Macrauchenia

| Macrauchenia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype skeleton ofM. patachonica(larger) andPhenacodusprimaevus(smaller) atAmerican Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Litopterna |

| Family: | †Macraucheniidae |

| Subfamily: | †Macraucheniinae |

| Genus: | †Macrauchenia Owen,1838 |

| Type species | |

| †Macrauchenia patachonica Owen, 1838

| |

| |

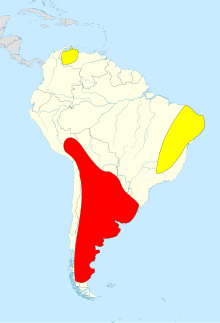

| Map showing the distribution ofMacraucheniain red, andXenorhinotheriumin yellow, inferred from fossil finds | |

Macrauchenia( "longllama",based on the now-invalid llama genus,Auchenia,from Greek "big neck" ) is an extinct genus of largeungulatenative to South America from the latePlioceneto the end of thePleistocene.[1]It is a member of the extinct orderLitopterna,a group ofSouth American native ungulatesdistinct from the two orders which contain all living ungulates which had been present in South America since the earlyCenozoic,over 60 million years ago, prior to the arrival of living ungulates in South America around 2.5 million years ago as part of theGreat American Interchange.[2]The bodyform ofMacraucheniahas been described as similar to a camel,[3]being one of the largest-known litopterns, with an estimated body mass of around 1 tonne.[2]The genus gives its name to its family,Macraucheniidae,which likeMacraucheniatypically had long necks and three-toed feet, as well as a retracted nasal region,[1]which inMacraucheniamanifests as the nasal opening being on the top of the skull behind the eye sockets.[4]This has historically been argued to correspond to the presence of a tapir-likeproboscis,but some recent authors suggest a moose-like prehensile lip[5]or asaiga antelope-like nose to filter dust[6]are more likely.

Only one species is generally considered valid,[7]M. patachonica,which was described byRichard Owenbased on remains discovered byCharles Darwinduring thevoyage of theBeagle.[8]M. patachonicais primarily known from localities in thePampas,but is known from remains found across theSouthern Coneextending as far south as southernmostPatagonia,and as far northeast as Southern Peru. Another genus of macraucheniidXenorhinotheriumwas present in northeast Brazil and Venezuela during the Late Pleistocene.[4]

Macraucheniabecame extinct as part of theend-Pleistocene extinctionsaround 12,000 years ago, along with the vast majority of other large mammals native to the Americas.[2]

Taxonomy

[edit]

Macraucheniafossils were first collected on 9 February 1834 atPort St JulianinPatagonia(Argentina) byCharles Darwin,whenHMSBeaglewas surveying the port.[9]As a non-expert he tentatively identified the leg bones and fragments of spine he found as "some large animal, I fancy aMastodon".In 1837, soon after theBeagle'sreturn, the anatomistRichard Owenidentified the bones, including vertebrae from the back and neck, as from a gigantic creature resembling allamaorcamel,which Owen namedMacrauchenia patachonica.[10]In naming it, Owen noted the original Greek termsµακρος(makros,large or long) andαυχην(auchèn,neck), as used byIlligeras the basis ofAucheniaas a generic name for the llama,Vicugnaand so on.[11]The find was one of the discoveries leading to theinception of Darwin's theory.Since then, moreMacraucheniafossils have been found, mainly in Patagonia, but also inBolivia,ChileandVenezuela.

The related genusCramaucheniawas named byFlorentino Ameghinoas a deliberate anagram ofMacrauchenia.

