Langues d'oïl

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(May 2017) |

| Oïl | |

|---|---|

| Langues d'oïl, French | |

| Geographic distribution | Northern and centralFrance,southernBelgium,Switzerland,Guernsey,Jersey,Sark |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European |

Early forms | |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | oila1234 cent2283(Central Oil) |

| |

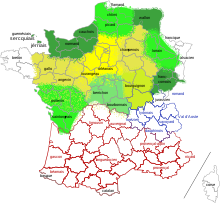

Thelangues d'oïl(/dɔɪ(l)/doy(l),[3]USalso/dɔːˈiːl/daw-EEL,[4][5][Note 1]French:[lɑ̃ɡdɔjl][6]) are adialect continuumthat includes standardFrenchand its closestautochthonousrelatives historically spoken in the northern half ofFrance,southernBelgium,and theChannel Islands.They belong to the larger category ofGallo-Romance languages,which also include the historical languages of east-central France and westernSwitzerland,southern France,portions ofnorthern Italy,theVal d'AraninSpain,and under certain acceptations those ofCatalonia.

Linguists divide theRomance languagesofFrance,and especially ofMedieval France,into two main geographical subgroups: thelangues d'oïlto the North, and thelangues d'ocin the Southern half of France. Both groups are named after the word for "yes" in them or their recent ancestral languages. The most common modernlangue d'oïlis standard French, in which the ancestral "oïl" has become "oui".

Terminology[edit]

Langue d'oïl(in the singular),Oïl dialectsandOïl languages(in the plural) designate the ancient northern Gallo-Romance languages as well as their modern-day descendants. They share many linguistic features, a prominent one being the wordoïlforyes.(Ocwas and still is the southern word foryes,hence thelangue d'ocorOccitan languages). The most widely spoken modern Oïl language isFrench(oïlwas pronounced[o.il]or[o.i],which has become[wi],in modern Frenchoui).[7]

There are three uses of the termoïl:

- Langue d'oïl

- Oïl dialects

- Oïl languages

Langue d'oïl[edit]

In the singular,langue d'oïlrefers to the mutually intelligible linguistic variants oflingua romanaspoken since the 9th century in northern France and southern Belgium (Wallonia), since the 10th century in theChannel Islands,and between the 11th and 14th centuries inEngland(theAnglo-Norman language).Langue d'oïl,the term itself, has been used in the singular since the 12th century to denote this ancient linguistic grouping as a whole. With these qualifiers,langue d'oïlsometimes is used to mean the same asOld French(seeHistorybelow).[8]

Oïl dialects[edit]

In the plural,Oïl dialectsrefer to thevarietiesof the ancientlangue d'oïl.[citation needed]

Oïl languages[edit]

Oïl languagesare those modern-day descendants that evolved separately from the varieties of the ancientlangue d'oïl.Consequently,langues d'oïltoday may apply either: to all the modern-day languages of this familyexceptthe French language; or to this familyincludingFrench. "Oïldialects "or" French dialects "are also used to refer to theOïl languages except French—as some extant Oïl languages are very close to modern French. Because the termdialectis sometimes considered pejorative, the trend today among French linguists is to refer to these languages aslangues d'oïlrather thandialects.[citation needed]

Varieties[edit]

This sectionrelies largely or entirely on asingle source.(September 2022) |

Five zones of partiallymutually intelligibleOïl dialects have been proposed:[9]

Frankish zone (zone francique)[edit]

- Picard

- Walloon

- Lorrain

- NorthernNorman(spoken north of theJoret line) including:Anglo-Norman;Dgèrnésiais(spoken inGuernsey),Jèrriais(spoken in Jersey),Auregnais(spoken in Alderney),Sercquiais(spoken in Sark)

- Eastern Champenois

Francienzone (zone francienne)[edit]

Non-standard varieties:

- Orléanais

- Tourangeau,not to be confused with theFrench language in Touraine

- Berrichon

- Bourbonnais

- Western Champenois(or Eastern Francien)

Burgundianzone (zone burgonde)[edit]

Armoricanzone (zone armoricaine)[edit]

- Eastern Armorican:Angevin;Mayennais;Manceau(SarthoisandPercheron); SouthernNorman(spoken south of theJoret line)

- Western Armorican:Gallo

Gallo has a stronger Celtic substrate fromBreton.Gallo originated from the oïl speech of people from eastern and northern regions:Anjou;Maine(MayenneandSarthe); andNormandy;who were in contact with Breton speakers inUpper Brittany.SeeMarches of Neustria

Poitevin-Saintongeaiszone (zone poitevineandzone saintongeaise)[edit]

Named after the former provinces ofPoitouandSaintonge

Development[edit]

For the history of phonology, orthography, syntax and morphology, seeHistory of the French languageand the relevant individual Oïl language articles.

