List of uncrewed NASA missions

Since 1958,NASAhas overseen more than 1,000uncrewedmissions into Earth orbit or beyond.[1]It has both launched its own missions and provided funding for private-sector missions. A number of NASA missions, including theExplorers Program,Voyager program,andNew Frontiers program,are ongoing.

List of missions[edit]

Explorers Program (1958–present)[edit]

The Explorer program has launched more than 90 missions since it began more than five decades ago. It has matured into one of NASA's lower-cost mission programs.[2]

The program started as a U.S. Army proposal to place a scientific satellite into orbit during theInternational Geophysical Year(1957–58). However, that proposal was rejected in favor of the U.S. Navy'sProject Vanguard.The Explorer program was later reestablished to catch up with the Soviet Union after the launch ofSputnik 1in October 1957.Explorer 1was launched January 31, 1958; at this time the project still belonged to theArmy Ballistic Missile Agency(ABMA) and theJet Propulsion Laboratory(JPL).[3]Besides being the first U.S. satellite, it is known for discovering theVan Allen radiation belt.[4]

The Explorer program was later transferred to NASA, which continued to use the name for an ongoing series of relatively small space missions, typically an artificial satellite with a science focus. Over the years, NASA has launched a series of Explorer spacecraft carrying a wide variety of scientific investigations.

Pioneer program (1958–1978)[edit]

The Pioneer program was a series of NASA uncrewed space missions designed for planetary exploration. There were a number of missions in the program, most notablyPioneer 10andPioneer 11,which explored the outer planets and left theSolar System.Both carry agolden plaque,depicting a man and a woman and information about the origin and the creators of the probes, should anyextraterrestrialsfind them someday.[5]

Additionally, thePioneer mission to Venusconsisted of two components, launched separately. Pioneer Venus 1 (Pioneer Venus Orbiter) was launched in May 1978 and remained in orbit until 1992. Pioneer Venus 2 (Pioneer Venus Multiprobe), launched in August 1978, sent four small probes into the Venusian atmosphere.[6]

Project Echo (1960–1964)[edit]

Project Echo was the first passivecommunications satelliteexperiment. Each spacecraft was a metalizedballoon satelliteto be inflated in space and acting as a passivereflectorofmicrowavesignals. Communication signals were bounced off of them from one point on Earth to another.[7] NASA's Echo 1 satellite was built byGilmore SchjeldahlCompany inNorthfield, Minnesota.Following the failure of theDelta rocketcarrying Echo 1 on May 13, 1960, Echo 1A was put successfully into orbit by another Thor-Delta,[8][9]and the first microwave transmission was received on August 12, 1960.

Echo 2 was a 41.1-meter (135 ft) diametermetalized PET filmballoon, which was the last balloon satellite launched by Project Echo.[10]It used an improved inflation system to improve the balloon's smoothness andsphericity.[11]It was launched January 25, 1964, on aThor Agenarocket.

Ranger program (1961–1965)[edit]

The Ranger program was a series ofuncrewed space missionsby the United States in the 1960s whose objective was to obtain the first close-up images of the surface of theMoon.The Ranger spacecraft were designed to take images of the lunar surface, returning those images until they were destroyed upon impact. A series of mishaps, however, led to the failure of the first five flights.[12]Congress launched an investigation into "problems of management" at NASA Headquarters and JPL.[13]After reorganizing the organization twice,Ranger 7successfully returned images in July 1964, followed by two more successful missions.

Ranger was originally designed, beginning in 1959, in three distinct phases, called "blocks." Each block had different mission objectives and progressively more advanced system design. TheJPLmission designers planned multiple launches in each block, to maximize the engineering experience and scientific value of the mission and to assure at least one successful flight.[14]Total research, development, launch, and support costs for the Ranger series of spacecraft (Rangers 1 through 9) was approximately $170 million.[15]

Telstar (1962–1963)[edit]

Telstar was not a NASA program but rather a commercial communication satellite project. NASA's contributions to it were limited to launch services, as well as tracking and telemetry duties. The first two Telstar satellites were experimental and nearly identical. Telstar 1 was launched on top of aThor-Deltarocket on July 10, 1962. It successfully relayed through space the first television pictures, telephone calls, andfaximages, as well as providing the first live transatlantic television feed. Telstar 2 was launched May 7, 1963.[11]

Bell Telephone Laboratoriesdesigned and built the Telstar satellites. They were prototypes intended to prove various concepts behind the large constellation of orbiting satellites. Bell Telephone Laboratories also developed much of the technology required for satellite communication, includingtransistors,solar cells,andtraveling wave tubeamplifiers.AT&Tbuilt ground stations to handle Telstar communications.[11]

Mariner program (1962–1973)[edit]

The Mariner program conducted by NASA launched a series ofroboticinterplanetary probesdesigned to investigateMars,VenusandMercury.The program included a number of firsts, including the firstplanetary flyby,[16]the first pictures from another planet, the first planetaryorbiter,[17]and the first interplanetarygravity assistmaneuver,[18]which spent more than 13 years in orbit aroundSaturn.

All Mariner spacecraft were based on a hexagonal or octagonal "bus", which housed all of the electronics, and to which all components were attached, such as antennae, cameras, propulsion, and power sources. All probes exceptMariner 1,Mariner 2andMariner 5had TV cameras. The first five Mariners were launched onAtlas-Agenarockets,while the last five used theAtlas-Centaur.

Lunar Orbiter program (1966–1967)[edit]

The Lunar Orbiter program was a series of fiveuncrewedlunarorbiter missions launched by theUnited States,starting in 1966. It was intended to help select landing sites for theApollo programby mapping the Moon's surface.[19]The program produced the first photographs ever taken from lunar orbit.

All five missions were successful, and 99% of the Moon was mapped from photographs taken with a resolution of 60 meters (200 ft) or better. The first three missions were dedicated to imaging 20 potential human lunar landing sites, selected based on Earth-based observations. These were flown at low inclination orbits. The fourth and fifth missions were devoted to broader scientific objectives and were flown in high-altitude polar orbits.[20]All Lunar Orbiter craft were launched by anAtlas-AgenaD launch vehicle.

During the Lunar Orbiter missions, the first pictures of Earth as a whole were taken, beginning with Earth-rise over the lunar surface by Lunar Orbiter 1 in August 1966. The first full picture of the whole Earth was taken by Lunar Orbiter 5 on August 8, 1967.[21]A second photo of the whole Earth was taken by Lunar Orbiter 5 on November 10, 1967.

