Macroeconomics

| Part ofa serieson |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

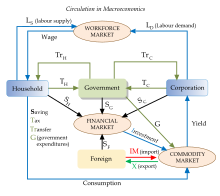

Macroeconomicsis a branch ofeconomicsthat deals with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of aneconomyas a whole.[1]This includes national, regional, andglobal economies.[2][3]Macroeconomists study topics such asoutput/GDP(gross domestic product) andnational income,unemployment(includingunemployment rates),price indicesandinflation,consumption,saving,investment,energy,international trade,andinternational finance.

Macroeconomics andmicroeconomicsare the two most general fields in economics.[4]The focus of macroeconomics is often on a country (or larger entities like the whole world) and how its markets interact to produce large-scale phenomena that economists refer to as aggregate variables. In microeconomics the focus of analysis is often a single market, such as whether changes in supply or demand are to blame for price increases in the oil and automotive sectors. From introductory classes in "principles of economics" through doctoral studies, the macro/micro divide is institutionalized in the field of economics. Most economists identify as either macro- or micro-economists.

Macroeconomics is traditionally divided into topics along different time frames: the analysis of short-term fluctuations over thebusiness cycle,the determination of structural levels of variables like inflation and unemployment in the medium (i.e. unaffected by short-term deviations) term, and the study of long-term economic growth. It also studies the consequences of policies targeted at mitigating fluctuations likefiscalormonetary policy,using taxation and government expenditure or interest rates, respectively, and of policies that can affect living standards in the long term, e.g. by affecting growth rates.

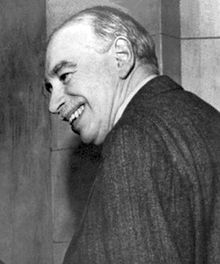

Macroeconomics as a separate field of research and study is generally recognized to start in 1936, whenJohn Maynard Keynespublished hisThe General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money,but its intellectual predecessors are much older. Since World War II, various macroeconomic schools of thought likeKeynesians,monetarists,new classicalandnew Keynesian economistshave made contributions to the development of themacroeconomic research mainstream.

Basic macroeconomic concepts

[edit]Macroeconomics encompasses a variety of concepts and variables, but above all the three central macroeconomic variables are output, unemployment, and inflation.[5]: 39 Besides, the time horizon varies for different types of macroeconomic topics, and this distinction is crucial for many research and policy debates.[5]: 54 A further important dimension is that of an economy's openness, economic theory distinguishing sharply betweenclosed economiesandopen economies.[5]: 373

Time frame

[edit]It is usual to distinguish between three time horizons in macroeconomics, each having its own focus on e.g. the determination of output:[5]: 54

- the short run (e.g. a few years): Focus is onbusiness cyclefluctuations and changes inaggregate demandwhich often drive them.Stabilization policieslikemonetary policyorfiscal policyare relevant in this time frame

- the medium run (e.g. a decade): Over the medium run, the economy tends to an output level determined by supply factors like the capital stock, the technology level and the labor force, and unemployment tends to revert to its structural (or "natural" ) level. These factors move slowly, so that it is a reasonable approximation to take them as given in a medium-term time scale, thoughlabour market policiesandcompetition policyare instruments that may influence the economy's structures and hence also the medium-run equilibrium

- the long run (e.g. a couple of decades or more): On this time scale, emphasis is on the determinants of long-runeconomic growthlikeaccumulationof human and physical capital, technological innovations anddemographic changes.Potential policies to influence these developments areeducation reforms,incentives to changesaving ratesor to increaseR&Dactivities.

Output and income

[edit]Nationaloutputis the total amount of everything a country produces in a given period of time. Everything that is produced and sold generates an equal amount of income. The totalnet outputof the economy is usually measured asgross domestic product(GDP). Adding netfactor incomesfrom abroad to GDP producesgross national income(GNI), which measures total income of all residents in the economy. In most countries, the difference between GDP and GNI are modest so that GDP can approximately be treated as total income of all the inhabitants as well, but in some countries, e.g. countries with very largenet foreign assets(or debt), the difference may be considerable.[5]: 385

Economists interested in long-run increases in output study economic growth. Advances in technology, accumulation of machinery and othercapital,and better education andhuman capital,are all factors that lead to increased economic output over time. However, output does not always increase consistently over time.Business cyclescan cause short-term drops in output calledrecessions.Economists look formacroeconomic policiesthat prevent economies from slipping into eitherrecessionsoroverheatingand that lead to higherproductivitylevels andstandards of living.

Unemployment

[edit]

The amount ofunemploymentin an economy is measured by the unemployment rate, i.e. the percentage of persons in thelabor forcewho do not have a job, but who are actively looking for one. People who are retired, pursuing education, ordiscouraged from seeking workby a lack of job prospects are not part of the labor force and consequently not counted as unemployed, either.[5]: 156

Unemployment has a short-run cyclical component which depends on the business cycle, and a more permanent structural component, which can be loosely thought of as the average unemployment rate in an economy over extended periods,[6]and which is often termed thenatural[6]or structural[7][5]: 167 rate of unemployment.