Each of the Oïl languages has developed in its own way from the common ancestor, and division of the development into periods varies according to the individual histories. Modern linguistics uses the following terms:

- 9th–13th centuries

- Old French

- Old Norman

- etc.

- French

- Middle Frenchfor the period 14th–15th centuries

- 16th century:françaisrenaissance(Renaissance French)

- 17th to 18th century:français classique(Classical French)

History[edit]

Romana lingua[edit]

In the 9th century,romana lingua(the term used in theOaths of Strasbourgof 842) was the first of the Romance languages to be recognized by its speakers as a distinct language, probably because it was the most different fromLatincompared with the other Romance languages (seeHistory of the French language).

Many of the developments that are now considered typical ofWalloonappeared between the 8th and 12th centuries. Walloon "had a clearly defined identity from the beginning of the thirteenth century". In any case, linguistic texts from the time do not mention the language, even though they mention others in the Oïl family, such as Picard and Lorrain. During the 15th century, scribes in the region called the language "Roman" when they needed to distinguish it. It is not until the beginning of the 16th century that we find the first occurrence of the word "Walloon" in the same linguistic sense that we use it today.

Langue d'oïl[edit]

By late- or post-Roman timesVulgar Latinwithin France had developed two distinctive terms for signifying assent (yes):hoc ille( "this (is) it" ) andhoc( "this" ), which becameoïlandoc,respectively. Subsequent development changed "oïl" into "oui", as in modern French. The termlangue d'oïlitself was first used in the 12th century, referring to the Old French linguistic grouping noted above. In the 14th century, the Italian poetDantementioned theyesdistinctions in hisDe vulgari eloquentia.He wrote inMedieval Latin:"nam alii oc, alii si, alii vero dicunt oil"(" some say 'oc', others say 'sì', others say 'oïl' ")—thereby distinguishing at least three classes of Romance languages:oc languages(in southern France);si languages(inItalyandIberia) andoïl languages(in northern France).[citation needed]

Other Romance languages derive their word for "yes" from the classical Latinsic,"thus", such as theItaliansì,SpanishandCatalansí,Portuguesesim,and evenFrenchsi(used when contradicting another's negative assertion).Sardinianis an exception in that its word for "yes",eja,is from neither origin.[10]SimilarlyRomanianusesdafor "yes", which is of Slavic origin.[11]

However, neitherlingua romananorlangue d'oïlreferred, at their respective time, to a single homogeneous language but tomutually intelligible linguistic varieties.In those times, spoken languages in Western Europe were not codified (except Latin and Medieval Latin), the region's population was considerably lower than today, and population centers were more isolated from each other. As a result, mutually intelligible linguistic varieties were referred to as one language.[citation needed]

French (Old French/Standardized Oïl) or lingua Gallicana[edit]

In the 13th century these varieties were recognized and referred to asdialects( "idioms" ) of a single language, thelangue d'oïl.However, since the previous centuries a common literary and juridical "interdialectary" langue d'oïl had emerged, a kind ofkoiné.In the late 13th century this common langue d'oïl was namedFrench(françoisin French,lingua gallicaorgallicanain Medieval Latin). Both aspects of"dialects of a same language"and"French as the common langue d'oïl"appear in a text ofRoger Bacon,Opus maius,who wrote in Medieval Latin but translated thus: "Indeed, idioms of a same language vary amongst people, as it occurs in the French language which varies in an idiomatic manner amongst the French,Picards,NormansandBurgundians.And terms right to the Picards horrify the Burgundians as much as their closer neighbours the French ".[citation needed]

It is from this period though that definitions of individual Oïl languages are first found. The Picard language is first referred to by name as"langage pikart"in 1283 in theLivre Roisin.The author of theVie du bienheureux Thomas Hélye de Bivillerefers to the Norman character of his writing. TheSermons poitevinsof around 1250 show the Poitevin language developing as it straddled the line between oïl and oc.

As a result, in modern times the termlangue d'oïlalso refers to thatOld Frenchwhich was not as yet namedFrenchbut was already—before the late 13th century—used as a literary and juridicalinterdialectary language.

The termFrancienis a linguisticneologismcoined in the 19th century to name the hypothetical variant of Old French allegedly spoken by thelate 14th centuryin the ancient province ofPays de France—the thenParisregion later calledÎle-de-France.ThisFrancien,it is claimed, became the Medieval French language. Current linguistic thinking mostly discounts theFrancientheory, although it is still often quoted in popular textbooks. The termfrancienwas never used by those people supposed to have spoken the variant; but today the term could be used to designate that specific10th-and-11th centuriesvariant of langue d'oïl spoken in the Paris region; both variants contributed to the koine, as both were calledFrenchat that time.

