Ludovic Antal

Ludovic Antal | |

|---|---|

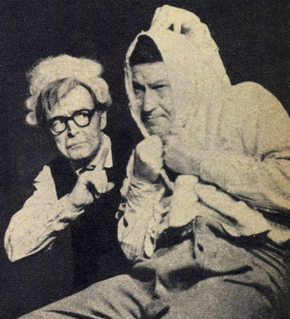

Antal in 1968 | |

| Born | 18 February 1924 |

| Died | October 1970(aged 46) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1945–1970 |

| Spouse |

Reli Roman (divorced) |

| Awards | Meritul Cultural |

Ludovic Antal(18 February 1924 – October 1970) was a Romanian actor, primarily noted for his voice acting and his activity as a cultural promoter. Born toCsángóparents inWestern Moldavia,he was initially destined for a career as a priest in theRoman Catholic Church,but left to study acting in the late 1940s, graduating from the OMEC conservatoire. After making his stage debut with a workers' theater inBucharest,Antal attended theNational Theatrical Institutein Bucharest. His break and artistic recognition occurred during a time when Romania was under acommunist regime,and he took on a number of roles in ideological plays, as well as in the 1951 propaganda filmIn Our Village.Antal still received poor reviews for his early stage work and voice acting, and was also regarded as politically suspect by the authorities, which accounted for his relative marginalization. He remained under contract with various troupes, and was primarily associated withNottara Theater,but was generally not cast, or only offered minor parts.

From the early 1960s, theRomanian Radio Companyconsecrated Antal as one of its main reciters of poems byMihai Eminescu,a work which made him nationally famous. An occasional presenter forRomania's state television,he toured the country promoting poetry, covering the entirety ofnational literature—from the early staples ofRomanian folklore,through the works of Eminescu andOctavian Goga,and down to modern pieces byTudor Arghezi,Ion Minulescu,and various others; his activity also covered renditions of prose byTitu Maiorescu,as well as samples of Arghezi'schildren's literature.Committed toRomanian nationalism,in the mid-to-late 1960s he also provided readings from Eminescu'sDoina,testing the limits ofcommunist censorship.His second break in theater came in mid-1969, when he starred in Nottara's critically acclaimed adaptation ofGarabet Ibrăileanu'sAdela.In early 1970, he was diagnosed withlung cancer;despite undergoing an emergency procedure, he died in October of that year.

Biography

[edit]Origins and rise to fame

[edit]Antal was born on 18 February 1924[1][2]in Miclăușeni village (part ofButeacommune,Iași County). His parents were Csángós (Hungarian Romanians).[3][4]Though it remains unknown if he himself ever learnedHungarian,[4]he was baptized a Roman Catholic, like the rest of his community.[5]Antal was originally ordained a priest of the Catholic Church, but left this career to pursue acting.[4]His official biography lists him as a graduate of the Drama and Film Institute in Bucharest (now Caragiale National University, UNATC),[1]but fellow actor Paul Sava reported in 1973 that they both graduated from OMEC, the "Workers' Conservatoire", in or around 1945.[6]Antal himself recalled that his debut play wasUncle Vanya,taken up by a students' troupe in 1947–1948.[7]By August 1947, he and Sava were employees of the Frimu Workers' Theater onUranus Hill,appearing together in a production ofCharles Méré'sLa Captive.[8]Antal enlisted at the UNATC around 1950, and studied there underAura Buzescu,a "great dame of the Romanian stage".[7]

