Palace of Justice, Brussels

| Palace of Justice of Brussels | |

|---|---|

View of the Palace of Justice fromThe Hotel Brussels(thenHilton) in 2009 | |

| |

| Alternative names | Law Courts of Brussels |

| General information | |

| Type | Courthouse |

| Architectural style | |

| Address | Place Poelaert/Poelaertplein1 |

| Town or city | 1000City of Brussels,Brussels-Capital Region |

| Country | Belgium |

| Coordinates | 50°50′12″N4°21′06″E/ 50.83667°N 4.35167°E |

| Current tenants | Belgian courts |

| Construction started | 31 October 1866 |

| Inaugurated | 15 October 1883 |

| Renovated |

|

| Cost | 50 millionBelgian francs[a] |

| Client | Belgian Government |

| Owner | Belgian Government |

| Height | 116 m (381 ft)[1] |

| Dimensions | |

| Diameter | 160 m × 150 m (520 ft × 490 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 26,000 m2(280,000 sq ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Other designers | François Wellens |

| Designations | Protected (03/05/2001) |

| Other information | |

| Public transit access |

|

| Website | |

| Official website | |

| References | |

| [2] | |

ThePalace of Justice of Brussels(French:Palais de Justice de Bruxelles,pronounced[pa.lɛd(ə)ʒys.tisdəbʁy.sɛl];Dutch:) orLaw Courts of Brussels[b]is acourthouseinBrussels,Belgium. It is the country's most important court building, seat of thejudicialarrondissementof Brussels, as well as of severalcourts and tribunals,including theCourt of Cassation(Belgiansupreme court), theCourt of Assizes(highestcriminal court), theCourt of Appealof Brussels (appellate court), theTribunal of First Instanceof Brussels (general jurisdiction), and the Bar Association of Brussels.

Designed by the architectJoseph Poelaert,in aneclecticstyle ofGreco-Romaninspiration, to replace an older courthouse,[3]the current building was erected between 1866 and 1883. With a ground surface of 26,006 m2(279,930 sq ft), the edifice is reputed to be the largest constructed in the 19th century and remains one of the largest of its kind.[4]The total cost of the construction, land, and furnishings approximated 50 millionBelgian francs.[5][a]The building suffered heavy damage duringWorld War II,when thecupolawas destroyed and later rebuilt higher than the original. The structure has been under renovation since 1984 and scaffolding from that era still hangs on the building, though it is set to come down in 2024.[6]

The Palace of Justice is located on thePlace Poelaert/Poelaertpleinin theMarolles/Marollendistrict (southern part ofBrussels' city centre). A notable landmark of Brussels, this site is served byLouise/Louiza metro station(on lines2and6of theBrussels Metro), as well as thehomonymoustramstop (on lines 8 and 92).[7][8]From the lower part of town, it is also possible to take the publicPoelaert Elevatorsup to the square.[9]

History

[edit]First courthouse (1818–1892)

[edit]The current Palace of Justice is located on theGalgenberghill (French:Mont aux potences;"Gallows Mount" ), between Brussels' upper and lower town, where in theMiddle Agesconvicted criminals were hanged, hence its name.[10]A firstcourthousehad been erected, at a different location, in theSablon/Zaveldistrict, on thePlace du Palais/Paleisplein(today'sPlace de la Justice/Gerechtsplein), between theRue de l'Empereur/Keizerstraat(today'sBoulevard de l'Empereur/Keizerlaan) and the (now-disappeared)Rue d'Or/Guldenstraat.[11]

Built between 1818 and 1823 by the French architectFrançois Verlyon the site of a formerJesuitchurch,[12]this firstneoclassicalstructure had quickly deteriorated, and the question of building a new and larger courthouse arose as early as 1837. The condition was that the building could accommodate all civil and military jurisdictions under one roof.[3]The choice of location, however, gave rise to heated controversies. It was indeed initially planned to rebuild it in the same place, but this project, the cost of which was estimated at 3 millionBelgian francs,[c]quickly aborted.[13]The idea of building it in the newly developedLeopold Quarterin the eastern part of town was no more successful. In 1846–47, another reconstruction project was also buried.

