Chang'e 4

Top:Chang'e 4 lander on the surface of the Moon Bottom:Yutu-2rover on lunar surface. | |

| Mission type | Lander,lunar rover |

|---|---|

| Operator | CNSA |

| COSPAR ID | 2018-103A |

| SATCATno. | 43845 |

| Mission duration | Lander: 12 months (planned) 5 years, 6 months, 13 days(in progress) Rover: 3 months (planned)[1] 5 years, 6 months, 13 days(in progress) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Launch mass | Total: 3,780 kg Lander: 3,640 kg[2] Rover: 140 kg[2] |

| Landing mass | Total: ~1,200 kg; rover: 140 kg |

| Dimensions | Rover: 1.5 × 1.0 × 1.0 m[3] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 7 December 2018, 18:23UTC[4] |

| Rocket | Long March 3B[5] |

| Launch site | Xichang Satellite Launch Center,LA-2 |

| Lunarlander | |

| Landing date | 3 January 2019, 02:26 UTC[6] |

| Landing site | Spatio Tianhe[7]withinVon Kármán crater[8]in theSouth Pole-Aitken Basin[9] 45°26′38″S177°35′56″E/ 45.444°S 177.599°E |

| Lunarrover | |

| Landing date | 3 January 2019, 02:26 UTC[10] |

| Landing site | Spatio Tianhe[7]withinVon Kármán crater[8]in theSouth Pole-Aitken Basin[9] |

| Distance driven | 1.596 km (0.992 mi) as of 4 May 2024[update][11] |

Chang'e probes | |

Chang'e 4(/tʃɑːŋˈə/;Chinese:Thường Nga số 4;pinyin:Cháng'é Sìhào;lit.'Chang'eNo. 4') is a robotic spacecraft mission in theChinese Lunar Exploration Programof theCNSA.China achieved humanity's firstsoft landingon thefar side of the Moonwith its touchdown on 3 January 2019.[12][13]

Acommunication relay satellite,Queqiao,was first launched to ahalo orbitnear the Earth–MoonL2pointin May 2018. The roboticlanderandYutu-2(Chinese:Thỏ ngọc số 2;pinyin:Yùtù Èrhào;lit.'Jade RabbitNo. 2')rover[14]were launched on 7 December 2018 and entered lunar orbit on 12 December 2018, before landing on the Moon's far side. On 15 January it was announced that seeds had sprouted in the lunar lander's biological experiment, the first plants to sprout on the Moon. The mission is the follow-up toChang'e 3,the first Chinese landing on the Moon.

The spacecraft was originally built as a backup for Chang'e 3 and became available after Chang'e 3 landed successfully in 2013. The configuration of Chang'e 4 was adjusted to meet new scientific and performance objectives.[15]Like its predecessors, the mission is named afterChang'e,the ChineseMoon goddess.

In November 2019, Chang'e 4 mission team was awarded Gold Medal by theRoyal Aeronautical Society.[16]In October 2020, the mission was awarded theWorld Space Awardby theInternational Astronautical Federation.[17]Both were the first time for any Chinese mission to receive such awards.

Overview[edit]

TheChinese Lunar Exploration Programis designed to be conducted in four[18]phases of incremental technological advancement: The first is simply reaching lunar orbit, a task completed by Chang'e 1 in 2007 andChang'e 2in 2010. The second is landing and roving on the Moon, asChang'e 3did in 2013 and Chang'e 4 did in 2019. The third is collecting lunar samples from the near-side and sending them to Earth, a taskChang'e 5completed in 2020, andChang'e 6that completed in 2024. The fourth phase consists of development of a robotic research station near the Moon's south pole.[18][19][20]

The program aims to facilitate a crewed lunar landing in the 2030s and possibly the building of an outpost near the south pole.[21][22]The Chinese Lunar Exploration Program has started to incorporate private investment from individuals and enterprises for the first time, a move aimed at accelerating aerospace innovation, cutting production costs, and promoting military–civilian relationships.[23]

This mission will attempt to determine the age and composition of an unexplored region of the Moon, as well as develop technologies required for the later stages of the program.[24]

The landing craft touched down at 02:26 UTC on 3 January 2019, becoming the first spacecraft to land on the far side of the Moon.Yutu-2rover was deployed about 12 hours after the landing.

