Lungfish

| Lungfish Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

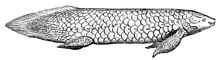

| Queensland lungfish | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Sarcopterygii |

| Clade: | Rhipidistia |

| Clade: | Dipnomorpha Ahlberg,1991 |

| Class: | Dipnoi J. P. Müller,1844 |

| Living families | |

|

Fossil taxa, see text | |

Lungfishare freshwater vertebrates belonging to theclassDipnoi.[1]Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within theOsteichthyes,including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures withinSarcopterygii,including the presence of lobed fins with a well-developed internal skeleton. Lungfish represent the closest living relatives of thetetrapods(which includes living amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals). The mouths of lungfish typically bear tooth plates, which are used tocrush hard shelled organisms.

Today there are only six known species of lungfish, living inAfrica,South America,andAustralia,though they were formerly globally distributed. The fossil record of the group extends into the EarlyDevonian,over 410 million years ago. The earliest known members of the group were marine, while almost all post-Carboniferousrepresentatives inhabit freshwater environments.[2]

Etymology[edit]

Modern Latin from the Greek δίπνοος (dipnoos) with two breathing structures, from δι- twice and πνοή breathing, breath.

Anatomy and morphology[edit]

All lungfish demonstrate an uninterrupted cartilaginousnotochordand an extensively developed palatal dentition.Basal( "primitive") lungfish groups may retain marginal teeth and an ossified braincase, but derived lungfish groups, including all modern species, show a significant reduction in the marginal bones and a cartilaginous braincase. The bones of theskull roofin primitive lungfish are covered in amineralized tissuecalledcosmine,but in post-Devonianlungfishes, the skull roof lies beneath the skin and the cosmine covering is lost. All modern lungfish show significant reductions and fusions of the bones of the skull roof, and the specific bones of the skull roof show nohomologyto the skull roof bones ofray-finned fishesortetrapods.During the breeding season, theSouth American lungfishdevelops a pair of feathery appendages that are actually highly modified pelvic fins. These fins are thought to improve gas exchange around the fish's eggs in its nest.[3]

Throughconvergent evolution,lungfishes have evolved internal nostrils similar to the tetrapods'choana,[4]and a brain with certain similarities to theLissamphibianbrain (except for the Queensland lungfish, which branched off in its own direction about 277 million years ago and has a brain resembling that of theLatimeria).[5]

The dentition of lungfish is different from that of any othervertebrategroup. "Odontodes"on the palate and lower jaws develop in a series of rows to form a fan-shapedocclusionsurface. These odontodes then wear to form a uniform crushing surface. In several groups, including the modernlepidosireniformes,these ridges have been modified to form occluding blades.

The modern lungfishes have a number of larval features, which suggestpaedomorphosis.They also demonstrate the largestgenomeamong the vertebrates.

Modern lungfish all have an elongate body with fleshy, pairedpectoralandpelvicfins and a single unpairedcaudal finreplacing thedorsal,caudal andanalfins of most fishes.

Lungs[edit]

Lungfish have a highly specializedrespiratory system.They have a distinct feature in that their lungs are connected to the larynx and pharynx without a trachea. While other species of fish can breathe air using modified, vascularizedgas bladders,[6]these bladders are usually simple sacs, devoid of complex internal structure. In contrast, the lungs of lungfish are subdivided into numerous smaller air sacs, maximizing the surface area available forgas exchange.

Most extant lungfish species have two lungs, with the exception of the Australian lungfish, which has only one. The lungs of lungfish are homologous to the lungs of tetrapods. As in tetrapods andbichirs,the lungs extend from the ventral surface of theesophagusand gut.[7][8]

Perfusion of water[edit]

Of extant lungfish, only theAustralian lungfishcan breathe through its gills without needing air from its lung. In other species, the gills are too atrophied to allow for adequate gas exchange. When a lungfish is obtainingoxygenfrom its gills, its circulatory system is configured similarly to the common fish. The spiral valve of theconus arteriosusis open, the bypass arterioles of the third and fourth gill arches (which do not actually have gills) are shut, the second, fifth and sixth gill arch arterioles are open, theductus arteriosusbranching off the sixth arteriole is open, and the pulmonary arteries are closed. As the water passes through the gills, the lungfish uses a buccal pump. Flow through the mouth and gills is unidirectional. Blood flow through the secondary lamellae is countercurrent to the water, maintaining a more constant concentration gradient.

