Lycia

| Lycia Lukka Likya 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖(Trm̃mis) Λυκία(Lykia) | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Region of Anatolia | |

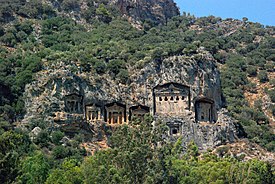

Lycian rock cut tombs of Dalyan | |

| Location | Teke Peninsula,Western Taurus Range, SouthernAnatolia,Turkey |

| Languages | Lycian,Greek |

| Successivecapitals[citation needed] | Xanthos(Kınık)Patara(Gelemiş) |

| Achaemenidsatrapy | Cilicia&Lydia |

| Roman protectorate | Lycian League |

| Roman province | Lycia, then Lycia with other states |

| Byzantine eparchy | Lykia |

| |

Lycia(Lycian:𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖Trm̃mis;Greek:Λυκία,Lykia;Turkish:Likya) was ahistorical regioninAnatoliafrom 15–14th centuries BC (asLukka) to 546 BC. It bordered theMediterranean Seain what is today theprovincesofAntalyaandMuğlainTurkeyas well some inland parts ofBurdur Province.The region was known to history from theLate Bronze Agerecords ofancient Egyptand theHittite Empire.

Lycia was populated by speakers ofLuwic languages.Written records began to be inscribed in stone in theLycian languageafter Lycia's involuntary incorporation into theAchaemenid Empirein theIron Age.At that time (546 BC) the Luwian speakers were displaced as Lycia received an influx of Persian speakers.

The many cities in Lycia were wealthy as shown by their elaborate architecture starting at least from the 5th century BC and extending to the Roman period.

Lycia fought for the Persians in thePersian Wars,but on the defeat of theAchaemenid Empireby the Greeks, it became intermittently a free agent. After a brief membership in theAthenian Empire,it seceded and became independent (its treaty with Athens had omitted the usual non-secession clause), was under the Persians again, revolted again, was conquered byMausolusofCaria,returned to the Persians, and finally fell underMacedonianhegemonyupon the defeat of the Persians byAlexander the Great.Due to the influx of Greek speakers and the sparsity of the remaining Lycian speakers, Lycia was rapidlyHellenizedunder the Macedonians, and the Lycian language disappeared from inscriptions and coinage.

On defeatingAntiochus III the Greatin 188 BC, theRoman Republicgave Lycia toRhodesfor 20 years, taking it back in 168 BC. In these latter stages of the Roman Republic, Lycia came to enjoy freedom as a Romanprotectorate.The Romans validatedhome ruleofficially under the Lycian League in 168 BC. This native government was an earlyfederationwith republican principles; these later came to the attention of the framers of theUnited States Constitution,influencing their thoughts.[1]

Despite home rule, Lycia was not a sovereign state and had not been since its defeat by theCarians.In 43 AD the Roman emperorClaudiusdissolved the league, and Lycia was incorporated into theRoman Empirewith provincial status. It became aneparchyof the Eastern, orByzantine Empire,continuing to speak Greek even after being joined by communities ofTurkish languagespeakers in the early 2nd millennium. After thefall of the Byzantine Empirein the 15th century, Lycia was under theOttoman Empire,and was inherited by theTurkish Republicon theDissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

Geography[edit]

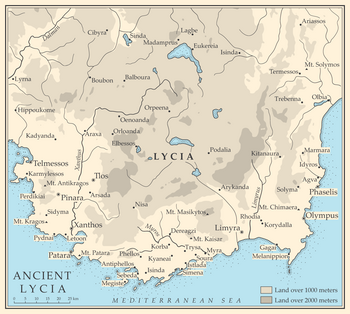

The borders of Lycia varied over time, but at its centre was theTeke peninsulaof southwestern Turkey, which juts southward into theMediterranean Sea,bounded on the west by theGulf of Fethiye,and on the east by theGulf of Antalya.Lycia comprised what is now the westernmost portion ofAntalyaProvince, the easternmost portion ofMuğla Province,and the southernmost portion ofBurdurProvince. In ancient times the surrounding districts were, from west to east,Caria,Pisidia,andPamphylia,all equally as ancient, and each speaking its ownAnatolian language.

The name of the Teke Peninsula comes from the former name of Antalya Province, which wasTeke Province,named from the Turkish tribe that settled in the region.

Physical geography[edit]

Four ridges extend from northeast to southwest, roughly, forming the western extremity of theTaurus Mountains.Furthest west of the four are Boncuk Dağlari, or 'the Boncuk Mountains', extending from aboutAltinyayla, Burdur,southwest to about Oren north ofFethiye.This is a fairly low range peaking at about 2,340 m (7,680 ft). To the west of it the steep gorges ofDalaman Çayi('the Dalaman River'), the ancient Indus, formed the traditional border between Caria and Lycia. The stream, 229 km (142 mi) long, enters the Mediterranean to the west of modern-dayDalaman.Upstream it is dammed in four places, after an origin in the vicinity of Sarikavak inDenizliProvince.

The next ridge to the east is Akdağlari, 'the White Mountains', about 150 km (93 mi) long, with a high point at Uyluktepe, "Uyluk Peak", of 3,024 m (9,921 ft). This massif may have been ancient Mount Cragus. Along its western side flows Eşen Çayi, "the Esen River", anciently theXanthos,Lycian Arñna, originating in the Boncuk Mountains, flowing south, and transecting the several-mile-long beach atPatara.The Xanthos Valley was the country called Tŗmmis in dynastic Lycia, from which the people were the Termilae or Tremilae, or Kragos in the coin inscriptions of Greek Lycia: Kr or Ksan Kr. The name of western Lycia was given byCharles Fellowsto it and points of Lycia west of it.

The next ridge to the east, Beydağlari, 'the Bey Mountains', peaks at Kizlarsevrisi, 3,086 m (10,125 ft), the highest point of the Teke Peninsula. It is most likely the ancient Masicytus range. Between Beydağlari and Akdağlari is an upland plateau, Elmali, where ancient Milyas was located. The elevation of the town of Elmali, which means 'Apple Town,' from the density of fruit-bearing groves in the region, is 1,100 m (3,600 ft), which is the highest part of the valley below it. Fellows considered the valley to be central Lycia.

The Akçay, or 'White River', the ancient Aedesa, brought water from the slopes to the plain, where it pooled in two lakes below the town, Karagöl and Avlangöl. Currently the two lakes are dry, the waters being captured on an ongoing basis by irrigation systems for the trees. The Aedesa once drained the plain through a chasm to the east, but now flows entirely through pipelines covering the same route, but emptying into the water supplies of Arycanda and Arif. An effort has been made to restore some of the cedar forests cleared in antiquity.[3]

The easternmost ridge extends along the east coast of the Teke Peninsula, and is called, generally, Tahtali Dağlari, "The Tahtali Mountains." The high point within them is Tahtali Dağ, elevation 2,366 m (7,762 ft), dubbed "Mount Olympus" in antiquity by the Greeks, rememberingMount Olympusin Greece.[4]These mountains create a rugged coastline called by Fellows eastern Lycia. Much of it has been reserved as Olimpos Beydağlari Parki. Within the park on the slopes of Mount Olympus is a U-shaped outcrop,Yanartaş,aboveCirali,from whichmethanegas, naturally perpetually escaping from below through the rocks, feeds eternal flames. This is the location of ancientMount Chimaera.