Rise of French (Standardized Oïl) versus other Oïl languages[edit]

For political reasons it was in Paris and Île-de-France that this koiné developed from a written language into a spoken language. Already in the 12th centuryConon de Béthunereported about the French court who blamed him for using words ofArtois.

By the late 13th century the written koiné had begun to turn into aspoken and written standard language,and was namedFrench.Since then French started to be imposed on the other Oïl dialects as well as on the territories oflangue d'oc.

However, the Oïl dialects andlangue d'occontinued contributing to the lexis of French.

In 1539 the French language was imposed by theOrdinance of Villers-Cotterêts.It required Latin be replaced in judgements and official acts and deeds. The local Oïl languages had always been the language spoken in justice courts. The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts was not intended to make French a national language, merely a chancery language for law and administration. Although there were competing literary standards among the Oïl languages in the mediæval period, the centralisation of theFrench kingdomand its influence even outside its formal borders sent most of the Oïl languages into comparative obscurity for several centuries. The development of literature in this new language encouraged writers to use French rather than their ownregional languages.This led to the decline ofvernacular literature.

It was theFrench Revolutionwhich imposed French on the people as the official language in all the territory. As the influence of French (and in the Channel Islands, English) spread among sectors of provincial populations, cultural movements arose to study and standardise the vernacular languages. From the 18th century and into the 20th century, societies were founded (such as the "Société liégoise de Littérature wallonne" in 1856), dictionaries (such asGeorge Métivier'sDictionnaire franco-normandof 1870) were published, groups were formed and literary movements developed to support and promote the Oïl languages faced with competition. The Third Republic sought to modernise France and established primary education where the only language recognised was French. Regional languages were discouraged, and the use of French was seen as aspirational, accelerating their decline.[12]This was also generally the case in areas where Oïl languages were spoken. French is now the best-known of the Oïl languages.

Literature[edit]

Besides the influence ofFrench literature,small-scale literature has survived in the other Oïl languages. Theatrical writing is most notable inPicard(which maintains a genre of vernacularmarionettetheatre),PoitevinandSaintongeais.Oral performance (story-telling) is a feature ofGallo,for example, whileNormanandWalloonliterature, especially from the early 19th century tend to focus on written texts and poetry (see, for example,WaceandJèrriais literature).

As the vernacular Oïl languages were displaced from towns, they have generally survived to a greater extent in rural areas - hence a preponderance of literature relating to rural and peasant themes. The particular circumstances of the self-governing Channel Islands developed a lively strain of political comment, and the early industrialisation in Picardy led to survival of Picard in the mines and workshops of the regions. The mining poets of Picardy may be compared with the tradition of rhymingWeaver PoetsofUlster Scotsin a comparable industrial milieu.

There are some regional magazines, such asCh'lanchron(Picard),Le Viquet(Norman),Les Nouvelles Chroniques du Don Balleine[1](Jèrriais), andEl Bourdon(Walloon), which are published either wholly in the respective Oïl language or bilingually with French. These provide a platform for literary writing.

Status[edit]

Apart from French, an official language in many countries (seelist), the Oïl languages have enjoyed little status in recent times.

Currently Walloon,Lorrain(under the local name ofGaumais), andChampenoishave the status of regional languages ofWallonia.

The Norman languages of the Channel Islands enjoy a certain status under the governments of theirBailiwicksand within the regional and lesser-used language framework of theBritish-Irish Council.TheAnglo-Norman language,a variant of Norman once the official language of England, today holds mostly a place of ceremonial honour in the United Kingdom (now referred to asLaw French).

The French government recognises the Oïl languages aslanguages of France,but theConstitutional Council of Francebarred ratification of theEuropean Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[13]

Influence[edit]

Thelangues d'oïlwere more or less influenced by the native languages of the conqueringGermanic tribes,notably theFranks.This was apparent not so much in the vocabulary (which remained overwhelmingly of Latin origin) as in the phonology and syntax; the invading Franks, Burgundians and Normans became the rulers and their accents were imposed as standard on the rest of the population. This accounts in large part for the relative distinctiveness of French compared to other Romance languages.

TheEnglish languagewas heavily influenced by contact with Norman following theNorman Conquestand much of the adopted vocabulary shows typically Norman features.

