into natural inland forest,peat swamp forest,mangrove forest andmud flat.[142]About 83% of Johor's terrain islowlands,while only 17% is higher and steep terrain.[142]While being relatively flat, Johor is dotted with many isolated peaks known asinselbergs,including isolatedmassifs.Mount Ledang,also known as Mount Ophir, in the district ofTangkakand near the tripoint withMalaccaandNegeri Sembilan,is the state's highest point at 1,276 metres above sea level.[143]Also in the state are Mount Besar,Mount Belumutand Mount Panti,[144]which form the southern foothills of theTenasserim Hillsthat extends from southernMyanmarandThailand.Since the state also lies on theSunda Plate,it experiences tremors from nearby earthquakes in Sumatra, Indonesia.[145]

Much of central Johor is covered with dense forest, where an extensive network of rivers originating from mountains andhillsin the area spreads to the west, east and south.[146]On the west coast, theBatu Pahat River,Muar Riverand Pontian River flow to theStraits of Malacca,while theJohor River,Perepat River,Pulai River,Skudai RiverandTebrau Riverflow to theStraits of Johorin the south. The Endau River,Mersing River,Sedili Besar Riverand Sedili Kecil River flow to the South China Sea in the east.[142]The Johor River Basin covers an area of 2,690 kilometres, starting fromMount Belumut(east of Kluang) and Mount Gemuruh (to the north) downstream to Tanjung Belungkor.[147]The river originates from the Layang-Layang, Linggiu, and Sayong rivers before converging into the main river and flowing southeast to the Straits of Johor for 122.7 kilometres. Its tributaries include the Berangan River, Lebak River, Lebam River, Panti River, Pengeli River, Permandi River, Seluyut River, Semangar River, Telor River, Tembioh River, and Tiram River.[147]Other river basins in Johor including the Ayer Baloi River, Benut River, Botak Drainage, Jemaluang River, Pontian Besar River, Sanglang River, Santi River, andSarang Buaya River.[148]

Climate

[edit]Johor is located in atropical regionwith anequatorial climate.Both the temperature and humidity are consistently high throughout the year with heavy rainfall. Average monthly temperatures between 26 °C (79 °F) and 28 °C (82 °F), with the lowest recorded during the rainy seasons.[142]The west coast receives an average of between 2,000 millimetres and 2,500 millimetres of rain, while in the east the average rainfall is higher, withEndauandPengerangreceiving more than 3,400 millimetres of rain a year. The state experiences twomonsoonseasons, the northeast and southwest seasons; the northeast occurs from November until March while the southeast occurs from May until September, and the transitional months for the monsoon seasons are April and November.[142]The state experiencedextreme floodingfrom December 2006 to January 2007 with around 60,000–70,000 of the state residents evacuated to an emergency shelter.[149][150]

| Climate data for Johor Bahru (Senai International Airport,2016–2023) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.6 (88.9) |

32.3 (90.1) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

32.3 (90.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 162.6 (6.40) |

139.8 (5.50) |

203.4 (8.01) |

232.8 (9.17) |

215.3 (8.48) |

148.1 (5.83) |

177.0 (6.97) |

185.9 (7.32) |

190.8 (7.51) |

217.7 (8.57) |

237.6 (9.35) |

244.5 (9.63) |

2,355.5 (92.74) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 11 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 162 |

| Source 1: Meteomanz[151] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2:World Meteorological Organisation(precipitation 1974–2000)[152] | |||||||||||||

- Landscapes of Johor

-

Rawa Islandbeach

-

Sunrise over a palm oil plantation

-

Waterfall inMount Belumut

Biodiversity

[edit]

The jungles of Johor host a diverse array of plant and animal species, with an estimated 950vertebratesspecies, comprising 200 mammals, 600 birds and 150 reptiles, along with 2,080invertebratespecies.[142]TheEndau-Rompin National Parkis the largestnational parkin the state, covering an area of 48,905 hectares (120,847 acres) in northern Johor; its name comes from the Endau and Rompin rivers that flow through the park.[153]There are two entry points for the park, one through Peta with an area of 19,562 hectares (48,339 acres) (about 40% of the total area) with entrance fromKahangin the Mersing District and the other at Kampung Selai with an area of 29,343 hectares (72,508 acres) (about 60% of the total area) with entrance fromBekokin Segamat District.[154][155]Destinations in Peta including the Buaya Sangkut Waterfalls, Upeh Guling Waterfalls, Air Biru Lake, Janing Barat, Nature Education and Research Centre (NERC), Kuala Jasin and Peta indigenous village, while in Selai the area is mostly for hiking andjungle trekking.[155][156]Some mammal species found in the park include theAsian elephant,clouded leopard,Malayan sun bear,Malayan tapirandMalayan tiger.[157]

Gunung Ledang National Parkin western Johor, was established in 2005 with an area of 8,611 hectares (21,278 acres).[158]It has various rivers and streams, waterfalls, diverse rainforest,pines,and sub-montane forest,and the Tangkak Dam can also be seen from the park area. Several trails for hiking are available, such as the Asahan Trail, Ayer Panas Trail, Jementah Trail and Lagenda Trail.[158]The state's onlymarine park,the Sultan Iskandar Park, is located off the east coast and is made up of 13 islands in six clusters,Aur,Besar,Pemanggil,Rawa,SibuandTinggi,with an area of more than 8,000 hectares (19,768 acres).[159][160]In 2003, threewetlandsin southern Johor comprisingKukup Island,Pulai River andTanjung Piaiwere designated as aRamsar site.[161]Tanjung Piai covers an area of 526 hectares (1,300 acres) of mangroves and another 400 hectares (988 acres) of inter-tidalmudflats,[162]Pulai River with 9,126.0 hectares (22,551 acres)[163]and Kukup Island with 647 hectares (1,599 acres) surrounded by some 800 hectares (1,977 acres) of mudflats.[164]The Pulai River became aseahorsesanctuary and hatchery as part of the state biodiversity masterplan, since Johor's waters are home to three of the eight seahorse species found in Malaysia.[165]