Evolution

[edit]

It is likely thatMacraucheniaevolved from earlier litopternsTheosodon,CramaucheniaorPromacrauchenia,or a similar species.Litopternawas one of the five (four in some classifications) ancient orders of endemic South American mammals collectively calledmeridiungulates.Their relationships with other mammal groups outside South America have been poorly understood, as their early evolutionary history would have been in Western Gondwana, and outside of South America this area is now Antarctica. When South America separated from Antarctica in the Eocene,[12]meridungulate orders survived in South America in isolation. Most flourished in thePaleogeneand then diminished. Formerly, North American paleontologists considered them inferior to Northern Hemisphere taxa and to have been outcompeted to extinction in theGreat American Biotic Interchangeafter the establishment of theCentral Americanland bridge. However, more recent evidence shows that three of the meridungulate orders declined long before, just as happened to early mammal groups elsewhere.[13]Litopterns and notoungulates continued, evolving into a variety of more derived forms. While toxodontid notoungulates expanded into North America during the GABI, litopterns remained confined to South America.Macraucheniawas among the last surviving meridungulates, along with litopterns such asMacraucheniopsis,NeolicaphriumandXenorhinotheriumand the large notoungulatesPiauhytherium,Trigodonops,ToxodonandMixotoxodon.These lastendemic South American hoofed animalsdied out at the end of theLujanian(10,000–20,000 years ago).[14]

Sequencing ofmitochondrial DNAextracted from anM. patachonicafossil from a cave in southern Chile indicates thatMacrauchenia(and by inference, Litopterna) is thesister grouptoPerissodactyla,with an estimated divergence date of sixty-six million years ago.[15][16]Analysis of collagen sequences obtained fromMacraucheniaandToxodonreached a similar conclusion and extended membership in the sister group clade to notoungulates.[17][18]

Description

[edit]

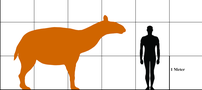

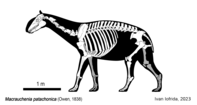

Macraucheniahad a somewhatcamel-like body, with sturdy legs, a long neck and a relatively small head. Its feet, however, more closely resembled those of a modernrhinoceros,with one central toe and two side toes on each foot. It was a large animal measuring around 2.5–3 metres (8.2–9.8 ft) long, 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) tall at the shoulder and weighing up to 909–1,000 kg (2,004–2,205 lb), about the size of a black rhinoceros.[19][20][21]

One striking characteristic ofMacraucheniais the openings for the nostrils on top of the head, above and between the eyes. Increasingly retracted nostrils are an evolutionary trend in later litopterns. Because mammals with trunks show the nostrils in a similar position, a popular hypothesis is thatMacraucheniahad a trunk similar to atapiror an inflated snout like that of thesaiga antelope,perhaps to keep dust out of the nostrils.[19]However, a 2018 study comparing the skulls of tapirs and various other herbivorous extant and extinct mammal species instead saw similarities with the skulls ofmoose,suggesting thatMacraucheniaand othermacraucheniids,such asHuayquerianadid not possess trunks.[22]However,pictographsdepicting various extinctmegafaunadated to around 12,600 to 11,800 years ago from theSerranía de La Lindosarock formationofGuaviare,Colombiashowed what appears to be a possible trunked macraucheniid, presumablyXenorhinotherium.[23][24]

The snout ofMacraucheniais completely enclosed by bone, and the animal has an elongated neck that allowed it to reach upward; no living mammal with a proboscis has these features. An alternative hypothesis is that these litopterns were high browsers on tough and thorny vegetation, and retracted nostrils allowed them to reach leaves without being impaled in the nose.SauropodSauropods(reconstructed as high browsers onconiferneedles andcycads) have similar snouts, and living giraffes andgerenuks,high browsers on thorny vegetation, have more retracted nostrils than related taxa with other feeding habits.[13]

One insight intoMacrauchenia'shabits is that its ankle joints and shin bones may indicate that it was adapted to have unusually good mobility, being able to rapidly change direction when it ran at high speed.[25]

Macraucheniais known, like its relativeTheosodon,to have had a full set of 44 teeth.[citation needed]

Paleobiology

[edit]

Macraucheniawas a herbivore, likely living on leaves from trees or grasses. Carbon isotope analysis ofM. patachonica'stooth enamel,as well as analysis of itshypsodontyindex (low in this case; i.e., it wasbrachydont), body size and relativemuzzlewidth suggests that it was a mixed feeder, combining browsing onC3foliage with grazing onC4grasses.[26]A dental microwear, occusal enamel, and carbon isotope analysis ofMacraucheniaandXenorhinotheriumfound that both were grazers on C3 grasses.[4]Evidence fromdental calculushas further confirmed the status ofM. patachonicaas a C3grazer.[27]

