Myrtus

| Myrtus Myrtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Myrtus communis | |

| |

| Myrtle(M. communis)[3] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Subfamily: | Myrtoideae |

| Tribe: | Myrteae |

| Genus: | Myrtus L. |

| Type species | |

| Myrtus communis | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

|

MyrthusScop. | |

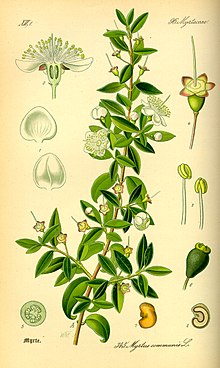

Myrtus(commonly calledmyrtle) is agenusofflowering plantsin the familyMyrtaceae.It was first described by Swedish botanistLinnaeusin 1753.[2]

Over 600 names have been proposed in the genus, but nearly all have either been moved to other genera or been regarded as synonyms. The genusMyrtushas threespeciesrecognised today:[5]

- Myrtus communis– Common myrtle; native to the Mediterranean region in southernEurope

- Myrtus nivellei– Saharan myrtle; native toNorth Africa

- Myrtus phyllireaefolia

Description[edit]

Common myrtle[edit]

Myrtus communis,the "common myrtle", is native across theMediterranean region,Macaronesia,western Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. It is also cultivated.

The plant is anevergreenshrubor smalltree,growing to 5 metres (16 ft) tall. Theleafis entire, 3–5 cm long, with a fragrantessential oil.

The star-likeflowerhas five petals and sepals, and numerousstamens.Petals usually are white. The flower is pollinated byinsects.

The fruit is a roundberrycontaining severalseeds,most commonly blue-black in colour. A variety with yellow-amber berries is also present. The seeds are dispersed bybirdsthat eat the berries.

Saharan myrtle[edit]

Myrtus nivellei,theSaharan myrtle,(Tuareg language:tefeltest), isendemicto the mountains of the centralSahara Desert.[6]It is found in a restricted range in theTassili n'AjjerMountains in southernAlgeria,and theTibesti Mountainsin northernChad.

It occurs in small areas of sparse relict woodland at montane elevations above the central Saharan desert plains.[6]

It is a traditionalmedicinal plantfor theTuareg people.[6]

Fossil record[edit]

Two hundred and fiftyfossilseedsof †Myrtus palaeocommunishave been described frommiddle Miocenestrataof the Fasterholt area nearSilkeborgin CentralJutland,Denmark.[7]

Uses[edit]

Gardening[edit]

Myrtus communisis widely cultivated as anornamental plantfor use as ashrubingardensandparks.It is often used as ahedgeplant, with its small leaves shearing cleanly.

When trimmed less frequently, it has numerous flowers in late summer. It requires a long hot summer to produce its flowers, and protection from winter frosts.

The species and thesubspeciesM. communissubsp.tarentinahave gained theRoyal Horticultural Society'sAward of Garden Merit.[8][9]

Culinary[edit]

Myrtus communisis used in the islands ofSardiniaandCorsicato produce an aromatic liqueur calledMirtobymaceratingit in alcohol.Mirtois one of the most typical drinks of Sardinia and comes in two varieties:mirto rosso(red) produced by macerating the berries, andmirto bianco(white) produced from the less common yellow berries and sometimes the leaves.[10]

Many Mediterranean pork dishes include myrtle berries, and roasted piglet is often stuffed with myrtle sprigs in the belly cavity, to impart an aromatic flavour to the meat.

The berries, whole or ground, have been used as a pepper substitute.[11]They contribute to the distinctive flavor of some versions of ItalianMortadellasausage and the related AmericanBologna sausage.

In Calabria, a myrtle branch is threaded through dried figs and then baked. The figs acquire a pleasant taste from the essential oils of the herb. They are then enjoyed through the winter months.

Medicinal[edit]

Myrtle, along withwillow treebark, occupies a minor place in the writings ofHippocrates,Pliny,Dioscorides,Galen, and the Arabian writers.[12]Celsus,for instance, suggested that 'soda in vinegar, or ladanum in myrtle oil and wine' could be used to treat various ailments of the scalp.[13]It is possible that Myrtle's effect was due to high levels ofsalicylic acid.