Poachingis a concern, with the number of wild animals in state parks decreasing with the rise of hunting and fishing in the 2000s.[166]In 2004, local authorities uncovered large-scalesandalwood(gaharu) poaching by foreigners in the Endau-Rompin National Park with a large number of protected plant species being confiscated from the suspects.[167]The conversion of mangrove areas along the southern and eastern coasts for use inaquacultureprojects,sand miningand rapidurbanisationin addition to the abnormal weather patterns caused byclimate changeand rising sea levels are contributing to theerosionof the state's coastline.[168]It has also been discovered that some 68,468 hectares (169,188 acres) of peatland soils in western Johor have been planted withpalm oilplantations.[141]In 2017, around 28 rivers in the state were categorised as polluted,[169]leading the authorities and government to push for legislative change and sterner action against river polluters, especially since severe pollution has disrupted thewater supplyto an estimated 1.8 million people in the state.[170][171]The2019 Kim Kim River toxic pollutionaffected 6,000 residents of the industrial area of Pasir Gudang with 2,775 being hospitalised.[172][173]Forest fireshave also become a concern with more than 380 recorded throughout the state in 2016.[174][175]

Economy

[edit]Johor GDP Share by Sector (2016)[176]

Johor's economy is mainly based on thetertiary sector,namely services, manufacturing, agriculture, construction, etc.[177][178]Johor Corporation(JCorp) is astate-ownedconglomerateinvolved in various business activities in the state and overseas.[179][180]In 2017, thegross domestic product(GDP) of Johor was RM104.4 billion, the third highest among Malaysian states after Selangor and Sarawak, while themedian incomewas RM5,652 and theunemploymentrate was 3.6%.[181]The year before, theeconomic growthrate of the state was 5.7% and accounted for 9.4% of Malaysia's GDP, withGDP per capitaat RM31,952.[182]The state has a total workforce of 1.639 million people.[183]

Prior to economic diversification, thesecondary sectordominated the Johorean economy.[181][186]Johor continues to have a high level of manufacturing investment.[187]From 2013 to 2017, there was a total of RM114.9 billion worth of investment in manufacturing in the state.[188]In 2017, RM16.8 billion came from domestic direct investment and RM5.1 billion came from foreign direct investment, with Australia, China and the United States being the top three foreign investors in manufacturing.[189]The total industrial area in the state as of 2015 was 144 km2(56 sq mi) or 0.75% of the land in Johor.[112]In 2000, the largest industries in Johor weremetal fabricationand machinery industries, accounting for 27.6% of all manufacturing industries in the state, followed by chemical products,petroleumandrubberindustries (20.1%) and wooden products andfurniture(14.1%).[112]

The Iskandar Development Region and South Johor Economic Region (Iskandar Malaysia), encompassing the city centre of Johor Bahru, Iskandar Puteri, Kulai District,Pasir Gudangand South Pontian, is a major development zone in the state with an area of 221,634 hectares (2,216.34 km2).[190][191]Southern Johor focuses ontradingand services; western Johor focuses on manufacturing, business and modernfarming;eastern Johor focuses onecotourism;and central Johor focuses on both ecotourism and the primary sector economy.[183]

The main agricultural sectors in the state arepalm oilplantations, rubber plantations, andproduce.[112]In 2015, land area used for agriculture in Johor covered 11,555 km2(4,461 sq mi), 60.15% of the state, with other plantations includingherbsandspices.[112][192]In 2016, palm oil plantations covered 7,456 km2(2,879 sq mi) (38.8% of the total land area), making it the third largestplantation areain Malaysia afterSabahand Sarawak.[193]Farmers' markets (Malay:pasar peladang) are used to distribute the agricultural produces which are located around the state.[194]

Johor is the biggest fruit producer in Malaysia, with a total fruit plantation area of 414 km2(160 sq mi) and total harvesting area of 305 km2(118 sq mi). Approximately 532,249 tons of fruit was produced in 2016, with Segamat District having the largest major fruit plantation and harvesting area in the state with a total area of 111 km2(43 sq mi) and 66 km2(25 sq mi), respectively, while Kluang District had the highest total fruit production at 163,714 tons. In the same year, Johor was the second biggest producer of vegetables among Malaysian states after Pahang, with a total vegetable plantation area of 154 km2(59 sq mi) and a total harvesting area of 143 km2(55 sq mi). Kluang District also had the largest vegetable plantation and harvesting areas, with a total area of 36 km2(14 sq mi), and the highest total vegetable production at 60,102 tons.[192]

Johor benefits from Singaporean investors and tourists due to its close proximity to Singapore.[108][195][196]From 1990 to 1992, approved Singaporean investments in Johor amounted to about US$500 million in 272 projects.[197]In 1994, the investment from Singapore was nearly 40% of the state's total foreign investment. The state also had a policy of "twinning with Singapore" to promote their industrial development, which increased the movement of people andgoodsbetween the two.[198][199][200]The close economic links between the two began with the establishment of theIndonesia–Malaysia–Singapore Growth Triangle(SIJORI Growth Triangle) in 1989.[201]

In 2014, major foreign countries investing in Johor were Singapore (RM6.7 billion), theUnited States(RM5.4 billion),Japan(RM4.6 billion), theNetherlands(RM3.1 billion),China(RM1.37 billion) and smaller amounts from countries such as Indonesia,South Korea,GermanyandIndia,with the state received RM7.9 billion worth offoreign direct investment(FDI), the second highest among all states in Malaysia afterSarawak.[202]Major foreign companies with FDI in the state come from the United Kingdom, South Korea, and China.[181]Themedical tourismindustry has grown with the arrival of 27,500 medical tourists in 2012 and 33,700 in 2014.[203]

