Mohawk people

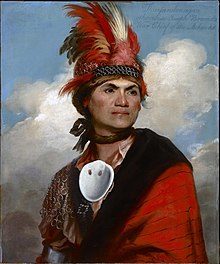

ThayendanegeaorJoseph Brant,byGilbert Stuart(1786) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Canada (Quebec,Ontario) | 33,330[1] |

| United States (New York) | 5,632 |

| Languages | |

| English,Mohawk,French, Formerly:Dutch,Mohawk Dutch | |

| Religion | |

| Karihwiio,Kanohʼhonʼio,Kahniʼkwiʼio,Christianity,Longhouse,Handsome Lake,OtherIndigenous Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Seneca Nation of New York,Oneida Nation of Wisconsin,Cayuga Nation of New York,Onondaga Nation,Tuscarora Nation,otherIroquoianpeoples | |

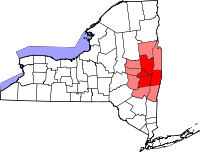

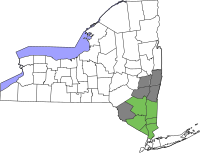

TheKanien'kehá:ka(transl."People of the flint";[2]commonly known inEnglishasMohawkpeople) are in the easternmost section of theHaudenosaunee,or Iroquois Confederacy. They are anIroquoian-speakingIndigenous peopleofNorth America,with communities in southeasternCanadaand northernNew York State,primarily aroundLake Ontarioand theSt. Lawrence River.As one of the five original members of theIroquois League,the Mohawk are known as theKeepers of the Eastern Door– the traditional guardians of the Iroquois Confederation against invasions from the east. The Mohawk are federally recognized in the United States as theSaint Regis Mohawk Tribe.[3]

At the time of European contact the Mohawk people were based in the valley of theMohawk Riverin present-day upstate New York, west of theHudson River.Their territory ranged north to theSt. Lawrence River,southernQuebecand easternOntario;south to greaterNew Jerseyand into Pennsylvania; eastward to theGreen MountainsofVermont;and westward to the border with the IroquoianOneida Nation's traditional homeland territory.

Kanienʼkehá:ka communities[edit]

Members of the Kanienʼkehá:ka people now live in settlements in northern New York State and southeastern Canada.

Many Kanienʼkehá:ka communities have two sets of chiefs, who are in some sense competing governmental rivals. One group are the hereditary chiefs (royaner), nominated byClan Mothermatriarchsin the traditional Mohawk fashion. Mohawks of most of the reserves have established constitutions with elected chiefs and councilors, with whom the Canadian and U.S. governments usually prefer to deal exclusively. The self-governing communities are listed below, grouped by broad geographical cluster, with notes on the character ofcommunity governancefound in each.

- Northern New York:

- Kanièn:ke(Ganienkeh) "Place of the flint". Traditional governance.

- Kanaʼtsioharè:ke"Place of the washed pail". Traditional governance.

- Along the St Lawrence in Quebec:

- Ahkwesáhsne(St. Regis, New York and Quebec/Ontario, Canada) "Where the partridge drums". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Kahnawà:ke(south of Montréal) "On the rapids". Canada, traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Kanehsatà:ke(Oka) "Where the snow crust is". Canada, traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Tioweró:ton(Sainte-Lucie-des-Laurentides, Quebec). Canada, shared governance between Kahnawà꞉ke and Kanehsatà꞉ke.

- Southern Ontario:

- Kenhtè꞉ke(Tyendinaga) "On the bay". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Wáhta(Gibson) "Maple tree". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Ohswé:ken"Six Nations of the Grand River". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections. Mohawks form the majority of the population of this Iroquois Six Nations reserve. There are also MohawkOrange Lodgesin Canada.

Given increased activism for land claims, a rise in tribal revenues due to establishment of gaming on certain reserves or reservations, competing leadership, traditional government jurisdiction, issues of taxation, and the CanadianIndian Act,Mohawk communities have been dealing with considerable internal conflict since the late 20th century.

History[edit]

First contact with European settlers[edit]

In theMohawk language,the Mohawk people call themselves the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka ( "people of the flint" ). The Mohawk became wealthy traders as other nations in their confederacy needed their flint for tool making. TheirAlgonquian-speaking neighbors (and competitors), the people ofMuh-heck Haeek Ing( "food area place" ), theMohicans,referred to the people of Ka-nee-en Ka asMaw Unk Lin,meaning "bear people". The Dutch heard and wrote this term asMohawk,and also referred to the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka asEgilorMaqua.

TheFrenchcolonists adapted these latter terms asAignierandMaqui,respectively. They also referred to the people by the genericIroquois,a French derivation of theAlgonquianterm for the Five Nations, meaning "Big Snakes". The Algonquians and Iroquois were traditional competitors and enemies.

