Mule deer

| Mule deer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male (buck) nearElk Creek,Oregon | |

| |

| Female (doe) nearSwall Meadows,California | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Capreolinae |

| Genus: | Odocoileus |

| Species: | O. hemionus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Odocoileus hemionus Rafinesque,1817[2]

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

10, but some disputed (seetext) | |

| |

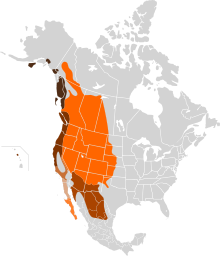

| Distribution map of subspecies:

Sitka black-tailed deer (O. h. sitkensis)

Columbian black-tailed deer (O. h. columbianus)

California mule deer (O. h. californicus)

southern mule deer (O. h. fuliginatus)

peninsular mule deer (O. h. peninsulae)

desert mule deer (O. h. eremicus)

Rocky Mountain mule deer (O. h. hemionus)

| |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

| |

Themule deer(Odocoileus hemionus) is adeerindigenous to westernNorth America;it is named for its ears, which are large like those of themule.Twosubspeciesof mule deer are grouped into theblack-tailed deer.[1][5][6][7][8][9]

Unlike the relatedwhite-tailed deer(Odocoileus virginianus), which is found throughout most of North America east of theRocky Mountainsand in the valleys of the Rocky Mountains fromIdahoandWyomingnorthward, mule deer are only found on the westernGreat Plains,in the Rocky Mountains, in thesouthwest United States,and on the west coast of North America. Mule deer have also been introduced toArgentinaandKauai, Hawaii.[5]

Taxonomy[edit]

Mule deer can be divided into two main groups: the mule deer (sensu stricto) and theblack-tailed deer.The first group includes all subspecies, exceptO. h. columbianusandO. h. sitkensis,which are in the black-tailed deer group.[5]The two main groups have been treated as separate species, but theyhybridize,and virtually all recent authorities treat the mule deer and black-tailed deer asconspecific.[1][5][6][7][9][10]Mule deer apparentlyevolvedfrom the black-tailed deer.[9]Despite this, themtDNAof the white-tailed deer and mule deer is similar, but differs from that of the black-tailed deer.[9]This may be the result ofintrogression,although hybrids between the mule deer and white-tailed deer are rare in the wild (apparently more common locally inWest Texas), and the hybridsurvival rateis low even in captivity.[8][9]Many claims of observations of wild hybrids are not legitimate, as identification based on external features is complicated.[8]

Subspecies[edit]

Some authorities have recognizedO. h. crookias asenior synonymofO. h. eremicus,but thetype specimenof the former is ahybridbetween the mule deer and white-tailed deer, so the nameO. h. crookiis invalid.[5][11]Additionally, the validity ofO. h. inyoensishas been questioned, and the twoinsularO. h. cerrosensisandO. h. sheldonimay besynonymsofO. h. eremicusorO. h. peninsulae.[10]

The 10 valid subspecies, based on the third edition ofMammal Species of the World,are:[5]

- Mule deer (sensu stricto) group:

- O. h. californicus–California mule deer.This widespread subspecies is found throughout much ofCalifornia(north ofSan DiegoandImperial), with high densities inOrangeandLos Angeles Countiesto coastalSanta Barbara,Ventura,andSan Luis Obispo;fromMorro BaytoSanta Cruz,along the coast, its range is somewhat patchier.[12]Inland, the California mule deer is known from aroundSan Bernardinoto as far north asLassen;many deer inhabit the areas in and aroundSequoia National Park,Yosemite,Plumas National Forest,and of course, theSierra Nevada,its range partly overlapping with that of the Inyo subspecies (O. h. inyoensis).[12]It is notably absent from theCentral Valleyand theagricultural districtsof the state (roughly betweenBakersfieldandSacramento); north of San Francisco, it is replaced by the Columbian subspecies (O. h. columbianus).[13]It is also known to range across the border into west-centralNevada,betweenRenoandCarson City.[14]

- O. h. cerrosensis–CedrosorCerros Island mule deer,afterCedros Island,off of the southwesternPacificcoast ofBaja California state,the subspecies' sole habitat.[15]

