Meroë

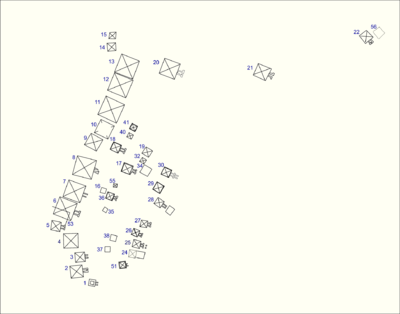

Pyramids of the Kushite rulers at Meroë, covering a period from 300 BC to about 350 AD | |

| Alternative name | Meroe |

|---|---|

| Location | River Nile,Sudan |

| Region | Kush |

| Coordinates | 16°56′00″N33°43′35″E/ 16.93333°N 33.72639°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Official name | Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, vi, v |

| Designated | 2011(35thsession) |

| Reference no. | 1336 |

| Region | Africa |

Meroë(/ˈmɛroʊiː/;[1]also spelledMeroe;[2]Meroitic:Medewi;Arabic:مرواه,romanized:Meruwahandمروي,Meruwi;Ancient Greek:Μερόη,romanized:Meróē) was an ancient city on the east bank of theNileabout 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station nearShendi,Sudan,approximately 200 km north-east ofKhartoum.Near the site is a group of villages calledBagrawiyah(Arabic:البجراوية). This city was the capital of theKingdom of Kushfor several centuries from around 590 BC, until itscollapsein the 4th century AD. The Kushitic Kingdom of Meroë gave its name to the "Island of Meroë", which was the modern region ofButana,a region bounded by the Nile (from theAtbarah RivertoKhartoum), the Atbarah and theBlue Nile.

The city of Meroë was on the edge ofButana.There were two other Meroitic cities in Butana:Musawwarat es-SufraandNaqa.[3][4]The first of these sites was given the name Meroë by the Persian kingCambyses,in honor of his sister who was called by that name. The city had originally borne the ancient appellationSaba,named after the country's original founder.[5]The eponymSaba,orSeba,is named for one of the sons ofCush(see Genesis 10:7). The presence of numerous Meroitic sites within the western Butana region and on the border of Butana proper is significant to the settlement of the core of the developed region. The orientation of these settlements exhibit the exercise of state power over subsistence production.[6]

TheKingdom of Kushwhich housed the city of Meroë represents one of a series of early states located within the middle Nile. It was one of the earliest and most advanced states found on the African continent. Looking at the specificity of the surrounding early states within the middle Nile, one's understanding of Meroë in combination with the historical developments of other historic states may be enhanced through looking at the development of power relation characteristics within other Nile Valley states.[6]

The site of the city of Meroë is marked by more than two hundredpyramidsin three groups, of which many are in ruins. They have the distinctive size and proportions ofNubian pyramids.

History[edit]

| mjrwjwꜣt[7] inhieroglyphs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Meroë was the southern capital of theKingdom of Kush.The Kingdom of Kush spanned the periodc.800 BC – c. 350 AD. Initially, its main capital was farther north atNapata.[8]KingAspeltamoved the capital to Meroë, considerably farther south thanNapata,possibly c. 591 BC,[9]just after the sack of Napata by Egyptian PharaohPsamtik II.

Martin Meredithstates the Kushite rulers chose Meroë, between theFifth and Sixth Cataracts,because it was on the fringe of the summer rainfall belt, and the area was rich in iron ore and hardwood foriron working.The location also afforded access to trade routes to theRed Sea.The city of Meroë was located along the middle Nile which is of much importance due to the annual flooding of the Nile river valley and the connection to many major river systems such as the Niger which aided with the production of pottery and iron characteristic to the Meroitic kingdom that allowed for the rise in power of its people.[6]According to partially deciphered Meroitic texts, Meroitic "d" was transcribed in foreign languages as "r",[10]with the native name of the city beingMedewi.

