Kosovo

Republic of Kosovo | |

|---|---|

| Anthem:Himni i Republikës së Kosovës "Anthem of the Republic of Kosovo" | |

Location of Kosovo (green) | |

| Status | |

| Capital and largest city | Pristinaa 42°40′N21°10′E/ 42.667°N 21.167°E |

| Official languages | Albanian Serbian[2] |

| Regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2019)[4] | |

| Religion (2020)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Vjosa Osmani | |

| Albin Kurti | |

| Glauk Konjufca | |

| Legislature | Assembly |

| Establishment | |

| 1455 | |

| 1877 | |

| 1913 | |

| 31 January 1946 | |

| 2 July 1990 | |

| 9 June 1999 | |

| 10 June 1999 | |

| 17 February 2008 | |

| 10 September 2012 | |

| 19 April 2013 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,887[6]km2(4,203 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 1.0[7] |

| Population | |

• 2024 census | |

• Density | 146/km2(378.1/sq mi) |

| GDP(PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP(nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini(2017) | low inequality |

| HDI(2021) | high |

| Currency | Euro(€)b(EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +383 |

| ISO 3166 code | XK |

| Internet TLD | .xkc(proposed) |

| |

Kosovo,[a]officially theRepublic of Kosovo,[b]is alandlocked countryinSoutheast Europewithpartial diplomatic recognition.It is bordered byAlbaniato the southwest,Montenegroto the west,Serbiato the north and east andNorth Macedoniato the southeast. It covers an area of 10,887 km2(4,203 sq mi) and a population of approximately 1.6 million. Kosovo has a varied terrain, with high plains along with rolling hills andmountains,some of which reach an altitude of over 2,500 m (8,200 ft). Its climate is mainlycontinentalwith someMediterraneanandalpineinfluences.[17]Kosovo's capital and themost populous cityisPristina;other major cities andurban areasincludePrizren,Ferizaj,GjilanandPeja.[18]

TheDardanitribe emerged in Kosovo and established theKingdom of Dardaniain the 4th century BC. It was later annexed by theRoman Empirein the 1st century BC. The territory remained in theByzantine Empire,facing Slavic migrations from the 6th-7th century AD. Control shifted between the Byzantines and theFirst Bulgarian Empire.In the 13th century, Kosovo became integral to theSerbian medieval stateand the seat of theSerbian Orthodox Church.Ottoman expansionin the Balkans in the late 14th and 15th century led to the decline andfall of the Serbian Empire;theBattle of Kosovoof 1389 is considered to be one of the defining moments, where a Serbian-led coalition consisting of various ethnicities fought against the Ottoman Empire.

Various dynasties, mainly theBranković,would govern Kosovo for a significant portion of the period following the battle. TheOttoman Empirefully conquered Kosovo after theSecond Battle of Kosovo,ruling for nearly five centuries until 1912. Kosovo was the center of theAlbanian Renaissanceand experienced theAlbanian revolts of 1910and1912.After theBalkan Wars(1912–1913), it was ceded to theKingdom of Serbiaand following World War II, it became anAutonomous ProvincewithinYugoslavia.Tensions between Kosovo's Albanian andSerbcommunities simmered through the 20th century and occasionally erupted into major violence, culminating in theKosovo Warof 1998 and 1999, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Yugoslav army and the establishment of theUnited Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo.

Kosovounilaterallydeclared its independencefromSerbiaon 17 February 2008,[19]and has since gained diplomatic recognition as asovereign stateby104 member statesof theUnited Nations.Although Serbia does not officially recognise Kosovo as a sovereign state and continues to claim it as its constituentAutonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija,it accepts the governing authority of the Kosovo institutions as a part of the2013 Brussels Agreement.[20]

Kosovo is a developing country, with anupper-middle-income economy.It has experienced solideconomic growthover the last decade as measured by international financial institutions since the onset of thefinancial crisis of 2007–2008.Kosovo is a member of theInternational Monetary Fund,World Bank,EBRD,Venice Commission,theInternational Olympic Committee,and has applied for membership in theCouncil of Europe,UNESCO,Interpol,and for observer status in theOrganisation of Islamic Cooperation.In December 2022, Kosovo fileda formal applicationto become a member of theEuropean Union.[21]

Etymology

The nameKosovois of South Slavic origin.Kosovo(Serbian Cyrillic:Косово) is the Serbian neuter possessive adjective ofkos(кос), 'blackbird',[22][23]anellipsisforKosovo Polje,'Blackbird Field', the name ofa karst fieldsituated in the eastern half of today's Kosovo and the site of the 1389Battle of Kosovo Field.[24]The name of the karst field was for the first time applied to a wider area when theOttoman Vilayet of Kosovowas created in 1877.

The entire territory that corresponds to today's country is commonly referred to in English simply asKosovoand inAlbanianasKosova(definite form) orKosovë(indefinite form,pronounced[kɔˈsɔvə]). In Serbia, a formal distinction is made between the eastern and western areas of the country; the termKosovo(Косово) is used for the eastern part of Kosovo centred on the historicalKosovo Field,while the western part of the territory of Kosovo is calledMetohija(Albanian:Dukagjin). Thus, in Serbian the entire area of Kosovo is referred to asKosovo and Metohija.[25]

Dukagjini or Dukagjini plateau (Albanian: 'Rrafshi i Dukagjinit') is an alternative name for Western Kosovo, having been in use since the 15th-16th century as part of theSanjakofDukakinwith its capitalPeja,and is named after the medieval AlbanianDukagjini family.[26]

Modern usage

Some Albanians also prefer to refer to Kosovo asDardania,the name of an ancient kingdom and laterRoman province,which covered the territory of modern-day Kosovo. The name is derived from the ancient tribe of theDardani,which is considered be related to the Proto-Albanian termdardā,which means "pear" (Modern Albanian:dardhë).[24][27]The former Kosovo PresidentIbrahim Rugovahad been an enthusiastic backer of a "Dardanian" identity, and the Kosovar presidential flag and seal refer to this national identity. However, the name "Kosova" remains more widely used among the Albanian population. The flag of Dardania remains in use as the officialPresidential seal and standardand is heavily featured in the institution of the presidency of the country.

The official conventional long name, as defined by theconstitution,isRepublic of Kosovo.[28]Additionally, as a result of anarrangement agreed between Pristina and Belgradein talks mediated by the European Union, Kosovo has participated in some international forums and organisations under the title "Kosovo*" with a footnote stating, "This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSC 1244 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence". This arrangement, which has been dubbed the "asterisk agreement", was agreed in an 11-point arrangement on 24 February 2012.[29]

History

Ancient history

The strategic position including the abundant natural resources were favorable for the development of human settlements in Kosovo, as is highlighted by the hundreds of archaeological sites identified throughout its territory.[30]

Since 2000, the increase in archaeological expeditions has revealed many, previously unknown sites. The earliest documented traces in Kosovo are associated to theStone Age;namely, indications that cave dwellings might have existed, such as Radivojce Cave near the source of theDrin River,Grnčar Cave inViti municipalityand the Dema and Karamakaz Caves in themunicipality of Peja.

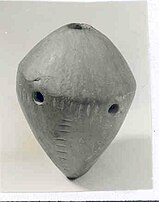

The earliest archaeological evidence of organised settlement, which have been found in Kosovo, belong to theNeolithicStarčevoandVinčacultures.[31]VlashnjëandRunikare important sites of theNeolithic erawith the rock art paintings at Mrrizi i Kobajës nearVlashnjëbeing the first find of prehistoric art in Kosovo.[32]Amongst the finds of excavations in Neolithic Runik is a baked-clayocarina,which is the first musical instrument recorded in Kosovo.[31]

The first archaeological expedition in Kosovo was organised by the Austro-Hungarian army during theWorld War Iin theIllyriantumuliburial grounds of Nepërbishti within thedistrict of Prizren.[30]

The beginning of theBronze Agecoincides with the presence oftumuliburial grounds in western Kosovo, like the site ofRomajë.[30]

TheDardaniwere the most importantPaleo-Balkantribe in the region of Kosovo. A wide area which consists of Kosovo, parts of Northern Macedonia and eastern Serbia was namedDardaniaafter them in classical antiquity, reaching to theThraco-Illyriancontact zone in the east. In archaeological research, Illyrian names are predominant in western Dardania, while Thracian names are mostly found in eastern Dardania.