In the upper Hudson and Mohawk Valley regions, the Mohawks long had contact with the Algonquian-speakingMohicanpeople who occupied territory along the Hudson, as well as other Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples to the north around theGreat Lakes.The Mohawks had extended their own influence into theSt. Lawrence RiverValley, which they maintained for hunting grounds. They are believed to have defeated theSt. Lawrence Iroquoiansin the 16th century, and kept control of their territory. In addition to hunting and fishing for centuries the Mohawks cultivated productive maize fields on the fertile floodplains along the Mohawk River, west of thePine Bush.

On June 28, 1609, a band of Hurons ledSamuel De Champlainand his crew into Mohawk country, the Mohawks being completely unaware of this situation. De Champlain made it clear he wanted to strike the Mohawks down after their raids on the neighboring nations. On July 29, 1609, hundreds of Hurons and many of De Champlain's French crew fell back from the mission, daunted by what lay ahead. Sixty Huron Indians, De Champlain, and two Frenchmen saw some Mohawks in a lake nearTiconderoga;the Mohawks spotted them as well. De Champlain and his crew fell back, then advanced to the Mohawk barricade after landing on a beach. They met the Mohawks at the barricade; 200 warriors advanced behind four chiefs. They were equally astonished to see each other -- De Champlain surprised at their stature, confidence, and dress; the Mohawks surprised by De Champlain's steelcuirassand helmet. One of the chiefs raised his bow at Champlain and the Indians. Champlain fired three shots that pierced the Mohawk chiefs' wooden armor, killing them instantly. The Mohawks stood in shock until they started flinging arrows at the crowd. A brawl began and the Mohawks fell back seeing the damage this new technology dealt on their chiefs and warriors. This was the first contact the Mohawks had withEuropeans.This incident also sparked theBeaver Wars.

Beaver Wars[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(September 2022) |

In the seventeenth century, the Mohawk encountered both theDutch,who went up theHudson Riverand established a trading post in 1614 at the confluence of the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers, and the French, who came south into their territory from New France (present-day Quebec). The Dutch were primarily merchants and the French also conductedfur trading.During this time the Mohawk fought with the Huron in the Beaver Wars for control of the fur trade with the Europeans. TheirJesuitmissionarieswere active amongFirst Nationsand Native Americans, seeking converts toCatholicism.

In 1614,the Dutchopened atrading postatFort Nassau,New Netherland.The Dutch initially traded for furs with the local Mohican, who occupied the territory along the Hudson River. Following a raid in 1626 when the Mohawks resettled along the south side of the Mohawk River,[4]: pp.xix–xx in 1628, they mounted an attack against the Mohican, pushing them back to the area of present-dayConnecticut.The Mohawks gained a near-monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch by prohibiting the nearby Algonquian-speaking peoples to the north or east to trade with them but did not entirely control this.

European contact resulted in a devastatingsmallpoxepidemic among the Mohawk in 1635; this reduced their population by 63%, from 7,740 to 2,830, as they had noimmunityto the new disease. By 1642 they had regrouped from four into three villages, recorded by Catholic missionary priestIsaac Joguesin 1642 asOssernenon,Andagaron,andTionontoguen,all along the south side of the Mohawk River from east to west. These were recorded by speakers of other languages with different spellings, and historians have struggled to reconcile various accounts, as well as to align them witharcheologicalstudies of the areas. For instance,Johannes Megapolensis,a Dutch minister, recorded the spelling of the same three villages as Asserué, Banagiro, and Thenondiogo.[4]Late 20th-century archeological studies have determined that Ossernenon was located about 9 miles west of the current city of Auriesville; the two were mistakenly conflated by a tradition that developed in the late 19th century in the Catholic Church.[5][6]

While the Dutch later established settlements in present-daySchenectadyandSchoharie,further west in the Mohawk Valley, merchants in Fort Nassau continued to control the fur trading. Schenectady was established essentially as a farming settlement, where the Dutch took over some of the former Mohawk maize fields in the floodplain along the river. Through trading, the Mohawk and Dutch became allies of a kind.

