Animal

| Animals Temporal range:Cryogenian– present,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Amorphea |

| Clade: | Obazoa |

| (unranked): | Opisthokonta |

| (unranked): | Holozoa |

| (unranked): | Filozoa |

| Clade: | Choanozoa |

| Kingdom: | Animalia Linnaeus,1758 |

| Subdivisions | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Animalsaremulticellular,eukaryoticorganismsin thebiological kingdomAnimalia(/ˌænɪˈmeɪliə/[4]). With few exceptions, animalsconsume organic material,breathe oxygen,havemyocytesand areable to move,canreproduce sexually,and grow from a hollow sphere of cells, theblastula,duringembryonic development.Animals form aclade,meaning that they arose from a single common ancestor.

Over 1.5 millionlivinganimalspecieshave beendescribed,of which around 1.05 million areinsects,over 85,000 aremolluscs,and around 65,000 arevertebrates.It has been estimated there are as many as 7.77 million animal species on Earth. Animal body lengths range from 8.5 μm (0.00033 in) to 33.6 m (110 ft). They have complexecologiesandinteractionswith each other and their environments, forming intricatefood webs.The scientific study of animals is known aszoology,and the study of animal behaviors is known asethology.

Most living animal species belong to the infrakingdomBilateria,a highly proliferativecladewhose members have abilaterally symmetricbody plan.The vast majority belong to two largesuperphyla:theprotostomes,which includes organisms such as thearthropods,molluscs,flatworms,annelidsandnematodes;and thedeuterostomes,which include theechinoderms,hemichordatesandchordates,the latter of which contains the vertebrates. The simpleXenacoelomorphahave an uncertain position within Bilateria.

Animals first appear in the fossil record in the lateCryogenianperiod, and diversified in the subsequentEdiacaran.Earlier evidence of animals is still controversial; thesponge-like organismOtaviahas been dated back to theTonianperiod at the start of theNeoproterozoic,but its identity as an animal is heavily contested.[5]Nearly all modern animal phyla became clearly established in the fossil record asmarine speciesduring theCambrian explosion,which began around 539million years ago(Mya), and mostclassesduring theOrdovician radiation485.4 Mya. 6,331 groups ofgenescommon to all living animals have been identified; these may have arisen from a singlecommon ancestorthat lived about 650 Mya during theCryogenianperiod.

Historically,Aristotledivided animalsinto those with blood and those without.Carl Linnaeuscreated the first hierarchicalbiological classificationfor animals in 1758 with hisSystema Naturae,whichJean-Baptiste Lamarckexpanded into 14 phyla by 1809. In 1874,Ernst Haeckeldivided the animal kingdom into the multicellularMetazoa(nowsynonymouswith Animalia) and theProtozoa,single-celled organisms no longer considered animals. In modern times, the biological classification of animals relies on advanced techniques, such asmolecular phylogenetics,which are effective at demonstrating theevolutionaryrelationships betweentaxa.

Humansmakeuse ofmany other animal species forfood(includingmeat,eggs,anddairy products), formaterials(such asleather,fur,andwool), aspetsand asworking animalsfortransportation,andservices.Dogs,the firstdomesticatedanimal, have been usedin hunting,in securityandin warfare,as havehorses,pigeonsandbirds of prey;while otherterrestrialandaquatic animalsarehuntedfor sports, trophies or profits. Non-human animals are also an importantculturalelement ofhuman evolution,having appeared incave artsandtotemssince the earliest times, and are frequently featured inmythology,religion,arts,literature,heraldry,politics,andsports.

Etymology

The wordanimalcomes from the Latin nounanimalof the same meaning, which is itself derived from Latinanimalis'having breath or soul'.[6]The biological definition includes all members of the kingdom Animalia.[7]In colloquial usage, the termanimalis often used to refer only to nonhuman animals.[8][9][10][11]The termmetazoais derived from Ancient Greek μετα (meta) 'after' (in biology, the prefixmeta-stands for 'later') and ζῷᾰ (zōia) 'animals', plural of ζῷονzōion'animal'.[12][13]

Characteristics

Animals have several characteristics that set them apart from other living things. Animals areeukaryoticandmulticellular.[14]Unlike plants andalgae,whichproduce their own nutrients,[15]animals areheterotrophic,[16][17]feeding on organic material and digesting it internally.[18]With very few exceptions, animalsrespire aerobically.[a][20]All animals aremotile[21](able to spontaneously move their bodies) during at least part of theirlife cycle,but some animals, such assponges,corals,mussels,andbarnacles,later becomesessile.Theblastulais a stage inembryonic developmentthat is unique to animals, allowingcells to be differentiatedinto specialised tissues and organs.[22]

Structure

All animals are composed of cells, surrounded by a characteristicextracellular matrixcomposed ofcollagenand elasticglycoproteins.[23]During development, the animal extracellular matrix forms a relatively flexible framework upon which cells can move about and be reorganised, making the formation of complex structures possible. This may be calcified, forming structures such asshells,bones,andspicules.[24]In contrast, the cells of other multicellular organisms (primarily algae, plants, andfungi) are held in place by cell walls, and so develop by progressive growth.[25]Animal cells uniquely possess thecell junctionscalledtight junctions,gap junctions,anddesmosomes.[26]

With few exceptions—in particular, the sponges andplacozoans—animal bodies are differentiated intotissues.[27]These includemuscles,which enable locomotion, andnerve tissues,which transmit signals and coordinate the body. Typically, there is also an internaldigestivechamber with either one opening (in Ctenophora, Cnidaria, and flatworms) or two openings (in most bilaterians).[28]

Reproduction and development

Nearly all animals make use of some form of sexual reproduction.[29]They producehaploidgametesbymeiosis;the smaller, motile gametes arespermatozoaand the larger, non-motile gametes areova.[30]These fuse to formzygotes,[31]which develop viamitosisinto a hollow sphere, called a blastula. In sponges, blastula larvae swim to a new location, attach to the seabed, and develop into a new sponge.[32]In most other groups, the blastula undergoes more complicated rearrangement.[33]It firstinvaginatesto form agastrulawith a digestive chamber and two separategerm layers,an externalectodermand an internalendoderm.[34]In most cases, a third germ layer, themesoderm,also develops between them.[35]These germ layers then differentiate to form tissues and organs.[36]

Repeated instances ofmating with a close relativeduring sexual reproduction generally leads toinbreeding depressionwithin a population due to the increased prevalence of harmfulrecessivetraits.[37][38]Animals have evolved numerous mechanisms foravoiding close inbreeding.[39]

Some animals are capable ofasexual reproduction,which often results in a genetic clone of the parent. This may take place throughfragmentation;budding,such as inHydraand othercnidarians;orparthenogenesis,where fertile eggs are produced withoutmating,such as inaphids.[40][41]

Ecology

Animals are categorised into ecological groups depending on theirtrophic levelsandhow they consume organic material.Such groupings includecarnivores(further divided into subcategories such aspiscivores,insectivores,ovivores,etc.),herbivores(subcategorized intofolivores,graminivores,frugivores,granivores,nectarivores,algivores,etc.),omnivores,fungivores,scavengers/detritivores,[42]andparasites.[43]Interactionsbetween animals of eachbiomeform complexfood webswithin thatecosystem.In carnivorous or omnivorous species,predationis aconsumer–resource interactionwhere the predator feeds on another organism, itsprey,[44]who often evolvesanti-predator adaptationsto avoid being fed upon.Selective pressuresimposed on one another lead to anevolutionary arms racebetween predator and prey, resulting in various antagonistic/competitivecoevolutions.[45][46]Almost all multicellular predators are animals.[47]Someconsumersuse multiple methods; for example, inparasitoid wasps,the larvae feed on the hosts' living tissues, killing them in the process,[48]but the adults primarily consume nectar from flowers.[49]Other animals may have very specificfeeding behaviours,such ashawksbill sea turtleswhich mainlyeat sponges.[50]

Most animals rely onbiomassandbioenergyproduced byplantsandphytoplanktons(collectively calledproducers) throughphotosynthesis.Herbivores, asprimary consumers,eat the plant material directly to digest and absorb the nutrients, while carnivores and other animals on highertrophic levelsindirectly acquire the nutrients by eating the herbivores or other animals that have eaten the herbivores. Animals oxidizecarbohydrates,lipids,proteinsand other biomolecules, which allows the animal to grow and to sustainbasal metabolismand fuel other biological processes such aslocomotion.[51][52][53]Somebenthicanimals living close tohydrothermal ventsandcold seepson the darksea floorconsume organic matter produced throughchemosynthesis(viaoxidizinginorganic compoundssuch ashydrogen sulfide) byarchaeaandbacteria.[54]

Animals evolved in the sea. Lineages of arthropods colonised land around the same time asland plants,probably between 510 and 471 million years ago during theLate Cambrianor EarlyOrdovician.[55]Vertebratessuch as thelobe-finned fishTiktaalikstarted to move on to land in the lateDevonian,about 375 million years ago.[56][57]Animals occupy virtually all of earth'shabitatsand microhabitats, withfaunasadapted to salt water, hydrothermal vents, fresh water, hot springs, swamps, forests, pastures, deserts, air, and the interiors of other organisms.[58]Animals are however not particularlyheat tolerant;very few of them can survive at constant temperatures above 50 °C (122 °F)[59]or in the most extreme cold deserts of continentalAntarctica.[60]

Diversity

Size

Theblue whale(Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest animal that has ever lived, weighing up to 190tonnesand measuring up to 33.6 metres (110 ft) long.[61][62][63]The largest extant terrestrial animal is theAfrican bush elephant(Loxodonta africana), weighing up to 12.25 tonnes[61]and measuring up to 10.67 metres (35.0 ft) long.[61]The largest terrestrial animals that ever lived weretitanosaursauropod dinosaurssuch asArgentinosaurus,which may have weighed as much as 73 tonnes, andSupersauruswhich may have reached 39 meters.[64][65]Several animals are microscopic; someMyxozoa(obligate parasiteswithin the Cnidaria) never grow larger than 20μm,[66]and one of the smallest species (Myxobolus shekel) is no more than 8.5 μm when fully grown.[67]

