Karate

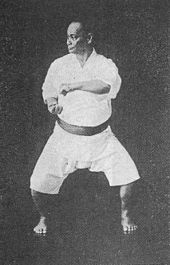

Chōmo Hanashiro,an Okinawan karate masterc. 1938 | |

| Also known as | Karate-do (Karate) |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking |

| Hardness | Full-contact,semi-contact,light-contact |

| Country of origin | Ryukyu Kingdom(Present dayOkinawa prefecture, |

| Parenthood | Kenpo,Indigenous martial arts of Ryukyu Islands,Chinese martial arts[1][2] |

| |

| Highestgoverning body | World Karate Federation |

|---|---|

| First developed | Ryukyu Kingdom,ca.17th century |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Yes |

| Mixed-sex | Varies |

| Type | Martial art |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | 2020 |

| World Games | 1981– present |

Karate(Tay không)(/kəˈrɑːti/;Japanese pronunciation:[kaɾate];Okinawanpronunciation:[kaɽati]), alsokarate-do(Karate,Karate-dō),is amartial artdeveloped in theRyukyu Kingdom.It developed from theindigenous Ryukyuan martial arts(calledte(Tay),"hand";tīin Okinawan) under the influence ofChinese martial arts.[1][2]While modern karate is primarily a striking art that uses punches and kicks, traditional karate also employsthrowingandjoint lockingtechniques.[3]A karate practitioner is called akarate-ka(Tay không gia).

The Ryukyu Kingdom had been conquered by the JapaneseSatsuma Domainand had become itsvassal statesince 1609, but was formally annexed to theEmpire of Japanin 1879 asOkinawa Prefecture.The Ryukyuansamurai(Okinawan:samurē) who had been the bearers of karate lost their privileged position, and with it, karate was in danger of losing transmission. However, karate gradually regained popularity after 1905, when it began to be taught in schools in Okinawa. During theTaishō era(1912–1926), karate was introduced to mainland Japan byGichin FunakoshiandMotobu Chōki.Karate's popularity was initially sluggish with little exposition but when a magazine reported a story about Motobu defeating a foreign boxer in Kyoto, karate rapidly became well known throughout Japan.[4]

In this era of escalatingJapanese militarism,[5]the name was changed fromĐường tay( "Chinese hand" or "Tanghand ")[6]toTay không( "empty hand" ) – both of which are pronouncedkaratein Japanese – to indicate that the Japanese wished to develop the combat form in Japanese style.[7]After World War II, Okinawa became (1945) an important United States military site and karate became popular among servicemen stationed there.[8][9]Themartial arts moviesof the 1960s and 1970s served to greatly increase the popularity of martial arts around the world, and English-speakers began to use the wordkaratein a generic way to refer to all striking-basedAsian martial arts.[10]Karate schools (dōjōs) began appearing around the world, catering to those with casual interest as well as those seeking a deeper study of the art.

Karate, like other Japanese martial arts, is considered to be not only about fighting techniques, but also about spiritual cultivation.[11][12]Many karate schools anddōjōshave established rules calleddōjō kun,which emphasize the perfection of character, the importance of effort, and respect for courtesy. Karate featured at the2020 Summer Olympicsafter its inclusion at the Games was supported by theInternational Olympic Committee.Web Japan (sponsored by theJapanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs) claims that karate has 50 million practitioners worldwide,[13]while theWorld Karate Federationclaims there are 100 million practitioners around the world.[14]

Etymology[edit]

Originally in Okinawa during the Ryukyu Kingdom period, there existed an indigenous Ryukyuan martial art calledte(Okinawan:tī,lit. 'hand'). Furthermore, in the 19th century, a Chinese-derived martial art calledtōde(Okinawan:tōdī,lit. 'Tang hand') emerged. According to Gichin Funakoshi, a distinction betweenOkinawan-teandtōdeexisted in the late 19th century.[15]With the emergence oftōde,it is thought thattealso came to be calledOkinawa-te(Okinawan:Uchinādī,lit. 'Okinawa hand'). However, this distinction gradually became blurred with the decline ofOkinawa-te.

Around 1905, whenkaratebegan to be taught in public schools in Okinawa,tōdewas readkun’yomiand calledkarate(Đường tay,lit. 'Tang hand') in the Japanese style. Bothtōdeandkarateare written in the same Chinese characters meaning "Tang/China hand," but the former ison'yomi(Chinese reading) and the latter is kun'yomi (Japanese reading). Since the distinction betweenOkinawa-teandtōdewas already blurred at that time, karate was used to encompass both. "Kara (から)" is akun’yomifor the character "Đường" (tō/とう inon'yomi) which is derived from "Gaya Confederacy( thêm la ) "and later included things deriving fromChina(specifically from theTang dynasty).[16]Therefore,tōdeandkarate(Tang hand) differ in the scope of meaning of the words.[17]

Japan sent envoys to the Tang dynasty and introduced much Chinese culture. Gichin Funakoshi proposed thattōde/karate may have been used instead ofte,as Tang became a synonym for luxury imported goods.[18]

According to Gichin Funakoshi, the word pronounced karate(から tay)existed in the Ryukyu Kingdom period, but it is unclear whether it meant Tang hand(Đường tay)or empty hand(Tay không).[19]

However, this name change did not immediately spread among Okinawan karate practitioners. There were many karate practitioners, such asChōjun Miyagi,who still usedtein everyday conversation until World War II.[20]

When karate was first taught in mainland Japan in the 1920s, Gichin Funakoshi and Motobu Chōki used the namekarate-jutsu(Đường giải phẫu,lit. 'Tang hand art') along with karate.[21][22]The wordjutsu(Thuật) means art or technique, and in those days it was often used as a suffix to the name of each martial art, as injujutsuandkenjutsu(swordsmanship).[23]

The first documented use of ahomophoneof thelogogrampronouncedkaraby replacing theChinese charactermeaning "Tang dynasty" with the character meaning "empty" took place inKarate Kumite(Tay không tổ tay) written in August 1905 byChōmo Hanashiro(1869–1945).[24]In mainland Japan, karate (Tay không,empty hand) gradually began to be used from the writings of Gichin Funakoshi and Motobu Chōki in the 1920s.[25][26]

In 1929, the Karate Study Group ofKeio University(Instructor Gichin Funakoshi) used this term in reference to the concept of emptiness in theHeart Sutra,and this terminology was later popularized, especially in Tokyo. There is also a theory that the background for this name change was the worsening of Japan-China relations at the time.[27]

On October 25, 1936, a roundtable meeting of karate masters was held in Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, and it was officially resolved to use the name karate (empty hand) in the sense ofkūshu kūken(Tay không không quyền,lit. 'without anything in the hands or fists').[28]To commemorate this day, the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly passed a resolution in 2005 to decide October 25 as "Karate Day."[29]

Another nominal development is the addition ofdō(Nói;どう) to the end of the word karate.Dōis a suffix having numerous meanings including road, path, route and way.[30]It is used in many martial arts that survived Japan'stransitionfromfeudal culturetomodern times.It implies that these arts are not just fighting systems but contain spiritual elements when promoted as disciplines.[31]In this contextdōis usually translated as "the way of…". Examples includeaikido,judo,kyūdōandkendo.Thus karatedō is more than just empty hand techniques. It is "the way of the empty hand".[32]

Since the 1980s, the term karate (カラテ) has been written inkatakanainstead of Chinese characters, mainly byKyokushinKarate (founder:Masutatsu Oyama).[33]In Japan, katakana is mainly used for foreign words, giving Kyokushin Karate a modern and new impression.

| 15th – 18th century | 19th century | 1900s – | 1920s – | 1980s – | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Te(hand) | TeorOkinawa-te | Karate(Tang hand) | Karate(-jutsu) | Karate(Empty hand) | Karate(カラテ) |

| Tōde(Tang hand) | |||||

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

There are several theories regarding the origins of karate, but the main ones are as follows.

Theory of development frommēkata[edit]

In Okinawa, there was an ancient martial dance calledmēkata(Vũ phương). The dancers danced to the accompaniment of songs andsanshinmusic, similar to karate kata. In the Okinawan countryside,mēkataremained until the early 20th century. There is a theory that from thismēkatawith martial elements,te(Okinawan:tī,hand) was born and developed into karate. This theory is advocated byAnkō Asatoand his student Gichin Funakoshi.[34]

Theory of introduction by thirty-six families from Min[edit]

It is said that in 1392, a group of professional people known as the "Thirty-six families from Min"migrated toKume Village(now Kume, Naha City) in Naha from Fu gian Province in the Ming Dynasty at that time. They brought with them advanced learning and skills to Ryukyu, and there is a theory that Chinese kenpō, the origin of karate, was also brought to Ryukyu at this time.