Antal's friend, the writerBen Corlaciu,rated him as a man of "true and refined culture", well above that displayed by other actors;[9]another companion, the poetGeo Dumitrescu,reportedly called Antal a "lover of the muses" (amant al muzelor).[7]It was Buzescu who discovered his abilities in reciting poetry, and she encouraged him to perform at the Eminescu Centennial in 1950, where he took accolades for his variant of "Out of All the Masts".[7]According to his colleagueDionisie Vitcu,Antal excelled in the classical repertoire, and was an outstanding reciter of poetry: "he fit so well into an author's personality, that one would have been tempted over and over again to assume that it was he who had authored the verse in question."[10]Poet Petre Pascu was similarly impressed by Antal's "golden voice" and "outstandingly beautiful physique"; he quotes the senior art historianPetru Comarnescu,who described Antal as being only slightly inferior to the consecrated reciterGeorge Vraca.[11]

The Radio Company's homage to Eminescu in March 1961 had Antal and Vraca among the voice actors; the event became an annual tradition, into the 1980s.[12]Overall, he was billed as "the greatest Eminescu reciter".[4][13]He himself once described Eminescu's lyrical work as the Romanians' version of theLord's Prayer.[7]As noted by Corlaciu, Antal only picked up solo performances "for almost a quarter of a century" because of "zealots" (habotnici) who had tried to prevent him from acting in regular plays; the scope of his activity went from the ancestral balladMiorițato fragments from not-yet-published junior poets of the 1960s.[9]WriterIon Pasasserted that "the poets (and I do mean: all the poets) have found in him an astute reader, a faithful translator, and a popularizer. Perhaps his one true vocation was in allowing poetry to be known and loved by an ever-growing circle of the public".[14]He notes that the main object of Antal's literary passion wasTudor Arghezi,with at least one Arghezi poem featured per recital.[15]

Antal was for long associated withNottara Theaterof Bucharest, where he made his first appearance as a professional actor—he was Teterev inThe Philistines,byMaxim Gorky.[7]He was formally employed by several institutions, initially including theNational Theater Bucharest,Giulești Workers' Theatre,and the Film Actors' Studio.[1]His artistic peak coincided with theera of Romanian communism,resulting in more controversial aspects of his career: as noted by Vitcu, Antal agreed to appear in plays honoringCommunist-Partyactivists, and in this "paid his tribute, like all actors did."[10]He was assigned a leading role inJean Georgescu's 1951 filmIn Our Village,which celebratedcollective farming practices,[16]though, according to critic Călin Căliman, it was objectively superior to other productions of day.[17]Antal's official obituary recognized him as having taken on "roles of responsibility from the national and world repertoire", and noted him as a recipient ofMeritul Culturalmedal.[1]He was frequently employed as a narrator throughout that decade, but, according to columnist Mihai Iacob, his contributions were markedly "theatrical" —until he corrected himself for aNina Behar's documentary on painterȘtefan Luchian(1958).[18]He appeared at Nottara in a March 1957 production ofEmmanuel Roblès'Montserrat,but, according to reviewer Radu Popescu, was "superficial and declamatory", "without vocal means".[19]

Around 1954, Antal was flouting communist expectations by joining an informal "literary circle" of social drinkers, which included sculptor Ion Vlad, poetsTiberiu IliescuandDimitrie Stelaru,journalistEmil Serghie,philosopherSorin Pavel,and lawyer-diaristPetre Pandrea.[20]He remained especially close to Stelaru, and reportedly made efforts to promote his poetic works into the mid-1960s.[2]WriterGheorghe Grigurcu,who met Antal as a youth, recalls that his renditions of poetry were sometimes inspired by his being "gently exalted by alcohol".[21]As recalled by writer and period witness Ion Papuc, his habit of drinking before public appearances harmed his chances as a communist propagandist: once made to perform for a rural show celebrating collectivization, the inebriated Antal forgot the "propaganda poetry" he was supposed to recite, and improvised by performingGeorge Coșbuc's "We Demand Land", which featured a celebration of individual property and roused the peasants to rebellion; as a result, "communist activists fled the room in silence, then ran over the fields", and the collectivization project was effectively curbed in that village.[22]

Final years and death

[edit]