Through thecul-de-sacbetween Baydağlari and Tahtalidağlari, the Alakir Çay ('Alakir River'), the ancient Limyra, flows to the south trickling from the broad valley under superhighway D400 near downtownKumlucaacross a barrier beach into the Mediterranean. This configuration is entirely modern. Upstream the river is impounded behind Alakir Dam to form an urban-size reservoir. Below the reservoir a braided stream alternates with a single, small channel flowing through irrigated land. The wide bed gives an indication of the former size of the river. Upstream from the reservoir the stream lies in an unaltered gorge, flowing from the slopes of Baydağlari. The ancient route to Antalya goes up the valley and over the cul-de-sac, as the coast itself is impassible except by boat. The valley was the seat of ancient Solymus, home of the Solymi.

Demography[edit]

There are at least 381 ancient settlements in the broader region of Lycia-Pamphylia, with the vast majority of these in Lycia.[5]These are situated either along the coastal strip in the protecting coves or on the slopes and hills of the mountain ranges. They are often difficult to access, which in ancient times was a defensive feature. The rugged coastline favored well-defended ports from which, in troubled times, Lycian pirate fleets sallied forth.

The principal cities of ancient Lycia wereXanthos,Patara,Myra,Pinara,TlosandOlympos(each entitled to three votes in the Lycian League) andPhaselis.Cities such asTelmessosandKryawere sometimes listed by Classical authors as Carian and sometimes as Lycian.

Features and sights of interest[edit]

Although the 2nd-century BC dialogueErōtesfound the cities of Lycia "interesting more for their history than for their monuments, since they have retained none of their former splendor," many relics of theLyciansremain visible today. These relics include the distinctiverock-cut tombsin the sides of cliffs. TheBritish MuseuminLondoncontains one of the best collections of Lycian artifacts.Letoon,an important center in Hellenic times of worship for the goddessLetoand her twin children,ApolloandArtemis,and nearby Xanthos, ancient capital of Lycia, constitute aUNESCO World Heritage Site.[6]

Turkey's firstwaymarkedlong-distance footpath, theLycian Way,follows part of the coast of the region. The establishment of the path was a private initiative by a British/Turkish woman called Kate Clow. It is intended to supportsustainable tourismin smaller mountain villages which are in the process of depopulation. Since it is mainly walked in March – June and Sept–Nov, it also has lengthened the tourism season. The Turkish Culture and Tourism Ministry promotes the Lycian coast as part of theTurkish Rivieraor the Turquoise Coast, but the most important part of this is further west near Bodrum. This coast features rocky or sandy beaches at the bases of cliffs and settlements in protected coves that cater to the yachting industry.

-

Telmessos rock tomb. The sign on site says the tombs date from about 400 BC

-

Rock-cut tombs inMyra

-

Ogival rock-cut tomb atPinara,4th century BC

-

Ancient Lycian tomb inKaş

-

Ancient Greek theater atOinoanda

-

Lycian tomb inKaş

-

Lycian tomb in Fethiye

-

Lycian tomb inKastellorizo

Ancient language[edit]

The eponymous inhabitants of Lycia, theLycians,spoke Lycian, a member of theLuwianbranch of theAnatolian languages,a subfamily of theIndo-Europeanfamily. Lycian has been attested only between about 500 BC and no later than 300 BC, in aunique Alpha betdevised for the purpose from the Greek Alpha bet of Rhodes. However, the Luwian languages originated in Anatolia during the 2nd millennium BC. The country was known by the name ofLukkathen, and was sometimes under Hittite rule.

At about 535 BC, before the first appearance of attested Lycian, theAchaemenid Empireoverran Lycia. Despite its resistance, because of which the population of Xanthos was decimated, Lycia became part of the Persian Empire. The first coins with Lycian letters on them appeared not long before 500 BC.[9]Lycia prospered under a monarchy set up by the Persians. Subsequently, the Lycians were verbose in stone, carving memorial, historical and governmental inscriptions. Not all of these can yet be entirely understood, due to remaining ignorance of the language. The term "dynastic period" is used. If the government was any sort of federal democracy, there is no evidence of it, as the term "dynastic" suggests.

Lycia hosted a small enclave of Dorian Greeks for some centuries andRhodeswas mainly inhabited by Dorians at the time. After the defeat of the Persians by the Greeks, Lycia became open to further Greek settlement. During this period, inscriptions in Lycian diminished, while those in Greek multiplied. Complete assimilation to Greek occurred sometime in the 4th century, after Lycia had come under the control ofAlexander the Greatand his fellow Macedonians.[11]There is no agreement yet on which inscription in the Lycian language is the very last, but nothing dated after the year 300 BC has yet been found.

Subsequently, the Lycians were vassalized by theRoman Republic,which allowed the Lycians home rule under their own language, which at that point was Greek. Lycia continued to exist as a vassal state under theRoman Empireuntil its final division after the death ofTheodosius Iat which point it became a part of theByzantine EmpireunderArcadius.After the fall of the Byzantines in the 15th century, Lycia fell under the control of theOttoman Empire;Turkish colonization of the area soon followed. Turkish and Greek settlements existed side-by-side, each speaking their own language.

All Greek-speaking enclaves in Anatolia were exchanged for Turkish speakers in Greece during the final settlement of the border with Greece at the beginning of theTurkish Republicin 1923. The Turks had won wars against both Greece and Armenia in the preceding few years, settling the issue of whether the coast of Anatolia was going to be Greek or Turkish. The intent of theTreaty of Lausanne (1923)was to define borders that would not leave substantial populations of one country in another. Some population transfers were enforced. Former Greek villages still stand as ghost towns in Lycia.

History[edit]

Bronze Age[edit]

During theLate Bronze Age,Lycia was part of theLukka landsknown fromHittiteandancient Egyptianrecords. The toponyms Lukka and Lycia are believed to be cognate, as are the names of numerous Lukkan and Lycian settlements.[12][13][14]

The Lukka lands were never a unified kingdom, instead having a decentralized political structure. Archaeological remains of the Lukka people are sparse. The Lukka people were famously fractious, with Hittite and Egyptian records describing them as raiders, rebels, and pirates. Lukka people fought against the Hittites as part of theAssuwa confederation,later fought for the Hittites in theBattle of Kadesh,and are listed among the groups known to modern scholars as theSea People.[15][16][17]

Dynastic period[edit]

Acquisition by Cyrus the Great (circa 540 BC)[edit]

Herodotus writes more credibly of contemporaneous events, especially where they concerned his native land. Asia Minor had been partly conquered byIranian peoples,first theScythians,later theMedes.The latter were defeated by thePersians,who incorporated them and their lands into the newPersian Empire.Cyrus the Great,founder of theAchaemeniddynasty, resolved to complete the conquest of Anatolia as a prelude to operations further west, to be carried out by his successors. He assigned the task toHarpagus,a Median general, who proceeded to subdue the various states of Anatolia, one by one, some by convincing them to submit, others through military action.