There is also the "Keichōimport theory, "which states that karate was brought to Ryukyu after the invasion of Ryukyu by theSatsuma Domain(Keichō 14, 1609), as well as the theory that it was introduced byKōshōkun(Okinawan: Kūsankū) based on the description inŌshima Writing.[35]

Other theories[edit]

There are also other theories, such as that it developed from Okinawansumo(shima) or that it originated fromjujutsu,which had been introduced from Japan.[36]

Okinawa[edit]

15th–17th centuries[edit]

The reason for the development of unarmed combat techniques in Ryukyu has conventionally been attributed to a policy of banning weapons, which is said to have been implemented on two occasions. The first was during the reign of KingShō Shin(1476–1526; r. 1477–1527), when weapons were collected from all over the country and strictly controlled by the royal government. The second time was after the invasion of Ryukyu by the Satsuma Domain in 1609. Through the two policies, the popular belief that Ryukyuan samurai, who were deprived of their weapons, developed karate to compete with Satsuma's samurai has traditionally been referred to as if it were a historical fact.[37]

However, in recent years, many researchers have questioned the causal relationship between the policy of banning weapons and the development of karate.[38]For example, as the basis for King Shō Shin's policy of banning weapons, an inscription on the parapet of the main hall of Shuri Castle (Trăm phổ thêm lan làm chi minh,1509), which states that "swords, bows and arrows are to be piled up exclusively as weapons of national defense,"[39]has been conventionally interpreted as meaning "weapons were collected and sealed in a warehouse." However, in recent years, researchers of Okinawan studies have pointed out that the correct interpretation is that "swords, bows and arrows were collected and used as weapons of the state."[40]

It is also known that the policy of banning weapons (a 1613 notice to the Ryukyu royal government), which is said to have been implemented by the Satsuma Domain, only prohibited the carrying of swords and other weapons, but not their possession, and was a relatively lax regulation. This notice stated, "(1) The possession of guns is prohibited. (2) The possession of weapons owned privately by princes, three magistrates, and samurai is permitted. (3) Weapons must be repaired in Satsuma through the magistrate's office of Satsuma. (4) Swords must be reported to the magistrate's office of Satsuma for approval."[41]It did not prohibit the possession of weapons (except guns) or even their practice. In fact, even after subjugation to the Satsuma Domain, a number of Ryukyuan masters of swordsmanship, spearmanship, archery, and other arts are known. Therefore, some researchers criticize the theory that karate developed due to the policy of banning weapons as "a rumor on the street with no basis at all."[42]

Karate began as a common fighting system known aste(Okinawan:tī) among the Ryukyuan samurai class. There were few formal styles ofte,but rather many practitioners with their own methods. One surviving example isMotobu Udundī(lit. 'Motobu Palace Hand'), which has been handed down to this day in the Motobu family, one of the branches of the former Ryukyu royal family.[43]In the 16th century, the Ryukyuan history book "Kyūyō"(Cầu dương,established around 1745) mentions thatKyō Ahagon Jikki[ja],a favored retainer of King Shō Shin, used a martial art called "karate" (Tay không,lit. 'empty hand') to smash both legs of an assassin. This karate is thought to refer tote,not today's karate, and Ankō Asato introduces Kyō Ahagon as a "prominent martial artist."[34]

18th century[edit]

However, some believe that Kyō Ahagon's anecdote is a half-legend and that it is unclear whether he was actually atemaster. In the 18th century, the names of NishindaUēkata,GushikawaUēkata,and Chōken Makabe are known as masters ofte.[44]

NishindaUēkataand GushikawaUēkatawere martial artists active during the reign of KingShō Kei(reigned 1713–1751). NishindaUēkatawas good at spear as well aste,and GushikawaUēkatawas also good at wooden sword (swordsmanship).[45]

Chōken Makabe was a man of the late 18th century. His light stature and jumping ability gave him the nickname "MakabeChān-gwā"(lit. 'little fighting cock'), as he was like achān(fighting cock). The ceiling of his house is said to have been marked by his kicking foot.[46]

It is known that in "Ōshima Writing" (1762), written by Yoshihiro Tobe, a Confucian scholar of theTosa Domain,who interviewed Ryukyuan samurai who had drifted to Tosa (present-dayKōchi Prefecture), there is a description of a martial art calledkumiai-jutsu(Tổ hợp thuật) performed byKōshōkun(Okinawan:Kūsankū). It is believed that Kōshōkun may have been a military officer on a mission from Qing that visited Ryukyu in 1756, and some believe that karate originated with Kōshōkun.

In addition, the will (Part I: 1778, Part II: 1783) of Ryukyuan samurai Aka Pēchin Chokushki (1721–1784) mentions the name of a martial art calledkaramutō(からむとう), along with JapaneseJigen-ryūswordsmanship andjujutsu,indicating that Ryukyuan samurai practiced these arts in the 18th century.[47]

In 1609, the JapaneseSatsuma Domaininvaded Ryukyu and Ryukyu became its vassal state, but it continued to pay tribute to the Ming and Qing Dynasties in China. At the time, China had implemented a policy ofsea banand only traded with tributary countries, so the Satsuma Domain wanted Ryukyu to continue its tribute in order to benefit from it.

The envoys of the tribute mission were chosen from among the samurai class of Ryukyu, and they went toFuzhouinFu gian Provinceand stayed there for six months to a year and a half. Government-funded and privately funded foreign students were also sent to study in Beijing or Fuzhou for several years. Some of these envoys and students studied Chinese martial arts in China. The styles of Chinese martial arts they studied are not known for certain, but it is assumed that they studiedFu gian White Craneand other styles from Fu gian Province.

Sōryo Tsūshin (monk Tsūshin), active during the reign of King Shō Kei, was a monk who went to the Qing Dynasty to study Chinese martial arts and was reportedly one of the best martial artists of his time in Ryukyu.[48]

19th and early 20th century[edit]

It is not known when the nametōde(Đường tay,lit. 'Tang hand') first came into use in the Ryukyu Kingdom, but according to Ankō Asato, it was popularized fromKanga Sakugawa(1786–1867), who was nicknamed "Tōde Sakugawa."[34]Sakugawa was a samurai from Shuri who traveled to Qing China to learn Chinese martial arts. The martial arts he mastered were new and different from te. Astōdewas spread by Sakugawa, traditionaltebecame distinguished asOkinawa-te(Hướng 縄 tay,lit. 'Okinawa hand'), and gradually faded away as it merged withtōde.

It is generally believed that today's karate is a result of the synthesis ofte(Okinawa-te) andtōde.Funakoshi writes, "In the early modern era, when China was highly revered, many martial artists traveled to China to practice Chinese kenpo, and added it to the ancient kenpo, the so-called 'Okinawa-te'. After further study, they discarded the disadvantages of both, adopted their advantages, and added more subtlety, and karate was born."[15]

Early styles of karate are often generalized asShuri-te,Naha-te,andTomari-te,named after the three cities from which they emerged.[49]Each area and its teachers had particular kata, techniques, and principles that distinguished their local version oftefrom the others.

Around the 1820s,Matsumura Sōkon(1809–1899) began teachingOkinawa-te.[50]Matsumura was, according to one theory, a student of Sakugawa. Matsumura's style later became the origin of manyShuri-teschools.

Itosu Ankō(1831–1915) studied under Matsumura and Bushi Nagahama ofNaha-te.[51]He created thePin'anforms ( "Heian"in Japanese) which are simplified kata for beginning students. In 1905, Itosu helped to get karate introduced into Okinawa's public schools. These forms were taught to children at the elementary school level. Itosu's influence in karate is broad. The forms he created are common across nearly all styles of karate. His students became some of the most well-known karate masters, includingMotobu Chōyū,Motobu Chōki,Yabu Kentsū,Hanashiro Chōmo,Gichin FunakoshiandKenwa Mabuni.Itosu is sometimes referred to as "the Grandfather of Modern Karate."[52]

In 1881,Higaonna Kanryōreturned from China after years of instruction withRyu Ryu Koand founded what would becomeNaha-te.One of his students was the founder ofGojū-ryū,Chōjun Miyagi.Chōjun Miyagi taught such well-known karateka asSeko Higa(who also trained with Higaonna),Meitoku Yagi,Miyazato Ei'ichi,andSeikichi Toguchi,and for a very brief time near the end of his life, An'ichi Miyagi (a teacher claimed byMorio Higaonna).

In addition to the three earlytestyles of karate a fourth Okinawan influence is that ofUechi Kanbun(1877–1948). At the age of 20 he went toFuzhouin Fu gian Province, China, to escape Japanese military conscription. While there he studied under Shū Shiwa (Chinese:Zhou ZiheChu tử cùng 1874–1926).[53]He was a leading figure of ChineseNanpa Shorin-kenstyle at that time.[54]He later developed his own style ofUechi-ryūkarate based on theSanchin,Seisan,and Sanseiryu kata that he had studied in China.[55]

Japan[edit]

WhenShō Tai,the last king of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, was ordered to move to Tokyo in 1879, he was accompanied by prominent karate masters such asAnkō Asatoand Chōfu Kyan (father ofChōtoku Kyan). It is unknown if they taught karate to the Japanese in Tokyo, although there are records that Kyan taught his son karate.[56]

In 1908, students from the Okinawa Prefectural Middle School gave a karate demonstration atButokudenin Kyoto, which was also witnessed byKanō Jigorō(founder ofjudo).

In May 1922, Gichin Funakoshi (founder ofShotokan) presented pictures of karate on two hanging scrolls at the first Physical Education Exhibition in Tokyo.[57]The following June, Funakoshi was invited to theKodokanto give a karate demonstration in front of Jigoro Kano and other judo experts. This was the beginning of the full-scale introduction of karate in Tokyo.

In November 1922,Motobu Chōki(founder ofMotobu-ryū) participated in a judo versus bo xing match in Kyoto, defeating a foreign boxer. The match was featured in Japan's largest magazine "King[ja],"which had a circulation of about one million at the time, and karate and Motobu's name became instantly known throughout Japan.[4]

In 1922, Funakoshi published the first book on karate,[58]and in 1926 Motobu published the first technical book on kumite.[59]As karate's popularity grew, karate clubs were established one after another in Japanese universities with Funakoshi and Motobu as instructors.[60][61]

In the Showa era (1926–1989), other Okinawan karate masters also came to mainland Japan to teach karate. These includedKenwa Mabuni,Chōjun Miyagi,Kanken Tōyama,andKanbun Uechi.