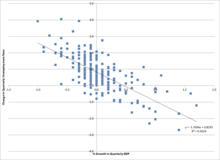

Cyclical unemploymentoccurs when growth stagnates.Okun's lawrepresents the empirical relationship between unemployment and short-run GDP growth.[8]The original version of Okun's law states that a 3% increase in output would lead to a 1% decrease in unemployment.[9]

The structural or natural rate of unemployment is the level of unemployment that will occur in a medium-run equilibrium, i.e. a situation with a cyclical unemployment rate of zero. There may be several reasons why there is some positive unemployment level even in a cyclically neutral situation, which all have their foundation in some kind ofmarket failure:[6]

- Search unemployment(also called frictional unemployment) occurs when workers and firms are heterogeneous and there isimperfect information,generally causing a time-consumingsearch and matching processwhen filling a job vacancy in a firm, during which the prospective worker will often be unemployed.[6][10]Sectoral shifts and other reasons for a changed demand from firms for workers with particular skills and characteristics, which occur continually in a changing economy, may also cause more search unemployment because of increased mismatch.[11][12][13]

- Efficiency wagemodels are labor market models in which firms choose not to lower wages to the level where supply equals demand because the lower wages would lower employees' efficiency levels[11]

- Trade unions,which are important actors in the labor market in some countries, may exercisemarket powerin order to keep wages over the market-clearing level for the benefice of their members even at the cost of some unemployment

- Legalminimum wagesmay prevent the wage from falling to a market-clearing level, causing unemployment among low-skilled (and low-paid) workers.[11][14]In the case of employers having somemonopsony power,however, employment effects may have the opposite sign.[15]

Inflation and deflation

[edit]

A general price increase across the entire economy is calledinflation.When prices decrease, there isdeflation.Economists measure these changes in prices withprice indexes.Inflation will increase when an economy becomes overheated and grows too quickly. Similarly, a declining economy can lead to decreasing inflation and even in some cases deflation.

Central bankersconductingmonetary policyusually have as a main priority to avoid too high inflation, typically by adjusting interest rates. High inflation as well as deflation can lead to increased uncertainty and other negative consequences, in particular when the inflation (or deflation) is unexpected. Consequently, most central banks aim for a positive, but stable and not very high inflation level.[5]

Changes in the inflation level may be the result of several factors. Too muchaggregate demandin the economy will cause anoverheating,raising inflation rates via thePhillips curvebecause of a tight labor market leading to large wage increases which will betransmittedto increases in the price of the products of employers. Too little aggregate demand will have the opposite effect of creating more unemployment and lower wages, thereby decreasing inflation. Aggregatesupply shockswill also affect inflation, e.g. theoil crises of the 1970sand the2021–2023 global energy crisis.Changes in inflation may also impact the formation ofinflation expectations,creating a self-fulfilling inflationary or deflationary spiral.[5]

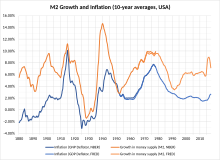

Themonetaristquantity theory of moneyholds that changes in the price level are directly caused by changes in themoney supply.[16]Whereas there is empirical evidence that there is a long-run positive correlation between the growth rate of the money stock and the rate of inflation, the quantity theory has proved unreliable in the short- and medium-run time horizon relevant to monetary policy and is abandoned as a practical guideline by most central banks today.[17]

Open economy macroeconomics

[edit]Open economymacroeconomics deals with the consequences ofinternational tradeingoods,financial assetsand possiblyfactor marketslikelabor migrationand international relocation of firms (physical capital). It explores what determinesimport,export,thebalance of tradeand over longer horizons the accumulation ofnet foreign assets.An important topic is the role ofexchange ratesand the pros and cons of maintaining afixed exchange ratesystem or even acurrency unionlike theEconomic and Monetary Union of the European Union,drawing on the research literature onoptimum currency areas.[5]

Development

[edit]

Macroeconomics as a separate field of research and study is generally recognized to start with the publication ofJohn Maynard Keynes'The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Moneyin 1936.[18][19][5]: 526 The terms "macrodynamics" and "macroanalysis" were introduced byRagnar Frischin 1933, and Lawrence Klein in 1946 used the word "macroeconomics" itself in a journal title in 1946.[18]but naturally several of the themes which are central to macroeconomic research had been discussed by thoughtful economists and other writers long before 1936.[18]

Before Keynes

[edit]In particular, macroeconomic questions before Keynes were the topic of the two long-standing traditions ofbusiness cycle theoryandmonetary theory.William Stanley Jevonswas one of the pioneers of the first tradition, whereas thequantity theory of money,labelled the oldest surviving theory in economics, as an example of the second was described already in the 16th century byMartín de Azpilcuetaand later discussed by personalities likeJohn LockeandDavid Hume.In the first decades of the 20th century monetary theory was dominated by the eminent economistsAlfred Marshall,Knut WicksellandIrving Fisher.[18]

