Menachem HaMeiri

Menachem HaMeiri מנחם המאירי | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Born | 1249 |

| Died | 1315 |

| Religion | Judaism |

Menachem ben Solomon HaMeiri(Hebrew:מנחם בן שלמה המאירי;French:Don Vidal Solomon,1249[1]–1315[2]), commonly referred to asHaMeiri,the Meiri,or justMeiri,was a famous medievalProvençalrabbi,andTalmudist.Though most of his expansive commentary, spanning 35 tractates of theTalmud,was not publicly available until the turn of the 19th century, it has since gained widespread renown and acceptance among Talmudic scholars.

Biography[edit]

Menachem HaMeiri was born in 1249 inPerpignan,which then formed part of thePrincipality of Catalonia.He was the student of Rabbi Reuven, the son of Chaim ofNarbonne,France. In his writings, he refers to himself as HaMeiri ( "the Meiri", or the Meirite;Hebrew:המאירי), presumably after one of his ancestors named Meir (Hebrew: מאיר), and that is how he is now known. Some have suggested that the reference is to Meir Detrancatleich, a student of theRaavad,who is mentioned in the Meiri's writings as one of his elders.[3]

In his youth he was orphaned of his father, and his children were taken captive while he was still young,[4]but no further details of these personal tragedies are known.

From the notorial certificates kept from Perpignan, it appears the Meiri made a living as a money lender, and his income was quite high.

The Meiri's principal teacher was Rabbi Reuven ben Chaim, and he kept a close correspondence and relationship with theRashba,who was arguably the greatest Jewish rabbi of those times. Although the Meiri is known as one of the greatest scholars of his era, and despite his vastTorahknowledge and expertise, as testified to by many rabbis of his time and by his great expansive workBeit HaBechirah,there is no evidence he ever held a rabbinic position, or even a teaching position in aYeshiva(Jewish school for religious studies). This may have been in accordance with the teaching of theRambam,[5]who spoke harshly against turning the rabbinate solely into a means of livelihood.[3]

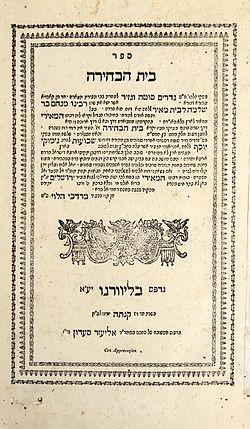

Beit HaBechirah[edit]

His commentary, theBeit HaBechirah(literally "The Chosen House," a play on an alternate name for theTemple in Jerusalem,implying that the Meiri's work selects specific content from the Talmud, omitting the discursive elements), is one of the most monumental works written on theTalmud.This work is less a commentary and more of a digest of all of the comments in the Talmud, arranged in a manner similar to the Talmud—presenting first themishnahand then laying out the discussions that are raised concerning it.[6]Haym Soloveitchikdescribes it as follows:[7]

- Meiri is the only medieval Talmudist (rishon) whose works can be read almost independently of the Talmudic text, upon which it ostensibly comments. The Beit ha-Behirah is not a running commentary on the Talmud. Meiri, in quasi-Maimonidean fashion, intentionally omits the give and take of thesugya,he focuses, rather, on the final upshot of the discussion and presents the differing views of that upshot and conclusion. Also, he alone, and again intentionally, provides the reader with background information. His writings are the closest thing to a secondary source in the library of rishonim.

Unlike mostrishonim,he frequently quotes theJerusalem Talmud,including textual variants which are no longer extant in other sources.

Beit HaBechirahcites many of the majorRishonim,referring to them not by name but rather by distinguished titles. Specifically:[3]

- Gedolei HaRabbanim( "The Greatest of the Rabbis" ) –Rashi

- Gedolei HaMefarshim( "The Greatest of the Commentators" ) –Raavad(orGedolei HaMagihim,"The Greatest of the Annotaters", when quoted as disputing Rambam or Rif)

- Gedolei HaPoskim( "The Greatest of thePoskim") –Isaac Alfasi

- Gedolei HaMechabrim( "The Greatest of the Authors" ) –Rambam

- Geonei Sefarad( "The Brilliant of Spain" ) –Ri Migash(or, sometimesRabbeinu Chananel)

- Chachmei HaTzarfatim( "The Wise of France" ) –Rashbam(or, sometimesRashi)

- Achronei HaRabbonim( "The Later of the Rabbis" ) –Rabbeinu Tam

- Gedolei HaDor( "The Greatest of the Generation" ) –Rashba

Historical influence[edit]