- O. h. eremicus–Desertorburro mule deer.Primarily found in theLower Colorado River Valley,Southern California'sInland Empire,the areas aroundLas Vegasand extreme southern Nevada, much ofArizonaand parts of southernNew Mexico.[16]InMexico,it is primarily known fromSonora,having been known from as far south asHermosillo;it has also been observed (somewhat out-of-range) inCoahuila,ChihuahuaandDurango.[17]

- O. h. fuliginatus–Southern mule deer.Mainly found in Southern California (Los Angeles, Orange and San Diego Counties) and along theU.S.-Mexico borderlands,into the northern half of theBaja California Peninsula,where it has been sighted as far south asEl Rosario.Notably high population densities occur to the west ofAnza-Borrego Desert State Park(in the San Diego County portion of theCleveland National Forest) and in and around the region ofJulian, California.[18][19]

- O. h. hemionus–Rocky Mountain mule deer.Primarily found in western and central North America, as far south as Colorado and as far north asYukonand theNorthwest Territories,including inlandBritish Columbia.

- O. h. inyoensis–Inyo mule deer(named afterInyo County, California). This deer is primarily found within the Sierra Nevada and Yosemite, within inlandCentral California,and has been sighted as far south asDeath Valleyand as far north as theStanislaus National Forest.[20]

- O. h. peninsulae–BajaorPeninsular mule deer;found across the majority of the state ofBaja California Sur,Mexico.[21]

- O. h. sheldoni–Tiburón Island mule deer,also called thevenado bura de Tiburónin Spanish. This deer is only found onTiburón Island,Mexico, in theGulf of California.[22]

- Black-tailed deer group:

- O. h. columbianus–Columbian black-tailed deer;found primarily in coastaltemperate rainforesthabitats of thePacific NorthwestandNorthern California(north of approx. the San FranciscoBay AreatoVancouver, BC)

- O. h. sitkensis–Sitka black-tailed deer(named afterSitka, Alaska); found in similar temperate rainforests as the Columbian subspecies—though with a more northerly range—from the central coast of British Columbia (includingHaida Gwaii) throughoutSoutheast Alaska(along theGulf of Alaska), with smaller populations further north toAnchorage,theKenai Peninsula,andKodiak Island.Found typically in dense, lush habitats, such as theGreat Bear RainforestandTongass National Forest.[23]

Description[edit]

The most noticeable differences between white-tailed and mule deer are ear size, tail color, and antler configuration. In many cases, body size is also a key difference. The mule deer's tail is black-tipped, whereas the white-tailed deer's is not. Mule deer antlers are bifurcated; they "fork" as they grow, rather than branching from a single main beam, as is the case with white-tails.

Each spring, a buck's antlers start to regrow almost immediately after the old antlers are shed. Shedding typically takes place in mid-February, with variations occurring by locale.

Although capable of running, mule deer are often seenstotting(also called pronking), with all four feet coming down together.

The mule deer is the larger of the threeOdocoileusspecies on average, with a height of 80–106 cm (31–42 in) at the shoulders and a nose-to-tail length ranging from 1.2 to 2.1 m (3.9 to 6.9 ft). Of this, the tail may comprise 11.6 to 23 cm (4.6 to 9.1 in). Adult bucks normally weigh 55–150 kg (121–331 lb), averaging around 92 kg (203 lb), although trophy specimens may weigh up to 210 kg (460 lb). Does (female deer) are smaller and typically weigh from 43 to 90 kg (95 to 198 lb), with an average of around 68 kg (150 lb).[24][25][26][27]

Unlike the white-tailed, the mule deer does not generally show marked size variation across its range, although environmental conditions can cause considerable weight fluctuations in any given population. An exception to this is theSitka deersubspecies (O. h. sitkensis). This race is markedly smaller than other mule deer, with an average weight of 54.5 kg (120 lb) and 36 kg (79 lb) in males and females, respectively.[28]

Seasonal behaviors[edit]

In addition to movements related to available shelter and food, the breeding cycle is important in understanding deer behavior. Therutor mating season usually begins in the fall as does go intoestrusfor a period of a few days, and males become more aggressive, competing for mates. Does may mate with more than one buck and go back into estrus within a month if they did not become pregnant. The gestation period is about 190–200 days, with fawns born in the spring.[29]The survival rate of the fawns during labor is about 50%.[30]Fawns stay with their mothers during the summer and are weaned in the fall after about 60–75 days. Mule deer females usually give birth to two fawns, although if it is their first time having a fawn, they often have just one.[29]