Keynes and Keynesian economics

[edit]When the Great Depression struck, the reigning economists had difficulty explaining how goods could go unsold and workers could be left unemployed. In the prevailingneoclassical economicsparadigm, prices and wages would drop until the market cleared, and all goods and labor were sold. Keynes in his main work, theGeneral Theory,initiated what is known as theKeynesian revolution.He offered a new interpretation of events and a whole intellectural framework - a novel theory of economics that explained why markets might not clear, which would evolve into a school of thought known asKeynesian economics,also called Keynesianism or Keynesian theory.[5]: 526

In Keynes' theory,aggregate demand- by Keynes called "effective demand" - was key to determining output. Even if Keynes conceded that output might eventually return to a medium-run equilibrium (or "potential" ) level, the process would be slow at best. Keynes coined the termliquidity preference(his preferred name for what is also known asmoney demand) and explained how monetary policy might affect aggregate demand, at the same time offering clear policy recommendations for an active role of fiscal policy in stabilizing aggregate demand and hence output and employment. In addition, he explained how themultiplier effectwould magnify a small decrease in consumption or investment and cause declines throughout the economy, and noted the role that uncertainty andanimal spiritscan play in the economy.[5]: 526

The generation following Keynes combined the macroeconomics of theGeneral Theorywith neoclassical microeconomics to create theneoclassical synthesis.By the 1950s, most economists had accepted the synthesis view of the macroeconomy.[5]: 526 Economists likePaul Samuelson,Franco Modigliani,James Tobin,andRobert Solowdeveloped formal Keynesian models and contributed formal theories of consumption, investment, and money demand that fleshed out the Keynesian framework.[5]: 527

Monetarism

[edit]Milton Friedmanupdated the quantity theory of money to include a role for money demand. He argued that the role of money in the economy was sufficient to explain theGreat Depression,and that aggregate demand oriented explanations were not necessary. Friedman also argued that monetary policy was more effective than fiscal policy; however, Friedman doubted the government's ability to "fine-tune" the economy with monetary policy. He generally favored a policy of steady growth in money supply instead of frequent intervention.[5]: 528

Friedman also challenged the original simplePhillips curverelationship between inflation and unemployment. Friedman andEdmund Phelps(who was not a monetarist) proposed an "augmented" version of the Phillips curve that excluded the possibility of a stable, long-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment.[20]When theoil shocksof the 1970s created a high unemployment and high inflation, Friedman and Phelps were vindicated. Monetarism was particularly influential in the early 1980s, but fell out of favor when central banks found the results disappointing when trying to target money supply instead of interest rates as monetarists recommended, concluding that the relationships between money growth, inflation and real GDP growth are too unstable to be useful in practical monetary policy making.[21]

New classical economics

[edit]New classical macroeconomicsfurther challenged the Keynesian school. A central development in new classical thought came whenRobert Lucasintroducedrational expectationsto macroeconomics. Prior to Lucas, economists had generally usedadaptive expectationswhere agents were assumed to look at the recent past to make expectations about the future. Under rational expectations, agents are assumed to be more sophisticated.[5]: 530 Consumers will not simply assume a 2% inflation rate just because that has been the average the past few years; they will look at current monetary policy and economic conditions to make an informed forecast. In the new classical models with rational expectations, monetary policy only had a limited impact.

Lucas also made aninfluential critiqueof Keynesian empirical models. He argued that forecasting models based on empirical relationships would keep producing the same predictions even as the underlying model generating the data changed. He advocated models based on fundamental economic theory (i.e. having an explicitmicroeconomic foundation) that would, in principle, be structurally accurate as economies changed.[5]: 530

Following Lucas's critique, new classical economists, led byEdward C. PrescottandFinn E. Kydland,createdreal business cycle(RBC) models of the macro economy. RBC models were created by combining fundamental equations from neo-classical microeconomics to make quantitative models. In order to generate macroeconomic fluctuations, RBC models explained recessions and unemployment with changes in technology instead of changes in the markets for goods or money. Critics of RBC models argue that technological changes, which typically diffuse slowly throughout the economy, could hardly generate the large short-run output fluctuations that we observe. In addition, there is strong empirical evidence that monetary policy does affect real economic activity, and the idea that technological regress can explain recent recessions seems implausible.[5]: 533 [6]: 195

Despite criticism of the realism in the RBC models, they have been very influential ineconomic methodologyby providing the first examples ofgeneral equilibriummodels based onmicroeconomic foundationsand a specification of underlying shocks that aim to explain the main features of macroeconomic fluctuations, not only qualitatively, but also quantitatively. In this way, they were forerunners of the later DSGE models.[6]: 194