Thracian names are absent in western Dardania, while some Illyrian names appear in the eastern parts. Thus, their identification as either anIllyrianorThraciantribe has been a subject of debate, the ethnolinguistic relationship between the two groups being largely uncertain and debated itself as well. The correspondence of Illyrian names, including those of the ruling elite, in Dardania with those of the southern Illyrians suggests a thracianization of parts of Dardania.[33]The Dardani retained an individuality and continued to maintain social independence after Roman conquest, playing an important role in the formation of new groupings in the Roman era.[34]

Roman period

During Roman rule, Kosovo was part of two provinces, with its western part being part ofPraevalitana,and the vast majority of its modern territory belonging toDardania.Praevalitana and the rest of Illyria was conquered by theRoman Republicin 168 BC. On the other hand, Dardania maintained its independence until the year 28 BC, when the Romans, underAugustus,annexed it into their Republic.[35][36]Dardania eventually became a part of theMoesiaprovince.[37]During the reign ofDiocletian,Dardania became a fullRoman provinceand the entirety of Kosovo's modern territory became a part of theDiocese of Moesia,and then during the second half of the 4th century, it became part of thePraetorian prefecture of Illyricum.[38]: 548

During Roman rule, a series of settlements developed in the area, mainly close to mines and to the major roads. The most important of the settlements wasUlpiana,[39]which is located near modern-dayGračanica.It was established in the 1st century AD, possibly developing from a concentratedDardanianoppidum,and then was upgraded to the status of aRomanmunicipiumat the beginning of the 2nd century during the rule ofTrajan.[40][41]Ulpiana became especially important during the rule ofJustinian I,after the Emperor rebuilt the city after it had been destroyed by an earthquake and renamed it toIustinianna Secunda.[42][43]

Other important towns that developed in the area during Roman rule wereVendenis,located in modern-dayPodujevë;Viciano,possibly nearVushtrri;andMunicipium Dardanorum,an important mining town inLeposavić.Other archeological sites includeÇifllakin Western Kosovo,DresnikinKlina,Pestovain Vushtrri,VërbaninKlokot,PoslishtebetweenVërmicaandPrizren,PaldenicanearHani i Elezit,as well asNerodimë e PoshtmeandNikadinnearFerizaj.The one thing all the settlements have in common is that they are located either near roads, such as ViaLissus-Naissus,or near the mines ofNorth Kosovoand eastern Kosovo. Most of the settlements are archaeological sites that have been discovered recently and are being excavated.

It is also known that the region was Christianised during Roman rule, though little is known regarding Christianity in the Balkans in the three first centuries AD.[44]The first clear mention of Christians in literature is the case of Bishop Dacus of Macedonia, from Dardania, who was present at theFirst Council of Nicaea(325).[45]It is also known that Dardania had aDiocesein the 4th century, and its seat was placed in Ulpiana, which remained theepiscopalcenter of Dardania until the establishment ofJustiniana Primain 535 AD.[46][41]The first known bishop of Ulpiana is Machedonius, who was a member of the council ofSerdika.Other known bishops were Paulus (synodofConstantinoplein 553 AD), and Gregentius, who was sent byJustin ItoEthiopiaandYemento ease problems among different Christian groups there.[46]

Middle Ages

In the next centuries, Kosovo was a frontier province of theRoman,and later of theByzantine Empire,and as a result it changed hands frequently. The region was exposed to an increasing number of raids from the 4th century CE onward, culminating with theSlavic migrationsof the 6th and 7th centuries. Toponymic evidence suggests thatAlbanianwas probably spoken in Kosovo prior to the Slavic settlement of the region.[47][48]The overwhelming presence of towns and municipalities in Kosovo with Slavic in their toponymy suggests that the Slavic migrations either assimilated or drove out population groups already living in Kosovo.[49]

There is one intriguing line of argument to suggest that the Slav presence in Kosovo and southernmost part of the Morava valley may have been quite weak in the first one or two centuries of Slav settlement. Only in the ninth century can the expansion of a strong Slav (or quasi-Slav) power into this region be observed. Under a series of ambitious rulers, the Bulgarians pushed westwards across modern Macedonia and eastern Serbia, until by the 850's they had taken over Kosovo and were pressing on the border ofSerbian Principality.[50]

TheFirst Bulgarian Empireacquired Kosovo by the mid-9th century, but Byzantine control wasrestoredby the late 10th century. In 1072, the leaders of the BulgarianUprising of Georgi Voitehtraveled from their center inSkopjeto Prizren and held a meeting in which they invitedMihailo VojislavljevićofDukljato send them assistance. Mihailo sent his son,Constantine Bodinwith 300 of his soldiers. After they met, the Bulgarian magnates proclaimed him "Emperor of the Bulgarians".[51]Demetrios Chomatenosis the last Byzantine archbishop ofOhridto include Prizren in his jurisdiction until 1219.[52]Stefan Nemanjahad seized the area along theWhite Drinin 1185 to 1195 and the ecclesiastical split of Prizren from the Patriarchate in 1219 was the final act of establishingNemanjićrule.Konstantin Jirečekconcluded, from the correspondence of archbishop Demetrios of Ohrid from 1216 to 1236, that Dardania was increasingly populated by Albanians and the expansion started fromGjakovaandPrizrenarea, prior to the Slavic expansion.[53]

During the 13th and 14th centuries, Kosovo was a political, cultural and religious centre of theSerbian Kingdom.[54]In the late 13th century, the seat of theSerbian Archbishopricwas moved toPeja,and rulers centred themselves betweenPrizrenandSkopje,[55]during which time thousands of Christian monasteries and feudal-style forts and castles were erected,[56]withStefan DušanusingPrizren Fortressas one of his temporary courts for a time. When the Serbian Empire fragmented into a conglomeration of principalities in 1371, Kosovo became the hereditary land of theHouse of Branković.[54][57]During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, parts of Kosovo, the easternmost area located near Pristina, were part of thePrincipality of Dukagjini,which was later incorporated into an anti-Ottoman federation of all Albanian principalities, theLeague of Lezhë.[58]

Medieval Monuments in Kosovois a combinedUNESCO World Heritage Siteconsisting of fourSerbian Orthodoxchurches andmonasteriesinDeçan,Peja,PrizrenandGračanica.The constructions were founded by members of theNemanjić dynasty,a prominent dynasty ofmediaeval Serbia.[59]

Ottoman rule

In 1389, as theOttoman Empireexpanded northwards through the Balkans, Ottoman forces under SultanMurad Imet with a Christian coalition led byMoravian SerbiaunderPrince Lazarin theBattle of Kosovo.Both sides suffered heavy losses and the battle was a stalemate and it was even reported as a Christian victory at first, but Serbian manpower was depleted andde factoSerbian rulers could not raise another equal force to the Ottoman army.[60][61][62][63]

Different parts of Kosovo were ruled directly or indirectly by the Ottomans in this early period. The medieval town ofNovo Brdowas under Lazar's son,Stefanwho became a loyal Ottoman vassal and instigated the downfall ofVuk Brankovićwho eventually joined the Hungarian anti-Ottoman coalition and was defeated in 1395–96. A small part of Vuk's land with the villages of Pristina and Vushtrri was given to his sons to hold as Ottoman vassals for a brief period.[64]

By 1455–57, the Ottoman Empire assumed direct control of all of Kosovo and the region remained part of the empire until 1912. During this period,Islamwas introduced to the region. As Ottoman rule spread, ChristianSerbsfled Kosovo to leave westwards and northwards causing the population of Kosovo to fall dramatically.[65]The continuous emigration from Kosovo reached its peak at theGreat Migrations of the Serbs,which included some Christian Albanians.[66]To compensate for the population loss, the Turks encouraged settlement of non-Slav Muslim Albanians in the wider region of Kosovo.[67][68][69][70][71]By the end of the 18th century, Kosovo would attain an Albanian majority - with Peja, Prizren, Prishtina becoming especially important towns for the local Muslim population.[69][72][73][74]

Although initially stout opponents of the advancing Turks, Albanian chiefs ultimately came to accept the Ottomans as sovereigns. The resulting alliance facilitated the mass conversion of Albanians to Islam. Given that the Ottoman Empire's subjects were divided along religious (rather than ethnic) lines, the spread of Islam greatly elevated the status of Albanian chiefs. Centuries earlier, Albanians of Kosovo were predominantly Christian and Albanians and Serbs for the most part co-existed peacefully. The Ottomans appeared to have a more deliberate approach to converting the Roman Catholic population who were mostly Albanians in comparison with the mostly Serbian adherents of Eastern Orthodoxy, as they viewed the former less favorably due to its allegiance to Rome, a competing regional power.[71]

Rise of nationalism

In the 19th century, there was anawakeningofethnic nationalismthroughout the Balkans. The underlying ethnic tensions became part of a broader struggle of Christian Serbs against Muslim Albanians.[61]The ethnicAlbanian nationalismmovement was centred in Kosovo. In 1878 theLeague of Prizren(Lidhja e Prizrenit) was formed, a political organisation that sought to unify all the Albanians of the Ottoman Empire in a common struggle for autonomy and greater cultural rights,[75]although they generally desired the continuation of the Ottoman Empire.[76]The League was dis-established in 1881 but enabled the awakening of anational identityamong Albanians,[77]whose ambitions competed with those of the Serbs, theKingdom of Serbiawishing to incorporate this land that had formerly been within its empire.