A buck's antlers fall off during the winter, then grow again in preparation for the next season's rut. The annual cycle of antler growth is regulated by changes in the length of the day.[29][31]

The size of mule deer groups follows a marked seasonal pattern. Groups are smallest during fawning season (June and July in Saskatchewan and Alberta) and largest in early gestation (winter; February and March in Saskatchewan and Alberta).[31]

Besides humans, the three leading predators of mule deer arecoyotes,wolves,andcougars.Bobcats,Canada lynx,wolverines,American black bears,andgrizzly bearsmay prey upon adult deer but most often attack only fawns or infirm specimens, or they may eat a deer after it has died naturally. Bears and small carnivores are typicallyopportunistic feedersand pose little threat to a strong, healthy mule deer.[25]

Diet and foraging behaviors[edit]

In 99 studies of mule deer diets, some 788 species of plants were eaten by mule deer, and their diets vary greatly depending on the season, geographic region, year, and elevation.[32]The studies[33]gave these data for Rocky Mountain mule deer diets:[34]

| Shrubs and trees | Forbs | Grasses and grass-like plants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | 74% | 15% | 11% (varies 0–53%) |

| Spring | 49% | 25% | 26% (varies 4–64%) |

| Summer | 49% | 46% (varies 3–77%) | 3% (varies 0–22%) |

| Fall | 60% | 30% (varies 2–78%) | 9% (varies 0–24%) |

The diets of mule deer are very similar to those of white-tailed deer in areas where they coexist.[35][32]Mule deer are intermediate feeders rather than purebrowsersorgrazers;they predominantly browse but also eatforbvegetation, small amounts of grass and, where available, tree or shrub fruits such asbeans,pods,nuts(includingacorns), andberries.[32][34]

Mule deer readily adapt to agricultural products and landscape plantings.[36][37]In theSierra Nevada range,mule deer depend on the lichenBryoria fremontiias a winter food source.[38]

The most common plant species consumed by mule deer are the following:

- Among trees and shrubs:Artemisia tridentata(big sagebrush),Cercocarpus ledifolius(curlleaf mountain mahogany),Cercocarpus montanus(true mountain mahogany),Cowania mexicana(Mexican cliffrose),Populus tremuloides(quaking aspen),Purshia tridentata(antelope bitterbrush),Quercus gambelii(Gambel oak), andRhus trilobata(skunkbush sumac).[34]

- Among forbs:Achillea millefolium(western yarrow),Antennaria(pussytoes) species,Artemisia frigida(fringed sagebrush),Artemisia ludoviciana(Louisiana sagewort),Asterspecies,Astragalus(milkvetch) species,Balsamorhiza sagittata(arrowleaf balsamroot),Cirsium(thistle) species,Erigeron(fleabane) species,Geraniumspecies,Lactuca serriola(prickly lettuce),Lupinus(lupine) species,alfalfa,Penstemonspecies,Phloxspecies,Polygonum(knotweed/smartweed) species,Potentilla(cinquefoil) species,Taraxacum officinale(dandelion),Tragopogon dubius(western salsify),clover,andVicia americana(American vetch).[34]

- Among grasses and grasslike species:Agropyron,Elymus(wheatgrasses),Elytrigia,Pascopyrumspecies (wheatgrasses),Pseudoroegneria spicatum(bluebunch wheatgrass),Bromus tectorum(cheatgrass),Carex(sedge) species,Festuca idahoensis(Idaho fescue),Poa fendleriana(muttongrass),Poa pratensis(Kentucky bluegrass), and otherPoa(bluegrass) species.[34]