New Keynesian response

[edit]New Keynesianeconomists responded to the new classical school by adopting rational expectations and focusing on developing micro-founded models that were immune to the Lucas critique. Like classical models, new classical models had assumed that prices would be able to adjust perfectly and monetary policy would only lead to price changes. New Keynesian models investigated sources ofsticky prices and wagesdue toimperfect competition,[22]which would not adjust, allowing monetary policy to impact quantities instead of prices.Stanley FischerandJohn B. Taylorproduced early work in this area by showing that monetary policy could be effective even in models with rational expectations when contracts locked in wages for workers. Other new Keynesian economists, includingOlivier Blanchard,Janet Yellen,Julio Rotemberg,Greg Mankiw,David Romer,andMichael Woodford,expanded on this work and demonstrated other cases where various market imperfections caused inflexible prices and wages leading in turn to monetary and fiscal policy having real effects. Other researchers focused on imperferctions in labor markets, developing models ofefficiency wagesorsearch and matching(SAM) models, or imperfections in credit markets likeBen Bernanke.[5]: 532–36

By the late 1990s, economists had reached a rough consensus.[23]The market imperfections and nominal rigidities of new Keynesian theory was combined with rational expectations and the RBC methodology to produce a new and popular type of models calleddynamic stochastic general equilibrium(DSGE) models. The fusion of elements from different schools of thought has been dubbed thenew neoclassical synthesis.[24][25]These models are now used by many central banks and are a core part of contemporary macroeconomics.[5]: 535–36

After the global financial crisis

[edit]Theglobal financial crisisleading to theGreat Recessionled to major reassessment of macroeconomics, which as a field generally had neglected the potential role offinancial institutionsin the economy. After the crisis, macroeconomic researchers have turned their attention in several new directions:

- the financial system and the nature of macrofinancial linkages and frictions, studying leverage, liquidity and complexity problems in the financial sector, the use ofmacroprudential toolsand the dangers of anunsustainablepublic debt[5]: 537 [26]

- increased emphasis onempirical workas part of the so-calledcredibility revolutionin economics, using improved methods to distinguish betweencorrelation and causalityto improve future policy discussions[27]

- interest in understanding the importance ofheterogeneityamong the economic agents, leading among other examples to the construction of heterogeneous agent new Keynesian models (HANK models), which may potentially also improve understanding of the impact of macroeconomics on theincome distribution[28]

- understanding the implications of integrating the findings of the increasingly usefulbehavioral economicsliterature into macroeconomics[29]and behavioral finance

Growth models

[edit]Research in the economics of the determinants behind long-runeconomic growthhas followed its own course.[30]TheHarrod-Domarmodel from the 1940s attempted to build a long-run growth model inspired by Keynesian demand-driven considerations.[31]TheSolow–Swan modelworked out byRobert Solowand, independently,Trevor Swanin the 1950s achieved more long-lasting success, however, and is still today a common textbook model for explaining economic growth in the long-run.[32]The model operates with aproduction functionwhere national output is the product of two inputs: capital and labor. The Solow model assumes that labor and capital are used at constant rates without the fluctuations in unemployment and capital utilization commonly seen in business cycles.[33]In this model, increases in output, i.e. economic growth, can only occur because of an increase in the capital stock, a larger population, or technological advancements that lead to higher productivity (total factor productivity). An increase in the savings rate leads to a temporary increase as the economy creates more capital, which adds to output. However, eventually the depreciation rate will limit the expansion of capital: savings will be used up replacing depreciated capital, and no savings will remain to pay for an additional expansion in capital. Solow's model suggests that economic growth in terms of output per capita depends solely on technological advances that enhance productivity.[34]The Solow model can be interpreted as a special case of the more generalRamsey growth model,where households' savings rates are not constant as in the Solow model, but derived from an explicit intertemporalutility function.

In the 1980s and 1990sendogenous growth theoryarose to challenge the neoclassical growth theory of Ramsey and Solow. This group of models explains economic growth through factors such as increasing returns to scale for capital andlearning-by-doingthat are endogenously determined instead of the exogenous technological improvement used to explain growth in Solow's model.[35]Another type of endogenous growth models endogenized the process of technological progress by modellingresearch and developmentactivities by profit-maximizing firms explicitly within the growth models themselves.[7]: 280–308

Environmental and climate issues

[edit]

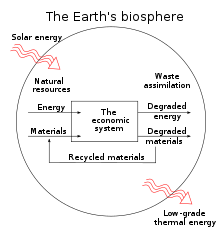

Since the 1970s, various environmental problems have been integrated into growth and other macroeconomic models to study their implications more thoroughly. During the oil crises of the 1970s when scarcity problems of natural resources were high on the public agenda, economists likeJoseph StiglitzandRobert Solowintroducednon-renewable resourcesinto neoclassical growth models to study the possibilities of maintaining growth in living standards under these conditions.[7]: 201–39 More recently, the issue ofclimate changeand the possibilities of asustainable developmentare examined in so-calledintegrated assessment models,pioneered byWilliam Nordhaus.[36]In macroeconomic models inenvironmental economics,the economic system is dependant upon the environment. In this case, thecircular flow of incomediagram may be replaced by a more complex flow diagram reflecting the input of solar energy, which sustains natural inputs andenvironmental serviceswhich are then used as units ofproduction.Once consumed, natural inputs pass out of the economy as pollution and waste. The potential of an environment to provide services and materials is referred to as an "environment's source function", and this function is depleted as resources are consumed or pollution contaminates the resources. The "sink function" describes an environment's ability to absorb and render harmless waste and pollution: when waste output exceeds the limit of the sink function, long-term damage occurs.[37]: 8

