Medievalism

Medievalismis a system of belief and practice inspired by theMiddle Agesof Europe, or by devotion to elements of that period, which have been expressed in areas such as architecture, literature, music, art, philosophy, scholarship, and various vehicles ofpopular culture.[1][2]Since the 17th century, a variety of movements have used the medieval period as a model or inspiration for creative activity, includingRomanticism,theGothic revival,thepre-Raphaeliteandarts and crafts movements,andneo-medievalism(a term often used interchangeably withmedievalism). Historians have attempted to conceptualize the history of non-European countries in terms of medievalisms, but the approach has been controversial among scholars of Latin America, Africa, and Asia.[3]

Renaissance to Enlightenment[edit]

In the 1330s,Petrarchexpressed the viewthat European culture had stagnated and drifted into what he called the"Dark Ages",since thefall of Romein the fifth century, owing to among other things, the loss of many classical Latin texts and to the corruption of the language in contemporary discourse.[4]Scholars of theRenaissancebelieved that they lived in a new age that broke free of the decline described by Petrarch. HistoriansLeonardo BruniandFlavio Biondodeveloped athree tieroutline of history composed ofAncient,Medieval, andModern.[5]The Latin termmedia tempestas(middle time) first appears in 1469.[6]The termmedium aevum(Middle Ages) is first recorded in 1604.[6]"Medieval" first appears in the nineteenth century and is an Anglicised form ofmedium aevum.[7]

During theReformationsof the 16th and 17th centuries, Protestants generally followed the critical views expressed by Renaissance Humanists, but for additional reasons. They saw classical antiquity as a golden time, not only because of Latin literature, but because it was the early beginnings of Christianity. The intervening 1000 year Middle Age was a time of darkness, not only because of lack of secular Latin literature, but because of corruption within the Church such as Popes who ruled as kings, pagan superstitions withsaints' relics,celibate priesthood, and institutionalized moral hypocrisy.[8]Most Protestant historians did not date the beginnings of the modern era from the Renaissance, but later, from the beginnings of the Reformation.[9]

In theAge of Enlightenmentof the 17th and 18th centuries, the Middle Ages was seen as an "Age of Faith" when religion reigned, and thus as a period contrary to reason and contrary to the spirit of the Enlightenment.[10]For them the Middle Ages was barbaric and priest-ridden. They referred to "these dark times", "the centuries of ignorance", and "the uncouth centuries".[11]The Protestant critique of the Medieval Church was taken into Enlightenment thinking by works includingEdward Gibbon'sDecline and Fall of the Roman Empire(1776–89).[12]Voltairewas particularly energetic in attacking the religiously dominated Middle Ages as a period of social stagnation and decline, condemningFeudalism,Scholasticism,The Crusades,The Inquisitionand theCatholic Churchin general.[11]

Gothic revival[edit]

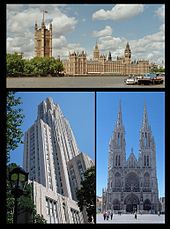

The Gothic Revival was anarchitectural movementwhich began in the 1740s inEngland.[13]Its popularity grew rapidly in the early nineteenth century, when increasingly serious and learned admirers of neo-Gothic styles sought to revive medieval forms in contrast to theclassicalstyles prevalent at the time.[14]In England, the epicentre of this revival, it was intertwined with deeply philosophical movements associated with a re-awakening of "High Church" orAnglo-Catholicself-belief (and by the Catholic convertAugustus Welby Pugin) concerned by the growth of religious nonconformism.[13]He went on to produce important Gothic buildings such as Cathedrals atBirminghamandSouthwarkand theBritish Houses of Parliamentin the 1840s.[15]Large numbers of existing English churches had features such ascrosses,screensandstained glass(removedat the Reformation), restored or added, and most new Anglican and Catholic churches were built in the Gothic style.[16]Viollet-le-Ducwas a leading figure in the movement in France, restoring the entire walled city ofCarcassonneas well asNotre-DameandSainte Chapellein Paris.[15]In AmericaRalph Adams Cramwas a leading force in American Gothic, with his most ambitious project theCathedral of St. John the Divinein New York (one of the largest cathedrals in the world), as well asCollegiate Gothicbuildings atPrinceton Graduate College.[15]On a wider level the woodenCarpenter Gothicchurches and houses were built in large numbers across North America in this period.[17]

