Late Cretaceous

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(February 2024) |

| Late/Upper Cretaceous | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronology | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Etymology | |||||||||

| Chronostratigraphic name | Upper Cretaceous | ||||||||

| Geochronological name | Late Cretaceous | ||||||||

| Name formality | Formal | ||||||||

| Usage information | |||||||||

| Celestial body | Earth | ||||||||

| Regional usage | Global (ICS) | ||||||||

| Time scale(s) used | ICS Time Scale | ||||||||

| Definition | |||||||||

| Chronological unit | Epoch | ||||||||

| Stratigraphic unit | Series | ||||||||

| Time span formality | Formal | ||||||||

| Lower boundary definition | FADof thePlanktonic ForaminiferRotalipora globotruncanoides | ||||||||

| Lower boundary GSSP | Mont Risoux,Hautes-Alpes,France 44°23′33″N5°30′43″E/ 44.3925°N 5.5119°E | ||||||||

| Lower GSSP ratified | 2002[2] | ||||||||

| Upper boundary definition | Iridiumenriched layer associated with a major meteorite impact and subsequentK-Pg extinction event. | ||||||||

| Upper boundary GSSP | El Kef Section,El Kef,Tunisia 36°09′13″N8°38′55″E/ 36.1537°N 8.6486°E | ||||||||

| Upper GSSP ratified | 1991 | ||||||||

TheLate Cretaceous(100.5–66Ma) is the younger of twoepochsinto which theCretaceousPeriodis divided in thegeologic time scale.Rock stratafrom this epoch form theUpper CretaceousSeries.The Cretaceous is named aftercreta,the Latin word for the whitelimestoneknown aschalk.The chalk of northern France and thewhite cliffs of south-eastern Englanddate from the Cretaceous Period.[3]

Climate[edit]

During the Late Cretaceous, the climate was warmer than present, although throughout the period a cooling trend is evident.[4]Thetropicsbecame restricted to equatorial regions and northernlatitudesexperienced markedly more seasonal climatic conditions.[4]

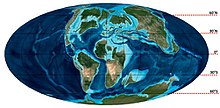

Geography[edit]

Due toplate tectonics,the Americas were gradually moving westward, causing the Atlantic Ocean to expand. TheWestern Interior Seawaydivided North America into eastern and western halves;AppalachiaandLaramidia.[4]India maintained a northward course towards Asia.[4]In the Southern Hemisphere, Australia andAntarcticaseem to have remained connected and began to drift away from Africa and South America.[4]Europe was an island chain.[4]Populating some of these islands were endemicdwarfdinosaur species.[4]

Vertebrate fauna[edit]

Non-avian dinosaurs[edit]

In the Late Cretaceous, thehadrosaurs,ankylosaurs,andceratopsiansexperienced success inAsiamerica(Western North America and eastern Asia).Tyrannosaursdominated the large predator niche in North America.[4]They were also present in Asia, although were usually smaller and more primitive than the North American varieties.[4]Pachycephalosaurswere also present in both North America and Asia.[4]Dromaeosauridsshared the same geographical distribution, and are well documented in both Mongolia and Western North America.[4]Additionallytherizinosaurs(known previously as segnosaurs) appear to have been in North America and Asia.Gondwanaheld a very different dinosaurian fauna, with most predators beingabelisauridsandcarcharodontosaurids;andtitanosaursbeing among the dominant herbivores.[4] Spinosauridswere also present during this time.[5]

Birds[edit]

Birds became increasingly common, diversifying in a variety ofenantiornitheandornithurineforms. EarlyNeornithessuch asVegavis[6]co-existed with forms as bizarre asYungavolucrisandAvisaurus.[7]Though mostly small, marineHesperornithesbecame relatively large and flightless, adapted to life in the open sea.[8]

Pterosaurs[edit]

Though primarily represented byazhdarchids,other forms likepteranodontids,tapejarids(CaiuajaraandBakonydraco),nyctosauridsand uncertain forms (Piksi,Navajodactylus) are also present. Historically, it has been assumed that pterosaurs were in decline due to competition with birds, but it appears that neither group overlapped significantly ecologically, nor is it particularly evident that a true systematic decline was ever in place, especially with the discovery of smaller pterosaur species.[9]

Mammals[edit]

Several oldmammalgroups began to disappear, with the lasteutriconodontsoccurring in theCampanianofNorth America.[10]In the northern hemisphere,cimolodont,multituberculates,metatheriansandeutherianswere the dominant mammals, with the former two groups being the most common mammals in North America. In the southern hemisphere there was instead a more complex fauna ofdryolestoids,gondwanatheresand other multituberculates and basaleutherians;monotremeswere presumably present, as was the last of theharamiyidans,Avashishta.