Surveyor program (1966–1968)[edit]

The Surveyor Program was a NASA program that, from 1966 through 1968, sent sevenrobotic spacecraftto the surface of theMoon.Its primary goal was to demonstrate the feasibility of softlandingson the Moon. The program was implemented by NASA'sJet Propulsion Laboratory(JPL) to prepare for theApollo program.[22]The total cost of the Surveyor program was officially $469 million.[23]

Five of the Surveyor craft successfully soft-landed on the Moon. Two failed: Surveyor 2 crashed at high velocity after a failed mid-course correction, and Surveyor 4 was lost for contact 2.5 minutes before its scheduled touch-down.[22]

All seven spacecraft are still on the Moon; none of the missions included returning them to Earth. Some parts ofSurveyor 3were returned to Earth by the crew ofApollo 12,which landed near it in 1969.

Helios probes (1974–1976)[edit]

Helios I and Helios II, also known as Helios-A and Helios-B, were a pair of space probes launched intoheliocentric orbitfor the purpose of studyingsolarprocesses. A joint venture of theFederal Republic of Germany(West Germany) and NASA, the probes were launched fromCape Canaveral Air Force Station,Florida, on December 10, 1974, and January 15, 1976, respectively. Helios 2 set a maximum speed record among spacecraft at about 247,000 kilometers per hour (153,000 mph) relative to the Sun (68.6 kilometers per second (42.6 mi/s) or 0.000229c).[24]The Helios space probes completed their primary missions by the early 1980s, but they continued to send data up to 1985. The probes are no longer functional but still remain in their elliptical orbit around the Sun.

Viking program (1975)[edit]

The Viking program consisted of a pair of American space probes sent to Mars—Viking 1andViking 2.Each vehicle was composed of two main parts, an orbiter designed to photograph the surface of Mars fromorbit,and a lander designed to study the planet from the surface. The orbiters also served as communication relays for the landers once they touched down.Viking 1waslaunchedon August 20, 1975, and the second craft,Viking 2,was launched on September 9, 1975, both riding atopTitan III-Erockets withCentaurupper stages.[25][26]By discovering many geological forms that are typically formed from large amounts of water, the Viking program caused a revolution in scientific ideas aboutwater on Mars.

The primary objectives of the Viking orbiters were to transport the landers to Mars, perform reconnaissance to locate and certify landing sites, act as communications relays for the landers, and to perform their own scientific investigations. The orbiter, based on the earlierMariner 9spacecraft, was anoctagonapproximately 2.5 m (8.2 ft) across. The total launch mass was 2,328 kilograms (5,132 lb), of which 1,445 kilograms (3,186 lb) were propellant and attitude control gas.[25]

Voyager program (1977–present)[edit]

The Voyager program consists of a pair of uncrewed scientificprobes,Voyager 1andVoyager 2.They were launched in 1977 to take advantage of a favorable planetary alignment of the late 1970s. Although they were originally designated to study justJupiterandSaturn,Voyager 2was able to continue to Uranus and Neptune. Both missions have gathered large amounts of data about thegas giantsof theSolar System,of which little was previously known.[27]Both probes have achieved escape velocity from the Solar System and will never return.Voyager 1enteredinterstellar spacein 2012.[28]

As of January 19, 2019[update],Voyager 1was at a distance of 145.148AU(13.492 billion miles (21.713×109km)) from Earth, traveling away from theSunat a speed of about 10.6 mi/s (17.1 km/s), which corresponds to a greaterspecific orbital energythan any other probe.[29]

High Energy Astronomy Observatory 1 (1977)[edit]

The first ofNASA's three High Energy Astronomy Observatories, HEAO 1, launched August 12, 1977, aboard anAtlas rocketwith aCentaurupper stage, operated until January 9, 1979. During that time, it scanned theX-raysky almost three times over 0.2 keV – 10 MeV, provided nearly constant monitoring of X-ray sources near the ecliptic poles, as well as more detailed studies of a number of objects through pointed observations.[30]

HEAO included four large X-ray and gamma-ray astronomy instruments, known as A1, A2, A3, and A4, respectively (before launch, HEAO 1 was known as HEAO A). The orbital inclination was about 22.7 degrees.[31]HEAO 1re-entered the Earth's atmosphereon March 15, 1979.

Solar Maximum Mission (1980)[edit]

The Solar Maximum Missionsatellite(or SolarMax) was designed to investigate solar phenomena, particularlysolar flares.It was launched on February 14, 1980.

Although not unique in this endeavor, the SMM was notable in that its useful life compared with similarspacecraftwas significantly increased by the direct intervention of a human space mission. DuringSTS-41-Cin 1984, theSpace ShuttleChallengerintercepted the SMM, maneuvering it into the shuttle's payload bay for maintenance and repairs. SMM had been fitted with a shuttle "grapple fixture" so that the shuttle'srobot armcould grab it for repair.[32]

The Solar Maximum Mission ended on December 2, 1989, when the spacecraft re-entered the atmosphere and burned up.[33]

Infrared Astronomical Satellite (1983)[edit]

The Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) was the first-ever space-basedobservatoryto perform asurveyof the entireskyatinfraredwavelengths.[34]It discovered about 350,000 sources, many of which are still awaiting identification. New discoveries included a dust disk aroundVegaand the first images of theMilky Way Galaxy'score.

IRAS's life, like those of most infrared satellites that followed it, was limited by its cooling system. To effectively work in the infrared domain, the telescope must be cooled to cryogenic temperatures.Superfluidheliumkept IRAS at a temperature of 2kelvins(about −271 °C) byevaporation.[35]The supply of liquid helium was depleted on November 21, 1983, preventing further observations.[36]The spacecraft continues to orbit close to the Earth.

The telescope was a joint project of the United States (NASA), theNetherlands(NIVR), and the United Kingdom (SERC). Over 250,000 infrared sources were observed at 12, 25, 60, and 100 micrometer wavelengths.[37]

Magellan probe (1989–1994)[edit]

The Magellan spacecraft was a space probe sent to the planet Venus, the first uncrewed interplanetary spacecraft to be launched by NASA since its successfulPioneer Orbiter,also to Venus, in 1978. It was also the first deep-space probe to be launched on the Space Shuttle.[38]In 1993, it employedaerobrakingtechniques to lower its orbit. This was the first prolonged use of the technique, which had been tested byHitenin 1991.[39]

Magellan created the first (and currently the best) high-resolution mapping of the planet's surface features. Prior Venus missions had created low-resolution radar globes of general, continent-sized formations. Magellan, performed detailed imaging and analysis of craters, hills, ridges, and other geologic formations, to a degree comparable to the visible-light photographic mapping of other planets.