Infrastructure

[edit]

The Johor Department of Economy Planning is responsible for all public infrastructure planning and development in the state,[204]while the Landscape Department is responsible for the state's landscape development.[205]Since theNinth Malaysia Plan,the Johor Southern Corridor has been a focus for development.[206]In 2010, the total state land used forcommercial buildingswas 21.53 km2(8.31 sq mi), withJohor Bahru Districtaccounting for 12.99 km2(5.02 sq mi) or 63.5%.[207]Since 2012, around RM2.63 billion has been allocated by the federal and state governments for 33 infrastructure projects in Pengerang in southeastern Johor.[208]The 2015 state budget included spending more than RM500 million for development in the following year – the highest amount ever allocated.[209]The state government also ensured that infrastructure and development projects would be fairly distributed to all districts in the state,[210]with six focus areas outlined in the state government's strategic development plan in 2018.[211]In the same year, the federal government allocated RM250 million for three infrastructure projects to improve connectivity and accessibility within the state capital.[212]Following the recent change in the state government administration, the new government also pledged to provide better infrastructure for investors by improving the road network, providing an adequate water supply for factories and building sub-stations for electricity generation while rejecting foreign companies after discovering a foreign investor who claimed to use green technology to hide that he intended to use Johor as a waste disposal site.[213][214]

Energy and water resources

[edit]

Electricity distribution in the state is managed byTenaga NasionalBerhad. Most electricity is generated bycoalandgas-fired plants.The coal power plant had a capacity of 700MWin 2007 and 3,100 MW in 2016, which originated from the Tanjung Bin Power Station in Pontian.[215][216][217]Two gas-fired plants, Pasir Gudang Power Station with 210 MW andSultan Iskandar Power Stationwith 269 MW, are located in Pasir Gudang.[218][219]The Pasir Gudang Power Station was retired from the system in 2016.[218]The state government has been planning to constructhydropowerandcombined cyclepower plants since 2015 and 2018 respectively.[220][221]A new combined cycle power plant was constructed on a greenfield site near the old decommissioned power plants in Pasir Gudang, named the Sultan Ibrahim Power Plant.[citation needed]

All water supply pipes in the state are managed by the Water Regulatory Bodies of Johor, with a total of 11 reservoirs: Congok, Gunung Ledang, Gunung Pulai 1, Gunung Pulai 2, Gunung Pulai 3, Juaseh, Layang Lower, Layang Upper, Lebam, Linggiu and Pontian Kechil.[222][223]The state also suppliesraw waterto Singapore for RM0.03 for every 3.8 cubic metres (1,000 US gal) drawn from Johor rivers. In return, the Johor state government pays the Singaporean government 50 cents (RM0.50) for every 3.8 cubic metres of treated water from Singapore.[224]

Telecommunication and broadcasting

[edit]

Telecommunications in Johor were originally administered by the Posts and Telecommunication Department and maintained by the BritishCable & Wireless Communications,which was responsible for all telecommunication services in Malaya.[225][226]During this time, atroposcattersystem was installed on Mount Pulai in Johor and Mount Serapi in Sarawak to connect radio signals betweenBritish MalayaandBritish Borneo,the only such system for both territories to allow simultaneous transmission of radio programs to North Borneo and Sarawak.[227]In 1968, following the foundation of the Federation of Malaysia, the telecommunication departments in Malaya and Borneo merged to form the Telecommunications Department Malaysia, which later becameTelekom Malaysia(TM).[226]Early in 1964,Ericsson–a Nordic telecommunication company– began operating in the country. Following the firstAXE telephone exchangein Southeast Asia that went online in Pelangi in 1980, TM was provided with the first mobile telephone network, named ATUR, in 1984.[228]Since then, the Malaysia's cellular network has expanded rapidly.[229]From 2013 until 2017, the state mobile-cellular penetration rate has reached 100%, with 11.3% to 11.5% of the population using the internet.[230][231]

In 2018, the state internet speed was 10Mbpswith the government urging theMalaysian Communications and Multimedia Commissionto develop high-speed Internet infrastructure to reach 100 Mbit/s to match the state's current rapid development.[232]The Malaysian federal government operates one radio channel –Johor FMthrough its Department of Broadcasting, officially known asRadio Televisyen Malaysia.[233]There is one independent radio station,Best FM,which launched in 1988.[234]Television broadcasting in the state is divided intoterrestrialandsatellite television.There are two types offree-to-airtelevision providers,MYTV Broadcasting(digital terrestrial) andAstro NJOI(satellite), whileIPTVis accessed viaUnifi TVthrough the UniFi fibre optic internet subscription.[235]

Transportation

[edit]Roads

[edit]

The state is linked to the other Malaysian states and federal territories on the western coast through theNorth–South Expresswayand on the eastern coast throughMalaysia Federal Route 3.Since British colonial times, there has been a road system linking Johor's capital in the southern Malay Peninsula toKangarin the north andKota Bharuon the east coast.[236]The roads in Johor are classified into two categories; 2,369 kilometres (1,472 mi) arefederal roadswhile 19,329 kilometres (12,010 mi) arestate roads,as of 2016.[236][237]Johor uses adual carriagewaywith theleft-hand traffic rule,and towns in the state provide public transportation services such as buses and taxis along withGrabservices. TheSungai Johor Bridgeis in Johor, which is the longest central span river-crossing bridge in Malaysia and connectsJohor BahruandKota Tinggi District.In 2018, construction of theIskandar Malaysia Bus Rapid Transitwas announced to be completed before 2021.[238]