The modern Albanian-Serbian conflict has its roots in theexpulsion of the Albanians in 1877–1878from areas that became incorporated into thePrincipality of Serbia.[78][79]During and after theSerbian–Ottoman War of 1876–78,between 30,000 and 70,000 Muslims, mostly Albanians, were expelled by theSerb armyfrom theSanjak of Nišand fled to theKosovo Vilayet.[80][81][82][83][84][85]According to Austrian data, by the 1890s Kosovo was 70% Muslim (nearly entirely of Albanian descent) and less than 30% non-Muslim (primarily Serbs).[71]In May 1901, Albanians pillaged and partially burned the cities ofNovi Pazar,Sjenicaand Pristina, andkilled many Serbsnear Pristina and in Kolašin (now North Kosovo).[86][87]

In the spring of 1912, Albanians under the lead ofHasan Prishtinarevoltedagainst the Ottoman Empire. The rebels were joined by a wave of Albanians in theOttoman armyranks, who deserted the army, refusing to fight their own kin. The rebels defeated the Ottomans and the latter were forced to accept all fourteen demands of the rebels, which foresaw an effective autonomy for the Albanians living in the Empire.[88]However, this autonomy never materialised, and the revolt created serious weaknesses in the Ottoman ranks, luringMontenegro,Serbia,Bulgaria,andGreeceinto declaring war on the Ottoman Empire and starting theFirst Balkan War.

After the Ottomans' defeat in theFirst Balkan War,the1913 Treaty of Londonwas signed with Metohija ceded to theKingdom of Montenegroand eastern Kosovo ceded to theKingdom of Serbia.[89]During theBalkan Wars,over 100,000 Albanians left Kosovo and about 50,000 were killed in themassacresthat accompanied the war.[90][91]Soon, there were concertedSerbian colonisation effortsin Kosovo during various periods between Serbia's 1912 takeover of the province andWorld War II,causing the population of Serbs in Kosovo to grow by about 58,000 in this period.[92][93]

Serbian authorities promoted creating new Serb settlements in Kosovo as well as the assimilation of Albanians into Serbian society, causing a mass exodus of Albanians from Kosovo.[94]The figures of Albanians forcefully expelled from Kosovo range between 60,000 and 239,807, while Malcolm mentions 100,000–120,000. In combination with the politics of extermination and expulsion, there was also a process of assimilation through religious conversion of Albanian Muslims and Albanian Catholics into the Serbian Orthodox religion which took place as early as 1912. These politics seem to have been inspired by the nationalist ideologies ofIlija GarašaninandJovan Cvijić.[95]

In the winter of 1915–16, duringWorld War I,Kosovo saw the retreat of the Serbian army as Kosovo was occupied byBulgariaandAustria-Hungary.In 1918, theAllied Powerspushed theCentral Powersout of Kosovo.

A new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three districts (oblast) of the Kingdom: Kosovo, Raška and Zeta. In 1929, the country was transformed into theKingdom of Yugoslaviaand the territories of Kosovo were reorganised among theBanate of Zeta,theBanate of Moravaand theBanate of Vardar.In order to change theethnic composition of Kosovo,between 1912 and 1941 alarge-scale Serbian colonisation of Kosovowas undertaken by the Belgrade government. Kosovar Albanians' right to receive education in their own languagewas deniedalongside other non-Slavic or unrecognised Slavic nations of Yugoslavia, as the kingdom only recognised the Slavic Croat, Serb, and Slovene nations as constituent nations of Yugoslavia. Other Slavs had to identify as one of the three official Slavic nations and non-Slav nations deemed as minorities.[94]

Albanians and otherMuslimswere forced to emigrate, mainly with the land reform which struck Albanian landowners in 1919, but also with direct violent measures.[96][97]In 1935 and 1938, two agreements between the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Turkey were signed on the expatriation of 240,000 Albanians to Turkey, but the expatriation did not occur due to the outbreak ofWorld War II.[98]

After theAxis invasion of Yugoslaviain 1941, most of Kosovo was assigned to Italian-controlled Albania, and the rest was controlled by Germany and Bulgaria. A three-dimensional conflict ensued, involving inter-ethnic, ideological, and international affiliations.[99]Albanian collaborators persecuted Serb and Montenegrin settlers.[100]Estimates differ, but most authors estimate that between 3,000 and 10,000 Serbs and Montenegrinsdied in Kosovo during the Second World War.Another 30,000 to 40,000, or as high as 100,000, Serbs and Montenegrins, mainly settlers, were deported to Serbia in order toAlbanianiseKosovo.[99][101]A decree from Yugoslav leaderJosip Broz Tito,followed by a new law in August 1945 disallowed the return of colonists who had taken land from Albanian peasants.[102]During the war years, some Serbs and Montenegrins were sent to concentration camps in Pristina and Mitrovica.[101]Nonetheless, these conflicts were relatively low-level compared with other areas of Yugoslavia during the war years. Two Serb historians also estimate that 12,000 Albanians died.[99]An official investigation conducted by the Yugoslav government in 1964 recorded nearly 8,000 war-related fatalities in Kosovo between 1941 and 1945, 5,489 of them Serb or Montenegrin and 2,177 Albanian.[103]Some sources note that up to 72,000 individuals were encouraged to settle or resettle into Kosovo from Albania by the short-lived Italian administration.[104][101]As the regime collapsed, this was never materialised with historians and contemporary references emphasising that a large-scale migration of Albanians from Albania to Kosovo is not recorded in Axis documents.[105]

Communist Yugoslavia

The existing province took shape in 1945 as theAutonomous Region of Kosovo and Metohija,with a final demarcation in 1959.[106][107]Until 1945, the only entity bearing the name of Kosovo in the late modern period had been the Vilayet of Kosovo, a political unit created by the Ottoman Empire in 1877. However, those borders were different.[108]

Tensions between ethnic Albanians and the Yugoslav government were significant, not only due to ethnic tensions but also due to political ideological concerns, especially regarding relations with neighbouring Albania.[109]Harsh repressive measures were imposed on Kosovo Albanians due to suspicions that there were sympathisers of theStalinistregime ofEnver Hoxhaof Albania.[109]In 1956, a show trial in Pristina was held in which multiple Albanian Communists of Kosovo were convicted of being infiltrators from Albania and given long prison sentences.[109]High-ranking Serbian communist officialAleksandar Rankovićsought to secure the position of the Serbs in Kosovo and gave them dominance in Kosovo'snomenklatura.[110]

Islamin Kosovo at this time was repressed and both Albanians and Muslim Slavs were encouraged to declare themselves to be Turkish and emigrate to Turkey.[109]At the same time Serbs and Montenegrins dominated the government, security forces, and industrial employment in Kosovo.[109]Albanians resented these conditions and protested against them in the late 1960s, calling the actions taken by authorities in Kosovo colonialist, and demanding that Kosovo be made a republic, or declaring support for Albania.[109]

After the ouster of Ranković in 1966, the agenda of pro-decentralisation reformers in Yugoslavia succeeded in the late 1960s in attaining substantial decentralisation of powers, creating substantial autonomy in Kosovo and Vojvodina, and recognising a Muslim Yugoslav nationality.[111]As a result of these reforms, there was a massive overhaul of Kosovo's nomenklatura and police, that shifted from being Serb-dominated to ethnic Albanian-dominated through firing Serbs in large scale.[111]Further concessions were made to the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo in response to unrest, including the creation of theUniversity of Pristinaas anAlbanian languageinstitution.[111]These changes created widespread fear among Serbs that they were being madesecond-class citizensin Yugoslavia.[112]By the 1974 Constitution of Yugoslavia, Kosovo was granted major autonomy, allowing it to have its own administration, assembly, and judiciary; as well as having a membership in the collective presidency and the Yugoslav parliament, in which it held veto power.[113]

In the aftermath of the 1974 constitution, concerns over the rise of Albanian nationalism in Kosovo rose with the widespread celebrations in 1978 of the 100th anniversary of the founding of theLeague of Prizren.[109]Albanians felt that their status as a "minority" in Yugoslavia had made them second-class citizens in comparison with the "nations" of Yugoslavia and demanded that Kosovo be aconstituent republic,alongside the other republics of Yugoslavia.[114]Protests by Albanians in 1981 over the status of Kosovoresulted in Yugoslav territorial defence units being brought into Kosovo and a state of emergency being declared resulting in violence and the protests being crushed.[114]In the aftermath of the 1981 protests, purges took place in the Communist Party, and rights that had been recently granted to Albanians were rescinded – including ending the provision of Albanian professors and Albanian language textbooks in the education system.[114]