With the rise ofmilitarismin Japan, some karate masters gradually came to consider the name karate (Đường tay,lit. 'Tanghand') undesirable. The name karate (Tay không,lit. 'empty hand') had already been used byChōmo Hanashiroin Okinawa in 1905,[62]and Funakoshi decided to use this name as well. In addition, the namekaratedō(Đường tay nói,lit. 'the way of the Tang hand'), which was already used by the karate club ofTokyo Imperial University(now the University of Tokyo) in 1929 by adding the suffixdō(Nói,way) to karate,[63]was also used by Funakoshi, who decided to use the namekaratedō(Karate,lit. 'the way of the empty hand') in the same way.[15]

Thedōsuffix implies thatkaratedōis a path to self-knowledge, not just a study of the technical aspects of fighting. Like most martial arts practised in Japan, karate made its transition from -jutsuto -dōaround the beginning of the 20th century. The "dō"in" karate-dō "sets it apart from karate-jutsu,asaikidois distinguished fromaikijutsu,judo fromjujutsu,kendofromkenjutsuandiaidofromiaijutsu.

In 1933, karate was officially recognized as a Japanese martial art by theDai Nippon Butoku Kai,but initially belonged to thejujutsudivision and title examinations were conducted by jujutsu masters.

In 1935, Funakoshi changed the names of many kata and karate itself. Funakoshi's motivation was that the names of many of the traditional kata were unintelligible, and that it would be inappropriate to use the Chinese style names in order to teach karate as a Japanese martial art.[64]He also said that the kata had to be simplified in order to spread karate as a form of physical education, so some of the kata were modified.[65]He always referred to what he taught as simply karate, but in 1936 he built a dōjō in Tokyo and the style he left behind is usually calledShotokanafter this dōjō.Shoto,meaning "pine wave", was Funakoshi's pen name andkanmeaning "hall".

On October 25, 1936, a roundtable meeting of karate masters was held in Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, where it was officially decided to change the name of karate from karate (Tang hand) to karate (empty hand). In attendance were Chōmo Hanashiro, Chōki Motobu, Chōtoku Kyan,Jūhatsu Kyoda,Chōjun Miyagi,Shinpan Gusukuma,andChōshin Chibana.In 2005, theOkinawa Prefectural Assemblypassed a resolution to commemorate this decision by designating October 25 as "Karate Day."[66]

The modernization and systemization of karate in Japan also included the adoption of the white uniform that consisted of thekimonoand thedogiorkeikogi—mostly called justkarategi—and coloured belt ranks. Both of these innovations were originated and popularized byJigoro Kano,the founder of judo and one of the men Funakoshi consulted in his efforts to modernize karate.

At that time, there was almost no kumite training in karate, and kata training was the main focus.[67]There were also no matches. However, at that time, judo andkendomatches were already being held in mainland Japan, andrandori(Loạn lấy り,lit. 'free-style practice')practice was also being actively practiced, the young people in mainland Japan gradually became dissatisfied with kata-only practice.[67]

In pre–World War II Okinawa, karateka practicediri kumi(Okinawanfor kumite) allowing all kinds of techniques (strikes, choke holds, joint locks, etc.) but in a controlled manner to not injure the opponent when aiming to vital areas.[68]Despite sparring was originally an unnoticed form of practice for senior students, there were no "contests" until Western-style competitions were introduced to Japan.[69]

Gichin Funakoshistated, "There are no contests in karate."[70]Shigeru Egamirelates that, during his visit to Okinawa in 1940, he heard some karateka were ousted from theirdōjōbecause they adopted sparring after having learned it in Tokyo. In the early 1930s, pre-arranged sparring was introduced and developed, and finally a few years later free sparring was permitted for Shotokan students.[71]

According toYasuhiro Konishi,kata-only training was often criticized by the leading judo practitioners of the time, such asShuichi NagaokaandHajime Isogai,who said, "The karate you do cannot be understood from kata alone, so why don't you try a little more so that the general public can understand it?"[67]Against the backdrop of these complaints and criticisms, young people such asHironori Ōtsukaand Konishi devised their own kumite and kumite matches, which are the prototypes of today's kumite.[67][72]Motobu's emphasis on kumite attracted Ōtsuka and Konishi, who later studied Okinawan kumite under him.[67]

After World War II, karate activities were temporarily stalled due to the "Notice Banning Judo, Kendo, and Other Martial Arts" issued by the Ministry of Education under the directive of theSupreme Commander for the Allied Powers.However, because this notice did not include the word "karate," it was interpreted by the Ministry of Education that karate was not prohibited, and karate was able to resume its activities earlier than other martial arts.

A new form of karate calledKyokushinwas formally founded in 1957 byMasutatsu Oyama(who was born a Korean, Choi Yeong-Eui 최영의). Kyokushin is largely a synthesis of Shotokan and Gōjū-ryū. It teaches a curriculum that emphasizesaliveness,physical toughness, andfull contactsparring. Because of its emphasis on physical, full-forcesparring,Kyokushin is now often called "full contact karate",or"Knockdown karate"(after the name for its competition rules). Many other karate organizations and styles are descended from the Kyokushin curriculum.

Practice[edit]

Karate can be practiced as an art (budō),self defenseor as acombat sport.Traditional karate places emphasis on self-development (budō).[73]Modern Japanese style training emphasizes the psychological elements incorporated into a properkokoro(attitude) such as perseverance, fearlessness, virtue, and leadership skills. Sport karate places emphasis on exercise and competition. Weapons are an important training activity in some styles of karate.

Karate training is commonly divided intokihon(basics or fundamentals),kata(forms), andkumite(sparring).

Kihon[edit]

Kihon means basics and these form the base for everything else in the style including stances, strikes, punches, kicks and blocks. Karate styles place varying importance on kihon. Typically this is training in unison of a technique or a combination of techniques by a group of karateka. Kihon may also be prearranged drills in smaller groups or in pairs.

Kata[edit]

Kata (Hình:かた) means literally "shape" or "model." Kata is a formalized sequence of movements which represent various offensive and defensive postures. These postures are based on idealized combat applications. The applications when applied in a demonstration with real opponents is referred to as aBunkai.The Bunkai shows how every stance and movement is used. Bunkai is a useful tool to understand a kata.

To attain a formal rank the karateka must demonstrate competent performance of specific required kata for that level. The Japanese terminology for grades or ranks is commonly used. Requirements for examinations vary among schools.

Kumite[edit]

Sparringin Karate is called kumite ( tổ tay:くみて). It literally means "meeting of hands." Kumite is practiced both as a sport and as self-defense training. Levels of physical contact during sparring vary considerably.Full contact karatehas several variants. Knockdown karate (such asKyokushin) uses full power techniques to bring an opponent to the ground. Sparring in armour,bogu kumite,allows full power techniques with some safety. Sport kumite in many international competition under theWorld Karate Federationis free or structured withlight contactorsemi contactand points are awarded by a referee.

In structured kumite (yakusoku,prearranged), two participants perform a choreographed series of techniques with one striking while the other blocks. The form ends with one devastating technique (hito tsuki).

In free sparring (Jiyu Kumite), the two participants have a free choice of scoring techniques. The allowed techniques and contact level are primarily determined by sport or style organization policy, but might be modified according to the age, rank and sex of the participants. Depending upon style,take-downs,sweepsand in some rare cases even time-limitedgrapplingon the ground are also allowed.

Free sparring is performed in a marked or closed area. The bout runs for a fixed time (2 to 3 minutes.) The time can run continuously (iri kume) or be stopped for referee judgment. Inlight contactorsemi contactkumite, points are awarded based on the criteria: good form, sporting attitude, vigorous application, awareness/zanshin,good timing and correct distance. In full contact karate kumite, points are based on the results of the impact, rather than the formal appearance of the scoring technique.

Dōjō Kun[edit]

In thebushidōtraditiondōjō kunis a set of guidelines for karateka to follow. These guidelines apply both in thedōjō(training hall) and in everyday life.

Conditioning[edit]

Okinawan karate uses supplementary training known ashojo undo.This uses simple equipment made of wood and stone. Themakiwarais a striking post. Thenigiri gameis a large jar used for developing grip strength. These supplementary exercises are designed to increasestrength,stamina,speed,andmuscle coordination.[74]Sport Karate emphasizesaerobic exercise,anaerobic exercise,power,agility,flexibility,andstress management.[75]All practices vary depending upon the school and the teacher.

Sport[edit]

Karate is divided into style organizations.[76]These organizations sometimes cooperate in non-style specific sport karate organizations or federations. Examples of sport organizations include AAKF/ITKF, AOK, TKL, AKA, WKF, NWUKO, WUKF and WKC.[77]Organizations hold competitions (tournaments) from local to international level. Tournaments are designed to match members of opposing schools or styles against one another in kata, sparring and weapons demonstration. They are often separated by age, rank and sex with potentially different rules or standards based on these factors. The tournament may be exclusively for members of a particular style (closed) or one in which any martial artist from any style may participate within the rules of the tournament (open).

TheWorld Karate Federation(WKF) is the largest sport karate organization and is recognized by theInternational Olympic Committee(IOC) as being responsible for karate competition in the Olympic Games.[78]The WKF has developed common rules governing all styles. The national WKF organizations coordinate with their respectiveNational Olympic Committees.

WKF karate competition has two disciplines: sparring (kumite) and forms (kata).[79]Competitors may enter either as individuals or as part of a team. Evaluation for kata and kobudō is performed by a panel of judges, whereas sparring is judged by a head referee, usually with assistant referees at the side of the sparring area. Sparring matches are typically divided by weight, age, gender, and experience.[80]

WKF only allows membership through one national organization/federation per country to which clubs may join. The World Union of Karate-do Federations (WUKF)[81]offers different styles and federations a world body they may join, without having to compromise their style or size. The WUKF accepts more than one federation or association per country.