Arriving at the southern coast of Anatolia in 546 BC, the army of Harpagus encountered no problem with the Carians and their immediate Greek neighbors and alien populations, who submitted peacefully. In theXanthosValley an army of Xanthian Greeks sallied out to meet them, fighting determinedly, although vastly outnumbered. Driven into the citadel, they collected all their property, dependents and slaves into a central building, and burned them up. Then, after taking an oath not to surrender, they died to a man fighting the Persians, foreshadowing and perhaps setting an example for Spartan conduct at theBattle of Thermopylaea few generations later.

Archaeological evidence indicates there was a major fire on the acropolis of Xanthos in the mid-6th century BC but, as Antony Keen points out, there is no way to connect that fire with the event presented by Herodotus. It might have been another fire.[18]The Caunians, says Herodotus, followed a similar example immediately after.[19]If there was an attempt by any of the states of Lycia to join forces, as happened in Greece 50 years later, there is no record of it, suggesting that no central government existed. Each country awaited its own fate alone.

Herodotus also says or implies that 80 Xanthian families were away at the time, perhaps with the herd animals in alpine summer pastures (pure speculation), but helped repopulate the place. However, he reports, the Xanthians of his time were mainly descended from non-Xanthians. Looking for any nuance that might shed light on the repopulation of Xanthos, Keen interprets Herodotus' "those Lycians who now say that they are Xanthians" to mean that Xanthos was repopulated by other Lycians (and not by Iranians or other foreigners).[20]Herodotus said nothing of the remainder of Lycia; presumably, that is true because they submitted without further incident. Lycia was well populated and flourished as a Persian satrapy; moreover, they spoke mainly Lycian.

The Harpagid theory[edit]

The Harpagid Theory was initiated byCharles Fellows,discoverer of theXanthian Obelisk,and person responsible for the transportation of the Xanthian Marbles from Lycia to theBritish Museum.Fellows could not read the Lycian inscription, except for one line identifying a person of illegible name, to whom the monument was erected, termed the son of Arppakhu in Lycian, equivalent to GreekHarpagos.Concluding that this person was the conqueror of Lycia in 546, Fellows conjectured that Harpagos had been made permanent satrap of Lycia for his services; moreover, the position was hereditary, creating a Harpagid Dynasty. This theory prevailed nearly without question for several generations.

To the inscriptions of the Xanthian Obelisk were added those of theLetoon trilingual,which gave a sequel, as it were, to the names on the obelisk. Studies of coin legends, initiated by Fellows, went on. Currently, most (but not all) of the Harpagid Theory has been rejected. The Achaemenids utilized no permanent satrapies; the political circumstances changed too often. The conqueror of new lands was seldom made their satrap; he went on to other conquests. It was not the Persian custom to grant hereditary satrapies; satrap was only a step in thecursus honorum.And finally, a destitute mountain country would have been a poor reward for Cyrus' best general.[20]The main evidence against the Harpagid Theory (as Keen calls it) is the reconstruction of the name of the Xanthian Obelisk's deceased as Lycian Kheriga, Greek Gergis (Nereid Monument), a king reigning approximately 440–410 BC, over a century later than the conqueror of Lycia.

The next logical possibility is that Kheriga's father, Arppakhu, was a descendant of the conqueror. In opposition, Keen reconstructs the dynastic sequence from coin inscriptions as follows.[21]Kheriga had two grandfathers, Kuprlli and Kheriga. The younger Kheriga was the successor of Kuprlli. The latter's son, therefore, Kheziga, who was Kheriga's uncle, must have predeceased Kuprlli. Arppakhu is listed as regnant on two other inscriptions, but he did not succeed Kuprlli. He must therefore have married a daughter of Kuprlli, and have also predeceased the long-lived Kuprlli. The latter then was too old to reign de facto. On the contemporaneous deaths of both him and his son-in-law, Kheriga, named after his paternal grandfather, acquired the throne.

Kuprlli was the first king recorded for certain (there was an earlier possible) in the coin legends. He reigned approximately 480–440. Harpagos was not related by blood. The conqueror, therefore, was not the founder of the line, which was not Harpagid. An Iranian family, however, producing some other Harpagids, did live in Lycia and was of sufficient rank to marry the king's daughter. As to whether the Iranian family were related to any satrap, probably not. Herodotus said that Satrapy 1 (the satrapies were numbered) consisted of Ionia, Magnesia, Aeolia, Caria, Lycia, Milya, and Pamphylia, who together paid a tax of 400 silver talents. This satrapy was later broken up and recombined.[22]Keen hypothesizes that since Caria had responsibility for the King's Highway through Lycia, Lycia and Caria were a satrapy.[23]

The Lycian monarchy[edit]

TheAchaemenid Persianpolicy toward Lycia was hands-off.[23]There was not even a satrap stationed in the country. The reason for this tolerance after such a determined initial resistance is that the Iranians were utilizing another method of control: the placement of aristocratic Persian families in a region to exercise putative home rule. There is some evidence that the Lycian population was not as docile as the Persian hand-off policy would suggest. A section of thePersepolis Administrative Archivescalled the Persepolis Fortification Tablets, regarding the redistribution of goods and services in the Persepolispalace economy,mentions some redistributed prisoners of war, among whom were the Turmirla or Turmirliya, Lycian Trm̃mili, "Lycians." They lived during the reign ofDarius I(522–486), the tablets dating from 509.[25]

For closer attention to their conquered, the Persian government preferred to establish aclient state,setting up a monarchy under their control. The term "dynast"has come into use among English-speaking scholars, but that is not a native term. The Lycian inscriptions indicate the monarch was titled xñtawati, more phonetically khñtawati. The holders of this title can be traced in coin legends, having been given the right to coin. Lycia had a single monarch, who ruled the entire country from a palace at Xanthos. The monarchy was hereditary, hence the term" dynast. "It was utilized by Persia as a means of transmitting Persian policy. It must have been they who put down local resistance and transported the prisoners to Persepolis, or ordered them transported. Some members of the dynasty were Iranian, but mainly it was native Lycian. If the survivors of 546 were in fact herdsmen (speculation), then all the Xanthian nobility had perished, and the Persians must have designated some other Lycian noble, whom they could trust.[30]

The first dynast is believed to be the person mentioned in the last line of the Greek epigram inscribed on theXanthian Obelisk,which says "this monument has brought glory to the family (genos) of ka[]ika," which has a letter missing. It is probably not *karikas, for Kherika, as the latter is translated in theLetoon trilingualas Gergis. A more likely possibility is *kasikas for Kheziga, the same as Kheriga's uncle, the successor to Kuprlli, who predeceased him.[31]