While Albanians in the region had the highest birth rates in Europe, other areas of Yugoslavia including Serbia had low birth rates. Increased urbanisation and economic development led to higher settlements of Albanian workers into Serb-majority areas, as Serbs departed in response to the economic climate for more favorable real estate conditions in Serbia.[115]While there was tension, charges of "genocide" and planned harassment have been discredited as a pretext to revoke Kosovo's autonomy. For example, in 1986 the Serbian Orthodox Church published an official claim that Kosovo Serbs were being subjected to an Albanian program of 'genocide'.[116]

Even though they were disproved by police statistics,[116][page needed]they received wide attention in the Serbian press and that led to further ethnic problems and eventual removal of Kosovo's status. Beginning in March 1981, Kosovar Albanian students of the University of Pristina organised protests seeking that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia and demanding their human rights.[117]The protests were brutally suppressed by the police and army, with many protesters arrested.[118]During the 1980s, ethnic tensions continued with frequent violent outbreaks against Yugoslav state authorities, resulting in a further increase in emigration of Kosovo Serbs and other ethnic groups.[119][120]The Yugoslav leadership tried to suppress protests of Kosovo Serbs seeking protection from ethnic discrimination and violence.[121]

Kosovo War

Inter-ethnic tensions continued to worsen in Kosovo throughout the 1980s. In 1989, Serbian PresidentSlobodan Milošević,employing a mix of intimidation and political maneuvering, drastically reduced Kosovo's special autonomous status within Serbia and started cultural oppression of the ethnic Albanian population.[122]Kosovar Albanians responded with anon-violentseparatist movement, employing widespreadcivil disobedienceand creation of parallel structures ineducation, medicalcare, and taxation, with the ultimate goal of achieving theindependence of Kosovo.[123]

In July 1990, the Kosovo Albanians proclaimed the existence of theRepublic of Kosova,and declared it a sovereign and independent state in September 1992.[124]In May 1992,Ibrahim Rugovawas elected its president.[125]During its lifetime, the Republic of Kosova was only officiallyrecognisedby Albania. By the mid-1990s, the Kosovo Albanian population was growing restless, as the status of Kosovo was not resolved as part of theDayton Agreementof November 1995, which ended theBosnian War.By 1996, theKosovo Liberation Army(KLA), an ethnic Albanian guerrillaparamilitary groupthat sought the separation of Kosovo and the eventual creation of aGreater Albania,[126]had prevailed over the Rugova's non-violent resistance movement and launched attacks against the Yugoslav Army and Serbian police in Kosovo, resulting in theKosovo War.[122][127]

By 1998, international pressure compelled Yugoslavia to sign a ceasefire and partially withdraw its security forces. Events were to be monitored byOrganization for Security and Co-operation in Europe(OSCE) observers according to an agreement negotiated byRichard Holbrooke.The ceasefire did not hold and fighting resumed in December 1998, culminating in theRačak massacre,which attracted further international attention to the conflict.[122]Within weeks, a multilateral international conference was convened and by March had prepared a draft agreement known as theRambouillet Accords,calling for the restoration of Kosovo's autonomy and the deployment ofNATOpeacekeepingforces. The Yugoslav delegation found the terms unacceptable and refused to sign the draft. Between 24 March and 10 June 1999,NATO intervenedby bombing Yugoslavia, aiming to force Milošević to withdraw his forces from Kosovo,[128]though NATO could not appeal to any particular motion of theSecurity Council of the United Nationsto help legitimise its intervention. Combined with continued skirmishes between Albanian guerrillas and Yugoslav forces the conflict resulted in a further massive displacement of population in Kosovo.[129]

During the conflict, between 848,000 and 863,000 ethnic Albanians fled or were forcefully driven from Kosovo and an additional 590,000 were internally displaced.[130][131]Some sources claim that thisethnic cleansingof native Albanians was part of a plan known asOperation Horseshoe,described as "Milosevic's final solution to the Kosovo problem."[132][133][134][135]Although the existence and implementation of this operation have not been proven,[136][137]it closely describes the situation with of the Albanian victims and refugees in neighboring countries.

In 1999 more than 11,000 deaths were reported to the office of theInternational Criminal Tribunal for the former YugoslaviaprosecutorCarla Del Ponte.[138]As of 2010[update],some 3,000 people were still missing, including 2,500 Albanians, 400 Serbs and 100Roma.[139]By June, Milošević agreed to a foreign military presence in Kosovo and the withdrawal of his troops. During theKosovo War,over 90,000 Serbian and other non-Albanian refugees fled the province. In the days after the Yugoslav Army withdrew, over 80,000 Serb and other non-Albanian civilians (almost half of 200,000 estimated to live in Kosovo) were expelled from Kosovo, and many of the remaining civilians were victims of abuse.[140][141][142][143][144]After the Kosovo and otherYugoslav Wars,Serbia became home to the highest number of refugees andIDPs(including Kosovo Serbs) in Europe.[145][146][147]

In some villages under Albanian control in 1998, militants drove ethnic Serbs from their homes.[citation needed]Some of those who remained are unaccounted for and are presumed to have been abducted by the KLA and killed. The KLA detained an estimated 85 Serbs during its 19 July 1998attack on Rahovec.35 of these were subsequently released but the others remained. On 22 July 1998, the KLA briefly took control of the Belaćevac mine near the town of Obiliq. Nine Serb mineworkers were captured that day and they remain on theInternational Committee of the Red Cross's list of the missing and are presumed to have been killed.[148]In August 1998, 22 Serbian civilians were reportedly killed in the village of Klečka, where the police claimed to have discovered human remains and a kiln used to cremate the bodies.[148][149]In September 1998, Serbian police collected 34 bodies of people believed to have been seized and murdered by the KLA, among them some ethnic Albanians, at Lake Radonjić near Glođane (Gllogjan) in what became known as theLake Radonjić massacre.[148]Human Rights Watch have raised questions about the validity of at least some of these allegations made by Serbian authorities.[150]

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) prosecuted crimes committed during the Kosovo War. Nine senior Yugoslav officials, including Milošević, were indicted forcrimes against humanityandwar crimescommitted between January and June 1999. Six of the defendants were convicted, one was acquitted, one died before his trial could commence, and one (Milošević) died before his trial could conclude.[152]Six KLA members were charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes by the ICTY following the war, and one was convicted.[153][154][155][156]

In total around 10,317 civilians were killed during the war, of whom 8,676 were Albanians, 1,196 Serbs and 445 Roma and others in addition to 3,218 killed members of armed formations.[157]

Postwar

On 10 June 1999, the UN Security Council passedUN Security Council Resolution 1244,which placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration (UNMIK) and authorisedKosovo Force(KFOR), a NATO-led peacekeeping force. Resolution 1244 provided that Kosovo would have autonomy within the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and affirmed theterritorial integrityof Yugoslavia, which has been legally succeeded by the Republic of Serbia.[158]

Estimates of the number of Serbs who left when Serbian forces left Kosovo vary from 65,000[159]to 250,000.[160]Within post-conflict Kosovo Albanian society, calls for retaliation for previous violence done by Serb forces during the war circulated through public culture.[161]Widespread attacks against Serbian cultural sites commenced following the conflict and the return of hundreds of thousands of Kosovo Albanian refugees to their homes.[162]In 2004, prolonged negotiations over Kosovo's future status, sociopolitical problems and nationalist sentiments resulted in theKosovo unrest.[163][164]11 Albanians and 16 Serbs were killed, 900 people (including peacekeepers) were injured, and several houses, public buildings and churches were damaged or destroyed.