First Meroitic Period (542–315 BC)[edit]

The Kings ruled overNapataand Meroë. Theseat of governmentand the royal palace were inMeroë.The Main temple of Amun was located inNapata.Kings and many queens are buried inNuri,some queens are buried inMeroë,in the West Cemetery.[11]The earliest king wasAnalmaye(542–538 BC) and the last king of the first phase isNastasen(335–315 BC)

In the fifth century BC, Greek historianHerodotusdescribed it as "a great city...said to be the mother city of the other Ethiopians."[12][13]

Excavations revealed evidence of important, high ranking Kushite burials from the Napatan Period (c. 800 – c. 280 BC) in the vicinity of the settlement called the Western Cemetery. The importance of the town gradually increased fromthe beginning of the Meroitic Period,especially from the reign ofArakamani(c. 280 BC) when the royal burial ground was transferred to Meroë fromNapata(Gebel Barkal). Royal burials formed thePyramids of Meroë,containing the remains of the Kings and Queens of Meroë from c. 300 BC to about 350 AD.[14]

-

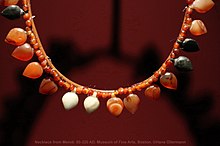

Jewelry found on the mummy of Nubian KingAmaninatakilebte(538–519 BC). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

-

Stela of kingSiaspiqa(487–468 BC).

-

Portrait of KingNastasen(330–310 BC)

Second Meroitic Period (3rd century BC)[edit]

Theseat of governmentand the royal palace are in Meroë. Kings and many queens are buried inMeroë,in the South Cemetery. Napata remained relevant for the Amun Temple.[11]The first King of the period wasAktisanes(Early 3rd century BC) and the last king of the period wasSabrakamani(first half 3rd century BC).

Third Meroitic Period (270 BC – 1st century AD)[edit]

Theseat of governmentand the royal palace are inMeroë.Kings are buried inMeroë,in the North Cemetery, and Queens in West Cemetery. Napata remained relevant for the Amun Temple. Meroë flourished and many building projects were undertaken.[11]The first king of the period isArakamani(270–260 BC), the last ruler is QueenAmanitore(mid/late 1st century AD)

Many artifacts were found in Meroitic tombs from around this time.

-

Pyramids of Meroë- Northern Cemetery

-

QueenShanakdakhete(170–150 BC)

-

Necklace made of 54 composite human head and ram's head gold pendants with a small carnelian bead between each. Meroitic Period, 270–50 BC

-

Golden Bracelet found in the tomb of a member of the royal family inGebel Barkal.250–100 BC

-

KingNatakamani(early 1st century AD)

Conflict with Rome[edit]

Rome's conquest ofEgyptled to border skirmishes and incursions by Meroë beyond the Roman borders. In 23 BC, in response to a Nubian attack on southern Egypt, the Roman governor of Egypt,Publius Petronius,invaded Nubia to end the Meroitic raids. He pillaged northern Nubia and sacked Napata (22 BC) before returning home. In retaliation, the Nubians crossed the lower border of Egypt and looted many statues from the Egyptian towns near the first cataract of the Nile at Aswan. Roman forces later reclaimed many of the statues intact, and others were returned following the peace treaty signed in 22 BC between Rome and Meroë underAugustusandAmanirenas,respectively.One looted head,from a statue of the emperorAugustus,was buried under the steps of a temple; it is now kept in theBritish Museum.[15]

The next recorded contact between Rome and Meroë was in the autumn of 61 AD. The EmperorNerosent a party of Praetorian soldiers under the command of a tribune and two centurions into this country, who reached the city of Meroë where they were given an escort, then proceeded up theWhite Nileuntil they encountered the swamps of theSudd.This marked the limit of Roman penetration into Africa.[16]

The period following Petronius' punitive expedition is marked by abundant trade finds at sites in Meroë.L. P. Kirwanprovides a short list of finds from archeological sites in that country.[16]: 18f The kingdom of Meroë began to fade as a power by the 1st or 2nd century AD, sapped by the war with Roman Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.[17]

Meroë is mentioned briefly in the 1st century ADPeriplus of the Erythraean Sea:

2. On the right-hand coast next belowBereniceis the country of the Berbers. Along the shore are the Fish-Eaters, living in scattered caves in the narrow valleys. Farther inland are the Berbers, and beyond them the Wild-flesh-Eaters and Calf-Eaters, each tribe governed by its chief; and behind them, farther inland, in the country towards the west, there lies a city called Meroe.