Mule deer have also been known to eatricegrass,gramagrass,andneedlegrass,as well asbearberry,bitter cherry,black oak,California buckeye,ceanothus,cedar,cliffrose,cottonwood,creek dogwood,creeping barberry,dogwood,Douglas fir,elderberry,Fendleraspecies,goldeneye,holly-leaf buckthorn,jack pine,knotweed,Kohleriaspecies,manzanita,mesquite,pine,rabbitbrush,ragweed,redberry,scrub oak,serviceberry(includingPacific serviceberry),Sierra juniper,silktassel,snowberry,stonecrop,sunflower,tesota,thimbleberry,turbinella oak,velvet elder,western chokecherry,wild cherry,andwild oats.[39]Where available, mule deer also eat a variety of wildmushrooms,which are most abundant in late summer and fall in the southern Rocky Mountains; mushrooms provide moisture, protein, phosphorus, and potassium.[32][39]

Humans sometimes engage in supplemental feeding efforts in severe winters in an attempt to help mule deer avoid starvation. Wildlife agencies discourage such efforts, which cause harm to mule deer populations by spreading disease (such astuberculosisandchronic wasting disease) when deer congregate for feed, disrupting migratory patterns, causingoverpopulationof local mule deer populations, and causinghabitat destructionfrom overbrowsing of shrubs and forbs. Supplemental feeding efforts might be appropriate when carefully conducted under limited circumstances, but to be successful, the feeding must begin early in the severe winter (before poor range conditions and severe weather cause malnourishment or starvation) and must be continued until range conditions can support the herd.[40]

Mule deer are variably gregarious, with a large proportion of solitary individuals (35 to 64%) and small groups (groups with ≤5 deer, 50 to 78%).[41][42]Reported meangroup sizemeasurements are three to five and typical group size (i.e., crowding) is about seven.[31][43]

-

Mule deer foraging on a late winter morning atOkanagan Mountain Provincial Park

-

Male Rocky Mountain mule deer (O. h. hemionus) inZion National Park

-

MaleO. h. hemionusnearLeavenworth, Washington

-

Female Columbian black-tailed deer (O. h. columbianus) inOlympic National Park

-

Female mule deer in Garden of the Gods, Colorado Springs, Colorado, USA.

Nutrition[edit]

Mule deer areruminants,meaning they employ a nutrient acquisition strategy of fermenting plant material before digesting it. Deer consuming high-fiber, low-starch diets require less food than those consuming high-starch, low-fiber diets. Rumination time also increases when deer consume high-fiber, low-starch diets, which allows for increased nutrient acquisition due to greater length of fermentation.[44]Because some of the subspecies of mule deer are migratory, they encounter variable habitats and forage quality throughout the year.[45]Forages consumed in the summer are higher in digestible components (i.e. proteins, starches, sugars, andhemicellulose) than those consumed in the winter. The average gross energy content of the consumed forage material is 4.5kcal/g.[46]

Due to fluctuations in forage quality and availability, mule deer fat storage varies throughout the year, with the most fat stored in October, which is depleted throughout the winter to the lowest levels of fat storage in March. Changes in hormone levels are indications of physiological adjustments to the changes in the habitat. Total body fat is a measure of the individual's energy reserves, whilethyroid hormoneconcentrations are a metric to determine the deer's ability to use the fat reserves.Triiodothyronine(T3) hormone is directly involved withbasal metabolic rateand thermoregulation.[47]

Migration[edit]

Mule deer migrate from low elevation winter ranges to high elevation summer ranges.[48]Although not all individuals in populations migrate, some will travel long distances between summer and winter ranges.[49]Researchers discovered the longest mule deer migration in Wyoming spanning 150 miles from winter to summer range[48]Multiple US states track mule deer migrations.[50][51][52][53]

Mule deer migrate in fall to avoid harsh winter conditions like deep snow that covers up food resources, and in spring follow the emergence of new growth northwards.[54][55]There is evidence to suggest that mule deer migrate based on cognitive memory, meaning they use the same path year after year even if the availability of resources has changed. This contradicts the idea that animals will go to the areas with the best available resources, which makes migratory paths crucial for survival.[55]

Risks[edit]

There are many risks that mule deer face during migration including climate change and human disturbance. Climate change impacts on seasonal growth patterns constitute a risk for migrating mule deer by invalidating historic or learned migration paths.[56][57]