International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged underUN Security Council Resolution 1244.The UN-backed talks, led by UNSpecial EnvoyMartti Ahtisaari,began in February 2006. Whilst progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[165]

In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draftUN Security Council Resolutionwhich proposed 'supervised independence' for the province. A draft resolution, backed by theUnited States,theUnited Kingdomand other European members of theSecurity Council,was presented and rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty.[166]

Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, had stated that it would not support any resolution which was not acceptable to both Belgrade and Kosovo Albanians.[167]Whilst most observers had, at the beginning of the talks, anticipated independence as the most likely outcome, others have suggested that a rapid resolution might not be preferable.[168]

After many weeks of discussions at the UN, the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council formally 'discarded' a draft resolution backing Ahtisaari's proposal on 20 July 2007, having failed to secure Russian backing. Beginning in August, a "Troika"consisting of negotiators from the European Union (Wolfgang Ischinger), the United States (Frank G. Wisner) and Russia (Alexander Botsan-Kharchenko) launched a new effort to reach a status outcome acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina. Despite Russian disapproval, the U.S., the United Kingdom, and France appeared likely to recognise Kosovar independence.[169]A declaration of independence by Kosovar Albanian leaders was postponed until the end of theSerbian presidential elections(4 February 2008). A significant portion of politicians in both the EU and the US had feared that a premature declaration could boost support in Serbia for the nationalist candidate,Tomislav Nikolić.[170]

In November 2001, theOrganization for Security and Co-operation in Europesupervised thefirst electionsfor theAssembly of Kosovo.[171]After that election, Kosovo's political parties formed an all-party unity coalition and electedIbrahim Rugovaas president andBajram Rexhepi(PDK) as Prime Minister.[172]After Kosovo-wide elections in October 2004, the LDK and AAK formed a new governing coalition that did not include PDK and Ora. This coalition agreement resulted inRamush Haradinaj(AAK) becoming Prime Minister, while Ibrahim Rugova retained the position of President. PDK and Ora were critical of the coalition agreement and have since frequently accused that government of corruption.[173]

Parliamentary electionswere held on 17 November 2007. After early results,Hashim Thaçiwho was on course to gain 35 per cent of the vote, claimed victory for PDK, theDemocratic Party of Kosovo,and stated his intention to declare independence. Thaçi formed a coalition with presidentFatmir Sejdiu'sDemocratic Leaguewhich was in second place with 22 percent of the vote.[174]The turnout at the election was particularly low. Most members of the Serb minority refused to vote.[175]

Declaration of independence

Kosovo declared independence fromSerbiaon 17 February 2008.[176]As of 4 September 2020,114 UN statesrecognised its independence, including all of its immediate neighbours, with the exception of Serbia;[177]10 states have subsequently withdrawn that recognition.[178][179]Of the UN Security Council members, while the US, UK and France do recognise Kosovo's independence, Russia and China do not.[180]Since declaring independence, it has become a member of international institutions such as theInternational Monetary FundandWorld Bank,[181][182]though not of the United Nations.

The Serb minority of Kosovo, which largely opposes the declaration of independence, has formed theCommunity Assembly of Kosovo and Metohijain response. The creation of the assembly was condemned by Kosovo's President Fatmir Sejdiu, while UNMIK has said the assembly is not a serious issue because it will not have an operative role.[183] On 8 October 2008, the UN General Assembly resolved, on a proposal by Serbia, to ask theInternational Court of Justiceto render an advisory opinion on the legality of Kosovo's declaration of independence. The advisory opinion, which is not binding over decisions by states to recognise or not recognise Kosovo, was rendered on 22 July 2010, holding that Kosovo's declaration of independence was not in violation either of general principles ofinternational law,which do not prohibit unilateral declarations of independence, nor of specific international law – in particular UNSCR 1244 – which did not define the final status process nor reserve the outcome to a decision of the Security Council.[184]

Some rapprochement between the two governments took place on 19 April 2013 as both parties reached theBrussels Agreement,an agreement brokered by the EU that allowed the Serb minority in Kosovo to have its own police force and court of appeals.[185]The agreement is yet to be ratified by either parliament.[186]Presidents of Serbia and Kosovo organised two meetings, inBrusselson 27 February 2023 andOhridon 18 March 2023, to create and agree upon an 11-point agreement on implementing a European Union-backed deal to normalise ties between the two countries, which includes recognising "each other's documents such as passports and license plates".[187]

A number of protests and demonstrations took place in Kosovo between2021and2023,some of which involved weapons and resulted in deaths on both sides. Amongst the injured were 30 NATO peacekeepers. The main reason behind the 2022–23 demonstrations ended on 1 January 2024 when each country recognised each other's vehicle registration plates.

Governance

|

|

| Vjosa Osmani President |

Albin Kurti Prime Minister |

Kosovo is amulti-partyparliamentaryrepresentative democraticrepublic.It is governed bylegislative,executiveandjudicialinstitutions, which derive from theconstitution,although, until theBrussels Agreement,North Kosovo was in practice largely controlled by institutions of Serbia or parallel institutions funded by Serbia. Legislative functions are vested in both theParliamentand the ministers within their competencies. TheGovernmentexercises the executive power and is composed of thePrime Ministeras thehead of government,the Deputy Prime Ministers and the Ministers of the various ministries.

The judiciary is composed of the Supreme Court and subordinate courts, aConstitutional Court,and independent prosecutorial institutions. There also exist multiple independent institutions defined by the constitution and law, as well as local governments. All citizens are equal before the law andgender equalityis ensured by the constitution.[188][189]The Constitutional Framework guarantees a minimum of ten seats in the 120-member Assembly for Serbs, and ten for other minorities, and also guarantees Serbs and other minorities places in the Government.

Thepresidentserves as thehead of stateand represents the unity of the people, elected every five years, indirectly by the parliament through asecret ballotby a two-thirds majority of all deputies. The head of state is invested primarily with representative responsibilities and powers. The president has the power to return draft legislation to the parliament for reconsideration and has a role in foreign affairs and certain official appointments.[190]ThePrime Ministerserves as thehead of governmentelected by the parliament. Ministers are nominated by the Prime Minister, and then confirmed by the parliament. The head of government exercises executive power of the territory.

Corruption is a major problem and an obstacle to the development of democracy in the country. Those in the judiciary appointed by the government to fight corruption are often government associates. Moreover, prominent politicians and party operatives who commit offences are not prosecuted due to the lack of laws and political will. Organised crime also poses a threat to the economy due to the practices of bribery, extortion and racketeering.[191]

Foreign relations

Theforeign relations of Kosovoare conducted through theMinistry of Foreign AffairsinPristina.As of 2023[update],104 out of 193United Nationsmember statesrecognisethe Republic of Kosovo. Within theEuropean Union,it is recognised by 22 of 27 members and is apotential candidatefor thefuture enlargement of the European Union.[192][193]On 15 December 2022 Kosovo filed a formal application to become a member of the European Union.[21]

Kosovo is a member of several international organisations including theInternational Monetary Fund,World Bank,International Road and Transport Union,Regional Cooperation Council,Council of Europe Development Bank,Venice CommissionandEuropean Bank for Reconstruction and Development.[194]In 2015, Kosovo's bid to become a member ofUNESCOfell three votes short of the two-thirds majority required to join.[195]23 countries maintainembassiesin Kosovo.[196]Kosovo maintains 24diplomatic missionsand 28 consular missions abroad.[197][198]

Therelations with Albaniaare in a special case considering that both countries share the same language and culture. TheAlbanian languageis one of theofficial languagesof Kosovo.Albaniahas an embassy in the capitalPristinaand Kosovo an embassy inTirana.In 1992, Albania was the only country whose parliament voted to recognise theRepublic of Kosova.Albaniawas also one of the first countries to officially announce its recognition of the Republic of Kosovo in February 2008.

From 1 January 2024 Kosovo nationals became exempt from visa requirements within theSchengen Areafor periods of up to 90 days in any 180-day period.[199]

Law

Thejudicial system of Kosovofollows acivil lawframework and comprises regular civil and criminal courts, alongside administrative courts. Administered by thejudicial councilin Pristina, the system includes the supreme court as the highest judicial authority, aconstitutional courtand an independent prosecutorial institution. Following the independence of Kosovo in 2008, theKosovo Policeassumed the primary law enforcement responsibilities within the country.

Covering a broad range of issues related to the status of Kosovo, theAhtisaari Planintroduced two forms of international supervision for Kosovo following its independence, including theInternational Civilian Office(ICO) and theEuropean Union Rule of Law Mission to Kosovo(EULEX).[200]The ICO monitored plan implementation and possessed veto powers, while EULEX focused on developing judicial systems and had arrest and prosecution authority. These bodies were granted powers under Kosovo's declaration of independence and constitution.