In English literature, the architectural Gothic Revival and classical Romanticism gave rise to theGothic novel,often dealing with dark themes in human nature against medieval backdrops and with elements of the supernatural.[18]Beginning withThe Castle of Otranto(1764) byHorace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford,it also includedMary Shelley'sFrankenstein(1818) andJohn Polidori'sThe Vampyre(1819), which helped found the modern horror genre.[19]This helped create thedark romanticism or American Gothicof authors likeEdgar Allan Poein works including "The Fall of the House of Usher"(1839) and"The Pit and the Pendulum"(1842) andNathanial Hawthornein "The Minister's Black Veil"(1836) and"The Birth-Mark"(1843).[20]This in turn influenced American novelists likeHerman Melvillein works such asMoby-Dick(1851).[21]Early Victorian Gothic novels includedEmily Brontë'sWuthering Heights(1847) andCharlotte Brontë'sJane Eyre(1847).[22]The genre was revived and modernised toward the end of the century with works likeRobert Louis Stevenson'sStrange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde(1886),Oscar Wilde'sThe Picture of Dorian Gray(1890) andBram Stoker'sDracula(1897).[23]

Anglo-Saxonism[edit]

Main article:Anglo-Saxonism in the 19th century

The development of philology through the 17th-19th centuries as a subject of study in north west Europe and England saw increased interest in tracing the so-called 'roots' of languages and cultures including English, German, Icelandic and Dutch. Antiquaries of the time believed that languages and cultures were intertwined, andOld Englishtexts, especiallyBeowulf,were claimed by antiquarians from each linguistic-cultural group as 'their' oldest poem.[24]

In England, Rebecca Brackmann argues that an increased interest in Old English and imagined Anglo-Saxon culture was a result of, and in turn fuelled, political upheaval in the 17th and 18th centuries.[25] Great Seal of the United States In the United States, Anglo-Saxon mythologies persisted, withThomas Jeffersonproposing thatHengist and Horsawere shown on theGreat Seal of the United States.[26]

Romanticism[edit]

Romanticism was a complex artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the eighteenth century inWestern Europe,and gained strength during and after theIndustrialandFrench Revolutions.[27]It was partly a revolt against the political norms of the Age of Enlightenment which rationalised nature, and was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature.[27]Romanticism has been seen as "the revival of the life and thought of the Middle Ages",[28]reaching beyondrationalandClassicistmodels to elevate medievalism and elements of art and narrative perceived to be authentically medieval, in an attempt to escape the confines of population growth, urban sprawl and industrialism, embracing the exotic, unfamiliar and distant.[28][29]

The name "Romanticism" itself was derived from the medieval genrechivalric romance.This movement contributed to the strong influence of such romances, disproportionate to their actual showing among medieval literature, on the image of Middle Ages, such that a knight, a distressed damsel, and a dragon is used to conjure up the time pictorially.[30]The Romantic interest in the medieval can particularly be seen in the illustrations of English poetWilliam Blakeand theOssiancycle published by Scottish poetJames Macphersonin 1762, which inspired bothGoethe'sGötz von Berlichingen(1773), and the youngWalter Scott.The latter'sWaverley Novels,includingIvanhoe(1819) andQuentin Durward(1823) helped popularise, and shape views of, the medieval era.[31]The same impulse manifested itself in the translation of medievalnational epicsinto modern vernacular languages, includingNibelungenlied(1782) in Germany,[32]The Lay of the Cid(1799) in Spain,[33]Beowulf(1833) in England,[34]The Song of Roland(1837) in France,[35]which were widely read and highly influential on subsequent literary and artistic work.[36]

The Nazarenes[edit]

The nameNazarenewas adopted by a group of early nineteenth-centuryGermanRomanticpainterswho reacted againstNeoclassicismand hoped to return to art which embodied spiritual values. They sought inspiration in artists of theLate Middle Agesand theearly Renaissance,rejecting what they saw as the superficial virtuosity of later art.[37]The name Nazarene came from a term of derision used against them for their affectation of a biblical manner of clothing and hair style.[37]The movement was originally formed in 1809 by six students at theVienna Academyand called the Brotherhood of St. Luke orLukasbund,after thepatron saintof medieval artists.[38]In 1810 four of them,Johann Friedrich Overbeck,Franz Pforr,Ludwig Vogeland Johann Konrad Hottinger moved toRome,where they occupied the abandoned monastery of San Isidoro and were joined byPhilipp Veit,Peter von Cornelius,Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld,Friedrich Wilhelm Schadowand a loose grouping of other German artists.[37]They met up with Austrian romantic landscape artistJoseph Anton Koch(1768–1839) who became an unofficial tutor to the group and in 1827 they were joined byJoseph von Führich(1800–76).[37]In Rome the group lived a semi-monastic existence, as a way of re-creating the nature of the medieval artist's workshop. Religious subjects dominated their output and two major commissions for the Casa Bartholdy (1816–17) (later moved to the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin) and the Casino Massimo (1817–29), allowed them to attempt a revival of the medieval art offrescopainting and gained then international attention.[39]However, by 1830 all except Overbeck had returned to Germany and the group had disbanded. Many Nazareners became influential teachers in German art academies and were a major influence on the later EnglishPre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.[37]