Herodotus mentioned that the leader of the Lycian fleet underXerxesin theSecond Persian Warof 480 BC wasKuberniskos Sika,previously interpreted as "Cyberniscus, the son of Sicas," two non-Lycian names.[32]A slight regrouping of the letters obtainskubernis kosika,"Cybernis, son of Cosicas," where Cosicas is for Kheziga.[30]Cybernis went to the bottom of the Straits of Salamis with the entire Lycian fleet in theBattle of Salamis,but he may be commemorated by theHarpy Tomb.According to this theory, Cybernis was the KUB of the first coin legends, dated to the window, 520–500.[33]The date would have been more towards 500.[34]

There is a gap, however, between him and Kuprlli, who should have had a father named the same as his son, Kheziga. The name Kubernis does not appear again. Keen suggests thatDarius Icreated the kingship on reorganizing the satrapies in 525, and that on the intestate death of Kubernis in battle, the Persians chose another relative named Kheziga, who was the father of Kuprlli. The Lycian dynasty may therefore be summarized as follows:[35]

| Greek Name | Lycian "Kings" (at Xanthos) | Local Lycian rulers | Coinage | Status | Date BC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-dynastic period (c.540–c.530 BC) | Initial Achaemenid control since circa 542/539 BC.[36] | c.540–c.530 | |||

| Kosikas | Kheziga I | First of the line. | c.525 | ||

| Kubernis | KUB |  |

Second in succession, son of the former. | c.520–480 | |

| Kosikas | Kheziga II | Third in succession, unknown relative (possibly son of Kheziga I?). | fl. c.500 | ||

| ? | Kuprlli(ΚΟ𐊓, pronounced "coupe" ) | Kuprlli, son of Kheziga II, was fourth in succession. First monarch identifiable through coin legends. | 480–c.440 | ||

| During Kuprlli's long reign at least a dozen local Lycian rulers started to mint their own coins,[37]among themTeththiweibi: | |||||

| Teththiweibi | c.450–430/20 | ||||

| Kosikas | (Kheziga III: heir-apparent) | Son of Kuprlli, first in line to succeed him, but died young. | † c.460 | ||

| Harpagus (Iranian name) | (Arppakhu: regent for Kuprlli) | Son-in-law of Kuprlli. The elderly Kuprlli, when he became incapacitated, remained nominal king, but real power rested with Arpakkhu as his regent.[38] | fl. c.450 | ||

| Gergis | Kheriga | Fifth in succession, son of Arppakhu. Probably regent for Kuprlli in his last years, after his death Kheriga became king himself. | c.440-c.410 | ||

| ? | Kherei | Sixth in succession, brother of Kheriga. | c.410–c.390 | ||

| Arbinas(Iranian name) | Erbbina | Seventh in succession, son of Kheriga. The last known of the line. | c.390–c.380 | ||

| Artembares (Iranian name, *Rtambura, self-identified as "the Mede." ) | Arttum̃para | Ruler of western Lycia from Telmessos. Ousted by Perikle. | c.380–c.360 | ||

| Mithrapata | Mithrapata | Ruler in eastern Lycia. | c.390–c.370 | ||

| Pericles (Greek name) | Perikle | At first ruler of eastern Lycia from Limyra, then victor over Arttum̃para, rebel in theRevolt of the Satraps,last Lycian king. | c.360 | ||

Classical period[edit]

Ally of Athens in the Delian League (c. 470–430 BC)[edit]

Following the Achaemenid defeat in theGreco-Persian War(479 BC), the Lycians may have temporarily joined the Greek side during the counter-attacks of the SpartanPausaniasin the Eastern Mediterranean circa 478 BC.[39]However, the Lycian were still on the Persian side during the expeditions ofKimoncirca 470 BC, who finally persuaded the Lycian to join the Athenian alliance, theDelian League:Diodorusrelates that Kimon "persuaded those of Lycia and took them into his allegiance".[39]

As the power of Athens weakened and Athens and Sparta fought thePeloponnesian wars(431–404 BC), the majority of Lycian cities defaulted from theDelian League,with the exception of Telmessos and Phaselis. In 429 BC, Athens sent an expedition against Lycia to try to force it to rejoin the League. This failed when Lycia's leader Gergis/Kherigaof Xanthos defeated Athenian General Melesander.[40][41]

Renewed Achaemenid control (c. 430–333 BC)[edit]

The Lycians once again fell under Persian domination, and by 412 BC, Lycia is documented as fighting on the winning side of Persia. The Persiansatrapswere re-installed, but (as the coinage of the time attests) they allowed local dynasts the freedom to rule.[43]

The last known dynast of Lycia wasPerikles.He ruled 380–360 BC over eastern Lycia fromLimyra,at a time when Western Lycia was directly under Persian domination.[44]Pericles took an active part in theRevolt of the Satrapsagainst Achaemenid power, but lost his territory when defeated.[44][45][46]

After Perikles, Persian rule was reestablished firmly in Lycia in 366 or 362 BC. Control was taken byMausolus,the satrap of nearbyCaria,who moved the satrap's residence toHalicarnassus.[44]Lycia was also ruled directly by the Carian dynastPixodarus,son ofHecatomnus,as shown in theXanthos trilingual inscription.

Lycia was also ruled by men such asMithrapata(late 4th century BC), whose name was Persian. Persia held Lycia until it was conquered byAlexander III (the Great)of Macedonduring 334–333 BC.[47]

During the Alexander the Great period,Nearchuswas appointed viceroy of Lycia and of the land adjacent to it as far as mount Taurus.[48]

- Dynastic portraiture on coinage

Although many of the firstcoinsinAntiquityillustrated the images of various gods, the first portraiture of actual rulers appears with the coinage of Lycia in the late 5th century BC.[49][50]No ruler had dared to illustrate his own portrait on coinage until that time.[50]The Achaemenids had been the first to illustrate the person of their king or a hero in a stereotypical undifferentiated manner, showing a bust or the full body, but never an actual portrait, on theirSigloiandDariccoinage from circa 500 BC.[50][51][52]From the time ofAlexander the Great,portraiture of the issuing ruler would then become a standard, generalized, feature of coinage.[50]

-

Coin of the dynast of Lycia,Kherei,withAthenaon the obverse, and himself wearing thePersian capon the reverse. 410–390 BC.

-

DynastArbinas,in Persian dress, receiving emissaries. Scene from the upper podium frieze of theNereid Monument,c. 380 BC.

-

Portrait of Lycian rulerMithrapata(ruled 390–370 BC).

-

Coin ofPerikles,last king of Lycia. Circa 380–360 BC.

-

"Lycian sarcophagus of Sidon",Sidon,end of 5th century BC.

