Musar literature

| Part ofa serieson |

| JewsandJudaism |

|---|

Musar literatureisdidacticJewishethicalliteraturewhich describes virtues and vices and the path towards character improvement. This literature gives the name to theMusar movement,in 19th century Lithuania, but this article considers such literature more broadly.

Definition[edit]

Musar literature is often described as "ethical literature." ProfessorGeoffrey Claussendescribes it as "Jewish literature that discusses virtue and character."[1]ProfessorsIsaiah TishbyandJoseph Danhave described it as "prose literature that presents to a wide public views, ideas, and ways of life in order to shape the everyday behavior, thought, and beliefs of this public."[2]Musar literature traditionally depicts the nature of moral and spiritual perfection in a methodical way. It is "divided according to the component parts of the ideal righteous way of life; the material is treated methodically – analyzing, explaining, and demonstrating how to achieve each moral virtue (usually treated in a separate chapter or section) in the author's ethical system."[3]

Musar literature can be distinguished from other forms ofJewish ethicalliterature such asaggadicnarrative andhalakhicliterature.

Early Musar literature[edit]

In Judaism,ethical monotheismoriginated, and along with it came the highly didacticethics in the Torah and Tanach.

Mishleiis commonly regarded as a musar classic in its own right and is arguably the first true "musar sefer." In fact, the Hebrew word musar (מוסר, discipline) being the title of this genre stems from the word's extensive use in the book of Mishlei.

An example from theTanakhis the earliest known text of the positive form of the famous "Golden Rule":[4]

You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against your kinsfolk. Love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.

Hillel the Elder(c. 110 BCE – 10 CE)[6]used this verse as a most important message of theTorahfor his teachings. Once, he was challenged by ager toshavwho asked to be converted under the condition that the Torah be explained to him while he stood on one foot. Hillel accepted him as a candidate forconversion to Judaismbut, drawing onLeviticus 19:18,briefed the man:

What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow: this is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation; go and learn.

Pirkei Avotis a compilation of theethicalteachings and maxims of the Rabbis of theMishnaicperiod. It is part ofdidacticJewishethical Musar literature. Because of its contents, it is also calledEthics of the Fathers.The teachings of Pirkei Avot appear in the MishnaictractateofAvot,the second-to-last tractate in the order ofNezikinin the Mishnah. Pirkei Avot is unique in that it is the only tractate of the Mishnah dealing solely with ethical and moral principles; there is little or nohalachafound in Pirkei Avot.

Medieval Musar literature[edit]

Medieval works of Musar literature were composed by a range of rabbis and others, including rationalist philosophers and adherents of Kabbalistic mysticism.Joseph Danhas argued that medieval Musar literature reflects four different approaches: thephilosophical approach;the standardrabbinic approaches;the approach ofChassidei Ashkenaz;and theKabbalisticapproach.[3]

Philosophical Musar literature[edit]

Philosophicalworks of Musar include:

- Chovot ha-LevavotbyBahya ibn Paquda

- Hilchot DeotinSefer ha-MadahofMishneh TorahbyMaimonides

- Sefer Hayashar(the ethical work, not to be confused with the many other unrelated works of the same name), published anonymously

- Shemona Perakim( "The Eight Chapters" ):, the introduction toPirkei AvotinMaimonides' commentary to theMishnah.

Standard Rabbinic Musar literature[edit]

RabbinicMusar literature came as a reaction to philosophical literature, and tried to show that the Torah and standardrabbinic literaturetaught about the nature of virtue and vice without recourse to Aristotelian or other philosophical concepts. Classic works of this sort include

- Ma'alot ha-Middotby Rabbi Yehiel ben Yekutiel Anav of Rome

- Shaarei Teshuvah(The Gates of Repentance) by RabbiYonah Gerondi

- Menorat ha-Ma'orby Israel Al-Nakawa b. Joseph of Toledo

- Menorat ha-Ma'orbyIsaac Aboab

- Orchot Tzaddikim(The Ways of the Righteous), by an anonymous author

- Meneket RivkahbyRebecca bat Meir Tiktiner

Similar works were produced by rabbis who wereKabbalistsbut whose Musar writings did not bear a kabbalistic character:Nahmanides'Sha'ar ha-Gemul,which focuses on various categories of just and wicked people and their punishments in the world to come; and RabbiBahya ben Asher'sKad ha-Kemah.