The legal status of the ICO depended upon the de facto situation and Kosovo legislation, with oversight provided by theInternational Steering Group(ISG) comprising states that recognied Kosovo. Serbia and non-recognising states did not acknowledge the ICO. Despite initial opposition, EULEX gained acceptance from Serbia and the UN Security Council in 2008. It operated under the UNMIK mandate with operational independence. The ICO concluded operations in 2012 after fulfilling obligations, while EULEX continues to operate within Kosovo and international law. Its role has been extended, primarily focusing on monitoring with reduced responsibilities.[201]

According to the Global Safety Report byGallup,which assesses personal security worldwide through the Law and Order Index Scores for 2023, Kosovo has distinguished itself by ranking among the top ten countries globally in terms of perceived safety and law enforcement effectiveness.[202]

Military

TheKosovo Security Force(KSF) is the national security force of Kosovo commissioned with the task of preserving and safeguarding the country's territorial integrity, national sovereignty and the security interests of its population.[203]Functioning under the president of Kosovo as thecommander-in-chief,the security force adheres to the principle of non-discrimination, guaranteeing equal protection for its personnel regardless of gender or ethnicity.[203][204]Kosovo's notable challenges are identified in the realms of persistent conflicts and societal safety and security, both of which are intertwined with the country's diplomatic ties to neighboring countries and its domestic social and political stability.[205]

TheKosovo Force(KFOR) is aNATO-led internationalpeacekeeping forcein Kosovo.[206]Its operations are gradually reducing untilKosovo's Security Force,established in 2009, becomes self-sufficient.[207]KFOR entered Kosovo on 12 June 1999,[208]one day after theUnited Nations Security Counciladopted theUNSC Resolution 1244.Camp Bondsteelis the operation headquarters of theKosovo Force(KFOR) in Kosovo. It is located nearFerizaj[209]in southeastern Kosovo. It is the Regional Command-East headed by theUnited States Army(U.S. Army) and it is supported by troops fromGreece,Italy,Finland,Hungary,Poland,Slovenia,SwitzerlandandTurkey.

In 2008, under the leadership of NATO, the Kosovo Force (KFOR) and theKosovo Protection Corps(KPC) undertook preparations for the formation of the Kosovo Security Force. A significant milestone occurred in 2014 when the government officially announced its decision to establish a Ministry of Defence by 2019, with the aim of transforming the existing Kosovo Security Force into the Kosovo Armed Forces. This transformation would entail aligning the armed forces with the high standards expected of NATO members, reflecting Kosovo's aspiration to join the alliance in the future.[210]Subsequently, in December 2018, the government enacted legislation to redefine the mandate of the Kosovo Security Force, effecting its transformation into an army. Concurrently, the establishment of a Ministry of Defence was set in motion, further solidifying these developments and ensuring the necessary infrastructure and oversight for the newly formed armed forces.[211]

In 2023, the Kosovo Security Force had over 5,000 active members, using vehicles and weapons acquired from a number of NATO countries. KFOR continues to operate in Kosovo under its UN mandate.[212]

Administrative divisions

Kosovo is divided into sevendistricts(Albanian:rajon;Serbian:okrug), according to the Law of Kosovo and the Brussels Agreement of 2013, which stipulated the formation of new municipalities with Serb majority populations. The districts are further subdivided into 38municipalities(komunë;opština). The largest and most populous district of Kosovo is theDistrict of Pristinawith the capital inPristina,having a surface area of 2,470 km2(953.67 sq mi) and a population of 477,312.

|

Geography

Defined in a total area of 10,887 square kilometres (4,203 square miles), Kosovo islandlockedand located in the center of theBalkan PeninsulainSoutheastern Europe.It lies between latitudes42°and43° N,and longitudes20°and22° E.[213]The northernmost point is Bellobërda at 43° 14' 06 "northern latitude; the southernmost isRestelicëat 41° 56' 40 "northern latitude; the westernmost point isBogëat 20° 3' 23 "eastern longitude; and the easternmost point isDesivojcaat 21° 44' 21 "eastern longitude. The highest point of Kosovo isGjeravicaat 2,656 metres (8,714 ft)above sea level,[214][215][216]and the lowest is theWhite Drinat 297 metres (974 ft).

Most of the borders of Kosovo are dominated by mountainous and high terrain. The most noticeabletopographicalfeatures are theAccursed Mountainsand theŠar Mountains.The Accursed Mountains are a geological continuation of theDinaric Alps.The mountains run laterally through the west along the border withAlbaniaandMontenegro.The southeast is predominantly the Šar Mountains, which constitute the border withNorth Macedonia.Besides the mountain ranges, Kosovo's territory consists mostly of two major plains, theKosovo Plainin the east and theMetohija Plainin the west.

Additionally, Kosovo consists of multiple geographic and ethnographic regions, such asDrenica,Dushkaja,Gollak,Has,Highlands of Gjakova,Llap,LlapushaandRugova.

Kosovo's hydrological resources are relatively small; there are fewlakesin Kosovo, the largest of which areLake Batllava,Badovc Lake,Lake Gazivoda,Lake Radoniq.[217][218]In addition to these, Kosovo also does havekarst springs,thermaland mineral water springs.[219]The longest rivers of Kosovo include theWhite Drin,theSouth Moravaand theIbar.Sitnica,a tributary of Ibar, is the largest river lying completely within Kosovo's territory.Nerodime riverrepresents Europe's only instance of a river bifurcation flowing into theBlack SeaandAegean Sea.

Climate

Most of Kosovo experiences predominantly aContinental climatewithMediterraneanandAlpineinfluences,[220]strongly influenced by Kosovo's proximity to theAdriatic Seain the west, theAegean Seain the south as well as the European continental landmass in the north.[221]

The coldest areas are situated in the mountainous region to the west and southeast, where an Alpine climate is prevalent. The warmest areas are mostly in the extreme southern areas close to the border with Albania, where a Mediterranean climate is the norm. Mean monthly temperature ranges between 0°C(32°F) (in January) and 22 °C (72 °F) (in July). Mean annual precipitation ranges from 600 to 1,300 mm (24 to 51 in) per year, and is well distributed year-round.

To the northeast, theKosovo PlainandIbar Valleyare drier with total precipitation of about 600 millimetres (24 inches) per year and more influenced by continental air masses, with colder winters and very hot summers. In the southwest, climatic area ofMetohijareceives more mediterranean influences with warmer summers, somewhat higher precipitation (700 mm (28 in)) and heavy snowfalls in the winter. The mountainous areas of theAccursed Mountainsin the west,Šar Mountainson the south andKopaonikin the north experiences alpine climate, with high precipitation (900 to 1,300 mm (35 to 51 in) per year), short and fresh summers, and cold winters.[222]The average annual temperature of Kosovo is 9.5 °C (49.1 °F). The warmest month is July with average temperature of 19.2 °C (66.6 °F), and the coldest is January with −1.3 °C (29.7 °F). ExceptPrizrenandIstog,all other meteorological stations in January recorded average temperatures under 0 °C (32 °F).[223]

Biodiversity

Located inSoutheastern Europe,Kosovo receives floral and faunal species from Europe andEurasia.Forests are widespread in Kosovo and cover at least 39% of the region.Phytogeographically,it straddles theIllyrianprovince of theCircumboreal Regionwithin theBoreal Kingdom.In addition, it falls within three terrestrial ecoregions:Balkan mixed forests,Dinaric Mountains mixed forests,andPindus Mountains mixed forests.[224]Kosovo's biodiversity is conserved in twonational parks,elevennature reservesand one hundred three other protected areas.[225]TheBjeshkët e Nemuna National ParkandSharr Mountains National Parkare the most important regions of vegetation and biodiversity in Kosovo.[226]Kosovo had a 2019Forest Landscape Integrity Indexmean score of 5.19/10, ranking it 107th globally out of 172 countries.[227]

Floraencompasses more than 1,800 species ofvascular plantspecies, but the actual number is estimated to be higher than 2,500 species.[228][229]The diversity is the result of the complex interaction of geology and hydrology creating a wide variety of habitat conditions for flora growth. Although, Kosovo represents only 2.3% of the entire surface area of theBalkans,in terms of vegetation it has 25% of the Balkan flora and about 18% of the European flora.[228]The fauna is composed of a wide range of species.[226]: 14 The mountainous west and southeast provide a great habitat for severalrareorendangered speciesincludingbrown bears,lynxes,wild cats,wolves,foxes,wild goats,roebucksanddeers.[230]A total of 255 species ofbirdshave been recorded, with raptors such as thegolden eagle,eastern imperial eagleandlesser kestrelliving principally in the mountains of Kosovo.