-

The former Palace of Justice (Verly, 1823) on thePlace du Palais/Paleisplein

-

Beginning of the former Palace of Justice's demolition (1892)

-

Demolition in progress and construction of theRue Lebeau/Lebeaustraat(1892)

Inception of the project (1858–1866)

[edit]In 1858, the then-Minister of Justice,Victor Tesch,suggested for the first time the gardens of theHouse of Merode,where the extension of theRue de la Régence/Regentschapsstraatwould be constructed. Thegovernor of the Province of Brabantsuggested that it would be possible at the same time to link the newLouise/Louiza districtto thecity centre.Following a proposal from the advisor to theCourt of Appeal,Gustave Bosquet,aiming at installing the building perpendicular to the Rue de la Régence rather than to the right of this extension,[14]a study was entrusted to the Chief Engineer Groetaers. In his report, Groetaers recommended to erect a building of 26,000 m2(280,000 sq ft), with a 100 m (330 ft) fronting facing a 100 m square. Disagreements having arisen between Groetaers and thecity's mayor,the latter called for a competition for the building's design.[15]

On 27 March 1860, an international architectural competition, endowed with three prizes, was therefore organised byroyal decree.[16]After several failed proposals, Tesch appointed the city's municipal architect,Joseph Poelaert,to draw plans of the building in 1861.[17]The architect already enjoyed an excellent reputation, having to his credit a series of very prestigious projects in the capital, such as the commemorativeCongress Column(1850), the Church of St. Catherine (1854) and the restoration of theRoyal Theatre of La Monnaie(1855).[18]

In April 1862, Poelaert submitted a preliminary draft, which was approved by Tesch. It was then in Paris, far from the pressures and influences of Brussels, that Poelaert withdrew to put the final touches to his plans. There, he gathered a team of designers includingCharles LaisnéandÉdouard Corroyer.Given the prominent place that the Palace of Justice was called upon to occupy in the urban landscape, Poelaert opted for aneclecticstyle ofGreco-Romaninspiration. Although he was inspired by classicism, he created a totally personal and original work.[3]

Construction (1866–1883)

[edit]The first stone was laid on 31 October 1866.[19]At Poelaert's request, the management of the works was entrusted to the engineerFrançois Wellens,Inspector General of the Ministry of Public Works and President of the Royal Commission of Monuments between 1865 and 1897.[20][18]After Poelaert's death on 3 November 1879, the construction was taken over by the architect Joseph Joachim Benoît.[18]The building was inaugurated on 15 October 1883 byKing Leopold IIin the presence of his wifeQueen Marie-Henriette,his daughterPrincess Clémentine,and members of theBelgian royal family.[21][4]As for the old courthouse, it was demolished in 1892 for the construction of theRue Lebeau/Lebeaustraat,which leads into the Place de la Justice.[22]

For the Palace of Justice's construction, a section of theMarolles/Marollenneighbourhood was demolished, while most of the garden belonging to the House of Merode was also expropriated.[23]The 75 landlords belonging to thenobilityand thehigh bourgeoisie,many of whom lived in their homes,[24]received large indemnities, while the other more modest inhabitants, about a hundred, were also forced to move by theBelgian Government,though they were compensated with houses in theTillens-Roosendaelgarden city(French:cité-jardin Tillens-Roosendael) in theQuartier du Chatin theUcclemunicipality.[25]

Poelaert himself resided in the Marolles, only a few hundred metres from the building, on theRue des Minimes/Minimenstraat,in a house adjoining his vast offices and workshops and communicating with them.[26][27]It is thus unlikely he saw himself as ruining the neighbourhood. Nonetheless, many angry citizens personally blamed Poelaert for the forced relocations, and the expressionschieven architect(meaning "shameful architect" ) became one of the most serious insults in thedialect of the Marolles.[10]Although the construction took place during the reign of Leopold II, the king showed little interest in the building, and it is not considered part of his extensive architectural programme in Brussels nor his legacy as the "Builder-King".[28][29]

-

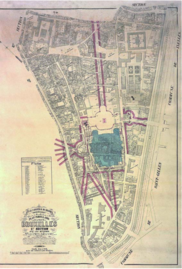

Development plan (1866)