Human activities such as natural resource extraction, highways, fencing, and urban development all have an impact on mule deer populations and migrations through habitat degradation and fragmentation.[58][59][60][61]Natural gas extraction has been found to have varying negative effects on mule deer behavior and can even cause them to avoid areas they use to migrate.[58]Highways not only cause injury and death to mule deer, but they can also serve as a barrier to migration.[62]As traffic volumes increase, the more mule deer tend to avoid those areas and abandon their typical migration routes. It has also been found that fencing can alter deer behavior, acting as a barrier, and potentially changing mule deer migration patterns.[63]In addition, urban development has replaced mule deer habitat with subdivisions, and human activity has increased. As a result of this, researchers have seen a decline in mule deer populations. This is especially prominent in Colorado where the human population has grown by over 2.2 million since 1980.[61]

Management[edit]

Protecting migration corridors[edit]

Protecting migrations corridors is essential to maintain healthy mule deer populations. One thing everyone can do is help slow the increase in climate change by using greener energy sources and reducing the amount of waste in our households.[64]In addition, managers and researchers can assess the risks listed above and take the proper steps to mitigate any adverse impacts those risk have on mule deer populations. Not only will populations benefit from these efforts but so will many other wildlife species.[65]

Highways[edit]

One way to help protect deer from getting hit on roadways is to install high fence wildlife fencing with escape routes.[66]This helps keep deer off the road, preventing vehicle collisions and allowing animals that are trapped between the road and the fence a way to escape to safety.[66]However, to maintain migration routes that cross busy highways, managers have also implemented natural, vegetated, overpasses and underpasses to allow animals, like mule deer, to migrate and move safely across highways.[67]

Natural resource extraction[edit]

Approaches to mitigating the impact of drilling and mining operations include regulating the time of year when active drilling and heavy traffic to sites are taking place, and using well-informed planning to protect critical deer habitat and using barriers to mitigate the activity, noise, light at the extraction sites.[68]

Urban development[edit]

The increase in urbanization has impacted mule deer migrations and there is evidence to show it also disrupts gene flow among mule deer populations.[69]One clear option is to not build houses in critical mule deer habitat; however, build near mule deer habitat has resulted in some deer becoming accustom to humans and the resources, such as food and water.[70]Rather than migrate through urban areas some deer tend to stay close to those urban developments, potentially for resources and to avoid the obstacles in urban areas.[71]Suggested measures by property owners to protect mule deer genetic diversity and migration paths include planting deer-resistant plants, placing scare devices such as noise-makers, and desisting from feeding deer.[70]

Disease[edit]

Wildlife officials inUtahannounced that a November–December 2021 field study had detected the first case of SARS-CoV-2 in mule deer. Several deer possessed apparent SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, however a female deer inMorgan Countyhad an activeDelta variantinfection.[72]White-tailed deer,which are able to hybridize with mule deer and which have shown high rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection, have migrated into Morgan County and other traditional mule deer habitats since at least the early 2000s.[73][74]

References[edit]

- ^abcSanchez-Rojas, G.; Gallina-Tessaro, S. (2016)."Odocoileus hemionus".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2016:e.T42393A22162113.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T42393A22162113.en.Retrieved12 November2021.

- ^"Odocoileus hemionus".Integrated Taxonomic Information System.Retrieved23 March2006.

- ^Anderson, Allen E.; Wallmo, Olof C. (27 April 1984)."Odocoileus hemionus".Mammalian Species(219): 1–9.doi:10.2307/3504024.JSTOR3504024.

- ^Rafinesque, Constantine Samuel (1817). "Extracts from the Journal of Mr. Charles Le Raye, relating to some new Quadrupeds of the Missouri Region, with Notes".The American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review.1(6): 436.hdl:2027/mdp.39015073310313.

- ^abcdefWilson, D. E.;Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005).Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference(3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN978-0-8018-8221-0.OCLC62265494.

- ^abNowak, Ronald M. (7 April 1999).Walker's Mammals of the World.JHU Press.ISBN978-0-8018-5789-8– viaInternet Archive.

- ^abReid, Fiona A. (15 November 2006).Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America(4th ed.).Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.ISBN0-547-34553-4.

- ^abcHeffelfinger, J. (March 2011)."Tails with a Dark Side: The truth about whitetail–mule deer hybrids".Coues Whitetail.Archived fromthe originalon 9 February 2014.Retrieved8 January2014.