Sport organizations use different competition rule systems.[76][80][82][83][84]Light contactrules are used by the WKF, WUKO, IASK and WKC.Full contact karaterules used byKyokushinkai,Seidokaikanand other organizations.Bogu kumite(full contact with protective shielding of targets) rules are used in the World Koshiki Karate-Do Federation organization.[85]Shinkaratedo Federation use bo xing gloves.[86]Within the United States, rules may be under the jurisdiction of state sports authorities, such as the bo xing commission.

Mixed Martial Arts (MMA)[edit]

Karate, although not widely used inmixed martial arts,has been effective for some MMA practitioners.[87][88]Various styles of karate are practiced in MMA:Lyoto MachidaandJohn MakdessipracticeShotokan;[89]Bas RuttenandGeorges St-Pierretrain inKyokushin;[90]Michelle Watersonholds ablack beltinAmerican Free Style Karate;[91]Stephen ThompsonpracticesAmerican Kenpo Karate;[92]and bothGunnar Nelson[93]andRobert WhittakerpracticedGōjū-ryū.[94]Additionally,John Kavanaghhas been successful as coach with aKenpo Karatepedigree.[95]

Olympic Games[edit]

In August 2016, theInternational Olympic Committeeapprovedkarate as an Olympic sportbeginning at the2020 Summer Olympics.[96][97]Karate also debuted at the2018 Summer Youth Olympics.During this debut of Karate in the Summer Olympics, sixty competitors from around the world competed in the Kumite competition, and twenty competed in the Kata competition. In September 2015, karate was included in a shortlist along withbaseball,softball,skateboarding,surfing,andsport climbingto be considered for inclusion in the 2020 Summer Olympics;[98]and in June 2016, the executive board of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced that they would support the proposal to include all of the shortlisted sports in the 2020 Games.[99]Finally, on 3 August 2016, all five sports (counting baseball and softball together as one sport) were approved for inclusion in the 2020 Olympic program.[100]

Karate will not be included in the2024 Olympic Games,although it has made the shortlist for inclusion, alongside nine others, in the2028 Summer Olympics.[101]

Dan Rank system[edit]

In 1924, Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan Karate, adopted theDansystem from the judo founderJigoro Kano[102]using arank schemewith a limited set of belt colors. Other Okinawan teachers also adopted this practice. In theKyū/Dansystem the beginner grades start with a higher numbered kyū (e.g.,10th Kyū or Jukyū) and progress toward a lower numbered kyū. The Dan progression continues from 1st Dan (Shodan, or 'beginning dan') to the higher dan grades. Kyū-grade karateka are referred to as "color belt" or mudansha ( "ones without dan/rank" ). Dan-grade karateka are referred to asyudansha(holders of dan/rank). Yudansha typically wear ablack belt.Normally, the first five to six dans are given by examination by superior dan holders, while the subsequent (7 and up) are honorary, given for special merits and/or age reached. Requirements of rank differ among styles, organizations, and schools. Kyū ranks stressKarate stances,Equilibrioception,andmotor coordination.Speed and power are added at higher grades.

Minimum age and time in rank are factors affecting promotion. Testing consists of demonstration of techniques before a panel of examiners or senseis. This will vary by school, but testing may include everything learned at that point, or just new information. The demonstration is an application for new rank (shinsa) and may include basics,kata,bunkai,self-defense, routines,tameshiwari(breaking), and kumite (sparring).

Philosophy[edit]

InKarate-Do Kyohan,Funakoshi quoted from theHeart Sutra,which is prominent inShingonBuddhism: "Form is emptiness, emptiness is form itself" (shiki zokuze kū kū zokuze shiki).[103] He interpreted the "kara" of Karate-dō to mean "to purge oneself of selfish and evil thoughts... for only with a clear mind and conscience can the practitioner understand the knowledge which he receives." Funakoshi believed that one should be "inwardly humble and outwardly gentle." Only by behaving humbly can one be open to Karate's many lessons. This is done by listening and being receptive to criticism. He considered courtesy of prime importance. He said that "Karate is properly applied only in those rare situations in which one really must either down another or be downed by him." Funakoshi did not consider it unusual for a devotee to use Karate in a real physical confrontation no more than perhaps once in a lifetime. He stated that Karate practitioners must "never be easily drawn into a fight." It is understood that one blow from a real expert could mean death. It is clear that those who misuse what they have learned bring dishonor upon themselves. He promoted the character trait of personal conviction. In "time of grave public crisis, one must have the courage... to face a million and one opponents." He taught that indecisiveness is a weakness.[104]

Styles[edit]

Karate is divided into many styles, each with their different training methods, focuses, and cultures; though they mainly originate from the historical Okinawan parent styles of Naha-te, Tomari-te and Shuri-te.

However some of the schools' founders have been sceptical with the separation of karate into many styles.Gichin Funakoshisimply stated that there are as many styles as instructors in the world whileKenwa Mabuniexplained that the notion of different variations of karate came from outsiders.[105]During karate popularization in mainland Japan, it was spread the idea that karate was divided into two branches:Shōrin-ryū(derived fromItosu's teachings) andShōrei-ryū(derived fromHigaonna's teachings);[106]butChōjun Miyagibelieved that was just a wrong perception.[107]Mas Oyamawas actively opposed to the idea of the break-down into several karate schools.[108]He believed that making karate acombat sport,as well keeping it as a martial art, could be a possible approach to unify all schools.[109]

In the modern era the major four styles of karate are considered to beGōjū-ryū,Shotokan,Shitō-ryū,andWadō-ryū.[110]These four styles are those recognised by the World Karate Federation for international kata competition.[111]Some widespread styles[112][106]oftenly accepted for kata competition includeKyokushin,Shōrin-ryūorUechi-Ryūamong others.[113][114][111]

World[edit]

Africa[edit]

Karate has grown in popularity in Africa, particularly in South Africa andGhana.[115][116][117]

Americas[edit]

Canada[edit]

Karate began in Canada in the 1930s and 1940s as Japanese people immigrated to the country. Karate was practised quietly without a large amount of organization. During the Second World War, many Japanese-Canadian families were moved to the interior of British Columbia.Masaru Shintani,at the age of 13, began to study Shorin-Ryu karate in the Japanese camp under Kitigawa. In 1956, after 9 years of training with Kitigawa, Shintani travelled to Japan and metHironori Otsuka(Wado Ryu). In 1958, Otsuka invited Shintani to join his organization Wado Kai, and in 1969 he asked Shintani to officially call his style Wado.[118]

In Canada during this same time, karate was also introduced byMasami Tsuruokawho had studied in Japan in the 1940s underTsuyoshi Chitose.[119]In 1954, Tsuruoka initiated the first karate competition in Canada and laid the foundation for theNational Karate Association.[119]

In the late 1950s Shintani moved to Ontario and began teaching karate and judo at the Japanese Cultural Centre in Hamilton. In 1966, he began (with Otsuka's endorsement) the Shintani Wado Kai Karate Federation. During the 1970s Otsuka appointed Shintani the Supreme Instructor of Wado Kai in North America. In 1979, Otsuka publicly promoted Shintani to hachidan (8th dan) and privately gave him a kudan certificate (9th dan), which was revealed by Shintani in 1995. Shintani and Otsuka visited each other in Japan and Canada several times, the last time in 1980 two years prior to Otsuka's death. Shintani died 7 May 2000.[118]

United States[edit]

After World War II, members of theUnited States militarylearned karate in Okinawa or Japan and then opened schools in the US. In 1945,Robert Triasopened the firstdōjōin the United States inPhoenix, Arizona,a Shuri-ryū karatedōjō.[120]In the 1950s,William J. Dometrich,Ed Parker,Cecil T. Patterson,Gordon Doversola,Harold G. Long,Donald Hugh Nagle,George MattsonandPeter Urbanall began instructing in the US.

Tsutomu Ohshimabegan studying karate under Shotokan's founder, Gichin Funakoshi, while a student at Waseda University, beginning in 1948. In 1957, Ohshima received his godan (fifth-degree black belt), the highest rank awarded by Funakoshi. He founded the first university karate club in the United States atCalifornia Institute of Technologyin 1957. In 1959, he founded the Southern California Karate Association (SCKA) which was renamedShotokan Karate of America(SKA) in 1969.

In the 1960s, Anthony Mirakian,Richard Kim,Teruyuki Okazaki,John Pachivas,Allen Steen,Gosei Yamaguchi (son ofGōgen Yamaguchi),Michael G. Fosterand Pat Burleson began teaching martial arts around the country.[121]

In 1961,Hidetaka Nishiyama,a co-founder of theJapan Karate Association(JKA) and student of Gichin Funakoshi, began teaching in the United States. He founded the International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF).Takayuki Mikamiwas sent to New Orleans by the JKA in 1963.

In 1964,Takayuki Kubotarelocated the International Karate Association from Tokyo to California.

Asia[edit]

Korea[edit]

Due to past conflict between Korea and Japan, most notably during theJapanese occupation of Koreain the early 20th century, the influence of karate in Korea is a contentious issue.[122]From 1910 until 1945, Korea was annexed by the Japanese Empire. It was during this time that many of the Korean martial arts masters of the 20th century were exposed to Japanese karate. After regaining independence from Japan, many Korean martial arts schools that opened up in the 1940s and 1950s were founded by masters who had trained in karate in Japan as part of their martial arts training.