Perfusion of air[edit]

When breathing air, the spiral valve of the conus arteriosus closes (minimizing the mi xing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood), the third and fourth gill arches open, the second and fifth gill arches close (minimizing the possible loss of the oxygen obtained in the lungs through the gills), the sixth arteriole's ductus arteriosus is closed, and the pulmonary arteries open. Importantly, during air breathing, the sixth gill is still used in respiration; deoxygenated blood loses some of its carbon dioxide as it passes through the gill before reaching the lung. This is because carbon dioxide is more soluble in water. Air flow through the mouth is tidal, and through the lungs it is bidirectional and observes "uniform pool" diffusion of oxygen.

Ecology and life history[edit]

Lungfish areomnivorous,feeding on fish,insects,crustaceans,worms,mollusks,amphibiansand plant matter. They have anintestinal spiral valverather than a truestomach.[9]

African and South American lungfish are capable of surviving seasonal drying out of their habitats by burrowing into mud andestivatingthroughout the dry season. Changes inphysiologyallow it to slow itsmetabolismto as little as one sixtieth of the normal metabolic rate, and protein waste is converted fromammoniato less-toxicurea(normally, lungfish excrete nitrogenous waste as ammonia directly into the water).

Burrowing is seen in at least one group of fossil lungfish, theGnathorhizidae.

Lungfish can be extremely long-lived. AQueensland lungfishcalled "Granddad"[10]at theShedd AquariuminChicagowas part of the permanent live collection from 1933 to 2017 after a previous residence at theSydney Aquarium;[11]at about 95 years old,[10]it was euthanized following a decline in health consistent with old age.[11]

As of 2022, the oldest lungfish, and probably the oldest aquarium fish in the world is "Methuselah", an Australian lungfish 4 feet (1.2 m) long and weighing around 40 pounds (18 kg). Methuselah is believed to be female, unlikeits namesake,and is estimated to be over 90 years old.[10]

Evolution[edit]

About 420 million years ago, during theDevonian,thelast common ancestorof both lungfish and thetetrapodssplit into two separate evolutionary lineages, with the ancestor of the extantcoelacanthsdiverging a little earlier from asarcopterygianprogenitor.[12]YoungolepisandDiabolepis,dating to 419–417 million years ago, during Early Devonian (Lochkovian), are the currently oldest known lungfish, and show that the lungfishes had adapted to a diet including hard-shelled prey (durophagy) very early in their evolution.[13]The earliest lungfish were marine. Almost all post-Carboniferouslungfish inhabit or inhabited freshwater environments. There were likely at least two transitions amongst lungfish from marine to freshwater habitats. The last common ancestor of all living lungfish likely lived sometime between the LateCarboniferous[2]and theJurassic.[14]Lungfish remained present in the northernLaurasianlandmasses into theCretaceousperiod.[15]

Extant lungfish[edit]

| Family | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

| Neoceratodontidae | Neoceratodus | Queensland lungfish |

| Lepidosirenidae | Lepidosiren | South American lungfish |

| Protopteridae | Protopterus | Marbled lungfish |

| Gilled lungfish | ||

| West African lungfish | ||

| Spotted lungfish |

TheQueensland lungfish,Neoceratodus forsteri,isendemicto Australia.[16]Fossil records of this group date back 380 million years, around the time when thehigher vertebrateclasses were beginning to evolve.[17]Fossils of lungfish belonging to the genusNeoceratodushave been uncovered in northernNew South Wales,indicating that the Queensland lungfish has existed in Australia for at least 100 million years, making it aliving fossiland one of the oldest living vertebrate genera on the planet.[17][18]It is the most primitive surviving member of the ancient air-breathing lungfish (Dipnoi) lineages.[17][19]The five other freshwater lungfish species,fourin Africa andonein South America, are very different morphologically toN. forsteri.[17]The Queensland lungfish can live for several days out of the water if it is kept moist, but will not survive total water depletion, unlike its African counterparts.[16]