During their alliance, the Mohawks allowed Dutch Protestant missionaryJohannes Megapolensisto come into their communities and teach the Christian message. He operated from the Fort Nassau area for about six years, writing a record in 1644 of his observations of the Mohawk, their language (which he learned), and their culture. While he noted their ritual of torture of captives, he recognized that their society had few other killings, especially compared to the Netherlands of that period.[7][8]

The trading relations between the Mohawk and Dutch helped them maintain peace even during the periods ofKieft's Warand theEsopus Wars,when the Dutch fought localized battles with other native peoples. In addition, Dutch trade partners equipped the Mohawk with guns to fight against other First Nations who were allied with theFrench,including theOjibwe,Huron-Wendat,andAlgonquin.In 1645, the Mohawk made peace for a time with the French, who were trying to keep a piece of the fur trade.[9]

During thePequot War(1634–1638), thePequotand other Algonquian Indians of coastal New England sought an alliance with the Mohawks against English colonists of that region. Disrupted by their losses to smallpox, the Mohawks refused the alliance. They killed the PequotsachemSassacuswho had come to them for refuge, and returned part of his remains to the English governor of Connecticut,John Winthrop,as proof of his death.[10]

In the winter of 1651, the Mohawk attacked on the southeast and overwhelmed the Algonquian in the coastal areas. They took between 500 and 600 captives. In 1664, the Pequot of New England killed a Mohawk ambassador, starting a war that resulted in the destruction of the Pequot, as the English and their allies in New England entered theconflict,trying to suppress the Native Americans in the region. The Mohawk also attacked other members of the Pequot confederacy, in a war that lasted until 1671.[citation needed]

In 1666, the French attacked the Mohawk in the centralNew Yorkarea, burning the three Mohawk villages south of the river and their stored food supply. One of the conditions of the peace was that the Mohawk acceptJesuitmissionaries. Beginning in 1669, missionaries attempted to convert Mohawks to Christianity, operating a mission in Ossernenon 9 miles west[5][6]of present-dayAuriesville, New Yorkuntil 1684, when the Mohawks destroyed it, killing several priests.

Over time, some converted Mohawk relocated to Jesuit mission villages established south of Montreal on the St. Lawrence River in the early 1700s:Kahnawake(used to be spelled asCaughnawaga,named for the village of that name in the Mohawk Valley) andKanesatake.These Mohawk were joined by members of other Indigenous peoples but dominated the settlements by number. Many converted to Roman Catholicism. In the 1740s, Mohawk and French set up another village upriver, which is known asAkwesasne.Today a Mohawk reserve, it spans the St. Lawrence River and present-day international boundaries to New York, United States, where it is known as theSt. Regis Mohawk Reservation.

Kateri Tekakwitha,born at Ossernenon in the late 1650s, has become noted as a Mohawk convert to Catholicism. She moved with relatives to Caughnawaga on the north side of the river after her parents' deaths.[4]She was known for her faith and a shrine was built to her in New York. In the late 20th century, she wasbeatifiedand wascanonizedin October 2012 as the first Native American Catholic saint. She is also recognized by the Episcopal and Lutheran churches.

After the fall of New Netherland to England in 1664, the Mohawk in New York traded with the English and sometimes acted as their allies. DuringKing Philip's War,Metacom,sachemof the warringWampanoagPokanoket,decided to winter with his warriors near Albany in 1675. Encouraged by the English, the Mohawk attacked and killed all but 40 of the 400 Pokanoket.[citation needed]

From the 1690s, Protestant missionaries sought to convert the Mohawk in the New York colony. Many werebaptizedwith English surnames, while others were given both first and surnames in English.

During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Mohawk andAbenakiFirst Nations in New England were involved in raids conducted by the French and English against each other's settlements duringQueen Anne's Warand other conflicts. They conducted a growing trade in captives, holding them for ransom. Neither of the colonial governments generally negotiated for common captives, and it was up to local European communities to raise funds to ransom their residents. In some cases, French and Abenaki raiders transported captives from New England to Montreal and the Mohawk mission villages. The Mohawk atKahnawakeadopted numerous young women and children to add to their own members, having suffered losses to disease and warfare. For instance, among them were numerous survivors of the more than 100 captives taken in theDeerfield raidin western Massachusetts. The minister of Deerfield was ransomed and returned to Massachusetts, but his daughter was adopted by a Mohawk family and ultimately assimilated and married a Mohawk man.[11]

During the era of theFrench and Indian War(also known as theSeven Years' War), Anglo-Mohawk partnership relations were maintained by men such as SirWilliam Johnsonin New York (for the British Crown),Conrad Weiser(on behalf of the colony ofPennsylvania), andHendrick Theyanoguin(for the Mohawk). Johnson called theAlbany Congressin June 1754, to discuss with the Iroquois chiefs repair of the damageddiplomatic relationshipbetween the British and the Mohawk, along with securing their cooperation and support in fighting the French,[12]in engagements in North America.

American Revolutionary War[edit]

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(September 2022) |

During the second and third quarters of the 18th century, most of the Mohawks in theProvince of New Yorklived along the Mohawk River atCanajoharie.A few lived atSchoharie,and the rest lived about 30 miles downstream at the Tionondorage Castle, also calledFort Hunter.These two major settlements were traditionally called the Upper Castle and the Lower Castle. The Lower Castle was almost contiguous with SirPeter Warren's Warrensbush. SirWilliam Johnson,the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, built his first house on the north bank of the Mohawk River almost opposite Warrensbush and established the settlement ofJohnstown.