Macroeconomic policy

[edit]The division into various time frames of macroeconomic research leads to a parallel division of macroeconomic policies into short-run policies aimed at mitigating the harmful consequences of business cycles (known asstabilization policy) and medium- and long-run policies targeted at improving the structural levels of macroeconomic variables.[7]: 18

Stabilization policy is usually implemented through two sets of tools: fiscal and monetary policy. Both forms of policy are used tostabilize the economy,i.e. limiting the effects of the business cycle by conducting expansive policy when the economy is in arecessionor contractive policy in the case ofoverheating.[5][38]

Structural policies may be labor market policies which aim to change the structural unemployment rate or policies which affect long-run propensities to save, invest, or engage in education or research and development.[7]: 19

Monetary policy

[edit]Central banksconduct monetary policy mainly by adjusting short-terminterest rates.[39]The actual method through which the interest rate is changed differs from central bank to central bank, but typically the implementation happens either directly via administratively changing the central bank's own offered interest rates or indirectly viaopen market operations.[40]

Via themonetary transmission mechanism,interest rate changes affectinvestment,consumption,asset priceslikestock pricesandhouse prices,and throughexchange ratereactionsexportandimport.In this wayaggregate demand,employmentand ultimately inflation is affected.[41]Expansionary monetary policy lowers interest rates, increasing economic activity, whereas contractionary monetary policy raises interest rates. In the case of a fixed exchange rate system, interest rate decisions together with direct intervention by central banks on exchange rate dynamics are major tools to control the exchange rate.[42]

In developed countries, most central banks followinflation targeting,focusing on keeping medium-term inflation close to an explicit target, say 2%, or within an explicit range. This includes theFederal Reserveand theEuropean Central Bank,which are generally considered to follow a strategy very close to inflation targeting, even though they do not officially label themselves as inflation targeters.[43]In practice, an official inflation targeting often leaves room for the central bank to also help stabilizeoutputand employment, a strategy known as "flexible inflation targeting".[44]Mostemerging economiesfocus their monetary policy on maintaining afixed exchange rateregime, aligning their currency with one or more foreign currencies, typically theUS dollaror theeuro.[45]

Conventional monetary policy can be ineffective in situations such as aliquidity trap.When nominal interest rates are near zero, central banks cannot loosen monetary policy through conventional means. In that situation, they may use unconventional monetary policy such asquantitative easingto help stabilize output. Quantity easing can be implemented by buying not only government bonds, but also other assets such as corporate bonds, stocks, and other securities. This allows lower interest rates for a broader class of assets beyond government bonds. A similar strategy is to lower long-term interest rates by buying long-term bonds and selling short-term bonds to create a flatyield curve,known in the US asOperation Twist.[46]

Fiscal policy

[edit]Fiscal policy is the use of government's revenue (taxes) andexpenditureas instruments to influence the economy.

For example, if the economy is producing less thanpotential output,government spending can be used to employ idle resources and boost output, or taxes could be lowered to boost private consumption which has a similar effect. Government spending or tax cuts do not have to make up for the entireoutput gap.There is amultiplier effectthat affects the impact of government spending. For instance, when the government pays for a bridge, the project not only adds the value of the bridge to output, but also allows the bridge workers to increase their consumption and investment, which helps to close the output gap.

The effects of fiscal policy can be limited by partial or fullcrowding out.When the government takes on spending projects, it limits the amount of resources available for theprivate sectorto use. Full crowding out occurs in the extreme case when government spending simply replaces private sector output instead of adding additional output to the economy. A crowding out effect may also occur if government spending should lead to higher interest rates, which would limit investment.[47]

Some fiscal policy is implemented throughautomatic stabilizerswithout any active decisions by politicians. Automatic stabilizers do not suffer from the policy lags ofdiscretionary fiscal policy.Automatic stabilizers use conventional fiscal mechanisms, but take effect as soon as the economy takes a downturn: spending on unemployment benefits automatically increases when unemployment rises, andtax revenuesdecrease, which shelters private income and consumption from part of the fall in market income.[7]: 657