— Periplus of the Erythraean Sea,Chap.2

Fourth Meroitic Period (1st century – 4th century AD)[edit]

Kings were buried inMeroë,in the North Cemetery, and Queens in West Cemetery. In 350 ADMeroëwasdestroyedbyAxum.[11]The first king of the fourth period wasShorkaror(1st century AD), while the last rulers may have been KingYesebokheamanior KingTalakhidamaniin the 4th century AD. The Aksumite presence was short lived beforeMeroëwas taken by the Kingdom ofAlodia.

A stele ofGe'ezof an unnamed ruler of theKingdom of Aksumthought to beEzanawas found at the site of Meroë; from its description, inGreek,he was "King of theAksumitesand theOmerites,"(i.e. ofAksumandHimyar) it is likely this king ruled sometime around 330.[18]Another inscription in Greek gives the regnal claims ofEzana:[19][20][21]

I,Ezana,King of theAxumitesandHimyaritesand ofReeidanand of theSabaitesand of Sileel (?) and of Hasa and of the Bougaites and of Taimo...

While some authorities interpret these inscriptions as proof that the Axumites destroyed the Kingdom of Kush, others note that archeological evidence points to an economic and political decline in Meroë around 300.[23]

Meroë in Jewish legend[edit]

Jewish oral tradition avers thatMoses,in his younger years, had led an Egyptian military expedition into Sudan (Kush), as far as the city of Meroë, which was then called Saba. The city was built near the confluence of two great rivers and was encircled by a formidable wall, and governed by a renegade king. To ensure the safety of his men who traversed that desert country, Moses had invented a stratagem whereby the Egyptian army would carry along with them baskets of sedge, each containing an ibis, only to be released when they approached the enemy's country. The purpose of the birds was to kill the deadly serpents that lay all about that country.[5]Having successfully laid siege to the city, the city was eventually subdued by the betrayal of the king's daughter, who had agreed to deliver the city to Moses on condition that he would consummate a marriage with her, under the solemn assurance of an oath.[a]

Civilization[edit]

Meroë was the base of a flourishing kingdom whose wealth was centered around a strongironindustry, as well as international trade involvingIndiaandChina.[24]Metalworking is believed to have taken place in Meroë, possibly throughbloomeriesandblast furnaces.[25]Archibald Saycereportedly referred to it as "theBirminghamof Africa ",[26]because of perceived vast production and trade of iron (a contention that is a matter of debate in modern scholarship).[26][dubious–discuss]

The centralized control of production within the Meroitic empire and distribution of certain crafts and manufactures may have been politically important with their iron industry and pottery crafts gaining the most significant attention. The Meroitic settlements were oriented in a savannah orientation with the varying of permanent and less permanent agricultural settlements can be attributed to the exploitation of rainlands and savannah-oriented forms of subsistence.[6]

At the time, iron was one of the most important metals worldwide, and Meroitic metalworkers were among the best in the world. Meroë traded ivory, slaves, rare skins, ostrich feathers, copper, and ebony.[27]Meroë also exportedtextilesandjewelry.Their textiles were based oncottonand working on this product reached its highest achievement in Nubia around 400 BC. Furthermore,Nubiawas very rich ingold.It is possible that the Egyptian word forgold,nub,was the source of name ofNubia.Trade in "exotic" animals from farther south in Africa was another feature of their economy.

Apart from the iron trade, pottery was a widespread and prominent industry in the Meroë kingdom. The production of fine and elaborately decorated wares was a strong tradition within the middle Nile. Such productions carried considerable social significance and are believed to be involved in mortuary rites. The long history of goods imported into the Meroitic empire and their subsequent distribution provides insight into the social and political workings of the Meroitic state. The major determinant of production was attributed to the availability of labor rather than the political power associated with land. Power was associated with control of people rather than control of territory.[6]

Thesakia,was used to move water, in conjunction with irrigation, to increase crop production.[28]

At its peak, the rulers of Meroë controlled the Nile Valley north to south, over a straight-line distance of more than 1,000 km (620 mi).[29]

The King of Meroë was an autocratic ruler who shared his authority only with the Queen Mother, orCandace.However, the role of the Queen Mother remains obscure. The administration consisted oftreasurers,seal bearers, heads ofarchivesand chiefscribes,among others.

Although the people of Meroë also had southern deities such asApedemak,the lion-son ofSekhmet(orBast,depending upon the region), they also continued worshipping ancient Egyptian gods that they had brought with them. Among these deities wereAmun,Tefnut,Horus,Isis,ThothandSatis,though to a lesser extent.