Social commentary[edit]

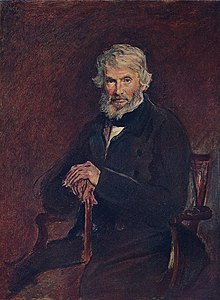

Eventually, medievalism moved from the confines of fiction into the immediate realm of social commentary as a means of critiquing life in theIndustrial Era.An early work of this kind isWilliam Cobbett'sHistory of the Protestant Reformation(1824–6), which was influenced by his reading ofJohn Lingard'sHistory of England(1819–30), among other sources. Cobbett attacked the Reformation as having divided a once-unified and wealthy England into "masters and slaves, a very few enjoying the extreme of luxury, and millions doomed to the extreme of misery", while decrying how "this land of meat and beef was changed, all of a sudden into a land of dry bread and oatmeal porridge".[40]In theVictorian era,the principal representatives of this school wereThomas Carlyleand his discipleJohn Ruskin.[41]

In Carlyle'sPast and Present(1843), whichOliver Eltoncalled the "most remarkable fruit in English literature of the medieval revival",[42]the modern workhouse is contrasted with the medieval monastery. He draws onJocelyn de Brakelond's twelfth-century account ofSamson of Tottington'sabbotcyofBury St Edmunds Abbeyto answer the "Condition-of-England Question",calling for a"Chivalryof Labour "based on cooperation and fraternity rather than competition and" Cash-payment for the sole nexus ", and for the leadership of paternalistic"Captains of Industry".[43]

Along with medievalist writersWalter Scott,Robert Southey,andKenelm Henry Digby,Carlyle was among the "important literary influences" onYoung England,a "parliamentary experiment in romanticism which created considerable stir during the eighteen-forties," led byLord John MannersandBenjamin Disraeli.[44]Young England developed contemporaneously with theOxford Movement,which has been defined as "medievalism in religion."[45]

Ruskin connected the quality of a nation's architecture with its spiritual health, comparing the originality and freedom of medieval art with the mechanistic sterility of modernism in such works asModern Painters,Volume II (1846),The Seven Lamps of Architecture(1849) andThe Stones of Venice(1851–3).[46]At the urging of Carlyle,[47]Ruskin, who identified as both a "violentToryof the old school "[48]and a "Communist of the old school",[49]adapted this thesis to his theory ofpolitical economyinUnto This Last(1860), and to his "Ideal Commonwealth" inTime and Tide(1867), the characteristics of which were derived from the Middle Ages: theguild system,the feudal system, chivalry, and the church.[50]

The Pre-Raphaelites[edit]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group ofEnglishpainters,poets,and critics, founded in 1848 byWilliam Holman Hunt,John Everett MillaisandDante Gabriel Rossetti.[51]The three founders were soon joined byWilliam Michael Rossetti,James Collinson,Frederic George StephensandThomas Woolnerto form a seven-member "brotherhood".[52]The group's intention was to reform art by rejecting what they considered to be the mechanistic approach first adopted by theManneristartists who succeededRaphaelandMichelangelo.[51]They believed that theClassicalposes and elegant compositions of Raphael in particular had been a corrupting influence on theacademicteaching of art. Hence the name "Pre-Raphaelite". In particular, they objected to the influence ofSir Joshua Reynolds,the founder of the EnglishRoyal Academy of Arts,believing that his broad technique was a sloppy and formulaic form of academic Mannerism. In contrast, they wanted to return to the abundant detail, intense colours, and complex compositions ofQuattrocentoItalian and Flemish art.[53]

The arts and crafts movement[edit]