Medieval Ashkenazi-Hasidic Musar literature[edit]

Chassidei Ashkenaz(literally "the Pious of Germany" ) was a Jewish movement in the 12th century and 13th century founded by RabbiJudah the Pious(Rabbi Yehuda HeChassid) ofRegensburg,Germany, which was concerned with promoting Jewish piety and morality. The most famous work of Musar literature produced by this school wasThe Book of the Pious(Sefer Hasidim).[3]

Medieval Kabbalistic Musar literature[edit]

ExplicitlyKabbalisticmystical works of Musar literature includeTomer Devorah(The Palm Tree of Deborah) byMoses ben Jacob Cordovero,Reshit ChochmahbyEliyahu de Vidas,andKav ha-YasharbyTzvi Hirsch Kaidanover.

Modern Musar literature[edit]

Literature in the genre of Musar literature continued to be written by modern Jews from a variety of backgrounds.

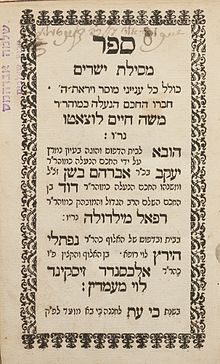

Mesillat Yesharim[edit]

Mesillat Yesharimis a Musar text published in Amsterdam byMoshe Chaim Luzzattoin the 18th century. Mesillat Yesharim is perhaps the most important work of Musar literature of the post-medieval period. TheVilna Gaoncommented that he could not find a superfluous word in the first seven chapters of the work, and stated that he would have traveled to meet the author and learn from his ways if he'd still been alive.

Ottoman Musar literature[edit]

According toJulia Phillips Cohen,summarizing the work of Matthias B. Lehmann on Musar literature inOttomanSephardicsociety:

Beginning in the eighteenth century, a number of Ottoman rabbis had undertaken the task of fighting the ignorance they believed was plaguing their communities by producing works of Jewish ethics (musar) inJudeo-Spanish(also known as Ladino). This development was inspired in part by a particular strain withinJewish mysticism(LurianicKabbalah) which suggested that every Jew would necessarily play a role in the mending of the world required for redemption. The spread of ignorance among their coreligionists thus threatened to undo the proper order of things. It was with this in mind that these Ottoman rabbis--all capable of publishing in the more highly esteemedHebrewlanguage of their religious tradition--chose to write in their vernacular instead. While they democratized rabbinic knowledge by translating it for the masses, these "vernacular rabbis" (to use Matthias Lehmann's term) also attempted to instill in their audiences the sense that their texts required the mediation of individuals with religious training. Thus, they explained that common people should gather together to read their books inmeldados,or study sessions, always with the guidance of someone trained in the study ofJewish law.[7]

Among the most popular works of Musar literature produced in Ottoman society was Elijah ha-Kohen'sShevet Musar,first published inLadinoin 1748.[8]Pele Yoetzby RabbiEliezer Papo(1785–1826) was another exemplary work of this genre.[9]

Haskalah Musar literature[edit]

In Europe, significant contributions to Musar literature were made by leaders of theHaskalah.[10][11]Naphtali Hirz Wesselywrote a Musar text titledSefer Ha-Middot(Book of Virtues) in approximately 1786.Menachem Mendel LefinofSatanovwrote a text titledCheshbon Ha-Nefesh(Moral Accounting) in 1809, based in part on the ethical program described in the autobiography ofBenjamin Franklin.[12]

Hasidic Musar literature[edit]

One form of literature in theHasidicmovement were tracts collecting and instructing mystical-ethical practices. These includeTzavaat HaRivash( "Testament of RabbiYisroel Baal Shem") and Tzetl Koton byElimelech of Lizhensk,a seventeen-point program on how to be a good Jew. RabbiNachman of Breslov's Sefer ha-Middot is aHasidicclassic of Musar literature.[1]