Hellenistic period (333–168 BC)[edit]

After thedeath of Alexander the Greatin 323 BC,his generalsfought amongst themselves over the succession. Lycia fell into the hands of the generalAntigonusby 304 BC. In 301 BC Antigonus was killed by an alliance of the other successors of Alexander, and Lycia became a part of the kingdom ofLysimachus,who ruled until he was killed in battle in 281 BC.[53]

Control then passed to the Ptolemaic Kingdom, centre on Egypt.Ptolemy II Philadelphos(ruled 285–246 BC), who supported the Limyrans of Lycia when they were threatened by theGalatians(a Celtic tribe that had invadedAsia Minor). The citizens of Limyra in return dedicated a monument to Ptolemy, called thePtolemaioncirca 270 BC.[54]By 240 BC Lycia was firmly part of thePtolemaic Kingdom,centred on Egypt,[55]and remained in their control through 200 BC.[56]

It had apparently come underSeleucidcontrol by 190 BC, when the Seleucids' defeat in theBattle of Magnesiaresulted in Lycia being awarded toRhodesin thePeace of Apameain 188 BC.

In 181 BC, at the end of theRoman-Seleucid War,the consulGnaeus Manlius Vulsodecided to fight theGalatian War(189 BC) against theGalatians.He was supported byAttalus II,the king ofPergamon.The two leaders marched inland and reached Pamphylia levying soldiers from local rulers. They then got to the territory of Cibyra, ruled by another tyrant called Moagetes. When Roman envoys went to the city he begged them not to ravage his lands as he was a friend of Rome and promised a paltry sum of money, fifteen talents. Moagetes sent his envoys to Manlius' camp. Polybius had Manlius say that he was the worst enemy of Rome and that he deserved punishment rather than friendship. Moagetes and his friends went to meet Manlius dressed in humble clothing, bewailing the weakness of his town and begging to accept the fifteen talents. Manlius was 'amazed at his impudence' and said that if he did not pay 500 talents, he would lay his lands to waste and sack the city. Moagetes successfully persuaded him to reduce the sum to 100 talents and promised an amount of grain, and Manlius moved on. Polybius described Moagetes as "cruel and treacherous man and worthy of more than a passing notice."[57]

Lycian League[edit]

| City | Votes |

|---|---|

| Xanthos | 3 |

| Patara | 3 |

| Myra | 3 |

| Pinara | 3 |

| Tlos | 3 |

| Olympos | 3 |

| Sympolity ofAperlae,Simena, Isinda,Apollonia |

1 |

| Amelas | ? |

| Antiphellus | ? |

| Arycanda | ? |

| Balbura | ? |

| Bubon | ? |

| Cyaneae | ? |

| Dias | ? |

| Gagae | ? |

| Idebessos | ? |

| Limyra | ? |

| Oenoanda | ? |

| Phaselis | ? |

| Phellus | ? |

| Podalia | ? |

| Rhodiapolis | ? |

| Sidyma | ? |

| Telmessus | ? |

| Trebenna | ? |

The Lycian league of independent city-states was the first such democratic union in history and the league remained strong in spite of the mountainous terrain, invasions of foreign powers and attempts of tyrants to take power.

Formation[edit]

The Lycian League (Lykiakon systemain Strabo's Greek transliterated, a "standing together" ) is first known from two inscriptions of the early 2nd century BC in which it honors two citizens.[58]Bryce hypothesizes that it was formed as an agent to convince Rome to rescind the annexation of Lycia toRhodes.It is not known for certain whether it was formed before or after Lycia was removed from Rhodian control. According toLivy,the consulLucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticusput Lycia under Rhodian control in 190 BC. He wrote that a Lycian embassy complained about the cruel tyranny of the Rhodians and that when they were under kingAntiochus III the Greatthey had been in liberty in comparison. It was slavery, rather that just political oppression: "they, their wives and children were the victims of violence; their oppressors vented their rage on their persons and their backs, their good name was besmirched and dishonoured, their condition rendered detestable in order that their tyrants might openly assert a legal right over them and reduce them to the status of slaves bought with money.. the senate gave them a letter to and to the Rhodians that...it was not the pleasure of the senate that either the Lycians or any other men born free should be handed over as slaves to the Rhodians or any one else. The Lycians possessed the same rights under the suzerainty and protection of Rhodes that friendly states possessed under the suzerainty of Rome."[59]

Polybiuswrote that the Romans sent envoys to Rhodes to say that "the Lycians had not been handed over to Rhodes as a gift, but to be treated like friends and allies."[60]The Rhodians claimed that king Eumenes of Pergamon had stirred up the Lycians against them.[61]In 169 BC, during the Third Macedonian War, the relationship between Rome and Rhodes became strained and the Roman senate issued a decree which gave the Carians and the Lycians their freedom.[62]Polybius recorded a decree “freeing” the Carians and Lycians in 168–7 BC.[63]

Strabo wrote that there were twenty-three cities which came together for a general assembly and had a share in its votes "after choosing whatever city they approve of". The last statement is unclear. The largest cities had three votes, the medium-sized ones two, and the rest one. He noted that the League did not have freedom over matters of war and peace: "Formerly they deliberated about war and peace, and alliances, but this is not now permitted, as these things are under the control of the Romans. It is only done by their consent, or when it may be for their own advantage." However, they had the freedom to choose aLyciarchas the head of the league and to designate general courts. He also noted "since they lived under such a good government, they remained ever free under the Romans, thus retaining their ancestral usages [i.e ancestral laws and customs]."[64]

Composition[edit]

Strabo wrote that according to a source the six largest wereXanthos,Patara,Pinara,Olympos,Myra,andTlos.Tlos was near the pass that leads over into Cibyra.[64]The names of the other cities has been identified by a study of the coins and mention in other texts.[65]The coins recognize two districts, termed, for want of a better term, "monetary districts:" Masicytus and Cragus, both named after mountain ranges, in the shadow of which, presumably, the communities lived and conducted business.[66]Where coinage before the Lycian League had often been stamped LY for Lycia, it was now stamped KP (kr) or MA.

In 81 BCLucius Licinius Murena,the Roman commander who fought theSecond Mithridatic War(83–81 BC) in Anatolia deposed Moagetes, a tyrant of the tetrapolis (four towns) in the Cibyratis (northern Lycia). It had been formed by the city ofCibyra Megale,(Greater Cibyra, as opposed toCibyra Mikra,Little Cibyra, of the coast, not too far from modernSide). It was in the Cibyratis region, in today'sTurkish Lake Region.According to Strabo, Cibyra had two votes, while the other three cities had one and the tetrarchy was ruled by a benign tyrant. When Murena ended the tyranny he included the cities ofBalburaandBubonwithin the territory of the Lycians.[67][68]

Roman period[edit]

Lycia was granted autonomy as a protectorate ofRomein 168 BC and remained so until becoming a Roman province in 43 AD under Claudius.[69]