The Mohawk were among the four Iroquois people that allied with the British during theAmerican Revolutionary War.They had a long trading relationship with the British and hoped to gain support to prohibit colonists from encroaching into their territory in the Mohawk Valley.Joseph Brantacted as a war chief and successfully led raids against British and ethnic German colonists in the Mohawk Valley, who had been given land by the British administration near the rapids at present-dayLittle Falls, New York.

A few prominent Mohawk, such as thesachemLittle Abraham(Tyorhansera) at Fort Hunter, remained neutral throughout the war.[13]Joseph Louis Cook(Akiatonharónkwen), a veteran of the French and Indian War and ally of the rebels, offered his services to the Americans, receiving an officer's commission from theContinental Congress.He ledOneidawarriors against the British. During this war, Johannes Tekarihoga was the civil leader of the Mohawk. He died around 1780.Catherine Crogan,a clan mother and wife of Mohawk war chiefJoseph Brant,named her brother Henry Crogan as the new Tekarihoga.

In retaliation for Brant's raids in the valley, the rebel colonists organizedSullivan's Expedition.It conducted extensive raids against other Iroquois settlements in central and western New York, destroying 40 villages, crops, and winter stores. Many Mohawk and other Iroquois migrated to Canada for refuge nearFort Niagara,struggling to survive the winter.

After the Revolution[edit]

After the American victory, the British ceded their claim to land in the colonies, and the Americans forced their allies, the Mohawks and others, to give up their territories in New York. Most of the Mohawks migrated to Canada, where the Crown gave them some land in compensation. The Mohawks at the Upper Castle fled toFort Niagara,while most of those at the Lower Castle went to villages nearMontreal.

Joseph Brant led a large group of Iroquois out of New York to what became the reserve of theSix Nations of the Grand River,Ontario.Brant continued as a political leader of the Mohawks for the rest of his life. This land extended 100 miles from the head of theGrand Riverto the head ofLake Eriewhere it discharges.[14]Another Mohawk war chief,John Deseronto,led a group of Mohawk to theBay of Quinte.Other Mohawks settled in the vicinity of Montreal and upriver, joining the established communities (now reserves) atKahnawake,Kanesatake,andAkwesasne.

On November 11, 1794, representatives of the Mohawk (along with the other Iroquois nations) signed theTreaty of Canandaiguawith the United States, which allowed them to own land there.

The Mohawks fought as allies of the British against the United States in theWar of 1812.

20th century to present[edit]

In 1971, theMohawk Warrior Society,also Rotisken’rakéhte in the Mohawk language, was founded inKahnawake.The duties of the Warrior Society are to use roadblocks, evictions, and occupations to gain rights for their people, and these tactics are also used among the warriors to protect the environment from pollution. The notable movements started by the Mohawk Warrior Society have been theOka Crisisblockades in 1990 and the Caledonia Ontario, Douglas Creek occupation of a construction site in summer of 2006.

On May 13, 1974, at 4:00 a.m, Mohawks from theKahnawakeandAkwesasnereservations repossessed traditional Mohawk land near Old Forge, New York, occupying Moss Lake, an abandoned girls camp. The New York state government attempted to shut the operation down, but after negotiation, the state offered the Mohawk some land in Miner Lake, where they have since settled.

The Mohawks have organized for more sovereignty at their reserves in Canada, pressing for authority over their people and lands. Tensions with theQuebec Provincialandnational governmentshave been strained during certain protests, such as theOka Crisisin 1990.

In 1993, a group of Akwesasne Mohawks purchased 322 acres of land in the Town ofPalatineinMontgomery County, New Yorkwhich they namedKanatsiohareke.It marked a return to their ancestral land.

Mohawk ironworkers in New York[edit]

Mohawks came from Kahnawake and other reserves to work in the construction industry inNew York Cityin the early through the mid-20th century. They had also worked in construction in Quebec. The men wereironworkerswho helped build bridges and skyscrapers, and who were called skywalkers because of their seeming fearlessness.[15]They worked from the 1930s to the 1970s on special labor contracts as specialists and participated in building theEmpire State Building.The construction companies found that the Mohawk ironworkers did not fear heights or dangerous conditions. Their contracts offered lower than average wages to the First Nations people and limitedlabor unionmembership.[16]About 10% of all ironworkers in the New York area are Mohawks, down from about 15% earlier in the 20th century.[17]