The previous federal government had allocated RM29.43 billion as part of theEleventh Malaysia Planfor infrastructure projects including upgrading roads and bridges.[239]The state government also spends over RM600 million on road maintenance annually.[240]

Rail

[edit]

Rail transport in the state is operated byKeretapi Tanah Melayu,which consists ofBatu Anam,Bekok,Chamek,Genuang,Johor Bahru Sentral,Kempas Baru,Kluang,Kulai,Labis,Layang-Layang,Mengkibol,Paloh,Rengam,Senai andTenangrailway stations.[241]The railway line is connected to all of the states in western Peninsular Malaysia. It is also connected to stations inSingaporeandThailand.[242]

Air

[edit]

TheSenai International Airportis the largest and the only international airport in Johor, which acts as the main gateway to the state. The airport is located inSenai Town,Kulai District.In 2016, the Malaysian federal government approved a total of RM7 million in upgrades for the airport.[243][244]Four airlines fly to Johor:AirAsia,Malaysia Airlines,FireflyandBatik Air Malaysia.[245]Other minor airports includingKluang Airport,Mersing Airport,Segamat Airstrip and Batu Pahat Airstrip in Kluang District, Mersing District, Segamat District and Batu Pahat District, respectively.[246]

Water

[edit]

Johor has four ports in Iskandar Puteri and Pasir Gudang, which operate under three different companies. ThePort of Tanjung Pelepasis one of Malaysia's federalcontainer ports.[247]Johor also has two other container ports, the Integrated Container Terminal in Tanjung Pelepas andJohor PortinPasir Gudang.[248][249]TheTanjung Langsat Terminalserves as the state's regional oil and gas hub and supports offshorepetroleumexploration and production.[250][251]There are boat services to ports inBatamandTanjung Pinangof theBintanIslands in Indonesia and to port inChangiinSingapore.[252][253]

Healthcare

[edit]

Health-related matters in Johor are administered by the Johor State Health Office (Malay:Jabatan Kesihatan Negeri Johor). The state has two major government hospitals,Sultanah Aminah HospitalandSultan Ismail Hospital,nine government district hospitals Permai Hospital, Sultanah Fatimah Hospital, Sultanah Nora Ismail Hospital, Enche' Besar Hajjah Khalsom Hospital, Segamat Hospital, Pontian Hospital, Kota Tinggi Hospital, Mersing Hospital, and Tangkak Hospital, and Temenggung Seri Maharaja Tun Ibrahim Hospital, a women's and children's hospital and mental hospital. Other public health clinics,1Malaysia clinicsand rural clinics are scattered throughout the state with a number of private hospitals such as Penawar Hospital, Johor Specialist Hospital, Regency Specialist Hospital, Pantai Hospital Batu Pahat, Putra Specialist Hospital Batu Pahat, Puteri Specialist Hospital, KPJ Specialist Hospital Muar, Abdul Samad Specialist Hospital,Columbia Asia,Gleneagles Medini Hospital and KPJ Specialist Hospital Pasir Gudang.[254]In 2009, the state's doctor–patient ratio was 3 per 1,000 population.[255]

Education

[edit]

All primary and secondary schools are under the jurisdiction of the Johor State Education Department, under the guidance of the nationalMinistry of Education.[256]The oldest school in Johor is theEnglish College Johor Bahru(1914).[257]As of 2013, Johor had a total of 240 government secondary schools,[258]fifteeninternational schools(Austin Heights Private and International Schools,[259]Crescendo-HELP International School,[260]Crescendo International College,[261]Excelsior International School,[262]Paragon Private and International School,[263]Seri Omega Private and International School,[264]Sri Ara International Schools,[265]StarClub Education,[266]Sunway International School,[267]Tenby Schools Setia Eco Gardens,[268]UniWorld International School,[269]and the American School of Iskandar Puteri[270]and three international campuses of BritishMarlborough College,[271]R.E.A.L Schools[272]and Utama Schools),[273]and nineChinese independent schools.Johor has a considerable number of Malay and indigenous students enrolled in Chinese schools.[274]There is also an Indonesian school in the state capital mainly for the children of Indonesian migrants.[275]There are two Japanese learning centres in Johor Bahru.[276]The state government also emphasises pre-school education in the state with the establishment of severalkindergartenssuch as Nuri Kindergarten and Childcare,[277]Stellar Preschool[278]and Tadika Kastil.[279]

Johor has three public universities, theUniversity of Technology MalaysiainSkudai,Tun Hussein Onn University of MalaysiainParit Raja,andUniversiti Teknologi MARA JohorinJementahand the state capital; several polytechnics includingIbrahim Sultan Polytechnicand Mersing Polytechnic; and two teaching colleges, IPG Kampus Temenggong Ibrahim in Johor Bahru and IPG Kampus Tun Hussien Onn in Batu Pahat.[280][281]It has one non-profit community college,Southern University Collegein Skudai.[282]There is also a proposal to establish the University of Johor that has been welcomed by the Sultan of Johor with the federal education ministry also willing to extend their co-operation.[283][284]EduHub Pagoh, the largest public higher education hub area in Malaysia, is being constructed atBandar Universiti Pagoh,a new planned education township in Muar.[285]

To ensure the quality of education in the state, the state government introduced six long-term measures to upgrade the capability of local teachers.[286]In 2018, it was reported that Johor was among several Malaysian states facing a teacher shortage, so the federal education ministry set up a special committee to study ways to tackle the problem.[287]

The Johor State Library is the main public library in the state.[288]