Launch[edit]

The Chang'e 4 mission was first scheduled for launch in 2015 as part of the second phase of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program.[25][26]But the adjusted objectives and design of the mission imposed delays, and finally launched on 7 December 2018, 18:23UTC.[4][27]

Selenocentric phase[edit]

The spacecraft entered lunar orbit on 12 December 2018, 08:45 UTC.[28]The orbit'sperilunewas lowered to 15 km (9.3 mi) on 30 December 2018, 00:55 UTC.[29]

Landing took place on 3 January 2019 at 02:26 UTC,[13]shortly after lunar sunrise over theVon Kármán craterin the largeSouth Pole-Aitken basin.[30]

Objectives[edit]

An ancient collision event on the Moon left behind a very large crater, called theAitken Basin,that is now about 13 km (8.1 mi) deep, and it is thought that the massive impactor likely exposed the deep lunarcrust,and probably themantlematerials. If Chang'e 4 can find and study some of this material, it would get an unprecedented view into the Moon's internal structure and origins.[1]The specific scientific objectives are:[31]

- Measure the chemical compositions oflunar rocksandsoils

- Measure lunar surface temperature over the duration of the mission.

- Carry out low-frequency radio astronomical observation and research using aradio telescope

- Study ofcosmic rays

- Observe thesolar corona,investigate its radiation characteristics and mechanism, and explore the evolution and transport ofcoronal mass ejections(CME) between the Sun and Earth.

Components[edit]

Queqiaorelay satellite[edit]

Direct communication with Earth is impossible on thefar side of the Moon,since transmissions are blocked by the Moon. Communications must go through acommunications relay satellite,which is placed at a location that has a clear view of both the landing site and the Earth. As part of the Lunar Exploration Program, theChina National Space Administration(CNSA) launched theQueqiao(Chinese:Cầu Hỉ Thước;pinyin:Quèqiáo;lit.'Magpie Bridge') relay satellite on 20 May 2018 to ahalo orbitaround the Earth–MoonL2point.[32][33][34]The relay satellite is based on theChang'e 2design,[35]has a mass of 425 kg (937 lb), and it uses a 4.2 m (14 ft) antenna to receiveX bandsignals from the lander and rover, and relay them to Earth control on theS band.[36]

The spacecraft took 24 days to reach L2,using a lunarswing-byto save fuel.[37]On 14 June 2018,Queqiaofinished its final adjustment burn and entered the L2halo mission orbit, which is about 65,000 kilometres (40,000 mi) from the Moon. This is the first lunar relay satellite at this location.[37]

The nameQueqiao( "Magpie Bridge" ) was inspired by and came from the Chinese taleThe Cowherd and the Weaver Girl.[32]

Long gian gmicrosatellites[edit]

As part of the Chang'e 4 mission, two microsatellites (45 kg or 99 lb each) namedLong gian g-1andLong gian g-2(Chinese:Long Giang;pinyin:Lóng Jiāng;lit.'Dragon River';[38]also known asDiscovering the Sky at Longest Wavelengths PathfinderorDSLWP[39]), were launched along withQueqiaoin May 2018. Both satellites were developed byHarbin Institute of Technology,China.[40]Long gian g-1failed to enter lunar orbit,[37]butLong gian g-2succeeded and operated in lunar orbit until 31 July 2019 when it was deliberately directed to crash onto the Moon.[41]

Long gian g 2's crash site is located at16°41′44″N159°31′01″E/ 16.6956°N 159.5170°EinsideVan Gentcrater, where it made a 4 by 5 metre crater upon impact.[42] These microsatellites were tasked to observe the sky at very low frequencies (1–30megahertz), corresponding towavelengthsof 300 to 10 metres (984 to 33 ft), with the aim of studying energetic phenomena from celestial sources.[34][43][44]Due to the Earth'sionosphere,no observations in this frequency range have been done in Earth orbit,[44]offering potential breakthrough science.[24]

Chang'elander andYutu-2rover[edit]

The Chang'e 4 lander and rover design was modeled after Chang'e-3 and itsYuturover.In fact, Chang'e 4 was built as a backup toChang'e 3,[45]and based on the experience and results from that mission, Chang'e 4 was adapted to the specifics of the new mission.[46]The lander and rover were launched byLong March 3Brocket on 7 December 2018, 18:23 UTC, six months after the launch of theQueqiaorelay satellite.[4]

The total landing mass is 1,200 kg (2,600 lb).[2]Both the stationary lander andYutu-2rover are equipped with aradioisotope heater unit(RHU) in order to heat their subsystems during the long lunar nights,[47]while electrical power is generated bysolar panels.