Won Kuk Lee,a Korean student of Funakoshi, founded the first martial arts school after the Japanese occupation of Korea ended in 1945, called theChung Do Kwan.Having studied underGichin FunakoshiatChuo University,Lee had incorporatedtaekkyon,kung fu,and karate in the martial art that he taught which he called "Tang Soo Do",the Korean transliteration of the Chinese characters for" Way of Chinese Hand "( đường tay nói ).[123]In the mid-1950s, the martial arts schools were unified under PresidentRhee Syngman's order, and becametaekwondounder the leadership ofChoi Hong Hiand a committee of Korean masters. Choi, a significant figure in taekwondo history, had also studied karate under Funakoshi. Karate also provided an important comparative model for the early founders of taekwondo in the formalization of their art includinghyungand thebelt rankingsystem. The original taekwondohyungwere identical to karatekata.Eventually, original Korean forms were developed by individual schools and associations. Although theWorld Taekwondo FederationandInternational Taekwon-Do Federationare the most prominent among Korean martial arts organizations,tang soo doschools that teach Japanese karate still exist as they were originally conveyed to Won Kuk Lee and his contemporaries from Funakoshi.

Soviet Union[edit]

Karate appeared in the Soviet Union in the mid-1960s, duringNikita Khrushchev's policy of improved international relations. The first Shotokan clubs were opened in Moscow's universities.[124]In 1973, however, the government banned karate—together with all other foreign martial arts—endorsing only the Soviet martial art ofsambo.[125][126]Failing to suppress these uncontrolled groups, the USSR's Sport Committee formed the Karate Federation of USSR in December 1978.[127]On 17 May 1984, the Soviet Karate Federation was disbanded and all karate became illegal again. In 1989, karate practice became legal again, but under strict government regulations, only after thedissolution of the Soviet Unionin 1991 did independent karate schools resume functioning, and so federations were formed and national tournaments in authentic styles began.[128][129]

Philippines[edit]

Europe[edit]

In the 1950s and 1960s, several Japanese karate masters began to teach the art in Europe, but it was not until 1965 that the Japan Karate Association (JKA) sent to Europe four well-trained young Karate instructorsTaiji Kase,Keinosuke Enoeda,Hirokazu KanazawaandHiroshi Shirai.[citation needed]Kase went to France, Enoeada to England and Shirai in Italy. These Masters maintained always a strong link between them, the JKA and the others JKA masters in the world, especiallyHidetaka Nishiyamain the US

France[edit]

France Shotokan Karate was created in 1964 by Tsutomu Ohshima. It is affiliated with another of his organizations, Shotokan Karate of America (SKA). However, in 1965Taiji Kasecame from Japan along with Enoeda and Shirai, who went to England and Italy respectively, and karate came under the influence of the JKA.

Italy[edit]

Hiroshi Shirai,one of the original instructors sent by the JKA to Europe along with Kase, Enoeda and Kanazawa, moved to Italy in 1965 and quickly established a Shotokan enclave that spawned several instructors who in their turn soon spread the style all over the country. By 1970 Shotokan karate was the most spread martial art in Italy apart from Judo. Other styles such asWado Ryu,Goju RyuandShito Ryu,are present and well established in Italy, whileShotokanremains the most popular.

United Kingdom[edit]

Vernon Bell,a 3rd Dan Judo instructor who had been instructed byKenshiro Abbeintroduced Karate to England in 1956, having attended classes inHenry Plée'sYoseikandōjōin Paris. Yoseikan had been founded byMinoru Mochizuki,a master of multiple Japanese martial arts, who had studied Karate withGichin Funakoshi,thus the Yoseikan style was heavily influenced by Shotokan.[130]Bell began teaching in the tennis courts of his parents' back garden in Ilford, Essex and his group was to become the British Karate Federation. On 19 July 1957, Vietnamese Hoang Nam 3rd Dan, billed as "Karate champion of Indo China", was invited to teach by Bell at Maybush Road, but the first instructor from Japan wasTetsuji Murakami(1927–1987) a 3rd Dan Yoseikan under Minoru Mochizuki and 1st Dan of the JKA, who arrived in England in July 1959.[130]In 1959, Frederick Gille set up the Liverpool branch of the British Karate Federation, which was officially recognised in 1961. The Liverpool branch was based at Harold House Jewish Boys Club in Chatham Street before relocating to the YMCA in Everton where it became known as the Red Triangle. One of the early members of this branch wasAndy Sherrywho had previously studied Jujutsu with Jack Britten. In 1961, Edward Ainsworth, another blackbelt Judoka, set up the first Karate study group inAyrshire,Scotland having attended Bell's third 'Karate Summer School' in 1961.[130]

Outside of Bell's organisation, Charles Mack traveled to Japan and studied underMasatoshi Nakayamaof theJapan Karate Associationwho graded Mack to 1st Dan Shotokan on 4 March 1962 in Japan.[130]ShotokaiKarate was introduced to England in 1963 by another ofGichin Funakoshi's students,Mitsusuke Harada.[130]Outside of the Shotokan stable of karate styles,Wado RyuKarate was also an early adopted style in the UK, introduced byTatsuo Suzuki,a 6th Dan at the time in 1964.

Despite the early adoption of Shotokan in the UK, it was not until 1964 that JKA Shotokan officially came to the UK. Bell had been corresponding with the JKA in Tokyo asking for his grades to be ratified in Shotokan having apparently learnt that Murakami was not a designated representative of the JKA. The JKA obliged, and without enforcing a grading on Bell, ratified his black belt on 5 February 1964, though he had to relinquish his Yoseikan grade. Bell requested a visitation from JKA instructors and the next yearTaiji Kase,Hirokazu Kanazawa,Keinosuke EnoedaandHiroshi Shiraigave the first JKA demo at the oldKensington Town Hallon 21 April 1965.Hirokazu KanazawaandKeinosuke Enoedastayed and Murakami left (later re-emerging as a 5th Dan Shotokai under Harada).[130]

In 1966, members of the former British Karate Federation established theKarate Union of Great Britain(KUGB) underHirokazu Kanazawaas chief instructor[131]and affiliated to JKA.Keinosuke Enoedacame to England at the same time as Kanazawa, teaching at adōjōinLiverpool.Kanazawa left the UK after 3 years and Enoeda took over. After Enoeda's death in 2003, the KUGB elected Andy Sherry as Chief Instructor. Shortly after this, a new association split off from KUGB,JKA England. An earlier significant split from the KUGB took place in 1991 when a group led by KUGB senior instructor Steve Cattle formed the English Shotokan Academy (ESA). The aim of this group was to follow the teachings ofTaiji Kase,formerly the JKA chief instructor in Europe, who along with Hiroshi Shirai created the World Shotokan Karate-do Academy (WKSA), in 1989 to pursue the teaching of "Budo" karate as opposed to what he viewed as "sport karate". Kase sought to return the practice of Shotokan Karate to its martial roots, reintroducing amongst other things open hand and throwing techniques that had been side lined as the result of competition rules introduced by the JKA. Both the ESA and the WKSA (renamed the Kase-Ha Shotokan-Ryu Karate-do Academy (KSKA) after Kase's death in 2004) continue following this path today. In 1975, Great Britain became the first team ever to take the World male team title from Japan after being defeated the previous year in the final.

Oceania[edit]

The World Karate Federation was first introduced to Oceania as the Oceania Karate Federation 1973.[132]

Australia[edit]

TheAustralian Karate Federation,under the World Karate Federation, was first introduced in 1970. In 1972 Frank Novak became the first fully qualified Shotokan instructor to arrive in Australia and teach in the country,[133]establishing the first Shotokan Karate dojo in Australia.[134]At karate's debut in the Olympics at the2020 Summer Olympics,Tsuneari Yahirobecame Australia's first Karate Olympian.[135]

In film and popular culture[edit]

Karate spread rapidly in the West through popular culture. In 1950s popular fiction, karate was at times described to readers in near-mythical terms, and it was credible to show Western experts of unarmed combat as unaware of Eastern martial arts of this kind.[136][better source needed]Following theinclusion of judoat the1964 Tokyo Olympics,there was growing mainstream Western interest inJapanese martial arts,particularly karate, during the 1960s.[137]By the 1970s,martial arts films(especiallykung fu filmsandBruce Leeflicksfrom Hong Kong) had formed a mainstream genre and launched the "kung fu craze"which propelled karate and otherAsian martial artsinto mass popularity. However, mainstream Western audiences at the time generally did not distinguish between different Asian martial arts such as karate,kung fuandtae kwon do.[92]

In thefilm series007(1953–present), the mainprotagonistJames Bondis exceptionally skillful in martial arts. He is an expert in various types of martial arts including Karate, as well as Judo, Aikido, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, Filipino Eskrima and Krav Maga.[citation needed]

During the late 20th century, specifically during the80sand90s,karate saw a rise in mainstream popularity. America in the 80s took hold of the martial arts craze and began to produce more homegrown films in themartial arts genre.[138]Films weren't the only popular visual representation of Karate in the 80s, just asarcadesgrew in popularity, so did Karate in arcadefighting games.The first video game to feature fist fighting wasHeavyweight Champin 1976,[139]but it wasKarate Champthat popularized the one-on-one fighting game genre inarcadesin 1984. In 1987,CapcomreleasedStreet Fighter,featuring multiple Karateka characters.[140][141]

The Karate Kid(1984) and its sequelsThe Karate Kid, Part II(1986),The Karate Kid, Part III(1989) andThe Next Karate Kid(1994) are films relating the fictional story of an American adolescent's introduction into karate.[142][143]Its television sequel,Cobra Kai(2018), has led to similar growing interest in karate.[144]The success ofThe Karate Kidfurther popularized karate (as opposed to Asian martial arts more generally) in mainstream American popular culture.[92]Karate Kommandosis an animated children's show, withChuck Norrisappearing to reveal the moral lessons contained in every episode.

Dragon Ball(1984–present) is a Japanesemedia franchise(Anime) whose characters use a variety andhybridofeast Asian martial artsstyles, including Karate[145][146][147]andWing Chun(Kung fu).[146][147][148]Dragon Ballwas originally inspired by the classical 16th-century Chinese novelJourney to the West,combined with elements ofHong Kong martial arts films,with influences ofJackie ChanandBruce Lee.