Mammals, though generally small, ranged into a variety of ecological niches, from carnivores (Deltatheroida), to mollusc-eater (Stagodontidae), toherbivores(multituberculates,Schowalteria,ZhelestidaeandMesungulatidae) to highly atypical cursorial forms (Zalambdalestidae,Brandoniidae).[citation needed]

Trueplacentalsevolved only at the very end of the epoch; the same can be said for truemarsupials.Instead, nearly all known eutherian and metatherian fossils belong to other groups. [11]

Marine life[edit]

In the seas,mosasaurssuddenly appeared and underwent a spectacular evolutionary radiation. Modern sharks also appeared and penguin-likepolycotylidplesiosaurs(3 meters long) and huge long-neckedelasmosaurs(13 meters long) also diversified. These predators fed on the numerousteleostfishes, which in turn evolved into new advanced and modern forms (Neoteleostei).Ichthyosaursandpliosaurs,on the other hand, became extinct during theCenomanian-Turonian anoxic event.[citation needed]

Flora[edit]

Near the end of the Cretaceous Period,flowering plantsdiversified. In temperate regions, familiar plants likemagnolias,sassafras,roses,redwoods,andwillowscould be found in abundance.[4]

Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction discovery[edit]

The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event was a large-scalemass extinctionof animal and plant species in a geologically short period of time, approximately66million years ago(Ma). It is widely known as theK–T extinction eventand is associated with a geological signature, usually a thin band dated to that time and found in various parts of the world, known as theCretaceous–Paleogene boundary(K–T boundary).Kis the traditional abbreviation for the Cretaceous Period derived from the German nameKreidezeit,andTis the abbreviation for theTertiaryPeriod (a historical term for the period of time now covered by thePaleogeneandNeogeneperiods). The event marks the end of theMesozoicEra and the beginning of theCenozoicEra.[12]"Tertiary" being no longer recognized as a formal time or rock unit by theInternational Commission on Stratigraphy,the K-T event is now called the Cretaceous—Paleogene (or K-Pg) extinction event by many researchers.

Non-aviandinosaurfossilsare found only below the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary and became extinct immediately before or during the event.[13]A very small number ofdinosaurfossils have been found above the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, but they have been explained asreworked fossils,that is, fossils that have been eroded from their original locations then preserved in latersedimentarylayers.[14][15][16]Mosasaurs,plesiosaurs,pterosaursand manyspeciesof plants andinvertebratesalso became extinct.Mammalianand birdcladespassed through the boundary with few extinctions, andevolutionary radiationfrom thoseMaastrichtianclades occurred well past the boundary. Rates of extinction and radiation varied across different clades of organisms.[17]

Many scientists hypothesize that the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinctions were caused by catastrophic events such as the massiveasteroid impactthat caused theChicxulub crater,in combination with increasedvolcanic activity,such as that recorded in theDeccan Traps,both of which have been firmly dated to the time of the extinction event. In theory, these events reduced sunlight and hinderedphotosynthesis,leading to a massive disruption in Earth'secology.A much smaller number of researchers believe the extinction was more gradual, resulting from slower changes insea levelorclimate.[17]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^International Commission on Stratigraphy."ICS - Chart/Time Scale".stratigraphy.org.

- ^Kennedy, W.; Gale, A.; Lees, J.; Caron, M. (March 2004)."The Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Cenomanian Stage, Mont Risou, Hautes-Alpes, France"(PDF).Episodes.27:21–32.doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2004/v27i1/003.Retrieved13 December2020.

- ^ "Cretaceous Period | Definition, Climate, Dinosaurs, & Map".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2022-07-25.

- ^abcdefghijklm"Dinosaurs Ruled the World: Late Cretaceous Period." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B.The Age of Dinosaurs.Publications International, LTD. Pp. 103-104.ISBN0-7853-0443-6.