- ^abcdeGeist, Valerius (January 1998).Deer of the World: Their Evolution, Behaviour, and Ecology.Stackpole Books.ISBN978-0-8117-0496-0.

- ^abFeldhamer, George A.; Thompson, Bruce C.; Chapman, Joseph A. (19 November 2003).Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation.JHU Press.ISBN978-0-8018-7416-1.

- ^Heffelfinger, J. (11 April 2000)."Status of the name Odocoileus hemionus crooki (Mammalia: Cervidae)"(PDF).Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington.113(1): 319–333.Archived(PDF)from the original on 15 September 2020.

- ^ab"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • inaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • inaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^"Observations • iNaturalist".Retrieved8 June2024.

- ^Petersen, David (1 November 1985)."North American Deer: Mule, Whitetail and Coastal Blacktail Deer".Mother Earth News.Ogden Publications.Archived fromthe originalon 15 March 2012.Retrieved4 January2012.

- ^abMisuraca, Michael (1999)."Odocoileus hemionus mule deer".Animal Diversity Web.University of MichiganMuseum of Zoology.Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2020.

- ^Burnie, David (1 September 2011).Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife.Dorling Kindersley Limited.ISBN978-1-4053-6233-7.

- ^Timm, Robert M.; Slade, Norman A.; Pisani, George R."Mule Deer Odocoileus hemionus (Rafinesque)".Mammals of Kansas.Archivedfrom the original on 1 July 2015.Retrieved8 January2014.

- ^"Sitka Black-tailed Deer Hunting Information".Alaska Department of Fish and Game. 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 23 January 2016.Retrieved8 January2014.

- ^abc"Animal Fact Sheet: Mule Deer".Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum.2008. Archived fromthe originalon 15 September 2020.Retrieved22 May2012.

- ^Anderson, Mike (5 March 2019)."DWR Biologists Use Helicopter Rides, Ultrasound, To Check on Deer Pregnancies".KSL-TV.Cache County, UT:Bonneville International.Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2020.Retrieved13 March2019.

- ^abcMejía Salazar, María Fernanda; Waldner, Cheryl; Stookey, Joseph; Bollinger, Trent K. (23 March 2016)."Infectious Disease and Grouping Patterns in Mule Deer".PLOS One.11(3): e0150830.Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1150830M.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150830.ISSN1932-6203.PMC4805189.PMID27007808.

- ^abcdHeffelfinger, Jim (September 2006).Deer of the Southwest: A Complete Guide to the Natural History, Biology, and Management of Southwestern Mule Deer and White-tailed Deer.Texas A&M University Press.pp. 97–111.ISBN1585445150.

- ^Kufeld, Roland C.; Wallmo, O. C.; Feddema, Charles (July 1973).Foods of the Rocky Mountain Mule Deer(Report).USDA Forest Service.OL14738499M– viaInternet Archive.

- ^abcdeColoradoNatural Resources Conservation Service(March 2000)."Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) Fact Sheet"(PDF).USDA.Archived(PDF)from the original on 15 September 2020.

- ^Anthony, Robert G.; Smith, Norman S. (February 1977). "Ecological Relationships between Mule Deer and White-Tailed Deer in Southeastern Arizona".Ecological Monographs.47(3): 255–277.Bibcode:1977EcoM...47..255A.doi:10.2307/1942517.hdl:10150/287962.JSTOR1942517.

- ^Armstrong, David M. (19 June 2012)."Species Profile: Deer".Colorado Division of Wildlife.Archived fromthe originalon 8 January 2014.Retrieved8 January2014.

- ^Martin, Alexander Campbell; Zim, Herbert Spencer; Nelson, Arnold L. (1961).American Wildlife & Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits: The Use of Trees, Shrubs, Weeds, and Herbs by Birds and Mammals of the United States.Dover Publications.ISBN978-0-486-20793-3– viaInternet Archive.

- ^McCune, Bruce; Grenon, Jill; Mutch, Linda S.; Martin, Erin P. (2007). "Lichens in relation to management issues in the Sierra Nevada national parks".North American Fungi.2:2, 4.doi:10.2509/pnwf.2007.002.003(inactive 19 March 2024).

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2024 (link) - ^abRue, Leonard Lee III (October 1997).The Deer of North America.Lyons Press.pp. 499–502.ISBN1558215778.