The collapse of their external trade with other Nile Valley states may be considered one of the prime causes of the decline of royal power and disintegration of the Meroitic state in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD.[6]

Language[edit]

TheMeroitic languagewas spoken in Meroë and the Sudan during the Meroitic period (attested from 300 BC). It became extinct around 400 AD. The language was written in two forms of theMeroitic Alpha bet:Meroitic Cursive, which was written with astylusand was used for general record-keeping; and Meroitic Hieroglyphic, which was carved in stone or used for royal or religious documents. It is not well understood due to the scarcity ofbilingualtexts. The earliest inscription in Meroitic writing dates from between 180 and 170 BC. These hieroglyphics were found engraved on the temple of QueenShanakdakhete.Meroitic Cursive is written horizontally, and reads from right to left like all Semitic orthographies.[30]

By the 3rd century BC, a new indigenousAlpha bet,theMeroitic,consisting of twenty-three letters, replaced Egyptian script. TheMeroitic scriptis anAlpha beticscript originally derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs, used to write the Meroitic language of the Kingdom of Kush. It was developed in the Napatan Period (c. 700 – 300 BC), and first appears in the 2nd century BC. For a time, it was also possibly used to write theNubian languageof the successor Nubian kingdoms.[31]

It is uncertain to which language family the Meroitic language is related. Kirsty Rowan suggests that Meroitic, like theEgyptian language,belongs to theAfro-Asiaticfamily. She bases this on its sound inventory andphonotactics,which, she proposes, are similar to those of the Afro-Asiatic languages and dissimilar from those of the Nilo-Saharan languages.[32][33]Claude Rilly, based on its syntax, morphology, and known vocabulary, proposes that Meroitic, like theNobiin language,instead belongs to theEastern Sudanicbranch of theNilo-Saharanfamily.[34][35][36]

Archaeology[edit]

The site of Meroë was brought to the knowledge of Europeans in 1821 by the French mineralogistFrédéric Cailliaud(1787–1869), who published an illustrated in-folio describing the ruins. His work included the first publication of the southernmost known Latin inscription.[b]

As Margoliouth notes in the 1911Encyclopedia Britannica,small scale excavations occurred in 1834, led byGiuseppe Ferlini,[2]who, as Margoliouth states, "discovered (or professed to discover) various antiquities, chiefly in the form of jewelry, now in the museums ofBerlinandMunich."[2]Margoliouth continues,

The ruins were examined in 1844 byC. R. Lepsius,who brought many plans, sketches and copies, besides actual antiquities, to Berlin. Further excavations were carried on byE. A. Wallis Budgein the years 1902 and 1905, the results of which are recorded in his work,The Egyptian Sudan: its History and Monuments…[38]Troops were furnished by SirReginald Wingate,governor of the Sudan, who made paths to and between the pyramids, and sank shafts, &c. It was found that the pyramids were regularly built over sepulchral chambers, containing the remains of bodies either burned or buried without being mummified. The most interesting objects found were the reliefs on the chapel walls, already described by Lepsius, and containing the names with representations of queens and some kings, with some chapters of theBook of the Dead;somesteleswith inscriptions in the Meroitic language, and some vessels of metal and earthenware. The best of thereliefswere taken down stone by stone in 1905, and set up partly in theBritish Museumand partly in the museum atKhartoum.In 1910, in consequence of a report byProfessor Archibald Sayce,excavations were commenced in the mounds of the town and the necropolis byJ[ohn] Garstangon behalf of theUniversity of Liverpool,and the ruins of a palace and several temples were discovered, built by the Meroite kings.[2]

-

Column and elephant - part of temple complex inMusawwarat es-Sufra

-

Roman Kiosk andApedemak TempleinNaqa

-

Colonnade of rams in front of Amun-Ra temple in Naqa

World Heritage listing[edit]

In June 2011, the Archeological Sites of Meroë were listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites.[3]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^The same episode, with slight variation, is also related inSefer Ha-Yashar,Tel-Aviv ca. 1965, pp. 192–195 (Hebrew) and inGedaliah ibn Yahya'sShalshelet Ha-Kabbalah,Jerusalem 1962, p. 22 (p. 31 in PDF) (Hebrew);Pseudo-Jonathan–the Aramaic Targum of pseudo-Jonathan ben Uziel(ed. Dr. M. Ginsburger), 2nd edition, Jerusalem 1974, p. 248.