TheSouth American lungfish,Lepidosiren paradoxa,is the single species of lungfish found inswampsand slow-moving waters of theAmazon,Paraguay,and lowerParaná Riverbasinsin South America. Notable as anobligateair-breather, it is the sole member of its family native to the Americas. Relatively little is known about the South American lungfish,[20]orscaly salamander-fish.[21]When immature it is spotted with gold on a black background. In the adult this fades to a brown or gray color.[22]Its tooth-bearingpremaxillaryandmaxillarybones are fused like other lungfish. South American lungfishes also share an autostylic jaw suspension (where thepalatoquadrateis fused to thecranium) and powerful adductor jaw muscles with the extant lungfish (Dipnoi). Like theAfrican lungfishes,this species has an elongate, almost eel-like body. It may reach a length of 125 centimetres (4 ft 1 in). Thepectoral finsare thin and threadlike, while the pelvic fins are somewhat larger, and set far back. The fins are connected to the shoulder by a single bone, which is a marked difference from most fish, whose fins usually have at least four bones at their base; and a marked similarity with nearly all land-dwelling vertebrates.[23]They have the lowest aquatic respiration of all extant lungfish species,[24]and their gills are greatly reduced and essentially non-functional in the adults.[25]

Themarbled lungfish,Protopterus aethiopicus,is found in Africa. The marbled lungfish is smooth, elongated, and cylindrical with deeply embeddedscales.The tail is very long and tapers at the end. They are the largest of the African lungfish species as they can reach a length of up to 200 cm.[26]The pectoral and pelvic fins are also very long and thin, almost spaghetti-like. The newly hatched young have branched external gills much like those of newts. After 2 to 3 months the young transform (calledmetamorphosis) into the adult form, losing theexternal gillsfor gill openings. These fish have a yellowish gray or pinkish toned ground color with dark slate-gray splotches, creating a marbling or leopard effect over the body and fins. The color pattern is darker along the top and lighter below.[27]The marbled lungfish'sgenomecontains 133 billionbase pairs,making it the largest known genome of anyvertebrate.The onlyorganismsknown to have more base pairs are theprotistPolychaos dubiumand the flowering plantParis japonicaat 670 billion and 150 billion, respectively.[28]

Thegilled lungfish,Protopterus amphibiusis a species of lungfish found inEast Africa.[29][30]It generally reaches only 44 centimetres (17 inches) long, making it the smallestextantlungfish in the world.[31]This lungfish is uniform blue, or slate grey in colour. It has small or inconspicuous black spots, and a pale grey belly.[32]

Thewest African lungfish,Protopterus annectens,is a species of lungfish found in West Africa.[33][34][35]It has a prominentsnoutand smalleyes.Its body is long andeel-like,some 9–15 times the length of the head. It has two pairs of long, filamentousfins.Thepectoral finshave a basal fringe and are about three times the head length, while itspelvic finsare about twice the head length. In general, three externalgillsare insertedposteriorto thegill slitsand above the pectoral fins. It hascycloid scalesembedded in the skin. There are 40–50 scales between theoperculumand theanusand 36–40 around the body before the origin of thedorsal fin.It has 34–37 pairs ofribs.Thedorsalside is olive or brown in color and theventralside is lighter, with great blackish or brownish spots on the body and fins except on its belly.[36]They reach a length of about 100 cm in the wild.[37]

Thespotted lungfish,Protopterus dolloi,is a species of lungfish found in Africa. Specifically, it is found in theKouilou-NiariBasin of theRepublic of the CongoandOgoweRiver basin inGabon.It is also found in the lower and MiddleCongo River Basins.[38]Protopterus dolloicanaestivateon land by surrounding itself in a layer of driedmucus.[39][40]It can reach a length of up to 130 cm.[38]

Taxonomy[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(October 2020) |

The relationship of lungfishes to the rest of thebony fishis well understood:

- Lungfishes are most closely related toPowichthys,and then to thePorolepiformes.

- Together, these taxa form theDipnomorpha,the sister group to theTetrapodomorpha.

- Together, these form theRhipidistia,the sister group to thecoelacanths.

Recent molecular genetic analyses strongly support a sister relationship of lungfishes and tetrapods (Rhipidistia), with coelacanths branching slightly earlier.[41][42]

The relationships among lungfishes are significantly more difficult to resolve. While Devonian lungfish had enough bone in the skull to determine relationships, post-Devonian lungfish are represented entirely by skull roofs and teeth, as the rest of the skull iscartilaginous.Additionally, many of the taxa already identified may not bemonophyletic.

Phylogeny after Kemp, Cavin & Guinot, 2017[2]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram after Brownstein et al. 2023[14]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"ITIS - Report: Dipnoi".itis.gov.Retrieved13 March2023.