- ^Mule Deer: Changing Landscapes, Changing Perspectives: Supplemental Feeding—Just Say No(PDF)(Report). Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies Mule Deer Working Group. pp. 25–26.Archived(PDF)from the original on 29 May 2020 – viaUtah Division of Wildlife Resources.

- ^Kucera, Thomas E. (21 August 1978). "Social Behavior and Breeding System of the Desert Mule Deer".Journal of Mammalogy.59(3): 463–476.doi:10.2307/1380224.ISSN0022-2372.JSTOR1380224.

- ^Bowyer, R. Terry; McCullough, Dale R.; Belovsky, G. E."Causes and consequences of sociality in mule deer"(PDF).Alces.37(2): 371–402.Archived(PDF)from the original on 15 September 2020.

- ^Reiczigel, Jenő; Mejia Salazar, María Fernanda; Bollinger, Trent K.; Rózsa, Lajos (1 December 2015)."Comparing radio-tracking and visual detection methods to quantify group size measures".European Journal of Ecology.1(2): 1–4.doi:10.1515/eje-2015-0011.S2CID52990318.

- ^McCusker, S.; Shipley, L. A.; Tollefson, T. N.; Griffin, M.; Koutsos, E. A. (3 July 2011). "Effects of starch and fibre in pelleted diets on nutritional status of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) fawns".Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition.95(4): 489–498.doi:10.1111/j.1439-0396.2010.01076.x.PMID21091543.

- ^deCalesta, David S.; Nagy, Julius G.; Bailey, James A. (October 1975). "Starving and Refeeding Mule Deer".The Journal of Wildlife Management.39(4): 663.doi:10.2307/3800224.JSTOR3800224.

- ^Wallmo, O. C.; Carpenter, L. H.; Regelin, W. L.; Gill, R. B.; Baker, D. L. (March 1977). "Evaluation of Deer Habitat on a Nutritional Basis".Journal of Range Management.30(2): 122.doi:10.2307/3897753.hdl:10150/646885.JSTOR3897753.

- ^Bergman, Eric J.; Doherty, Paul F.; Bishop, Chad J.; Wolfe, Lisa L.; Banulis, Bradley A.; Kaltenboeck, Bernhard (3 September 2014)."Herbivore Body Condition Response in Altered Environments: Mule Deer and Habitat Management".PLOS One.9(9): e106374.Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j6374B.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106374.PMC4153590.PMID25184410.

- ^ab"Red Desert to Hoback Migration Assessment | Wyoming Migration Initiative".migrationinitiative.org.Archived fromthe originalon 28 February 2021.Retrieved25 February2021.

- ^Aug. 20, Emily Benson; Now, 2018 From the print edition Like Tweet Email Print Subscribe Donate (20 August 2018)."The long, strange trip of Deer 255".hcn.org.Retrieved25 February2021.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^"Colorado Parks & Wildlife - Species Data - Mule Deer Migration Corridors - Colorado GeoLibrary".geo.colorado.edu.Retrieved25 February2021.

- ^"New big game studies in Montana aimed at declining numbers, disease".goHUNT.Archived fromthe originalon 22 October 2020.Retrieved25 February2021.

- ^"Mule Deer Initiative".Idaho Fish and Game.19 September 2016.Retrieved25 February2021.

- ^Lewis, Gary (23 February 2017)."Central Oregon mule deer migrations in crisis".The Bulletin.Retrieved25 February2021.

- ^"UNDERSTANDING MULE DEER MIGRATIONFact Sheet #12"(PDF).Mule Deer Working Group: Fact Sheet.

- ^ab"New study: Migrating mule deer don't need directions".EurekAlert!.Retrieved15 March2021.

- ^"Impacts of climate change on migrating mule deer".ScienceDaily.Retrieved6 April2021.

- ^Aikens, Ellen O.; Monteith, Kevin L.; Merkle, Jerod A.; Dwinnell, Samantha P. H.; Fralick, Gary L.; Kauffman, Matthew J. (August 2020)."Drought reshuffles plant phenology and reduces the foraging benefit of green-wave surfing for a migratory ungulate".Global Change Biology.26(8): 4215–4225.Bibcode:2020GCBio..26.4215A.doi:10.1111/gcb.15169.ISSN1354-1013.PMID32524724.S2CID219586821.