After landing, the lander extended a ramp to deploy theYutu-2rover (literally: "Jade Rabbit") to the lunar surface.[37]The rover measures 1.5 × 1.0 × 1.0 m (4.9 × 3.3 × 3.3 ft) and has a mass of 140 kg (310 lb).[2][3]Yutu-2rover was manufactured by theChina Academy of Space Technology;it is solar-powered, RHU-heated,[47]and it is propelled by six wheels. The rover's nominal operating time is three months,[1]but after the experience withYuturoverin 2013, the rover design was improved and Chinese engineers are hopeful it will operate for "a few years".[48]On November 21, 2019,Yutu 2broke the lunar longevity record, of 322 Earth days, previously held by the Soviet Union'sLunokhod 1rover (Nov. 17, 1970 to Oct. 4, 1971).[49]

Science payloads[edit]

The communications relay satellite, orbiting microsatellite, lander and rover each carry scientific payloads. The relay satellite is performingradio astronomy,[50]whereas the lander andYutu-2rover will study thegeophysicsof the landing zone.[8][51]The science payloads are, in part, supplied by international partners in Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, and Saudi Arabia.[52]

Relay satellite[edit]

The primary function of theQueqiao relay satellitethat is deployed in ahalo orbitaround theEarth–Moon L2pointis to provide continuous relay communications between Earth and the lander on the far side of the Moon.[34][50]

TheQueqiaolaunched on 21 May 2018. It used a lunar swing-by transfer orbit to reach the Moon. After the first trajectory correction maneuvers (TCMs), the spacecraft is in place. On 25 May,Queqiaoapproached the vicinity of the L2.After several small adjustments,Queqiaoarrived at L2halo orbiton 14 June.[53][54]

Additionally, this satellite hosts theNetherlands–China Low-Frequency Explorer(NCLE), an instrument performingastrophysical studiesin the unexplored radio regime of 80 kilohertz to 80 megahertz.[55][56]It was developed by theRadboud Universityin Netherlands and theChinese Academy of Sciences.The NCLE on the orbiter and the LFS on the lander work in synergy performing low-frequency (0.1–80 MHz) radio astronomical observations.[43]

Lunar lander[edit]

The lander and rover carry scientific payloads to study the geophysics of the landing zone, with alife scienceand modest chemical analysis capability.[8][51][43]The lander is equipped with the following payloads:

- Landing Camera (LCAM), mounted on the bottom of the spacecraft, the camera began to produce a video stream at the height of 12 km (7.5 mi) above the lunar surface.

- Terrain Camera (TCAM), mounted on top of the lander and able to rotate 360°, is being used to image the lunar surface and the rover in high definition.

- Low Frequency Spectrometer (LFS)[43]to researchsolar radio burstsat frequencies between 0.1 and 40 MHz and to study the lunar ionosphere.

- Lunar Lander Neutrons and Dosimetry (LND), a (neutron) dosimeter developed byKiel Universityin Germany.[57]It is gathering information about radiation dosimetry for future human exploration of the Moon, and will contribute tosolar windstudies.[58][59]It has shown that the radiation dose on the surface of the Moon is 2 to 3 times higher than what astronauts experience in the ISS.[60][61]

- Lunar Micro Ecosystem,[62]is a 3 kg (6.6 lb) sealedbiospherecylinder 18 cm (7.1 in) long and 16 cm (6.3 in) in diameter with seeds and insect eggs to test whether plants and insects could hatch and grow together in synergy.[55]The experiment includes six types of organisms:[63][64]cottonseed,potato,rapeseed,Arabidopsis thaliana(a flowering plant), as well as yeast andfruit fly[65]eggs. Environmental systems keep the container hospitable and Earth-like, except for the low lunar gravity and radiation.[66]If the fly eggs hatch, the larvae would produce carbon dioxide, while the germinated plants would releaseoxygenthroughphotosynthesis.It was hoped that together, the plants and fruit flies could establish a simple synergy within the container.[citation needed]Yeast would play a role in regulating carbon dioxide and oxygen, as well as decomposing processed waste from the flies and the dead plants to create an additional food source for the insects.[63]The biological experiment was designed by 28 Chinese universities.[67]Research in suchclosed ecological systemsinformsastrobiologyand the development of biologicallife support systemsfor long duration missions inspace stationsorspace habitatsfor eventualspace farming.[68][69][70]

- Result:Within a few hours after landing on 3 January 2019, the biosphere's temperature was adjusted to 24°C and the seeds were watered. On 15 January 2019, it was reported that cottonseed, rapeseed and potato seeds had sprouted, but images of only cottonseed were released.[63]However, on 16 January, it was reported that the experiment was terminated due to an external temperature drop to −52 °C (−62 °F) as the lunar night set in, and a failure to warm the biosphere close to 24°C.[71]The experiment was terminated after nine days instead of the planned 100 days, but valuable information was obtained.[71][72]

Lunar rover[edit]

- Panoramic Camera (PCAM), is installed on the rover's mast and can rotate 360°. It has a spectral range of 420 nm–700 nm and it acquires 3D images by binocular stereovision.[43]

- Lunar penetrating radar (LPR), is aground penetrating radarwith a probing depth of approximately 30 m with 30 cm vertical resolution, and more than 100 m with 10 m vertical resolution.[43]

- Visible and Near-Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (VNIS), forimaging spectroscopythat can then be used for identification of surface materials and atmospheric trace gases. The spectral range covers visible to near-infrared wavelengths (450 nm - 950 nm).