Galileo(1989–2003)[edit]

Galileowas an uncrewed spacecraft sent by NASA to study the planetJupiterand itsmoons.It was launched on October 18, 1989, by theSpace ShuttleAtlantison theSTS-34mission. It arrived at Jupiter on December 7, 1995, viagravitational assistflybys of Venus and Earth.[40]

Despite antenna problems,Galileoconducted the firstasteroidflyby, discovered the firstasteroid moon,was the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter, and launched the first probe into Jupiter'satmosphere.Galileo's prime mission was a two-year study of the Jovian system. The spacecraft traveled around Jupiter in elongatedellipses,each orbit lasting about two months. The differing distances from Jupiter afforded by these orbits allowedGalileoto sample different parts of the planet's extensivemagnetosphere.The orbits were designed for close up flybys of Jupiter's largest moons. OnceGalileo's prime mission was concluded, an extended mission followed starting on December 7, 1997; the spacecraft made a number of close flybys of Jupiter's moonsEuropaandIo.[40]

On September 21, 2003,Galileo's mission was terminated by sending the orbiter into Jupiter's atmosphere at a speed of nearly 50 kilometers per second. The spacecraft was low on propellant; another reason for its destruction was to avoid contamination of local moons, such as Europa, with bacteria from Earth.[41]

Hubble Space Telescope (1990–present)[edit]

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is aspace telescopethat was carried intoorbitby a Space Shuttle in April 1990. It is named after AmericanastronomerEdwin Hubble.Although not the first space telescope, Hubble is one of the largest and most versatile, and is well known as both a vital research tool and a public relations boon forastronomy.The HST is a collaboration between NASA and theEuropean Space Agency,and is one of NASA'sGreat Observatories,along with theCompton Gamma Ray Observatory,theChandra X-ray Observatory,and theSpitzer Space Telescope.[42]The HST's success has paved the way for greater collaboration between the agencies.

The HST was created with a budget of $2 billion[43]and has continued operation since 1990, delighting both scientists and the public. Some of its images, such as theHubble Deep Field,have become famous.

Ulysses(1990–2009)[edit]

Ulyssesis a decommissionedroboticspace probethat was designed to study theSunas a joint venture of NASA and theEuropean Space Agency(ESA).Ulysseswas launched on October 6, 1990, aboardDiscovery(missionSTS-41). The spacecraft's mission was to study the Sun at all latitudes. This required a major orbital plane shift, which was accomplished by using an encounter with Jupiter. The need for a Jupiter encounter meant thatUlyssescould not be powered by solar cells and was powered by aradioisotope thermoelectric generator(RTG) instead.[44]

By February 2008, the power output from theRTG,which is generated by heat from radioactive decay, had decreased enough to leave insufficient power to keep the spacecraft'sattitude controlhydrazine fuel from freezing. Mission scientists kept the fuel liquid by conducting short thruster burns, allowing the mission to continue.[45][46][47]The cessation of mission operations and deactivation of the spacecraft was determined by the inability to prevent attitude control fuel from freezing.[45][48]The last day for mission operations onUlysseswas June 30, 2009.[49][50]

Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (1991)[edit]

The Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) was a science satellite used from 1991 to 2005 to study Earth's atmosphere, including theozone layer.Planned for a three-year mission, it proved much more durable, allowing extended observation from its instrument suite. It was launched aboardSpace ShuttleDiscoveryand deployed into space from the payload bay with its robotic arm, under guidance from the crew. The satellite underwent atmospheric re-entry at about 04:00 24 September 2011UTC.[51]At about 6 tonnes, it was the heaviest NASA satellite to undergo uncontrolled atmospheric entry sinceSkylabin the summer of 1979.[52]

Discovery Program (1992–present)[edit]

NASA's Discovery Program (as compared toNew FrontiersorFlagshipPrograms) is a series of lower-cost, highly focused scientific space missions that are exploring the Solar System. It was founded in 1992 to implement then-NASA AdministratorDaniel S. Goldin's vision of "faster, better, cheaper" planetary missions. Discovery missions differ from traditional NASA missions where targets and objectives are pre-specified. Instead, these cost-capped missions are proposed and led by a scientist called thePrincipal investigator(PI). Proposing teams may include people from industry, small businesses, government laboratories, and universities. Proposals are selected through a competitive peer review process. The Discovery missions are adding significantly to the body of knowledge about the Solar System.

NASA also accepts proposals for competitively selected Discovery Program Missions of Opportunity. This provides opportunities to participate in non-NASA missions by providing funding for a science instrument or hardware components of a science instrument or to re-purpose an existing NASA spacecraft.

Missions funded by NASA through this program includeMars Pathfinder,Kepler,Stardust,GenesisandDeep Impact.

TheMars Pathfinder(MESUR Pathfinder[53]) was launched on December 4, 1996, just a month after the Mars Global Surveyor was launched. On board thelander,later renamed the Carl Sagan Memorial Station, was a smallrovercalledSojournerthat executed many experiments on the Martian surface.[54]It was the second project from NASA'sDiscovery Program.The mission was directed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of theCalifornia Institute of Technology,responsible for NASA'sMars Exploration Program.

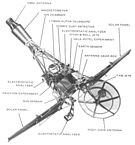

Stardustwas a 300-kilogramroboticspace probelaunched by NASA on February 7, 1999, to study theasteroid5535 Annefrankand collect samples from thecomaofcometWild 2.The primary mission was completed January 15, 2006, when thesample returncapsule returned to Earth.[55]Stardust intercepted cometTempel 1on February 15, 2011, asmall Solar System bodypreviously visited byDeep Impacton July 4, 2005. Stardust was decommissioned on March 25, 2011.[56]It is the firstsample return missionto collectcosmic dust.

TheGenesis spacecraftwas a NASAsample returnprobe which collected a sample ofsolar windand returned it toEarthfor analysis. It was the first NASA sample return mission to return material since theApollo Program,and the first to return material from beyond the orbit of theMoon.[57]Genesis was launched on August 8, 2001, and crash-landed inUtahon September 8, 2004, after a design flaw prevented the deployment of itsdrogue parachute.[58]The crash contaminated and damaged many of the sample collectors, but many of them were successfully recovered.[59]

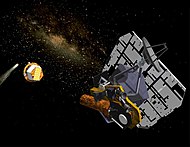

Deep Impact is a NASAspace probelaunched on January 12, 2005. It was designed to study the composition of the interior of comet9P/Tempel,by releasing an impactor into the comet. On July 4, 2005, the impactor successfully collided with the comet'snucleus,excavating debris from the interior of the nucleus. Photographs of the debris and impact crater showed that the comet was very porous and its outgassing was chemically diverse.[60]

Kepler is aspace observatorylaunched by NASA to discoverEarth-like planetsorbiting other stars. The spacecraft, named in honor of the 17th-century German astronomerJohannes Kepler,[61]was launched in March 2009.[62]Kepler's primary mission ended in May 2013 when it lost a secondreaction wheel.The telescope's second mission, K2, began in May 2014.[63]As of February 2018, Kepler has discovered more than 2000 exoplanets.[64]

Clementine(1994)[edit]

Clementine(officially called the Deep Space Program Science Experiment (DSPSE)) was a joint space project between theBallistic Missile Defense Organization(BMDO, previously theStrategic Defense Initiative Organization,or SDIO) and NASA. Launched on January 25, 1994, the objective of the mission was to test sensors and spacecraft components under extended exposure to the space environment and to make scientific observations of theMoonand thenear-Earth asteroid1620 Geographos.The Geographos observations were not made due to a malfunction in the spacecraft.[65]

