Lichen

Alichen(/ˈlaɪkən/LY-kən,UKalso/ˈlɪtʃən/LITCH-ən) is a hybridcolonyofalgaeorcyanobacterialivingsymbioticallyamongfilamentsof multiplefungispecies, along with ayeastembedded in the cortex or "skin", in amutualisticrelationship.[1][2][obsolete source][3][obsolete source][4][obsolete source][5]

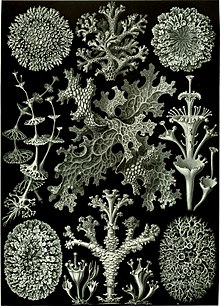

Lichens are important actors innutrient cyclingand act as producers which many higher trophic feeders feed on, such as reindeer, gastropods, nematodes, mites, and springtails.[6][7][8][9]Lichens have properties different from those of their component organisms. They come in many colors, sizes, and forms and are sometimes plant-like, but are notplants.They may have tiny, leafless branches (fruticose); flat leaf-like structures (foliose); grow crust-like, adhering tightly to a surface (substrate) like a thick coat of paint (crustose);[10]have a powder-like appearance (leprose); or othergrowth forms.[11]

Amacrolichenis a lichen that is either bush-like or leafy; all other lichens are termedmicrolichens.[2]Here, "macro" and "micro" do not refer to size, but to the growth form.[2]Common names for lichensmay contain the wordmoss(e.g., "reindeer moss","Iceland moss"), and lichens may superficially look like and grow withmosses,but they are not closely related to mosses or any plant.[4]: 3 Lichens do not have roots that absorb water and nutrients as plants do,[12]: 2 but like plants, they produce their own nutrition byphotosynthesis.[13]When they grow on plants, they do not live asparasites,but instead use the plant's surface as a substrate.

Lichens occur fromsea levelto highalpineelevations, in many environmental conditions, and can grow on almost any surface.[13][14]They are abundant growing on bark,leaves,mosses, or other lichens[12]and hanging from branches "living on thin air" (epiphytes) inrainforestsand intemperate woodland.They grow on rock, walls,gravestones,roofs,exposed soil surfaces, rubber, bones, and in the soil as part ofbiological soil crusts.Various lichens have adapted to survive in some of the most extreme environments on Earth:arctic tundra,hot drydeserts,rocky coasts,and toxicslagheaps. They can even live inside solid rock, growing between the grains (endolithic).

There are about 20,000 known species.[15]Some lichenshave lost the ability to reproduce sexually, yet continue tospeciate.[12][16]They can be seen as being relatively self-contained miniatureecosystems,where the fungi, algae, or cyanobacteria have the potential to engage with othermicroorganismsin a functioning system that may evolve as an even more complexcomposite organism.[17][18][19][20]Lichens may belong-lived,with some considered to be among the oldest living things.[4][21]They are among the first living things to grow on fresh rock exposed after an event such as a landslide. The long life-span and slow and regular growth rate of some species can be used to date events (lichenometry). Lichens are akeystone speciesin many ecosystems and benefittreesandbirds.[22]

Etymology and pronunciation

[edit]The English wordlichenderives from theGreekλειχήνleichēn( "tree moss, lichen, lichen-like eruption on skin" ) viaLatinlichen.[23][24][25]The Greek noun, which literally means "licker", derives from the verbλείχεινleichein,"to lick".[26][27]In American English, "lichen" is pronounced the same as the verb "liken" (/ˈlaɪkən/). In British English, both this pronunciation and one rhyming with "kitchen" (/ˈlɪtʃən/) are used.[28][29][30]

Anatomy and morphology

[edit]Growth forms

[edit]Lichens grow in a wide range of shapes and forms; this external appearance is known as theirmorphology.The shape of a lichen is usually determined by the organization of the fungal filaments.[31]The nonreproductive tissues, or vegetative body parts, are called thethallus.Lichens are grouped by thallus type, since the thallus is usually the most visually prominent part of the lichen. Thallus growth forms typically correspond to a few basic internal structure types.Common names for lichensoften come from a growth form or color that is typical of a lichengenus.

Common groupings of lichen thallus growth forms are:

- fruticose[32][33][34]– growing like a tuft or multiple-branched leafless mini-shrub, upright or hanging down, 3-dimensional branches with nearly round cross section (terete) or flattened

- foliose[32][33]– growing in 2-dimensional, flat, leaf-like lobes

- crustose[10][32][33]– crust-like, adhering tightly to a surface (substrate) like a thick coat of paint

- squamulose[34]– formed of small leaf-like scales crustose below but free at the tips

- leprose[35]– powdery

- gelatinous– jelly-like

- filamentous– stringy or like matted hair

- byssoid– wispy, liketeased wool

- structureless

There are variations in growth types in a single lichen species, grey areas between the growth type descriptions, and overlapping between growth types, so some authors might describe lichens using different growth type descriptions.

When a crustose lichen gets old, the center may start to crack up like old-dried paint, old-broken asphalt paving, or like the polygonal "islands" of cracked-up mud in a dried lakebed. This is called beingrimoseorareolate,and the "island" pieces separated by the cracks are called areolas.[32]The areolas appear separated, but are (or were)[citation needed]connected by an underlyingprothallusorhypothallus.[35]When a crustose lichen grows from a center and appears to radiate out, it is called crustose placodioid. When the edges of the areolas lift up from the substrate, it is calledsquamulose.[36]: 159 [34]

These growth form groups are not precisely defined. Foliose lichens may sometimes branch and appear to be fruticose. Fruticose lichens may have flattened branching parts and appear leafy. Squamulose lichens may appear where the edges lift up. Gelatinous lichens may appear leafy when dry.[36]: 159

The thallus is not always the part of the lichen that is most visually noticeable. Some lichens can growinsidesolid rock between the grains (endolithic lichens), with only the sexual fruiting part visible growing outside the rock.[32]These may be dramatic in color or appearance.[32]Forms of these sexual parts are not in the above growth form categories.[32]The most visually noticeable reproductive parts are often circular, raised, plate-like or disc-like outgrowths, with crinkly edges, and are described in sections below.

Color

[edit]

Lichens come in many colors.[12]: 4 Coloration is usually determined by the photosynthetic component.[31]Special pigments, such as yellowusnic acid,give lichens a variety of colors, including reds, oranges, yellows, and browns, especially in exposed, dry habitats.[37]In the absence of special pigments, lichens are usually bright green to olive gray when wet, gray or grayish-green to brown when dry.[37]This is because moisture causes the surface skin (cortex) to become more transparent, exposing the green photobiont layer.[37]Different colored lichens covering large areas of exposed rock surfaces, or lichens covering or hanging from bark can be a spectacular display when the patches of diverse colors "come to life" or "glow" in brilliant displays following rain.

Different colored lichens may inhabit different adjacent sections of a rock face, depending on the angle of exposure to light.[37]Colonies of lichens may be spectacular in appearance, dominating much of the surface of the visual landscape in forests and natural places, such as thevertical "paint"covering the vast rock faces ofYosemite National Park.[38]

Color is used in identification.[39]: 4 The color of a lichen changes depending on whether the lichen is wet or dry.[39]Color descriptions used for identification are based on the color that shows when the lichen is dry.[39]Dry lichens with a cyanobacterium as the photosynthetic partner tend to be dark grey, brown, or black.[39]

The underside of the leaf-like lobes of foliose lichens is a different color from the top side (dorsiventral), often brown or black, sometimes white. A fruticose lichen may have flattened "branches", appearing similar to a foliose lichen, but the underside of a leaf-like structure on a fruticose lichen is thesamecolor as the top side. The leaf-like lobes of a foliose lichen may branch, giving the appearance of a fruticose lichen, but the underside will be adifferentcolor from the top side.[35]

The sheen on some jelly-like gelatinous lichens is created bymucilaginoussecretions.[31]

Internal structure

[edit]

(a) Thecortexis the outer layer of tightly woven fungus filaments (hyphae)

(b) This photobiont layer has photosynthesizinggreen algae

(c) Loosely packed hyphae in the medulla

(d) A tightly woven lower cortex

(e) Anchoring hyphae calledrhizineswhere the fungus attaches to the substrate

A lichen consists of a simple photosynthesizing organism, usually agreen algaorcyanobacterium,surrounded by filaments of a fungus. Generally, most of a lichen's bulk is made of interwoven fungal filaments,[40]but this is reversed in filamentous and gelatinous lichens.[31]The fungus is called amycobiont.The photosynthesizing organism is called aphotobiont.Algal photobionts are calledphycobionts.[41]Cyanobacteria photobionts are calledcyanobionts.[41]

The part of a lichen that is not involved in reproduction, the "body" or "vegetative tissue" of a lichen, is called thethallus.The thallus form is very different from any form where the fungus or alga are growing separately. The thallus is made up of filaments of the fungus calledhyphae.The filaments grow by branching then rejoining to create a mesh, which is called being "anastomosed".The mesh of fungal filaments may be dense or loose.