The work and home life of Mohawk ironworkers was documented inDon Owen's 1965National Film Board of CanadadocumentaryHigh Steel.[18]The Mohawk community that formed in a compact area ofBrooklyn,which they called "Little Caughnawaga", after their homeland, is documented in Reaghan Tarbell'sLittle Caughnawaga: To Brooklyn and Back,shown on PBS in 2008. This community was most active from the 1920s to the 1960s. The families accompanied the men, who were mostly fromKahnawake;together they would return to Kahnawake during the summers. Tarbell is from Kahnawake and was working as a film curator at theGeorge Gustav Heye Centerof theNational Museum of the American Indian,located in theformer Custom HouseinLower Manhattan.[19]

Since the mid-20th century, Mohawks have also formed their own construction companies. Others returned to New York projects. Mohawk skywalkers had built theWorld Trade Centerbuildings that were destroyed during theSeptember 11 attacks,helped rescue people from the burning towers in 2001, and helped dismantle the remains of the building afterwards.[20]Approximately 200 Mohawk ironworkers (out of 2,000 total ironworkers at the site) participated in rebuilding theOne World Trade Centerin Lower Manhattan. They typically drive the 360 miles from the Kahnawake reserve on the St. Lawrence River in Quebec to work the week in lower Manhattan and then return on the weekend to be with their families. A selection of portraits of these Mohawk ironworkers were featured in an online photo essay forTimeMagazinein September 2012.[21]

Contemporary issues[edit]

Casinos[edit]

Both the elected chiefs and the Warrior Society have encouraged gambling as a means of ensuring tribal self-sufficiency on the various reserves or Indian reservations. Traditional chiefs have tended to oppose gaming on moral grounds and out of fear of corruption and organized crime. Such disputes have also been associated with religious divisions: the traditional chiefs are often associated with the Longhouse tradition, practicing consensus-democratic values, while the Warrior Society has attacked that religion and asserted independence. Meanwhile, the elected chiefs have tended to be associated (though in a much looser and general way) withdemocratic,legislative and Canadian governmental values.

On October 15, 1993, GovernorMario Cuomoentered into the "Tribal-State Compact Between the St. Regis Mohawk First Nation and the State of New York". The compact allowed the Indigenous people to conduct gambling, including games such asbaccarat,blackjack,crapsandroulette,on the Akwesasne Reservation inFranklin Countyunder theIndian Gaming Regulatory Act(IGRA). According to the terms of the 1993 compact, the New York State Racing and Wagering Board, theNew York State Policeand the St. Regis Mohawk Tribal Gaming Commission were vested with gaming oversight. Law enforcement responsibilities fell under the state police, with some law enforcement matters left to the community. As required by IGRA, the compact was approved by theUnited States Department of the Interiorbefore it took effect. There were several extensions and amendments to this compact, but not all of them were approved by theU.S. Department of the Interior.

On June 12, 2003, theNew York Court of Appealsaffirmed the lower courts' rulings that Governor Cuomo exceeded his authority by entering into the compact absent legislative authorization and declared the compact void[22]On October 19, 2004, GovernorGeorge Patakisigned a bill passed by the State Legislature that ratified the compact as beingnunc pro tunc,with some additional minor changes.[23]

In 2008 the Mohawk Nation was working to obtain approval to own and operate acasinoinSullivan County, New York,atMonticello Raceway.The U.S. Department of the Interior disapproved this action although the Mohawks gained GovernorEliot Spitzer's concurrence, subject to the negotiation and approval of either an amendment to the current compact or a new compact. Interior rejected the Mohawks' application to take this land into trust.[24]

In the early 21st century, two legal cases were pending that related to Native American gambling and land claims in New York. The State of New York has expressed similar objections to the Dept. of Interior taking other land into trust for federally recognized 'tribes', which would establish the land as sovereign Native American territory, on which they might establish new gaming facilities.[25]The other suit contends that the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act violates theTenth Amendment to the United States Constitutionas it is applied in the State of New York. In 2010 it was pending in theUnited States District Court for the Western District of New York.[26]

Culture[edit]

Social organization[edit]

The main structures of social organization are the clans (ken'tara'okòn:'a). The number of clans vary among the Haudenosaunee; the Mohawk have three: Bear (Ohkwa:ri), Turtle (A'nó:wara), and Wolf (Okwaho).[27]Clans are nominally the descendants of a single female ancestor, with women possessing the leadership role. Each member of the same clan, across all the Six Nations, is considered a relative. Traditionally, marriages between people of the same clan are forbidden.[note 1]Children belong to their mother's clan.[28]

Religion[edit]

Traditional Mohawk religion is mostlyAnimist."Much of the religion is based on a primordial conflict between good and evil."[29]Many Mohawks continue to follow theLonghouse Religion.