Mars Global Surveyor (1996)[edit]

TheMars Global Surveyor(MGS) was developed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and launched November 1996. It began the United States' return to Mars after a 10-year absence. It completed its primary mission in January 2001 and was in its third extended mission phase when, on November 2, 2006, the spacecraft failed to respond to commands. In January 2007 NASA officially ended the mission.[66]

TheSurveyorspacecraft used a series of high-resolution cameras to explore the surface of Mars, returning more than 240,000 images from September 1997 to November 2006.[67]The surveyor had three cameras; a high-resolution camera took black-and-white images (usually 1.5 to 12 m per pixel), and red and blue wide-angle cameras took images for context (240 m per pixel) and daily global images (7.5 kilometers (4.7 mi) per pixel).[68]

Cassini–Huygens(1997–2017)[edit]

Cassini–Huygenswas a joint NASA/ESA/ASIspacecraft mission studying the planetSaturnand its manynatural satellites.It included a Saturn orbiter and an atmospheric probe/lander for the moonTitan,although it also returned data on a wide variety of other things including theHeliosphere,Jupiter,andrelativity tests.The Titan probe,Huygens,entered and landed on Titan in 2005.Cassiniwas the fourth space probe to visit Saturn and the first to enter orbit.

It launched on October 15, 1997, on aTitan IVB/Centaur and entered into orbit around Saturn on July 1, 2004, after an interplanetary voyage which included flybys of Earth, Venus, and Jupiter. On December 25, 2004,Huygensseparated from the orbiter at approximately 02:00UTC.It reached Saturn's moonTitanon January 14, 2005, when it entered Titan's atmosphere and descended down to the surface. It successfully returned data to Earth, using the orbiter as a relay.[69]This was the firstlandingever accomplished in theouter Solar System.

Sixteen European countries and the United States made up the team responsible for designing, building, flying and collecting data from theCassiniorbiter and Huygens probe. The mission was managed by NASA'sJet Propulsion Laboratoryin the United States, where the orbiter was assembled.Huygenswas developed by theEuropean Space Research and Technology Centre.[70]

After several mission extensions,Cassiniwas deliberately plunged into Saturn's atmosphere on September 15, 2017, to prevent contamination of habitable moons.[71]

Earth Observing System (1997–present)[edit]

The Earth Observing System (EOS) is a program ofNASAcomprising a series ofartificial satellitemissions and scientific instruments inEarthorbitdesigned for long-term global observations of the land surface,biosphere,atmosphere,and oceans of the Earth. The satellite component of the program was launched in 1997. The program is the centerpiece of NASA'sEarth Science Enterprise(ESE). Missions carried out through this program includeSeaWiFS(1997),Landsat 7(1999),QuikSCAT(1999),Jason 1(2001),GRACE(2002),Aqua(2002),Aura(2004) andAquarius(2011).

New Millennium Program (1998–2006)[edit]

New Millennium Program (NMP) is a NASA project with a focus on engineering validation of new technologies for space applications. Funding for the program was eliminated from the FY2009 budget by the110th United States Congress,effectively leading to its cancellation.[72]The spacecraft in the New Millennium Program were originally named "Deep Space" (for missions demonstrating technology for planetary missions) and "Earth Observing" (for missions demonstrating technology for Earth-orbiting missions). With a refocusing of the program in 2000, the Deep Space series was renamed "Space Technology."

Deep Space 1(DS1) is aspacecraftdedicated to testing a payload of advanced, high-risk technologies. Launched on October 24, 1998, the Deep Space 1 mission carried out a flyby ofasteroid9969 Braille,the mission's science target. Its mission was extended twice to include an encounter withComet Borrellyand further engineering testing. Problems during its initial stages and with its star tracker led to repeated changes in mission configuration.[73]Deep Space 1 tested twelve technologies.[74]It was the first spacecraft to useion thrusters,in contrast to the traditional chemical powered rockets.[75]

The Deep Space series was continued by theDeep Space 2probes, which were launched in January 1999 onMars Polar Landerand were intended to strike the surface of Mars.

Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (2002)[edit]

The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE), a joint mission of NASA and theGerman Aerospace Center,made detailed measurements ofEarth's gravityfield from its launch in March 2002 until October 2017.[76]The satellites were launched fromPlesetsk Cosmodrome,Russia on aRockotlaunch vehicle. By measuring gravity, GRACE showed how mass is distributed around the planet and how it varies over time. Data from the GRACE satellites is an important tool for studying Earth's ocean, geology, andclimate.[77]

GRACE was a collaborative endeavor involving the Center for Space Research at theUniversity of Texas, Austin;NASA'sJet Propulsion Laboratory,Pasadena, Calif.; the German Space Agency and Germany's National Research Center for Geosciences, Potsdam.[78]The Jet Propulsion Laboratory was responsible for the overall mission management under the NASA ESSP program.[79]

Mars Exploration Rover (2003–2019)[edit]

NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Mission (MER), was a robotic space mission involving two rovers exploring the planet Mars. The mission is managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which designed, built and is operating the rovers.

The mission began in 2003 with the sending of the tworovers—MER-ASpiritand MER-BOpportunity—to explore the Martian surface and geology. The mission's scientific objective is to search for and studyrocksandsoilsthat indicate past water activity. The mission is part of NASA's Mars Exploration Program which includes three previous successful landers: the twoViking programlanders in 1976 andMars Pathfinderprobe in 1997.[80]

The total cost of building, launching, landing and operating the rovers on the surface for the initial 90-Martian-day (sol)primary mission was US$820 million.[81]However, both rovers were able to continue functioning beyond the initial 90-day mission, and received multiple mission extensions. TheSpiritrover remained operational until 2009, while theOpportunityrover remained operational until 2018.

MESSENGER(2004–2015)[edit]

MESSENGER(an acronym of MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) was a robotic spacecraft that orbited the planetMercury,the first spacecraft to do so.[82]The 485-kilogram (1,069 lb) spacecraft was launched aboard aDelta IIrocket in August 2004 to study Mercury's chemical composition,geology,andmagnetic field.

MESSENGERused its instruments on a complex series offlybysthat allowed it to decelerate relative to Mercury using minimal fuel. The spacecraft flew by Earth once andVenustwice. Then it flew by Mercury three times, in January 2008, October 2008,[83]and September 2009,[84][85]becoming the second mission to reach Mercury, afterMariner 10.MESSENGERentered orbit around Mercury on March 18, 2011, and it reactivated its science instruments on March 24, returning the first photo from Mercury orbit on March 29.