Generally, the fungal mesh surrounds the algal orcyanobacterialcells, often enclosing them within complex fungal tissues that are unique to lichen associations. The thallus may or may not have a protective "skin" of densely packed fungal filaments, often containing a second fungal species,[1]which is called acortex.Fruticose lichens have one cortex layer wrapping around the "branches". Foliose lichens have an upper cortex on the top side of the "leaf", and a separate lower cortex on the bottom side. Crustose and squamulose lichens have only an upper cortex, with the "inside" of the lichen in direct contact with the surface they grow on (thesubstrate). Even if the edges peel up from the substrate and appear flat and leaf-like, they lack a lower cortex, unlike foliose lichens. Filamentous, byssoid, leprose,[35]gelatinous, and other lichens do not have a cortex; in other words, they areecorticate.[42]

Fruticose, foliose, crustose, and squamulose lichens generally have up to three different types of tissue,differentiatedby having different densities of fungal filaments.[40]The top layer, where the lichen contacts the environment, is called acortex.[40]The cortex is made of densely tightly woven, packed, and glued together (agglutinated) fungal filaments.[40]The dense packing makes the cortex act like a protective "skin", keeping other organisms out, and reducing the intensity of sunlight on the layers below.[40]The cortex layer can be up to several hundred micrometers (μm) in thickness (less than a millimeter).[43]The cortex may be further topped by an epicortex of secretions, not cells, 0.6–1 μm thick insome lichens.[43]This secretion layer may or may not have pores.[43]

Below the cortex layer is a layer called thephotobiontic layerorsymbiont layer.[33][40]The symbiont layer has less densely packed fungal filaments, with the photosynthetic partner embedded in them.[40]The less dense packing allows air circulation during photosynthesis, similar to the anatomy of a leaf.[40]Each cell or group of cells of the photobiont is usually individually wrapped by hyphae, and in some cases penetrated by ahaustorium.[31]In crustose and foliose lichens, algae in the photobiontic layer are diffuse among the fungal filaments, decreasing in gradation into the layer below. In fruticose lichens, the photobiontic layer is sharply distinct from the layer below.[31]

The layer beneath the symbiont layer is called themedulla.The medulla is less densely packed with fungal filaments than the layers above. In foliose lichens, as inPeltigera,[36]: 159 there is usually another densely packed layer of fungal filaments called the lower cortex.[35][40]Root-like fungal structures calledrhizines(usually)[36]: 159 grow from the lower cortex to attach or anchor the lichen to the substrate.[2][35]Fruticose lichens have a single cortex wrapping all the way around the "stems" and "branches".[36]The medulla is the lowest layer, and may form a cottony white inner core for the branchlike thallus, or it may be hollow.[36]: 159 Crustose and squamulose lichens lack a lower cortex, and the medulla is in direct contact with thesubstratethat the lichen grows on.

In crustose areolate lichens, the edges of the areolas peel up from the substrate and appear leafy. In squamulose lichens the part of the lichen thallus that is not attached to the substrate may also appear leafy. But these leafy parts lack a lower cortex, which distinguishes crustose and squamulose lichens from foliose lichens.[40]Conversely, foliose lichens may appear flattened against the substrate like a crustose lichen, but most of the leaf-like lobes can be lifted up from the substrate because it is separated from it by a tightly packed lower cortex.[35]

Gelatinous,[36]: 159 byssoid, and leprose lichens lack a cortex (areecorticate), and generally have only undifferentiated tissue, similar to only having a symbiont layer.[citation needed]

In lichens that include both green algalandcyanobacterial symbionts, the cyanobacteria may be held on the upper or lower surface in small pustules calledcephalodia.

Pruiniais a whitish coating on top of an upper surface.[44]Anepinecral layeris "a layer of horny dead fungal hyphae with indistinctluminain or near the cortex above the algal layer ".[44]

In August 2016, it was reported that some macrolichens have more than one species of fungus in their tissues.[1]

Physiology

[edit]Symbiotic relation

[edit]Lichens are fungi that have discovered agriculture

— Trevor Goward[45]

A lichen is a composite organism that emerges fromalgaeorcyanobacterialiving among the filaments (hyphae) of thefungiin a mutually beneficialsymbioticrelationship. The fungi benefit from the carbohydrates produced by the algae or cyanobacteria viaphotosynthesis.The algae or cyanobacteria benefit by being protected from the environment by the filaments of the fungi, which also gather moisture and nutrients from the environment, and (usually) provide an anchor to it. Although some photosynthetic partners in a lichen can survive outside the lichen, the lichen symbiotic association extends the ecological range of both partners, whereby most descriptions of lichen associations describe them as symbiotic. Both partners gain water and mineral nutrients mainly from the atmosphere, through rain and dust. The fungal partner protects the alga by retaining water, serving as a larger capture area for mineral nutrients and, in some cases, provides minerals obtained from thesubstrate.If acyanobacteriumis present, as a primary partner or another symbiont in addition to a green alga as in certaintripartitelichens, they canfix atmospheric nitrogen,complementing the activities of the green alga.

In three different lineages the fungal partner has independently lost the mitochondrial gene atp9, which has key functions in mitochondrial energy production. The loss makes the fungi completely dependent on their symbionts.[46]

The algal or cyanobacterial cells arephotosyntheticand, as in plants, theyreduceatmosphericcarbon dioxideinto organic carbon sugars to feed both symbionts. Phycobionts (algae) producesugar alcohols(ribitol,sorbitol,anderythritol), which are absorbed by the mycobiont (fungus).[41]Cyanobionts produceglucose.[41]Lichenized fungal cells can make the photobiont "leak" out the products of photosynthesis, where they can then be absorbed by the fungus.[12]: 5

It appears many, probably the majority, of lichen also live in a symbiotic relationship with an order ofbasidiomyceteyeasts calledCyphobasidiales.The absence of this third partner could explain why growing lichen in the laboratory is difficult. The yeast cells are responsible for the formation of the characteristic cortex of the lichen thallus, and could also be important for its shape.[47]

The lichen combination of alga or cyanobacterium with a fungus has a very different form (morphology), physiology, and biochemistry than the component fungus, alga, or cyanobacterium growing by itself, naturally or in culture. The body (thallus) of most lichens is different from those of either the fungus or alga growing separately. When grown in the laboratory in the absence of its photobiont, a lichen fungus develops as a structureless, undifferentiated mass of fungal filaments (hyphae). If combined with its photobiont under appropriate conditions, its characteristic form associated with the photobiont emerges, in the process calledmorphogenesis.[4]In a few remarkable cases, a single lichen fungus can develop into two very different lichen forms when associating with either a green algal or a cyanobacterial symbiont. Quite naturally, these alternative forms were at first considered to be different species, until they were found growing in a conjoined manner.[citation needed]

Evidence that lichens are examples of successfulsymbiosisis the fact that lichens can be found in almost every habitat and geographic area on the planet.[17]Two species in two genera of green algae are found in over 35% of all lichens, but can only rarely be found living on their own outside of a lichen.[48]

In a case where one fungal partner simultaneously had two green algae partners that outperform each other in different climates, this might indicate having more than one photosynthetic partner at the same time might enable the lichen to exist in a wider range of habitats and geographic locations.[17]

At least one form of lichen, the North American beard-like lichens, are constituted of not two but three symbiotic partners: an ascomycetous fungus, a photosynthetic alga, and, unexpectedly, a basidiomycetous yeast.[49]

Phycobionts can have a net output of sugars with only water vapor.[41]The thallus must be saturated with liquid water for cyanobionts to photosynthesize.[41]

Algae produce sugars that are absorbed by the fungus by diffusion into special fungal hyphae calledappressoriaorhaustoriain contact with the wall of the algal cells.[50]The appressoria or haustoria may produce a substance that increases permeability of the algal cell walls, and may penetrate the walls.[50]The algae may contribute up to 80% of their sugar production to the fungus.[50]

Ecology

[edit]Lichen associations may be examples ofmutualismorcommensalism,but the lichen relationship can be consideredparasitic[51]under circumstances where the photosynthetic partner can exist in nature independently of the fungal partner, but not vice versa. Photobiont cells are routinely destroyed in the course ofnutrientexchange. The association continues because reproduction of the photobiont cells matches the rate at which they are destroyed.[51]Thefungussurrounds the algal cells,[13]often enclosing them within complex fungal tissues unique to lichen associations. In many species the fungus penetrates the algal cell wall,[13]forming penetration pegs (haustoria) similar to those produced bypathogenic fungithat feed on a host.[34][52]Cyanobacteriain laboratory settings can grow faster when they are alone rather than when they are part of a lichen.

Miniature ecosystem and holobiont theory

[edit]Symbiosis in lichens is so well-balanced that lichens have been considered to be relatively self-contained miniature ecosystems in and of themselves.[17][18]It is thought that lichens may be even more complex symbiotic systems that include non-photosynthetic bacterial communities performing other functions as partners in aholobiont.[19][20]

Many lichens are very sensitive to environmental disturbances and can be used to cheaply[13]assessair pollution,[53][54][55]ozonedepletion, and metal contamination. Lichens have been used in makingdyes,perfumes (oakmoss),[56]and intraditional medicines.A few lichen species are eaten by insects[13]or larger animals, such as reindeer.[57]Lichens are widely used as environmental indicators or bio-indicators. When air is very badly polluted with sulphur dioxide, there may be no lichens present; only some green algae can tolerate those conditions. If the air is clean, then shrubby, hairy and leafy lichens become abundant. A few lichen species can tolerate fairly high levels of pollution, and are commonly found in urban areas, on pavements, walls and tree bark. The most sensitive lichens are shrubby and leafy, while the most tolerant lichens are all crusty in appearance. Since industrialisation, many of the shrubby and leafy lichens such asRamalina,UsneaandLobariaspecies have very limited ranges, often being confined to the areas which have the cleanest air.