The genus was widespread, found in environments that ranged from dry to humid, from southern Chile to northeastern Brazil and the coast of Venezuela. Fossils ofM. ullomensishave been found in Bolivia at altitudes up to 4,000 metres. Habits and diet may have varied depending on the environment, but in plant feeders an elongated neck is usually an adaptation to allow high browsing on trees and shrubs. As the genus was not confined to forest, it was probably able to exploit more marginal environments by mi xing high browsing with low browsing and grazing. A site in northern Chile preserved the remains of five subadults associated together, which suggestsMacraucheniamay have lived in large herds or family groups.[13]

WhenMacraucheniafirst arose, it could have been preyed upon by the largest of native South American mammal predators, the sabertoothedsparassodontThylacosmilus.The largestphorusrhacidbirds may also have been able to prey on juveniles. After the GABI, the primary predator on adults would have been the very large sabertoothed catSmilodon populator[28]andgiant short-faced bears.Dire wolvesandjaguarsmay also have huntedMacrauchenia,particularly juveniles.

It is presumed thatMacraucheniadealt with its predators primarily by outrunning them, or, failing that, kicking them with its long, powerful legs. The large size of adults would have limited their vulnerability to most predators. Its potential ability to twist and turn at high speed could have enabled it to evade pursuers; bothThylacosmilusandS. populatorwere ambush hunters likely unable to run down prey over distance if the prey evaded the first attack.

Distribution

[edit]Fossils ofMacraucheniahave been found in:[29]

- Miocene

- Pliocene

- Pleistocene

References

[edit]- ^abPüschel, Hans P.; Alarcón-Muñoz, Jhonatan; Soto-Acuña, Sergio; Ugalde, Raúl; Shelley, Sarah L.;Brusatte, Stephen L.(June 2023)."Anatomy and phylogeny of a new small macraucheniid (Mammalia: Litopterna) from the Bahía Inglesa Formation (late Miocene), Atacama Region, Northern Chile".Journal of Mammalian Evolution.30(2): 415–460.doi:10.1007/s10914-022-09646-0.ISSN1064-7554.

- ^abcCroft, Darin A.; Gelfo, Javier N.; López, Guillermo M. (2020-05-30)."Splendid Innovation: The Extinct South American Native Ungulates".Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences.48(1): 259–290.Bibcode:2020AREPS..48..259C.doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-072619-060126.ISSN0084-6597.S2CID213737574.

- ^Defler, Thomas (2019),"The Native Ungulates of South America (Condylarthra and Meridiungulata)",History of Terrestrial Mammals in South America,Topics in Geobiology, vol. 42, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 89–115,doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98449-0_5,ISBN978-3-319-98448-3,S2CID91879648,retrieved2024-01-30

- ^abcde Oliveira, Karoliny; Araújo, Thaísa; Rotti, Alline; Mothé, Dimila; Rivals, Florent; Avilla, Leonardo S. (March 2020)."Fantastic beasts and what they ate: Revealing feeding habits and ecological niche of late Quaternary Macraucheniidae from South America".Quaternary Science Reviews.231:106178.Bibcode:2020QSRv..23106178D.doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106178.S2CID213795563.

- ^Moyano, Silvana Rocio; Giannini, Norberto Pedro (November 2018)."Cranial characters associated with the proboscis postnatal-development in Tapirus (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae) and comparisons with other extant and fossil hoofed mammals".Zoologischer Anzeiger.277:143–147.Bibcode:2018ZooAn.277..143M.doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2018.08.005.hdl:11336/86349.

- ^Blanco, R. Ernesto; Jones, Washington W.; Yorio, Lara; Rinderknecht, Andrés (October 2021)."Macrauchenia patachonica Owen, 1838: Limb bones morphology, locomotory biomechanics, and paleobiological inferences".Geobios.68:61–70.Bibcode:2021Geobi..68...61B.doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2021.04.006.

- ^Souza Lobo, Leonardo; Lessa, Gisele; Cartelle, Cástor; and Romano, Pedro S. R. (September 2017)."Dental eruption sequence and hypsodonty index of a Pleistocene macraucheniid from the Brazilian Intertropical Region".Journal of Paleontology.91(5): 1083–1090.Bibcode:2017JPal...91.1083S.doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.54.ISSN0022-3360.