Numbers and habitats of major phyla

The following table lists estimated numbers of described extant species for the major animal phyla,[68]along with their principal habitats (terrestrial, fresh water,[69]and marine),[70]and free-living or parasitic ways of life.[71]Species estimates shown here are based on numbers described scientifically; much larger estimates have been calculated based on various means of prediction, and these can vary wildly. For instance, around 25,000–27,000 species of nematodes have been described, while published estimates of the total number of nematode species include 10,000–20,000; 500,000; 10 million; and 100 million.[72]Using patterns within thetaxonomichierarchy, the total number of animal species—including those not yet described—was calculated to be about 7.77 million in 2011.[73][74][b]

| Phylum | Example | Described species | Land | Sea | Freshwater | Free-living | Parasitic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthropoda |

|

1,257,000[68] | Yes 1,000,000 (insects)[76] |

Yes >40,000 (Malac- ostraca)[77] |

Yes 94,000[69] | Yes[70] | Yes >45,000[c][71] |

| Mollusca |

|

85,000[68] 107,000[78] |

Yes 35,000[78] | Yes 60,000[78] | Yes 5,000[69] 12,000[78] |

Yes[70] | Yes >5,600[71] |

| Chordata |

|

>70,000[68][79] | Yes 23,000[80] | Yes 13,000[80] | Yes 18,000[69] 9,000[80] |

Yes | Yes 40 (catfish)[81][71] |

| Platyhelminthes |

|

29,500[68] | Yes[82] | Yes[70] | Yes 1,300[69] | Yes[70] 3,000–6,500[83] |

Yes >40,000[71] 4,000–25,000[83] |

| Nematoda |

|

25,000[68] | Yes (soil)[70] | Yes 4,000[72] | Yes 2,000[69] | Yes 11,000[72] |

Yes 14,000[72] |

| Annelida |

|

17,000[68] | Yes (soil)[70] | Yes[70] | Yes 1,750[69] | Yes | Yes 400[71] |

| Cnidaria |

|

16,000[68] | Yes[70] | Yes (few)[70] | Yes[70] | Yes >1,350 (Myxozoa)[71] | |

| Porifera |

|

10,800[68] | Yes[70] | 200–300[69] | Yes | Yes[84] | |

| Echinodermata |

|

7,500[68] | Yes 7,500[68] | Yes[70] | |||

| Bryozoa |

|

6,000[68] | Yes[70] | Yes 60–80[69] | Yes | ||

| Rotifera |

|

2,000[68] | Yes >400[85] | Yes 2,000[69] | Yes | ||

| Nemertea |

|

1,350[86][87] | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Tardigrada |

|

1,335[68] | Yes[88] (moist plants) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | |

Evolutionary origin

Evidence of animals is found as long ago as theCryogenianperiod.24-Isopropylcholestane(24-ipc) has been found in rocks from roughly 650 million years ago; it is only produced by sponges andpelagophytealgae. Its likely origin is from sponges based onmolecular clockestimates for the origin of 24-ipc production in both groups. Analyses of pelagophyte algae consistently recover aPhanerozoicorigin, while analyses of sponges recover aNeoproterozoicorigin, consistent with the appearance of 24-ipc in the fossil record.[89][90]

The first body fossils of animals appear in theEdiacaran,represented by forms such asCharniaandSpriggina.It had long been doubted whether these fossils truly represented animals,[91][92][93]but the discovery of the animal lipidcholesterolin fossils ofDickinsoniaestablishes their nature.[94]Animals are thought to have originated under low-oxygen conditions, suggesting that they were capable of living entirely byanaerobic respiration,but as they became specialized for aerobic metabolism they became fully dependent on oxygen in their environments.[95]

Many animal phyla first appear in thefossilrecord during theCambrian explosion,starting about 539 million years ago, in beds such as theBurgess shale.[96]Extant phyla in these rocks includemolluscs,brachiopods,onychophorans,tardigrades,arthropods,echinodermsandhemichordates,along with numerous now-extinct forms such as thepredatoryAnomalocaris.The apparent suddenness of the event may however be an artifact of the fossil record, rather than showing that all these animals appeared simultaneously.[97][98][99][100]That view is supported by the discovery ofAuroralumina attenboroughii,the earliest known Ediacaran crown-group cnidarian (557–562 mya, some 20 million years before the Cambrian explosion) fromCharnwood Forest,England. It is thought to be one of the earliestpredators,catching small prey with itsnematocystsas modern cnidarians do.[101]

Some palaeontologists have suggested that animals appeared much earlier than the Cambrian explosion, possibly as early as 1 billion years ago.[102]Early fossils that might represent animals appear for example in the 665-million-year-old rocks of theTrezona FormationofSouth Australia.These fossils are interpreted as most probably being earlysponges.[103] Trace fossilssuch as tracks and burrows found in theTonianperiod (from 1 gya) may indicate the presence oftriploblasticworm-like animals, roughly as large (about 5 mm wide) and complex as earthworms.[104]However, similar tracks are produced by the giant single-celled protistGromia sphaerica,so the Tonian trace fossils may not indicate early animal evolution.[105][106]Around the same time, the layered mats ofmicroorganismscalledstromatolitesdecreased in diversity, perhaps due to grazing by newly evolved animals.[107]Objects such as sediment-filled tubes that resemble trace fossils of the burrows of wormlike animals have been found in 1.2 gya rocks in North America, in 1.5 gya rocks in Australia and North America, and in 1.7 gya rocks in Australia. Their interpretation as having an animal origin is disputed, as they might be water-escape or other structures.[108][109]

-

Dickinsonia costatafrom theEdiacaran biota(c. 635–542 mya) is one of the earliest animal species known.[94]

-

Auroralumina attenboroughii,an Ediacaran predator (c. 560 mya)[101]

-

Anomalocaris canadensisis one of the many animal species that emerged in theCambrian explosion,starting some 539 mya, and found in the fossil beds of theBurgess shale.

Phylogeny

External phylogeny

Animals aremonophyletic,meaning they are derived from a common ancestor. Animals are the sister group to thechoanoflagellates,with which they form theChoanozoa.[110] The dates on thephylogenetic treeindicate approximately how many millions of years ago (mya) the lineages split.[111][112][113][114][115]

Ros-Rocher and colleagues (2021) trace the origins of animals to unicellular ancestors, providing the external phylogeny shown in the cladogram. Uncertainty of relationships is indicated with dashed lines.[116]

| Opisthokonta |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1300 mya |

Internal phylogeny

The most basal animals, thePorifera,Ctenophora,Cnidaria,andPlacozoa,have body plans that lackbilateral symmetry.Their relationships are still disputed; the sister group to all other animals could be the Porifera or the Ctenophora,[117]both of which lackhox genes,which are important forbody plan development.[118]

Hox genes are found in the Placozoa,[119][120]Cnidaria,[121]and Bilateria.[122][123]6,331 groups ofgenescommon to all living animals have been identified; these may have arisen from a singlecommon ancestorthat lived650 million years agoin thePrecambrian.25 of these are novel core gene groups, found only in animals; of those, 8 are for essential components of theWntandTGF-betasignalling pathways which may have enabled animals to become multicellular by providing a pattern for the body's system of axes (in three dimensions), and another 7 are fortranscription factorsincludinghomeodomainproteins involved in thecontrol of development.[124][125]

Giribet and Edgecombe (2020) provide what they consider to be a consensus internal phylogeny of the animals, embodying uncertainty about the structure at the base of the tree (dashed lines).[126]

| Animalia | |

| multicellular |

An alternative phylogeny, from Kapli and colleagues (2021), proposes a cladeXenambulacrariafor the Xenacoelamorpha + Ambulacraria; this is either within Deuterostomia, as sister to Chordata, or the Deuterostomia are recovered as paraphyletic, and Xenambulacraria is sister to the proposed cladeCentroneuralia,consisting of Chordata + Protostomia.[127]

Non-bilateria

Several animal phyla lack bilateral symmetry. These are thePorifera(sea sponges),Placozoa,Cnidaria(which includesjellyfish,sea anemones,and corals), andCtenophora(comb jellies).