- ^abcKemp, Anne; Cavin, Lionel; Guinot, Guillaume (1 April 2017)."Evolutionary history of lungfishes with a new phylogeny of post-Devonian genera".Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.471:209–219.Bibcode:2017PPP...471..209K.doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.12.051.ISSN0031-0182.

- ^Piper, Ross(2007).Extraordinary Animals: An encyclopedia of curious and unusual animals.Greenwood Press.

- ^"Evolution: On the evolution of internal nostrils (choanae)".Science-Week.Archived fromthe originalon 20 March 2012.Retrieved23 September2011.

- ^Clement Alice M (2014)."The first virtual cranial endocast of a lungfish (sarcopterygii:dipnoi) ".PLOS ONE.9(11): e113898.Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k3898C.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113898.PMC4245222.PMID25427173.10.1371.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^Colleen Farmer (1997),"Did lungs and the intracardiac shunt evolve to oxygenate the heart in vertebrates"(PDF),Paleobiology,23(3): 358–372,doi:10.1017/s0094837300019734,S2CID87285937,archived fromthe original(PDF)on 11 June 2010

- ^Wisenden, Brian (2003)."Chapter 24: The Respiratory System – Evolution Atlas".Human Anatomy.Pearson Education, Inc. Archived fromthe originalon 25 November 2010.

- ^Hilber, S.A. (2007)."Gnathostome form & function".Vertebrate Zoology Lab. U. Florida. Lab 2. Archived fromthe originalon 20 July 2011.Retrieved31 December2010.

- ^Purkerson, M.L. (1975). "Electron microscopy of the intestine of the African lungfish,Protopterus aethiopicus".The Anatomical Record.182(1): 71–89.doi:10.1002/ar.1091820109.PMID1155792.S2CID44787314.

- ^abc"Methuselah: Oldest aquarium fish lives in San Francisco and likes belly rubs".The Guardian.26 January 2022.

- ^ab"Chicago aquarium euthanizes 90 year-old lungfish".Star Tribune.Archived fromthe originalon 7 February 2017.Retrieved6 February2017.

- ^Australian lungfish has largest genome of any animal sequenced so far - New Scientist

- ^Cui, Xindong; Friedman, Matt; Qiao, Tuo; Yu, Yilun; Zhu, Min (2 May 2022)."The rapid evolution of lungfish durophagy".Nature Communications.13(1): 2390.doi:10.1038/s41467-022-30091-3.ISSN2041-1723.PMC9061808.PMID35501345.

- ^abBrownstein, Chase Doran; Harrington, Richard C; Near, Thomas J. (July 2023)."The biogeography of extant lungfishes traces the breakup of Gondwana".Journal of Biogeography.50(7): 1191–1198.doi:10.1111/jbi.14609.ISSN0305-0270.

- ^Frederickson, Joseph A.; Cifelli, Richard L. (January 2017)."New Cretaceous lungfishes (Dipnoi, Ceratodontidae) from western North America".Journal of Paleontology.91(1): 146–161.doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.131.ISSN0022-3360.S2CID131962612.

- ^abLake, John S. (1978).Australian Freshwater Fishes.Nelson Field Guides. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson Australia Pty. Ltd. p. 12.

- ^abcdAllen, G.R.; Midgley, S.H.; Allen, M. (2002). Knight, Jan; Bulgin, Wendy (eds.).Field Guide to the Freshwater Fishes of Australia.Perth, W.A.: Western Australia Museum. pp. 54–55.

- ^Kemp, Anne; Berrell, Rodney (3 May 2020)."A New Species of Fossil Lungfish (Osteichthyes: Dipnoi) from the Cretaceous of Australia".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.40(3): e1822369.doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1822369.ISSN0272-4634.S2CID225133051.

- ^Frentiu, F.D.; Ovenden, J.R.; Street, R. (2001). "Australian lungfish (Neoceratodus forsteri:Dipnoi) have low genetic variation at allozyme and mitochondrial DNA loci: A conservation alert? ".Conservation Genetics.2.2:63–67.doi:10.1023/A:1011576116472.S2CID22778872.

- ^Haeckel, Ernst Heinrich Philipp August;Lankester, Edwin Ray; Schmitz, L. Dora (1892).The History of Creation, or, the Development of the Earth and Its Inhabitants by the Action of Natural Causes.D. Appleton. pp. 289, 422.