Comparison of fiscal and monetary policy

[edit]There is a general consensus that both monetary and fiscal instruments may affect demand and activity in the short run (i.e. over the business cycle).[7]: 657 Economists usually favor monetary over fiscal policy to mitigate moderate fluctuations, however, because it has two major advantages. First, monetary policy is generally implemented by independent central banks instead of the political institutions that control fiscal policy. Independent central banks are less likely to be subject to political pressures for overly expansionary policies. Second, monetary policy may suffer shorterinside lagsandoutside lagsthan fiscal policy.[38]There are some exceptions, however: Firstly, in the case of a major shock, monetary stabilization policy may not be sufficient and should be supplemented by active fiscal stabilization.[7]: 659 Secondly, in the case of a very low interest level, the economy may be in aliquidity trapin which monetary policy becomes ineffective, which makes fiscal policy the more potent tool to stabilize the economy.[5]Thirdly, in regimes where monetary policy is tied to fulfilling other targets, in particularfixed exchange rateregimes, the central bank cannot simultaneously adjust its interest rates to mitigate domestic business cycle fluctuations, making fiscal policy the only usable tool for such countries.[42]

Macroeconomic models

[edit]Macroeconomic teaching, research and informed debates normally evolve around formal (diagrammaticorequational)macroeconomic modelsto clarify assumptions and show their consequences in a precise way. Models include simple theoretical models, often containing only a few equations, used in teaching and research to highlight key basic principles, and larger applied quantitative models used by e.g. governments, central banks, think tanks and international organisations to predict effects of changes in economic policy or otherexogenous factorsor as a basis for makingeconomic forecasting.[48]

Well-known specific theoretical models include short-term models like theKeynesian cross,theIS–LM modeland theMundell–Fleming model,medium-term models like theAD–AS model,building upon aPhillips curve,and long-term growth models like theSolow–Swanmodel, theRamsey–Cass–Koopmans modelandPeter Diamond'soverlapping generations model.Quantitative models include earlylarge-scale macroeconometric model,the new classicalreal business cycle models,microfoundedcomputable general equilibrium(CGE) models used for medium-term (structural) questions like international trade or tax reforms,Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium(DSGE) models used to analyze business cycles, not least in many central banks, orintegrated assessmentmodels likeDICE.

Specific models

[edit]IS–LM model

[edit]

TheIS–LMmodel, invented byJohn Hicksin 1936, gives the underpinnings of aggregate demand (itself discussed below). It answers the question "At any given price level, what is the quantity of goods demanded?" The graphic model shows combinations of interest rates and output that ensure equilibrium in both the goods and money markets under the model's assumptions.[49]The goods market is modeled as giving equality between investment and public and private saving (IS), and the money market is modeled as giving equilibrium between themoney supplyandliquidity preference(equivalent to money demand).[50]

The IS curve consists of the points (combinations of income and interest rate) where investment, given the interest rate, is equal to public and private saving, given output.[51]The IS curve is downward sloping because output and the interest rate have an inverse relationship in the goods market: as output increases, more income is saved, which means interest rates must be lower to spur enough investment to match saving.[51]

The traditional LM curve is upward sloping because the interest rate and output have a positive relationship in the money market: as income (identically equal to output in a closed economy) increases, the demand for money increases, resulting in a rise in the interest rate in order to just offset the incipient rise in money demand.[52]

The IS-LM model is often used in elementary textbooks to demonstrate the effects of monetary and fiscal policy, though it ignores many complexities of most modern macroeconomic models.[49]A problem related to the LM curve is that modern central banks largely ignore the money supply in determining policy, contrary to the model's basic assumptions.[6]: 262 In some modern textbooks, consequently, the traditional IS-LM model has been modified by replacing the traditional LM curve with an assumption that the central bank simply determines the interest rate of the economy directly.[6]: 194 [5]: 113

AD-AS model

[edit]

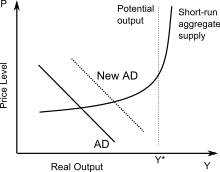

TheAD–AS modelis a common textbook model for explaining the macroeconomy.[53]The original version of the model shows the price level and level of real output given the equilibrium inaggregate demandandaggregate supply.The aggregate demand curve's downward slope means that more output is demanded at lower price levels.[54]The downward slope can be explained as the result of three effects: thePigou or real balance effect,which states that as real prices fall, real wealth increases, resulting in higher consumer demand of goods; theKeynes or interest rate effect,which states that as prices fall, the demand for money decreases, causing interest rates to decline and borrowing for investment and consumption to increase; and the net export effect, which states that as prices rise, domestic goods become comparatively more expensive to foreign consumers, leading to a decline in exports.[54]

In many representations of the AD–AS model, the aggregate supply curve is horizontal at low levels of output and becomes inelastic near the point ofpotential output,which corresponds withfull employment.[53]Since the economy cannot produce beyond the potential output, any AD expansion will lead to higher price levels instead of higher output.