- Advanced Small Analyzer for Neutrals (ASAN), is anenergetic neutral atomanalyzer provided by theSwedish Institute of Space Physics(IRF). It will reveal how solar wind interacts with the lunar surface, which may help determine the process behind the formation oflunar water.[57]

Cost[edit]

According to the deputy project director, who would not quote an exact amount, "The cost (of the entire mission) is close to building one kilometer ofsubway."[73]The cost-per-kilometre ofsubway in Chinavaries from 500 million yuan (about US$72 million) to 1.2 billion yuan (about US$172 million), based on the difficulty of construction.[73]

Landing site[edit]

The landing site is within a crater calledVon Kármán[8](180 km (110 mi) diameter) in theSouth Pole-Aitken Basinon thefar side of the Moonthat was still unexplored by landers.[9][74]The site has symbolic as well as scientific value.Theodore von Kármánwas the PhD advisor ofQian Xuesen,the founder of theChinese space program.[75]

The landing craft touched down at 02:26 UTC on 3 January 2019, becoming the first spacecraft to land on the far side of the Moon.[76]

TheYutu-2rover was deployed about 12 hours after the landing.[77]

Theselenographic coordinatesof the landing site are 177.5991°E, 45.4446°S, at an elevation of -5935 m.[78][79]The landing site was later (February 2019) namedStatio Tianhe.[7]Four other lunar features were also named during this mission: a mountain (Mons Tai) and three craters (Zhinyu,Hegu,andTianjin).[80]

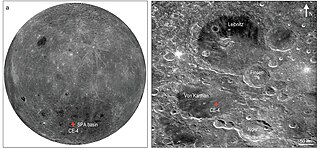

-

A view of landing site, marked by two small arrows, taken by theLunar Reconnaissance Orbiteron 30 January 2019[81]

-

Chang'e 4 – Lander (left arrow) and Rover (right arrow) on the Moon surface (NASA photo, 8 February 2019).[82]

-

Chang'e 4 lander (center) and rover (west-northwest of lander) 6 months after landing.

Operations and results[edit]

A few days after landing,Yutu-2went into hibernation for its first lunar night and it resumed activities on 29 January 2019 with all instruments operating nominally. During its first full lunar day, the rover travelled 120 m (390 ft), and on 11 February 2019 it powered down for its second lunar night.[83][84]In May 2019, it was reported that Chang'e 4 has identified what appear to be mantle rocks on the surface, its primary objective.[85][86][87]

In January 2020, China released a large amount of data and high-resolution images from the mission lander and rover.[88]In February 2020, Chinese astronomers reported, for the first time, a high-resolution image of alunar ejecta sequence,and, as well, direct analysis of its internal architecture. These were based on observations made by theLunar Penetrating Radar(LPR) on board theYutu-2rover while studying thefar side of the Moon.[89][90]

International collaboration[edit]

Chang'e 4 marks the first major United States-China collaboration in space exploration since the2011 Congressional ban.Scientists from both countries had regular contact prior to the landing.[91]This included talks about observing plumes and particles lofted from the lunar surface by the probe's rocket exhaust during the landing to compare the results with theoretical predictions, but NASA'sLunar Reconnaissance Orbiter(LRO) was not in the right position for this during the landing.[92]The Americans informed Chinese scientists about its satellites in orbit around the Moon, while the Chinese shared with American scientists the longitude, latitude, and timing of Chang'e 4's landing.[93]

China has agreed to a request from NASA to use the Chang'e 4 probe and Queqiao relay satellite in future American Moon missions.[94]

International reactions[edit]

NASA AdministratorJim Bridenstinecongratulated China and hailed the success of the mission as "an impressive accomplishment".[95]

Martin Wieser of theSwedish Institute of Space Physicsand principal investigator on one of the instruments onboard Chang'e, said: "We know the far side from orbital images and satellites, but we don't know it from the surface. It's uncharted territory and that makes it very exciting."[96]

Gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

- Animals in space

- Plants in space

- Closed ecological system

- Exploration of the Moon

- List of missions to the Moon

- Luna 3,the first spacecraft to image the lunar far side

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

References[edit]

- ^abcChina says it will launch 2 robots to the far side of the Moon in December on an unprecedented lunar exploration missionArchived9 December 2018 at theWayback Machine.Dave Mosher,Business Insider16 August 2018

- ^abcdChang'e 3, 4 (CE 3, 4)Archived20 March 2018 at theWayback Machine.Gunter Dirk Krebs,Gunter's Space Page.