-

Groundwork (1867)

-

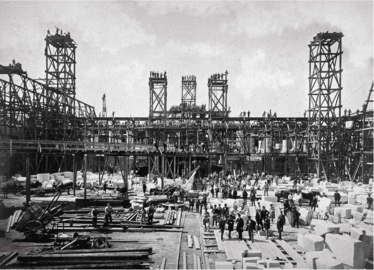

Assemblage of the scaffolding (1875)

-

Last stone laying (1882)

Damage and renovation (1945–present)

[edit]

At the end of theSecond World War,on the eve of theliberation of Brussels,the retreatingGerman forcesstarted a fire in the Palace of Justice in order to destroy it, as well as the legal records it contained. As a result, thecupolacollapsed and part of the building was heavily damaged. The explosion of aV-1 rocketin the Rue des Minimes two months later caused additional damage.[30]In 1947, the restoration work was entrusted to the architect-engineer and custodian of the Palace,Albert Storrer.[31][32]By 1948, most of the building was repaired, and the cupola was rebuilt 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) higher than the original, whose somewhat flat shape had previously been criticised.[33]

Renovations on the building have been in progress since 1984.[34]These renovations pertain to the repair and strengthening of the roof structure and the walls, as well as putting a new layer on thegildedcupola. In 2002–03, the roofing was renewed and the structural structure was repaired and reinforced. On 1 September 2003, the protective foil was removed from the dome, thus becoming once again an eye-catcher in the skyline of Brussels.[35]Progress is slow, however, and in 2013, it was reported that the decade-oldscaffoldingwas so rusted and unsafe that the scaffolding itself was in need of renovation.[36]

Since the end of the 20th century, many jurisdictions have successively left the Palace of Justice on the grounds that it no longer meets the criteria required for the exercise of contemporary justice, particularly in terms of the required workspace. TheGovernment of the Brussels-Capital Regionended up issuing two designations orders, on 3 May 2001 and on 28 February 2008, "Because of its historical, artistic and technical interest". In 2008, a proposal was made for the building's recognition as aWorld Heritage SitebyUNESCO.[4]In 2016, theWorld Monuments Fundplaced the courthouse on its list of endangered monuments.[37]In 2018, following the collapse of part of the ceiling, Jean de Codt, first president of the Court of Cassation and highestmagistratein the country, spoke openly in the media to demand additional financial resources to ensure the building's sustainability and the safety of those who work there.[38]Several plans have followed to find solutions to the dilapidated rooms and to security problems, but the work is expected to last for many more years, leaving the building's future uncertain. As of 2022, additional renovation plans have been announced, with completion expected now for "2024 or 2025".[39]

Dimensions

[edit]Brussels' Palace of Justice was, at the time of its construction, thelargest building in the world,and remains today one of the largest courthouses.[4][d]The edifice is currently 160 by 150 metres (520 by 490 ft),[4]and has a total built ground surface of 26,006 m2(279,930 sq ft),[40]bigger thanSt. Peter's BasilicainRome.The 105-metre-high (344 ft)domeweighs 24,000 tonnes (53,000,000 lb).[41]The building has 8 courtyards with a surface of 6,000 m2(65,000 sq ft), 27 large court rooms and 245 smaller court rooms and other rooms. Situated on a hill with a steep incline, there is a level difference of 20 metres (66 ft) between the upper and lower town,[42]which results in multiple entrances to the building at different levels.

The building includes huge interior statues ofDemosthenesandLycurgusby the sculptorPierre Armand Cattier,and figures of the Roman juristsCiceroandUlpianbyAntoine-Félix Bouré.[43]The central portico, 39 metres (128 ft) high, is surmounted by a helmetedbustof theancient Greek TitanessThemis,personificationof divine law and order, byJoseph Ducaju.[44]Moreover, the impressive main hall orsalle des pas perdus(lit. 'room of the lost steps') is around 3,600 m2(39,000 sq ft) including the first floor gallery: 90 metres (300 ft) long and 40 metres (130 ft) wide. Acompass rosewith sixteen rays marks the centre of the room.[45]

Many questions remain on this project, which saw its budget exceed 50 millionBelgian francs[5][a](which was equivalent to an entire year of public works in the country at the time) for an initial estimate of barely 4 million.[e]The excessiveness of the site, and the freedom left to the architect to override almost all the rules initially imposed, remain a great mystery.