In modern textbooks, the AD–AS model is often presented sligthly differently, however, in a diagram showing not the price level, but the inflation rate along the vertical axis,[6]: 263 [11]: 399–428 [7]: 595 making it easier to relate the diagram to real-world policy discussions.[7]: vii In this framework, the AD curve is downward sloping because higher inflation will cause the central bank, which is assumed to follow aninflation target,to raise the interest rate which will dampen economic activity, hence reducing output. The AS curve is upward sloping following a standard modernPhillips curvethought, in which a higher level of economic activity lowers unemployment, leading to higher wage growth and in turn higher inflation.[6]: 263

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Samuelson, Robert(2020)."Goodbye, readers, and good luck — you'll need it".The Washington Post.This article was an opinion piece expressing despondency in the field shortly before his retirement, but it is still a good summary.

- ^O'Sullivan, Arthur;Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003).Economics: Principles in Action.Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 57.ISBN978-0-13-063085-8.

- ^Steve Williamson,Notes on Macroeconomic Theory,1999

- ^Blaug, Mark (1985),Economic theory in retrospect,Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0-521-31644-6

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyBlanchard (2021).

- ^abcdefghijRomer (2019).

- ^abcdefghijSørensen and Whitta-Jacobsen (2022).

- ^Dwivedi, 445–46.

- ^"Neely, Christopher J." Okun's Law: Output and Unemployment.Economic Synopses.Number 4. 2010 ".

- ^Dwivedi, 443.

- ^abcdMankiw (2022).

- ^"Freeman (2008)".

- ^Dwivedi, 444–45.

- ^Pettinger, Tejvan."Involuntary unemployment".Economics Help.Retrieved2020-09-21.

- ^Dickens, Richard; Machin, Stephen; Manning, Alan (January 1999)."The Effects of Minimum Wages on Employment: Theory and Evidence from Britain".Journal of Labor Economics.17(1): 1–22.doi:10.1086/209911.ISSN0734-306X.S2CID7012497.

- ^Mankiw 2022,p. 98.

- ^Graff, Michael (April 2008)."The quantity theory of money in historical perspective".Kof Working Papers.196.KOF Swiss Economic Institute, ETH Zurich.doi:10.3929/ethz-a-005582276.Retrieved3 September2023.

- ^abcdDimand (2008).

- ^Snowdon and Vane (2005).

- ^"Phillips Curve: The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics | Library of Economics and Liberty".econlib.org.Retrieved2018-01-23.

- ^Williamson, Stephen D. (2020)."The Role of Central Banks".Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques.46(2): 198–213.doi:10.3138/cpp.2019-058.ISSN0317-0861.JSTOR26974728.S2CID219465676.

- ^The role of imperfect competition in new Keynesian economics,Chapter 4 ofSurfing EconomicsbyHuw Dixon

- ^Blanchard (2009).

- ^Goodfriend, Marvin; King, Robert G. (1997)."The New Neoclassical Synthesis and the Role of Monetary Policy".NBER Macroeconomics Annual.12:231–283.doi:10.2307/3585232.JSTOR3585232.Retrieved8 September2023.

- ^Woodford, Michael (January 2009)."Convergence in Macroeconomics: Elements of the New Synthesis".American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics.1(1): 267–279.doi:10.1257/mac.1.1.267.ISSN1945-7707.Retrieved8 September2023.

- ^Glandon, P. J.; Kuttner, Ken; Mazumder, Sandeep; Stroup, Caleb (September 2023)."Macroeconomic Research, Present and Past".Journal of Economic Literature.61(3): 1088–1126.doi:10.1257/jel.20211609.ISSN0022-0515.Retrieved8 September2023.

- ^Nakamura and Steinsson (2018) write that macroeconomics struggles with long-term predictions, which is a result of the high complexity of the systems it studies.

- ^Guvenen, Fatih."Macroeconomics with Heterogeneity: A Practical Guide"(PDF).nber.org.National Bureau of Economic Research.Retrieved8 September2023.

- ^Ji, Yuemei; De Grauwe, Paul (1 November 2017)."Behavioural economics is also useful in macroeconomics".CEPR.Centre for Economic Policy Research.Retrieved8 September2023.

- ^Howitt, Peter; Weil, David N. (2016). "Economic Growth".The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 1–11.doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2314-1.ISBN978-1-349-95121-5.

- ^Eltis, Walter (2016). "Harrod–Domar Growth Model".The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 1–5.doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_1267-1.ISBN978-1-349-95121-5.

- ^Banton, Caroline."The Neoclassical Growth Theory Explained".Investopedia.Retrieved2020-09-21.

- ^Solow 2002,pp. 518–19.

- ^Solow 2002,p. 519.

- ^Blaug 2002,pp. 202–03.

- ^Hassler, J.; Krusell, P.; Smith, A. A. (1 January 2016)."Chapter 24 - Environmental Macroeconomics".Handbook of Macroeconomics.Vol. 2. Elsevier. pp. 1893–2008.doi:10.1016/bs.hesmac.2016.04.007.ISBN9780444594877.Retrieved9 September2023.