MESSENGERcrashed into Mercury on April 30, 2015, after running out of propellant.[86]

New Frontiers program (2006–present)[edit]

The New Frontiers program is a series of space exploration missions being conducted by NASA with the purpose of researching several of theSun's planets includingJupiter,Venus,and thedwarf planetPluto.NASA is encouraging both domestic and international scientists to submit mission proposals for the project.

New Frontiers was built on the approach used by theDiscoveryandExplorerPrograms ofprincipal investigator-led missions. It is designed for medium-class missions that could not be accomplished within the cost and time constraints of the Discovery Program, but are not as large as Flagship-class missions. There are currently three New Frontiers missions in progress.New Horizonswas launched on January 19, 2006, and flew by Pluto in July 2015. A flyby of486958 Arrokothtook place in 2019.[87]Junowas launched on August 5, 2011, and entered orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016.[88]OSIRIS-REx,launched on September 8, 2016, plans on returning a sample to Earth on September 24, 2023,[89]and if successful, would be the first U.S. spacecraft to do so.

Commercial Resupply Services (2006–present)[edit]

The development of theCommercial Resupply Services(CRS) vehicles began in 2006 with the purpose of creating American commercially operated uncrewed cargo vehicles to service the ISS.[90]The development of these vehicles was under a fixed-price, milestone-based program, meaning that each company that received a funded award had a list of milestones with a dollar value attached to them that they did not receive until after they had successfully completed the milestone.[91]Companies were also required to raise an unspecified amount of private investment for their proposal.[92]

On December 23, 2008, NASA awarded Commercial Resupply Services contracts toSpaceXandOrbital Sciences Corporation.[93]SpaceX uses itsFalcon 9 rocketandDragon spacecraft.[94]Orbital Sciences uses itsAntaresrocket andCygnus spacecraft.Thefirst Dragon resupply missionoccurred in May 2012.[95]Thefirst Cygnus resupply missionoccurred in September 2013.[96]The CRS program now provides for all America's ISS cargo needs, with the exception of a few vehicle-specific payloads that are delivered on the EuropeanATVand the JapaneseHTV.[97]

Mars Scout Program (2007–2008)[edit]

The Mars Scout Program was aNASAinitiative to send a series of small, low-cost robotic missions toMars,competitively selected from proposals by the scientific community. Each Scout project was to cost less than US$485 million. ThePhoenixlander andMAVENorbiter were selected and developed before the program was retired in 2010.[98]

Phoenixwas alanderadapted from the canceledMars Surveyormission.Phoenixwas launched on August 4, 2007, and landed in the icy northern polar region of the planet on May 25, 2008. Phoenix was designed to search for environments suitable formicrobiallife on Marsand to research the history ofwater there.[99]The 90-day primary mission was successful, and the overall mission was concluded on November 10, 2008, after engineers were unable to contact the craft. The lander last made a brief communication with Earth on November 2, 2008.[100]

Dawn(2007–2018)[edit]

Dawnis a NASA spacecraft tasked with the exploration and study of theasteroidVestaand thedwarf planetCeres,the two largest members of theasteroid belt.The spacecraft was constructed with some European cooperation, with components contributed by partners in Germany, Italy, and theNetherlands.TheDawnmission is managed by NASA'sJet Propulsion Laboratory.[101]

Dawnis the first spacecraft to visit either Vesta or Ceres. It is also the first spacecraft to orbit two separate extraterrestrial bodies, usingion thrustersto travel between its targets. Previous multi-target missions using conventional drives, such as theVoyagerprogram,were restricted toflybys.[102]

Launched on September 27, 2007,Dawnentered orbit around Vesta on July 16, 2011, and explored it until September 5, 2012.[103]Thereafter, the spacecraft headed to Ceres and started to orbit the dwarf planet on March 6, 2015.[104]In November 2018, NASA reported thatDawnhad run out of fuel, effectively ending its mission; it will remain in orbit around Ceres, but can no longer communicate with Earth.[105]

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (2009–present)[edit]

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) is a NASArobotic spacecraftcurrently orbiting theMoonon a low50 kmpolar mapping orbit.[106] The LRO mission is a precursor to future human missions to the Moon by NASA. To this end, a detailed mapping program identifies safe landing sites, locates potential resources on the Moon, characterizes the radiation environment, and demonstrates new technology.[107][108] The probe has made a 3-D map of the Moon's surface and has provided some of the first images of Apollo equipmentleft on the Moon.[109][110] The first images from LRO were published on July 2, 2009, showing a region in the lunar highlands south ofMare Nubium(Sea of Clouds).[111]

Launched on June 18, 2009,[112]in conjunction with theLunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite(LCROSS), as the vanguard of NASA'sLunar Precursor Robotic Program,[113]this is the first United States mission to the Moon in over ten years.[114] LRO and LCROSS are the first missions launched as part of the United States'sVision for Space Explorationprogram.

In April 2022, NASA extended the LRO mission for it to continue to study the Moon's surface and geologic features and also investigate new regions enabled with the evolution of LRO's orbit[115]

Mars Science Laboratory (2011–present)[edit]

Mars Science Laboratory(MSL) is a NASA mission to land and operate arovernamedCuriosityon the surface ofMars.[116]It was launched by anAtlas Vrocket on November 26, 2011,[117][118]and landed successfully on August 6, 2012, on the plains ofAeolis PalusinGale CraternearAeolis Mons(formerlyMount Sharp).[119][120][121][122]On Mars, it is helping to assess Mars'habitability.It can chemically analyze samples by scooping up soil and drillingrocksusing a laser and sensor system.[123]

TheCuriosityrover is about two times longer and fives times more massive than theSpiritorOpportunityMars Exploration Rovers[123]and carries more than ten times the mass of scientific instruments.[118]

Mars 2020 (2020–present)[edit]

Mars 2020 is aMars rovermission byNASA'sMars Exploration Programthat includes thePerseverancerover which launched on 30 July 2020 at 11:50 UTC, and has touched down inJezero crateron Mars on 18 February 2021 and deployed theIngenuityhelicopter on 4 April 2021.[124][125]It will investigate anastrobiologicallyrelevant ancient environment on Mars and investigate its surfacegeological processesand history, including the assessment of its pasthabitability,the possibility of pastlife on Mars,and the potential for preservation ofbiosignatureswithin accessible geological materials.[126][127]It will cache sample containers along its route for a potential futureMars sample-return mission.[127][128][129]The Mars 2020 mission was announced by NASA on 4 December 2012 at the fall meeting of theAmerican Geophysical Unionin San Francisco.[130]ThePerseverancerover's design is derived from theCuriosityrover,and will use many components already fabricated and tested, new scientific instruments and acore drill.[131]

Commercial Lunar Payload Services (2023-present)[edit]

Commercial Lunar Payload Services(CLPS) is aNASAprogram to hire companies to send small robotic landers and rovers to theMoon'ssouth polar region,mostly[132][133]with the goals of scouting forlunar resources,testingin situ resource utilization(ISRU) concepts, and performing lunar science to support theArtemis lunar program.CLPS is intended to buy end-to-end payload services between Earth and the lunar surface usingfixed-price contracts.[134]The program was extended to add support for large payloads starting after 2025.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"NASA history"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on October 19, 2011.RetrievedJuly 12,2017.