The arts and crafts movement was an aesthetic movement, directly influenced by the Gothic revival and the Pre-Raphaelites, but moving away from aristocratic, nationalist and high Gothic influences to an emphasis on the idealised peasantry and medieval community, particularly of the fourteenth century, often withsocialistpolitical tendencies and reaching its height between about 1880 and 1910. The movement was inspired by the writings ofCarlyleand Ruskin and was spearheaded by the work ofWilliam Morris,a friend of the Pre-Raphaelites and a former apprentice to Gothic-revival architect G. E. Street. He focused on the fine arts of textiles, wood and metal work and interior design.[54]Morris also produced medieval and ancient themed poetry, beside socialist tracts and the medievalUtopiaNews From Nowhere(1890).[54]Morris formedMorris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.in 1861, which produced and sold furnishings and furniture, often with medieval themes, to the emerging middle classes.[55]The first arts and crafts exhibition in the United States was held in Boston in 1897 and local societies spread across the country, dedicated to preserving and perfecting disappearing craft and beautifying house interiors.[56]Whereas the Gothic revival had tended to emulate ecclesiastical and military architecture, the arts and crafts movement looked to rustic and vernacular medieval housing.[57]The creation of aesthetically pleasing and affordable furnishings proved highly influential on subsequent artistic and architectural developments.[58]

Romantic nationalism[edit]

By the nineteenth century real and pseudo-medieval symbols were a currency of Europeanmonarchical statepropaganda. German emperors dressed up in and proudly displayed medieval costumes in public, and they rebuilt the great medieval castle and spiritual home of theTeutonic Order at Marienburg.[59]Ludwig II of Bavariabuilt a fairy-tale castle atNeuschwansteinand decorated it with scenes fromWagner's operas, another major Romantic image maker of the Middle Ages.[60]The same imagery would be used inNazi Germanyin the mid-twentieth century to promote German national identity with plans for extensive building in the medieval style and attempts to revive the virtues of theTeutonic knights,Charlemagneand theRound Table.[61]

In England, the Middle Ages were trumpeted as the birthplace of democracy because of theMagna Cartaof 1215.[62]In the reign ofQueen Victoriathere was considerable interest in things medieval, particularly among the ruling classes. The notoriousEglinton Tournament of 1839attempted to revive the medieval grandeur of the monarchy and aristocracy.[63]Medieval fancy dress became common in this period at royal and aristocraticmasqueradesandballsand individuals and families were painted in medieval costume.[64]These trends inspired a nineteenth-century genre of medieval poetry that includedIdylls of the King(1842) byAlfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennysonand "The Sword of Kingship" (1866) by Thomas Westwood, which recast specifically modern themes in the medieval settings of Arthurian romance.[65][66]

Twentieth and twenty-first centuries[edit]

Popular culture[edit]

Depictions of the Middle Ages can be found in different cultural media, including advertising.[67]

Film[edit]

Film has been one of the most significant creators of images of the Middle Ages since the early twentieth century. The first medieval film was also one of the earliest films ever made, aboutJeanne d'Arcin 1899, while the first to deal withRobin Hooddates to as early as 1908.[68]Influential European films, often with a nationalist agenda, included the GermanNibelungenlied(1924),Eisenstein'sAlexander Nevsky(1938) andBergman'sThe Seventh Seal(1957), while in France there were many Joan of Arc sequels.[69]Hollywoodadopted the medieval as a major genre, issuing periodic remakes of theKing Arthur,William WallaceandRobin Hoodstories, adapting to the screen such historical romantic novels asIvanhoe(1952—byMGM), and producingepicsin the vein ofEl Cid(1961).[70]More recent revivals of these genres includeRobin Hood Prince of Thieves(1991),The 13th Warrior(1999) andThe Kingdom of Heaven(2005).[71]

Fantasy[edit]

While the folklore that fantasy drew on for its magic and monsters was not exclusively medieval, elves, dragons, and unicorns, among many other creatures, were drawn from medieval folklore andromance.Earlier writers in the genre, such asGeorge MacDonaldinThe Princess and the Goblin(1872),William MorrisinThe Well at the World's End(1896) andLord DunsanyinThe King of Elfland's Daughter(1924), set their tales infantasy worldsclearly derived from medieval sources, though often filtered through later views.[72]In the first half of the twentieth centurypulp fictionwriters likeRobert E. HowardandClark Ashton Smithhelped popularise thesword and sorcerybranch of fantasy, which often utilised prehistoric and non-European settings beside elements of the medieval.[73]In contrast, authors such asE. R. Eddisonand particularlyJ.R.R. Tolkien,set the type forhigh fantasy,normally based in apseudo-medievalsetting, mixed with elements of medieval folklore.[74]Other fantasy writers have emulated such elements, and films,role-playingandcomputer gamesalso took up this tradition.[75]Modern fantasy writers have taken elements of the medieval from these works to produce some of the most commercially successful works of fiction of recent years, sometimes pointing to the absurdities of the genre, as inTerry Pratchett'sDiscworldnovels, or mi xing it with the modern world as inJ. K. Rowling'sHarry Potterbooks.[76]