When Rome got involved in the eastern Mediterranean the Lycians allied with Rome. An inscription found in Tyberissos provides the first record of such an alliance treaty (foedus). The dating is uncertain. It precedes the treaty of 46 BC (see below) and could go back to the second or first century BC. The context in which this treaty was made in unknown. It could have been concluded during the expansionist moves byAntiochus III the Great,the Seleucid king, in Anatolia prior to theRoman-Seleucid War(192–188 BC), or during or after this war. Alternatively, it could have been concluded in the context of theMithridatic Warsin Anatolia in the first century BC. The preamble stated: "There will be peace and loyal alliance between the People of the Romans and the cities of Lycia and the assembly of the Lycians by land and sea for all time.” There were four clauses which stipulated that: 1) the Lycian League was not to allow enemies of Rome to cross all territory over which they had authority so that they could bring war on Rome or her subjects and was not to give them aid; 2) Rome was not to allow enemies of the Lycians to pass through territory they controlled or had authority over so that they might bring war on the Lycian League or the people subject to them and was not to give them aid; 3) if anyone started a war against the Lycian people first, Rome was to come to her aid as soon as possible and if anyone started a war against Rome, the Lycian league was to aid Rome as soon as possible provided that this was allowed to Rome and the Lycian League in accordance with the agreements and oath; 4) Additions and subtractions to the agreements were possible if each side agreed though a joint decision.[70]

An inscription found on a statue-base found in Thespiae attests that in 46 BC Julius Caesar signed a treaty with the Lycian league. It had nine articles. The first article stipulated "Friendship, alliance and peace both by land and sea in perpetuity" Let the Lycians observe the power and preeminence of the Romans as is proper in all circumstances. "The other articles stipulated: 2) Neutrality of each party to the other's enemy; 3) mutual help in case of an attack on either party; 4) anyone charged with import or export of contraband goods was to be charged by the highest official of the two parties; 5) Romans accused of a capital crime in Lycia were to be judged in Rome by her own laws and Lycians accused of these crimes were to be judged in Lycia by her own laws; 6) Romans in a dispute with Lycians were to be judged in Lycia according to her own laws, if Lycians were brought to court by Romans the case was to be heard by whatever official the disputants chose for the case to be dealt with justly; 7) No person was to be taken as a surety, Roman and Lycian war prisoners were to be returned to their own countries, captured horses, slaves or ships were to be restored; 8) named cities, ports and territories which were restored to the Lycians were to belong to them; 9) both parties agreed to abide by the terms of this oath and the treaty. Details could be amended if both parties agreed.[71]

In 43 AD the emperorClaudiusannexed Lycia.Cassius Diowrote that Claudius ‘reduced the Lycians to servitude because they had revolted and slain some Romans and he incorporated them in the prefecture of Pamphylia. "He also provided some details of the investigation of this affair conducted in the senate.[72]Suetoniuswrote that Claudius "deprived the Lycians of their independence because of deadly intestine feuds."[73]In an inscription found atPergewhich has been dated to late 46/early 45 BC the Lycians, who described themselves as 'faithful allies’, praised Claudius for freeing them from disturbances, lawlessness and brigandage and for the restoration of the ancestral laws. It makes a reference to the transfer of power from the multitude to the councillors, selected from among the best. Therefore, it seems that there might have been a revolutionary popular uprising which could have overturned the established order. The annexation of Lycia seems to fit the common reason for anne xing Roman client states or allies in this period: the loss on stability due to internal strife or, in some cases, the weakening or end of a ruling dynasty. The restoration of ancestral law was probably linked to the Roman practice of respecting and guaranteeing the ancestral laws, customs and privileges of city-states or leagues of city-states it made alliance agreements with in the eastern Mediterranean. Lycia was annexed, but the Lycian League was retained as so were self-governance regarding most local matters according to local traditional laws and the League's authority over local courts. The treaty concluded by Caesar in 46 BC had already established a framework for the distinction of judicial areas under the competence of the Lycian League and those under the Roman praetor peregrino (chief justice for foreigners) and could be used to define the assignment of legal areas between the Roman provincial governor and the League. The Romans re-established stability in Lycia and retained friendly relations with the Lycians and Lycian rights to their traditional laws, customs and privileges.[74]

In 74 AD the emperorVespasianjoined the Roman provinces of Lycia andPamphyliainto the province ofLycia et Pamphylia.[75][76]Cassius Dio's statement that Claudius incorporated Lycia into Phampylia (which he had as governed by a prefect, rather than apropraetor,see above) is refuted by the existence of legati Augusti pro praetore Lyciae (imperial provincial governors of Lycia with propraetorial rank). The adoptive son and heir ofAugustus,Gaius Caesar,died in Lycia in 4 AD after being wounded during a campaign in Artagira, Armenia.[77]

Byzantine era[edit]

During the Byzantine period Lycia and Pamphylia came under the command of theKarabisianoi(the mainstay of the Byzantine navy from the mid-7th century until the early 8th century). After the Karabisianoi were disbanded (between c. 719/720 and c. 727) they became theTheme of the Cibyrrhaeots.

Turkish era[edit]

Lycia was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire and eventually became part ofTurkey.AfterWorld War I,Lycia was assigned to thekingdom of Italyaccording to the terms of theTreaty of Sèvresandoccupied for a few years,but in 1923 was assigned to Turkey.[78]

During this period, Lycia hosted both Turkish and Greek communities. The substantialChristiancommunity ofGreekslived in Lycia until the 1920s, when they were forced to migrate toGreeceafter thepopulation exchange between Greece and Turkeyfollowing theGreco-Turkish War (1919–1922).[79]The abandoned Greek villages in the region are a striking reminder of this exodus. Abandoned Greek houses can still be seen in the region, andKayais a Greekghost town.[79]A small population of Turkish farmers moved into the region when the Lycian Greeks migrated.[79]The region is now one of the key centres of domestic and foreign tourism in Turkey.

In Greek mythology[edit]

According toHerodotus,the earliest known name for the area wasMilyas,and its original inhabitants, who spoke theMilyan language,were theMilyae(Μιλύαι),[80]or Milyans, also known by theexonymsSólymoi(Σόλυμοι), Solymi, and Solymians.

InGreek mythology,SolymusorSolymoswas the ancestral hero andeponymof the Solymi. He was a son of eitherZeusorAres;his mother's name is variously given asChaldene,Caldene ( "daughter ofPisidus"), Calchedonia, or Chalcea" thenymph".[81][82][83][84]Meanwhile,Europahad (at least) two sons,SarpedonandMinos,who vied for the kingship of their native land,Crete.Minos drove Sarpedon and his people, theTermilae,into exile and they settled in Milyas. Subsequently,LycusofAthens(son ofPandion II), who was driven into exile by his brother, KingAegeus,settled in Milyas among the Termilae. The name Lycia was adopted subsequently in honor of Lycus. (It had in fact been around much longer under the nameLukka,probably derived from the same root asLatinlucus(grove, bright space)). Herodotus ends his tale with the observation that the Lycians werematrilineal.[85]

Lycia appears elsewhere in Greek myth, such as in the story ofBellerophon,who eventually succeeded to the throne of the Lycian kingIobates(or Amphianax). Lycia was frequently mentioned byHomeras an ally ofTroy.In Homer'sIliad,the Lycian contingent was said to have been led by two esteemed warriors:Sarpedon(son ofZeusandLaodamia) andGlaucus(son ofHippolochus).