In several countries, particularly in Europe and China, there has been a tradition for prescribing this substance forsinus infections.A systematic review of herbal medicines used for the treatment ofrhinosinusitisconcluded that the evidence that any herbal medicines are beneficial in the treatment of rhinosinusitis is limited, and that forMyrtusthere is insufficient data to verify the significance of clinical results.[14] In traditional Persian medicine myrtus communis, specially the leaves, are used to stop bleeding. In a research the aqueous extract of the leaves showed hemostatic activity in the rat tail-bleeding model.[15]

In myth and ritual[edit]

Classical[edit]

InGreek mythologyand ritual the myrtle was sacred to the goddessesAphrodite[16]and alsoDemeter:Artemidorusasserts that in interpreting dreams "a myrtle garland signifies the same as an olive garland, except that it is especially auspicious for farmers because of Demeter and for women because of Aphrodite. For the plant is sacred to both goddesses."[17]Pausaniasexplains that one of the Graces in the sanctuary atElisholds a myrtle branch because "the rose and the myrtle are sacred to Aphrodite and connected with the story ofAdonis,while the Graces are of all deities the nearest related to Aphrodite. "Myrtle is the garland ofIacchus,according toAristophanes,[18]and of the victors at theThebanIolaea,held in honour of the Theban heroIolaus.[19]

Two myths are connected to the myrtle; in the first,Myrsinewas a chaste girl beloved byAthenawho outdid all the other athletes, so they murdered her in retaliation. Athena turned her into a myrtle, which became sacred to her.[20]In the second,Myrinawas a dedicated priestess of Aphrodite who was either abducted to be married or willingly wished to entered marriage in spite of her vows. In any case, Aphrodite turned her into myrtle, and gave it fragrant smell, as her favourite and sacred plant.[21][22]

In Rome, Virgil explains that "the poplar is most dear toAlcides,the vine toBacchus,the myrtle to lovelyVenus,and his ownlaureltoPhoebus."[23]At theVeneralia,women bathed wearing crowns woven of myrtle branches, and myrtle was used in wedding rituals. In theAeneid,myrtle marks the grave of the murderedPolydorusinThrace.Aeneas' attempts to uproot the shrub cause the ground to bleed, and the voice of the dead Polydorus warns him to leave. The spears which impaled Polydorus have been magically transformed into the myrtle which marks his grave.[24]

Afghan Tradition[edit]

InAfghanandPersian(Iranian) traditions, the myrtle leaves are used to avoid evil eyes. The leaves (preferably dry ones) are set on fire, fumigated and smoke is acquired like the same what is believed aboutPeganum harmala.InAfghanistanit's named "ماڼو" (māṇo).[25]

Jewish[edit]

InJewish liturgy,the myrtle is one of thefour species(sacred plants) ofSukkot,representing the different types of personality making up the community. The myrtle having fragrance but not pleasant taste, represents those who have good deeds to their credit despite not having knowledge fromTorahstudy. The three branches are lashed or braided together by the worshipers apalmleaf, awillowbough, and a myrtle branch. Theetrogorcitronis the fruit held in the other hand as part of thelulavwave ritual.

Myrtle branches were sometimes given the bridegroom as he entered the nuptial chamber after a wedding (Tos. Sotah 15:8; Ketubot 17a). Myrtles are both the symbol and scent of theGarden of Eden(BhM II: 52; Sefer ha-Hezyonot 17). TheHekhalot texttheMerkavah Rabbahrequires one to suck on a myrtle leaves as an element of atheurgic ritual.Kabbalists link myrtle to thesefiraofTiferetand use sprigs in theirShabbat(especiallyHavdalah) rites to draw down its harmonizing power as the week is initiated (Shab. 33a; Zohar Chadash, SoS, 64d; Sha’ar ha-Kavvanot, 2, pp. 73–76).[26]

Myrtle leaves were added to the water in the last (seventh) rinsing of the head in the traditionalSephardictaharamanual (teaching the ritual for washing the dead).[27]Myrtles are often used to recite a blessing over a fragrant plant during theHavdalahceremony, as well as beforekiddushis some Sefardic andHasidictraditions.

Mandaean[edit]

In theMandaean religion,myrtle wreaths (klila) are used by priests in important religious rituals and ceremonies, such asbaptismand death masses (masiqta).[28]Myrtle wreaths also form part of thedarfash,the official symbol ofMandaeismconsisting of an olive wooden cross covered with a white silk cloth.

Contemporary[edit]

In neo-pagan and wicca rituals, myrtle, though not indigenous beyond the Mediterranean Basin, is now commonly associated with and sacred toBeltane(May Day).

Myrtle in a wedding bouquet is a general European custom.[29]

A sprig of myrtle fromQueen Victoria's wedding bouquet was planted as a slip,[30]and sprigs from it have continually been included in royal wedding bouquets.

Garden history[edit]

Rome[edit]

Because of its elegance of habit, appealing odour, and amenity to clipping by thetopiarius,as much as for sacred associations, the myrtle was an indispensable feature ofRoman gardens.As a reminder of home, it will have been introduced wherever Roman elites were settled, even in areas of theMediterranean Basinwhere it was not already endemic: "the Romans... must surely have attempted to establish a shrub so closely associated with their mythology and tradition," observesAlice Coats.[31]InGaulandBritanniait will not have proved hardy.

England[edit]

In England it was reintroduced in the 16th century, traditionally with the return from Spain in 1585 ofSir Walter Raleigh,who also brought with him the firstorange treesseen in England.[citation needed]Myrtus communiswill have needed similar protection from winter cold and wet. Alice Coats[32]notes an earlier testimony: in 1562,Queen Elizabeth I's great ministerLord Burghleywrote to Mr Windebank in Paris to ask him for a lemon, a pomegranate and a myrtle, with instructions for their culture—which suggests that the myrtle, like the others, was not yet familiar.