Lichenicolous fungi

[edit]Some fungi can only be found livingonlichens asobligate parasites.These are referred to aslichenicolous fungi,and are a different species from the fungus living inside the lichen; thus they are not considered to be part of the lichen.[58]

Reaction to water

[edit]Moisture makes the cortex become more transparent.[12]: 4 This way, the algae can conduct photosynthesis when moisture is available, and is protected at other times. When the cortex is more transparent, the algae show more clearly and the lichen looks greener.

Metabolites, metabolite structures and bioactivity

[edit]Lichens can show intense antioxidant activity.[59][60]Secondary metabolitesare often deposited as crystals in theapoplast.[61]Secondary metabolites are thought to play a role in preference for some substrates over others.[61]

Growth rate

[edit]Lichens often have a regular but very slow growth rate of less than a millimeter per year.

In crustose lichens, the area along the margin is where the most active growth is taking place.[36]: 159 Most crustose lichens grow only 1–2 mm in diameter per year.

Life span

[edit]Lichens may belong-lived,with some considered to be among the oldest living organisms.[4][21]Lifespan is difficult to measure because what defines the "same" individual lichen is not precise.[62]Lichens grow by vegetatively breaking off a piece, which may or may not be defined as the "same" lichen, and two lichens can merge, then becoming the "same" lichen.[62]One specimen ofRhizocarpon geographicumon EastBaffin Islandhas an estimated age of 9500 years.[63][64]ThalliofRhizocarpon geographicumandRhizocarponeupetraeoides/inarensein the centralBrooks Rangeof northern Alaska have been given a maximum possible age of 10,000–11,500 years.[65][66]

Response to environmental stress

[edit]Unlike simple dehydration in plants and animals, lichens may experience acompleteloss of body water in dry periods.[13]Lichens are capable of surviving extremely low levels ofwatercontent (poikilohydric).[67]: 5–6 They quickly absorb water when it becomes available again, becoming soft and fleshy.[13]

In tests, lichen survived and showed remarkable results on theadaptation capacityofphotosynthetic activitywithin thesimulation timeof 34 days underMartian conditionsin the Mars Simulation Laboratory (MSL) maintained by theGerman Aerospace Center(DLR).[68][69]

TheEuropean Space Agencyhas discovered that lichens can survive unprotected in space. In an experiment led by Leopoldo Sancho from the Complutense University of Madrid, two species of lichen—Rhizocarpon geographicumandRusavskia elegans—were sealed in a capsule and launched on a Russian Soyuz rocket 31 May 2005. Once in orbit, the capsules were opened and the lichens were directly exposed to the vacuum of space with its widely fluctuating temperatures and cosmic radiation. After 15 days, the lichens were brought back to earth and were found to be unchanged in their ability to photosynthesize.[70][71]

Reproduction and dispersal

[edit]Vegetative reproduction

[edit]

Many lichens reproduce asexually, either by a piece breaking off and growing on its own (vegetative reproduction) or through the dispersal ofdiasporescontaining a few algal cells surrounded by fungal cells.[2]Because of the relative lack of differentiation in the thallus, the line between diaspore formation and vegetative reproduction is often blurred. Fruticose lichens can fragment, and new lichens can grow from the fragment (vegetative reproduction). Many lichens break up into fragments when they dry, dispersing themselves by wind action, to resume growth when moisture returns.[72][73]Soredia(singular: "soredium" ) are small groups of algal cells surrounded by fungal filaments that form in structures called soralia, from which the soredia can be dispersed by wind.[2]Isidia(singular: "isidium" ) are branched, spiny, elongated, outgrowths from the thallus that break off for mechanical dispersal.[2]Lichen propagules (diaspores) typically contain cells from both partners, although the fungal components of so-called "fringe species" rely instead on algal cells dispersed by the "core species".[74]

Sexual reproduction

[edit]

Structures involved in reproduction often appear as discs, bumps, or squiggly lines on the surface of the thallus.[12]: 4 Though it has been argued that sexual reproduction in photobionts is selected against, there is strong evidence that suggests meiotic activities (sexual reproduction) inTrebouxia.[75][76]Many lichen fungi reproduce sexually like other fungi, producing spores formed bymeiosisand fusion of gametes. Following dispersal, such fungal spores must meet with a compatible algal partner before a functional lichen can form.

Some lichen fungi belong to the phylumBasidiomycota(basidiolichens) and producemushroom-like reproductive structures resembling those of their nonlichenized relatives.

Most lichen fungi belong toAscomycetes(ascolichens). Among the ascolichens,sporesare produced in spore-producing structures calledascomata.[12]The most common types of ascomata are theapothecium(plural: apothecia) andperithecium(plural: perithecia).[12]: 14 Apothecia are usually cups or plate-like discs located on the top surface of the lichen thallus. When apothecia are shaped like squiggly line segments instead of like discs, they are calledlirellae.[12]: 14 Perithecia are shaped like flasks that are immersed in the lichen thallus tissue, which has a small hole for the spores to escape the flask, and appear like black dots on the lichen surface.[12]: 14

The three most common spore body types are raised discs calledapothecia(singular: apothecium), bottle-like cups with a small hole at the top calledperithecia(singular: perithecium), andpycnidia(singular: pycnidium), shaped like perithecia but without asci (anascusis the structure that contains and releases the sexual spores in fungi of theAscomycota).[77]

The apothecium has a layer of exposed spore-producing cells calledasci(singular: ascus), and is usually a different color from the thallus tissue.[12]: 14 When the apothecium has an outer margin, the margin is called theexciple.[12]: 14 When the exciple has a color similar to colored thallus tissue the apothecium or lichen is calledlecanorine,meaning similar to members of the genusLecanora.[12]: 14 When the exciple is blackened like carbon it is calledlecideinemeaning similar to members of the genusLecidea.[12]: 14 When the margin is pale or colorless it is calledbiatorine.[12]: 14

A "podetium"(plural:podetia) is a lichenized stalk-like structure of the fruiting body rising from the thallus, associated with some fungi that produce a fungalapothecium.[33]Since it is part of the reproductive tissue, podetia are not considered part of the main body (thallus), but may be visually prominent.[33]The podetium may be branched, and sometimes cup-like. They usually bear the fungalpycnidiaorapotheciaor both.[33]Many lichens haveapotheciathat are visible to the naked eye.[2]

Most lichens produce abundant sexual structures.[78]Many species appear to disperse only by sexual spores.[78]For example, the crustose lichensGraphis scriptaandOchrolechia parellaproduce no symbiotic vegetative propagules. Instead, the lichen-forming fungi of these species reproduce sexually by self-fertilization (i.e. they arehomothallic). This breeding system may enable successful reproduction in harsh environments.[78]

Mazaedia(singular: mazaedium) are apothecia shaped like adressmaker's pininpin lichens,where the fruiting body is a brown or black mass of loose ascospores enclosed by a cup-shaped exciple, which sits on top of a tiny stalk.[12]: 15

Taxonomy and classification

[edit]Lichens are classified by the fungal component. Lichen species are given the same scientific name (binomial name) as the fungus species in the lichen. Lichens are being integrated into the classification schemes for fungi. The alga bears its own scientific name, which bears no relationship to that of the lichen or fungus.[79]There are about 20,000 identified lichen species,[80][81]and taxonomists have estimated that the total number of lichen species (including those yet undiscovered) might be as high as 28,000.[82]Nearly 20% of known fungal species are associated with lichens.[50]

"Lichenized fungus"may refer to the entire lichen, or to just the fungus. This may cause confusion without context. A particular fungus species may form lichens with different algae species, giving rise to what appear to be different lichen species, but which are still classified (as of 2014) as the same lichen species.[83]

Formerly, some lichen taxonomists placed lichens in their own division, theMycophycophyta,but this practice is no longer accepted because the components belong to separatelineages.Neither the ascolichens nor the basidiolichens formmonophyleticlineages in their respective fungal phyla, but they do form several major solely or primarily lichen-forming groups within each phylum.[84]Even more unusual than basidiolichens is the fungusGeosiphon pyriforme,a member of theGlomeromycotathat is unique in that it encloses a cyanobacterial symbiont inside its cells.Geosiphonis not usually considered to be a lichen, and its peculiar symbiosis was not recognized for many years. The genus is more closely allied toendomycorrhizalgenera. Fungi fromVerrucarialesalso form marine lichens with thebrown algaePetroderma maculiforme,[85]and have a symbiotic relationship withseaweed(such asrockweed) andBlidingia minima,where the algae are the dominant components. The fungi is thought to help the rockweeds to resist desiccation when exposed to air.[86][87]In addition, lichens can also useyellow-green algae(Heterococcus) as their symbiotic partner.[88]

Lichens independently emerged from fungi associating with algae and cyanobacteria multiple times throughout history.[89]

Fungi

[edit]The fungal component of a lichen is called themycobiont.The mycobiont may be anAscomyceteorBasidiomycete.[15]The associated lichens are called eitherascolichensorbasidiolichens,respectively. Living as asymbiontin a lichen appears to be a successful way for a fungus to derive essential nutrients, since about 20% of all fungal species have acquired this mode of life.[90]

Thalli produced by a given fungal symbiont with its differing partners may be similar,[citation needed]and the secondary metabolites identical,[citation needed]indicating[citation needed]that the fungus has the dominant role in determining the morphology of the lichen. But the same mycobiont with different photobionts may also produce very different growth forms.[83]Lichens are known in which there is one fungus associated with two or even three algal species.