Sponges are physically very distinct from other animals, and were long thought to have diverged first, representing the oldest animal phylum and forming asister cladeto all other animals.[128]Despite their morphological dissimilarity with all other animals, genetic evidence suggests sponges may be more closely related to other animals than the comb jellies are.[129][130]Sponges lack the complex organization found in most other animal phyla;[131]their cells are differentiated, but in most cases not organised into distinct tissues, unlike all other animals.[132]They typically feed by drawing in water through pores, filtering out small particles of food.[133]

The comb jellies and Cnidaria are radially symmetric and have digestive chambers with a single opening, which serves as both mouth and anus.[134]Animals in both phyla have distinct tissues, but these are not organised into discreteorgans.[135]They arediploblastic,having only two main germ layers, ectoderm and endoderm.[136]

The tiny placozoans have no permanent digestive chamber and no symmetry; they superficially resemble amoebae.[137][138]Their phylogeny is poorly defined, and under active research.[129][139]

Bilateria

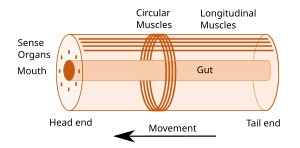

The remaining animals, the great majority—comprising some 29 phyla and over a million species—form aclade,the Bilateria, which have a bilaterally symmetricbody plan.The Bilateria aretriploblastic,with three well-developed germ layers, and their tissuesform distinct organs.The digestive chamber has two openings, a mouth and an anus, and there is an internal body cavity, acoelomor pseudocoelom. These animals have a head end (anterior) and a tail end (posterior), a back (dorsal) surface and a belly (ventral) surface, and a left and a right side.[140][141]

Having a front end means that this part of the body encounters stimuli, such as food, favouringcephalisation,the development of a head withsense organsand a mouth. Many bilaterians have a combination of circularmusclesthat constrict the body, making it longer, and an opposing set of longitudinal muscles, that shorten the body;[141]these enable soft-bodied animals with ahydrostatic skeletonto move byperistalsis.[142]They also have a gut that extends through the basically cylindrical body from mouth to anus. Many bilaterian phyla have primarylarvaewhich swim withciliaand have an apical organ containing sensory cells. However, over evolutionary time, descendant spaces have evolved which have lost one or more of each of these characteristics. For example, adult echinoderms are radially symmetric (unlike their larvae), while someparasitic wormshave extremely simplified body structures.[140][141]

Genetic studies have considerably changed zoologists' understanding of the relationships within the Bilateria. Most appear to belong to two major lineages, theprotostomesand thedeuterostomes.[143]It is often suggested that the basalmost bilaterians are theXenacoelomorpha,with all other bilaterians belonging to the subcladeNephrozoa[144][145][146]However, this suggestion has been contested, with other studies finding that xenacoelomorphs are more closely related to Ambulacraria than to other bilaterians.[127]

Protostomes and deuterostomes

Protostomes and deuterostomes differ in several ways. Early in development, deuterostome embryos undergo radialcleavageduring cell division, while many protostomes (theSpiralia) undergo spiral cleavage.[147] Animals from both groups possess a complete digestive tract, but in protostomes the first opening of theembryonic gutdevelops into the mouth, and the anus forms secondarily. In deuterostomes, the anus forms first while the mouth develops secondarily.[148][149]Most protostomes haveschizocoelous development,where cells simply fill in the interior of the gastrula to form the mesoderm. In deuterostomes, the mesoderm forms byenterocoelic pouching,through invagination of the endoderm.[150]

The main deuterostome phyla are the Echinodermata and the Chordata.[151]Echinoderms are exclusively marine and includestarfish,sea urchins,andsea cucumbers.[152]The chordates are dominated by thevertebrates(animals withbackbones),[153]which consist offishes,amphibians,reptiles,birds,andmammals.[154]The deuterostomes also include theHemichordata(acorn worms).[155][156]

Ecdysozoa

The Ecdysozoa are protostomes, named after their sharedtraitofecdysis,growth by moulting.[157]They include the largest animal phylum, theArthropoda,which contains insects, spiders, crabs, and their kin. All of these have a body divided intorepeating segments,typically with paired appendages. Two smaller phyla, theOnychophoraandTardigrada,are close relatives of the arthropods and share these traits. The ecdysozoans also include the Nematoda or roundworms, perhaps the second largest animal phylum. Roundworms are typically microscopic, and occur in nearly every environment where there is water;[158]some are important parasites.[159]Smaller phyla related to them are theNematomorphaor horsehair worms, and theKinorhyncha,Priapulida,andLoricifera.These groups have a reduced coelom, called a pseudocoelom.[160]

Spiralia

The Spiralia are a large group of protostomes that develop by spiral cleavage in the early embryo.[161]The Spiralia's phylogeny has been disputed, but it contains a large clade, the superphylumLophotrochozoa,and smaller groups of phyla such as theRouphozoawhich includes thegastrotrichsand theflatworms.All of these are grouped as thePlatytrochozoa,which has a sister group, theGnathifera,which includes therotifers.[162][163]

The Lophotrochozoa includes themolluscs,annelids,brachiopods,nemerteans,bryozoaandentoprocts.[162][164][165]The molluscs, the second-largest animal phylum by number of described species, includessnails,clams,andsquids,while the annelids are the segmented worms, such asearthworms,lugworms,andleeches.These two groups have long been considered close relatives because they sharetrochophorelarvae.[166][167]

History of classification

In theclassical era,Aristotledivided animals,[e]based on his own observations, into those with blood (roughly, the vertebrates) and those without. The animals were thenarranged on a scalefrom man (with blood, 2 legs, rational soul) down through the live-bearing tetrapods (with blood, 4 legs, sensitive soul) and other groups such as crustaceans (no blood, many legs, sensitive soul) down to spontaneously generating creatures like sponges (no blood, no legs, vegetable soul).Aristotlewas uncertain whether sponges were animals, which in his system ought to have sensation, appetite, and locomotion, or plants, which did not: he knew that sponges could sense touch, and would contract if about to be pulled off their rocks, but that they were rooted like plants and never moved about.[169]

In 1758,Carl Linnaeuscreated the firsthierarchicalclassification in hisSystema Naturae.[170]In his original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes ofVermes,Insecta,Pisces,Amphibia,Aves,andMammalia.Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, theChordata,while his Insecta (which included the crustaceans and arachnids) and Vermes have been renamed or broken up. The process was begun in 1793 byJean-Baptiste de Lamarck,who called the Vermesune espèce de chaos(a chaotic mess)[f]and split the group into three new phyla: worms, echinoderms, and polyps (which contained corals and jellyfish). By 1809, in hisPhilosophie Zoologique,Lamarck had created 9 phyla apart from vertebrates (where he still had 4 phyla: mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish) and molluscs, namelycirripedes,annelids, crustaceans, arachnids, insects, worms,radiates,polyps, andinfusorians.[168]

In his 1817Le Règne Animal,Georges Cuvierusedcomparative anatomyto group the animals into fourembranchements( "branches" with different body plans, roughly corresponding to phyla), namely vertebrates, molluscs, articulated animals (arthropods and annelids), andzoophytes (radiata)(echinoderms, cnidaria and other forms).[172]This division into four was followed by the embryologistKarl Ernst von Baerin 1828, the zoologistLouis Agassizin 1857, and the comparative anatomistRichard Owenin 1860.[173]

In 1874,Ernst Haeckeldivided the animal kingdom into two subkingdoms: Metazoa (multicellular animals, with five phyla: coelenterates, echinoderms, articulates, molluscs, and vertebrates) and Protozoa (single-celled animals), including a sixth animal phylum, sponges.[174][173]The protozoa were later moved to the former kingdomProtista,leaving only the Metazoa as a synonym of Animalia.[175]

In human culture

Practical uses

The human population exploits a large number of other animal species for food, both ofdomesticatedlivestock species inanimal husbandryand, mainly at sea, by hunting wild species.[176][177]Marine fish of many species arecaught commerciallyfor food. A smaller number of species arefarmed commercially.[176][178][179]Humans and theirlivestockmake up more than 90% of the biomass of all terrestrial vertebrates, and almost as much as all insects combined.[180]

Invertebratesincludingcephalopods,crustaceans,andbivalveorgastropodmolluscs are hunted or farmed for food.[181]Chickens,cattle,sheep,pigs,and other animals are raised as livestock for meat across the world.[177][182][183]Animal fibres such as wool are used to make textiles, while animalsinewshave been used as lashings and bindings, and leather is widely used to make shoes and other items. Animals have been hunted and farmed for their fur to make items such as coats and hats.[184]Dyestuffs includingcarmine(cochineal),[185][186]shellac,[187][188]andkermes[189][190]have been made from the bodies of insects.Working animalsincluding cattle and horses have been used for work and transport from the first days of agriculture.[191]

Animals such as the fruit flyDrosophila melanogasterserve a major role in science asexperimental models.[192][193][194][195]Animals have been used to createvaccinessince their discovery in the 18th century.[196]Some medicines such as the cancer drugtrabectedinare based ontoxinsor other molecules of animal origin.[197]

People have usedhunting dogsto help chase down and retrieve animals,[198]andbirds of preyto catch birds and mammals,[199]while tetheredcormorantshave beenused to catch fish.[200]Poison dart frogshave been used to poison the tips ofblowpipe darts.[201][202] A wide variety of animals are kept as pets, from invertebrates such as tarantulas, octopuses, andpraying mantises,[203]reptiles such assnakesandchameleons,[204]and birds includingcanaries,parakeets,andparrots[205]all finding a place. However, the most kept pet species are mammals, namelydogs,cats,andrabbits.[206][207][208]There is a tension between the role of animals as companions to humans, and their existence asindividuals with rightsof their own.[209]

A wide variety of terrestrial and aquatic animals are huntedfor sport.[210]

Symbolic uses

Thesigns of the WesternandChinese zodiacsare based on animals.[211][212]In China and Japan, thebutterflyhas been seen as thepersonificationof a person'ssoul,[213]and in classical representation the butterfly is also the symbol of the soul.[214][215]

Animals have been thesubjects of artfrom the earliest times, both historical, as in ancient Egypt, and prehistoric, as in thecave paintings at Lascaux.Major animal paintings includeAlbrecht Dürer's 1515The Rhinoceros,andGeorge Stubbs'sc. 1762horse portraitWhistlejacket.[216]Insects,birds and mammals play roles in literature and film,[217]such as ingiant bug movies.[218][219][220]

Animals includinginsects[213]and mammals[221]feature in mythology and religion. Thescarab beetlewas sacred inancient Egypt,[222]and thecow is sacred in Hinduism.[223]Among other mammals,deer,[221]horses,[224]lions,[225]bats,[226]bears,[227]andwolves[228]are the subjects of myths and worship.

See also

- Animal coloration

- Ethology

- Lists of organisms by population

- World Animal Day,observed on October 4

Notes

- ^Henneguya zschokkeidoes not have mitochondrial DNA or utilize aerobic respiration.[19]

- ^The application ofDNA barcodingto taxonomy further complicates this; a 2016 barcoding analysis estimated a total count of nearly 100,000insectspecies forCanadaalone, and extrapolated that the global insect fauna must be in excess of 10 million species, of which nearly 2 million are in a single fly family known as gall midges (Cecidomyiidae).[75]

- ^Not includingparasitoids.[71]

- ^CompareFile:Annelid redone w white background.svgfor a more specific and detailed model of a particular phylum with this general body plan.