- ^Harris J. (2006).Environmental and Natural Resource Economics: A Contemporary Approach.Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^abMayer, 495.

- ^Baker, Nick; Rafter, Sally (16 June 2022)."An International Perspective on Monetary Policy Implementation Systems | Bulletin – June 2022".Reserve Bank of Australia.Retrieved13 August2023.

- ^MC Compendium Monetary policy frameworks and central bank market operations(PDF).Bank for International Settlements. October 2019.ISBN978-92-9259-298-1.

- ^"Federal Reserve Board - Monetary Policy: What Are Its Goals? How Does It Work?".Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.29 July 2021.Retrieved13 August2023.

- ^ab"Fixed exchange rate policy".Nationalbanken.Retrieved13 August2023.

- ^"Inflation Targeting: Holding the Line".International Monetary Fund.Retrieved12 August2023.

- ^Ingves, Stefan (12 May 2011)."Flexible inflation targeting in theory and practice"(PDF).bis.org.Bank of International Settlements.Retrieved5 September2023.

- ^Department, International Monetary Fund Monetary and Capital Markets (26 July 2023).Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions 2022.International Monetary Fund.ISBN979-8-4002-3526-9.Retrieved12 August2023.

- ^Hancock, Diana; Passmore, Wayne (2014)."How the Federal Reserve's Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Influence Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) Yields and U.S. Mortgage Rates"(PDF).federalreserve.gov.Federal Reserve.Retrieved5 September2023.

- ^Arestis, Philip; Sawyer, Malcolm (2003)."Reinventing fiscal policy"(PDF).Levy Economics Institute of Bard College(Working Paper, No. 381).Retrieved7 December2018.

- ^Watson, Mark W. (2016). "Macroeconomic Forecasting".The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 1–3.doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2434-1.ISBN978-1-349-95121-5.Retrieved9 September2023.

- ^abDurlauf & Hester 2008.

- ^Peston 2002,pp. 386–87.

- ^abPeston 2002,p. 387.

- ^Peston 2002,pp. 387–88.

- ^abHealey 2002,p. 12.

- ^abHealey 2002,p. 13.

References

[edit]- Blanchard, Olivier. (2009). "The State of Macro."Annual Review of Economics1(1): 209–228.

- Blanchard, Olivier (2021).Macroeconomics(Eighth, global ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson.ISBN978-0-134-89789-9.

- Blaug, Mark (2002). "Endogenous growth theory". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.).An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics.Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing.ISBN978-1-84542-180-9.

- Dimand, Robert W. (2008)."Macroeconomics, origins and history of".In Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.).The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 236–44.doi:10.1057/9780230226203.1009.ISBN978-0-333-78676-5.

- Durlauf, Steven N.; Hester, Donald D. (2008)."IS–LM".In Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.).The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics(2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 585–91.doi:10.1057/9780230226203.0855.ISBN978-0-333-78676-5.

- Dwivedi, D.N. (2001).Macroeconomics: theory and policy.New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0-07-058841-7.

- Gärtner, Manfred (2006).Macroeconomics.Pearson Education Limited.ISBN978-0-273-70460-7.

- Healey, Nigel M. (2002). "AD-AS model". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.).An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics.Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp.11–18.ISBN978-1-84542-180-9.

- Levi, Maurice (2014).The Macroeconomic Environment of Business (Core Concepts and Curious Connections).New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing.ISBN978-981-4304-34-4.

- Mankiw, Nicholas Gregory (2022).Macroeconomics(Eleventh, international ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers, Macmillan Learning.ISBN978-1-319-26390-4.

- Mayer, Thomas (2002). "Monetary policy: role of". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (eds.).An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics.Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp.495–99.ISBN978-1-84542-180-9.

- Nakamura, Emi and Jón Steinsson. (2018). "Identification in Macroeconomics."Journal of Economic Perspectives32(3): 59–86.

- Peston, Maurice (2002). "IS-LM model: closed economy". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (eds.).An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics.Edward Elgar.ISBN9781840643879.

- Romer, David (2019).Advanced macroeconomics(Fifth ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-1-260-18521-8.

- Solow, Robert (2002). "Neoclassical growth model". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.).An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics.Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing.ISBN1840643870.

- Snowdon, Brian, and Howard R. Vane, ed. (2002).An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics,Description& scroll to Contents-previewlinks.

- Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (2005).Modern Macroeconomics: Its Origins, Development And Current State.Edward Elgar Publishing.ISBN1845421809.

- Sørensen, Peter Birch; Whitta-Jacobsen, Hans Jørgen (2022).Introducing advanced macroeconomics: growth and business cycles(Third ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom New York, NY: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-885049-6.

- Warsh, David (2006).Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations.Norton.ISBN978-0-393-05996-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Glandon, P. J., Ken Kuttner, Sandeep Mazumder, and Caleb Stroup. 2023. "Macroeconomic Research, Present and Past."Journal of Economic Literature,61 (3): 1088-1126.