Environmental issues

Environmental issues in Kosovo include a wide range of challenges pertaining toairandwater pollution,climate change,waste management,biodiversity lossandnature conservation.[231]The vulnerability of the country to climate change is influenced by various factors, such as increased temperatures, geological and hydrologicalhazards,including droughts, flooding, fires and rains.[231]Kosovo is not a signatory to theUnited Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change(UNFCCC), theKyoto Protocolor theParis Agreement.[232]Consequently, the country is not mandated to submit aNationally Determined Contribution(NDC) that are voluntary commitments outlining a nation's actions and strategies for mitigating climate change and adapting to its impacts.[232]However, since 2021, Kosovo is actively engaged in the process of formulating a voluntary NDC, with assistance provided from Japan.[232][233]In 2023, the country has established a goal of reducinggreenhouse gas emissionsby approximately 16.3% as part of its broader objective to achievecarbon neutralityby the year 2050.[233]

Demographics

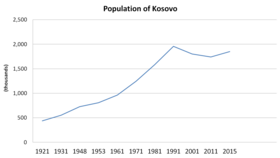

TheAgency of Statisticsestimated Kosovo's population in 2021 to be approximately 1,774,000.[234]In 2023, the overalllife expectancyat birth is 79.68 years; 77.38 years for males and 81.87 years for females.[235]The estimatedtotal fertility ratein 2023 is 1.88 children born per woman.[236]The country is the11th most populous countryin theSoutheastern Europe(Balkans) and ranks as the148th most populous countryin the world. The country's population rose steadily over the 20th century and peaked at an estimated 2.2 million in 1998. TheKosovo Warand subsequent migration have decreased the population of Kosovo over time.

In 2019,Albaniansconstituted 92% of the population of Kosovo, followed by ethnicSerbs(4%),Bosniaks(2%),Turks(1%),Romani(1%), and theGorani(<1%).[238]Albanians constitute the majority of the population in most of Kosovo. Ethnic Serbs are concentrated inthe northof the country, as well as inother municipalitiesin the east of the country, such asGračanicaandŠtrpce.Turks form a local majority in the municipality ofMamusha,just north of Prizren, while the Bosniaks are mainly located within Prizren itself. The Gorani are concentrated in the southernmost tip of the country, inDragash.The Romani are spread across the entire country.

Theofficial languagesof Kosovo areAlbanianandSerbian[2]and the institutions are committed to ensure the equal use of those two official languages of Kosovo.[239]Municipal civil servants are only required to speak one of the two languages in a professional setting and, according to Language Commissioner of Kosovo Slaviša Mladenović, no government organisation has all of its documents available in both languages.[240]The Law on the Use of Languages givesTurkishthe status of an official language in the municipality ofPrizren,irrespective of the size of theTurkish communityliving there.[241]Otherwise,Turkish,BosnianandRomahold the status of official languages at municipal level if the linguistic community represents at least 5% of the total population of municipality.[242][241]Albanian is spoken as afirst languageby all Albanians, as well as some of the Romani people, such as theAshkali and Balkan Egyptians.Serbian, Bosnian, and Turkish are spoken as first languages by their respective communities.

According to theWorld Happiness Report2024, which evaluates the happiness levels of citizens in various countries, Kosovo is currently ranked 29th among a total of 143 nations assessed.[243]

| Rank | Municipality | Population | Rank | Municipality | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pristina | 227,154 | 11 | Lipjan | 54,974 | ||

| 2 | Prizren | 147,428 | 12 | Drenas | 48,054 | ||

| 3 | Ferizaj | 109,345 | 13 | Suharekë | 45,713 | ||

| 4 | Gjilan | 82,901 | 14 | Malisheva | 43,871 | ||

| 5 | Peja | 82,661 | 15 | Rahovec | 41,777 | ||

| 6 | Gjakova | 78,824 | 16 | Skenderaj | 40,632 | ||

| 7 | Podujevë | 71,018 | 17 | Viti | 35,549 | ||

| 8 | Mitrovica | 64,680 | 18 | Istog | 33,066 | ||

| 9 | Kosovo Polje | 64,078 | 19 | Klina | 30,574 | ||

| 10 | Vushtrri | 61,493 | 20 | Dragash | 28,908 | ||

Minorities

The relations betweenKosovar AlbaniansandKosovar Serbshave been hostile since the rise of nationalism in the Balkans during the 19th century.[245]During Communism in Yugoslavia, the ethnic Albanians and Serbs were strongly irreconcilable, with sociological studies during the Tito-era indicating that ethnic Albanians and Serbs rarely accepted each other as neighbors or friends and few held inter-ethnic marriages.[246]Ethnic prejudices, stereotypes and mutual distrust between ethnic Albanians and Serbs have remained common for decades.[246]The level of intolerance and separation between both communities during the Tito-period was reported by sociologists to be worse than that of Croat and Serb communities in Yugoslavia, which also had tensions but held some closer relations between each other.[246]

Despite their planned integration into the Kosovar society and their recognition in the Kosovar constitution, theRomani,Ashkali, and Egyptian communities continue to face many difficulties, such as segregation and discrimination, in housing, education, health, employment and social welfare.[247]Many camps around Kosovo continue to house thousands ofinternally displaced people,all of whom are from minority groups and communities.[248]Because many of the Roma are believed to have sided with the Serbs during the conflict, taking part in the widespread looting and destruction of Albanian property,Minority Rights Group Internationalreport that Romani people encounter hostility by Albanians outside their local areas.[249]A 2020 research report funded by the EU shows that there is a limited scale of trust and overall contact between the major ethnic groups in Kosovo.[250]

Religion

Kosovo is asecular statewith nostate religion;freedom of belief,conscienceandreligionis explicitly guaranteed in theConstitution of Kosovo.[253][188][189]Kosovar society is stronglysecularisedand is ranked first inSouthern Europeand ninth in the world as free and equal for tolerance towardsreligionandatheism.[254][255]

In the 2011 census, 95.6% of the population of Kosovo was counted asMuslimand 3.7% asChristianincluding 2.2% asRoman Catholicand 1.5% asEastern Orthodox.[251]The remaining 0.3% of the population reported having no religion, or another religion, or did not provide an adequate answer. Protestants, although recognised as a religious group in Kosovo by the government, were not represented in the census. The census was largely boycotted by theKosovo Serbs,who predominantly identify asSerbian OrthodoxChristians, especially inNorth Kosovo,[256]leaving the Serb population underrepresented.[257]

Islamis the most widely practiced religion in Kosovo and was introduced in theMiddle Agesby theOttomans.Today, Kosovo has the second-highest number of Muslims as a percentage of its population in Europe after Turkey.[258]The majority of the Muslim population of Kosovo are ethnicAlbanians,Turks,and Slavs such asGoraniandBosniaks.[259]

Followers of theRoman Catholic Churchare predominantly Albanians while ethnic Serbs follow theEastern Orthodox Church.In 2008, Protestant pastor Artur Krasniqi, primate of the Kosovo Protestant Evangelical Church, claimed that "as many as 15,000" Kosovar Albanians had converted to Protestantism since 1985.[260]

Relations between the Albanian Muslim and Albanian Catholic communities in Kosovo are good; however, both communities have few or no relations with theSerbian Orthodoxcommunity. In general, the Albanians define theirethnicityby language and not by religion, while religion reflects a distinguishing identity feature among the Slavs of Kosovo and elsewhere.[261]

Economy

Theeconomy of Kosovois a transitional economy. It suffered from the combined results of political upheaval, the Serbian dismissal of Kosovo employees and the followingYugoslav Wars.Despite declining foreign assistance, the GDP has mostly grown since its declaration of independence. This was despite thefinancial crisis of 2007–2008and the subsequentEuropean debt crisis.Additionally, theinflation ratehas been low. Most economic development has taken place in the trade, retail and construction sectors. Kosovo is highly dependent on remittances from thediaspora,foreign direct investment,and other capital inflows.[262]In 2018, theInternational Monetary Fundreported that approximately one-sixth of the population lived below the poverty line and one-third of the working age population was unemployed, the highest rate in Europe.[263]

Kosovo's largest trading partners are Albania, Italy, Switzerland, China, Germany and Turkey. TheEurois its official currency.[264]TheGovernment of Kosovohas signed free-trade agreements withAlbania,Croatia,Bosnia and HerzegovinaandNorth Macedonia.[265][266][267][268]Kosovo is a member ofCEFTA,agreed withUNMIK,and enjoys free trade with most nearby non-European Unioncountries.[269]

Kosovo is dominated by the services sector, accounting for 54% of GDP and employing approximately 56.6% of the population.[270]The industry accounted for 37.3% ofGDPand employs roughly 24.8% of the labour force.[270]There are several reasons for the stagnation, ranging from consecutive occupations, political turmoil and theWar in Kosovoin 1999.[271]While agriculture accounts for only 6.6% of GDP, albeit an increase of 0.5 percentage points from 2019, it forms 18.7% of Kosovo's workforce, the highest proportion of agricultural employment in the region afterAlbania.[270]

Kosovo has large reserves oflead,zinc,silver,nickel,cobalt,copper,ironandbauxite.[275]The nation has the fifth-largestlignitereserves in the world and the third in Europe.[276]The Directorate for Mines and Minerals and theWorld Bankestimated that Kosovo had €13.5 billion worth of minerals in 2005.[277]The primary sector is based on small to medium-sized family-owned dispersed units.[278]53% of the nation's area is agricultural land, 41% forest and forestry land, and 6% for others.[279]