Demography

[edit]Ethnicity and immigration

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 1,277,180 | — | ||

| 1980 | 1,580,423 | +23.7% | ||

| 1991 | 2,069,740 | +31.0% | ||

| 2000 | 2,584,997 | +24.9% | ||

| 2010 | 3,230,440 | +25.0% | ||

| 2020 | 4,009,670 | +24.1% | ||

| ||||

| Source:[289] | ||||

The 2023 Malaysian census reported the population of Johor at 4,100,900, the second most populous state in Malaysia, with a non-citizen population of 276,900.[290]Of the Malaysian residents, 2,464,640 (60.1%) areBumiputera,1,312,128 (32.8%) areChinese,246,054 (6.0%) areIndian.[290]In 2010, the population was estimated to be around 3,348,243, with 1,972,115 (58.9%) Bumiputera, 1,292,421(38.6%) Chinese, 237,725 (7.1%) Indian.[5]Despite the racial diversity of the population, most people in Johor identify themselves as "Bangsa Johor"(English:Johor race), which is also echoed by Johor's royal family to unite the population regardless of ancestry.[291]

As Malaysia is one of theleast densely populated countriesin Asia, the state is particularly sparsely populated, with most people concentrated in the coastal areas, since towns and urban centres have massively expanded through recent developments. From 1991 to 2000, the state experienced a 2.39% average annualpopulation growth,with Johor Bahru District being the highest at 4.59% growth and Segamat District being the lowest at 0.07%.[207]The total population increased by about 600,000 every decade following the increase of residential developments in the southern developmental region; if the pattern continues, Johor will have an estimated 5.6 million people in 2030, larger than the government projection of 4 million.[292]Johor's geographical position in the southern Malay Peninsula has contributed to the state's rapid development as Malaysia's transportation and industrial hub, creating jobs and attracting migrants from other states and overseas, especially from Indonesia, thePhilippines,Vietnam,Myanmar,Bangladesh,India,Pakistanand China. As of 2010, nearly two thirds of foreign workers in Malaysia were located in Johor, Sabah and Selangor.[293]

Religion

[edit]Islam became thestate religionupon the adoption of the 1895 Johor Constitution, although other religions can be freely practised.[295]According to the 2020 Malaysian census the religious affiliation of Johor's population was 58.7%Muslim,25.9%Buddhist,8.2%Christian,6%Hindu,0.1% followers of other religions or unknown affiliations, 0.2%TaoistorChinese folk religionadherents, and 0.2% non-religious.[294]The census indicated that 80.2% of the Chinese population in Johor identified as Buddhists, with significant minorities identifying as Christians (18.2%), Chinese folk religion adherents (1.6%) and Muslims (0.2%). The majority of the Indian population identified as Hindus (73.5%), with significant minorities identifying as Christians (6.1%), Muslims (9.2%) and Buddhists (2.8%). The non-Malay bumiputera community was predominantly Christians (68.3%), with significant minorities identifying as Muslims (21.6%) and Buddhists (15%). Among the majority population, all Malay bumiputera identified as Muslims.[294]

Languages

[edit]

The majority of Johoreans are at least bilingual, withMalayas the official language in Johor.[296]Other multilingual speakers may also be fluent inChineseandTamillanguages.[297]

Johorean Malay, also known as Johor-Riau Malay and originally spoken in Johor,Riau,Riau Islands,Malacca,SelangorandSingapore,has been adopted as the basis for both theMalaysianandIndonesiannational languages.[298]Due to Johor's location at the confluence of trade routes withinMaritime Southeast Asiaas well as its history as an influential empire, the dialect has spread as the region'slingua francasince the 15th century; hence the adoption of the dialect as the basis for the national languages ofBrunei,Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.[299]Several related languages are also spoken in Johor such asOrang Seletar(spoken along the Straits of Johor and in northern Singapore),Orang Kanaq(spoken in small parts of southeastern Johor),Jakun(spoken mostly in inland parts of Johor),Temuan(spoken near the border with Pahang and Negeri Sembilan) andOrang Kuala(spoken along the northwest coast of Johor).Terengganu Malay,a distinct variant of Malay, is spoken in the district ofMersingnear the border withRompin,Pahang.[300]

Differentdialect groupsof the Chinese language are spoken among the Chinese community in the state, includingHokkien,Teochew,Hakka,Cantonese,andHainanese.

The Indian community predominantly speaks Tamil. There is also a significant number ofMalayaleepopulations in parts ofSegamat,Johor BahruandMasai,who speakMalayalamas their mother tongue. Moreover, small number of other Indian language speakers such as theTelugu,andPunjabilanguage speakers are also present. ManyMalayaleesandTelugusare often categorised as Tamils by the Tamils themselves, and by other groups, as they use the Tamil language as alingua francaamong other Indian communities.[citation needed]

In 2017, the Queen of Johor, as the royal patron of the Malaysian English Language Teaching Association, called for a more conducive environment for young Malaysians to master English since there has been a drastic decline in proficiency among the younger Malaysian generation.[301][302]

Culture

[edit]

Johor's culture has been influenced by different ethnicities throughout history, especially by the Arabs, Bugis and Javanese people, with the state also becoming a mixture of different cultures among the Chinese, Indian, Malay and aboriginal people.[303]

A strongArab culturalinfluence is apparent in art performances likezapin,masriandhamdolokand in musical instruments like thegambus.[304][305]Thezapindance was introduced in the 14th century by Arab Muslim missionaries fromHadhramaut,Yemen,and was originally performed only by male dancers, although female dancers are now common.[306]The dance itself differs among five Johor regions, namelyzapin tengluandzapin pulau(Mersing),zapin lenga(Muar),zapin pekajang(Johor Bahru),zapin koris(Batu Pahat) andzapin parit mustarwithzapin seri bunian(Pontian).[306]Another Arab legacy is the use of Arabic names withwadi(valley) for areas populated by the Arab community in the state capital such as "wadi hana"and"wadi hassan".[307]