Antal also compensated for his political roles by embracingRomanian nationalismwhenever he could, and, Vitcu recalls, was a "thorn in the side" ofofficial censorship.[10]He made a point of memorizing and reciting Eminescu'sDoina,which theSoviet Unionhad tried to suppress. Antal was allegedly the "first one who dared" to quote from it,[13]and in any case the first one to engage in a public rendition.[23]According to Antal's brother Iosif, his firstDoinarecital took place atPutna Monasteryin 1965.[24]He is known to have taken up the poem in October 1968, at the Eminescu Festival inIpotești,[7][23]with Corlaciu noting his "courage and pathos" in delivering his performance.[9]This defiance was more serious in that context, as it came right after theSoviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.[23]Essayist Nicolae Turtureanu, who attended the 1968 festival, recalls that Romanians from theMoldavian Soviet Socialist Republicwere in attendance, and were alarmed by the performance—since the text mentioned traditional Romanian claims to ownership ofBessarabia;they "thought it was [...] some provocation, that they would be investigated, arrested (upon their return to the 'Republic'), and rushed back into their bus".[23]

In the mid-to-late 1960s, Antal made some returns as an ensemble actor, though, as Pas notes, he was self-effacing, took the "most secondary parts", and was therefore unremarked by the public.[25]This view was partly contradicted by Iosif Antal, who argued in 2007 that his brother had been largely banned from the stage after theDoinaincident, being forever "consumed by [...] all those great roles he dreamed of, and could have acted in".[24]Under contract with Nottara, in 1965 Ludovic appeared alongsideSandu SticlaruinJohn Mortimer'sThe Dock Brief—as argued by theater critic Mircea Alexandrescu, the play was imperfect, in that the two actors seemed not to have chemistry with each other.[26]Antal had also taken his voice acting to the realm ofradio dramaon the national station, and was rated by literary scholar Ion Lungu among the "creators of contemporary radio theater".[27]WithToma Caragiu,Elvira GodeanuandVictor Rebengiuc,he recorded a version ofVictor Ion Popa'sCiuta( "The Deer" ), praised for its originality.[28]AlongsideMitzura Arghezi,he voiced a version of Tudor Arghezi'sBook of Toys,which was later sold as a collectibleLPbyElectrecord.[29]

After 1965, Antal was one of thevoice-oversat Teleenciclopedia, thepopular-scienceshow onRomania's state television.[30]He also achieved notoriety and much public success with his readings fromOctavian Goga,especially later in 1968, which marked Goga's 30th commemoration. This tour took him toCiucea,where his performance was witnessed by Goga's widowVeturia,as well as by philosopherIon Petroviciand sculptorMilița Petrașcu.[31]By contrast, Antal's performance atIon Minulescu's commemoration, in February 1968, was poorly rated by journalistNicolae Carandino,who saw his interpretation as "too clumsy, too technical" for Minulescu's "easy-going" nature.[32]In June 1969, Nottara introduced a number of "literary matinees for the youth" with a stage adaptation ofGarabet Ibrăileanu'sAdela;Antal appeared in it as Doctor Codrescu. WriterGeorge Astaloșpraised his acting, with its "delicate discretion", and noted that Antal had long been absenting from the theater.[33]Carandino was also impressed by Antal, one of "our best thespians". He wrote: "this is the first time we see him granted any sort of more significant role. One would be hard-pressed to understand why theater directors, dramaturges, authors alike, have been neglecting to even note that Ludovic Antal was alivethese past five years[Carandino's emphasis]. "[34]