- ^abThis is the rover China will send to the 'dark side' of the MoonArchived31 August 2018 at theWayback MachineSteven Jiang, CNN News 16 August 2018

- ^abc"Thăm người làm công tháng trình Thường Nga số 4 dò xét khí thành công phóng ra mở ra nhân loại lần đầu mặt trăng mặt trái hạ cánh nhẹ nhàng dò xét chi lữ"(in Chinese (China)). China National Space Administration. Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2018.Retrieved8 December2018.

- ^"Launch Schedule 2018".Spaceflight Now.18 September 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2016.Retrieved18 September2018.

- ^Barbosa, Rui (3 January 2019)."China lands Chang'e-4 mission on the far side of the Moon".NASASpaceFlight.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^abc"Chang'e-4 landing site named" Statio Tianhe "".Xinhua. 15 February 2019.Retrieved29 June2024.

- ^abcdeChina's Journey to the Lunar Far Side: A Missed Opportunity?Archived9 December 2018 at theWayback MachinePaul D. Spudis,Air & Space Smithsonian.14 June 2017.

- ^abcYe, Pei gian; Sun, Zezhou; Zhang, He; Li, Fei (2017). "An overview of the mission and technical characteristics of Change'4 Lunar Probe".Science China Technological Sciences.60(5): 658.Bibcode:2017ScChE..60..658Y.doi:10.1007/s11431-016-9034-6.S2CID126303995.

- ^Barbosa, Rui (3 January 2019)."China lands Chang'e-4 mission on the far side of the Moon".NASASpaceFlight.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^"Trung Quốc thăm người làm công tháng trình đã được duyệt 20 năm nhìn lại" Thường Nga "Bôn nguyệt chi lữ"(in Simplified Chinese). CCTV tin tức. 4 May 2024.Retrieved5 May2024.

- ^Lyons, Kate."Chang'e 4 landing: China probe makes historic touchdown on far side of the moon".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^ab"China successfully lands Chang'e-4 on far side of Moon".Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^Mosherand, Dave; Gal, Shayanne (3 January 2019)."This map shows exactly where China landed its Chang'e-4 spacecraft on the far side of the moon".Business Insider.Archived fromthe originalon 4 January 2019.

- ^Notably, the rover was modified "to meet the demands of the far-side terrain, but also to avoid the fate of the robot's predecessor, which became immobilized after driving only 360 feet (110 meters)"Pearlman, Robert Z. (12 December 2018)."China's Chang'e 4 Moon Lander and Rover to Touch Down As Toys".Future US, Inc.Archivedfrom the original on 13 August 2023.Retrieved15 November2019.

- ^"Plane Speaking with Dr Wu Weiren".Aero Society.10 December 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 15 March 2023.Retrieved6 December2022.

- ^"IAF WORLD SPACE AWARD – THE CHANG'E 4 MISSION".International Astronautical Federation.Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2022.Retrieved14 August2021.

- ^abChang'e 4 press conferenceArchived15 December 2020 at theWayback Machine.CNSA, broadcast on 14 January 2019.

- ^China's Planning for Deep Space Exploration and Lunar Exploration before 2030Archived3 March 2021 at theWayback Machine.(PDF) XU Lin, ZOU Yongliao, JIA Yingzhuo.Space Sci., 2018, 38(5): 591-592.doi:10.11728/cjss2018.05.591

- ^A Tentative Plan of China to Establish a Lunar Research Station in the Next Ten YearsArchived15 December 2020 at theWayback Machine.Zou, Yongliao; Xu, Lin; Jia, Yingzhuo. 42nd COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 14–22 July 2018, in Pasadena, California, USA, Abstract id. B3.1-34-18.

- ^China lays out its ambitions to colonize the moon and build a "lunar palace"Archived29 November 2018 at theWayback Machine.Echo Huang,Quartz.26 April 2018.

- ^China's moon mission to boldly go a step furtherArchived31 December 2017 at theWayback Machine.Stuart Clark,The Guardian31 December 2017.

- ^"China Outlines New Rockets, Space Station and Moon Plans".Space. 17 March 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 1 July 2016.Retrieved27 March2015.

- ^abChina's Moon Missions Are Anything But PointlessArchived10 April 2019 at theWayback Machine.Paul D. Spudis,Air & Space Smithsonian.3 January 2017.

- ^"Ouyang Ziyuan portrayed Chang E project follow-up blueprint".Science Times. 9 December 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 3 February 2012.Retrieved25 June2012.

- ^Witze, Alexandra (19 March 2013)."China's Moon rover awake but immobile".Nature.doi:10.1038/nature.2014.14906.S2CID131617225.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2014.Retrieved25 March2014.