Portuguese was heavily influenced by more than a millennium of perennial contact with several dialects of both Oïl andOccitan languagegroups, in lexicon (up to 15–20% in some estimates, at least 5000 word roots), phonology and orthography.[14][15][16]The influence of Occitan was, nevertheless, the most marked, through the status Provençal in particular achieved in southwestern Europe around thetroubadourapex in the Middle Ages, whenGalician-Portuguese lyricwas developed. Aside the direct influence of Provençal literature, the presence of languages from modern-day France in the Galician-Portuguese area was also strong due to the rule of theHouse of Burgundy,the establishment of the Orders ofClunyandCister,the manysectionsof theWay of St. Jamespilgrimage route that come from elsewhere in Europe out of the Iberian Peninsula, and the settlement in Iberia of people from the other side of the Pyrenees, arriving during and after theReconquista.[17][18]

Theanti-Portuguese factorofBrazilian nationalismin the 19th century led to an increased use of the French language in detriment of Portuguese, as France was seen at the time as a model of civilization and progress.[19]The learning of French has historically been important and strong among the Lusophone elites, and for a great span of time it was also the foreign language of choice among the middle class of both Portugal and Brazil, only surpassed in theglobalisedpostmodernityby English.[20][21][22][23]

TheFrench spoken in Belgiumshows some influence fromWalloon.[citation needed]

The development of French inNorth Americawas influenced by the speech of settlers originating from northwestern France, many of whom introduced features of their Oïl varieties into the French they spoke. (See alsoFrench language in the United States,French language in Canada)

Languages and dialects with significant Oïl influence[edit]

- allregional languagesspokenin France,Belgium,andLuxembourg

- Limburgish,particularlyMaastrichtian

- allFrench-based creole languages

- English(Oïl influences on vocabulary, transmitted via theAnglo-Norman languagespoken by theupper classesin England in the centuries following theNorman Conquest,and later from French)

- Portuguese(Oïl and Occitan influences on lexicon, phonology—especiallyEuropean,Macaneseand EuropeanizedBrazilianandAfricandialects—, and orthography)

- Franco-Italian,a mixed language of Old French andVenetianorLombardused in literary works of northern Italy in the 13th and 14th centuries.

See also[edit]

- Moselle Romance,an extinct Romance speech, most likely alangue d'oïl

- Old French

- Bartsch's law

- Lenga d'òc

- Language policy of France

Footnotes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^abHammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2022-05-24)."Glottolog 4.8 - Oil".Glottolog.Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-11-11.Retrieved2023-11-11.

- ^Centre national de la recherche scientifique (2020)."Atlas sonore des langues régionales de France".atlas.limsi.fr.Paris..

- ^Oxford Dictionaries

- ^Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- ^American Heritage Dictionary

- ^LePetit Robert1,1990

- ^"oui".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^"langue d'oïl".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^Manuel pratique de philologie romane,Pierre Bec, 1970–1971

- ^Alkire, Ti; Rosen, Carol (2010).Romance languages: a historical introduction.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521889155.

- ^"DA - DEX online"(in Romanian).Retrieved2014-08-11.

- ^Lodge, Anthony (4 March 1993).French, from dialect to standard.Routledge.ISBN978-0415080712.

- ^Constitutional Council Decision 99-412 DC, European Charter for regional or minority languages

- ^(in Portuguese)Exhibition at the Museum of the Portuguese Language shows the French influence in our language

- ^(in Portuguese)Contacts between French and Portuguese or the first's influences on the secondArchived2013-07-31 at theWayback Machine

- ^(in Portuguese)The influence of loanwords in the Portuguese language: a process of globalization, ideology and communicationArchived2013-09-21 at theWayback Machine

- ^A língua que falamos: Português, história, variação e discursoLuiz Antônio da Silva, 2005.

- ^Occitejano: Sobre a origem occitana do subdialeto do Alto Tejo portuguêsPaulo Feytor Pinto, 2012.

- ^Barbosa, Rosana (2009).Immigration and Xenophobia: Portuguese Immigrants in Early 19th Century Rio de Janeiro.United States:University Press of America.ISBN978-0-7618-4147-0.,p. 19

- ^(in Portuguese)The importance of the French language in Brazil: marks and milestones in the early periods of teaching

- ^(in Portuguese)Presence of the French language and literature in Brazil – for a history of Franco-Brazilian bonds of cultural affectionArchived2013-09-21 at theWayback Machine

- ^(in Portuguese)What are the French thinking influences still present in Brazil?Archived2015-05-17 at theWayback Machine

- ^(in Portuguese)France in Brazil Year – the importance of cultural diplomacy

Bibliography[edit]

- Paroles d'Oïl,Défense et promotion des Langues d'Oïl, Mougon 1994,ISBN2-905061-95-2

- Les langues régionales,Jean Sibille, 2000,ISBN2-08-035731-X