- ^Fernicola, Juan C., Vizcaino, Sergio F., & De Iuliis, Gerardo (2009). The fossil mammals collected by Charles Darwin in South America during his travels on board the HMS Beagle.Revista De La Asociación Geológica Argentina,64(1), 147-159. Retrieved fromhttps://revista.geologica.org.ar/raga/article/view/1339

- ^Darwin, Charles (2001).Keynes, Richard D.(ed.).Charles Darwin's Beagle diary.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 214.ISBN9780521003179.Retrieved19 December2008.

- ^"Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 238 — Darwin, C. R. to Henslow, J. S., Mar 1834".Archived fromthe originalon 2009-01-16.Retrieved2008-12-19.

- ^Owen 1838,p. 35

- ^"Tectonic history: into the deep freeze".Discovering Antarctica.Retrieved2019-07-10.

- ^abcCroft, Darin (2016).Horned Armadillos and Rafting Monkeys; the Fascinating Fossil Mammals of South America.Indiana University Press.

- ^Alberto L. Cione, Eduardo P. Tonni, Leopoldo Soibelzon:The Broken Zig-Zag: Late Cenozoic large mammal and tortoise extinction in South America.In:Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales.5, 1, 2003,ISSN1514-5158,S. 1–19,onlineArchived2011-07-06 at theWayback Machine

- ^Westbury, M.; Baleka, S.; Barlow, A.; Hartmann, S.; Paijmans, J. L. A.; Kramarz, A.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Bond, M.; Gelfo, J. N.; Reguero, M. A.; López-Mendoza, P.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Rinderknecht, A.; Jones, W.; Mena, F.; Billet, G.; de Muizon, C.; Aguilar, J. L.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Hofreiter, M. (2017-06-27)."A mitogenomic timetree for Darwin's Enigma tic South American mammalMacrauchenia patachonica".Nature Communications.8:15951.Bibcode:2017NatCo...815951W.doi:10.1038/ncomms15951.PMC5490259.PMID28654082.

- ^Strickland, Ashley (27 June 2017)."DNA solves ancient animal riddle that Darwin couldn't".CNN.Retrieved19 July2024.

- ^Welker, Frido;Collins, Matthew J.;Thomas, Jessica A.; Wadsley, Marc; Brace, Selina; Cappellini, Enrico; Turvey, Samuel T.; Reguero, Marcelo; Gelfo, Javier N.; Kramarz, Alejandro; Burger, Joachim;Thomas-Oates, Jane;Ashford, David A.; Ashton, Peter; Rowsell, Kerry; Porter, Duncan M.;Kessler, Benedikt;Fischer, Roman; Baessmann, Carsten; Kaspar, Stephanie; Olsen, Jesper V.; Kiley, Patrick; Elliott, James A.; Kelstrup, Christian D.; Mullin, Victoria; Hofreiter, Michael;Willerslev, Eske;Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Orlando, Ludovic; Barnes, Ian & MacPhee, Ross D. E. (2015-03-18)."Ancient proteins resolve the evolutionary history of Darwin's South American ungulates".Nature.522(7554): 81–84.Bibcode:2015Natur.522...81W.doi:10.1038/nature14249.hdl:11336/14769.ISSN0028-0836.PMID25799987.S2CID4467386.

- ^Buckley, Michael (2015-04-01)."Ancient collagen reveals evolutionary history of the endemic South American 'ungulates'".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.282(1806): 20142671.doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2671.PMC4426609.PMID25833851.

- ^abPalmer, D., ed. (1999).The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals.London: Marshall Editions. p. 248.ISBN978-1-84028-152-1.

- ^Fariña RA, Czerwonogora A, di Giacomo M (March 2014)."Splendid oddness: revisiting the curious trophic relationships of South American Pleistocene mammals and their abundance".Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências.86(1): 311–31.doi:10.1590/0001-3765201420120010.PMID24676170.