- ^China launches historic mission to land on far side of the moonArchived7 December 2018 at theWayback MachineStephen Clark,Spaceflight Now.7 December 2018.

- ^"China's Chang'e-4 probe decelerates near moon".Xinhua.12 December 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 12 December 2018.Retrieved12 December2018.

- ^"China's Chang'e-4 probe changes orbit to prepare for moon-landing".XinhuaNet.30 December 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 1 January 2019.Retrieved31 December2018.

- ^Jones, Andrew (31 December 2018)."How the Chang'e-4 spacecraft will land on the far side of the Moon".GBTIMES.Archived fromthe originalon 2 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^To the Far Side of the Moon: China's Lunar Science GoalsArchived10 March 2018 at theWayback Machine.Leonard David,Space.9 June 2016.

- ^abWall, Mike (18 May 2018)."China Launching Relay Satellite Toward Moon's Far Side Sunday".Space.Archived fromthe originalon 18 May 2018.

- ^Emily Lakdawalla (14 January 2016)."Updates on China's lunar missions".The Planetary Society.Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2016.Retrieved24 April2016.

- ^abcJones, Andrew (24 April 2018)."Chang'e-4 lunar far side satellite named 'magpie bridge' from folklore tale of lovers crossing the Milky Way".GBTimes.Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2018.Retrieved28 April2018.

- ^Future Chinese Lunar Missions: Chang'e 4 - Farside Lander and RoverArchived4 January 2019 at theWayback Machine.David R. Williams, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 7 December 2018.

- ^Chang'e 4 relay satellite, Queqiao: A bridge between Earth and the mysterious lunar farsideArchived21 May 2018 at theWayback Machine.Xu, Luyan,The Planetary Society.19 May 2018. Retrieved on 20 May 2018

- ^abcdXu, Luyuan (15 June 2018)."How China's lunar relay satellite arrived in its final orbit".The Planetary Society.Archived fromthe originalon 17 October 2018.

- ^Radio Experiment Launches With China's Moon OrbiterArchived26 January 2020 at theWayback Machine.David Dickinson,Sky & Telescope.21 May 2018.

- ^China Moon Mission: Lunar Microsatellite Problem?Archived17 April 2019 at theWayback Machine.Leonard David,Inside Outer Space.27 May 2018.

- ^Andrew Jones (5 August 2019)."Lunar Orbiter Long gian g-2 Smashes into Moon".Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2023.Retrieved3 March2023.

- ^@planet4589 (31 July 2019)."The Chinese Long gian g-2 (DSLWP-B) lunar orbiting spacecraft completed its mission on Jul 31 at about 1420 UTC, in a planned i[m]pact on the lunar surface"(Tweet).Retrieved1 August2019– viaTwitter.

- ^"Long gian g-2 Impact Site Found! | Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera".lroc.sese.asu.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 14 November 2019.Retrieved14 November2019.

- ^abcdefThe scientific objectives and payloads of Chang'E−4 missionArchived19 August 2019 at theWayback Machine.(PDF) Yingzhuo Jia, Yongliao Zou, Jinsong Ping, Changbin Xue, Jun Yan, Yuanming Ning.Planetary and Space Science.21 February 2018.doi:10.1016/j.pss.2018.02.011

- ^abJones, Andrew (1 March 2018)."Chang'e-4 lunar far side mission to carry microsatellites for pioneering astronomy".GB Times.Archivedfrom the original on 10 March 2018.Retrieved1 August2019.

- ^Wang, Qiong; Liu, Jizhong (2016). "A Chang'e-4 mission concept and vision of future Chinese lunar exploration activities".Acta Astronautica.127:678–683.Bibcode:2016AcAau.127..678W.doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2016.06.024.

- ^Pioneering Chang'e-4 lunar far side landing mission to launch in December.Andrew Jones,Space News.15 August 2018.

- ^abChina Shoots for the Moon's Far SideArchived4 January 2019 at theWayback Machine.(PDF) IEEE.org. 2018.

- ^China's Chang'e 4 spacecraft to try historic landing on far side of Moon 'between January 1 and 3'Archived2 January 2019 at theWayback Machine.South China Morning Post.31 December 2018.

- ^China's Farside Moon Rover Breaks Lunar Longevity Record.Archived24 December 2020 at theWayback MachineLeonard David,Space.12 December 2019.

- ^abChang'e 4 RelayArchived1 January 2018 at theWayback Machine.Gunter Drunk Krebs,Gunter's Space Page.

- ^abPlans for China's farside Chang'e 4 lander science mission taking shapeArchived23 June 2016 at theWayback Machine.Emily Lakdawalla,The Planetary Society,22 June 2016.