Although each lichen thallus generally appears homogeneous, some evidence seems to suggest that the fungal component may consist of more than one genetic individual of that species.[citation needed]

Two or more fungal species can interact to form the same lichen.[91]

The following table lists theordersandfamiliesof fungi that include lichen-forming species.

Photobionts

[edit]

Thephotosyntheticpartner in a lichen is called aphotobiont.The photobionts in lichens come from a variety of simpleprokaryoticandeukaryoticorganisms. In the majority of lichens the photobiont is a green alga (Chlorophyta) or acyanobacterium.In some lichens both types are present; in such cases, the alga is typically the primary partner, with the cyanobacteria being located in cryptic pockets.[92]Algal photobionts are calledphycobionts,while cyanobacterial photobionts are calledcyanobionts.[41]About 90% of all known lichens have phycobionts, and about 10% have cyanobionts.[41]Approximately 100 species of photosynthetic partners from 40[41]genera and five distinct classes (prokaryotic:Cyanophyceae;eukaryotic:Trebouxiophyceae,Phaeophyceae,Chlorophyceae) have been found to associate with the lichen-forming fungi.[93]

Commonalgalphotobionts are from the generaTrebouxia,Trentepohlia,Pseudotrebouxia,orMyrmecia.Trebouxiais the most common genus of green algae in lichens, occurring in about 40% of all lichens. "Trebouxioid" means either a photobiont that is in the genusTrebouxia,or resembles a member of that genus, and is therefore presumably a member of the classTrebouxiophyceae.[33]The second most commonly represented green alga genus isTrentepohlia.[34]Overall, about 100 species of eukaryotes are known to occur as photobionts in lichens. All the algae are probably able to exist independently in nature as well as in the lichen.[91]

A "cyanolichen"is a lichen with acyanobacteriumas its main photosynthetic component (photobiont).[94]Most cyanolichen are also ascolichens, but a few basidiolichen likeDictyonemaandAcantholichenhave cyanobacteria as their partner.[95]

The most commonly occurring cyanobacteriumgenusisNostoc.[91]Other[34]commoncyanobacteriumphotobionts are fromScytonema.[15]Many cyanolichens are small and black, and havelimestoneas the substrate.[citation needed]Another cyanolichen group, thejelly lichensof the generaCollemaorLeptogiumare gelatinous and live on moist soils. Another group of large andfoliosespecies includingPeltigera,Lobaria,andDegeliaare grey-blue, especially when dampened or wet. Many of these characterize theLobarioncommunities of higher rainfall areas in western Britain, e.g., in theCeltic rain forest.Strains of cyanobacteria found in various cyanolichens are often closely related to one another.[96]They differ from the most closely related free-living strains.[96]

The lichen association is a close symbiosis. It extends the ecological range of both partners but is not always obligatory for their growth and reproduction in natural environments, since many of the algal symbionts can live independently. A prominent example is the algaTrentepohlia,which forms orange-coloured populations on tree trunks and suitable rock faces. Lichen propagules (diaspores) typically contain cells from both partners, although the fungal components of so-called "fringe species" rely instead on algal cells dispersed by the "core species".[74]

The same cyanobiont species can occur in association with different fungal species as lichen partners.[97]The same phycobiont species can occur in association with different fungal species as lichen partners.[41]More than one phycobiont may be present in a single thallus.[41]

A single lichen may contain several algalgenotypes.[98][99]These multiple genotypes may better enable response to adaptation to environmental changes, and enable the lichen to inhabit a wider range of environments.[100]

Controversy over classification method and species names

[edit]There are about 20,000 known lichenspecies.[15]But what is meant by "species" is different from what is meant by biological species in plants, animals, or fungi, where being the same species implies that there is a commonancestral lineage.[15]Because lichens are combinations of members of two or even three different biologicalkingdoms,these componentsmusthave adifferentancestral lineage from each other. By convention, lichens are still called "species" anyway, and are classified according to the species of their fungus, not the species of the algae or cyanobacteria. Lichens are given the same scientific name (binomial name) as the fungus in them, which may cause some confusion. The alga bears its own scientific name, which has no relationship to the name of the lichen or fungus.[79]

Depending on context, "lichenized fungus" may refer to the entire lichen, or to the fungus when it is in the lichen, which can be grown in culture in isolation from the algae or cyanobacteria. Some algae and cyanobacteria are found naturally living outside of the lichen. The fungal, algal, or cyanobacterial component of a lichen can be grown by itself in culture. When growing by themselves, the fungus, algae, or cyanobacteria have very different properties than those of the lichen. Lichen properties such as growth form, physiology, and biochemistry, are very different from the combination of the properties of the fungus and the algae or cyanobacteria.

The same fungus growing in combination with different algae or cyanobacteria, can produce lichens that are very different in most properties, meeting non-DNA criteria for being different "species". Historically, these different combinations were classified as different species. When the fungus is identified as being the same using modern DNA methods, these apparently different species get reclassified as thesamespecies under the current (2014) convention for classification by fungal component. This has led to debate about this classification convention. These apparently different "species" have their own independent evolutionary history.[2][83]

There is also debate as to the appropriateness of giving the same binomial name to the fungus, and to the lichen that combines that fungus with an alga or cyanobacterium (synecdoche). This is especially the case when combining the same fungus with different algae or cyanobacteria produces dramatically different lichen organisms, which would be considered different species by any measure other than the DNA of the fungal component. If the whole lichen produced by the same fungus growing in association with different algae or cyanobacteria, were to be classified as different "species", the number of "lichen species" would be greater.

Diversity

[edit]The largest number of lichenized fungi occur in theAscomycota,with about 40% of species forming such an association.[79]Some of these lichenized fungi occur in orders with nonlichenized fungi that live assaprotrophsorplant parasites(for example, theLeotiales,Dothideales,andPezizales). Other lichen fungi occur in only fiveordersin which all members are engaged in this habit (OrdersGraphidales,Gyalectales,Peltigerales,Pertusariales,andTeloschistales). Overall, about 98% of lichens have an ascomycetous mycobiont.[101]Next to the Ascomycota, the largest number of lichenized fungi occur in the unassignedfungi imperfecti,a catch-all category for fungi whose sexual form of reproduction has never been observed.[citation needed]Comparatively fewbasidiomycetesare lichenized, but these includeagarics,such as species ofLichenomphalia,clavarioid fungi,such as species ofMulticlavula,andcorticioid fungi,such as species ofDictyonema.

Identification methods

[edit]Lichen identification uses growth form, microscopy and reactions to chemical tests.

The outcome of the "Pd test" is called "Pd", which is also used as an abbreviation for the chemical used in the test,para-phenylenediamine.[33]If putting a drop on a lichen turns an area bright yellow to orange, this helps identify it as belonging to either the genusCladoniaorLecanora.[33]

Evolution and paleontology

[edit]The fossil record for lichens is poor.[102]The extreme habitats that lichens dominate, such as tundra, mountains, and deserts, are not ordinarily conducive to producing fossils.[102][103]There are fossilized lichens embedded in amber. The fossilizedAnziais found in pieces of amber in northern Europe and dates back approximately 40 million years.[104]Lichen fragments are also found in fossil leaf beds, such asLobariafrom Trinity County in northern California, US, dating back to the early to middleMiocene.[105]

The oldest fossil lichen in which both symbiotic partners have been recovered isWinfrenatia,an early zygomycetous (Glomeromycotan) lichen symbiosis that may have involved controlled parasitism,[citation needed]is permineralized in theRhynie Chertof Scotland, dating from earlyEarly Devonian,about 400 million years ago.[106]The slightly older fossilSpongiophytonhas also been interpreted as a lichen on morphological[107]and isotopic[108]grounds, although the isotopic basis is decidedly shaky.[109]It has been demonstrated thatSilurian-DevonianfossilsNematothallus[110]andPrototaxites[111]were lichenized. Thus lichenizedAscomycotaandBasidiomycotawere a component ofEarly Silurian-Devonianterrestrial ecosystems.[112][113]Newer research suggests that lichen evolved after the evolution of land plants.[114]

The ancestral ecological state of bothAscomycotaandBasidiomycotawas probablysaprobism,and independent lichenization events may have occurred multiple times.[115][116]In 1995, Gargas and colleagues proposed that there were at least five independent origins of lichenization; three in the basidiomycetes and at least two in the Ascomycetes.[117]Lutzoni et al. (2001) suggest lichenization probably evolved earlier and was followed by multiple independent losses. Some non-lichen-forming fungi may have secondarily lost the ability to form a lichen association. As a result, lichenization has been viewed as a highly successful nutritional strategy.[118][119]

