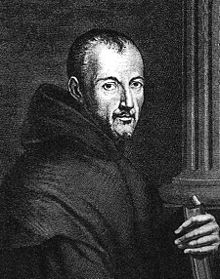

Marin Mersenne

Marin Mersenne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 September 1588 |

| Died | 1 September 1648(aged 59) Paris, France |

| Other names | Marinus Mersennus |

| Known for | Mersenne primes Mersenne's conjecture Mersenne's laws Acoustics |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics,physics |

Marin Mersenne,OM(also known asMarinus Mersennusorle PèreMersenne;French:[maʁɛ̃mɛʁsɛn];8 September 1588 – 1 September 1648) was a Frenchpolymathwhose works touched a wide variety of fields. He is perhaps best known today among mathematicians forMersenne primenumbers, those written in the formMn= 2n− 1for someintegern.He also developedMersenne's laws,which describe the harmonics of a vibrating string (such as may be found onguitarsandpianos), and his seminal work onmusic theory,Harmonie universelle,for which he is referred to as the "father ofacoustics".[1][2]Mersenne, an ordainedCatholic priest,had many contacts in the scientific world and has been called "the center of the world of science and mathematics during the first half of the 1600s"[3]and, because of his ability to make connections between people and ideas, "the post-box of Europe".[4]He was also a member of the asceticalMinimreligious order and wrote and lectured ontheologyandphilosophy.

Life

[edit]Mersenne was born of Jeanne Moulière, wife of Julien Mersenne, peasants who lived nearOizé,County of Maine(present-daySarthe,France).[5]He was educated atLe Mansand at theJesuit College of La Flèche.On 17 July 1611, he joined theMinim Friarsand, after studying theology andHebrewin Paris, was ordained a priest in 1613.

Between 1614 and 1618, he taught theology and philosophy atNevers,but he returned to Paris and settled at the convent ofL'Annonciadein 1620. There he studied mathematics and music and met with other kindred spirits such asRené Descartes,Étienne Pascal,Pierre Petit,Gilles de Roberval,Thomas Hobbes,andNicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc.He corresponded withGiovanni Doni,Jacques Alexandre Le Tenneur,Constantijn Huygens,Galileo Galilei,and other scholars in Italy, England and theDutch Republic.He was a staunch defender of Galileo, assisting him in translations of some of his mechanical works.

For four years, Mersenne devoted himself entirely to philosophic and theological writing, and publishedQuaestiones celeberrimae in Genesim(Celebrated Questions on the Book of Genesis) (1623);L'Impieté des déistes(The Impiety of theDeists) (1624);La Vérité des sciences(Truth of the Sciences Against the Sceptics,1624). It is sometimes incorrectly stated that he was aJesuit.He was educated by Jesuits, but he never joined theSociety of Jesus.He taught theology and philosophy at Nevers and Paris.

In 1635 he set up the informalAcadémie Parisienne(Academia Parisiensis), which had nearly 140 correspondents, including astronomers and philosophers as well as mathematicians, and was the precursor of theAcadémie des sciencesestablished byJean-Baptiste Colbertin 1666.[a]He was not afraid to cause disputes among his learned friends in order to compare their views, notable among which were disputes between Descartes,Pierre de Fermat,andJean de Beaugrand.[6]Peter L. Bernstein,in his bookAgainst the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk,wrote, "The Académie des Sciences in Paris and the Royal Society in London, which were founded about twenty years after Mersenne's death, were direct descendants of Mersenne's activities."[7]

In 1635 Mersenne met withTommaso Campanellabut concluded that he could "teach nothing in the sciences... but still he has a good memory and a fertile imagination." Mersenne asked if Descartes wanted Campanella to come to Holland to meet him, but Descartes declined. He visited Italy fifteen times, in 1640, 1641 and 1645. In 1643–1644 Mersenne also corresponded with the German SocinianMarcin Ruarconcerning the Copernican ideas ofPierre Gassendi,finding Ruar already a supporter of Gassendi's position.[8]Among his correspondents were Descartes, Galileo, Roberval,Pascal,Beeckmanand other scientists.

He died on 1 September 1648 of complications arising from alung abscess.

Work

[edit]Quaestiones celeberrimae in Genesimwas written as a commentary on theBook of Genesisand comprises uneven sections headed by verses from the first three chapters of that book. At first sight the book appears to be a collection of treatises on various miscellaneous topics. However Robert Lenoble has shown[9]that the principle of unity in the work is a polemic againstmagicalanddivinatoryarts,cabalism,andanimisticandpantheisticphilosophies.