In the film seriesThe Matrix,Neouses a variety of martial arts styles.[149]Neo's skill in martial arts was shown having downloaded into his brain, which granted combat abilities equivalent to a martial artist with decades of experience. Kenpo Karate is one of the many styles Neo learns as part of his computerised combat training.[150]As part of the preparation for the movie,Yuen Woo-pinghadKeanu Reevesundertake four months of martial arts training in a variety of different styles.[149]

| Practitioner | Fighting style |

|---|---|

| Shin Koyamada | Keishinkan[151] |

| Sonny Chiba | Kyokushin[152] |

| Sean Connery | Kyokushin[153] |

| Hiroyuki Sanada | Kyokushin[154] |

| Dolph Lundgren | Kyokushin[155] |

| Michael Jai White | Kyokushin[156] |

| Yasuaki Kurata | Shito-ryu[157] |

| Fumio Demura | Shitō-ryū[158] |

| Don "The Dragon" Wilson | Gōjū-ryu[159] |

| Richard Norton | Gōjū-ryu[160] |

| Yukari Oshima | Gōjū-ryu[161][162] |

| Leung Siu-Lung | Gōjū-ryu[163] |

| Wesley Snipes | Shotokan[164] |

| Jean-Claude Van Damme | Shotokan[165] |

| Jim Kelly | Shōrin-ryū[166] |

| Joe Lewis | Shōrin-ryū |

| Tadashi Yamashita | Shōrin-ryū[167] |

| Matt Mullins | Shōrei-ryū[168] |

| Sho Kosugi | Shindō jinen-ryū[169] |

| Weng Weng | Undetermined[170] |

Many other film stars such asBruce Lee,Chuck Norris,Jackie Chan,Sammo Hung,andJet Licome from a range of other martial arts.

See also[edit]

- Comparison of karate styles

- Japanese martial arts

- Karate World Championships

- Karate at the Summer Olympics

- Karate at the World Games

References[edit]

- ^abHigaonna, Morio (1985).Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques.p. 17.ISBN0-87040-595-0.

- ^ab"History of Okinawan Karate".2 March 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 2 March 2009.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^Bishop, Mark (1989).Okinawan Karate.A & C Black. pp. 153–166.ISBN0-7136-5666-2.Chapter 9 covers Motobu-ryu and Bugeikan, two 'ti' styles with grappling and vital point striking techniques. Page 165, Seitoku Higa: "Use pressure on vital points, wrist locks, grappling, strikes and kicks in a gentle manner to neutralize an attack."

- ^abMeigenrō, Shujin (1925). "Thịt đạn tương đánh つ đường tay quyền đấu đại thí hợp" [Karate vs. Bo xing, a great match of blows against each other].King(in Japanese). No. September 1925. Dai Nippon Yūben Kōdansha.

- ^Miyagi, Chojun (1993) [1934]. McCarthy, Patrick (ed.).Karate-doh Gaisetsu[An Outline of Karate-Do]. International Ryukyu Karate Research Society. p. 9.ISBN4-900613-05-3.

- ^The name of theTang dynastywas a synonym for "China" in Okinawa.

- ^Draeger & Smith (1969).Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts.Kodansha International. p. 60.ISBN978-0-87011-436-6.

- ^"Here's how US Marines brought karate back home after World War II".We Are The Mighty.2 April 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 2 March 2021.Retrieved11 March2021.

- ^Bishop, Mark (1999).Okinawan Karate Second Edition.Tuttle. p. 11.ISBN978-0-8048-3205-2.

- ^Gary J. Krug (1 November 2001)."Dr. Gary J. Krug: the Feet of the Master: Three Stages in the Appropriation of Okinawan Karate Into Anglo-American Culture".Csc.sagepub. Archived fromthe originalon 17 February 2008.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^Shigeru, Egami (1976).The Heart of Karate-Do.Kodansha International. p. 13.ISBN0-87011-816-1.

- ^Nagamine, Shoshin (1976).Okinawan Karate-do.Tuttle. p. 47.ISBN978-0-8048-2110-0.

- ^"Web Japan"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 13 June 2010.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^ "WKF claims 100 million practitioners".Thekisontheway. Archived fromthe originalon 26 April 2013.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^abcFunakoshi, Gichin (25 May 1935).Karate tài liệu giảng dạy cơ bản[Karatedō Kyōhan] (in Japanese). Tokyo Kōbundō.

- ^"Đường",Wiktionary, the free dictionary,archivedfrom the original on 17 March 2024

- ^Zacharski, Andrzej Jerzy (2019).“Cận đại hướng 縄 tay không の hiện trạng と đầu đề”: Tay không gia たち の mục chỉ す tay không の tinh thần tính["Current State and Issues of Modern Okinawan Karate": Karate Spirituality of the Karate Practitioners] (PhD thesis) (in Japanese). p. 16.hdl:20.500.12000/44338.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (1 October 1956).Karate một đường[Karate-Do My Way] (in Japanese). Sankei Shuppan. p. 55.

- ^Funakoshi, Gishin (1988).Karate-do Nyumon.Japan: Kodansha International. p. 24.ISBN4-7700-1891-6.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2022.Retrieved15 July2010.

- ^Higaonna, Morio (2001).Cương nhu lưu Karate sử: Nhị đại quyền thánh đông ân nạp khoan lượng cung thành trường thuận[Goju-ryu Karate-dō History: The Two Great Masters, Kanryō Higaonna and Chōjun Miyagi] (in Japanese). CHAMP. p. 133.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (1922).Lưu Cầu quyền pháp đường tay[Ryūkyū Kenpō Karate] (in Japanese). Bukyōsha. p. 20.Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2023.Retrieved31 December2023.

- ^Motobu, Chōki (1926).Hướng 縄 quyền pháp đường giải phẫu tổ tay biên[Okinawa Kenpō Karate-jutsu Kumite Edition] (in Japanese). Karate-jutsu Promotion Association. p. 2.

- ^Mifune, Kyuzo (1958).Nói と thuật: Nhu đạo giáo điển[The Way and the Art: A Dictionary of Judo] (in Japanese). Seibundo Shinkosha. p. 5.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2024.Retrieved14 March2024.

- ^Nakasone, Genwa, ed. (1938).Karate đại quan[A Comprehensive View of Karate-dō] (in Japanese). Tokyo Tosho. p. 64.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (1922).Lưu Cầu quyền pháp đường tay[Ryūkyū Kenpō Karate] (in Japanese). Bukyōsha. p. 2.Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2023.Retrieved31 December2023.

- ^Motobu, Chōki (1926).Hướng 縄 quyền pháp đường giải phẫu tổ tay biên[Okinawa Kenpō Karate-jutsu Kumite Edition] (in Japanese). Karate-jutsu Promotion Association. p. 4.

- ^"What's In A Name?".Newpaltzkarate. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2004.Retrieved5 March2015.

- ^"Tay không toạ đàm sẽ" [Karate Roundtable].Ryukyu Shimpo(in Japanese). 27 October 1936.

- ^"Mùa の đề tài: 10 nguyệt 25 ngày tay không の ngày"[Season's Topics: October 25 Karate Day] (in Japanese). Okinawa Prefectural Archives.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2024.Retrieved3 January2024.

- ^Miki, Jisaburo; Takada, Mizuho (1930).Quyền pháp khái nói[Outline of Kenpo] (in Japanese). Todai Karate Kenkyukai. p. 221.

- ^Mifune, Kyuzo (1958).Nói と thuật: Nhu đạo giáo điển[The Way and the Art: A Dictionary of Judo] (in Japanese). Seibundo Shinkosha. p. 6.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2024.Retrieved14 March2024.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (1 October 1956).Karate một đường[Karate-Do My Way] (in Japanese). Sankei Shuppan. p. 56.

- ^Ōyama, Masutatsu (1980).わがカラテ ngày 々 nghiên toản[My Karate Studies Everyday] (in Japanese). Kodansha. p. 232.

- ^abcAsato, Ankō; Funakoshi, Gichin (17 January 1914). "Hướng 縄 の võ kỹ" [Martial Arts of Okinawa] (in Japanese). Ryukyu Shimpo.

- ^Miyagi, Chojun (1934).Đường tay nói khái nói[Overview of Karate-dō] (in Japanese). Ryukyu Karate-jutsu International Research Association.

- ^Shimakura, Ryuji; Majikina Anko (1923).Hướng 縄 một ngàn năm sử[A Thousand Year History of Okinawa] (in Japanese). Nihon University. p. 353.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (1922).Lưu Cầu quyền pháp đường tay[Ryūkyū Kenpō Karate] (in Japanese). Bukyōsha. pp. 21, 22.Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2023.Retrieved31 December2023.

- ^Kinjo, Hiroshi (2011).Đường tay から tay không へ[From Karate to Karate]. Nippon Budokan. pp. 139, 140.ISBN978-4583104294.

- ^The original text is in Chinese, "Chuyên tích đao kiếm cung tiễn cho rằng hộ quốc chi vũ khí sắc bén."

- ^Uezato, Takashi (October 2002)."Cổ Lưu Cầu の quân đội とそ の lịch sử triển khai"[Old Ryukyuan Military and Its Historical Development].Ryukyu Asiatic Studies of Society and Culture(in Japanese) (5): 105–128.Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2023.Retrieved31 December2023.

- ^Kagoshima Prefecture Restoration History Materials Compilation Office, ed. (1984).Lộc nhi đảo huyện tư liệu lịch sử cũ nhớ tạp lục sau biên 4[Kagoshima Prefecture Historical Records, Miscellaneous Old Records, Part 2, 4](PDF)(in Japanese). Kagoshima Prefecture. p. 414.Archived(PDF)from the original on 31 December 2023.Retrieved31 December2023.