- ^Cid, A.S.; Anjos, R.M.; Zamboni, C.B.; Cardoso, R.; Muniz, M.; Corona, A.; Valladares, D.L.; Kovacs, L.; Macario, K.; Perea, D.; Goso, C.; Velasco, H. (2014). "Na, K, Ca, Mg, and U-series in fossil bone and the proposal of a radial diffusion–adsorption model of uranium uptake".Journal of Environmental Radioactivity.136:131–139.Bibcode:2014JEnvR.136..131C.doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2014.05.018.hdl:11336/5799.PMID24953228.

- ^Moyano, Silvana Rocio; Giannini, Norberto Pedro (2018-10-10)."Cranial characters associated with the proboscis postnatal-development in Tapirus (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae) and comparisons with other extant and fossil hoofed mammals".Zoologischer Anzeiger.277(7554): 143–147.Bibcode:2018ZooAn.277..143M.doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2018.08.005.hdl:11336/86349.ISSN0044-5231.

- ^Morcote-Ríos, Gaspar; Aceituno, Francisco Javier; Iriarte, José; Robinson, Mark; Chaparro-Cárdenas, Jeison L. (2020-04-29)."Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa".Quaternary International.578:5–19.doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.04.026.ISSN1040-6182.S2CID219014558.

- ^"12,000-Year-Old Rock Drawings of Ice Age Megafauna Discovered in Colombian Amazon".Sci-News.3 December 2020.Retrieved2020-12-04.

- ^Fariña, Richard A.; Blanco, R. Ernesto; Christiansen, Per (2005)."Swerving as the escape strategy of Macrauchenia patachonica Owen (Mammalia; Litopterna)".Ameghiniana.42(4): 752–760.

- ^MacFadden, Bruce J.; Shockey, Bruce J. (Winter 1997). "Ancient feeding ecology and niche differentiation of Pleistocene mammalian herbivores from Tarija, Bolivia: morphological and isotopic evidence".Paleobiology.23(1): 77–100.Bibcode:1997Pbio...23...77M.doi:10.1017/S0094837300016651.JSTOR2401158.S2CID88948874.

- ^de Oliveira, Karoliny; Asevedo, Lidiane; Calegari, Marcia R.; Gelfo, Javier N.; Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo (August 2021)."From oral pathology to feeding ecology: The first dental calculus paleodiet study of a South American native megamammal".Journal of South American Earth Sciences.109:103281.Bibcode:2021JSAES.10903281D.doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103281.Retrieved25 April2024– via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^Antón, Mauricio."Sabertooth".Indiana University Press.Archived fromthe originalon 2015-06-05.Retrieved2019-07-10.

- ^MacraucheniaatFossilworks.org

Further reading

[edit]- Cox, Barry; Harrison, Colin; Savage, R.J.G.; Gardiner, Brian; Palmer, Douglas (1999) [1988]."South American Hoofed Mammals (Continued)".The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life.Simon & Schuster.p. 248.ISBN0-684-86411-8.

- Owen, Richard(1838)."Description of Parts of the Skeleton of Macrauchenia patachonica".In Darwin, C. R. (ed.).Fossil Mammalia Part 1 No. 1.The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. London: Smith Elder and Co.

- Parsons, Jayne (2001).Dinosaur Encyclopedia.DK.

External links

[edit]- Macraucheniids

- Messinian first appearances

- Holocene extinctions

- Miocene mammals of South America

- Pliocene mammals of South America

- Pleistocene mammals of South America

- Lujanian

- Ensenadan

- Uquian

- Chapadmalalan

- Montehermosan

- Huayquerian

- Neogene Argentina

- Cerro Azul Formation

- Pleistocene Argentina

- Pleistocene Bolivia

- Pleistocene Brazil

- Pleistocene Chile

- Pleistocene Paraguay

- Pleistocene Peru

- Dolores Formation, Uruguay

- Pleistocene Venezuela

- Fossils of Argentina

- Fossils of Bolivia

- Fossils of Brazil

- Fossils of Chile

- Fossils of Paraguay

- Fossils of Peru

- Fossils of Uruguay

- Fossils of Venezuela

- Fossil taxa described in 1838

- Taxa named by Richard Owen

- Prehistoric placental genera

- Sopas Formation