See also[edit]

- Ancient regions of Anatolia

- Lycian peasants

- Lycian script

- SaintGerasimus of the Jordan,5th-century Christian saint born in Lycia

- Saint Nicholas,Christian saint said to have been born in Patara, Lycia

- Saint Christopher,Christian saint said to have been of the region of Lycia

References[edit]

- ^Bernstein, Richard (19 September 2005)."A Congress, Buried in Turkey's Sand".The New York Times.Archived fromthe originalon 5 September 2012.

- ^Keen 1998,p.130.

- ^Harrison, Martin; Young, Wendy (2001).Mountain and plain: from the Lycian coast to the Phrygian plateau in the late Roman and early Byzantine period.Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 48–50.

- ^"Tahtali Dagi (2366 m.)".Antalya Website.antalyaonline.net. 1996–2011. Archived fromthe originalon 25 August 2012.Retrieved21 March2012.

- ^Jacobson, Matthew J.; Pickett, Jordan; Gascoigne, Alison L.; Fleitmann, Dominik; Elton, Hugh (27 June 2022)."Settlement, environment, and climate change in SW Anatolia: Dynamics of regional variation and the end of Antiquity".PLOS ONE.17(6): e0270295.Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1770295J.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0270295.ISSN1932-6203.PMC9236232.PMID35759500.

- ^"Xanthos-Letoon".World Heritage – The List.UNESCO.Retrieved13 October2010.

- ^Schürr, Diether."Der lykische Dynast Arttumbara und seine Anhänger".Akademie Verlag.Retrieved7 April2021.=Klio94/1 (2012) 18-44.

- ^The Payava Tomb.

- ^Keen 1998,p. 11.

- ^Fant, Clyde E.; Reddish, Mitchell G. (2003).A Guide to Biblical Sites in Greece and Turkey.Oxford University Press. p. 485.ISBN9780199881451.

- ^Keen 1998,p. 49.

- ^Trevor Bryce(2005)The Kingdom of the Hittites,p. 54

- ^Ilya Yakubovich (2010)Sociolinguistics of the Luvian Language,Leiden: Brill, p. 134

- ^Bryce, Trevor (2005).The Trojans and their Neighbours.Taylor & Francis. pp. 81–82.ISBN978-0-415-34959-8.

- ^Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric (2012).The Ahhiyawa Texts.Brill. p. 99.ISBN978-1589832688.

- ^Bryce, Trevor (2005).The Trojans and their Neighbours.Taylor & Francis. pp. 82, 148–149.ISBN978-0-415-34959-8.

- ^Bryce 2005, p. 336; Yakubovich 2010, p. 134

- ^Keen 1998,p. 73.

- ^Histories,Book I, Section 176.

- ^abKeen 1998,p. 76.

- ^Keen 1998,pp. 78, 116–117.

- ^Herodotus, The Histories, 3.90

- ^abKeen 1998,p. 84.

- ^André-Salvini, Béatrice (2005).Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia.University of California Press. p. 46.ISBN9780520247314.

- ^Keen 1998,p. 86.

- ^Ching, Francis D.K;Jarzombek, Mark M.;Prakash, Vikramaditya (2017).A Global History of Architecture.John Wiley & Sons. p. 707.ISBN9781118981603.

- ^Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. (1972).History of Indian and Indonesian art.p.12.

- ^Bombay, Asiatic Society of (1974).Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay.Asiatic Society of Bombay. p. 61.

- ^Joveau-Dubreuil, Gabriel (1976).Vedic antiquites.Akshara. p. 4.

The Lydian tombs at Pinara and Xanthos, on the south-coast of Asia Minor, were excavated like the early Indian rock-hewn chaitya-hall.

- ^abKeen 1998,p. 87.

- ^Keen 1998,p. 81.

- ^Herodotus, The Histories, 7.98.

- ^Keen 1998,p. 89.

- ^Hill 1897,p. xxvi. – Coin Series I of the British Museum, bearing the KUB, is dated by Hill to the window 520–480, somewhat less precisely than the 520–500.

- ^Keen 1998,p. 221.

- ^Keen 1998,p. 224.

- ^Keen 1998,pp. 113–114.

- ^Keen 1998,p. 117.

- ^abKeen 1998,p.97–

- ^The History of the Peloponnesian War: Translated from the Greek of Thucydides. To which are Annexed, Three Preliminary Discourses. I. On the Life of Thucydides. II. On His Qualifications as a Historian. III. A Survey of the History.Edward Earle T.H. Palmer, printer. 1818. p. 173.

- ^Tuplin, Christopher (2007).Persian Responses: Political and Cultural Interaction with(in) the Achaemenid Empire.ISD LLC. p. 150.ISBN9781910589465.

- ^Mortensen, Eva; Poulsen, Birte (2017).Cityscapes and Monuments of Western Asia Minor: Memories and Identities.Oxbow Books. p. 273.ISBN9781785708398.

- ^"Lycian Dynasts".AsiaMinorCoins.

- ^abcHouwink ten Cate, Philo Hendrik Jan (1961).The Luwian Population Groups of Lycia and Cilicia Aspera During the Hellenistic Period.Brill Archive. pp. 12–13.

- ^Briant, Pierre (2002).From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire.Eisenbrauns. p. 673.ISBN9781575061207.

- ^Bryce, Trevor (2009).The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire.Routledge. p. 419.ISBN9781134159079.

- ^Haywood, John; et al. (2002).Historical Atlas of the Classical World: 500 BC – AD 600.New York: Barnes & Noble Books. Plate 2.09.

- ^"Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, 3.6".

- ^Carradice, Ian (1978).Ancient Greek Portrait Coins.British Museum Publications. p. 2.ISBN9780714108490.

The earliest attempts at portraiture appear to have taken place in Lycia. The heads of various dynasts appear on coins of the fifth century.

- ^abcdWest, Shearer; Birmingham, Shearer (2004).Portraiture.OUP Oxford. p. 68.ISBN9780192842589.

- ^Root, Margaret Cool (1989)."The Persian archer at Persepolis: aspects of chronology, style and symbolism".Revue des Études Anciennes.91:43–50.doi:10.3406/rea.1989.4361.

- ^"Half-figure of the King: unravelling the mysteries of the earliest Sigloi of Darius I"(PDF).The Celator.26(2): 20. February 2012.Archived(PDF)from the original on 21 November 2018.

- ^Haywood 2002,p.[page needed].

- ^Waelkens, Marc; Loots, Lieven (2000).Sagalassos Five.Leuven University Press. p. 497.ISBN9789058670793.

- ^Barraclough, Geoffrey, ed. (2003).Collins Atlas of World History.Ann Arbor, Michigan: Borders Press. p. 77.

- ^Black, Jeremy, ed. (2000).World History Atlas.London: Dorling Kindersley. p. 179.