Winehas historically been produced in Kosovo. The main heartland of Kosovo's wine industry is inRahovec.The main cultivars includePinot noir,Merlot,andChardonnay.Kosovo exports wines to Germany and the United States.[280]The four state-owned wine production facilities were not as much "wineries" as they were "wine factories". Only the Rahovec facility that held approximately 36% of the total vineyard area had the capacity of around 50 million litres annually. The major share of the wine production was intended for exports. At its peak in 1989, the exports from theRahovecfacility amounted to 40 million litres and were mainly distributed to the German market.[281]

Energy

Theelectricity sector in Kosovois considered one of the sectors with the greatest potential of development.[282]Kosovo's electricity sector is highly dependent on coal-fired power plants, which use the abundant lignite, so efforts are being made to diversify electricity generation with more renewables sources, such aswind farms in Bajgora and Kitka.[283][284]

A joint energy bloc between Kosovo and Albania, is in work after an agreement which was signed in December 2019.[285]With that agreement Albania and Kosovo will now be able to exchange energy reserves, which is expected to result in €4 million in savings per year for Kosovo.[286]

Tourism

The natural values of Kosovo represent quality tourism resources. The description of Kosovo's potential in tourism is closely related to its geographical location, in the center of theBalkan PeninsulainSoutheastern Europe.It represents a crossroads which historically dates back toantiquity.Kosovo serves as a link in the connection betweenCentralandSouthern Europeand theAdriatic SeaandBlack Sea.Kosovo is generally rich in various topographical features, including highmountains,lakes,canyons,steeprock formationsandrivers.[287]The mountainous west and southeast of Kosovo has great potential for winter tourism. Skiing takes place at theBrezovica ski resortwithin theŠar Mountains,[287]with the close proximity to thePristina Airport(60 km) andSkopje International Airport(70 km) which is a popular destination for international tourists.

Kosovo also has lakes likeLake Batllavathat serves as a popular destination for watersports, camping, and swimming.[288]Other lakes include Ujmani Lake,Liqenati Lake,Zemra Lake.[288]

Other major attractions include the capital,Pristina,the historical cities ofPrizren,PejaandGjakovabut alsoFerizajandGjilan.

The New York Timesincluded Kosovo on the list of 41 places to visit in 2011.[289][290]

Transport

Road transportation of passengers and freight is the most common form of transportation in Kosovo. There are two main motorways in Kosovo: theR7connecting Kosovo withAlbaniaand theR6connectingPristinato the Macedonian border atHani i Elezit.The construction of theR7.1 Motorwaybegan in 2017.

TheR7 Motorway(part ofAlbania-Kosovo Highway) links Kosovo toAlbania'sAdriaticcoast inDurrës.Once the remainingEuropean route (E80)fromPristinatoMerdaresection project will be completed, the motorway will link Kosovo through the presentEuropean route (E80)highway with thePan-European corridor X(E75) nearNišin Serbia. TheR6 Motorway,forming part of theE65,is the second motorway constructed in the region. It links the capitalPristinawith the border with North Macedonia atHani i Elezit,which is about 20 km (12 mi) fromSkopje.Construction of the motorway started in 2014 and finished in 2019.[291]

Trainkosoperates daily passenger trains on two routes:Pristina–Fushë Kosovë–Pejë,as well asPristina–Fushë Kosovë–Ferizaj–Skopje,North Macedonia(the latter in cooperation withMacedonian Railways).[292]Also, freight trains run throughout the country.

The nation hosts two airports,Pristina International AirportandGjakova Airport.Pristina International Airport is located southwest ofPristina.It is Kosovo's only international airport and the only port of entry for air travelers to Kosovo. Gjakova Airport was built by theKosovo Force(KFOR) following theKosovo War,next to an existing airfield used for agricultural purposes, and was used mainly for military and humanitarian flights. The local and national government plans to offerGjakova Airportfor operation under a public-private partnership with the aim of turning it into a civilian and commercial airport.[293]

Infrastructure

Health

In the past, Kosovo's capabilities to develop a modernhealth caresystem were limited.[294]LowGDPduring 1990 worsened the situation even more. However, the establishment of Faculty of Medicine in theUniversity of Pristinamarked a significant development in health care. This was also followed by launching different health clinics which enabled better conditions for professional development.[294]

Nowadays the situation has changed, and the health care system in Kosovo is organised into three sectors:primary,secondary and tertiary health care.[295]Primary health care inPristinais organised into thirteen family medicine centres[296]and fifteen ambulatory care units.[296]Secondary health care is decentralised in seven regional hospitals. Pristina does not have any regional hospital and instead uses University Clinical Center of Kosovo for health care services.University Clinical Center of Kosovoprovides its health care services in twelve clinics,[297]where 642 doctors are employed.[298]At a lower level, home services are provided for several vulnerable groups which are not able to reach health care premises.[299]Kosovo health care services are now focused on patient safety, quality control and assisted health.[300]

Education

Education for primary, secondary, and tertiary levels is predominantly public and supported by the state, run by theMinistry of Education.Education takes place in two main stages: primary and secondary education, and higher education.

The primary and secondary education is subdivided into four stages: preschool education, primary and low secondary education, high secondary education and special education. Preschool education is for children from the ages of one to five. Primary and secondary education is obligatory for everyone. It is provided by gymnasiums and vocational schools and also available in languages of recognised minorities in Kosovo, where classes are held inAlbanian,Serbian,Bosnian,TurkishandCroatian.The first phase (primary education) includes grades one to five, and the second phase (low secondary education) grades six to nine. The third phase (high secondary education) consists of general education but also professional education, which is focused on different fields. It lasts four years. However, pupils are offered possibilities of applying for higher or university studies. According to theMinistry of Education,children who are not able to get a general education are able to get a special education (fifth phase).[301] Higher education can be received in universities and other higher-education institutes. These educational institutions offer studies forBachelor,MasterandPhDdegrees. The students may choose full-time or part-time studies.

Media

Kosovo ranks 56th out of 180 countries in the 2023Press Freedom Indexreport compiled by theReporters Without Borders.[302]TheMediaconsists of different kinds of communicative media such as radio, television, newspapers, and internet web sites. Most of the media survive from advertising and subscriptions. As according to IREX there are 92 radio stations and 22 television stations.[303]

Culture

Cuisine

Kosovar cuisineis distinguished by multifaceted culinary influences derived fromBalkan,Mediterranean,andOttomantraditions.[304]This combination reflects Kosovo's diverse historical and cultural contexts while highlighting itsAlbanian heritage.[304][305]A paramount aspect of this tradition is the principle of hospitality, as articulated in theKanun,which guides various aspects of social interactions and practices.[306]Particularly, the notion "the house of an Albanian belongs to God and to the guest" underscores the high regard on treating guests with respect and generosity.[306]Flistands out for its unique preparation, which involves layering batter and cream in a special pan called a saç, baked slowly over several hours.[307]Pite, a savory pie filled with a mixture of meat, cheese, or spinach, is often enjoyed as a hearty meal throughout Kosovo. Another popular dish isByrek,a flaky pastry that can be filled with a variety of ingredients, including meat, spinach, or cheese, and is often prepared in circular pans.[307]Qebapaare hand-rolled sausages, traditionally made from a blend of minced beef and other meats, are seasoned with a mix of spices such as garlic and black pepper.[304]They are commonly served alongside freshly baked bread, raw onions andajvar,a popular savory red pepper, eggplant and garlic spread that complements the dish.[304]Petulla, or fried dough balls also known as Llokuma, are often drizzled with honey or sprinkled with sugar. Reçel, a type of fruit preserve, is made from various fruits and often used as a spread on bread or served alongside petulla.

Bakllavëis a traditional dessert in Southern Europe, comprising layers of phyllo pastry filled with nuts and drizzled with honey that is often served for festive occasions.[307]Another notable dessert isTrileçe,a sponge cake soaked in a blend of three types of milk and covered with caramel.[307]The coffee culture of Kosovo represents a vibrant and essential aspect of daily life, functioning as a cornerstone for social interactions and communal gatherings.[307]In Kosovo, coffee symbolises hospitality and community, inviting both locals and visitors to connect.[307]Often accompanied by traditional sweets and pastries, the preparation of coffee typically involves a cezve, a traditional pot for brewing finely ground coffee. This method emphasises the ceremonial nature of coffee preparation. Hosts take pride in serving their guests the finest brew, highlighting the importance of hospitality. The act of sharing coffee fosters meaningful conversations among individuals, with people recounting stories and engaging in discussions about life.[307]

Sports