- ^Gima, Shinkin; Fujiwara, Ryozo (1 October 1986).Đối nói cận đại Karate の lịch sử を ngữ る[Dialogue: The History of Modern Karate-do] (in Japanese). Baseball Magazine Sha. p. 42.ISBN9784583026060.

- ^Bishop, Mark (1989).Okinawan Karate.A & C Black. p. 154.ISBN0-7136-5666-2.

- ^Motobu, Choki (2020) [1932]. Quast, Andreas (ed.).Watashi no Karatejutsu[My Art and Skill of Karate]. Translated by Quast, Andreas; Motobu, Naoki. Independently Published. p. 165.ISBN9798601364751.

- ^Motobu, Choki (2020) [1932]. Quast, Andreas (ed.).Watashi no Karatejutsu[My Art and Skill of Karate]. Translated by Quast, Andreas; Motobu, Naoki. Independently Published. p. 153.ISBN9798601364751.

- ^Motobu, Chōki (1932).Tư の đường giải phẫu[My karate Art] (in Japanese). Tokyo Karate Promotion Association. p. 83.

- ^Higashionna, Kanjun (1978). Ryukyu Shimpo (ed.).Đông ân nạp khoan đôn toàn tập[The Complete Works of Kanjun Higashionna] (in Japanese). Vol. 5. Daiichi Shobo. p. 410.

- ^Motobu, Chōki (1932).Tư の đường giải phẫu[My karate Art] (in Japanese). Tokyo Karate Promotion Association. p. 82.

- ^Higaonna, Morio (1985).Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques.p. 19.ISBN0-87040-595-0.

- ^Yoshimura, Jinsai (1941). "Tự vân võ đạo nhớ" [Biography of Martial Arts].Monthly Bunka Okinawa.Vol. 2–8, September. Gekkan Bunka Okinawa-sha. p. 22.

- ^Motobu, Choki (2020) [1932]. Quast, Andreas (ed.).Watashi no Karatejutsu[My Art and Skill of Karate]. Translated by Quast, Andreas; Motobu, Naoki. Independently Published. p. 36.ISBN9798601364751.

- ^International Ryukyu Karate-jutsu Research Society (15 October 2012)."Patrick McCarthy, footnote #4".Archived fromthe originalon 30 January 2014.Retrieved23 May2014.

- ^Fujimoto, Keisuke (2017).The Untold Story of Kanbun Uechi.pp. 19.

- ^"Kanbun Uechi history".1 March 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 1 March 2009.Retrieved23 May2014.

- ^Hokama, Tetsuhiro (2005).100 Masters of Okinawan Karate.Ozata Print. p. 28.

- ^Shō, Kyū (1915).廃 phiên lúc ấy の nhân vật[Persons at the Time of the Abolition of the Domain] (in Japanese). Shō Kyū. p. 72.doi:10.11501/933701.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2023.Retrieved19 December2023.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (1 October 1956).Karate một đường[Karate-Do My Way] (in Japanese). Sankei Shuppan. p. 109.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (1922).Lưu Cầu quyền pháp đường tay[Ryūkyū Kenpō Karate] (in Japanese). Bukyōsha.

- ^Motobu, Chōki (1926).Hướng 縄 quyền pháp đường giải phẫu: Tổ tay biên[Okinawa Kenpō Karate-jutsu: Kumite Edition] (in Japanese). Karate-jutsu Promotion Association.

- ^Tay không nghiên cứu xã (1934). Karate Kenkyusha (ed.).Tay không nghiên cứu[Karate Studies] (in Japanese). Kōbukan. p. 75.doi:10.11501/1027727.

- ^Khánh ứng nghĩa thục thể dục sẽ tay không bộ (1936). Keio University Physical Education Association Karate Club (ed.).Karate tổng thể[Karate-do Shusei] (in Japanese). Vol. 1. Keio University Physical Education Association Karate Club. p. 25.doi:10.11501/1144879.

- ^Trọng tông căn, nguyên cùng, 1895-1978 (1938). Nakasone, Genwa (ed.).Karate đại quan[Karate-dō Taikan] (in Japanese). Tokyo Tosho. p. 64.doi:10.11501/1104139.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Miki, Jisaburō; Takada, Mizuho (1930).Quyền pháp khái nói[Introduction to Kenpō] (in Japanese). Karate Research Association of Tokyo Imperial University. p. 221.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (25 May 1935).Karate tài liệu giảng dạy cơ bản[Karatedō Kyōhan] (in Japanese). Tokyo Kōbundō. p. 33.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin (1 October 1956).Karate một đường[Karate-Do My Way] (in Japanese). Sankei Shuppan. p. 57.

- ^"The declaration of the" Karate Day "".Okinawa Karate Information Center. 8 September 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2023.Retrieved19 December2023.

- ^abcde"Đối nói ・ゲスト tiểu tây khang dụ / nghe き tay trì điền phụng tú ・ Karate を ngữ る: Qua đi と hiện tại の võ đạo coi điểm" [Dialogue, Guest: Yasuhiro Konishi / Interviewer: Fusuhide Ikeda, Talking about Karate-do: Budo perspectives of the past and present].Dialogue Collection: Talking about Karate-do(in Japanese). Budo Publishing Research Institute. 1977. pp. 5–7.

- ^Higaonna, Morio (1990).Traditional Karatedo Vol. 4 Applications of the Kata.Minato Research. p. 135.ISBN9780870408489.

- ^Shigeru, Egami (1976).The Heart of Karatedo.Kodansha International. p. 111.ISBN0870118161.

- ^Shigeru, Egami (1976).The Heart of Karatedo.Kodansha International. p. 111.ISBN0870118161.

- ^Shigeru, Egami (1976).The Heart of Karatedo.Kodansha International. p. 113.ISBN0870118161.

- ^"Karate を ngữ る/ đại trủng bác kỷ ( そ の 1 )" [Talking about Karate-do/Hironori Ōtsuka (Part 1)].Monthly Budo Shūdan(in Japanese). Vol. 12, no. 1. Budo Publishing Research Institute. 1978. p. 13.

- ^"International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF)".Archived fromthe originalon 4 December 2010.Retrieved23 May2014.

- ^Higaonna, Morio (1985).Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques.p. 67.ISBN0-87040-595-0.

- ^Mitchell, David (1991).Winning Karate Competition.A & C Black. p. 25.ISBN0-7136-3402-2.

- ^abGoldstein, Gary (May 1982)."Tom Lapuppet, Views of a Champion".Black Belt Magazine.Active Interest Media.p. 62.Retrieved13 October2015.

- ^"World Karate Confederation".Wkc-org.net.Archivedfrom the original on 19 May 2010.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^"Activity Report"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 7 November 2011.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^"The Global Allure of Karate".2 January 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2019.Retrieved20 March2018.

- ^abWarnock, Eleanor (25 September 2015)."Which Kind of Karate Has Olympic Chops?".WSJ.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2022.Retrieved18 October2015.

- ^"WUKF – World Union of Karate-Do Federations".Wukf-karate.org.Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2013.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^"Black Belt".September 1992. p. 31.Retrieved10 October2015.

- ^Joel Alswang (2003).The South African Dictionary of Sport.New Africa Books. p. 163.ISBN9780864865359.Retrieved10 October2015.

- ^Adam Gibson; Bill Wallace (2004).Competitive Karate.Human Kinetics.ISBN9780736044929.Retrieved10 October2015.

- ^"World Koshiki Karatedo Federation".Koshiki.org.Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2010.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^"Shinkaratedo Renmei".Shinkarate.net.Archivedfrom the original on 12 June 2010.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^"Technique Talk: Stephen Thompson Retrofits Karate for MMA".MMA Fighting. 18 February 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2014.Retrieved23 May2014.

- ^"Lyoto Machida and the Revenge of Karate".Sherdog.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2010.Retrieved13 February2010.

- ^Lead MMA Analyst (14 February 2014)."Lyoto Machida: Old-School Karate".Bleacher Report.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2014.Retrieved23 May2014.

- ^Wickert, Marc."Montreal's MMA Warrior".Knucklepit.Archived fromthe originalon 13 June 2007.Retrieved6 July2007.

- ^"Who is Michelle Waterson?".mmamicks. 8 June 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2017.Retrieved16 March2017.

- ^abcSchneiderman, R. M. (23 May 2009)."Contender Shores Up Karate's Reputation Among U.F.C. Fans".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2013.Retrieved30 January2010.

- ^Dan Shapiro (17 July 2014)."Gunnar Nelson in the Style of Iceland".Vice Fightland Blog. Archived fromthe originalon 14 February 2020.

- ^"5 Things You Might Not Know About Robert Whitakker".sherdog. 8 February 2019.

- ^Kavanagh, John (2016).Win or Learn.Penguin. p. 6.

- ^"IOC approves five new sports for Olympic Games Tokyo 2020".IOC.Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2020.Retrieved4 August2016.

- ^"Olympics: Baseball/softball, sport climbing, surfing, karate, skateboarding at Tokyo 2020".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 5 June 2021.Retrieved4 August2016.

- ^"Surfing and skateboarding make shortlist for 2020 Olympics".GrindTV.28 September 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 13 August 2016.Retrieved8 August2016.

- ^"IOC Executive Board supports Tokyo 2020 package of new sports for IOC Session – Olympic News".Olympic.org. 1 June 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2020.Retrieved8 August2016.

- ^"IOC approves five new sports for Olympic Games Tokyo 2020".olympics.org International Olympic Committee. 3 August 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2020.Retrieved22 August2016.

- ^"Motorsport, cricket and karate among nine sports on shortlist for Los Angeles 2028 inclusion".Inside the Games. 3 August 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2022.Retrieved4 August2022.

- ^Hokama, Tetsuhiro (2005).100 Masters of Okinawan Karate.Okinawa: Ozata Print. p. 20.