Living history[edit]

In the second half of the twentieth century interest in the medieval was increasingly expressed through form of re-enactment, includingcombat reenactment,re-creating historical conflict, armour, arms and skill, as well asliving historywhich re-creates the social and cultural life of the past, in areas such as clothing, food and crafts. The movement has led to the creation of medieval markets andRenaissance fairs,from the late 1980s, particularly in Germany and the United States of America.[77]

Neo-medievalism[edit]

Neo-medievalism (or neomedievalism) is aneologismthat was first popularized by the Italian medievalistUmberto Ecoin his 1973 essay "Dreaming of the Middle Ages".[78]The term has no clear definition but has since been used to describe the intersection between popular fantasy andmedieval historyas can be seen incomputer gamessuch asMMORPGs,filmsandtelevision,neo-medieval music,and popularliterature.[79]It is in this area—the study of the intersection between contemporary representation and past inspiration(s)—thatmedievalismandneomedievalismtend to be used interchangeably.[80]Neomedievalismhas also been used as a term describing thepost-modernstudy of medieval history[81]and as a term for a trend in moderninternational relations,first discussed in 1977 byHedley Bull,who argued that society was moving towards a form of "neomedievalism" in which individual notions of rights and a growing sense of a "world common good" were underminingnationalsovereignty.[82]

The study of medievalism[edit]

Leslie J. Workman,Kathleen Verduin and David Metzger noted in their introduction toStudies in MedievalismIX "Medievalism and the Academy, Vol I" (1997) their sense that medievalism had been perceived by some medievalists as a "poor and somewhat whimsical relation of (presumably more serious)medieval studies".[83]InThe Cambridge Companion to Medievalism(2016), editor Louise D'Arcens noted that some of the earliest medievalism scholarship (that is, study of the phenomenon of medievalism) was by Victorian specialists including Alice Chandler (with her monographA Dream of Order: The Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth Century England(London: Taylor and Francis, 1971), and Florence Boos, with her edited volumeHistory and Community: Essays in Victorian Medievalism(London: Garland Publishing, 1992)).[2]D'Arcens proposed that the 1970s saw the discipline of medievalism become an academic area of research in its own right, with theInternational Society for the Study of Medievalismformalised in 1979 with the publication of itsStudies In Medievalismjournal, organised by Leslie J. Workman.[2]D'Arcens notes that by 2016 medievalism was taught as a subject on "hundreds" of university courses around the world, and there were "at least two" scholarly journals dedicated to medievalism studies:Studies in Medievalismandpostmedieval.[2]

Clare Monagle has argued that political medievalism has caused medieval scholars to repeatedly reconsider whether medievalism is a part of the study of the Middle Ages as a historical period. Monagle explains how in 1977 the International Relations scholarHedley Bullcoined the term "New Medievalism"to describe the world as a result of the rising powers ofnon-state actorsin society (such as terrorist groups, corporations, or supra-state organisations such as the European Economic Community) which, due to new technologies, boundaries of jurisdiction that cross national borders, and shifts in private wealth challenged the exclusive authority of the state.[84]Monagle explained that in 2007 medieval scholarBruce HolsingerpublishedNeomedievalism, Conservativism and theWar on Terror,which identified howGeorge W. Bush's administration relied on medievalising rhetoric to identifyal-Qaedaas "dangerously fluid, elusive, and stateless".[84]Monagle documents howGabrielle Spiegel,then president of theAmerican Historical Society"expressed concern at the idea that scholars of the historical medieval period might consider themselves licensed to in some way to intervene in contemporary medievalism", as to do so "conflates two very different historical periods".[84]Eileen Joy (co-founder and co-editor of thepostmedievaljournal),[85]responded to Spiegel that "the idea of a medieval past itself, as something that can be demarcated and cordoned off from other historical time periods, was and is of itself [...] a form of medievalism. Therefore, practising medievalists should absolutely pay heed to the use and abuse of the Middle Ages in contemporary discourse".[84]