-

The monumental marble staircase

-

The main entry hall orsalle des pas perdus

-

Interior view of thesalle des pas perdus

-

One of the massiveneoclassicaldoors

-

At the centre of the building looking upwards towards the dome

Usage

[edit]The Palace of Justice is the most important court building in Belgium, seat of the country's differentcourts and tribunals,most notably theCourt of Cassation,itssupreme court.The Court of Cassation handles cases in the two mainlanguages of Belgium,being Dutch and French, and provides certain facilities for cases in German. TheCourt of Assizes(criminal courtthat tries the most serious crimes), theCourt of Appealof Brussels (appellate court), as well as theTribunal of First Instanceof Brussels (general jurisdiction), also seat there. The Palace of Justice also includes within it the prosecution services adjoining these jurisdictions, as well as various libraries.[46]

Courts and tribunals

[edit]- Court of Cassation: 1st president, Griffie-Clerck and Prosecution

- Court of Assizes

- Court of Appeal of Brussels: 1st president, Griffie-Clerck and Prosecution

- Tribunal of First Instance of Brussels

Libraries

[edit]- Library of the Magistrate

- Library of the Bar Association of Brussels

- Library of the Lawyers

Arrondissement of Brussels

[edit]Moreover, the Palace of Justice is the seat of thejudicialarrondissementof Brussels (covering the entireBrussels-Capital Region), having split from theFlemishpart of the former bilingualarrondissementofBrussels-Halle-Vilvoorde(BHV) in mid-2012 (which madeHalle-Vilvoordea monolingual Flemish electoral and judicial district).[46]

Bar Association of Brussels

[edit]Finally, the Palace of Justice is also home to the Bar Association of Brussels (French:Barreau de Bruxelles,Dutch:Balie te Brussel), a professional order of 7,000 Brussels lawyers, founded on 14 December 1810. Since 1984, the Bar Association of Brussels has been split into two, the French-speaking order (Ordre français des Avocats du Barreau de Bruxelles)[47]and the Dutch-speaking order (Nederlandse Orde van Advocaten te Brussel).[48]

-

Standardcourtroomof theCourt of Cassationin the Palace of Justice

-

Old image of the Court's grand courtroom, used for larger sessions and judicial ceremonies

-

Logo of the Bar Association of Brussels (French-speaking order)

Surroundings

[edit]ThePlace Poelaert/Poelaertplein,in front of the Palace of Justice, is the largest square in Brussels, measuring 155 by 50 metres (509 by 164 ft). The initial development project, which provided for a large square in a semicircle (1862), could not be implemented due to Poelaert's sudden death. Consequently, this square does not have an architectural unity in the buildings that surrounds it, nor thebelvederecoming from the original plan, and instead constitutes a vast transit space unsuitable for pedestrians, not functioning as an urban square but as aroundaboutfor cars preventing the appropriation of the place by walkers. In 1905, it was the scene of prestigious commemorations for the 75th anniversary ofBelgian independence.[49]Nowadays, it offers one of Brussels' finest views. From the elevated vantage point, the famous tower ofBrussels' Town Hallon theGrand-Place/Grote Marktis clearly visible. On a sunny day, theKoekelberg Basilicaand even theAtomiumcan be seen.

Next to the Palace of Justice, on the Place Poelaert, stand twowar memorials:theBelgian Infantry MemorialbyEdouard Vereycken(1935) and theAnglo-Belgian MemorialbyCharles Sargeant Jagger(1923). In addition, thePoelaert Elevators,[50]in popular language the Elevators of the Marolles,[51][52][53]are a set of two publicelevatorsthat connects the upper and lower town between the Place Poelaert and theSquare Breughel l'Ancien/Breughel de Oudeplein.They were executed by the AVA Architects office, under the coordination of the architect Patrice Neirinck, and were inaugurated in June 2002.