Buginese andJavanesecultural influences are found in thebosaraandkuda kepangdances introduced to Johor before the early 20th century by immigrants of respective communities.[308][309]The influence ofJavanese languageon the local Malay dialect is also noticeable from particular vocabulary collected in recorded observations.[310]Indian culture inspired theghazal.These cultural activities are normally performed at Malay weddings and religious festivals.[305]The aboriginal culture is also unique with a diversity of traditions still practised, such as the making of traditional weapons, medicines,handicraftsandsouvenirs.[311]

The Chinese community holds theChingay paradeannually by theJohor Bahru Old Chinese Temple,which unites the five Chinese ethnic groups in Johor, namelyCantonese,Hainanese,Hakka,HokloandTeochew.[312]This co-operation among different Chinese cultures under a voluntary organisation became a symbol of harmony among the different Chinese people that deepens their sense of heritage to preserve their cultural traditions.[313]TheJohor Bahru Chinese Heritage Museumdescribes the history of Chinese migration into Johor from the 14th to 19th centuries during theMingandQingdynasties. The ruler of Johor encouraged the Chinese community to plantgambierandpepperin the interior; many of these farmers switched topineapplecultivation in the 20th century, making Johor one of Malaysia's top fruit producers.[314]

Cuisine

[edit]

Cuisine in Johor has been influenced by Arab, Buginese, Javanese, Malay, Chinese and Indian cultures. Notable dishes includenasi lemak,asam pedas,Nasi Beringin,cathaylaksa,cheesemurtabak,Johor laksa,kway teow kia,mee bandung,mee rebus,Muarsatay,pineapple pajeri, Pontianwonton noodle,san lou friedbee hoon,otak-otak,telur pindang,[315][316]and other mixed Malay dishes.[317]Popular desserts includeburasak,[317]kacang pool,lontongand snacks likebanana cake,Kluang toasted buns andpisang goreng.[316][318]International restaurants offeringWestern,Filipino,Indonesian,Japanese,Korean,Taiwanese,ThaiandVietnamesecuisines are found throughout the state, especially in Johor Bahru andIskandar Puteri.[319]

Holidays and festivals

[edit]Johoreans observe a number of holidays and festivals throughout the year includingIndependence Day,Malaysia Daycelebrations and the Sultan of Johor's Birthday.[320]Additional local and international festivals held annually in the state capital include the Japanesebon odori,kuda kepangand kite and art festivals.

Sports

[edit]

As Johor has been part of Malaya since 1957, its athletes represented Malaya and later Malaysia at theSummer Olympic Games,Commonwealth Games,Asian Games,andSoutheast Asian Games.The Johor State Youth and Sports Department was established in 1957 to raise the standard of sports in the state.[321]Johor hosted theSukma Gamesin 1992. There are four sports complexes in the state,[322]and the federal government also provides aid to improve sports facilities.[323]In 2018, as part of a federal government plan to turn Muar into Johor's sports hub, around RM15 million has been allocated to build and upgrade sports facilities in the town.[324]

Located inIskandar Puteri,theSultan Ibrahim Stadiumis the main stadium of the football clubJohor Darul Ta'zim.They have won theMalaysia FA Cupand theMalaysia Cupfour times each, theMalaysia Super Leaguefor ten consecutive seasons between 2014 and 2023,[325]and theAFC Cupin 2015.[326][327][328]The state women's football team also won four titles in theTun Sharifah Rodziah Cupin 1984, 1986, 1987 and 1989. Another notable stadium in the state isPasir Gudang Corporation StadiuminPasir Gudang.[329]Johor also launched its ownesportsleague, becoming the second Malaysian state to introduce the sport to the Sukma Games, with the Johor Sports Council agreeing to include it in the2020 edition.[330][331]

Notable people

[edit]- Yasmin Ahmad

- Hishamuddin Hussein

- Hussein Onn

- Noraniza Idris

- Onn Jaafar

- Zulhadi Omar

- Seah Jim Quee

- Syed Saddiq

- Muhyiddin Yassin

References

[edit]- ^abc"Maklumat Kenegaraan (Negeri Johor Darul Ta'zim)"[Statehood Information (State of Johor Darul Ta'zim)] (in Malay).Ministry of Communications and Multimedia (Malaysia).Archived fromthe originalon 8 July 2018.Retrieved8 July2018.

- ^Mohd Farhaan Shah Farhaan (23 March 2016)."A rich legacy".Star2.Retrieved8 July2018– viaPressReader.

- ^"MAIN INDICATOR IN M.B. JOHOR BAHRU".MyCenDash.Retrieved3 July2022.

- ^abcdef"Johor @ a Glance".Department of Statistics, Malaysia.Retrieved13 January2018.

- ^abcd"Total population by ethnic group, administrative district and state, Malaysia"(PDF).Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 2010. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 February 2012.Retrieved23 July2018.

- ^"Subnational Human Development Index (2.1) [Johor – Malaysia]".Global Data Lab of Institute for Management Research,Radboud University.Retrieved12 November2018.

- ^Helmer Aslaksen (28 June 2012)."Time Zones in Malaysia".Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science,National University of Singapore.Archived fromthe originalon 21 May 2016.Retrieved8 July2018.

- ^"Postal codes in Johor".cybo.Retrieved8 July2018.

- ^"Postal codes in Kluang".cybo.Retrieved8 July2018.

- ^"Area codes in Johor".cybo.Retrieved8 July2018.

- ^"State Code".Malaysian National Registration Department. Archived fromthe originalon 19 May 2017.Retrieved8 July2018.

- ^Teh Wei Soon (23 March 2015)."Some Little Known Facts On Malaysian Vehicle Registration Plates".Malaysian Digest. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015.Retrieved8 July2018.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^"penemuan utama banci penduduk dan perumahan malaysia, 2020"(PDF).Banci 2020.

- ^"Johor – Info Malaysia (IIM) Leading Industrial, Commercial, Tourism & Information in Malaysia".iim.my.Retrieved26 December2023.