- ^Andrew Jones (11 January 2018)."Testing on China's Chang'e-4 lunar far side lander and rover steps up in preparation for launch".GBTimes.Archived fromthe originalon 12 January 2018.Retrieved12 January2018.

- ^Jones, Andrew (21 May 2018)."China launches Queqiao relay satellite to support Chang'e 4 lunar far side landing mission".GBTimes.Archived fromthe originalon 22 May 2018.Retrieved22 May2018.

- ^Luyuan Xu (15 June 2018)."How China's lunar relay satellite arrived in its final orbit".planetary.org.Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2019.Retrieved17 January2020.

- ^abDavid, Leonard."Comsat Launch Bolsters China's Dreams for Landing on the Moon's Far Side".Scientific American.Archived fromthe originalon 29 November 2018.

- ^"Netherlands–China Low-Frequency Explorer (NCLE)".ASTRON. Archived fromthe originalon 10 April 2018.Retrieved10 April2018.

- ^abAndrew Jones (16 May 2016)."Sweden joins China's historic mission to land on the far side of the Moon in 2018".GBTimes.Archived fromthe originalon 6 October 2018.Retrieved12 January2018.

- ^Wimmer-Schweingruber, Robert f. (18 August 2020)."The Lunar Lander Neutron and Dosimetry (LND) Experiment on Chang'E 4".Space Science Reviews.216(6): 104.arXiv:2001.11028.Bibcode:2020SSRv..216..104W.doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00725-3.S2CID73641057.

- ^The Lunar Lander Neutron & Dosimetry (LND) Experiment on Chang'E4Archived3 January 2019 at theWayback Machine.(PDF) Robert F. Wimmer-Schweingruber, S. Zhang, C. E. Hellweg, Jia Yu, etal. Institut für Experimentelle und Angewandte Physik. Germany.

- ^Mann, Adam (25 September 2020)."Moon safe for long-term human exploration, first surface radiation measurements show".Science.doi:10.1126/science.abe9386.S2CID224903056.

- ^Zhang, Shenyi (25 September 2020)."First measurements of the radiation dose on the lunar surface".Science Advances.6(39).Bibcode:2020SciA....6.1334Z.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz1334.PMC7518862.PMID32978156.

- ^Geological Characteristics of Chang'e-4 Landing SiteArchived31 May 2018 at theWayback Machine.(PDF) Jun Huang, Zhiyong Xiao, Jessica Flahaut, Mélissa Martinot, Xiao Xiao. 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083).

- ^abcZheng, William (15 January 2019)."Chinese lunar lander's cotton seeds spring to life on far side of the moon".South China Morning Post.Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2019.Retrieved15 January2019.

- ^Moon sees first cotton-seed sprout.Xinhua News.15 January 2019.

- ^"Change-4 Probe lands on the moon with" mysterious passenger "of CQU".Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2019.Retrieved17 January2019.

- ^China Is About to Land Living Eggs on the Far Side of the MoonArchived2 January 2019 at theWayback Machine.Yasmin Tayag,Inverse.2 January 2019.

- ^Rincon, Paul (2 January 2019)."Chang'e-4: China mission primed for landing on Moon's far side".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^Space 2018: China mission will create miniature ecosystem on MoonArchived4 April 2018 at theWayback Machine.Karen Graham,Digital Journal.6 January 2018.

- ^Forget the stratospheric chicken sandwich, China is sending potato seeds and silkworms to the MoonArchived17 September 2017 at theWayback Machine.Andrew Jones,GB Times.14 June 2017.

- ^China Focus: Flowers on the Moon? China's Chang'e-4 to launch lunar springArchived27 December 2018 at theWayback Machine.Xinhua(in English). 4 April 2018.

- ^abLunar nighttime brings end to Chang'e-4 biosphere experiment and cotton sproutsArchived29 July 2019 at theWayback Machine.Andrew Jones,GB Times.16 January 2019.

- ^China's first plant to grow on the moon is already deadArchived17 January 2019 at theWayback Machine.Yong Xiong and Ben Westcott,CNN News.17 January 2019.

- ^abECNSArchived19 March 2023 at theWayback Machine2019-07-31

- ^"China Plans First Ever Landing on the Lunar Far Side".Space Daily. 22 May 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 26 May 2015.Retrieved26 May2015.

- ^"Hsue-Shen Tsien".Mathematics Genealogy Project.Archivedfrom the original on 9 December 2018.Retrieved7 December2018.

- ^"Chang'e 4: China probe lands on far side of the moon".The Guardian.3 January 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^Chang'e-4: Chinese rover now exploring MoonArchived4 January 2019 at theWayback MachinePaul RinconBBC News4 January 2019

- ^Mack, Eric."China's Chang'e moon probe: We finally know exactly where the spacecraft landed".CNET.Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2019.Retrieved25 September2019.