- ^In hisHistory of AnimalsandParts of Animals.

- ^The French prefixune espèce deis pejorative.[171]

References

- ^de Queiroz, Kevin; Cantino, Philip; Gauthier, Jacques, eds. (2020). "Metazoa E. Haeckel 1874 [J. R. Garey and K. M. Halanych], converted clade name".Phylonyms: A Companion to the PhyloCode(1st ed.). CRC Press. p. 1352.doi:10.1201/9780429446276.ISBN9780429446276.S2CID242704712.

- ^Nielsen, Claus (2008). "Six major steps in animal evolution: are we derived sponge larvae?".Evolution & Development.10(2): 241–257.doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00231.x.PMID18315817.S2CID8531859.

- ^abcRothmaler, Werner (1951). "Die Abteilungen und Klassen der Pflanzen".Feddes Repertorium, Journal of Botanical Taxonomy and Geobotany.54(2–3): 256–266.doi:10.1002/fedr.19510540208.

- ^"animalia".Merriam-Webster Dictionary.Retrieved12 May2024.

- ^Antcliffe, Jonathan B.; Callow, Richard H. T.; Brasier, Martin D. (November 2014). "Giving the early fossil record of sponges a squeeze".Biological Reviews.89(4): 972–1004.doi:10.1111/brv.12090.PMID24779547.S2CID22630754.

- ^Cresswell, Julia (2010).The Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins(2nd ed.). New York:Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-954793-7.

'having the breath of life', from anima 'air, breath, life'.

- ^"Animal".The American Heritage Dictionary(4th ed.).Houghton Mifflin.2006.

- ^"animal".English Oxford Living Dictionaries.Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2018.Retrieved26 July2018.

- ^Boly, Melanie; Seth, Anil K.; Wilke, Melanie; Ingmundson, Paul; Baars, Bernard; Laureys, Steven; Edelman, David; Tsuchiya, Naotsugu (2013)."Consciousness in humans and non-human animals: recent advances and future directions".Frontiers in Psychology.4:625.doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00625.PMC3814086.PMID24198791.

- ^"The use of non-human animals in research".Royal Society.Archivedfrom the original on 12 June 2018.Retrieved7 June2018.

- ^"Nonhuman definition and meaning".Collins English Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 12 June 2018.Retrieved7 June2018.

- ^"Metazoan".Merriam-Webster.Archivedfrom the original on 6 July 2022.Retrieved6 July2022.

- ^"Metazoa".Collins.Archivedfrom the original on 30 July 2022.Retrieved6 July2022.and furthermeta- (sense 1)Archived30 July 2022 at theWayback Machineand-zoaArchived30 July 2022 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Avila, Vernon L. (1995).Biology: Investigating Life on Earth.Jones & Bartlett Learning.pp. 767–.ISBN978-0-86720-942-6.

- ^Davidson, Michael W."Animal Cell Structure".Archivedfrom the original on 20 September 2007.Retrieved20 September2007.

- ^"Palaeos:Metazoa".Palaeos.Archived fromthe originalon 28 February 2018.Retrieved25 February2018.

- ^Bergman, Jennifer."Heterotrophs".Archived fromthe originalon 29 August 2007.Retrieved30 September2007.

- ^Douglas, Angela E.; Raven, John A. (January 2003)."Genomes at the interface between bacteria and organelles".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.358(1429): 5–17.doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1188.PMC1693093.PMID12594915.

- ^Andrew, Scottie (26 February 2020)."Scientists discovered the first animal that doesn't need oxygen to live. It's changing the definition of what an animal can be".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2022.Retrieved28 February2020.

- ^Mentel, Marek; Martin, William (2010)."Anaerobic animals from an ancient, anoxic ecological niche".BMC Biology.8:32.doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-32.PMC2859860.PMID20370917.

- ^Saupe, S. G."Concepts of Biology".Archivedfrom the original on 21 November 2007.Retrieved30 September2007.

- ^Minkoff, Eli C. (2008).Barron's EZ-101 Study Keys Series: Biology(2nd, revised ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 48.ISBN978-0-7641-3920-8.

- ^Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002).Molecular Biology of the Cell(4th ed.).Garland Science.ISBN978-0-8153-3218-3.Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2016.Retrieved29 August2017.

- ^Sangwal, Keshra (2007).Additives and crystallization processes: from fundamentals to applications.John Wiley and Sons.p.212.ISBN978-0-470-06153-4.

- ^Becker, Wayne M. (1991).The world of the cell.Benjamin/Cummings.ISBN978-0-8053-0870-9.

- ^Magloire, Kim (2004).Cracking the AP Biology Exam, 2004–2005 Edition.The Princeton Review.p.45.ISBN978-0-375-76393-9.

- ^Starr, Cecie (2007).Biology: Concepts and Applications without Physiology.Cengage Learning. pp. 362, 365.ISBN978-0-495-38150-1.Retrieved19 May2020.

- ^Hillmer, Gero; Lehmann, Ulrich (1983).Fossil Invertebrates.Translated by J. Lettau. CUP Archive. p. 54.ISBN978-0-521-27028-1.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Knobil, Ernst (1998).Encyclopedia of reproduction, Volume 1.Academic Press. p.315.ISBN978-0-12-227020-8.

- ^Schwartz, Jill (2010).Master the GED 2011.Peterson's. p.371.ISBN978-0-7689-2885-3.

- ^Hamilton, Matthew B. (2009).Population genetics.Wiley-Blackwell.p.55.ISBN978-1-4051-3277-0.

- ^Ville, Claude Alvin; Walker, Warren Franklin; Barnes, Robert D. (1984).General zoology.Saunders College Pub. p. 467.ISBN978-0-03-062451-3.

- ^Hamilton, William James; Boyd, James Dixon; Mossman, Harland Winfield (1945).Human embryology: (prenatal development of form and function).Williams & Wilkins. p. 330.

- ^Philips, Joy B. (1975).Development of vertebrate anatomy.Mosby. p.176.ISBN978-0-8016-3927-2.

- ^The Encyclopedia Americana: a library of universal knowledge, Volume 10.Encyclopedia Americana Corp. 1918. p. 281.

- ^Romoser, William S.;Stoffolano, J. G. (1998).The science of entomology.WCB McGraw-Hill. p. 156.ISBN978-0-697-22848-2.

- ^Charlesworth, D.; Willis, J. H. (2009). "The genetics of inbreeding depression".Nature Reviews Genetics.10(11): 783–796.doi:10.1038/nrg2664.PMID19834483.S2CID771357.

- ^Bernstein, H.; Hopf, F. A.; Michod, R. E. (1987). "The Molecular Basis of the Evolution of Sex".Molecular Genetics of Development.Advances in Genetics. Vol. 24. pp. 323–370.doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60012-7.ISBN978-0-12-017624-3.PMID3324702.

- ^Pusey, Anne; Wolf, Marisa (1996). "Inbreeding avoidance in animals".Trends Ecol. Evol.11(5): 201–206.Bibcode:1996TEcoE..11..201P.doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10028-8.PMID21237809.

- ^Adiyodi, K. G.; Hughes, Roger N.; Adiyodi, Rita G. (July 2002).Reproductive Biology of Invertebrates, Volume 11, Progress in Asexual Reproduction.Wiley. p. 116.ISBN978-0-471-48968-9.

- ^Schatz, Phil."Concepts of Biology: How Animals Reproduce".OpenStax College.Archivedfrom the original on 6 March 2018.Retrieved5 March2018.

- ^Marchetti, Mauro; Rivas, Victoria (2001).Geomorphology and environmental impact assessment.Taylor & Francis. p. 84.ISBN978-90-5809-344-8.

- ^Levy, Charles K. (1973).Elements of Biology.Appleton-Century-Crofts.p. 108.ISBN978-0-390-55627-1.

- ^Begon, M.; Townsend, C.; Harper, J. (1996).Ecology: Individuals, populations and communities(Third ed.). Blackwell Science.ISBN978-0-86542-845-4.

- ^Allen, Larry Glen; Pondella, Daniel J.; Horn, Michael H. (2006).Ecology of marine fishes: California and adjacent waters.University of California Press.p. 428.ISBN978-0-520-24653-9.

- ^Caro, Tim(2005).Antipredator Defenses in Birds and Mammals.University of Chicago Press.pp. 1–6 and passim.

- ^Simpson, Alastair G.B; Roger, Andrew J. (2004)."The real 'kingdoms' of eukaryotes".Current Biology.14(17): R693–696.Bibcode:2004CBio...14.R693S.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.038.PMID15341755.S2CID207051421.

- ^Stevens, Alison N. P. (2010)."Predation, Herbivory, and Parasitism".Nature Education Knowledge.3(10): 36.Archivedfrom the original on 30 September 2017.Retrieved12 February2018.

- ^Jervis, M. A.; Kidd, N. A. C. (November 1986). "Host-Feeding Strategies in Hymenopteran Parasitoids".Biological Reviews.61(4): 395–434.doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1986.tb00660.x.S2CID84430254.

- ^Meylan, Anne (22 January 1988). "Spongivory in Hawksbill Turtles: A Diet of Glass".Science.239(4838): 393–395.Bibcode:1988Sci...239..393M.doi:10.1126/science.239.4838.393.JSTOR1700236.PMID17836872.S2CID22971831.

- ^Clutterbuck, Peter (2000).Understanding Science: Upper Primary.Blake Education. p. 9.ISBN978-1-86509-170-9.

- ^Gupta, P. K. (1900).Genetics Classical To Modern.Rastogi Publications. p. 26.ISBN978-81-7133-896-2.