In 1632 a band ofJesuitmissionaries now known as theCanadian Martyrsled byIsaac Jogueswas captured by a party of Mohawks and brought to Ossernenon (now Auriesville, New York). Jogues and company attempted to convert the Mohawks to Catholicism, but the Mohawks took them captive, tortured, abused and killed them.[30]Following their martyrdom, new French Jesuit missionaries arrived and many Mohawks were baptized into the Catholic faith. Ten years after Jogues' deathKateri Tekakwitha,the daughter of a Mohawk chief and Tagaskouita, a Roman Catholic Algonquin woman, was born in Ossernenon and later wascanonizedas the first Native Americansaint.Religion became a tool of conflict between the French and British in Mohawk country. TheReformedclergymanGodfridius Delliusalso preached among the Mohawks.[31]

Traditional dress[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(December 2012) |

Historically, the traditionalhairstyle of Mohawk men,and many men of the other groups of the Iroquois Confederacy, was to remove most of the hair from the head by plucking (not shaving) tuft by tuft of hair until all that was left was a smaller section, that was worn in a variety of styles, which could vary by community. The women wore their hair long, often dressed with traditionalbear grease,or tied back into a single braid.

In traditional dress women often went topless in summer and wore a skirt of deerskin. In colder seasons, women wore a deerskin dress. Men wore abreech clothof deerskin in summer. In cooler weather, they added deerskin leggings, a deerskin shirt, arm and knee bands, and carried a quill and flint arrow hunting bag. Women and men wore puckered-seam, ankle-wrap moccasins with earrings and necklaces made of shells. Jewelry was also created using porcupine quills such asWampumbelts. For headwear, the men would use a piece of animal fur with attached porcupine quills and features. The women would occasionally wear tiaras of beaded cloth. Later, dress after European contact combined some cloth pieces such as wool trousers and skirts.[32][33]

Marriage[edit]

The Mohawk Nation people have amatrilinealkinship system, with descent and inheritance passed through the female line. Today, the marriage ceremony may follow that of the old tradition or incorporate newer elements, but is still used by many Mohawk Nation marrying couples. Some couples choose to marry in the European mannerandthe Longhouse manner, with the Longhouse ceremony usually held first.[34]

Communities[edit]

Replicas of seventeenth-century longhouses have been built at landmarks and tourist villages, such asKanata Village,Brantford, Ontario,andAkwesasne's "Tsiionhiakwatha" interpretation village. Other Mohawk Nation Longhouses are found on the Mohawk territory reserves that hold the Mohawk law recitations, ceremonial rites, andLonghouse Religion(or "Code ofHandsome Lake"). These include:

- Ohswé꞉ken (Six Nations)[35]First Nation Territory, Ontario holds six Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Wáhta[36]First Nation Territory, Ontario holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kenhtè꞉ke (Tyendinaga)[37]First Nation Territory, Ontario holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Ahkwesásne[38]First Nation Territory, which straddles the borders of Quebec, Ontario and New York, holds two Mohawk Ceremonial Community Longhouses.

- Kaʼnehsatà꞉keFirst Nation Territory, Quebec holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouses.

- Kahnawà꞉ke[39]First Nation Territory, Quebec holds three Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kanièn꞉ke[40]First Nation Territory, New York State holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kanaʼtsioharà꞉ke[41]First Nation Territory, New York State holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

Notable Mohawk[edit]

- Tammy Beauvais,Mohawk fashion designer

- Beth Brant,Mohawk writer and poet

- Joseph Brant,Mohawk leader, British officer

- Molly Brant,Mohawk leader, sister of Joseph Brant

- Joseph Tehawehron David,Mohawk artist

- Esther Louise Georgette Deer,Mohawk dancer and singer

- Tracey Deer,Mohawk filmmaker

- John Deseronto,Mohawk chief

- Canaqueese,called Flemish Bastard, Mohawk chief

- Carla Hemlock,quilter, beadwork artist

- Donald "Babe" Hemlock,woodcarver, sculptor

- Hiawatha,Mohawk chief

- Karonghyontyeor Captain David Hill, Mohawk leader

- Kahn-Tineta Horn,activist

- Kaniehtiio Horn,film and television actress

- Waneek Horn-Miller,Olympic water polo player

- Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs,actress, writer, and director

- Sid Jamieson,lacrosse player, coach

- George Henry Martin Johnson,Mohawk chief and interpreter

- Pauline Johnson,writer

- Stan Jonathan,former NHL hockey player

- Dawn Martin-Hill,professor

- Derek Miller,singer-songwriter

- Patricia Monture-Angus,lawyer, activist, educator, and author.

- Alwyn Morris,Olympic K–2 1000m.