- ^CILIII, 83.This inscription was subsequently published by Lepsius, who brought the stone back to Berlin. Although thought lost, it was recently rediscovered in theSkulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst of the Staatliche Museenin Berlin[37]

Citations[edit]

- ^"Meroë" in the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language(2020).

- ^abcdMargoliouth, David Samuel(1911)..InChisholm, Hugh(ed.).Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 172.

- ^ab"Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).Retrieved15 March2020.

- ^Elkhair, Osman; Ali, Imad-eldin."Ancient Meroe Site: Naqa and Musawwarat es-Sufra".Ancient Sudan–Kush.Ancientsudan.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2006.Retrieved6 September2012.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^abJosephus, Titus Flavius,Antiquities of the Jews,Book 2, Chapter 10, Section 2, Paragraphs 245–247 and 249, archived fromthe originalon 22 May 2020,retrieved19 February2017

- ^abcdefEdwards, David N. (1998). "Meroe and the Sudanic Kingdoms".The Journal of African History.39(2): 175–193.doi:10.1017/S0021853797007172.JSTOR183595.S2CID55376329.

- ^Gauthier, Henri (1926).Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques.Vol. 3. p.12.

- ^Török, László (1997).The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization.Handbuch der Orientalistik. Erste Abteilung, Nahe und der Mittlere Osten. Vol. 31. Leiden: Brill.ISBN90-04-10448-8.

- ^Festus Ugboaja Ohaegbulam (1 October 1990).Towards an understanding of the African experience from historical and contemporary perspectives.University Press of America. p.66.ISBN978-0-8191-7941-8.Retrieved17 March2011.

- ^Rilly, Claude (26 June 2016)."Meroitic".UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.1(1): 6.

- ^abcdDows Dunham, Notes on the History of Kush 850 B. C. – A. D. 350, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 50, No. 3 (July – September, 1946), pp. 378–388

- ^Herodotus(1949).Herodotus. Translated by J. Enoch Powell.Translated byEnoch Powell.Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 121–122.

- ^Connah, Graham (1987).African Civilizations: Precolonial Cities and States in Tropical Africa: An Archaeological Perspective.Cambridge University Press.p. 24.ISBN978-0-521-26666-6.

- ^George A. Reisner, The Pyramids of Meroë and the Candaces of Ethiopia, Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin, Vol. 21, No. 124 (Apr., 1923), pp. 11–27

- ^"Bronze head of Augustus".British Museum.1999. Archived fromthe originalon 10 February 2008.Retrieved14 June2008.

- ^abKirwan, L.P.(1957). "Rome beyond The Southern Egyptian Frontier".The Geographical Journal.123(1). London: Royal Geographical Society, with the Institute of British Geographers: 13–19.doi:10.2307/1790717.JSTOR1790717.

- ^"Nubia".BBC World Service.British Broadcasting Corporation.Retrieved6 September2012.

- ^Fisher, Greg (27 November 2019).Rome, Persia, and Arabia: Shaping the Middle East from Pompey to Muhammad.Routledge. p. 137.ISBN978-1-000-74090-5.

- ^abTabbernee, William (18 November 2014).Early Christianity in Contexts: An Exploration across Cultures and Continents.Baker Academic. p. 252.ISBN978-1-4412-4571-7.

- ^abAnfray, Francis; Caquot, André; Nautin, Pierre (1970)."Une nouvelle inscription grecque d'Ezana, roi d'Axoum".Journal des Savants.4(1): 266.doi:10.3406/jds.1970.1235.|quote=Moi, Ézana, roi des Axoumites, des Himyarites, de Reeidan, des Sabéens, de S[il]éel, de Kasô, des Bedja et de Tiamô, Bisi Alêne, fils de Elle-Amida et serviteur du Christ

- ^Valpy, Abraham John; Barker, Edmund Henry (28 February 2013).The Classical Journal.Cambridge University Press. p. 86.ISBN9781108057820.

- ^Gibbon, Edward (14 February 2016).THE HISTORY OF THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE (All 6 Volumes): From the Height of the Roman Empire, the Age of Trajan and the Antonines - to the Fall of Byzantium; Including a Review of the Crusades, and the State of Rome during the Middle Ages.e-artnow. p. Note 137.ISBN978-80-268-5034-2.