- ^"Polybius, The histories, 21.34".

- ^Bryce & Zahle 1986,p. 102.

- ^"Livy, The History of Rome, 41.6.8–12".

- ^"Polybius, The Histories, 25.3".

- ^"Livy, The History of Rome, 42.14.8".

- ^"Livy, The History of Rome, 44.15.1".

- ^"Polybius, The Histories, 30.5.12".

- ^ab"Strabo, Geographia, 14.3.3".

- ^"Lycian League cities and coins".AsiaMinorCoins.

- ^Hill 1897,p. xxii.

- ^"Strabo Geographia, 13.4.17".

- ^Hill 1897,p. xxiii.

- ^Barraclough 2003,p.[page needed].

- ^Derow, Peter; Christopher John Smith; Liv Mariah Yarrow (2012).Imperialism, cultural politics, and polybius.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 136.

- ^"Roman-Lycian Friendship and Reciprocal Military Alliance 46 AD".Lycian Turkey - Discover the Beauty of Ancient Lycia.Archived fromthe originalon 24 September 2015.Retrieved12 July2016.– Note that the given date is mistaken. It should be 46 BC instead of 46 AD

- ^Cassius Dio, Roman History, 60.17.3–4

- ^Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars; The Life of Claudius, 23.3

- ^Kantor, Georgy (2006).Ancestral laws under the Roman rule: The case of Lycia(PhD). Balliol College, University of Oxford.

- ^Şahin, S. and M. Adak,Stadiasmus Patarensis. Itinera Romana Provinciae Lyciae.İstanbul 2007; F. Onur, Two Procuratorian Inscriptions from Perge,Gephyra5 (2008), 53–66.

- ^Syme R., Pamphylia from Augustus to Vespasian, ibid., XXX, 1937, pp. 227–231

- ^Mommsen, Theodore, A History of Rome Under the Emperors, p. 107

- ^"Treaty of Sevres".10 August 2015.

- ^abcDarke, Diana (1986).Guide to Aegean and Mediterranean Turkey.M. Haag. p.160.ISBN9780902743342.

The Lycians were essentially Greeks so they were moved to Greece, leaving a small population of Turkish farmers to move in behind them. The Greek ghost town of Kaya in the hills behind Fethiye is the most dramatic reminder of this exodus, but derelict Greek houses can also be seen at Kalkan, Kas and Demre.

- ^Herod. vii. 77; Strab. xiv. p. 667; Plin. v. 25, 42.

- ^Stephanus of Byzantium,s. v.Pisidia

- ^Etymologicum Magnum,721. 43, underSolymoi

- ^AntimachusinscholiaonHomer,Odyssey,5. 283

- ^Clement of RomeinRufinus of Aquileia,Recognitiones,10. 21

- ^Herodotus, The Histories, 1.173.

Sources[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

- "Poem on the Battle of Kadesh" 305–313, Ramesses II

- "Great Karnak Inscription" 572–592, Merneptah

- Breasted, J. H. 1906.Ancient Records of Egypt. Vol. III.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- "Plague Prayers of Mursilis" A1–11, b, Mursilis

- Pritchard, J. B. 1969.Ancient Near Eastern Texts.Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ovidius Naso, Publius(1997).Ovid's Metamorphoses, Books 1-5.University of Oklahoma Press.ISBN978-0806128948.

Secondary sources[edit]

- Auerbach, Jeffrey; Hoffenberg, Peter (2013).Britain, the Empire, and the World at the Great Exhibition of 1851.Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.ISBN978-1409480082.

- Bryce, T.; Zahle, J. (1986).The Lycians.Vol. 1. Copenhagen:Museum Tusculanum Press.– Covers the Lycians and where they lived, their history, language, culture, cults, and their language.

- Hill, George Francis (1897)."Catalogue of the Greek Coins of Lycia, Pamphylia, and Pisidia".A Catalogue of the Greek Coins in the British Museum.London: Trustees of the British Museum.– A presentation of the history of Lycia during the time of its minting coins, and the coins.

- Keen, Antony G. (1998) [1992].Dynastic Lycia: A Political History of the Lycians & Their Relations with Foreign Powers, c. 545 – 362 BC.Mnemosyne: bibliotheca classica Batavia. Supplementum. Leiden; Boston; Köln: Brill.ISBN9004109560.

- Spratt, Thomas(1847).Travels in Lycia, Milyas, and the Cibyratis.London: J. Van Voorst.OCLC582161294.

Further reading[edit]

- Barnett, R. D. (1975). "The Sea Peoples". InJ. B. Bury;S. A. Cook; F. E. Adcock (eds.).The Cambridge Ancient History.Vol. II, part 2. Cambridge:Cambridge University Pressbarne.pp. 362–366.– Refers to many differentsea peoplesand their contact withEgyptandAnatolia.Also tells about thePhilistinesduring the reign ofRamesses III.

- Bryce, T.(1993). "Lukka Revisited".Journal of Near Eastern Studies.51(2): 121–130.doi:10.1086/373535.S2CID222441745.– Discusses Lukka's relations to other regions (likeMiletus) and where they inhabited.

- Drews, R.(1995).The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C.Princeton:Princeton University Press.– A description of the Egyptian evidence on the Sea Peoples.

- Jacobson MJ, Pickett J, Gascoigne AL,FleitmannD, Elton H (2022) Settlement, environment, and climate change in SW Anatolia: Dynamics of regional variation and the end of Antiquity. PLoS ONE 17(6): e0270295.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270295

- Kılıç Aslan, Selen (2023).Lycian families in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. A regional study of inscriptions: towards a social and legal framework.Leiden; Boston: Brill.ISBN9789004548411.

External links[edit]

- Satyurek, Patty; Satyurek, Kemal."Lycian Turkey".lycianturkey. Archived fromthe originalon 4 February 2012.Retrieved14 February2012.

- Walker, Christopher; Anderson, Thorne (Photographer) (September–October 2007)."Splendid Ruins for an 'Excellent Republic'".Saudi Aramco World.

- Foss, Pedar W."Lycia".Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces (ERP).Archived fromthe originalon 26 February 2012.

- "Virtual Tours / Myra, Mahmutlar, Lara (Turkey)".EDS Systems.Fullscreen panoramas of the rock-cut tombs of the ancient Lycian necropolis at Myra

- "Virtual Tour—Demre. Myra (Lycia)".Alexander Peskov Photography. 2011.

- Clow, Kate."Lycian Way guidebook".Retrieved3 May2017.

- Map of the Roman state according to the Compilation notitia dignitatum

- Lycia

- Ancient Greek geography

- Late Roman provinces

- Buildings and structures in Antalya Province

- Historical regions of Anatolia

- Muğla Province

- Rock-cut tombs

- Praetorian prefecture of the East

- Geography of Antalya Province

- Tourist attractions in Antalya Province

- States and territories established in the 15th century BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 14th century BC

- States and territories established in the 13th century BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 6th century BC

- Lycia et Pamphylia