According to Pascu,Adelawas Antal's most memorable stage performance.[35]Also in June 1969, he was a member of the jury, as well as a guest performer, at the Eminescu Days inBotoșani.[36]His career was soon after cut short by disease: in March 1970, after appearing at one of Petrovici's conferences to read out fromTitu Maiorescu's articles, he coughed up blood;[37]he was then diagnosed withlung cancer.[21]Bedridden at a hospital in Bucharest that spring, he received an impromptu visit from colleaguesValeriu MoisescuandVasile Nițulescu,who jumped over the fence to see him. Moisescu recalled: "lit up by this nocturnal visit of ours, he began to recite to us from Eminescu, in a whispering voice."[38]Antal checked himself out of hospital to attend another Goga festival in Ciucea, but returned to undergo surgery.[39]He was then invited by Veturia Goga to recuperate in Ciucea, but was already in serious condition when the letter reached him,[13][40]and finally died that October.[1][9]

Legacy

[edit]Antal was buried atBellu Cemetery,on 27 October.[1]As Pas reports, the poets of the day proved ungrateful to their deceased friend, as only Corlaciu,Grigore HagiuandIon Horeatook time to write their respective homages.[41]Their tribute was replicated in painting byIacob Lazăr,with the 1971 canvassHomage to Ludovic Antal.[42]Antal had owned an "immense library of poems".[7]His implicit activity as a cultural promoter had made him a collector of manuscripts and autographs, and, according to Corlaciu, his dying wish was for these to be preserved by theRomanian Academy.[9]His surviving family included his one-time wife, Reli Roman,[13]as well as his brother Iosif. In 2005, the later joined other citizens of Butea recognized Ludovic Antal's contribution with a commemorative festival at the local house of culture; here, a "Ludovic Antal Hall" had already been established.[10]Another such ceremony was held in December 2007, by which time the house of culture was home to an Antal-themed exhibit.[24]Commenting in 2008, poet Valeriu Birlan assessed that Antal's memory had been "under a cloud" (într-un con de umbră), and reported not being able to pinpoint his date of birth; he himself recorded Antal's death as having occurred in 1971.[13]

Notes

[edit]- ^abcdef"Ludovic Antal", inRomânia Liberă,27 October 1970, p. 5

- ^abGheorghe Sarău, "Corespondența lui Dimitrie Stelaru" (XXXV), inVatra Veche,Vol. XIII, Issue 1, January 2021, p. 25

- ^Papuc, p. 409

- ^abcdHilda Hencz, "Ködoszlás. Magyar Bukarest a kommunizmus alatt", inSzékelyföld,Vol. XIX, Issue 7, July 2017, p. 137

- ^Papuc, p. 409

- ^"Paul Sava de vorbă cu Alecu Popovici", inTeatrul,Vol. XVIII, Issue 5, May 1973, p. 40

- ^abcdefgh"Interviul nostru. Cu Ludovic Antal, la Ipotești", inClopotul,13 October 1968, p. 2

- ^C. Panaitescu, "O problemă care 'nu interesează': repertoriul teatrelor particulare!", inRampa,17 August 1947, p. 3

- ^abcdeBen Corlaciu,"Zig-Zag", inAteneu,Vol. VII, Issue 11, November 1970, p. 23

- ^abcd"In memoriam Ludovic Antal", inFlacăra Iașului,21 February 2005, p. 4

- ^Pascu, p. 125

- ^T. Ionescu, "Cinstire Poetului", inRomânia Liberă,15 January 1983, p. 2

- ^abcde(in Romanian)Valeriu Birlan,"Scrisoare inedită – Veturia Goga",inConvorbiri Literare,November 2008

- ^Pas, p. 1

- ^Pas, p. 5

- ^"Un nou film artistic românesc", inContemporanul,Issue 258/1951, p. 3

- ^Călin Căliman, "Centenar Victor Iliu", inContemporanul,Vol. XXIII, Issue 10, October 2012, p. 33

- ^Mihai Iacob, "Relief. DocumentarulLuchian",inLuceafărul,Vol. I, Issue 10, December 1958, p. 12

- ^Radu Popescu, "Cronică teatrală.Montserratde Em. Roblès ", inRomânia Liberă,27 March 1957, p. 2