- ^Garrett, Reginald; Grisham, Charles M. (2010).Biochemistry.Cengage Learning. p.535.ISBN978-0-495-10935-8.

- ^Castro, Peter; Huber, Michael E. (2007).Marine Biology(7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 376.ISBN978-0-07-722124-9.

- ^Rota-Stabelli, Omar; Daley, Allison C.; Pisani, Davide (2013)."Molecular Timetrees Reveal a Cambrian Colonization of Land and a New Scenario for Ecdysozoan Evolution".Current Biology.23(5): 392–8.Bibcode:2013CBio...23..392R.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.026.PMID23375891.

- ^Daeschler, Edward B.; Shubin, Neil H.; Jenkins, Farish A. Jr. (6 April 2006)."A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan".Nature.440(7085): 757–763.Bibcode:2006Natur.440..757D.doi:10.1038/nature04639.PMID16598249.

- ^Clack, Jennifer A.(21 November 2005). "Getting a Leg Up on Land".Scientific American.293(6): 100–7.Bibcode:2005SciAm.293f.100C.doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1205-100.PMID16323697.

- ^Margulis, Lynn;Schwartz, Karlene V.; Dolan, Michael (1999).Diversity of Life: The Illustrated Guide to the Five Kingdoms.Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 115–116.ISBN978-0-7637-0862-7.

- ^Clarke, Andrew (2014)."The thermal limits to life on Earth"(PDF).International Journal of Astrobiology.13(2): 141–154.Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..141C.doi:10.1017/S1473550413000438.Archived(PDF)from the original on 24 April 2019.

- ^"Land animals".British Antarctic Survey.Archivedfrom the original on 6 November 2018.Retrieved7 March2018.

- ^abcWood, Gerald (1983).The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats.Enfield, Middlesex: Guinness Superlatives.ISBN978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^Davies, Ella (20 April 2016)."The longest animal alive may be one you never thought of".BBC Earth.Archivedfrom the original on 19 March 2018.Retrieved1 March2018.

- ^"Largest mammal".Guinness World Records.Archivedfrom the original on 31 January 2018.Retrieved1 March2018.

- ^Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Christiansen, Per; Fariña, Richard A. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs".Historical Biology.16(2–4): 71–83.Bibcode:2004HBio...16...71M.CiteSeerX10.1.1.694.1650.doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132.S2CID56028251.

- ^Curtice, Brian (2020)."Society of Vertebrate Paleontology"(PDF).Vertpaleo.org.Archived(PDF)from the original on 19 October 2021.Retrieved30 December2022.

- ^Fiala, Ivan (10 July 2008)."Myxozoa".Tree of Life Web Project.Archivedfrom the original on 1 March 2018.Retrieved4 March2018.

- ^Kaur, H.; Singh, R. (2011)."Two new species of Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea: Bivalvulida) infecting an Indian major carp and a cat fish in wetlands of Punjab, India".Journal of Parasitic Diseases.35(2): 169–176.doi:10.1007/s12639-011-0061-4.PMC3235390.PMID23024499.

- ^abcdefghijklmnoZhang, Zhi-Qiang (30 August 2013)."Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity in 2013. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)".Zootaxa.3703(1): 5.doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.3.Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2019.Retrieved2 March2018.

- ^abcdefghijBalian, E. V.; Lévêque, C.; Segers, H.; Martens, K. (2008).Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment.Springer. p. 628.ISBN978-1-4020-8259-7.

- ^abcdefghijklmnHogenboom, Melissa."There are only 35 kinds of animal and most are really weird".BBC Earth.Archivedfrom the original on 10 August 2018.Retrieved2 March2018.

- ^abcdefghPoulin, Robert(2007).Evolutionary Ecology of Parasites.Princeton University Press.p.6.ISBN978-0-691-12085-0.

- ^abcdFelder, Darryl L.; Camp, David K. (2009).Gulf of Mexico Origin, Waters, and Biota: Biodiversity.Texas A&M University Press. p. 1111.ISBN978-1-60344-269-5.

- ^"How many species on Earth? About 8.7 million, new estimate says".24 August 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 1 July 2018.Retrieved2 March2018.

- ^Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina; Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Worm, Boris (23 August 2011). Mace, Georgina M. (ed.)."How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?".PLOS Biology.9(8): e1001127.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127.PMC3160336.PMID21886479.

- ^Hebert, Paul D.N.; Ratnasingham, Sujeevan; Zakharov, Evgeny V.; Telfer, Angela C.; Levesque-Beaudin, Valerie; Milton, Megan A.; Pedersen, Stephanie; Jannetta, Paul; deWaard, Jeremy R. (1 August 2016)."Counting animal species with DNA barcodes: Canadian insects".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.371(1702): 20150333.doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0333.PMC4971185.PMID27481785.

- ^Stork, Nigel E. (January 2018)."How Many Species of Insects and Other Terrestrial Arthropods Are There on Earth?".Annual Review of Entomology.63(1): 31–45.doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-020117-043348.PMID28938083.S2CID23755007.Stork notes that 1m insects have been named, making much larger predicted estimates.

- ^Poore, Hugh F. (2002)."Introduction".Crustacea: Malacostraca.Zoological catalogue of Australia. Vol. 19.2A.CSIRO Publishing.pp. 1–7.ISBN978-0-643-06901-5.

- ^abcdNicol, David (June 1969)."The Number of Living Species of Molluscs".Systematic Zoology.18(2): 251–254.doi:10.2307/2412618.JSTOR2412618.

- ^Uetz, P."A Quarter Century of Reptile and Amphibian Databases".Herpetological Review.52:246–255.Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2022.Retrieved2 October2021– via ResearchGate.

- ^abcReaka-Kudla, Marjorie L.; Wilson, Don E.;Wilson, Edward O.(1996).Biodiversity II: Understanding and Protecting Our Biological Resources.Joseph Henry Press. p. 90.ISBN978-0-309-52075-1.

- ^Burton, Derek; Burton, Margaret (2017).Essential Fish Biology: Diversity, Structure and Function.Oxford University Press. pp. 281–282.ISBN978-0-19-878555-2.

Trichomycteridae... includes obligate parasitic fish. Thus 17 genera from 2 subfamilies,Vandelliinae;4 genera, 9spp. andStegophilinae;13 genera, 31 spp. are parasites on gills (Vandelliinae) or skin (stegophilines) of fish.

- ^Sluys, R. (1999). "Global diversity of land planarians (Platyhelminthes, Tricladida, Terricola): a new indicator-taxon in biodiversity and conservation studies".Biodiversity and Conservation.8(12): 1663–1681.doi:10.1023/A:1008994925673.S2CID38784755.

- ^abPandian, T. J. (2020).Reproduction and Development in Platyhelminthes.CRC Press. pp. 13–14.ISBN978-1-000-05490-3.Retrieved19 May2020.

- ^Morand, Serge; Krasnov, Boris R.; Littlewood, D. Timothy J. (2015).Parasite Diversity and Diversification.Cambridge University Press. p. 44.ISBN978-1-107-03765-6.Retrieved2 March2018.

- ^Fontaneto, Diego."Marine Rotifers | An Unexplored World of Richness"(PDF).JMBA Global Marine Environment. pp. 4–5.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2 March 2018.Retrieved2 March2018.

- ^Chernyshev, A. V. (September 2021)."An updated classification of the phylum Nemertea".Invertebrate Zoology.18(3): 188–196.doi:10.15298/invertzool.18.3.01.S2CID239872311.Retrieved18 January2023.

- ^Hookabe, Natsumi; Kajihara, Hiroshi; Chernyshev, Alexei V.; Jimi, Naoto; Hasegawa, Naohiro; Kohtsuka, Hisanori; Okanishi, Masanori; Tani, Kenichiro; Fujiwara, Yoshihiro; Tsuchida, Shinji; Ueshima, Rei (2022)."Molecular Phylogeny of the Genus Nipponnemertes (Nemertea: Monostilifera: Cratenemertidae) and Descriptions of 10 New Species, With Notes on Small Body Size in a Newly Discovered Clade".Frontiers in Marine Science.9.doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.906383.Retrieved18 January2023.

- ^Hickman, Cleveland P.; Keen, Susan L.; Larson, Allan; Eisenhour, David J. (2018).Animal Diversity(8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.ISBN978-1-260-08427-6.

- ^Gold, David; et al. (22 February 2016)."Sterol and genomic analyses validate the sponge biomarker hypothesis".PNAS.113(10): 2684–2689.Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.2684G.doi:10.1073/pnas.1512614113.PMC4790988.PMID26903629.

- ^Love, Gordon; et al. (5 February 2009). "Fossil steroids record the appearance of Demospongiae during the Cryogenian period".Nature.457(7230): 718–721.Bibcode:2009Natur.457..718L.doi:10.1038/nature07673.PMID19194449.

- ^Shen, Bing; Dong, Lin; Xiao, Shuhai; Kowalewski, Michał (2008). "The Avalon Explosion: Evolution of Ediacara Morphospace".Science.319(5859): 81–84.Bibcode:2008Sci...319...81S.doi:10.1126/science.1150279.PMID18174439.S2CID206509488.

- ^Chen, Zhe; Chen, Xiang; Zhou, Chuanming; Yuan, Xunlai; Xiao, Shuhai (1 June 2018)."Late Ediacaran trackways produced by bilaterian animals with paired appendages".Science Advances.4(6): eaao6691.Bibcode:2018SciA....4.6691C.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao6691.PMC5990303.PMID29881773.

- ^Schopf, J. William (1999).Evolution!: facts and fallacies.Academic Press. p.7.ISBN978-0-12-628860-5.

- ^abBobrovskiy, Ilya; Hope, Janet M.; Ivantsov, Andrey; Nettersheim, Benjamin J.; Hallmann, Christian; Brocks, Jochen J. (20 September 2018)."Ancient steroids establish the Ediacaran fossil Dickinsonia as one of the earliest animals".Science.361(6408): 1246–1249.Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1246B.doi:10.1126/science.aat7228.PMID30237355.