-

ThePlace Poelaert/Poelaertpleinseen from the stairs of the Palace of Justice

-

Poelaert Elevators(Neirinck, 2002)

Influence

[edit]

There is a well-known story thatAdolf Hitlerwas reportedly fond of the building.Albert Speer,the Minister of Armaments and War Production inNazi Germany,stated in his bookInside the Third Reichthat he had been dispatched to Brussels in 1940 to study the building.[54]

Although lacking the dome and being much smaller, thePalace of JusticeinLima,Peru, which houses theSupreme Court of Peru,is based upon Brussels' Palace of Justice.[55]

In popular culture

[edit]Books

[edit]- The Palace of Justice is represented in the albumThe Last Pharaoh,published in 2019, from thecomic stripseriesBlake and Mortimer,in which it plays a central place of the plot.[56]

See also

[edit]- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- Neoclassical architecture in Belgium

- History of Brussels

- Belgium in the long nineteenth century

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^abcThis amount is roughly equivalent to €317 million in 2020 when taking into accountinflation.

- ^French:Cour de Justice de Bruxelles;Dutch:Rechtbank van Brussel

- ^Equivalent to €20 million in 2020 when taking into account inflation.

- ^It was not until 1965 that it was surpassed as the largest building in the world byNASA'sVehicle Assembly Building(VAB) atCape Canaveral.

- ^Equivalent to €25 million in 2020 when taking into account inflation.

Citations

[edit]- ^https://whc.unesco.org/fr/listesindicatives/5357/UNESCOWHS

- ^Région de Bruxelles-Capitale (2016)."Palais de Justice"(in French). Brussels.Retrieved12 January2022.

- ^abcVandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 24.

- ^abcdeCentre, UNESCO World Heritage."Le Palais de Justice de Bruxelles - UNESCO World Heritage Centre".whc.unesco.org.Retrieved20 May2018.

- ^abVandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 42.

- ^The Brussels Times (18 February 2023)."The unfathomable scale of justice".brusselstimes.Retrieved18 February2023.

- ^"Line 8 to ROODEBEEK - STIB Mobile".m.stib.be.Retrieved8 January2022.

- ^"Line 92 to FORT-JACO - STIB Mobile".m.stib.be.Retrieved8 January2022.

- ^"Palais de Justice, Brussels - Opening hours, tickets and location".introducingbrussels.Retrieved28 October2019.

- ^ab"Palais de Justice"(in French). Belgian federal building registry. 29 September 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 24 February 2011.Retrieved12 August2009.

- ^"Place de la Justice".reflexcity.net.Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^Snaet & Van Besien 2012,p. 78.

- ^Vandendaele & Leblicq 1980,p. 251–260.

- ^Vandendaele & Leblicq 1980,p. 263.

- ^Vandendaele & Leblicq 1980,p. 268.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 14.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 15.

- ^abcSnaet & Van Besien 2012,p. 79.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 20.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 25–26.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 32.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 11.

- ^Vandendaele & Leblicq 1980,p. 270.

- ^Vandendaele & Leblicq 1980,p. 166:Plan du géomètre Van Keerbergen indiquant les propriétés nécessaires à l'érection du Palais de Justice de Poelaert, 9 février 1863 (A.V.B., T.P., 26.242).

- ^Quiévreux 1951,p. 257.

- ^Vandendaele & Leblicq 1980,p. 166.

- ^Mardaga 1994,p. 466.

- ^Emerson 1980,p. 264.

- ^Demey 2009,p. 172.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 33.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 34–35.

- ^Demey 2009,p. 187.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 35.

- ^"Bruxelles redécouvre son palais de justice".Luxemburger Wort - Edition francophone(in French). 8 August 2019.Retrieved29 October2021.

- ^Sports+, DH Les (30 August 2003)."La coupole du Palais de Justice à nouveau blinquante".DH Les Sports +(in French).Retrieved13 January2022.

- ^"Stellingen Brussels justitiepaleis zelf aan restauratie toe"(in Dutch).De Standaard.30 November 2013.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"Brussels Palace of Justice".World Monuments Fund.Retrieved29 October2021.