Medievalism topics are now annual features at the major medieval conferences theInternational Medieval Congresshosted at the University of Leeds, UK, and theInternational Congress on Medieval Studiesat Kalamazoo, Michigan.[2]

Exhibitions about medievalism[edit]

- 30 January - 22 May 2013.New Medievalist visions,King's College London,Maughan Library.[86]

- October 16, 2018 - March 3, 2019.Juggling the Middle Ages,Dumbarton Oaks,Washington DC.Juggling the Middle Ages"explores the influence of the medieval world by focusing on this single story with a long-lasting impact",Le Jongleur de Notre DameorOur Lady’s Tumbler.[87][88][89]

Further reading[edit]

- Kegel, Paul L. (1970)."Henry Adams and Mark Twain: Two Views of Medievalism".Mark Twain Journal.15(3): 11–21.ISSN0025-3499.

Bibliography[edit]

- Chandler, Alice (1970).A Dream of Order: The Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth-Century English Literature.Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.ISBN9780803207042.

Notes[edit]

- ^J. Simpson; E. Weiner, eds. (1989). "Medievalism".Oxford English Dictionary(2nd ed.). Oxford:Oxford University Press.

- ^abcdeD'Arcens, Louise (2016-03-02).The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism.Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–10.ISBN978-1-316-54620-8.

- ^Kathleen Davis and Nadia Altschul, eds.Medievalisms in the Postcolonial World: The Idea of "the Middle Ages" Outside Europe(2009)

- ^Mommsen, Theodore E.(1942). "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'".Speculum.17(2). Cambridge MA:Medieval Academy of America:226–42.doi:10.2307/2856364.JSTOR2856364.S2CID161360211.

- ^C. Rudolph,A companion to medieval art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe(Wiley-Blackwell, 2006), p. 4.

- ^abAlbrow, Martin,The global age: state and society beyond modernity(1997), p. 205.

- ^Random House Dictionary(2010), "Mediaeval"

- ^F. Oakley,The medieval experience: foundations of Western cultural singularity(University of Toronto Press, 1988), pp. 1-4.

- ^R. D. Linder,The Reformation Era(Greenwood, 2008), p. 124.

- ^K. J. Christiano, W. H. Swatos and P. Kivisto,Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments(Rowman Altamira, 2002), p. 77.

- ^abR. Bartlett,Medieval Panorama(Getty Trust Publications, 2001), p. 12.

- ^S. J. Barnett,The Enlightenment and Religion: the Myths of Modernity(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), p. 213.

- ^abN. Yates,Liturgical Space: Christian Worship and Church Buildings in Western Europe 1500-2000(Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2008), p. 114,

- ^A. Chandler,A Dream of Order: the Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth-Century English Literature(London: Taylor & Francis, 1971), p. 184.

- ^abcM. Moffett, M. W. Fazio, L. Wodehouse,A World History of Architecture(2nd edn., Laurence King, 2003), pp. 429-41.

- ^M. Alexander,Medievalism: the Middle Ages in Modern England(Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 71-3.

- ^D. D. Volo,The Antebellum Period American popular culture Through History(Greenwood, 2004), p. 131.

- ^F. Botting,Gothic(CRC Press, 1996), pp. 1-2.

- ^S. T. Joshi,Icons of Horror and the Supernatural: an Encyclopedia of our Worst Nightmares(Greenwood, 2007), p. 250.

- ^S. T. Joshi,Icons of Horror and the Supernatural: an Encyclopedia of our Worst Nightmares, Volume 1(Greenwood, 2007), p. 350.

- ^A. L. Smith,American Gothic Fiction: an Introduction(Continuum, 2004), p. 79.

- ^D. David,The Cambridge Companion to the Victorian Novel(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), p. 186.

- ^S. Arata,Fictions of Loss in the Victorian Fin de Siècle(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 111.

- ^Momma, Haruko (2012).From Philology to English Studies: Language and Culture in the Nineteenth Century.Studies in English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.doi:10.1017/cbo9781139023412.ISBN978-0-521-51886-4.

- ^Brackmann, Rebecca (2023).Old English Scholarship in the Seventeenth Century.Woodbridge: DS Brewer.

- ^Davies, Joshua (2019). "Hengist and Horsa at Monticello: Human and Nonhuman Migration, Parahistory and American Anglo-Saxonism". In Overing, Gillian; Wiethaus, Ulrike (eds.).American/Medieval Goes North.V&R UniPress.