- ^Zimorski, Verena; Mentel, Marek; Tielens, Aloysius G. M.; Martin, William F. (2019)."Energy metabolism in anaerobic eukaryotes and Earth's late oxygenation".Free Radical Biology and Medicine.140:279–294.doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.030.PMC6856725.PMID30935869.

- ^"Stratigraphic Chart 2022"(PDF).International Stratigraphic Commission. February 2022.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2 April 2022.Retrieved25 April2022.

- ^Maloof, A. C.; Porter, S. M.; Moore, J. L.; Dudas, F. O.; Bowring, S. A.; Higgins, J. A.; Fike, D. A.; Eddy, M. P. (2010). "The earliest Cambrian record of animals and ocean geochemical change".Geological Society of America Bulletin.122(11–12): 1731–1774.Bibcode:2010GSAB..122.1731M.doi:10.1130/B30346.1.S2CID6694681.

- ^"New Timeline for Appearances of Skeletal Animals in Fossil Record Developed by UCSB Researchers".The Regents of the University of California. 10 November 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 3 September 2014.Retrieved1 September2014.

- ^Conway-Morris, Simon(2003)."The Cambrian" explosion "of metazoans and molecular biology: would Darwin be satisfied?".The International Journal of Developmental Biology.47(7–8): 505–515.PMID14756326.Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2018.Retrieved28 February2018.

- ^"The Tree of Life".The Burgess Shale.Royal Ontario Museum.10 June 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 16 February 2018.Retrieved28 February2018.

- ^abDunn, F. S.; Kenchington, C. G.; Parry, L. A.; Clark, J. W.; Kendall, R. S.; Wilby, P. R. (25 July 2022)."A crown-group cnidarian from the Ediacaran of Charnwood Forest, UK".Nature Ecology & Evolution.6(8): 1095–1104.Bibcode:2022NatEE...6.1095D.doi:10.1038/s41559-022-01807-x.PMC9349040.PMID35879540.

- ^Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2005).Biology(7th ed.). Pearson, Benjamin Cummings. p. 526.ISBN978-0-8053-7171-0.

- ^Maloof, Adam C.; Rose, Catherine V.; Beach, Robert; Samuels, Bradley M.; Calmet, Claire C.; Erwin, Douglas H.; Poirier, Gerald R.; Yao, Nan; Simons, Frederik J. (17 August 2010). "Possible animal-body fossils in pre-Marinoan limestones from South Australia".Nature Geoscience.3(9): 653–659.Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..653M.doi:10.1038/ngeo934.

- ^Seilacher, Adolf;Bose, Pradip K.; Pfluger, Friedrich (2 October 1998). "Triploblastic animals more than 1 billion years ago: trace fossil evidence from india".Science.282(5386): 80–83.Bibcode:1998Sci...282...80S.doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.80.PMID9756480.

- ^Matz, Mikhail V.; Frank, Tamara M.; Marshall, N. Justin; Widder, Edith A.; Johnsen, Sönke (9 December 2008)."Giant Deep-Sea Protist Produces Bilaterian-like Traces".Current Biology.18(23): 1849–54.Bibcode:2008CBio...18.1849M.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.028.PMID19026540.S2CID8819675.

- ^Reilly, Michael (20 November 2008)."Single-celled giant upends early evolution".NBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 29 March 2013.Retrieved5 December2008.

- ^Bengtson, S. (2002)."Origins and early evolution of predation"(PDF).In Kowalewski, M.; Kelley, P. H. (eds.).The fossil record of predation.The Paleontological Society Papers.Vol. 8.The Paleontological Society.pp. 289–317.Archived(PDF)from the original on 30 October 2019.Retrieved3 March2018.

- ^Seilacher, Adolf(2007).Trace fossil analysis.Berlin: Springer. pp. 176–177.ISBN978-3-540-47226-1.OCLC191467085.

- ^Breyer, J. A. (1995). "Possible new evidence for the origin of metazoans prior to 1 Ga: Sediment-filled tubes from the Mesoproterozoic Allamoore Formation, Trans-Pecos Texas".Geology.23(3): 269–272.Bibcode:1995Geo....23..269B.doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0269:PNEFTO>2.3.CO;2.

- ^Budd, Graham E.; Jensen, Sören (2017)."The origin of the animals and a 'Savannah' hypothesis for early bilaterian evolution".Biological Reviews.92(1): 446–473.doi:10.1111/brv.12239.PMID26588818.

- ^Peterson, Kevin J.; Cotton, James A.; Gehling, James G.; Pisani, Davide (27 April 2008)."The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences.363(1496): 1435–1443.doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2233.PMC2614224.PMID18192191.

- ^Parfrey, Laura Wegener;Lahr, Daniel J. G.; Knoll, Andrew H.;Katz, Laura A.(16 August 2011)."Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.108(33): 13624–13629.Bibcode:2011PNAS..10813624P.doi:10.1073/pnas.1110633108.PMC3158185.PMID21810989.

- ^"Raising the Standard in Fossil Calibration".Fossil Calibration Database.Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2018.Retrieved3 March2018.

- ^Laumer, Christopher E.; Gruber-Vodicka, Harald; Hadfield, Michael G.; Pearse, Vicki B.; Riesgo, Ana; Marioni, John C.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2018)."Support for a clade of Placozoa and Cnidaria in genes with minimal compositional bias".eLife.2018, 7: e36278.doi:10.7554/eLife.36278.PMC6277202.PMID30373720.

- ^Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W. (2018)."Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes".Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology.66(1): 4–119.doi:10.1111/jeu.12691.PMC6492006.PMID30257078.

- ^Ros-Rocher, Núria; Pérez-Posada, Alberto; Leger, Michelle M.; Ruiz-Trillo, Iñaki (2021)."The origin of animals: an ancestral reconstruction of the unicellular-to-multicellular transition".Open Biology.11(2). The Royal Society: 200359.doi:10.1098/rsob.200359.ISSN2046-2441.PMC8061703.PMID33622103.

- ^Kapli, Paschalia; Telford, Maximilian J. (11 December 2020)."Topology-dependent asymmetry in systematic errors affects phylogenetic placement of Ctenophora and Xenacoelomorpha".Science Advances.6(10): eabc5162.Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5162K.doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc5162.PMC7732190.PMID33310849.

- ^Giribet, Gonzalo (27 September 2016)."Genomics and the animal tree of life: conflicts and future prospects".Zoologica Scripta.45:14–21.doi:10.1111/zsc.12215.

- ^"Evolution and Development"(PDF).Carnegie Institution for Science Department of Embryology.1 May 2012. p. 38. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2 March 2014.Retrieved4 March2018.

- ^Dellaporta, Stephen; Holland, Peter; Schierwater, Bernd; Jakob, Wolfgang; Sagasser, Sven; Kuhn, Kerstin (April 2004). "The Trox-2 Hox/ParaHox gene of Trichoplax (Placozoa) marks an epithelial boundary".Development Genes and Evolution.214(4): 170–175.doi:10.1007/s00427-004-0390-8.PMID14997392.S2CID41288638.

- ^Finnerty, John (June 2001). "Cnidarians Reveal Intermediate Stages in the Evolution of Hox Clusters and Axial Complexity".American Zoologist.41(3): 608–620.doi:10.1093/icb/41.3.608.

- ^Peterson, Kevin J.; Eernisse, Douglas J (2001). "Animal phylogeny and the ancestry of bilaterians: Inferences from morphology and 18S rDNA gene sequences".Evolution and Development.3(3): 170–205.CiteSeerX10.1.1.121.1228.doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003170.x.PMID11440251.S2CID7829548.

- ^Kraemer-Eis, Andrea; Ferretti, Luca; Schiffer, Philipp; Heger, Peter; Wiehe, Thomas (2016)."A catalogue of Bilaterian-specific genes – their function and expression profiles in early development"(PDF).bioRxiv.doi:10.1101/041806.S2CID89080338.Archived(PDF)from the original on 26 February 2018.

- ^Zimmer, Carl(4 May 2018)."The Very First Animal Appeared Amid an Explosion of DNA".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 4 May 2018.Retrieved4 May2018.

- ^Paps, Jordi; Holland, Peter W. H. (30 April 2018)."Reconstruction of the ancestral metazoan genome reveals an increase in genomic novelty".Nature Communications.9(1730 (2018)): 1730.Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.1730P.doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04136-5.PMC5928047.PMID29712911.

- ^Giribet, G.; Edgecombe, G.D. (2020).The Invertebrate Tree of Life.Princeton University Press.p. 21.ISBN978-0-6911-7025-1.Retrieved27 May2023.

- ^abKapli, Paschalia; Natsidis, Paschalis; Leite, Daniel J.; Fursman, Maximilian; Jeffrie, Nadia; Rahman, Imran A.; Philippe, Hervé; Copley, Richard R.; Telford, Maximilian J. (19 March 2021)."Lack of support for Deuterostomia prompts reinterpretation of the first Bilateria".Science Advances.7(12): eabe2741.Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2741K.doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe2741.ISSN2375-2548.PMC7978419.PMID33741592.

- ^Bhamrah, H. S.; Juneja, Kavita (2003).An Introduction to Porifera.Anmol Publications. p. 58.ISBN978-81-261-0675-2.

- ^abSchultz, Darrin T.; Haddock, Steven H. D.; Bredeson, Jessen V.; Green, Richard E.; Simakov, Oleg; Rokhsar, Daniel S. (17 May 2023)."Ancient gene linkages support ctenophores as sister to other animals".Nature.618(7963): 110–117.Bibcode:2023Natur.618..110S.doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05936-6.ISSN0028-0836.PMC10232365.PMID37198475.S2CID258765122.