- ^abSawyer, Hall; Kauffman, Matthew J.; Nielson, Ryan M. (September 2009)."Influence of Well Pad Activity on Winter Habitat Selection Patterns of Mule Deer".Journal of Wildlife Management.73(7): 1052–1061.Bibcode:2009JWMan..73.1052S.doi:10.2193/2008-478.ISSN0022-541X.S2CID26214504.

- ^Coe, Priscilla K.; Nielson, Ryan M.; Jackson, Dewaine H.; Cupples, Jacqueline B.; Seidel, Nigel E.; Johnson, Bruce K.; Gregory, Sara C.; Bjornstrom, Greg A.; Larkins, Autumn N.; Speten, David A. (June 2015)."Identifying migration corridors of mule deer threatened by highway development: Mule Deer Migration and Highways".Wildlife Society Bulletin.39(2): 256–267.doi:10.1002/wsb.544.

- ^"Abandoned Fencing Is Detrimental to Mule Deer and Other Wildlife".John In The Wild.9 May 2019.Retrieved6 April2021.

- ^ab"New Study Finds That Expanding Development Is Associated With Declining Deer Recruitment Across Western Colorado".newsroom.wcs.org.Retrieved6 April2021.

- ^Sawyer, Hall; Kauffman, Matthew J.; Middleton, Arthur D.; Morrison, Thomas A.; Nielson, Ryan M.; Wyckoff, Teal B. (5 December 2012)."A framework for understanding semi-permeable barrier effects on migratory ungulates".Journal of Applied Ecology.50(1): 68–78.doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12013.ISSN0021-8901.

- ^"New study reveals how fences hinder migratory wildlife in Western US".ScienceDaily.Retrieved6 April2021.

- ^July 17; Denchak, 2017 Melissa."How You Can Stop Global Warming".NRDC.Retrieved6 April2021.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^"Protecting big-game migration corridors".NFWF.Retrieved6 April2021.

- ^abSiemers, Jeremy L.; Wilson, Kenneth R.; Baruch-Mordo, Sharon (May 2015)."MONITORING WILDLIFE-VEHICLE COLLISIONS: ANALYSIS AND COST- BENEFIT OF ESCAPE RAMPS FOR DEER AND ELK ON U.S. HIGHWAY 550".Colorado Department of Transportation: Applied Research and Innovation Branch.

- ^staff, the Star-Tribune (8 October 2013)."Wyoming wildlife crossings labeled success".Casper Star-Tribune Online.Retrieved7 April2021.

- ^"Study quantifies natural gas development impacts on mule deer".SOURCE.12 August 2015.Retrieved7 April2021.

- ^Fraser, Devaughn L.; Ironside, Kirsten; Wayne, Robert K.; Boydston, Erin E. (May 2019)."Connectivity of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) populations in a highly fragmented urban landscape".Landscape Ecology.34(5): 1097–1115.Bibcode:2019LaEco..34.1097F.doi:10.1007/s10980-019-00824-9.ISSN0921-2973.S2CID145022000.

- ^ab"URBAN MULE DEER ISSUES Fact Sheet #9"(PDF).Mule Deer Working Group Fact Sheet.July 2014.

- ^"UNDERSTANDING MULE DEER MIGRATION Fact Sheet #12"(PDF).Mule Deer Working Group. July 2014.

- ^Harkins, Paighten (29 March 2022)."Utah mule deer is 1st in U.S. to test positive for COVID-19".The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived fromthe originalon 29 March 2022.Retrieved29 March2022.

- ^Prettyman, Brett (19 October 2008)."Hunting: Whitetail deer influx brings mixed reaction".The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived fromthe originalon 29 March 2022.

- ^Jacobs, Andrew (2 November 2021)."Widespread Coronavirus Infection Found in Iowa Deer, New Study Says".The New York Times.Archived fromthe originalon 2 November 2021.Retrieved5 November2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Woodman, Neal (2015). "Who invented the mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus)? On the authorship of the fraudulent 1812 journal of Charles Le Raye ".Archives of Natural History.42(1): 39–50.doi:10.3366/anh.2015.0277.