Mersenne was concerned with the teachings of some Italiannaturaliststhat all things happened naturally and determined astrologically; for example, thenomological determinismofLucilio Vanini( "God acts on sublunary beings (humans) using the sky as a tool" ), andGerolamo Cardano's idea that martyrs and heretic were compelled to self-harm by the stars;[10]Historian of science William Ashworth[11]explains "Miracles, for example, were endangered by the naturalists, because in a world filled with sympathies and occult forces—with what Lenoble calls a" spontanéité indéfinie "—anything could happen naturally"[12]: 138

Mersenne mentionsMartin Del Rio'sInvestigations into Magicand criticisesMarsilio Ficinofor claiming power for images and characters. He condemns astral magic andastrologyand theanima mundi,a concept popular amongstRenaissanceneo-platonists.Whilst allowing for a mystical interpretation of the Cabala, he wholeheartedly condemned its magical application, particularlyangelology.He also criticisesPico della Mirandola,Cornelius Agrippa,Francesco GiorgioandRobert Fludd,his main target.

Harmonie universelleis perhaps Mersenne's most influential work. It is one of the earliest comprehensive works on music theory, touching on a wide range of musical concepts, and especially the mathematical relationships involved in music. The work contains the earliest formulation of what has become known asMersenne's laws,which describe the frequency of oscillation of a stretched string. This frequency is:

- Inversely proportional to the length of the string (this was known to the ancients; it is usually credited toPythagoras)

- Proportional to the square root of the stretching force, and

- Inversely proportional to the square root of the mass per unit length.

The formula for the lowest frequency is

wherefis the frequency [Hz],Lis the length [m],Fis the force [N] and μ is the mass per unit length [kg/m].

In this book, Mersenne also introduced several innovative concepts that can be considered the basis of modern reflecting telescopes:

- Much earlier thanLaurent Cassegrain,he found the fundamental arrangement of the two-mirror telescope combination, a concave primary mirror associated with a convex secondary mirror, and discovered the telephoto effect that is critical in reflecting telescopes, although he was far from having understood all the implications of that discovery.

- Mersenne invented theafocaltelescope and the beam compressor that is useful in many multiple-mirror telescope designs.[13]

- He recognized also that he could correct thespherical aberrationof the telescope by using aspherical mirrors and that in the particular case of the afocal arrangement he could do this correction by using two parabolic mirrors, though ahyperboloidis required.[14]

Because of criticism that he encountered, especially from Descartes, Mersenne made no attempt to build a telescope of his own.

Mersenne is also remembered today thanks to his association with theMersenne primes.TheMersenne Twister,named for Mersenne primes, is frequently used in computer engineering and in related fields such as cryptography.

However, Mersenne was not primarily a mathematician; he wrote aboutmusic theoryand other subjects. He edited works ofEuclid,Apollonius,Archimedes,and otherGreek mathematicians.But perhaps his most important contribution to the advance of learning was his extensive correspondence (inLatin) with mathematicians and other scientists in many countries. At a time when thescientific journalhad not yet come into being, Mersenne was the centre of a network for exchange of information.

It has been argued that Mersenne used his lack of mathematical specialty, his ties to the print world, his legal acumen, and his friendship with the French mathematician and philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) to manifest his international network of mathematicians.[15]

Mersenne's philosophical works are characterized by wide scholarship and the narrowest theological orthodoxy. His greatest service to philosophy was his enthusiastic defence of Descartes, whose agent he was in Paris and whom he visited in exile in theNetherlands.He submitted to various eminent Parisian thinkers a manuscript copy of theMeditations on First Philosophy,and defended its orthodoxy against numerous clerical critics.

In later life, he gave up speculative thought and turned to scientific research, especially in mathematics, physics and astronomy. In this connection, his best known work isHarmonie universelleof 1636, dealing with thetheory of musicandmusical instruments.It is regarded as a source of information on 17th-century music, especially French music and musicians, to rival even the works ofPietro Cerone.

One of his many contributions tomusical tuningtheory was the suggestion of

as theratiofor anequally-temperedsemitone(). It was more accurate (0.44centssharp) thanVincenzo Galilei's 18/17 (1.05 cents flat), and could be constructed usingstraightedge and compass.Mersenne's description in the 1636Harmonie universelleof the first absolute determination of the frequency of an audible tone (at 84 Hz) implies that he had already demonstrated that the absolute-frequency ratio of two vibrating strings, radiating a musical tone and itsoctave,is 1: 2. The perceived harmony (consonance) of two such notes would be explained if the ratio of the air oscillation frequencies is also 1: 2, which in turn is consistent with the source-air-motion-frequency-equivalence hypothesis.