- ^abA. Chandler,A Dream of Order: the Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth-Century English Literature(London: Taylor & Francis, 1971), p. 4.

- ^abR. R. Agrawal, "The Medieval Revival and its Influence on the Romantic Movement",(Abhinav, 1990), p. 1.ISBN978-8170172628

- ^Perpinyà, Núria.Ruins, Nostalgia and Ugliness. Five Romantic perceptions of the Middle Ages and a spoonful of Game of Thrones and Avant-garde oddity.Berlin: Logos Verlag. 2014ISBN978-3-8325-3794-4

- ^C. S. Lewis,The Discarded Image(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964),ISBN0-521-47735-2,p. 9.

- ^A. Chandler,A Dream of Order: the Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth-century English Literature(London: Taylor & Francis, 1971), pp. 54-7.

- ^W. P. Gerritsen, A. G. Van Melle and T. Guest,A Dictionary of Medieval Heroes: Characters in Medieval Narrative Traditions and Their Afterlife in Literature, Theatre and the Visual Arts(Boydell & Brewer, 2000), p. 256.

- ^R. E. Chandler and K. Schwart,A New History of Spanish Literature(LSU Press, 2nd edn., 1991), p. 29.

- ^M. Alexander,Beowulf: a Verse Translation(London: Penguin Classics, 2nd edn., 2004), p. xviii.

- ^G. S. Burgess,The Song of Roland(London: Penguin Classics, 1990), p. 7.

- ^S. P. Sondrup and G. E. P. Gillespie,Nonfictional Romantic Prose: Expanding Borders(John Benjamins, 2004), p. 8.

- ^abcdeK. F. Reinhardt,Germany: 2000 years, Volume 2(Continuum, 1981), p. 491.

- ^A. Chandler,A Dream of Order: the Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth-Century English Literature(London: Taylor & Francis, 1971), p. 191.

- ^K. Curran,The Romanesque Revival: Religion, Politics, and Transnational Exchange(Penn State Press, 2003), p. 4.

- ^Chandler 1970,pp. 65–68.

- ^"medievalism".Oxford Reference.Retrieved2022-08-08.

- ^Chandler 1970,p. 138.

- ^Bennett, J. A. W. (1978)."Carlyle and the medieval past".Reading Medieval Studies.IV:3–18.ISSN0950-3129.

- ^Kegel, Charles H. (1961)."Lord John Manners and the Young England Movement: Romanticism in Politics".The Western Political Quarterly.14(3): 691–697.doi:10.2307/444286.ISSN0043-4078.

- ^Chandler 1970,p. 153.

- ^Chandler 1970,pp. 198–203.

- ^Cook and Wedderburn, 17.lxx.

- ^Cook and Wedderbun, 35:13

- ^Cook and Wedderbun, 27:116

- ^G., T. F. (1893)."John Ruskin".The Sewanee Review.1(4): 491–497.ISSN0037-3052.JSTOR27527781.

- ^abR. Cronin, A. Chapman and A. H. Harrison,A Companion to Victorian Poetry(Wiley-Blackwell, 2002), p. 305.

- ^J. Rothenstein,An Introduction to English Painting(I.B.Tauris, 2001), p. 115.

- ^S. Andres,The pre-Raphaelite art of the Victorian novel: narrative challenges to visual gendered boundaries(Ohio State University Press, 2004), p. 247.

- ^abF. S. Kleiner, 'Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History(13th edn., Cengage Learning EMEA, 2008), p. 846.

- ^C. Harvey and J. Press,William Morris: Design and Enterprise in Victorian Britain(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991), pp. 77-8.

- ^D. Shand-Tucci, and R. A. Cram,Boston Bohemia, 1881-1900: Ralph Adams Cram Life and Literature(University of Massachusetts Press, 1996), p. 174.

- ^V. B. Canizaro,Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition(Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), p. 196.

- ^John F. Pile,A History of Interior Design(2nd edn., Laurence King, 2005), p. 267.

- ^R. A. Etlin,Art, Culture, and Media Under the Third Reich(University of Chicago Press, 2002), p. 118.

- ^Lisa Trumbauer,King Ludwig's Castle: Germany's Neuschwanstein(Bearport, 2005).

- ^V. Ortenberg,In Search of the Holy Grail: the Quest for the Middle Ages(Continuum, 2006), p. 114.

- ^R. Chapman,The Sense of the Past in Victorian Literature(London: Taylor & Francis, 1986), pp. 36-7.