- ^Whelan, Nathan V.; Kocot, Kevin M.; Moroz, Tatiana P.; Mukherjee, Krishanu; Williams, Peter; Paulay, Gustav; Moroz, Leonid L.; Halanych, Kenneth M. (9 October 2017)."Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals".Nature Ecology & Evolution.1(11): 1737–1746.Bibcode:2017NatEE...1.1737W.doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0331-3.ISSN2397-334X.PMC5664179.PMID28993654.

- ^Sumich, James L. (2008).Laboratory and Field Investigations in Marine Life.Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 67.ISBN978-0-7637-5730-4.

- ^Jessop, Nancy Meyer (1970).Biosphere; a study of life.Prentice-Hall.p. 428.

- ^Sharma, N. S. (2005).Continuity And Evolution Of Animals.Mittal Publications. p. 106.ISBN978-81-8293-018-6.

- ^Langstroth, Lovell; Langstroth, Libby (2000). Newberry, Todd (ed.).A Living Bay: The Underwater World of Monterey Bay.University of California Press. p.244.ISBN978-0-520-22149-9.

- ^Safra, Jacob E. (2003).The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 16.Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 523.ISBN978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^Kotpal, R.L. (2012).Modern Text Book of Zoology: Invertebrates.Rastogi Publications. p. 184.ISBN978-81-7133-903-7.

- ^Barnes, Robert D. (1982).Invertebrate Zoology.Holt-Saunders International. pp. 84–85.ISBN978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^"Introduction to Placozoa".UCMP Berkeley.Archivedfrom the original on 25 March 2018.Retrieved10 March2018.

- ^Srivastava, Mansi; Begovic, Emina; Chapman, Jarrod; Putnam, Nicholas H.; Hellsten, Uffe; Kawashima, Takeshi; Kuo, Alan; Mitros, Therese; Salamov, Asaf; Carpenter, Meredith L.; Signorovitch, Ana Y.; Moreno, Maria A.; Kamm, Kai; Grimwood, Jane; Schmutz, Jeremy (1 August 2008)."The Trichoplax genome and the nature of placozoans".Nature.454(7207): 955–960.Bibcode:2008Natur.454..955S.doi:10.1038/nature07191.ISSN0028-0836.PMID18719581.S2CID4415492.

- ^abMinelli, Alessandro (2009).Perspectives in Animal Phylogeny and Evolution.Oxford University Press.p. 53.ISBN978-0-19-856620-5.

- ^abcBrusca, Richard C. (2016). "Introduction to the Bilateria and the Phylum Xenacoelomorpha | Triploblasty and Bilateral Symmetry Provide New Avenues for Animal Radiation".Invertebrates(PDF).Sinauer Associates.pp. 345–372.ISBN978-1-60535-375-3.Archived(PDF)from the original on 24 April 2019.Retrieved4 March2018.

- ^Quillin, K. J. (May 1998)."Ontogenetic scaling of hydrostatic skeletons: geometric, static stress and dynamic stress scaling of the earthworm lumbricus terrestris".Journal of Experimental Biology.201(12): 1871–1883.doi:10.1242/jeb.201.12.1871.PMID9600869.Archivedfrom the original on 17 June 2020.Retrieved4 March2018.

- ^Telford, Maximilian J. (2008)."Resolving Animal Phylogeny: A Sledgehammer for a Tough Nut?".Developmental Cell.14(4): 457–459.doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.016.PMID18410719.

- ^Philippe, H.; Brinkmann, H.; Copley, R.R.; Moroz, L. L.; Nakano, H.; Poustka, A.J.; Wallberg, A.; Peterson, K. J.; Telford, M.J. (2011)."Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related toXenoturbella".Nature.470(7333): 255–258.Bibcode:2011Natur.470..255P.doi:10.1038/nature09676.PMC4025995.PMID21307940.

- ^Perseke, M.; Hankeln, T.; Weich, B.; Fritzsch, G.; Stadler, P.F.; Israelsson, O.; Bernhard, D.; Schlegel, M. (August 2007)."The mitochondrial DNA of Xenoturbella bocki: genomic architecture and phylogenetic analysis"(PDF).Theory Biosci.126(1): 35–42.CiteSeerX10.1.1.177.8060.doi:10.1007/s12064-007-0007-7.PMID18087755.S2CID17065867.Archived(PDF)from the original on 24 April 2019.Retrieved4 March2018.

- ^Cannon, Johanna T.; Vellutini, Bruno C.; Smith III, Julian.; Ronquist, Frederik; Jondelius, Ulf; Hejnol, Andreas (3 February 2016)."Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa".Nature.530(7588): 89–93.Bibcode:2016Natur.530...89C.doi:10.1038/nature16520.PMID26842059.S2CID205247296.Archivedfrom the original on 30 July 2022.Retrieved21 February2022.

- ^Valentine, James W. (July 1997)."Cleavage patterns and the topology of the metazoan tree of life".PNAS.94(15): 8001–8005.Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.8001V.doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8001.PMC21545.PMID9223303.

- ^Peters, Kenneth E.; Walters, Clifford C.; Moldowan, J. Michael (2005).The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and isotopes in petroleum systems and Earth history.Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 717.ISBN978-0-521-83762-0.

- ^Hejnol, A.; Martindale, M.Q. (2009). "The mouth, the anus, and the blastopore – open questions about questionable openings". In Telford, M.J.; Littlewood, D.J. (eds.).Animal Evolution – Genomes, Fossils, and Trees.Oxford University Press. pp. 33–40.ISBN978-0-19-957030-0.Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2018.Retrieved1 March2018.

- ^Safra, Jacob E. (2003).The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1; Volume 3.Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 767.ISBN978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^Hyde, Kenneth (2004).Zoology: An Inside View of Animals.Kendall Hunt.p. 345.ISBN978-0-7575-0997-1.

- ^Alcamo, Edward (1998).Biology Coloring Workbook.The Princeton Review.p. 220.ISBN978-0-679-77884-4.

- ^Holmes, Thom (2008).The First Vertebrates.Infobase Publishing. p. 64.ISBN978-0-8160-5958-4.

- ^Rice, Stanley A. (2007).Encyclopedia of evolution.Infobase Publishing. p.75.ISBN978-0-8160-5515-9.

- ^Tobin, Allan J.; Dusheck, Jennie (2005).Asking about life.Cengage Learning. p. 497.ISBN978-0-534-40653-0.

- ^Simakov, Oleg; Kawashima, Takeshi; Marlétaz, Ferdinand; Jenkins, Jerry; Koyanagi, Ryo; Mitros, Therese; Hisata, Kanako; Bredeson, Jessen; Shoguchi, Eiichi (26 November 2015)."Hemichordate genomes and deuterostome origins".Nature.527(7579): 459–465.Bibcode:2015Natur.527..459S.doi:10.1038/nature16150.PMC4729200.PMID26580012.

- ^Dawkins, Richard(2005).The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution.Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.p.381.ISBN978-0-618-61916-0.

- ^Prewitt, Nancy L.; Underwood, Larry S.; Surver, William (2003).BioInquiry: making connections in biology.John Wiley. p.289.ISBN978-0-471-20228-8.

- ^Schmid-Hempel, Paul (1998).Parasites in social insects.Princeton University Press.p. 75.ISBN978-0-691-05924-2.

- ^Miller, Stephen A.; Harley, John P. (2006).Zoology.McGraw-Hill.p. 173.ISBN978-0-07-063682-8.

- ^Shankland, M.; Seaver, E.C. (2000)."Evolution of the bilaterian body plan: What have we learned from annelids?".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.97(9): 4434–4437.Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.4434S.doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4434.JSTOR122407.PMC34316.PMID10781038.

- ^abStruck, Torsten H.; Wey-Fabrizius, Alexandra R.; Golombek, Anja; Hering, Lars; Weigert, Anne; Bleidorn, Christoph; Klebow, Sabrina; Iakovenko, Nataliia; Hausdorf, Bernhard; Petersen, Malte; Kück, Patrick; Herlyn, Holger; Hankeln, Thomas (2014)."Platyzoan Paraphyly Based on Phylogenomic Data Supports a Noncoelomate Ancestry of Spiralia".Molecular Biology and Evolution.31(7): 1833–1849.doi:10.1093/molbev/msu143.PMID24748651.

- ^Fröbius, Andreas C.; Funch, Peter (April 2017)."Rotiferan Hox genes give new insights into the evolution of metazoan bodyplans".Nature Communications.8(1): 9.Bibcode:2017NatCo...8....9F.doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00020-w.PMC5431905.PMID28377584.

- ^Hervé, Philippe; Lartillot, Nicolas; Brinkmann, Henner (May 2005)."Multigene Analyses of Bilaterian Animals Corroborate the Monophyly of Ecdysozoa, Lophotrochozoa, and Protostomia".Molecular Biology and Evolution.22(5): 1246–1253.doi:10.1093/molbev/msi111.PMID15703236.

- ^Speer, Brian R. (2000)."Introduction to the Lophotrochozoa | Of molluscs, worms, and lophophores..."UCMP Berkeley. Archived fromthe originalon 16 August 2000.Retrieved28 February2018.

- ^Giribet, G.; Distel, D.L.; Polz, M.; Sterrer, W.; Wheeler, W.C. (2000)."Triploblastic relationships with emphasis on the acoelomates and the position of Gnathostomulida, Cycliophora, Plathelminthes, and Chaetognatha: a combined approach of 18S rDNA sequences and morphology".Syst Biol.49(3): 539–562.doi:10.1080/10635159950127385.PMID12116426.

- ^Kim, Chang Bae; Moon, Seung Yeo; Gelder, Stuart R.; Kim, Won (September 1996). "Phylogenetic Relationships of Annelids, Molluscs, and Arthropods Evidenced from Molecules and Morphology".Journal of Molecular Evolution.43(3): 207–215.Bibcode:1996JMolE..43..207K.doi:10.1007/PL00006079.PMID8703086.