He also performed extensive experiments to determine the acceleration of falling objects by comparing them with the swing ofpendulums,reported in hisCogitata Physico-Mathematicain 1644. He was the first to measure the length of theseconds pendulum,that is a pendulum whose swing takes one second, and the first to observe that a pendulum's swings are notisochronousas Galileo thought, but that large swings take longer than small swings.[16]

Battles with occult and mystical thinkers

[edit]Two German pamphlets that circulated around Europe in 1614–15,Fama fraternitatisandConfessio Fraternitatis,claimed to be manifestos of a highly select, secret society of alchemists and sages called the Brotherhood ofRosicrucians.The books were allegories, but were obviously written by a small group who were reasonably knowledgeable about the sciences of the day,[citation needed]and their main theme was to promote educational reform (they were anti-Aristotelian). These pamphlets also promoted an occult view of science[citation needed]containing elements ofParacelsian philosophy,neo-Platonism,Christian CabalaandHermeticism.In effect, they sought to establish a new form of scientific religion with some pre-Christian elements.[citation needed]

Mersenne led the fight against acceptance of these ideas, particularly those of Rosicrucian promoterRobert Fludd,who had a lifelong battle of words withJohannes Kepler.Fludd responded withSophia cum moria certamen(1626), wherein he discusses his involvement with theRosicrucians.The anonymousSummum bonum(1629), another critique of Mersenne, is a Rosicrucian-themed text. The cabalistJacques Gaffareljoined Fludd's side, whilePierre Gassendidefended Mersenne.

The Rosicrucian ideas were defended by many prominent men of learning, and some members of the European scholarly community boosted their own prestige by claiming to be among the selected members of the Brotherhood.[citation needed]However, it is now generally agreed among historians that there is no evidence that an order of Rosicrucians existed at the time, with later Rosicrucian Orders drawing on the name, with no relation to the writers of the Rosicrucian Manifestoes.[17]

During the mid-1630s Mersenne gave up the search for physical causes in theAristoteliansense (rejecting the idea ofessences,which were still favoured by thescholastic philosophers) and taught that true physics could be only a descriptive science of motions (Mécanisme), which was the direction set byGalileo Galilei.Mersenne had been a regular correspondent with Galileo and had extended the work on vibrating strings originally developed by his father,Vincenzo Galilei.[18]

Music

[edit]Anairattributed to Mersenne was used byOttorino Respighiin his second suite ofAncient Airs and Dances

List of works

[edit]

- Euclidis elementorum libri,etc. (Paris, 1626)

- Les Mécaniques de Galilée(Paris, 1634)

- Questions inouies ou récréation des savants(1634)

- Questions théologiques, physiques,etc. (1634)

- Harmonie universelleFirst edition onlinefromGallica(Paris, 1636). Translation to English by Roger E. Chapman (The Hague, 1957)

- Nouvelles découvertes de Galilée(1639)

- Cogitata physico-mathematica(1644)

- Universae geometriae synopsis(1644)

- Tractatus mechanicus theoricus et practicus(in Latin). Paris: Antoine Bertier. 1644.

See also

[edit]- Cassegrain reflector

- Catalan–Mersenne number/Catalan's Mersenne conjecture

- Cycloid

- Equal temperament

- Euler's factorization method

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Renaissance skepticism

- Seconds pendulum

References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^For a summary description of all members of the Academia Parisiensis from its creation until 1648, seeDe la Croix & Duchêne 2021,pp. 7–12

Citations

[edit]- ^Bohn, Dennis A. (1988)."Environmental Effects on the Speed of Sound"(PDF).Journal of the Audio Engineering Society.36(4): 223–231. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 1 August 2014.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^Simmons, George F. (1992/2007).Calculus Gems: Brief Lives and Memorable Mathematics,p. 94.MAA.ISBN9780883855614.

- ^Bernstein, Peter L. (1996).Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk.John Wiley & Sons. p.59.ISBN978-0-471-12104-6.

- ^Connolly, Mickey; Motroni, Jim; McDonald, Richard (25 October 2016).The Vitality Imperative: How Connected Leaders and Their Teams Achieve More with Less Time, Money, and Stress.RDA Press.ISBN9781937832926.

- ^Hauréau, Barthélemy (1852). A. Lanier (ed.).Histoire littéraire du Maine(in French). Vol. 1. p. 321.

- ^ Sergescu, Pierre (1948)."Mersenne l'Animateur".Revue de l'Histoire des Sciences et Leur Applications.2(2–1): 5–12.doi:10.3406/rhs.1948.2726.