- ^"Délabrement du palais de justice:" désinvestissement "et" désorganisation "selon Jean de Codt".RTBF Info(in French). 6 September 2018.Retrieved29 October2021.

- ^The Brussels Times (2 May 2022)."Brussels Justice Palace renovation delayed again as 15% of bricks must be replaced".brusselstimes.Retrieved2 May2022.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 21.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 28.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 41.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 35–36.

- ^Van Win 2012,p. 272–273.

- ^Vandenbreeden & Loits 2001,p. 38.

- ^ab"Judiciary – Organization"(PDF).dekamer.be.Parliamentary information sheet № 22.00.Belgian Chamber of Representatives.1 June 2014.Retrieved8 November2020.

- ^"Home".Barreau de Bruxelles(in French).Retrieved13 January2022.

- ^"Home".Balie Brussel(in Dutch).Retrieved13 January2022.

- ^Bournons 2009,p. 34.

- ^"Constructie van de Poelaertliften".Beliris(in Dutch).Retrieved19 June2021.

- ^"Bruxelles La passerelle de l'ascenseur des Marolles est arrivée samedi Réconcilier le haut et le bas de la ville MODE D'EMPLOI".Le Soir Plus(in French).Retrieved19 June2021.

- ^"Les ascenseurs des Marolles seront rénovés en 2021".BX1(in French). 7 July 2020.Retrieved19 June2021.

- ^"Lift Marollen in nieuw kleedje".bruzz.be(in Dutch).Retrieved19 June2021.

- ^Speer 1995,p. 42.

- ^"A PALACE FOR JUSTICE – A never-ending Belgian story".4 November 2022.

- ^"Palais de Justice (Rue de la Régence, Palais de Justice, François Schuiten, Le Dernier Pharaon)".reflexcity.net.Retrieved7 November2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bournons, Éric (2009).Bruxelles d'Antan. Bruxelles à travers la carte postale ancienne(in French). Paris: HC Éditions.ISBN978-2-357-20017-3.

- Debes, Ilona Andrea (2021).Der vergessene Löwe - Anmerkungen zu einer Löwenfigur von Léandre Grandmoulin im Justizpalast von Brüssel in: "Mit Belgien ist das so eine Sache..." - Resultate und Perspektiven der Historischen Belgienforschung(in German). Münster: Waxmann Verlag.ISBN978-3-8309-4317-4.

- Demey, Thierry (2009).Léopold II (1865-1909). La marque royale sur Bruxelles(in French). Brussels: Badeaux.ISBN978-2-9600414-8-4.

- Emerson, Barbara (1994).Léopold II, le royaume et l'empire(in French). Brussels: Duculot.

- Snaet, Joris; Van Besien, Elisabeth (2012).Le Palais de Justice de Bruxelles. Un tour de force monumental.Bruxelles Patrimoines (in French). Vol. 3–4. Brussels: Éditions de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale.

- Speer, Albert (1995).Inside the Third Reich.R. and C. Winston (trans.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.ISBN978-1-84212-735-3.

- Quiévreux, Louis (1951).Bruxelles, notre capitale: histoire, folklore, archéologie(in French). Brussels: PIM-Services.

- Vandenbreeden, Jos; Loits, André (2001).Le Palais de Justice.Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). Vol. 31. Brussels: Éditions de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale.ISBN978-2-930457-78-9.

- Vandendaele, Richard; Leblicq, Yvon (1980).Poelaert et son temps (exhibition catalogue)(in French). Brussels: Crédit Communal de Belgique.

- Van Win, Jean (2012).Bruxelles maçonnique. Faux mystères et vrais symboles(in French). Brussels: Télélivre.ISBN978-2-930331-09-6.

- Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique: Bruxelles(PDF)(in French). Vol. 1C: Pentagone N-Z. Liège: Pierre Mardaga. 1994.

External links

[edit] Media related toPalace of Justice, Brusselsat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toPalace of Justice, Brusselsat Wikimedia Commons- Climbing the Law Courts

- (in Dutch)Justitiepaleisor(in French)Palais de justice