LichenizedGlomeromycotamay extend well back into the Precambrian. Lichen-like fossils consisting of coccoid cells (cyanobacteria?) and thin filaments (mucoromycotinanGlomeromycota?) are permineralized in marinephosphoriteof theDoushantuo Formationin southern China. These fossils are thought to be 551 to 635 million years old orEdiacaran.[120]Ediacaranacritarchsalso have many similarities withGlomeromycotanvesicles and spores.[121]It has also been claimed thatEdiacaran fossilsincludingDickinsonia,[122]were lichens,[123]although this claim is controversial.[124]EndosymbioticGlomeromycotacomparable with livingGeosiphonmay extend back into theProterozoicin the form of 1500 million year oldHorodyskia[125]and 2200 million year oldDiskagma.[126]Discovery of these fossils suggest that fungi developed symbiotic partnerships with photoautotrophs long before the evolution of vascular plants, though the Ediacaran lichen hypothesis is largely rejected due to an inappropriate definition of lichens based on taphonomy and substrate ecology.[127]However, a 2019 study by the same scientist who rejected the Ediacaran lichen hypothesis, Nelsen, used new time-calibrated phylogenies to conclude that there is no evidence of lichen before the existence of vascular plants.[128]

Lecanoromycetes, one of the most common classes of lichen-forming fungi, diverged from its ancestor, which may have also been lichen forming, around 258 million years ago, during the late Paleozoic period. However, the closely related clade Euritiomycetes appears to have become lichen-forming only 52 million years ago, during the early Cenozoic period.[129]

Ecology and interactions with environment

[edit]Substrates and habitats

[edit]

Lichens grow on and in a wide range of substrates and habitats, including some of the most extreme conditions on earth.[130]They are abundant growing on bark, leaves, and hanging fromepiphytebranches inrain forestsand intemperate woodland.They grow on bare rock, walls, gravestones, roofs, and exposed soil surfaces. They can survive in some of the most extreme environments on Earth:arctic tundra,hot drydeserts,rocky coasts, and toxicslag heaps.They can live inside solid rock, growing between the grains, and in the soil as part of abiological soil crustin arid habitats such as deserts. Some lichens do not grow on anything, living out their lives blowing about the environment.[2]

When growing on mineral surfaces, some lichens slowly decompose their substrate by chemically degrading and physically disrupting the minerals, contributing to the process ofweatheringby which rocks are gradually turned into soil. While this contribution to weathering is usually benign, it can cause problems for artificial stone structures. For example, there is an ongoing lichen growth problem onMount Rushmore National Memorialthat requires the employment of mountain-climbing conservators to clean the monument.[131]

Lichens are notparasiteson the plants they grow on, but only use them as a substrate. The fungi of some lichen species may "take over" the algae of other lichen species.[13][132]Lichens make their own food from their photosynthetic parts and by absorbing minerals from the environment.[13]Lichens growing on leaves may have the appearance of being parasites on the leaves, but they are not. Some lichens inDiploschistesparasitise other lichens.Diploschistes muscorumstarts its development in the tissue of a hostCladoniaspecies.[52]: 30 [34]: 171

In the arctic tundra, lichens, together withmossesandliverworts,make up the majority of theground cover,which helps insulate the ground and may provide forage for grazing animals. An example is "reindeer moss",which is a lichen, not a moss.[13]

There are only two species of known permanently submerged lichens;Hydrothyria venosais found in fresh water environments, andVerrucaria serpuloidesis found in marine environments.[133]

A crustose lichen that grows on rock is called asaxicolous lichen.[33][36]: 159 Crustose lichens that grow on the rock areepilithic,and those that grow immersed inside rock, growing between the crystals with only their fruiting bodies exposed to the air, are calledendolithic lichens.[32][36]: 159 [94]A crustose lichen that grows on bark is called acorticolous lichen.[36]: 159 A lichen that grows on wood from which the bark has been stripped is called alignicolous lichen.[42]Lichens that grow immersed inside plant tissues are calledendophloidic lichensorendophloidal lichens.[32][36]: 159 Lichens that use leaves as substrates, whether the leaf is still on the tree or on the ground, are calledepiphyllousorfoliicolous.[41]Aterricolous lichengrows on the soil as a substrate. Many squamulose lichens are terricolous.[36]: 159 Umbilicate lichensare foliose lichens that are attached to the substrate at only one point.[32]Avagrant lichenis not attached to a substrate at all, and lives its life being blown around by the wind.

Lichens and soils

[edit]In addition to distinct physical mechanisms by which lichens break down raw stone, studies indicate lichens attack stone chemically, entering newly chelated minerals into the ecology. The substances exuded by lichens, known for their strong ability to bind and sequester metals, along with the common formation of new minerals, especially metaloxalates,and the traits of the substrates they alter, all highlight the important role lichens play in the process of chemicalweathering.[134]Over time, this activity creates new fertile soil from stone.

Lichens may beimportant in contributing nitrogento soils in some deserts through being eaten, along with their rock substrate, by snails, which then defecate, putting the nitrogen into the soils.[135]Lichens help bind and stabilize soil sand in dunes.[2]In deserts and semi-arid areas, lichens are part of extensive, livingbiological soil crusts,essential for maintaining the soil structure.[2]

Ecological interactions

[edit]Lichens arepioneer species,among the first living things to grow on bare rock or areas denuded of life by a disaster.[2]Lichens may have to compete with plants for access to sunlight, but because of their small size and slow growth, they thrive in places where higher plants have difficulty growing. Lichens are often thefirst to settlein places lacking soil, constituting the sole vegetation in some extreme environments such as those found at high mountain elevations and at high latitudes.[136]Some survive in the tough conditions of deserts, and others on frozen soil of the Arctic regions.[137]

A major ecophysiological advantage of lichens is that they arepoikilohydric(poikilo- variable,hydric- relating to water), meaning that though they have little control over the status of their hydration, they can tolerate irregular and extended periods of severedesiccation.Like somemosses,liverworts,fernsand a fewresurrection plants,upon desiccation, lichens enter a metabolic suspension or stasis (known ascryptobiosis) in which the cells of the lichen symbionts are dehydrated to a degree that halts most biochemical activity. In this cryptobiotic state, lichens can survive wider extremes of temperature, radiation and drought in the harsh environments they often inhabit.

Lichens do not have roots and do not need to tap continuous reservoirs of water like most higher plants, thus they can grow in locations impossible for most plants, such as bare rock, sterile soil or sand, and various artificial structures such as walls, roofs, and monuments. Many lichens also grow asepiphytes(epi- on the surface,phyte- plant) on plants, particularly on the trunks and branches of trees. When growing on plants, lichens are notparasites;they do not consume any part of the plant nor poison it. Lichens produceallelopathicchemicals that inhibit the growth of mosses. Some ground-dwelling lichens, such as members of the subgenusCladina(reindeer lichens), produce allelopathic chemicals that leach into the soil and inhibit the germination of seeds, spruce and other plants.[138]Stability (that is, longevity) of theirsubstrateis a major factor of lichen habitats. Most lichens grow on stable rock surfaces or the bark of old trees, but many others grow on soil and sand. In these latter cases, lichens are often an important part of soil stabilization; indeed, in some desert ecosystems,vascular (higher) plantseeds cannot become established except in places where lichen crusts stabilize the sand and help retain water.

Lichens may be eaten by some animals, such asreindeer,living inarcticregions. Thelarvaeof a number ofLepidopteraspecies feed exclusively on lichens. These includecommon footmanandmarbled beauty.They are very low in protein and high in carbohydrates, making them unsuitable for some animals. TheNorthern flying squirreluses it for nesting, food and winter water.

Effects of air pollution

[edit]

If lichens are exposed to air pollutants at all times, without anydeciduousparts, they are unable to avoid the accumulation of pollutants. Also lackingstomataand acuticle,lichens may absorbaerosolsand gases over the entire thallus surface from which they may readilydiffuseto the photobiont layer.[139]Because lichens do not possess roots, their primary source of mostelementsis the air, and therefore elemental levels in lichens often reflect the accumulated composition of ambient air. The processes by which atmospheric deposition occurs includefoganddew,gaseous absorption, and dry deposition.[140]Consequently, environmental studies with lichens emphasize their feasibility as effectivebiomonitorsof atmospheric quality.[139]

Not all lichens are equally sensitive toair pollutants,so different lichen species show different levels of sensitivity to specific atmospheric pollutants.[141]The sensitivity of a lichen to air pollution is directly related to the energy needs of the mycobiont, so that the stronger the dependency of the mycobiont on the photobiont, the more sensitive the lichen is to air pollution.[142]Upon exposure to air pollution, the photobiont may use metabolic energy for repair of its cellular structures that would otherwise be used for maintenance of its photosynthetic activity, therefore leaving less metabolic energy available for the mycobiont. The alteration of the balance between the photobiont and mycobiont can lead to the breakdown of the symbiotic association. Therefore, lichen decline may result not only from the accumulation of toxic substances, but also from altered nutrient supplies that favor one symbiont over the other.[139]

This interaction between lichens and air pollution has been used as a means of monitoring air quality since 1859, with more systematic methods developed byWilliam Nylanderin 1866.[2]

Human use

[edit]

Food

[edit]Lichens are eaten by many different cultures across the world. Although some lichens are only eaten in times offamine,others are astaple foodor even adelicacy.Two obstacles are often encountered when eating lichens: lichenpolysaccharidesare generally indigestible to humans, and lichens usually contain mildly toxicsecondary compoundsthat should be removed before eating. Very few lichens are poisonous, but those high invulpinic acidorusnic acidare toxic.[143]Most poisonous lichens are yellow.[citation needed]

In the past,Iceland moss(Cetraria islandica) was an important source of food for humans in northern Europe, and was cooked as a bread, porridge, pudding, soup, or salad.Bryoria fremontii(edible horsehair lichen) was an important food in parts of North America, where it was usuallypitcooked.Northern peoples in North America and Siberia traditionally eat the partially digestedreindeer lichen(Cladinaspp.) after they remove it from therumenof caribou or reindeer that have been killed.Rock tripe(Umbilicariaspp. andLasaliaspp.) is a lichen that has frequently been used as an emergency food in North America, and one species,Umbilicaria esculenta,(iwatakein Japanese) is used in a variety of traditional Korean and Japanese foods.