A complete copy ofBeit HaBechirawas preserved in theBiblioteca Palatina in Parma,rediscovered in 1920, and subsequently published.[8]Snippets ofBeit HaBechirahon one Tractate, Bava Kamma, were published long before the publication of the Parma manuscripts, included in the early collective workShitah Mikubetzet.[3]The common assumption has been that the large majority of the Meiri's works were not available to generations of halachists before 1920; as reflected in early 20th century authors such as theChafetz Chaim,theChazon Ish,andJoseph B. Soloveitchikwhom write under the assumption thatBeit HaBechirawas newly discovered in their time,[8]and further evidenced by the lack of mention of the Meiri and his opinions in the vast literature of halacha writings before the early 20th century.[3]

Beit HaBechirahas had much less influence on subsequenthalachicdevelopment than would have been expected given its stature.[citation needed]Several reasons have been given for this. Some modernposkimrefuse to take its arguments into consideration, on the grounds that a work so long unknown has ceased to be part of the process of halachic development.[8]One source held that the work was ignored due to its unusual length.[8]ProfessorHaym Soloveitchik,though, suggested that the work was ignored due to its having the character of a secondary source – a genre which, he argues, was not appreciated among Torah learners until the late 20th century.[9][7]

Other works[edit]

Menachem HaMeiri is also noted for having penned a famous work used to this very day by Jewishscribes,namely,Kiryat Sefer,a two-volume compendium outlining the rules governing theorthographythat are to be adhered to when writingTorahscrolls.[10]

He also wrote several minor works, including a commentary toAvotwhose introduction includes a recording of the chain of tradition fromMosesthrough theTanaim.

The Meiri also wrote a few commentaries (Chidushim) on several tractates of theTalmudwhich differ to some extent from some of his positions inBeit HaBechira.Most of these commentaries were lost, except for the commentary on TractateBeitza.In addition, a commentary on TractateEruvinwas attributed to him, but this attribution was probably a mistake.[11]

Halakhic positions[edit]

The Meiri's commentary is noted for its position on the status ofgentilesin Jewish law, asserting that discriminatory laws and statements found in the Talmud applied only to the idolatrous nations of old.[12][13]

According toJ. David Bleich,"the Christianity presented so favorably by Me’iri was not an orthodox Trinitarianism but a Christianity that espoused a theology formally branded heretical by the Church".[14]However,Yaakov Elmanargued that Bleich had no sources for this assertion.[15]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Israel Ta Shma,Hasifrut Haparshani LaTalmud,pp. 158-9 in volume 2, revised edition

- ^Jacob Katz,Exclusiveness and Tolerance,p. 114, footnote 3, saying that the date is contested, but that Zobel supports a date of 1315

- ^abcde"המאירי, מחבר פורה שספריו כמעט ונשכחו - ספרים".Archived fromthe originalon 2016-05-29.

- ^Kiryat Sefer, by the Meiri, Introduction

- ^Rambam, Commentary toPirkei Avot,4:7

- ^Jewish History – Biographies, letter R

- ^ab"Rupture and Reconstruction: The Transformation of Contemporary Orthodoxy".Archived fromthe originalon 2020-08-07.Retrieved2018-07-03.

- ^abcd"112) the Meiri Texts – Lost or Ignored?".

- ^Soloveitchik (1994),p. 335; note 54, p. 367f.

- ^Two editions of this work were printed in Jerusalem, one in 1956, another in 1969.

- ^Breuer, Adiel (2021)."Ḥidushim on Tractate ꜤEruvin Attributed to Hameiri".Tarbiz.88.1:73–107.

- ^Moshe Halbertal."'Ones possessed of religion': religious tolerance in the teachings of the Me'iri "(PDF).The Edah Journal.1(1).

- ^David Goldstein, "A Lonely Champion of Tolerance: R. Menachem ha-Meiri's Attitude Towards Non-Jews"

- ^Survey of Recent Halakhic Periodical Literature

- ^In theDavid Bergerfestschrifton Jewish-Christian relations (edited byElisheva CarlebachandJ.J. Schacter)

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Singer, Isidore;et al., eds. (1901–1906)."ME'IRI, MENAHEM BEN SOLOMON".The Jewish Encyclopedia.New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Singer, Isidore;et al., eds. (1901–1906)."ME'IRI, MENAHEM BEN SOLOMON".The Jewish Encyclopedia.New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Bibliography[edit]

- Soloveitchik, Haym(1994). "Rupture and reconstruction: the transformation of contemporary orthodoxy".Tradition.28(4): 320–376.