- ^Brown, Katherine (March 24, 2017)."NASA Selects Mission to Study Churning Chaos of Nearby Cosmos".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 8, 2019.RetrievedJune 9,2019.

- ^ Clayton Koppes, "JPL and the American Space Program", (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982); Erik M. Conway, "From Rockets to Spacecraft: Making JPL a Place for Planetary Science",Engineering and Science, vol. 30, nr. 4, pp. 2–10.ArchivedMarch 22, 2014, at theWayback Machine.

- ^Dickson, Paul (2001).Sputnik: The Launch of the Space Race.MacFarlane Walter & Ross. p. 190.ISBN9781551990873.

- ^"The Pioneer Missions".NASA. March 3, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on January 22, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 26,2018.

- ^"Pioneer Venus 1, Orbiter and Multiprobe spacecraft (included NASA Ames partnership)".NASA. March 23, 2007.Archivedfrom the original on May 7, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 17,2018.

- ^"Echo 1, 1A, 2 Quicklook".Mission and Spacecraft Library.NASA. Archived fromthe originalon May 27, 2010.RetrievedFebruary 6,2010.

- ^ "Astronautix, Echo".Archived fromthe originalon May 11, 2008.RetrievedOctober 21,2011.

- ^"Echo 1".NASA.RetrievedJuly 13,2010.

- ^Martin, Donald H. (2000).Communication Satellites(4 ed.). AIAA. p. 4.ISBN9781884989094.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 27,2018.

- ^abc Chapter 6, NASA Experimental Communications Satellites, 1958–1995ArchivedAugust 4, 2011, at theWayback Machine.Retrieved October 23, 2011

- ^"Cortright Oral History (p25)"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on September 10, 2012.RetrievedMay 12,2012.

- ^Dick, Steven J., ed. (2010).NASA's First 50 Years: Historical Perspectives(PDF).NASA. p. 12.ISBN978-0-16-084965-7.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on December 25, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 15,2018.

- ^"Rangers and Surveyors to the Moon"(PDF).NASA.Archived(PDF)from the original on May 25, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 25,2018.

- ^"Ranger 1".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedFebruary 25,2018.

- ^"Mariner 2".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedMarch 18,2018.

- ^"Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars"(PDF).NASA.Archived(PDF)from the original on May 25, 2018.RetrievedMarch 18,2018.

- ^"Mariner 10".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedMarch 18,2018.

- ^ Bowker, David E. and J. Kenrick Hughes, Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon[1]ArchivedMarch 3, 2016, at theWayback Machine,NASA SP-206 (1971).

- ^"Lunar Orbiter (1966–1967)".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on May 29, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 25,2018.

- ^"Whole Earth".Lunar Orbiter V.NASA. August 8, 1967. p. 352.Archivedfrom the original on December 25, 2017.RetrievedDecember 24,2008.

Clearly visible on the left side of the globe is the eastern half of Africa and the entire Arabian peninsula.

- ^ab"The Surveyor Program".Lunar and Planetary Institute.Archivedfrom the original on December 13, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 19,2018.

- ^"Surveyor 1".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedFebruary 19,2018.

- ^"Fastest spacecraft speed".Guinness World Records.Archivedfrom the original on December 19, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 28,2018.

- ^ab"Viking 1 Orbiter".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedFebruary 25,2018.

- ^"Viking 2 Orbiter".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedFebruary 25,2018.

- ^"Planetary Voyage".Voyager.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 26,2018.

- ^"Interstellar Mission".Voyager.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on September 14, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 26,2018.

- ^"Voyager – Mission Status".Jet Propulsion Laboratory.NASA. Archived fromthe originalon June 28, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 19,2019.

- ^"The HEAO-1 Satellite".HEASARC.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on April 20, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 16,2018.

- ^"HEAO-1".HEASARC.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 16,2018.

- ^Guillermier, Pierre; Koutchmy, Serge (1999).Total Eclipses: Science, Observations, Myths and Legends.Springer. pp.27–28.ISBN9781852331603.RetrievedFebruary 16,2018.

- ^"Solar Maximum Mission (SMM) | High Altitude Observatory".www2.hao.ucar.edu.Archivedfrom the original on April 23, 2019.RetrievedJune 13,2019.

- ^ IRAS Explanatory Supplement II. Satellite DescriptionArchivedApril 13, 2012, at theWayback MachineIPAC IRAS archive

- ^"Cryogenics".IRSA.NASA/IPAC.Archivedfrom the original on January 24, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 26,2018.

- ^"Infrared Astronomical Satellite".LAMBDA.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on September 14, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 26,2018.

- ^Schmadel, Lutz (August 5, 2003).Dictionary of Minor Planet Names.Springer Science & Business Media. p. 315.ISBN978-3-540-00238-3.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2019.RetrievedMarch 1,2016.

- ^Young, Carolynn, ed. (1990)."Chapter 2: The Magellan Mission".The Magellan Venus Explorer's Guide.JPL.

- ^Carroll, Michael (2011).Drifting on Alien Winds: Exploring the Skies and Weather of Other Worlds.Springer. p. 47.ISBN9781441969170.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 14,2018.

- ^ab"Galileo".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon February 19, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 18,2018.

- ^"Galileo ends in blaze of glory".BBC News.September 21, 2003.Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 18,2018.

- ^"NASA's Great Observatories".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on April 22, 2008.RetrievedApril 26,2008.

- ^Dunar, A. J.; S. P. Waring (1999).Power to Explore—History of Marshall Space Flight Center 1960–1990.U.S. Government Printing Office.ISBN0-16-058992-4.Chapter 12,"The Hubble Space Telescope"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on September 27, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 24,2011.(260 KB)

- ^"International Mission Studying Sun to Conclude".NASA/JPL.Archivedfrom the original on September 21, 2015.RetrievedJune 13,2019.

- ^ab"Light goes out on solar mission".BBC News.British Broadcasting Company. June 26, 2009.Archivedfrom the original on June 28, 2009.RetrievedJune 26,2009.

- ^"ESA Portal – Sun to set on Ulysses solar mission on July 1".Archivedfrom the original on March 9, 2012.RetrievedMay 12,2012.

- ^esa."Ulysses hanging on valiantly".Archivedfrom the original on March 9, 2012.RetrievedMay 12,2012.

- ^ Solar wind blows at 50-year lowArchivedApril 15, 2012, at theWayback Machine2008-09-24, Jonathan Amos, BBC News Online. Retrieved September 28, 2008

- ^"Ulysses: 12 extra months of valuable science".European Space Agency.June 30, 2009.Archivedfrom the original on March 9, 2012.RetrievedJuly 1,2009.