Lichenometry

[edit]

Lichenometry is a technique used to determine the age of exposed rock surfaces based on the size of lichen thalli. Introduced by Beschel in the 1950s,[144]the technique has found many applications. it is used inarchaeology,palaeontology,andgeomorphology.It uses the presumed regular but slow rate of lichen growth to determine theage of exposed rock.[38]: 9 [145]Measuring the diameter (or other size measurement) of the largest lichen of a species on a rock surface indicates the length of time since the rock surface was first exposed. Lichen can be preserved on old rock faces for up to[citation needed]10,000 years, providing the maximum age limit of the technique, though it is most accurate (within 10% error) when applied to surfaces that have been exposed for less than 1,000 years.[146]Lichenometry is especially useful for dating surfaces less than 500 years old, asradiocarbon datingtechniques are less accurate over this period.[147]The lichens most commonly used for lichenometry are those of the generaRhizocarpon(e.g. the speciesRhizocarpon geographicum,map lichen) andXanthoria.

Biodegradation

[edit]Lichens have been shown to degradepolyester resins,as can be seen in archaeological sites in the Roman city ofBaelo Claudiain Spain.[148]Lichens can accumulate several environmental pollutants such as lead, copper, andradionuclides.[149]Some species of lichen, such asParmelia sulcata(called a hammered shield lichen, among other names) andLobaria pulmonaria(lung lichen), and many in theCladoniagenus,have been shown to produceserine proteasescapable of the degradation of pathogenic forms ofprion protein(PrP), which may be useful in treating contaminated environmental reservoirs.[150][151][152]

Dyes

[edit]Many lichens produce secondary compounds, includingpigmentsthat reduce harmful amounts of sunlight and powerful toxins that deterherbivoresor kill bacteria. These compounds are very useful for lichen identification, and have had economic importance asdyessuch ascudbearor primitiveantibiotics.

ApH indicator(which can indicate acidic or basic substances) calledlitmusis a dye extracted from the lichenRoccella tinctoria( "dyer's weed" )[153]by boiling. It gives its name to the well-knownlitmus test.

Traditional dyes of the Scottish HighlandsforHarris tweed[2]and other traditional cloths were made from lichens, including the orangeXanthoria parietina( "common orange lichen" ) and the grey foliaceousParmelia saxatiliscommon on rocks and known colloquially as "crottle".

There are reports dating almost 2,000 years old of lichens being used to make purple and red dyes.[154]Of great historical and commercial significance are lichens belonging to the familyRoccellaceae,commonly called orchella weed or orchil.Orceinand other lichen dyes have largely been replaced bysynthetic versions.

Traditional medicine and research

[edit]Historically, intraditional medicineof Europe,Lobaria pulmonariawas collected in large quantities as "lungwort", due to its lung-like appearance (the "doctrine of signatures"suggesting that herbs can treat body parts that they physically resemble).Similarly,Peltigera leucophlebia( "ruffled freckled pelt" ) was used as a supposed cure forthrush,due to the resemblance of its cephalodia to the appearance of the disease.[34]

Lichens producemetabolitesbeing researched for their potential therapeutic or diagnostic value.[155]Some metabolites produced by lichens are structurally and functionally similar tobroad-spectrum antibioticswhile few are associated respectively to antiseptic similarities.[156]Usnic acidis the most commonly studied metabolite produced by lichens.[156]It is also under research as abactericidalagent againstEscherichia coliandStaphylococcus aureus.[157]

Aesthetic appeal

[edit]

Colonies of lichens may be spectacular in appearance, dominating the surface of the visual landscape as part of the aesthetic appeal to visitors ofYosemite National Park,Sequoia National Park,and theBay of Fires.[38]: 2 Orangeandyellowlichens add to the ambience of desert trees, tundras, and rocky seashores. Intricate webs of lichenshanging from tree branchesadd a mysterious aspect to forests. Fruticose lichens are used inmodel railroading[158]and other modeling hobbies as a material for making miniature trees and shrubs.

In literature

[edit]In earlyMidrashicliterature, the Hebrew word "vayilafeth"inRuth3:8 is explained as referring toRuthentwining herself aroundBoazlike lichen.[159]The 10th century Arab physicianAl-Tamimimentions lichens dissolved invinegarandrose waterbeing used in his day for the treatment of skin diseases and rashes.[160]

The plot ofJohn Wyndham's science fiction novelTrouble with Lichenrevolves around an anti-aging chemical extracted from a lichen.

History

[edit]

Although lichens had been recognized as organisms for quite some time, it was not until 1867, when Swiss botanistSimon Schwendenerproposed his dual theory of lichens, that lichens are a combination of fungi with algae or cyanobacteria, whereby the true nature of the lichen association began to emerge.[161]Schwendener's hypothesis, which at the time lacked experimental evidence, arose from his extensive analysis of the anatomy and development in lichens, algae, and fungi using alight microscope.Many of the leading lichenologists at the time, such asJames CrombieandNylander,rejected Schwendener's hypothesis because the consensus was that all living organisms were autonomous.[161]

Other prominent biologists, such asHeinrich Anton de Bary,Albert Bernhard Frank,Beatrix Potter,Melchior TreubandHermann Hellriegel,were not so quick to reject Schwendener's ideas and the concept soon spread into other areas of study, such as microbial, plant, animal and human pathogens.[161][162][163]When the complex relationships between pathogenic microorganisms and their hosts were finally identified, Schwendener's hypothesis began to gain popularity. Further experimental proof of the dual nature of lichens was obtained whenEugen Thomaspublished his results in 1939 on the first successful re-synthesis experiment.[161]

In the 2010s, a new facet of the fungi–algae partnership was discovered.Toby Spribilleand colleagues found that many types of lichen that were long thought to beascomycete–algae pairs were actually ascomycete–basidiomycete–algae trios. The third symbiotic partner in many lichens is a basidiomycete yeast.[1][164]

See also

[edit]- Lichenology

- Lichens and nitrogen cycling

- Mycophycobiosis- a symbiosis where a fungus lives in the macroscopic thallus of fresh water and marine algae; technically not a lichen but a similar phenomenon where fungi and algae are in symbiosis

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcdSpribille, Toby; Tuovinen, Veera; Resl, Philipp; Vanderpool, Dan; Wolinski, Heimo; Aime, M. Catherine; Schneider, Kevin; Stabentheiner, Edith; Toome-Heller, Merje (21 July 2016)."Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens".Science.353(6298): 488–92.Bibcode:2016Sci...353..488S.doi:10.1126/science.aaf8287.ISSN0036-8075.PMC5793994.PMID27445309.

- ^abcdefghijklmnoLepp, Heino (7 March 2011)."What is a lichen?".Australian National Botanic Gardens. Archived fromthe originalon 2 July 2014.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^"Introduction to Lichens – An Alliance between Kingdoms".University of California Museum of Paleontology.Archived22 August 2014 at theWayback Machine.

- ^abcdeBrodo, Irwin M. and Duran Sharnoff, Sylvia (2001)Lichens of North America.ISBN978-0300082494.

- ^"Yeast emerges as hidden third partner in lichen symbiosis".ScienceDaily.21 July 2016.Retrieved31 March2024.

- ^Kumpula, Jouko; Lefrère, Stéphanie C.; Nieminen, Mauri (1 January 2004)."The Use of Woodland Lichen Pasture by Reindeer in Winter with Easy Snow Conditions".Arctic.57(3).doi:10.14430/arctic504.ISSN1923-1245.

- ^Fröberg, Lars; Baur, Anette; Baur, Bruno (January 1993)."Differential herbivore damage to calcicolous lichens by snails".The Lichenologist.25(1): 83.doi:10.1017/s002428299300009x.ISSN0024-2829.

- ^Leinaas, Hans Petter; Fjellberg, Arne (June 1985)."Habitat Structure and Life History Strategies of Two Partly Sympatric and Closely Related, Lichen Feeding Collembolan Species".Oikos.44(3): 448.Bibcode:1985Oikos..44..448L.doi:10.2307/3565786.ISSN0030-1299.JSTOR3565786.