- ^I. Anstruther,The Knight and the Umbrella: An Account of the Eglinton Tournament - 1839(London: Geoffrey Bles, 1963), pp. 122-3.

- ^J. Banham and J. Harris,William Morris and the Middle Ages: a Collection of Essays, together with a Catalogue of Works Exhibited at the Whitworth Art Gallery, 28 September-8 December 1984(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984), p. 76.

- ^R. Cronin, A. Chapman and A. H. Harrison,A Companion to Victorian Poetry(Wiley-Blackwell, 2002), p. 247.

- ^I. Bryden,Reinventing King Arthur: the Arthurian Legends in Victorian Culture(Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005), p. 79.

- ^Examples for the depiction of the Middle Ages in advertising (includinggender stereotypes): Megan Arnott (2019-01-31):“Viking Tough”: How Ads Sell Us Medieval Manhood.The Public Medievalist.Retrieved 2024-01-15.

- ^T. G. Hahn,Robin Hood in Popular Culture: Violence, Transgression, and Justice(Boydell & Brewer, 2000), p. 87.

- ^Norris J. Lacy,A History of Arthurian Scholarship(Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2006), p. 87.

- ^S. J. Umland,The Use of Arthurian Legend in Hollywood Film: from Connecticut Yankees to Fisher Kings(Greenwood, 1996), p. 105.

- ^N. Haydock and E. L. Risden,Hollywood in the Holy Land: Essays on Film Depictions of the Crusades and Christian-Muslim Clashes(McFarland, 2009), p. 187.

- ^R. C. Schlobin,The Aesthetics of Fantasy Literature and Art(University of Notre Dame Press, 1982), p. 236.

- ^J. A. Tucker,A Sense of Wonder: Samuel R. Delany, Race, Identity and Difference (Wesleyan University Press, 2004), p. 91.

- ^Jane Yolen, "Introduction",After the King: Stories in Honor of J. R. R. Tolkien,ed, Martin H. Greenberg, pp. vii-viii.ISBN0-312-85175-8.

- ^D. Mackay,The Fantasy Role-Playing Game: a New Performing Art(McFarland, 2001),ISBN978-0786450473,p. 27.

- ^Michael D. C. Drout,J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment(Taylor & Francis, 2007),ISBN978-0415969420,p. 380.

- ^M. C. C. Adams,Echoes of War: A Thousand Years of Military History in Popular Culture(University Press of Kentucky, 2002), p. 2.

- ^Umberto Eco,"Dreaming of the Middle Ages," inTravels in Hyperreality,transl. by W. Weaver (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1986), pp. 61–72. Eco wrote, "Thus we are at present witnessing, both in Europe and America, a period of renewed interest in the Middle Ages, with a curious oscillation between fantastic neomedievalism and responsible philological examination."

- ^M. W. Driver and S. Ray, eds,The medieval hero on screen: representations from Beowulf to Buffy(McFarland, 2004).

- ^J. Tolmie, "Medievalism and the Fantasy Heroine",Journal of Gender Studies,vol. 15, No. 2 July 2006, pp. 145–58

- ^Cary John Lenehan."Postmodern Medievalism",University of Tasmania,November 1994.

- ^K. Alderson andA. Hurrell,eds,Hedley Bull on International Society(London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000), p. 56.

- ^Workman, Leslie J.; Verduin, Kathleen; Metzger, David; Metzger, David D. (1999).Medievalism and the Academy.Boydell & Brewer. p. 2.ISBN978-0-85991-532-8.

- ^abcdMonagle, Clare (2014-04-18)."Sovereignty and Neomedievalism".In D'arcens, Louise; Lynch, Andrew (eds.).International Medievalism and Popular Culture.Cambria Press.ISBN978-1-60497-864-3.

- ^"A word from the co-editor of postmedieval, Eileen A. Joy".palgrave.Retrieved2020-11-08.

- ^"New Medievalist visions Exhibition at the Maughan Library | Website archive | King's College London".kcl.ac.uk.Retrieved2020-10-24.

- ^Wilson, Lain."Juggling the Middle Ages".Dumbarton Oaks.Retrieved2020-10-24.

- ^Nguyen, Sophia (2018-10-18)."The Juggler's Tale".Harvard Magazine.Retrieved2020-10-24.

- ^Dame, Marketing Communications: Web | University of Notre."D.C. museum tells an old Notre Dame story | Stories | Notre Dame Magazine | University of Notre Dame".Notre Dame Magazine.Retrieved2020-10-24.