Mitnagdic and Yeshivish Musar literature[edit]

The "Musar letter" of theVilna Gaon,an ethical will by anopponentof the Hasidic movement, is regarded by some as a classic of Musar literature.[13]Many of the writings ofYisrael Meir Kaganhave also been described as Musar literature.[14]

Literature by the Musar movement[edit]

The modernMusar movement,beginning in the 19th century, encouraged the organized study of medieval Musar literature to an unprecedented degree, while also producing its own Musar literature. Significant Musar writings were produced by leaders of the movement such as RabbisIsrael Salanter,Simcha Zissel Ziv,Yosef Yozel Horwitz,andEliyahu Dessler.[1]The movement established musar learning as a regular part of the curriculum in theLithuanianYeshivaworld, acting as a bulwark against contemporary forces of secularism.

Musar literature by Reform rabbis[edit]

Musar literature has been composed by Reform rabbis includingRuth Abusch-Magder,noted for her writing on humility, andKaryn Kedar,noted for her writing on forgiveness.[1]

Musar literature by Conservative rabbis[edit]

Musar literature has been composed by Conservative rabbis includingAmy Eilberg(noted for her writing on curiosity and courage) andDanya Ruttenberg(noted for her writing on curiosity).[1]

Musar literature by Reconstructionist rabbis[edit]

Musar literature has been composed byReconstructionistrabbis includingSusan Schnur(noted for her writing on forgiveness),Sandra Lawson(noted for her writing on curiosity),Rebecca Alpert(noted for her writing on humility), andMordecai Kaplan(noted for his writing on humility).[1]Schnur's writing show how gender matters in discussions of forgiveness as a virtue.[1]

References[edit]

- ^abcdefgClaussen, Geoffrey D. (2022).Modern Musar: Contested Virtues in Jewish Thought.University of Nebraska Press.ISBN978-0-8276-1888-6.

- ^Isaiah Tishby and Joseph Dan,Mivhar sifrut ha-mussar(Jerusalem, 1970), 12.

- ^abcJoseph Dan, "Ethical Literature"Encyclopaedia Judaica,ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 6.

- ^Gunther Plaut,The Torah — A Modern Commentary;Union of American Hebrew Congregations, New York 1981; pp.892.

- ^New JPS Hebrew/English Tanakh

- ^Jewish Encyclopedia: Hillel:"His activity of forty years is perhaps historical; and since it began, according to a trustworthy tradition (Shab. 15a), one hundred years before the destruction of Jerusalem, it must have covered the period 30 B.C.E. -10 C.E."

- ^Julia Phillips Cohen,http:// h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=26171

- ^Matthias B. Lehmann, Ladino rabbinic literature and Ottoman Sephardic culture, 6, 9

- ^"Judaism 101 - Rabbi Eliezer Papo: Pele Yoetz - Duties of the Heart - A Glossary of Basic Jewish Terms and Concepts - OU.ORG".Archived fromthe originalon 2012-09-05.Retrieved2011-01-06.

- ^Shmuel Feiner, David Jan Sorkin,New perspectives on the Haskalah,page 49

- ^David Sorkin, The transformation of German Jewry, 1780-1840, page 46

- ^Nancy Sinkoff,Out of the Shtetl: Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands(Brown Judaic Studies, 2020), pp. 50-167; Shai Afsai, "Benjamin Franklin’s Influence onMussarThought and Practice: a Chronicle of Misapprehension,"Review of Rabbinic Judaism22, 2 (2019): 228-276; Shai Afsai, "The Sage, the Prince & the Rabbi,"Philalethes64, 3 (2011): 101-109,128.

- ^"The Mussar Way"Archived2012-07-20 at theWayback Machine,Mussar Institute website, accessed 11-22-2010

- ^Rabbi Dov Katz (1996).Musar movement: Its history, leading personalities and doctrines(new ed.). Feldheim Publishers.