- ^Gerson, U. (October 1973)."Lichen-Arthropod Associations".The Lichenologist.5(5–6): 434–443.doi:10.1017/S0024282973000484.ISSN0024-2829.S2CID85020765.

- ^abGalloway, D.J. (13 May 1999)."Lichen Glossary".Australian National Botanic Gardens. Archived fromthe originalon 6 December 2014.

- ^Margulis, Lynn;Barreno, EVA (2003)."Looking at Lichens".BioScience.53(8): 776.doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0776:LAL]2.0.CO;2.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqSharnoff, Stephen (2014)Field Guide to California Lichens,Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-19500-2

- ^abcdefghijkSpeer, Brian R; Ben Waggoner (May 1997)."Lichens: Life History & Ecology".University of California Museum of Paleontology.Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2015.Retrieved28 April2015.

- ^Sisson, Liv; Vigus, Paula (2023).Fungi of Aotearoa: a curious forager's field guide.Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books. p. 66.ISBN978-1-76104-787-9.OCLC1372569849.

- ^abcde"Lichens: Systematics, University of California Museum of Paleontology".Archivedfrom the original on 24 February 2015.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^Lendemer, J. C. (2011). "A taxonomic revision of the North American species ofLeprarias.l. that produce divaricatic acid, with notes on the type species of the genusL. incana".Mycologia.103(6): 1216–1229.doi:10.3852/11-032.PMID21642343.S2CID34346229.

- ^abcdCasano, L. M.; Del Campo, E. M.; García-Breijo, F. J.; Reig-Armiñana, J; Gasulla, F; Del Hoyo, A; Guéra, A; Barreno, E (2011). "TwoTrebouxiaalgae with different physiological performances are ever-present in lichen thalli ofRamalina farinacea.Coexistence versus competition? ".Environmental Microbiology(Submitted manuscript).13(3): 806–818.Bibcode:2011EnvMi..13..806C.doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02386.x.hdl:10251/60269.PMID21134099.

- ^abHonegger, R.(1991)Fungal evolution: symbiosis and morphogenesis, Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation,Margulis, L., and Fester, R. (eds). Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press, pp. 319–340.

- ^abGrube, M; Cardinale, M; De Castro, J. V. Jr.; Müller, H; Berg, G (2009)."Species-specific structural and functional diversity of bacterial communities in lichen symbioses".The ISME Journal.3(9): 1105–1115.Bibcode:2009ISMEJ...3.1105G.doi:10.1038/ismej.2009.63.PMID19554038.

- ^abBarreno, E., Herrera-Campos, M., García-Breijo, F., Gasulla, F., and Reig-Armiñana, J. (2008)"Non photosynthetic bacteria associated to cortical structures on Ramalina andUsneathalli from Mexico ".Asilomar, Pacific Grove, CA, USA: Abstracts IAL 6- ABLS Joint Meeting.

- ^abMorris J, Purvis W (2007).Lichens (Life).London: The Natural History Museum. p. 19.ISBN978-0-565-09153-8.

- ^"Lichen - The Little Things That Matter (U.S. National Park Service)".nps.gov.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^Harper, Douglas."lichen".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^lichen.Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short.A Latin DictionaryonPerseus Project.

- ^λειχήν.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;A Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project.

- ^λείχεινinLiddellandScott.

- ^Beekes, Robert S. P.(2010). "s.v. λειχήν, λείχω".Etymological Dictionary of Greek.Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series. Vol. 1. With the assistance of Lucien van Beek. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 846–47.ISBN9789004174184.

- ^"Lichen".Cambridge Dictionary.Retrieved8 September2022.

- ^Wordsworth, Dot (17 November 2012)."Lichen".spectator.co.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2014.Retrieved8 September2022.

- ^The Oxford English Dictionary cites only the "liken" pronunciation:"lichen".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.Retrieved10 January2018.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^abcdef"Lichens and Bryophytes, Michigan State University, 10-25-99".Archived fromthe originalon 5 October 2011.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^abcdefghijLichen Vocabulary, Lichens of North America Information, Sylvia and Stephen Sharnoff,[1]Archived20 January 2015 at theWayback Machine

- ^abcdefghijk"Alan Silverside's Lichen Glossary (p-z), Alan Silverside".Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2014.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^abcdefghDobson, F.S. (2011).Lichens, an illustrated guide to the British and Irish species.Slough, UK: Richmond Publishing Co.ISBN9780855463151.

- ^abcdefg"Foliose lichens, Lichen Thallus Types, Allan Silverside".Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2014.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^abcdefghijklmMosses Lichens & Ferns of Northwest North America,Dale H. Vitt, Janet E. Marsh, Robin B. Bovey, Lone Pine Publishing Company,ISBN0-295-96666-1

- ^abcd"Lichens, Saguaro-Juniper Corporation".Archived fromthe originalon 10 May 2015.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^abcMcCune, B.; Grenon, J.; Martin, E.; Mutch, L.S.; Martin, E.P. (March 2007). "Lichens in relation to management issues in the Sierra Nevada national parks".North American Fungi.2:1–39.doi:10.2509/pnwf.2007.002.003(inactive 16 April 2024).

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - ^abcdMichigan Lichens, Julie Jones Medlin, B. Jain Publishers, 1996,ISBN0877370397,9780877370390,[2]Archived24 November 2016 at theWayback Machine

- ^abcdefghijLichens: More on Morphology, University of California Museum of Paleontology,[3]Archived28 February 2015 at theWayback Machine

- ^abcdefghijkl"Lichen Photobionts, University of Nebraska Omaha"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 October 2014.

- ^ab"Alan Silverside's Lichen Glossary (g-o), Alan Silverside".Archivedfrom the original on 2 November 2014.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^abcBüdel, B.; Scheidegger, C. (1996). "Thallus morphology and anatomy".Lichen Biology.pp. 37–64.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511790478.005.ISBN9780511790478.

- ^abHeiđmarsson, Starri; Heidmarsson, Starri (1996). "Pruina as a Taxonomic Character in the Lichen GenusDermatocarpon".The Bryologist.99(3): 315–320.doi:10.2307/3244302.JSTOR3244302.

- ^Sharnoff, Sylvia and Sharnoff, Stephen."Lichen Biology and the Environment"Archived17 October 2015 at theWayback Machine.sharnoffphotos

- ^Pogoda, C. S.; Keepers, K. G.; Lendemer, J. C.; Kane, N. C.; Tripp, E. A. (2018). "Reductions in complexity of mitochondrial genomes in lichen-forming fungi shed light on genome architecture of obligate symbioses – Wiley Online Library".Molecular Ecology.27(5): 1155–1169.doi:10.1111/mec.14519.PMID29417658.S2CID4238109.

- ^Spribille, Toby; Tuovinen, Veera; Resl, Philipp; Vanderpool, Dan; Wolinski, Heimo; Aime, M. Catherine; Schneider, Kevin; Stabentheiner, Edith; Toome-Heller, Merje; Thor, Göran; Mayrhofer, Helmut; Johannesson, Hanna; McCutcheon, John P. (29 July 2016)."Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens".Science.353(6298): 488–492.Bibcode:2016Sci...353..488S.doi:10.1126/science.aaf8287.PMC5793994.PMID27445309.

- ^Skaloud, P; Peksa, O (2010). "Evolutionary inferences based on ITS rDNA and actin sequences reveal extensive diversity of the common lichen algaAsterochloris(Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) ".Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.54(1): 36–46.doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.09.035.PMID19853051.

- ^Spribille, Toby; Tuovinen, Veera; Resl, Philipp; Vanderpool, Dan; Wolinski, Heimo; Aime, M. Catherine; Schneider, Kevin; Stabentheiner, Edith; Toome-Heller, Merje; Thor, Göran; Mayrhofer, Helmut (29 July 2016)."Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens".Science.353(6298): 488–492.Bibcode:2016Sci...353..488S.doi:10.1126/science.aaf8287.ISSN0036-8075.PMC5793994.PMID27445309.

- ^abcdRamel, Gordon."What is a Lichen?".Earthlife Web.Archivedfrom the original on 19 January 2015.Retrieved20 January2015.

- ^abAhmad gian V. (1993).The Lichen Symbiosis.New York: John Wiley & Sons.ISBN978-0-471-57885-7.

- ^abHonegger, R. (1988). "Mycobionts". In Nash III, T.H. (ed.).Lichen Biology.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (published 1996).ISBN978-0-521-45368-4.

- ^Ferry, B. W., Baddeley, M. S. & Hawksworth, D. L. (editors) (1973)Air Pollution and Lichens.Athlone Press, London.

- ^Rose C. I., Hawksworth D. L. (1981). "Lichen recolonization in London's cleaner air".Nature.289(5795): 289–292.Bibcode:1981Natur.289..289R.doi:10.1038/289289a0.S2CID4320709.

- ^Hawksworth, D.L. and Rose, F. (1976)Lichens as pollution monitors.Edward Arnold, Institute of Biology Series, No. 66.ISBN0713125551

- ^"Oak Moss Absolute Oil, Evernia prunastri, Perfume Fixative".Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2014.Retrieved19 September2014.