A popular exposition of the doctrine of evolution in general, and of that of Darwin, Goethe, and Lamarck in particular. From the 8th German edition by Ernst Haeckel

- ^Guenther, Konrad (1931).A Naturalist in Brazil.Translated byMiall, Bernard.Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 275, 399.

The record of a year's observation of her flora, her fauna, and her people.

- ^"South American Lungfish".Animal World.

- ^"Your Inner Fish" Neil Shubin, 2008,2009,Vintage, p.33

- ^The differential cardio-respiratory responses to ambient hypoxia and systemic hypoxaemia in the South American lungfish, Lepidosiren paradoxa

- ^Bruton, Michael N. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.).Encyclopedia of Fishes.San Diego: Academic Press. p. 70.ISBN978-0-12-547665-2.

- ^Fishbase.org

- ^Animal-World."Marbled Lungfish".Animal World.

- ^IJ Leitch (13 June 2007). "Genome sizes through the ages".Heredity.99(2). Nature Publishing Group: 121–122.doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800981.ISSN0018-067X.PMID17565357.S2CID5406138.

- ^EOL.org(Retrieved 19 February 2010.)

- ^Fishbase.org(Retrieved 19 February 2010.)

- ^Primitive FishesArchived11 December 2008 at theWayback MachineRetrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^Fishbase.org(Retrieved 25 September 2010.)

- ^EOL.org(Retrieved 13 May 2010.)

- ^Fishbase.org(Retrieved 13 May 2010.)

- ^"Protopterus annectens, West African lungfish: fisheries, aquaculture".FishBase.

- ^"West African Lungfish (Protopterus annectens annectens) - Information on West African Lungfish - Encyclopedia of Life".Encyclopedia of Life.[permanent dead link]

- ^Primitivefishes (Retrieved May 13, 2010.)Archived11 October 2010 at theWayback Machine

- ^abFishbase.org

- ^Brien, P. (1959). Ethologie du Protopterus dolloi(Boulenger) et de ses larves. Signification des sacs pulmonaires des Dipneustes. Ann. Soc. R. Zool. Belg. 89, 9-48.

- ^Poll, M. (1961). Révision systématique et raciation géographique des Protopteridae de l’Afrique centrale. Ann. Mus. R. Afr. Centr. Sér. 8. Sci. Zool. 103, 3-50.

- ^Amemiya, Chris T.; Alföldi, Jessica; Lee, Alison P.; Fan, Shaohua; Philippe, Hervé; MacCallum, Iain; et al. (18 April 2013)."The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution".Nature.496(7445): 311–316.Bibcode:2013Natur.496..311A.doi:10.1038/nature12027.PMC3633110.PMID23598338.

- ^Takezaki, N.; Nishihara, H. (2017)."Support for lungfish as the closest relative of tetrapods by using slowly evolving ray-finned fish as the outgroup".Genome Biology and Evolution.9(1): 93–101.doi:10.1093/gbe/evw288.PMC5381532.PMID28082606.

Further reading[edit]

- Ahlberg, P.E.; Smith, M.M.; Johanson, Z. (2006). "Developmental plasticity and disparity in earlydipnoan(lungfish) dentitions ".Evolution and Development.8(4): 331–349.doi:10.1111/j.1525-142x.2006.00106.x.PMID16805898.S2CID28339324.

- Palmer, Douglas, ed. (1999).The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs & Prehistoric Creatures, A visual who's who of prehistoric life.Great Britain: Marshall Editions Developments Limited. p. 45.

- Schultze, H.P.; Chorn, J. (1997)."The Permo-Carboniferous genusSagenodusand the beginning of modern lungfish ".Contributions to Zoology.61(7): 9–70.doi:10.1163/18759866-06701002.

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002)."A compendium of fossil marine animal genera".Bulletins of American Paleontology.364:560. Archived fromthe originalon 20 February 2009.Retrieved17 May2011.

External links[edit]

- Kemps, Anne, Dr."Lungfish Information site".Archived fromthe originalon 2 August 2014.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Dipnoiformes".Palaeos.Archived fromthe originalon 13 March 2006.

- "Dipnoi".University of California Museum of Paleontology.

- "Tree of life illustration showing lungfish's relation to other organisms".tellapallet.Archived fromthe originalon 23 January 2009.

- "Lungfish video".YouTube.Archivedfrom the original on 18 November 2021.