- ^Bernstein 1996,p. 59.

- ^Murr, Sylvia, ed. (1997).Gassendi et l'Europe(in French). Paris: Vrin.ISBN978-2-7116-1306-9.

- ^Lenoble, Robert (1943).Mersenne ou la naissance du mécanisme.Paris: Vrin.

- ^Regier, Jonathan (2019)."Reading Cardano with the Roman Inquisition: Astrology, Celestial Physics, and the Force of Heresy"(PDF).Isis.110(4): 661–679.doi:10.1086/706783.hdl:1854/LU-8608904.S2CID201272821.

- ^"William B Ashworth Jr".scholar.google.

- ^"Italian naturalism was considered dangerous to religion because it confused the natural with the supernatural and physics with metaphysics; essentially, it eliminated the boundaries between science and faith."Ashworth, William B. (31 December 1986). "5. Catholicism and Early Modern Science".God and Nature:136–166.doi:10.1525/9780520908031-007.ISBN978-0-520-90803-1.

- ^Wilson, Todd (2007),Reflecting Telescope Optics I: Basic Design Theory and its Historical Development,Springer, p. 4,ISBN9783540765813.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark(2003).Mirror Mirror: A History of the Human Love Affair with Reflection.Basic Books. pp. 88–89.ISBN0786729902.

- ^Grosslight, Justin (2013). "Small Skills, Big Networks: Marin Mersenne as Mathematical Intelligencer".History of Science.51(3): 337–374.Bibcode:2013HisSc..51..337G.doi:10.1177/007327531305100304.S2CID143320489.

- ^Koyre, Alexander (1992).Metaphysics and Measurement.Taylor & Francis. p. 100.ISBN2-88124-575-7.

- ^Debus, A.G. (2013).The Chemical Philosophy.Dover Books on Chemistry. Dover Publications.ISBN978-0-486-15021-5.

- ^Heilbron, J. L. (1979).Electricity in the 17th and 18th Centuries: A Study of Early Modern Physics.University of California Press.ISBN9780520034785.

General and cited sources

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911). "Mersenne, Marin".Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- De la Croix, David;Duchêne, Julie (2021)."Scholars and Literati at the" Mersenne "Academy (1635–1648)".Repertorium Eruditorum Totius Europae.2.Universite Catholique de Louvain: 7–12.doi:10.14428/rete.v2i0/mersenne.ISSN2736-4119.

Further reading

[edit]- Baillet, Adrien(1691).Vie de Descartes.

- Dear, Peter Robert (1988).Mersenne and the Learning of the SchoolsIthaca: Cornell University Press.

- Gehring, F. (1922) “Mersennus, Marin (le Père Mersenne)”.Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians(ed. J. A. Fuller Maitland).

- Grosslight, Justin (2013). "Small Skills, Big Networks: Marin Mersenne as Mathematical Intelligencer".History of Science51:337–374.

- Moreau, Roger (2012).Marin Mersenne et la naissance de l'esprit scientifique.Editions Anagrammes, Perros Guirec. (ISBN978-2-84719-089-2).

- Poté, J. (1816).Éloge de Mersenne.Le Mans.

External links

[edit]- IMSLPTraité de l'Harmonie Universelle.

- The Correspondence of Marin MersenneinEMLO

- "Marin Mersenne"entry by Philippe Hamou in theStanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,June 13, 2022

- O'Connor, John J.;Robertson, Edmund F.,"Marin Mersenne",MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive,University of St Andrews

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913)..Catholic Encyclopedia.New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Marin Mersenne",Mathematics Genealogy Project.

- Minimospedia "Marin Mersenne"especially for bibliography

- Scholars and Literati at the "Mersenne" Academy (1635–1800),inRepertorium Eruditorum Totius Europae/RETE.

- Documentaries

- Marin Mersenne—The Birth of Modern Geometry(UKOpen UniversityTV documentary made in 1986 and transmitted onBBC2)

- 1588 births

- 1648 deaths

- 17th-century French male writers

- 17th-century French mathematicians

- 17th-century French people

- Catholic clergy scientists

- Deaths from lung abscess

- French male non-fiction writers

- French mathematicians

- French music theorists

- 17th-century French Roman Catholic priests

- Minims (religious order)

- French number theorists

- People from Sarthe

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{4}]{\frac {2}{3-{\sqrt {2}}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/afa67e96081b9370c2aa1f4f41e02d7bc412e931)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bc835f27425fb3140e1f75a5faa35b1e8b9efc35)