- ^abGould, Stephen Jay(2011).The Lying Stones of Marrakech.Harvard University Press. pp. 130–134.ISBN978-0-674-06167-5.

- ^Leroi, Armand Marie(2014).The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science.Bloomsbury. pp. 111–119, 270–271.ISBN978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^Linnaeus, Carl(1758).Systema naturae per regna tria naturae:secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis(in Latin) (10thed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii).Archivedfrom the original on 10 October 2008.Retrieved22 September2008.

- ^"Espèce de".Reverso Dictionnnaire.Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2013.Retrieved1 March2018.

- ^De Wit, Hendrik C. D. (1994).Histoire du Développement de la Biologie, Volume III.Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes. pp. 94–96.ISBN978-2-88074-264-5.

- ^abValentine, James W. (2004).On the Origin of Phyla.University of Chicago Press. pp. 7–8.ISBN978-0-226-84548-7.

- ^Haeckel, Ernst(1874).Anthropogenie oder Entwickelungsgeschichte des menschen(in German). W. Engelmann. p. 202.

- ^Hutchins, Michael (2003).Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia(2nd ed.). Gale. p.3.ISBN978-0-7876-5777-2.

- ^ab"Fisheries and Aquaculture".Food and Agriculture Organization.Archivedfrom the original on 19 May 2009.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^ab"Graphic detail Charts, maps and infographics. Counting chickens".The Economist.27 July 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 15 July 2016.Retrieved23 June2016.

- ^Helfman, Gene S. (2007).Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources.Island Press. p.11.ISBN978-1-59726-760-1.

- ^"World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture"(PDF).FAO.Archived(PDF)from the original on 28 August 2015.Retrieved13 August2015.

- ^Eggleton, Paul (17 October 2020)."The State of the World's Insects".Annual Review of Environment and Resources.45(1): 61–82.doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-050035.ISSN1543-5938.

- ^"Shellfish climbs up the popularity ladder".Seafood Business.January 2002. Archived fromthe originalon 5 November 2012.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^"Breeds of Cattle at Cattle Today".Cattle-today.Archivedfrom the original on 15 July 2011.Retrieved15 October2013.

- ^Lukefahr, S. D.; Cheeke, P. R."Rabbit project development strategies in subsistence farming systems".Food and Agriculture Organization.Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2016.Retrieved23 June2016.

- ^"Ancient fabrics, high-tech geotextiles".Natural Fibres. Archived fromthe originalon 20 July 2016.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^"Cochineal and Carmine".Major colourants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems.FAO.Archivedfrom the original on 6 March 2018.Retrieved16 June2015.

- ^"Guidance for Industry: Cochineal Extract and Carmine".FDA.Archivedfrom the original on 13 July 2016.Retrieved6 July2016.

- ^"How Shellac Is Manufactured".The Mail (Adelaide, SA: 1912–1954).18 December 1937.Archivedfrom the original on 30 July 2022.Retrieved17 July2015.

- ^Pearnchob, N.; Siepmann, J.; Bodmeier, R. (2003). "Pharmaceutical applications of shellac: moisture-protective and taste-masking coatings and extended-release matrix tablets".Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy.29(8): 925–938.doi:10.1081/ddc-120024188.PMID14570313.S2CID13150932.

- ^Barber, E. J. W. (1991).Prehistoric Textiles.Princeton University Press. pp. 230–231.ISBN978-0-691-00224-8.

- ^Munro, John H. (2003). "Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Technology, and Organisation". In Jenkins, David (ed.).The Cambridge History of Western Textiles.Cambridge University Press. pp. 214–215.ISBN978-0-521-34107-3.

- ^Pond, Wilson G. (2004).Encyclopedia of Animal Science.CRC Press. pp. 248–250.ISBN978-0-8247-5496-9.Retrieved22 February2018.

- ^"Genetics Research".Animal Health Trust. Archived fromthe originalon 12 December 2017.Retrieved24 June2016.

- ^"Drug Development".Animal Research.info.Archivedfrom the original on 8 June 2016.Retrieved24 June2016.

- ^"Animal Experimentation".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 1 July 2016.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^"EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers".Speaking of Research. 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 6 October 2017.Retrieved24 January2016.

- ^"Vaccines and animal cell technology".Animal Cell Technology Industrial Platform. 10 June 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 13 July 2016.Retrieved9 July2016.

- ^"Medicines by Design".National Institute of Health.Archivedfrom the original on 4 June 2016.Retrieved9 July2016.

- ^Fergus, Charles (2002).Gun Dog Breeds, A Guide to Spaniels, Retrievers, and Pointing Dogs.The Lyons Press.ISBN978-1-58574-618-7.

- ^"History of Falconry".The Falconry Centre.Archivedfrom the original on 29 May 2016.Retrieved22 April2016.

- ^King, Richard J. (2013).The Devil's Cormorant: A Natural History.University of New Hampshire Press. p. 9.ISBN978-1-61168-225-0.

- ^"AmphibiaWeb – Dendrobatidae".AmphibiaWeb.Archivedfrom the original on 10 August 2011.Retrieved10 October2008.

- ^Heying, H. (2003)."Dendrobatidae".Animal Diversity Web.Archivedfrom the original on 12 February 2011.Retrieved9 July2016.

- ^"Other bugs".Keeping Insects. 18 February 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2016.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^Kaplan, Melissa."So, you think you want a reptile?".Anapsid.org.Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2016.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^"Pet Birds".PDSA.Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2016.Retrieved8 July2016.

- ^"Animals in Healthcare Facilities"(PDF).2012. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 March 2016.

- ^The Humane Society of the United States."U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics".Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2012.Retrieved27 April2012.

- ^"U.S. Rabbit Industry profile"(PDF).United States Department of Agriculture.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 20 October 2013.Retrieved10 July2013.

- ^Plous, S. (1993). "The Role of Animals in Human Society".Journal of Social Issues.49(1): 1–9.doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00906.x.

- ^Hummel, Richard (1994).Hunting and Fishing for Sport: Commerce, Controversy, Popular Culture.Popular Press.ISBN978-0-87972-646-1.

- ^Lau, Theodora (2005).The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes.Souvenir Press. pp. 2–8, 30–35, 60–64, 88–94, 118–124, 148–153, 178–184, 208–213, 238–244, 270–278, 306–312, 338–344.

- ^Tester, S. Jim (1987).A History of Western Astrology.Boydell & Brewer. pp. 31–33 and passim.ISBN978-0-85115-446-6.

- ^abHearn, Lafcadio(1904).Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.Dover.ISBN978-0-486-21901-1.

- ^De Jaucourt, Louis (January 2011)."Butterfly".Encyclopedia of Diderot and d'Alembert.Archivedfrom the original on 11 August 2016.Retrieved16 December2023.

- ^Hutchins, M., Arthur V. Evans, Rosser W. Garrison and Neil Schlager (Eds) (2003),Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia,2nd edition. Volume 3, Insects. Gale, 2003.

- ^Jones, Jonathan (27 June 2014)."The top 10 animal portraits in art".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2016.Retrieved24 June2016.

- ^Paterson, Jennifer (29 October 2013)."Animals in Film and Media".Oxford Bibliographies.doi:10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0044.Archivedfrom the original on 14 June 2016.Retrieved24 June2016.

- ^Gregersdotter, Katarina; Höglund, Johan; Hållén, Nicklas (2016).Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism.Springer. p. 147.ISBN978-1-137-49639-3.

- ^Warren, Bill; Thomas, Bill (2009).Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition.McFarland & Company.p. 32.ISBN978-1-4766-2505-8.

- ^Crouse, Richard (2008).Son of the 100 Best Movies You've Never Seen.ECW Press. p. 200.ISBN978-1-55490-330-6.

- ^ab"Deer".Trees for Life.Archivedfrom the original on 14 June 2016.Retrieved23 June2016.

- ^Ben-Tor, Daphna (1989).Scarabs, A Reflection of Ancient Egypt.Jerusalem: Israel Museum. p. 8.ISBN978-965-278-083-6.

- ^Biswas, Soutik (15 October 2015)."Why the humble cow is India's most polarising animal".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 22 November 2016.Retrieved9 July2016.

- ^van Gulik, Robert Hans.Hayagrīva: The Mantrayānic Aspect of Horse-cult in China and Japan.Brill Archive. p. 9.

- ^Grainger, Richard (24 June 2012)."Lion Depiction across Ancient and Modern Religions".Alert. Archived fromthe originalon 23 September 2016.Retrieved6 July2016.

- ^Read, Kay Almere; Gonzalez, Jason J. (2000).Mesoamerican Mythology.Oxford University Press.pp. 132–134.

- ^Wunn, Ina (January 2000). "Beginning of Religion".Numen.47(4): 417–452.doi:10.1163/156852700511612.S2CID53595088.

- ^McCone, Kim R. (1987). "Hund, Wolf, und Krieger bei den Indogermanen". In Meid, W. (ed.).Studien zum indogermanischen Wortschatz.Innsbruck. pp. 101–154.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

Media related toAnimalsat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toAnimalsat Wikimedia Commons Data related toAnimalat Wikispecies

Data related toAnimalat Wikispecies- Tree of Life Project.Archived12 June 2011 at theWayback Machine

- Animal Diversity Web–University of Michigan's database of animals

- Wildscreen Arkive– multimedia database of endangered/protected species

![Dickinsonia costata from the Ediacaran biota (c. 635–542 mya) is one of the earliest animal species known.[94]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/DickinsoniaCostata.jpg/320px-DickinsoniaCostata.jpg)

![Auroralumina attenboroughii, an Ediacaran predator (c. 560 mya)[101]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/Auroralumina_attenboroughii_reconstruction.jpg/209px-Auroralumina_attenboroughii_reconstruction.jpg)