- ^Munro-Hay, Stuart C. (1991).Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity.Edinburgh University Press.pp. 79, 224.ISBN978-0-7486-0106-6.

- ^Stofferahn, Steven; Wood, Sarah (2016) [2003], Rauh, Nicholas K. (ed.),Lecture 30: Ancient Africa [CLCS 181: Classical World Civilizations](student lecture notes),West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University, School of Languages and Cultures,retrieved28 February2017

- ^Humphris, Jane; Charlton, Michael F.; Keen, Jake; Sauder, Lee; Alshishani, Fareed (2018)."Iron Smelting in Sudan: Experimental Archaeology at The Royal City of Meroe".Journal of Field Archaeology.43(5): 399.doi:10.1080/00934690.2018.1479085.ISSN0093-4690.

- ^abHakem, A.A.; Hrbek, I.; Vercoutter, J. (1981)."The Civilization of Napata and Meroe".In Mokhtar, G. (ed.).Ancient Civilizations of Africa.General History of Africa. Vol. II. Paris/London/Berkeley, CA: UNESCO/Heinemann/University of California Press. pp. 298–325, esp. 312f.ISBN0435948059– viaUNESCO.

- ^Roland Oliver;Brian M. Fagan(1975).Africa in the Iron Age.Cambridge University Press.p. 6.ISBN0521099005.

the urban wealth of Meroe came from its hunting, mining, and trading activities […] ivory, slaves, rare skins, ostrich feathers, gold, copper, and ebony

- ^Berney, K. A.; Ring, Trudy, eds. (1996).International Dictionary of Historic Places.Vol. 4: Middle East and Africa. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 506.ISBN978-1-884964-03-9.

- ^Adams, William Yewdale (1977).Nubia: Corridor to Africa.Princeton University Press.p. 302.ISBN978-0-691-09370-3.

- ^Fischer, Steven Roger (2004).History of Writing.Reaktion Books. pp. 133–134.ISBN1861895887.

- ^""Meroe: Writing",Digital Egypt,University College, London ".Digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk.Retrieved6 September2012.

- ^Rowan, Kirsty (2011)."Meroitic Consonant and Vowel Patterning".Lingua Aegytia.19(19): 115–124.

- ^Rowan, Kirsty (2006)."Meroitic – An Afroasiatic Language?"(PDF).SOASWorking Papers in Linguistics(14): 169–206. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 December 2015.Retrieved24 December2014.

- ^Rilly, Claude; de Voogt, Alex (2012).The Meroitic Language and Writing System.Cambridge University Press. p. 6.ISBN978-1-107-00866-3.

- ^Rilly, Claude (March 2004)."The Linguistic Position of Meroitic"(PDF).ARKAMANI: Sudan Electronic Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 23 September 2015.Retrieved24 December2014.

- ^Rilly, Claude (June 2016)."Meroitic".In Stauder-Porchet, Julie; Stauder, Andréas; Wendrich, Willeke (eds.).UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

- ^Łajtar, Adam; van der Vliet, Jacques (2006). "Rome-Meroe-Berlin. The Southernmost Latin Inscription Rediscovered ('CIL' III 83)".Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik.157(157): 193–198.JSTOR20191127.

- ^Budge, E. A. Wallis(1907).The Egyptian Sudan, its history and monuments.Vol. 2 (1st ed.). London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.

Further reading[edit]

- Bianchi, Steven (1994).The Nubians: People of the ancient Nile.Brookfield, Conn.: Millbrook Press.ISBN1-56294-356-1.

- Davidson, Basil (1966).Africa, History of A Continent.London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 41–58.

- Shinnie, P. L. (1967).Meroe, a civilization of Sudan.Ancient People and Places. Vol. 55. London/New York: Thames and Hudson.

External links[edit]

Media related toMeroëat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toMeroëat Wikimedia Commons- LearningSites – Gebel Barkal

- UNESCO World Heritage – Gebel Barkal and the Sites of the Napatan Region

- Nubia Museum – Meroitic Empire

- Voyage au pays des pharaons noirsTravel in Sudan and notes on Nubian history(in French)

- Labelled map of the pyramids at Meroe

- Sudan's forgotten pyramids – BBC News

- Pictures of Meroë– An online slide show as part of a detailed travelogue (in German)