- ^Churcher, C. S; De Iuliis, G (2001)."A new species of Protopterus and a revision of Ceratodus humei (Dipnoi: Ceratodontiformes) from the Late Cretaceous Mut Formation of eastern Dakhleh Oasis, Western Desert of Egypt".Palaeontology.44(2): 305–323.Bibcode:2001Palgy..44..305C.doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00181.

- ^Clarke, J.A.; Tambussi, C.P.; Noriega, J.I.; Erickson, G.M.; Ketcham, R.A. (2005)."Definitive fossil evidence for the extant avian radiation in the Cretaceous"(PDF).Nature.433(7023): 305–308.Bibcode:2005Natur.433..305C.doi:10.1038/nature03150.hdl:11336/80763.PMID15662422.S2CID4354309.Supporting information

- ^Cyril A. Walker & Gareth J. Dyke (2009)."Euenantiornithine birds from the Late Cretaceous of El Brete (Argentina)"(PDF).Irish Journal of Earth Sciences.27:15–62.doi:10.3318/IJES.2010.27.15.S2CID129573066.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2012-03-20.

- ^Larry D. Martin; Evgeny N. Kurochkin; Tim T. Tokaryk (2012). "A new evolutionary lineage of diving birds from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia".Palaeoworld.21:59–63.doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2012.02.005.

- ^Prondvai, E.; Bodor, E. R.; Ösi, A. (2014)."Does morphology reflect osteohistology-based ontogeny? A case study of Late Cretaceous pterosaur jaw symphyses from Hungary reveals hidden taxonomic diversity"(PDF).Paleobiology.40(2): 288–321.Bibcode:2014Pbio...40..288P.doi:10.1666/13030.S2CID85673254.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on July 20, 2023.

- ^Fox Richard C (1969). "Studies of Late Cretaceous vertebrates. III. A triconodont mammal from Alberta".Canadian Journal of Zoology.47(6): 1253–1256.doi:10.1139/z69-196.

- ^Halliday Thomas J. D. (2015)."Resolving the relationships of Paleocene placental mammals"(PDF).Biological Reviews.92(1): 521–550.doi:10.1111/brv.12242.PMC6849585.PMID28075073.

- ^Fortey R (1999).Life: A Natural History of the First Four Billion Years of Life on Earth.Vintage. pp. 238–260.ISBN978-0375702617.

- ^Fastovsky DE, Sheehan PM (2005). "The extinction of the dinosaurs in North America".GSA Today.15(3): 4–10.doi:10.1130/1052-5173(2005)015<4:TEOTDI>2.0.CO;2.

- ^Sloan RE; Rigby K; Van Valen LM; Gabriel Diane (1986). "Gradual dinosaur extinction and simultaneous ungulate radiation in the Hell Creek formation".Science.232(4750): 629–633.Bibcode:1986Sci...232..629S.doi:10.1126/science.232.4750.629.PMID17781415.S2CID31638639.

- ^Fassett JE, Lucas SG, Zielinski RA, Budahn JR (9–12 July 2000).Compelling new evidence for Paleocene dinosaurs in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone San Juan Basin, New Mexico and Colorado, USA(PDF).International Conference on Catastrophic Events and Mass Extinctions: Impacts and Beyond. Vol. 1053. Vienna, Austria. pp. 45–46.

- ^Sullivan RM (May 8, 2003).No Paleocene dinosaurs in the San Juan Basin, New Mexico.Geological Society of America Rocky Mountain - 55th Annual Meeting.Vol. 35, no. 5. p. 15. Archived fromthe originalon 17 June 2007.

- ^abMacLeod N, Rawson PF, Forey PL, Banner FT, Boudagher-Fadel MK, Bown PR, Burnett JA, Chambers, P, Culver S, Evans SE, Jeffery C, Kaminski MA, Lord AR, Milner AC, Milner AR, Morris N, Owen E, Rosen BR, Smith AB, Taylor PD, Urquhart E, Young JR (1997). "The Cretaceous–Tertiary biotic transition".Journal of the Geological Society.154(2): 265–292.Bibcode:1997JGSoc.154..265M.doi:10.1144/gsjgs.154.2.0265.S2CID129654916.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)