- ^Petre Pandrea,Memoriile mandarinului valah. Jurnal I: 1954–1956,pp. 456–458. Bucharest:Editura Vremea,2011.ISBN978-973-645-440-0

- ^abGheorghe Grigurcu,"Actualități. 'O tristețe impecabilă'", inAcolada,Vol. IX, Issues 7–8, July–August 2015, p. 24

- ^Papuc, pp. 409–410

- ^abcd(in Romanian)Nicolae Turtureanu,"Opinii. Glose la Eminescu",inZiarul de Iași,15 June 2021

- ^abcIosif Antal, "Amintirea lui Ludovic Antal la Butea", inFlacăra Iașului,13 December 2007, p. 4

- ^Pas, p. 1

- ^Mircea Alexandrescu, "Premiere. Teatrul 'C. I. Nottara'. Experimentul 3.3.3. — Pirandello, Mortimer, Schisgal", inTeatrul,Vol. X, Issue 3, March 1965, pp. 35–37

- ^Ion Lungu, "Un muzeu sonor al culturii românești", inSteaua,Vol. XXXIV, Issue 5, 1983, p. 27

- ^Ioana Mălin, "Radio, T.V. Știință, tehnică, literatură", inRomânia Literară,Issue 16/1989, p. 18

- ^C. Eugen, "Actualitatea culturală bucureșteană. Pentru discofili", inInformația Bucureștiului,29 September 1984, p. 2

- ^(in Romanian)"Teleenciclopedia" – de 50 de ani la TVR,TVRrelease, 20 May 2015

- ^Pascu, p. 126

- ^Nicolae Carandino,"Cronică dramatică. Spectacole de poezie", inGazeta Literară,Vol. XV, Issue 6, February 1968, p. 6

- ^George Astaloș,"Teatrul și tineretul. Primul matineu literar la 'Nottara'", inScînteia Tineretului,5 June 1969, p. 4

- ^Nicolae Carandino,"Viața artistică. Cronica spectacolelor din București (Cine ești tu? — Adela — Prețul — Revizorul — Omul în robă — Manevre)", inSteaua,Vol. XX, Issue 8, August 1969, pp. 89–90

- ^Pascu, p. 125

- ^D. Fetescu, "Zilele Eminescu", inClopotul,17 June 1969, p. 2

- ^Pascu, p. 126

- ^Valeriu Moisescu,"Moartea unui artist: Vasile Nițulescu", inTeatrul Azi,Issues 1–2/1991, p. 72

- ^Pascu, p. 126

- ^Pascu, p. 126

- ^Pas, p. 5

- ^Marin Tarangul, "Plastica. Prin galerii", inRomânia Literară,Issue 8/1971, p. 26

References

[edit]- Ion Papuc,Eseuri alese. Articole și recenzii într-o antologie de autor.Bucharest: Editura Mica Valahie, 2017.ISBN978-606-738-059-0

- Ion Pas,"Momente. A iubit Poezia", inRomânia Liberă,1 November 1970, pp. 1, 5.

- Petre Pascu, "Mențiuni și opinii. Ludovic Antal", inSteaua,Vol. XXI, Issue 12, December 1970, pp. 125–126.

External links

[edit]- Ludovic Antal recordingsatDiscogs

- (in Romanian)Antal's rendition of poems by Petrarch,at the Radio Romania archive

- 1924 births

- 1970 deaths

- 20th-century Romanian male actors

- Romanian male stage actors

- Romanian male film actors

- Romanian male voice actors

- Romanian radio actors

- Documentary film people

- Romanian television presenters

- Romanian propagandists

- Romanian patrons of the arts

- Romanian book and manuscript collectors

- People from Iași County

- Romanian people of Csángó descent

- Romanian Roman Catholic priests

- Caragiale National University of Theatre and Film alumni

- Romanian nationalists

- Romanian anti-communists

- Censorship in Romania

- Deaths from lung cancer in Romania

- Burials at Bellu Cemetery