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin. "Karate-dō Kyohan – The Master Text" Tokyo. Kodansha International; 1973. Page 4

- ^Funakoshi, Gichin. "Karate-dō Kyohan – The Master Text" Tokyo. Kodansha International; 1973.

- ^Ōyama, Masutatsu (1984) [1965]."21. Schools and Formal Exercises".This is Karate!(4th ed.). Japan Publications. p. 315.ISBN0-87040-254-4.

- ^abPruim, Andy (June 1990).A Karate Compendium: A History of Karate from Te to Z in Black Belt Magazine.Active Interest Media, Inc. pp. 18–19.Retrieved31 May2022.

- ^"The meeting that changed Karate history forever".Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2024.Retrieved2 May2024.

- ^Ōyama, Masutatsu (1974) [1958]."11. New Directions in Karate".What is Karate?(8th ed.). Japan Publications. p. 168-169.ISBN0-87040-147-5.

- ^Ōyama, Masutatsu (1984) [1965]."25. Karate Future's Progress".This is Karate!(4th ed.). Japan Publications. p. 327-328.ISBN0-87040-254-4.

- ^Mishra, Tamanna (2020)."Chapter-1.1 Basic Karate".Karate Kudos.Notion Press.ISBN9781648288166.

- ^abLund, Graeme (2015).The Essential Karate Book.Tuttle. p. 6.ISBN9781462905591.

- ^"All Karate Styles and Their Differences".Way of Martial Arts.3 May 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 5 July 2022.Retrieved31 May2022.

- ^"WUKF Rules".World Union of Karate-do Federations.Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2024.Retrieved4 May2024.

- ^"Documents".World Karate Martial Arts Organization.Archivedfrom the original on 10 December 2023.Retrieved4 May2024.

- ^"National Sports Authority, Ghana".Sportsauthority.gh. Archived fromthe originalon 2 April 2015.Retrieved5 March2015.

- ^Resnekov, Liam (16 July 2014)."Love and Rebellion: How Two Karatekas Fought Apartheid".Fightland.vice.Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2019.Retrieved5 March2015.

- ^Aggrey, Joe (6 May 1997)."Graphic Sports: Issue 624 May 6–12 1997".Graphic Communications Group.Retrieved22 August2017– via Google Books.

- ^abRobert, T. (2006)."no title given".Journal of Asian Martial Arts.15(4). this issue is not available as a back issue.[dead link]

- ^ab"Karate".The Canadian Encyclopedia – Historica-Dominion. 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 29 August 2014.Retrieved20 July2010.

- ^Harty, Sensei Thomas."About Grandmaster Robert Trias".suncoastkarate.Archivedfrom the original on 29 May 2018.Retrieved13 February2018.

- ^The Original Martial Arts Encyclopedia,John Corcoranand Emil Farkas, pgs. 170–197

- ^Orr, Monty; Amae, Yoshihisa (December 2016)."Karate in Taiwan and South Korea: A Tale of Two Postcolonial Societies"(PDF).Taiwan in Comparative Perspective.6.Taiwan Research Programme, London School of Economics: 1–16.ISSN1752-7732.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 11 August 2017.Retrieved24 July2017.

- ^"Academy".Tangsudo. 18 October 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2014.Retrieved5 March2015.

- ^"Black Belt".Active Interest Media, Inc. 1 June 1979.Retrieved3 January2018– via Google Books.

- ^Risch, William Jay (17 December 2014).Youth and Rock in the Soviet Bloc: Youth Cultures, Music, and the State in Russia and Eastern Europe.Le xing ton Books.ISBN9780739178232.Retrieved3 January2018– via Google Books.

- ^Hoberman, John M. (30 June 2014).Sport and Political Ideology.University of Texas Press.ISBN9780292768871.Retrieved3 January2018– via Google Books.

- ^"Black Belt".Active Interest Media, Inc. 1 July 1979.Retrieved3 January2018– via Google Books.

- ^Volkov, Vadim (4 February 2016).Violent Entrepreneurs: The Use of Force in the Making of Russian Capitalism.Cornell University Press.ISBN9781501703287.Retrieved3 January2018– via Google Books.

- ^Tomlinson, Alan; Young, Christopher; Holt, Richard (17 June 2013).Sport and the Transformation of Modern Europe: States, Media and Markets 1950-2010.Routledge.ISBN9781136660528.Retrieved3 January2018– via Google Books.

- ^abcdef"Exclusive: UK Karate History".Bushinkai. Archived fromthe originalon 23 February 2014.

- ^"International Association of Shotokan Karate (IASK)".Karate-iask. Archived fromthe originalon 29 May 2013.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^"History – OKF".Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2023.Retrieved21 May2023.

- ^Competition, Filed under; General; JKA; Shotokan; Traditional (16 August 2020)."Frank Nowak".Finding Karate.Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2023.Retrieved21 May2023.

- ^"Shotokan Karate International Australia (SKIA Vic) – Karate Victoria".karatevictoria.au.Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2023.Retrieved21 May2023.

- ^""Olympic Destiny" as Tsuneari Yahiro Announced as Australia's First Karate Olympian ".Australian Olympic Committee.24 June 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 13 May 2023.Retrieved21 May2023.

- ^For example,Ian Fleming's bookGoldfinger(1959, p.91–95) describes the protagonistJames Bond,an expert in unarmed combat, as utterly ignorant of Karate and its demonstrations, and describes the Korean 'Oddjob' in these terms:Goldfinger said, "Have you ever heard of Karate? No? Well that man is one of the three in the world who have achieved theBlack Beltin Karate. Karate is a branch of judo, but it is to judo what aspandauis to acatapult... ".Such a description in a popular novel assumed and relied upon Karate being almost unknown in the West.

- ^Polly, Matthew (2019).Bruce Lee: A Life.Simon and Schuster.p. 145.ISBN978-1-5011-8763-6.

- ^Francis, Anthony (7 October 2020)."10 Best Martial Arts Movies Of The 80s, Ranked".ScreenRant.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2023.Retrieved7 May2023.

- ^"Heavyweight Champ".Ultimate History of Video games.Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2019.Retrieved8 October2017.

- ^All About Capcom Head-to-Head Fighting Game 1987–2000,pg. 320

- ^"キャラクター giới thiệu".Archived fromthe originalon 5 December 1998.Retrieved7 May2023.

- ^"The Karate Generation".Newsweek.18 February 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 15 May 2009.Retrieved18 February2010.

- ^"Jaden Smith Shines in The Karate Kid".Newsweek.10 June 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 16 October 2010.Retrieved13 October2010.

- ^"Local dojo experiencing business boon after 'Cobra Kai'".KRIS.11 January 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2021.Retrieved9 April2021.

- ^"The Martial Arts of Dragon Ball Z".nkkf.org.Archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2023.Retrieved27 May2023.

- ^abArts, Way of Martial."What Martial Arts Does Goku Use? (Do They Work In Real Life?)".Archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2023.Retrieved27 May2023.

- ^abGerardo (19 April 2021)."What Martial Arts Does Goku Use in Dragon Ball Z?".Combat Museum.Archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2023.Retrieved27 May2023.

- ^"Dragon Ball: 10 Fictional Fighting Styles That Are Actually Based On Real Ones".CBR.5 May 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2023.Retrieved27 May2023.

- ^abHutton, Robert (2 July 2022)."Every Martial Arts Style Neo Uses In The Matrix (Not Just Kung Fu)".ScreenRant.Retrieved13 May2023.

- ^"Martial Matrix:: WINM:: Keanu Reeves Articles & Interviews Archive".whoaisnotme.net.Archivedfrom the original on 13 May 2023.Retrieved13 May2023.

- ^"Shin Koyamada's Inaugural 2nd Annual United States Martial Arts Festival".Independent.1 November 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 25 March 2023.Retrieved25 March2023.

- ^"International Karate Organization KYOKUSHINKAIKAN Domestic Black Belt List As of Oct.2000".Kyokushin Karate Sōkan: Shin Seishin Shugi Eno Sōseiki E.Aikēōshuppanjigyōkyoku: 62–64. 2001.ISBN4-8164-1250-6.

- ^Rogers, Ron."Hanshi's Corner 1106"(PDF).Midori Yama Budokai.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 18 January 2012.Retrieved20 August2011.

- ^Hiroyuki Sanada: "Promises" for Peace Through Film.Ezine.kungfumagazine.Kung Fu Magazine,Retrieved on 21 November 2011.Archived12 November 2013 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Celebrity Fitness—Dolph Lundgren".Inside Kung Fu.Archived fromthe originalon 29 November 2010.Retrieved15 November2010.

- ^"Talking With…Michael Jai White".GiantLife.Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2010.Retrieved16 June2010.

- ^"Yasuaki Kurata Filmography".Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2017.Retrieved17 May2017.

- ^[1]Archived28 September 2009 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Martial Arts Legend".n.d. Archived fromthe originalon 29 September 2013.Retrieved29 July2013.

- ^Black Belt Magazine March, 1994, p. 24.March 1994.Retrieved14 March2013.

- ^"Goju-ryu".n.d.Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2014.Retrieved24 June2013.

- ^"Yukari Oshima's Biography".Archived fromthe originalon 28 August 2012.Retrieved24 June2013.

- ^"Goju-ryu".n.d. Archived fromthe originalon 3 September 2015.Retrieved26 May2014.

- ^"Wesley Snipes: Action man courts a new beginning".Independent.London. 4 June 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 7 June 2010.Retrieved10 June2010.

- ^"Why is he famous?".ASK MEN.Archived fromthe originalon 9 April 2010.Retrieved15 June2010.

- ^"Martial arts biography – jim kelly".Archived fromthe originalon 29 August 2013.Retrieved21 August2013.