- ^"The odyssey concludes..."Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2012.RetrievedMay 12,2012.

- ^"Final Update: NASA's UARS Re-enters Earth's Atmosphere".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 15,2018.

- ^"Falling Satellite Re-Entry Closer: Is U.S. Safe?".ABC News. September 23, 2011.Archivedfrom the original on September 24, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 24,2011.

- ^"One Way or Another, Space Agency Will Hitch a Ride to Mars".Washington Post.November 13, 1993.

- ^"Mars Pathfinder"(PDF).NASA.Archived(PDF)from the original on May 25, 2018.RetrievedMarch 2,2018.

- ^"NASA Spacecraft Returns With Comet Samples After 2.9 Bln Miles".Bloomberg. Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedMarch 4,2008.

- ^"Stardust/NExT".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedFebruary 28,2018.

- ^The NASAStardust missionlaunched two years before Genesis, but did not return to Earth until two years after Genesis's return.

- ^"Mission History".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on December 22, 2018.RetrievedMarch 2,2018.

- ^"Solar Wind Curation at JSC".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on July 21, 2011.RetrievedMay 12,2012.

- ^"Deep Impact (EPOXI)".Solar System Exploration.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on February 4, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 24,2018.

- ^DeVore, Edna (June 9, 2008)."Closing in on Extrasolar Earths".SPACE.Archivedfrom the original on April 20, 2009.RetrievedMarch 14,2009.

- ^NASA Staff."Kepler Launch".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on May 27, 2012.RetrievedSeptember 18,2009.

- ^"Mission overview".NASA. April 13, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on March 11, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 27,2018.

- ^"Exoplanet and Candidate Statistics".NASA Exoplanet Archive.Archivedfrom the original on January 24, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 27,2018.

- ^"Clementine".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedFebruary 27,2018.

- ^"Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) Spacecraft Loss of Contact"(PDF).National Aeronautics and Space Administration.April 13, 2007.Archived(PDF)from the original on February 27, 2017.

- ^"Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC)".Malin Space Science Systems.Archivedfrom the original on January 31, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 28,2018.

- ^Malin, M. et al.Mars Global Surveyor Mars Orbiter Camera in the Extended Mission: The MOC ToolkitArchivedOctober 25, 2012, at theWayback Machine,35th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, March 15–19, 2004, League City, Texas, abstract no.1189

- ^"The mission".ESA.Archivedfrom the original on February 9, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 16,2018.

- ^"Cassini Mission to Saturn"(PDF).NASA. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on December 22, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 27,2018.

- ^Howell, Elizabeth (September 15, 2017)."Cassini-Huygens: Exploring Saturn's System".Space.Archivedfrom the original on February 7, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 13,2018.

- ^David Shiga (February 5, 2008)."NASA calls for ambitious outer solar system mission".New Scientist.Archivedfrom the original on May 1, 2015.RetrievedApril 16,2009.

- ^"Deep Space 1".NSSDCA.NASA.RetrievedFebruary 26,2018.

- ^"Mission".Jet Propulsion Laboratory.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 26,2018.

- ^"Deep Space 1".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on November 17, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 26,2018.

- ^"Prolific Earth Gravity Satellites End Science Mission".NASA/JPL. October 27, 2017.Archivedfrom the original on November 18, 2017.RetrievedMarch 15,2018.

- ^"Measuring Earth's Gravitational Field".JPL.Archivedfrom the original on October 22, 2011.RetrievedMarch 15,2018.

- ^"Grace Space Twins Set to Team Up to Track Earth's Water and Gravity".NASA/JPL. March 7, 2002.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2019.RetrievedMarch 15,2018.

- ^"Mission Overview".University of Texas. November 19, 2008. Archived fromthe originalon May 15, 2009.RetrievedJuly 30,2009.

- ^"Mars Exploration Rover Mission Overview".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on July 27, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 17,2018.

- ^"NASA extends Mars rovers' mission".NBC News. October 16, 2007.RetrievedApril 5,2009.

- ^"NASA Spacecraft Circling Mercury".New York Times.March 17, 2011.RetrievedJuly 9,2013.

- ^"Countdown to MESSENGER's Closest Approach with Mercury"(Press release). Johns Hopkins University. January 14, 2008. Archived fromthe originalon May 13, 2013.RetrievedMay 1,2009.

- ^"Critical Deep-Space Maneuver Targets MESSENGER for Its Second Mercury Encounter"(Press release). Johns Hopkins University. March 19, 2008. Archived fromthe originalon May 13, 2013.RetrievedApril 20,2010.

- ^"Deep-Space Maneuver Positions MESSENGER for Third Mercury Encounter"(Press release). Johns Hopkins University. December 4, 2008. Archived fromthe originalon May 13, 2013.RetrievedApril 20,2010.

- ^Wall, Mike (April 30, 2015)."Farewell, MESSENGER! NASA Probe Crashes into Mercury".Space.Archived fromthe originalon October 1, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 13,2018.

- ^Howell, Elizabeth."New Horizons: Exploring Pluto and Beyond".Space.Archivedfrom the original on February 19, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 19,2018.

- ^"Juno".Jet Propulsion Laboratory.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 1, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 19,2018.

- ^"OSIRIS-REx Factsheet"(PDF).NASA/Explorers and Heliophysics Projects Division. August 2011.Archived(PDF)from the original on November 8, 2018.RetrievedJanuary 29,2018.

- ^"NASA Selects Crew and Cargo Transportation to Orbit Partners"(Press release). NASA. August 18, 2006.Archivedfrom the original on October 12, 2006.RetrievedNovember 21,2006.

- ^"Moving Forward: Commercial Crew Development Building the Next Era in Spaceflight"(PDF).Rendezvous.NASA. 2010. pp. 10–17.Archived(PDF)from the original on November 24, 2010.RetrievedFebruary 14,2011.

Just as in the COTS projects, in the CCDev project we have fixed-price, pay-for-performance milestones "Thorn said." There's no extra money invested by NASA if the projects cost more than projected.

- ^McAlister, Phil (October 2010)."The Case for Commercial Crew"(PDF).NASA.Archived(PDF)from the original on April 4, 2012.RetrievedJuly 2,2012.

- ^"NASA Awards Space Station Commercial Resupply Services Contracts".NASA. December 23, 2008.Archivedfrom the original on December 2, 2017.

- ^"Space Exploration Technologies Corporation – Press".Spacex. Archived fromthe originalon July 21, 2009.RetrievedJuly 17,2009.

- ^Clark, Stephen (June 2, 2012)."NASA expects quick start to SpaceX cargo contract".SpaceFlightNow.Archivedfrom the original on June 30, 2012.RetrievedJune 30,2012.