- ^Skogland, Terje (1984). "Wild reindeer foraging-niche organization".Ecography.7(4): 345.Bibcode:1984Ecogr...7..345S.doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1984.tb01138.x.

- ^Lawrey, James D.; Diederich, Paul (2003)."Lichenicolous Fungi: Interactions, Evolution, and Biodiversity"(PDF).The Bryologist.106:80.doi:10.1639/0007-2745(2003)106[0080:LFIEAB]2.0.CO;2.S2CID85790408.Archived(PDF)from the original on 3 January 2011.Retrieved2 May2011.

- ^Hagiwara K, Wright PR, et al. (March 2015). "Comparative analysis of the antioxidant properties of Icelandic and Hawaiian lichens".Environmental Microbiology.18(8): 2319–2325.doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12850.PMID25808912.S2CID13768322.

- ^Odabasoglu F, Aslan A, Cakir A, et al. (March 2005). "Antioxidant activity, reducing power and total phenolic content of some lichen species".Fitoterapia.76(2): 216–219.doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2004.05.012.PMID15752633.

- ^abHauck, Markus; Jürgens, Sascha-René; Leuschner, Christoph (2010). "Norstictic acid: Correlations between its physico-chemical characteristics and ecological preferences of lichens producing this depsidone".Environmental and Experimental Botany.68(3): 309.Bibcode:2010EnvEB..68..309H.doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.01.003.

- ^ab"The Earth Life Web, Growth and Development in Lichens".earthlife.net. Archived fromthe originalon 28 May 2015.Retrieved12 October2014.

- ^Rosenwinkel, Swenja; Korup, Oliver; Landgraf, Angela; Dzhumabaeva, Atyrgul (2015)."Limits to lichenometry".Quaternary Science Reviews.129:229–238.Bibcode:2015QSRv..129..229R.doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.10.031.

- ^Miller, G. H.; Andrews, J. T. (April 1972)."Quaternary History of Northern Cumberland Peninsula, East Baffin Island, N.W.T., Canada Part VI: Preliminary Lichen Growth Curve for Rhizocarpon geographicum".GSA Bulletin.83(4): 1133–1138.doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1972)83[1133:QHONCP]2.0.CO;2.

- ^Haworth, Leah A.; Calkin, Parker E.; Ellis, James M. (1986)."Direct Measurement of Lichen Growth in the Central Brooks Range, Alaska, U.S.A., and Its Application to Lichenometric Dating, Arctic and Alpine Research".Arctic and Alpine Research.18(3): 289–296.doi:10.2307/1550886.JSTOR1550886.

- ^Benedict, James B. (January 2009)."A Review of Lichenometric Dating and Its Applications to Archaeology".American Antiquity.74(1): 143–172.doi:10.1017/S0002731600047545.S2CID83108496.

- ^Nash III, Thomas H. (2008). "Introduction". In Nash III, T.H. (ed.).Lichen Biology(2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–8.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511790478.002.ISBN978-0-521-69216-8.

- ^Baldwin, Emily (26 April 2012)."Lichen survives harsh Mars environment".Skymania News. Archived fromthe originalon 28 May 2012.Retrieved27 April2012.

- ^Sheldrake, Merlin (2020).Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures.Bodley Head. p. 94.ISBN978-1847925206.

- ^"ESA – Human Spaceflight and Exploration – Lichen survives in space".Archivedfrom the original on 26 February 2010.Retrieved16 February2010.

- ^Sancho, L. G.; De La Torre, R.; Horneck, G.; Ascaso, C.; De Los Rios, A.; Pintado, A.; Wierzchos, J.; Schuster, M. (2007). "Lichens survive in space: results from the 2005 LICHENS experiment".Astrobiology.7(3): 443–454.Bibcode:2007AsBio...7..443S.doi:10.1089/ast.2006.0046.PMID17630840.S2CID4121180.

- ^Eichorn, Susan E., Evert, Ray F., and Raven, Peter H. (2005).Biology of Plants.New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 1.ISBN0716710072.

- ^Cook, Rebecca; McFarland, Kenneth (1995).General Botany 111 Laboratory Manual.Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee. p. 104.

- ^abA. N. Rai; B. Bergman; Ulla Rasmussen (31 July 2002).Cyanobacteria in Symbiosis.Springer. p. 59.ISBN978-1-4020-0777-4.Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2013.Retrieved2 June2013.

- ^Law, R.; Lewis, D. H. (November 1983)."Biotic environments and the maintenance of sex-some evidence from mutualistic symbioses".Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.20(3): 249–276.doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1983.tb01876.x.ISSN0024-4066.

- ^Škaloud, Pavel; Steinová, Jana; Řídká, Tereza; Vančurová, Lucie; Peksa, Ondřej (4 May 2015)."Assembling the challenging puzzle of algal biodiversity: species delimitation within the genusAsterochloris(Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta)".Journal of Phycology.51(3): 507–527.Bibcode:2015JPcgy..51..507S.doi:10.1111/jpy.12295.ISSN0022-3646.PMID26986666.S2CID25190572.

- ^Ramel, Gordon."Lichen Reproductive Structures".Archived fromthe originalon 28 February 2014.Retrieved22 August2014.

- ^abcMurtagh GJ, Dyer PS, Crittenden PD (April 2000). "Sex and the single lichen".Nature.404(6778): 564.Bibcode:2000Natur.404..564M.doi:10.1038/35007142.PMID10766229.S2CID4425228.

- ^abcKirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (2008).Dictionary of the Fungi(10th ed.). Wallingford: CABI. pp. 378–381.ISBN978-0-85199-826-8.

- ^Lücking, Robert; Hodkinson, Brendan P.; Leavitt, Steven D. (2017). "The 2016 classification of lichenized fungi in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota–Approaching one thousand genera".The Bryologist.119(4): 361–416.doi:10.1639/0007-2745-119.4.361.JSTOR44250015.S2CID90258634.

- ^Lücking, Robert; Hodkinson, Brendan P.; Leavitt, Steven D. (2017). "Corrections and amendments to the 2016 classification of lichenized fungi in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota".The Bryologist.120(1): 58–69.doi:10.1639/0007-2745-120.1.058.S2CID90363578.

- ^Lücking, Robert; Rivas-Plata, E.; Chavez, J.L.; Umaña, L.; Sipman, H.J.M. (2009). "How many tropical lichens are there… really?".Bibliotheca Lichenologica.100:399–418.

- ^abc"Form and structure –StictaandDendriscocaulon".Australian National Botanic Gardens. Archived fromthe originalon 28 April 2014.Retrieved18 September2014.

- ^Lutzoni, F.; Kauff, F.; Cox, C. J.; McLaughlin, D.; Celio, G.; Dentinger, B.; Padamsee, M.; Hibbett, D.; et al. (2004)."Assembling the fungal tree of life: progress, classification, and evolution of subcellular traits".American Journal of Botany.91(10): 1446–1480.doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1446.PMID21652303.S2CID9432006.

- ^Sanders, W. B.; Moe, R. L.; Ascaso, C. (2004). "The intertidal marine lichen formed by the pyrenomycete fungusVerrucaria tavaresiae(Ascomycotina) and the brown algaPetroderma maculiforme(Phaeophyceae): thallus organization and symbiont interaction – NCBI ".American Journal of Botany.91(4): 511–22.doi:10.3732/ajb.91.4.511.hdl:10261/31799.PMID21653406.

- ^"Mutualisms between fungi and algae – New Brunswick Museum".Archivedfrom the original on 18 September 2018.Retrieved4 October2018.

- ^Miller, Kathy Ann; Pérez-Ortega, Sergio (May 2018)."Challenging the lichen concept: Turgidosculum ulvae – Cambridge".The Lichenologist.50(3): 341–356.doi:10.1017/S0024282918000117.S2CID90117544.Archivedfrom the original on 7 October 2018.Retrieved7 October2018.

- ^Rybalka, N.; Wolf, M.; Andersen, R. A.; Friedl, T. (2013)."Congruence of chloroplast – BMC Evolutionary Biology – BioMed Central".BMC Evolutionary Biology.13:39.doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-39.PMC3598724.PMID23402662.

- ^Lutzoni, Francois; Pagel, Mark; Reeb, Valerie (21 June 2001)."Major fungal lineages are derived from lichen symbiotic ancestors".Nature.411(6840): 937–940.Bibcode:2001Natur.411..937L.doi:10.1038/35082053.PMID11418855.S2CID4414913.

- ^Hawksworth, D.L. (1988). "The variety of fungal-algal symbioses, their evolutionary significance, and the nature of lichens".Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society.96:3–20.doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1988.tb00623.x.S2CID49717944.

- ^abcRikkinen J. (1995). "What's behind the pretty colors? A study on the photobiology of lichens".Bryobrothera.4(3): 375–376.doi:10.2307/3244316.JSTOR3244316.

- ^Luecking, Robert (25 February 2015)."One Fungus - Two Lichens".Field Museum of Natural History.Retrieved25 February2022.

- ^Friedl, T.; Büdel, B. (1996). "Photobionts". In Nash III, T.H. (ed.).Lichen Biology.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–26.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511790478.003.ISBN978-0-521-45368-4.