- Shelley Niro(b. 1954), filmmaker, photographer, and installation artist

- John Norton,Scottish born, adopted into the Mohawk First Nation and made an honorary "Pine Tree Chief"

- Richard Oakes,Mohawk activist

- Ots-Toch,wife of Dutch colonist Cornelius A. Van Slyck

- Alex Rice,actress

- Robbie Robertson,singer-songwriter,The Band

- August Schellenberg,actor

- Jay Silverheels,actor

- Skawennati,multimedia artist and curator

- Barbara Stanley,professor, writer/author, activist, and GSNEO Woman of Distinction 2012

- Taiaiake Alfred,professor and activist

- Kiawentiio Tarbell,actress, singer-songwriter, and visual artist

- Julian Taylor,rock singer (Staggered Crossing,Julian Taylor Band)[42]

- Hendrick TejonihokarawaMohawk chief of the Wolf Clan; one of the four kings to visit England to seeQueen Anneto ask for help fighting the French

- Saint Kateri Tekakwitha,"Lily of the Mohawks", a Catholic saint

- Mary Two-Axe Earley,women's rights activist

- Billy Two Rivers,professional wrestler

- Oronhyatekha,physician, Scholar

- Tom Wilson,rock singer (Junkhouse,Blackie and the Rodeo Kings,Lee Harvey Osmond)

- Herbert York,nuclear physicist; administrator

See also[edit]

- Iroquois Confederacy

- Iroquoian languages

- Kahnawake surnames

- Mohawk language

- Native Americans in the United States

- Native American tribe

- Oka Crisis

- The Flying Head

Notes[edit]

- ^"Within certain clans there may also be different types of one animal or bird. For example, the turtle clan has three different types of turtles, the wolf clan has three different types of wolves and the bear clan includes three different types of bears allowing for marriage within the clan as long as each belongs to a different species of the clan."[28]

References[edit]

- ^"Canada Census Profile 2021".Census Profile, 2021 Census.Statistics Canada Statistique Canada. 7 May 2021.Retrieved3 January2023.

- ^"HAUDENOSAUNEE GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS"(PDF).National Museum of the American Indian.2009.Retrieved6 May2024.

- ^"Meet the People".National Museum of the American Indian.Retrieved2024-05-16.

- ^abcSnow, Dean R.; Gehring, Charles T.; Starna, William A. (1996).In Mohawk Country.Syracuse University Press.ISBN0-8156-2723-8.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-12-31.Retrieved2016-10-11.

- ^abDonald A. Rumrill, "An Interpretation and Analysis of the Seventeenth Century Mohawk Nation: Its Chronology and Movements",The Bulletin and Journal of Archaeology for New York State,1985, vol. 90, pp. 1–39

- ^abDean R. Snow, (1995)Mohawk Valley Archaeology: The Sites,University at Albany Institute for Archaeological Studies (First Edition);Occasional Papers Number 23,Matson Museum of Anthropology, The Pennsylvania State University (Second Edition).

- ^"Dutch missionary John Megapolensis on the Mohawks (Iroquois), 1644".Smithsonian Source.Archived fromthe originalon June 11, 2016.RetrievedMay 27,2016.

- ^"A Short History of the Mohawk"Archived2016-06-24 at theWayback Machine,inIn Mohawk Country: Early Narratives about a Native People,ed. Dean R. Snow, Charles T. Gehring, William A. Starna; Syracuse University Press, 1996, pp. 38–46

- ^William N. Fenton, Francis Jennings, Mary A. Druke:The Earliest Recorded Description. The Mohawk Treaty withNew FranceatThree Rivers1645,in Jennings ed.,The History and Culture of Iroquois Diplomacy.Syracuse University Press,1985, pp. 127–153

- ^"General History of Duchess County, From 1609 to 1876, Inclusive", Philip H. Smith, Pawling, New York, 1877, p. 154

- ^John Demos,The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America,New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994

- ^"The Albany Congress".Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2014.Retrieved2 April2014.

- ^"Little Abraham Tyorhansera, Mohawk Indian, Wolf Clan Chief".Native Heritage Project.16 August 2012.Archivedfrom the original on July 1, 2016.RetrievedMay 26,2016.

- ^Stone, William (September 1838). "Life of Joseph Brant--Thayendanegea; including the Border Wars of the American Revolution".American Monthly Magazine.12:12, 273–284.

- ^Sky Walking: Raising Steel, A Mohawk Ironworker Keeps Tradition Alive,archivedfrom the original on 2016-11-01,retrieved2016-10-29

- ^Joseph Mitchell, "The Mohawks in High Steel", in Edmund Wilson,Apologies to the Iroquois(New York: Vintage, 1960), pp. 3–36.