- ^BERNAMA (11 August 2023)."JOHOR RECORDS TOTAL TRADE OF RM563.31 BLN TO SEPTEMBER, REMAINS COUNTRY'S LARGEST TRADE CONTRIBUTOR".BERNAMA.Retrieved4 December2023.

- ^S. Durai Raja Singam (1962).Malayan Place Names.Liang Khoo Printing Company.

- ^abJohn Krich (8 April 2015)."Johor: Jewel of Malaysia".National Geographic.Archived fromthe originalon 24 April 2017.Retrieved24 June2018.

- ^abcd"Ancient names of Johor".New Straits Times.21 February 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 21 February 2009.Retrieved13 January2018.

- ^abTang Ruxyn (26 April 2017)."The Stories And Facts Behind How The 13 States Of Malaysia Got Their Names".Says.Archived fromthe originalon 13 January 2018.Retrieved13 January2018.

- ^"Facts About Johor".Johor Tourism. Archived fromthe originalon 27 July 2018.Retrieved27 July2018.

- ^Abdul Latip bin Talib (14 July 2014).Moyang Salleh[Salleh Great-grandparent] (in Malay). PTS Litera Utama. pp. 34–.ISBN978-967-408-158-4.

- ^"The origins of the word Johor".Johor Darul Ta'zim F.C.Archived fromthe originalon 13 January 2018.Retrieved13 January2018.

- ^"Johor History".Johor State Investment Centre. 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 31 August 2011.Retrieved13 January2018.

- ^Jonathan Rigg (1862).A dictionary of the Sunda language of Java.Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen. pp. 177–.

- ^abc"Origin of Place Names – Johor".National Library of Malaysia.2000. Archived fromthe originalon 9 February 2008.Retrieved13 January2018.

- ^abMichel Jacq-Hergoualc'h (2002).The Malay Peninsula: Crossroads of the Maritime Silk-Road (100 Bc-1300 Ad).BRILL. pp. 77–.ISBN978-90-04-11973-4.

- ^P. Boomgaard (2007).Southeast Asia: An Environmental History.ABC-CLIO. pp. 47–.ISBN978-1-85109-419-6.

- ^Leong Sau Heng (1993)."Ancient Trading Centres in the Malay Peninsula".Malaysian Archaeology Journal,University of Malaya.National University of Malaysia. pp. 2 and 8. Archived fromthe originalon 15 January 2018.Retrieved15 January2018.

- ^"Manuscript leads to lost city".The Star.3 February 2005. Archived fromthe originalon 14 January 2018.Retrieved14 January2018.

- ^Teoh Teik Hoong; Audrey Edwards (4 February 2005)."Johor relics predate Malacca".The Star.Archived fromthe originalon 14 January 2018.Retrieved14 January2018.

- ^Mazwin Nik Anis (8 February 2005)."Lost city is 'not Kota Gelanggi'".The Star.Archived fromthe originalon 14 January 2018.Retrieved14 January2018.

- ^Anthony Reid; Barbara Watson Andaya; Geoff Wade; Azyumardi Azra; Numan Hayimasae; Christopher Joll; Francis R. Bradley; Philip King; Dennis Walker; Kobkua Suwannathat-Pian; Iik A. Mansurnoor; Duncan McCargo (1 January 2013).Ghosts of the Past in Southern Thailand: Essays on the History and Historiography of Patani.NUS Press. pp. 74–.ISBN978-9971-69-635-1.

- ^abcdefgh"History of the Johor Sultanate".Coronation of HRH Sultan Ibrahim. 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 2 July 2015.Retrieved14 January2018.

- ^Borschberg, Peter (11 January 2016). "Johor-Riau Empire".The Encyclopedia of Empire.Wiley Online Library.pp. 1–3.doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe105.ISBN9781118455074.

- ^Ooi Keat Gin; Hoang Anh Tuan (8 October 2015).Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1350–1800.Routledge. pp. 136–.ISBN978-1-317-55919-1.

- ^"Letter from King of Johor, Abdul Jalil Shah IV (r. 1699-1720), to Governor-General Abraham van Riebeeck, 26 April 1713".National Archives of Indonesia.Retrieved25 June2018.

- ^John Anderson (1824).Political and commercial considerations relative to the Malayan peninsula, and the British settlements in the straits of Malacca.pp. 25–.

- ^M.C. Ricklefs (1981). "The Rise of New States, c. 1500–1650".A History of Modern Indonesia.Palgrave Macmillan,Springer Science+Business Media.pp. 29–46.doi:10.1007/978-1-349-16645-9_4.ISBN978-0-333-24380-0.

- ^Paulo Jorge Sousa Pinto (1996)."Melaka, Johor and Aceh: A bird's eye view over a Portuguese-Malay Triangular Balance (1575–1619)"(PDF).Files of the Calouste Gulbenkian Cultural Centre, Composite, Printed and Stitched in Graphic Arts Workshops & Xavier Barbosa, Limited, Braga.Academia.edu:109–112.Retrieved15 January2018.

- ^abcM.C. Ricklefs; Bruce Lockhart; Albert Lau; Portia Reyes; Maitrii Aung-Thwin (19 November 2010).A New History of Southeast Asia.Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 150–151.ISBN978-1-137-01554-9.Archived fromthe originalon 17 June 2016.

- ^Peter Borschberg (2009)."The Johor-VOC Alliance and the Twelve Years' Truce: Factionalism, Intrigue and International Diplomacy".National University of Singapore(IILJ Working Paper 2009/8, History and Theory of International Law Series ed.). Institute for International Law and Justice,New York University School of Law.Retrieved25 June2018.

- ^abMichael Percillier (7 September 2016).World Englishes and Second Language Acquisition: Insights from Southeast Asian Englishes.John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 8–.ISBN978-90-272-6665-1.