- ^Bergin, Chris (September 28, 2013)."Orbital's Cygnus successfully berthed on the ISS".NASASpaceFlight (not affiliated with NASA).Archivedfrom the original on October 13, 2013.RetrievedOctober 17,2013.

- ^"SpaceX/NASA Discuss launch of Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon capsule".NASA. May 22, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on July 21, 2013.RetrievedJune 23,2012.

- ^Vieru, Tudor."NASA's Scout Program Discontinued".Archived fromthe originalon October 12, 2012.RetrievedJune 2,2012.

- ^"Phoenix".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on September 8, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 17,2018.

- ^Thompson, Andrea (November 10, 2008)."Mars Lander Mission Appears to be Over".Space.Archivedfrom the original on February 17, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 17,2018.

- ^Evans, Ben (October 8, 2017)."Complexity and Challenge: Dawn Project Manager Speaks of Difficult Voyage to Vesta and Ceres".AmericaSpace.Archivedfrom the original on February 24, 2018.RetrievedMarch 3,2018.

- ^Rayman, Marc; Fraschetti; Raymond; Russell (April 5, 2006)."Dawn: A mission in development for exploration of main belt asteroids Vesta and Ceres"(PDF).Acta Astronautica.58(11): 605–616.Bibcode:2006AcAau..58..605R.doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2006.01.014.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on September 30, 2011.RetrievedApril 14,2011.

- ^"Dawn has Departed the Giant Asteroid Vesta".NASA. September 5, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on October 18, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 27,2018.

- ^"NASA Spacecraft Becomes First to Orbit a Dwarf Planet".NASA. March 6, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on October 18, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 27,2018.

- ^ Northon, Karen (November 1, 2018)."NASA's Dawn Mission to Asteroid Belt Comes to End".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on November 1, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 11,2019.

- ^Where is LRO right now?,archived fromthe originalon May 16, 2012,retrievedJune 2,2012

- ^LRO Mission Overview,archivedfrom the original on July 31, 2012,retrievedOctober 3,2009

- ^"Mission design and operation considerations for NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter"(PDF).Goddard Space Flight Center.Archived(PDF)from the original on July 29, 2012.RetrievedFebruary 10,2008.

- ^ Koczor, Ron (July 11, 2005)."Abandoned Spaceships".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon August 8, 2009.RetrievedAugust 5,2009.

- ^Garner, Robert (July 17, 2009)."LROC images of Apollo sites".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on November 16, 2009.RetrievedAugust 5,2009.

- ^Garner, Robert (July 2, 2009)."LRO's First Moon Images".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on August 8, 2009.RetrievedAugust 5,2009.

- ^ "Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Launch".Goddard Space Flight Center.Archived fromthe originalon February 14, 2013.RetrievedMarch 22,2008.

- ^ Mitchell, Brian."Lunar Precursor Robotic Program: Overview & History".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon July 30, 2009.RetrievedAugust 5,2009.

- ^Dunn, Marcia (June 18, 2009)."NASA launches uncrewed Moon shot, first in decade".ABC News.Associated Press.Archived fromthe originalon June 20, 2009.RetrievedAugust 5,2009.

- ^Warren, Haygen (August 11, 2022)."Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter discovers thermally stable areas in surface pits suitable for future lunar bases".nasaspaceflight.RetrievedSeptember 8,2022.

- ^"NASA Selects Student's Entry as New Mars Rover Name".NASA/JPL. May 27, 2009.Archivedfrom the original on January 28, 2012.RetrievedMay 27,2009.

- ^Greicius, Tony (January 20, 2015)."Mars Science Laboratory – Curiosity".Archivedfrom the original on May 29, 2013.RetrievedMay 12,2012.

- ^ab"NASA Launches Most Capable and Robust Rover To Mars".Mars Exploration Program.NASA. November 26, 2011.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2019.RetrievedMarch 5,2018.

- ^NASA Staff (August 6, 2012)."Curiosity's Daily Update: Curiosity Safely on Mars! Health Checks Begin".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon August 9, 2012.RetrievedAugust 12,2012.

- ^Agle, D. C. (March 28, 2012)."'Mount Sharp' On Mars Links Geology's Past and Future ".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 31, 2012.RetrievedMarch 31,2012.

- ^Staff (March 29, 2012)."NASA's New Mars Rover Will Explore Towering 'Mount Sharp'".Space.Archivedfrom the original on March 30, 2012.RetrievedMarch 30,2012.

- ^USGS (May 16, 2012)."Three New Names Approved for Features on Mars".USGS.Archivedfrom the original on October 17, 2017.RetrievedMay 20,2012.

- ^ab"Mars Science Laboratory/Curiosity"(PDF).NASA.Archived(PDF)from the original on February 1, 2017.RetrievedMarch 5,2018.

- ^Chang, Kenneth (November 19, 2018)."NASA Mars 2020 Rover Gets a Landing Site: A Crater That Contained a Lake – The rover will search the Jezero Crater and delta for the chemical building blocks of life and other signs of past microbes".The New York Times.RetrievedNovember 21,2018.

- ^Wall, Mike (November 19, 2018)."Jezero Crater or Bust! NASA Picks Landing Site for Mars 2020 Rover".Space.RetrievedNovember 20,2018.

- ^Chang, Alicia (July 9, 2013)."Panel: Next Mars rover should gather rocks, soil".Associated Press.RetrievedJuly 12,2013.

- ^abSchulte, Mitch (December 20, 2012)."Call forLetters of Applicationfor Membership on the Science Definition Team for the 2020 Mars Science Rover "(PDF).NASA. NNH13ZDA003L.

- ^"Summary of the Final Report"(PDF).NASA / Mars Program Planning Group. September 25, 2012. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on October 20, 2020.RetrievedMarch 28,2021.

- ^Moskowitz, Clara (February 5, 2013)."Scientists Offer Wary Support for NASA's New Mars Rover".SPACE.RetrievedFebruary 5,2013.

- ^Harwood, William (December 4, 2012)."NASA announces plans for new US$1.5 billion Mars rover".CNET.RetrievedDecember 5,2012.

Using spare parts and mission plans developed for NASA's Curiosity Mars rover, the space agency says it can build and launch the rover in 2020 and stay within current budget guidelines.

- ^Amos, Jonathan (December 4, 2012)."Nasa to send new rover to Mars in 2020".BBC News.RetrievedDecember 5,2012.

- ^NASA taps 3 companies for commercial moon missionsArchivedFebruary 26, 2020, at theWayback Machine.William Harwood,CBS News.31 May 2019.

- ^Foust, Jeff (May 31, 2019)."NASA awards contracts to three companies to land payloads on the moon".Space News.RetrievedNovember 26,2022.

- ^"NASA Expands Plans for Moon Exploration: More Missions, More Science".NASA. April 30, 2018.Archivedfrom the original on February 16, 2020.RetrievedJune 4,2018.