- ^Nessen, Stephen (19 March 2012),Sky Walking: Raising Steel, A Mohawk Ironworker Keeps Tradition Alive,archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2016,retrieved2016-10-29

- ^Owen, Don."High Steel"(RequiresAdobe Flash).Online documentary.National Film Board of Canada.Archivedfrom the original on 28 December 2010.Retrieved14 March2011.

- ^Tarbell, Reaghan (2008)."Little Caughnawaga: To Brooklyn and Back".National Film Board of Canada.RetrievedAugust 31,2009.

- ^Wolf, White."The Mohawks Who Built Manhattan (Photos)".White Wolf.Archived fromthe originalon 2017-10-22.Retrieved2016-10-29.

- ^Wallace, Vaughn (2012-09-11)."The Mohawk Ironworkers: Rebuilding the Iconic Skyline of New York".Time.Archived fromthe originalon 2012-09-15.Retrieved2012-09-16.

- ^ROSENBLATT (12 June 2003)."3 No. 42: Saratoga County Chamber of Commerce Inc., et al. v. George Pataki, as Governor of the State of New York, et al".law.cornell.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2017.Retrieved27 June2017.

- ^see C. 590 of the Laws of 2004

- ^"The Associate Deputy Secretary of the Interior"(PDF).Washington. 4 January 2008.Archived(PDF)from the original on 27 March 2009.Retrieved29 October2010.

- ^"Former Website of the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 6 February 2007.Retrieved29 October2010.

- ^"Warren v. United States of America, et al".Archived fromthe originalon 1 August 2012.Retrieved29 October2010.

- ^"Mohawk Language Lessons 2017 Lesson 5 Clans".Kenhtè:ke nene kanyen’kehá:ka.RetrievedMay 10,2023.

- ^ab"Clan System".Haudenosaunee Confederacy.RetrievedMay 10,2023.

- ^"mohawk".Cultural Survival.Archivedfrom the original on May 28, 2015.RetrievedMay 26,2015.

- ^Anderson, Emma (2013).The Death and Afterlife of the North American Martyrs.Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 25.

- ^Corwin, Edward Tanjore (1902).A Manual of the Reformed Church in America (formerly Reformed Protestant Dutch Church). 1628-1902.Board of publication of the Reformed church in America. pp. 408–410.ISBN9780524060162.

- ^Inglish, Patty (February 27, 2020)."Traditional Mohawk Nation Daily and Ceremonial Clothing".Owlcation.Retrieved2020-08-10.

- ^Megapolensis, Jr., Johannes. "A Short Account of the Mohawk Indians."Short Account of the Mohawk Indians,August 2017, 168

- ^Anne Marie Shimony, "Conservatism among the Iroquois at Six Nations Reserve", 1961

- ^"Six Nations Of The Grand River".Archived fromthe originalon 2016-01-28.Retrieved2007-12-16.

- ^"Home Page".wahta.ca.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-03-27.Retrieved2019-03-27.

- ^"Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte – Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory » Home".Archived fromthe originalon 2007-09-28.Retrieved2007-12-16.

- ^"She꞉kon/Greetings – Mohawk Council of Akwesasne".Archived fromthe originalon 2007-12-26.Retrieved2007-12-16.

- ^Kahnawá:ke, Mohawk Council of."Mohawk Council of Kahnawá:ke".kahnawake.Archived fromthe originalon 2013-09-06.

- ^"— ganienkeh.net-- Information from the People of Ganienkeh".Archivedfrom the original on 2013-06-03.Retrieved2012-12-02.

- ^"Kanatsiohareke Mohawk Community".Archivedfrom the original on 2007-10-18.Retrieved2007-12-16.

- ^Madeline Crone,"Julian Taylor Premieres Title Track, 'The Ridge'".American Songwriter,April 8, 2020.

- Snow, Dean R.(1994).The Iroquois.Boston: Blackwell Publishers.ISBN1-55786-938-3.

- Dean R. Snow;William A. Starna;Charles T. Gehring, eds. (1996).In Mohawk Country: Early Narratives about a Native People.Syracuse University Press.ISBN9780815604105.

External links[edit]

- Culture of the HaudenosauneeArchived2019-04-14 at theWayback Machineon theMohawks of the Bay of Quintewebsite

- Akwesasne Newsat theAkwesasnewebsite

- The Wampum Chronicles: Mohawk Territoryarticles on history and culture

- "Mohawk Institute", Geronimo Henryarchived site

- Mohawk skyscraper builders and construction workers in New York City?

- The Iroquois Book of Rites by Horatio Hale,atProject Gutenberg

- Mohawk people

- Mohawk

- First Nations in Ontario

- First Nations in Quebec

- Native American history of New York (state)

- Native American history of Vermont

- Native American tribes in Vermont

- Native American tribes in New York (state)

- Native American tribes in Pennsylvania

- People from New Netherland

- Algonquian ethnonyms