- ^abOoi Keat Gin (18 December 2017).Historical Dictionary of Malaysia.Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 217–218.ISBN978-1-5381-0885-7.

- ^Dennis De Witt (2008).History of the Dutch in Malaysia: In Commemoration of Malaysia's 50 Years as an Independent Nation and Over Four Centuries of Friendship and Diplomatic Ties Between Malaysia and the Netherlands.Nutmeg Publishing. pp. 11–.ISBN978-983-43519-0-8.

- ^A. GUTHRIE (of the Straits Settlements, and OTHERS.) (1861).The British Possessions in the Straits of Malacca. [An Address to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Signed by A. Guthrie and Others, and Dated April 20th, 1861, in Reference to the Transfer of the Administration of the British Possessions in the Straits of Malacca to the Colonial Office.].pp. 1–.

- ^Robert J. Antony (1 October 2010).Elusive Pirates, Pervasive Smugglers: Violence and Clandestine Trade in the Greater China Seas.Hong Kong University Press. pp. 129–.ISBN978-988-8028-11-5.

- ^abAruna Gopinath (1991).Pahang, 1880-1933: a political history.Council of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.ISBN9789839961423.

- ^abcdeOoi Keat Gin (2004).Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor.ABC-CLIO. pp. 699 and 1365.ISBN978-1-57607-770-2.

- ^Michael Leifer (1 January 1978).Malacca, Singapore, and Indonesia.BRILL. pp. 9–.ISBN978-90-286-0778-1.

- ^abcBibliographic Set (2 Vol Set). International Court of Justice, Digest of Judgments and Advisory Opinions, Canon and Case Law 1946 – 2011.Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. June 2012. pp. 1448–.ISBN978-90-04-23062-0.

- ^Nor-Afidah (14 December 2004)."Sultan Hussein Shah".National Library Board,Singapore. Archived fromthe originalon 21 January 2018.Retrieved21 January2018.

•Nor-Afidah (15 May 2014)."1819 Singapore Treaty [6 February 1819]".National Library Board, Singapore. Archived fromthe originalon 21 January 2018.Retrieved21 January2018. - ^Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.The Branch. 1993. pp. 7–.

- ^Kevin YL Tan (30 April 2015).The Constitution of Singapore: A Contextual Analysis.Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 12–.ISBN978-1-78225-809-4.

- ^M. A. Fawzi Mohd. Basri (1988).Johor, 1855–1917: pentadbiran dan perkembangannya[Johor, 1855–1917: its administration and development] (in Malay). Fajar Bakti.ISBN978-967-933-717-4.

- ^abAbdul Ghani Hamid (3 October 1988)."Tengku Ali serah Johor kepada Temenggung (Kenangan Sejarah)"[Tengku Ali surrenders Johor to Temenggung (Historical Flashback)] (in Malay).Berita Harian.Retrieved30 June2015.

- ^"Johor Treaty is signed [10 March 1855]".National Library Board, Singapore. Archived fromthe originalon 21 January 2018.Retrieved21 January2018.

- ^abcC. M. Turnbull(16 October 2009). "British colonialism and the making of the modern Johor monarchy".Indonesia and the Malay World.37(109).Taylor & Francis:227–248.doi:10.1080/13639810903269227.S2CID159776294.

- ^Peter Turner; Hugh Finlay (1996).Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei.Lonely Planet Publications.ISBN978-0-86442-393-1.

- ^A Rahman Tang Abdullah (2008)."Modernisation or Westernisation of Johor under Abu Bakar: A Historical Analysis".International Islamic University Malaysia.pp. 209–231.Retrieved9 April2018.

- ^Trocki, Carl A. (2007).Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784–1885.Singapore: NUS Press. p. 22.ISBN978-9971-69-376-3.

- ^Natasha Hamilton-Hart (2003).Asian States, Asian Bankers: Central Banking in Southeast Asia.Singapore University Press. pp. 102–.ISBN978-9971-69-270-4.

- ^Muzaffar Husain Syed; Syed Saud Akhtar; B D Usmani (14 September 2011).Concise History of Islam.Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. pp. 316–.ISBN978-93-82573-47-0.

- ^abZaemul Zamhari Ibrahim (2017)."Examine the reason why Sultan of Johor finally accepted a British advisor in 1914".Universiti Brunei Darussalam.pp. 2–5.Retrieved11 April2018.

- ^Simon C. Smith (10 November 2008). "Conflict and collaboration [Britain and Sultan Ibrahim of Johor]".Indonesia and the Malay World.36(106). Taylor & Francis: 345–358.doi:10.1080/13639810802450357.S2CID159365395.

- ^"Johor is brought under British control [11 May 1914]".National Library Board, Singapore. Archived fromthe originalon 9 April 2018.Retrieved9 April2018.

- ^さや・ bạch thạch; Takashi Shiraishi (1993).The Japanese in Colonial Southeast Asia.SEAP Publications. pp. 13–.ISBN978-0-87727-402-5.

- ^abcPatricia Pui Huen Lim; Diana Wong (2000).War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore.Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 143–144.ISBN978-981-230-037-9.

- ^abcdefghiYōji Akashi; Mako Yoshimura (1 December 2008).New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation in Malaya and Singapore, 1941-1945.NUS Press. pp. 26, 42, 43, 44, 70, 126 and 220.ISBN978-9971-69-299-5.

- ^Uqbah Iqbal (12 October 2016).The Historical Development of Japanese Investment in Malaysia (1910–2003).GRIN Verlag. pp. 16–.ISBN978-3-668-31937-0.

- ^Christopher Alan Bayly; Timothy Norman Harper (2005).Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941–1945.Harvard University Press. pp. 129–.ISBN978-0-674-01748-1.