- ^Liu, Jianjun; Ren, Xin; Yan, Wei; Li, Chunlai; Zhang, He; Jia, Yang; Zeng, Xingguo; Chen, Wangli; Gao, Xingye; Liu, Dawei; Tan, Xu (24 September 2019)."Descent trajectory reconstruction and landing site positioning of Chang'e 4 on the lunar farside".Nature Communications.10(1): 4229.Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.4229L.doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12278-3.ISSN2041-1723.PMC6760200.PMID31551413.

- ^Bartels, Meghan (15 February 2019)."China's Landing Site on the Far Side of the Moon Now Has a Name".SPACE.Archivedfrom the original on 15 February 2019.Retrieved17 May2020.

- ^Robinson, Mark (6 February 2019)."First Look: Chang'e 4".Arizona State University.Archivedfrom the original on 30 March 2023.Retrieved8 February2019.

- ^NASA (8 February 2019)."Chang'e 4 Rover comes into view".EurekAlert!.Archivedfrom the original on 7 June 2021.Retrieved9 February2019.

- ^Jones, Andrew (11 February 2019)."Chang'e-4 powers down for second lunar night".SpaceNews.Retrieved1 August2019.

- ^Caraiman, Vadim Ioan (11 February 2019)."Chinese Lunar Probe, Chang'e-4, Goes Standby Mode For The Second Lunar Night on The Dark Side of The Moon".Great Lakes Ledger.Archivedfrom the original on 16 February 2019.Retrieved1 August2019.

- ^Ouyang, Ziyuan; Zhang, Hongbo; Su, Yan; Wen, Weibin; Shu, Rong; Chen, Wangli; Zhang, Xiaoxia; Tan, Xu; Xu, Rui (May 2019). "Chang'E-4 initial spectroscopic identification of lunar far-side mantle-derived materials".Nature.569(7756): 378–382.Bibcode:2019Natur.569..378L.doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1189-0.ISSN1476-4687.PMID31092939.S2CID205571018.

- ^Strickland, Ashley (15 May 2019)."Chinese mission uncovers secrets on the far side of the moon".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 16 May 2019.Retrieved16 May2019.

- ^Rincon, Paul (15 May 2019)."Chang'e-4: Chinese rover 'confirms' Moon crater theory".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2019.Retrieved1 August2019.

- ^Jones, Andrew (22 January 2020)."China releases huge batch of amazing Chang'e-4 images from moon's far side".SPACE.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2020.Retrieved22 January2020.

- ^Chang, Kenneth (26 February 2020)."China's Rover Finds Layers of Surprise Under Moon's Far Side - The Chang'e-4 mission, the first to land on the lunar far side, is demonstrating the promise and peril of using ground-penetrating radar in planetary science".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 26 February 2020.Retrieved27 February2020.

- ^Li, Chunlai; et al. (26 February 2020)."The Moon's farside shallow subsurface structure unveiled by Chang'E-4 Lunar Penetrating Radar".Science Advances.6(9): eaay6898.Bibcode:2020SciA....6.6898L.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay6898.PMC7043921.PMID32133404.

- ^Jones, Andrew (15 January 2019)."Chang'e-4 spacecraft enter lunar nighttime, China planning future missions, cooperation".SpaceNews.Retrieved14 February2019.

- ^David, Leonard (7 February 2019)."Farside Politics: The West Eyes Moon Cooperation with China".Scientific American.Archivedfrom the original on 13 February 2019.Retrieved14 February2019.

- ^Li, Zheng (13 February 2019)."Space a new realm for Sino-US cooperation".China Daily.Archivedfrom the original on 14 February 2019.Retrieved14 February2019.

- ^Needham, Kirsty (19 January 2019)."Red moon rising: China's mission to the far side".The Sydney Morning Herald.Archivedfrom the original on 6 March 2019.Retrieved2 March2019.

- ^Lyons, Kate."Chang'e 4 landing: China probe makes historic touchdown on far side of the moon".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^Lyons, Kate."Chang'e 4 landing: China probe makes historic touchdown on far side of the moon".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2019.Retrieved3 January2019.

![A view of landing site, marked by two small arrows, taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter on 30 January 2019[81]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/LRO_Chang%27e_4%2C_first_look.png/280px-LRO_Chang%27e_4%2C_first_look.png)

![Chang'e 4 – Lander (left arrow) and Rover (right arrow) on the Moon surface (NASA photo, 8 February 2019).[82]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3c/NASA-Chang%27e4-Lander%26Rover-OnMoonSurface-20190208.jpg/280px-NASA-Chang%27e4-Lander%26Rover-OnMoonSurface-20190208.jpg)