By 1597,John Gerardlists six varieties being grown in southern England,[33]and by 1640John Parkinsonnoted a double-flowering one. Alice Coats suggests that this was the very same double that the diarist and gardenerJohn Evelynnoted "was first discovered by the incomparableNicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc,which a mule had cropt from a wild shrub. "

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, myrtles in cases, pots and tubs were brought out to summer in the garden and wintered with other tender greens in anorangery.Fairchild,The City Gardener(1722) notes their temporary use, rented from a nurseryman annually to fill an empty fireplace in the warm months.

With the influx to England of more dramatic tender plants and shrubs from Japan or Peru in the 19th century, it was more difficult to find room for the common myrtle of borderline hardiness.

Related plants[edit]

Many other related plants native toSouth America,New Zealandand elsewhere, previously classified in a wider interpretation of the genusMyrtus,are now species within other genera, including:Eugenia,Lophomyrtus,Luma,Rhodomyrtus,Syzygium,Ugni,and at least a dozen other genera.

The name "myrtle" is also used in common names (vernacular names) of unrelated plants in several other genera, such as: "Crepe myrtle" (Lagerstroemiaspecies and hybrids,Lythraceae); "Wax myrtle" (Morellaspecies,Myricaceae); and "Creeping myrtle" (Vincaspecies,Apocynaceae).

References[edit]

- ^lectotype designated by A.P. de Candolle, Note Myrt. 7 (1826)

- ^abTropicos,MyrtusL.

- ^1885 illustration from Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz 1885, Gera, Germany

- ^Kew World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

- ^The Plant List,retrieved13 August2016

- ^abcUicnmed.org:Myrtus nivellei- Batt & Trab. - Myrtaceae.accessed 1.10.2014.

- ^Angiosperm Fruits and Seeds from the Middle Miocene of Jutland (Denmark) byElse Marie Friis,The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters 24:3, 1985

- ^"RHS Plant Selector -Myrtus communis".Archived fromthe originalon 10 January 2014.Retrieved25 May2013.

- ^"RHS Plant Selector -Myrtus communissubsp.tarentina".Retrieved25 May2013.

- ^it:Liquore di mirto

- ^"Myrtle".The Epicentre.Retrieved16 July2014.

- ^Pharmacographia Indica (1891 edition), London

- ^Celsus, Aulus."De Medicina".Retrieved10 January2022.

- ^Guo, R; Canter, PH; Ernst, E (2006). "Herbal medicines for the treatment of rhinosinusitis: A systematic review".Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.135(4): 496–506.doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2006.06.1254.PMID17011407.S2CID42625009.

- ^Ebrahimi F, Mahmoudi J, Torbati M, Karimi P, Valizadeh H. Hemostatic activity of aqueous extract of Myrtus communis L. leaf in topical formulation: In vivo and in vitro evaluations. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020 Mar 1;249:112398. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112398. Epub 2019 Nov 23. PMID 31770566.

- ^V. Pirenne-Delforge, "Épithètes cultuelles et interpretation philosophique: à propos d’Aphrodite Ourania et Pandémos à Athènes."AntCl57(1980::142-57) p. 413.

- ^Artemidorus,Oneirocritica,I.77. (translation byHugh G. Evelyn-White).

- ^Aristophanes,The Frogs,the Iacchus chorus, 330ff.

- ^Pindar,Isthmian OdeIV.

- ^Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth; Salazar, Christine F.; Orton, David E. (2002).Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World.Vol. IX.Brill Publications.p. 423.ISBN978-90-04-12272-7.

- ^Hünemörder, Christian (Hamburg),“Myrtle”,inBrill's New Pauly.Antiquity volumes edited by: Hubert Cancik and, Helmuth Schneider, English Edition by: Christine F. Salazar, Classical Tradition volumes edited by: Manfred Landfester, English Edition by: Francis G. Gentry. Consulted online on 09 January 2023.

- ^Pepin, Ronald E. (2008).The Vatican Mythographers.New York City:Fordham University Press.p.117.ISBN978-0-8232-2892-8.

- ^Virgil,EclogueVII.61-63.

- ^Aeneid III, 19-68,accessed 13 March 2014

- ^[1]ماڼو (صفیه حلیم وېبپاڼه)

- ^List of plants in the Bible

- ^Service for Preparing the Dead for Burial, as Used in the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation, Shearith Israel, NY City, Published by the Society "Hebra Hased ba'Amet", New York, 1913, available athttp:// Jewish-Funerals.org

- ^Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002).The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people.New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-515385-5.OCLC65198443.

- ^Marcel De Cleene, Marie Claire Lejeune, eds.Compendium of symbolic and ritual plants in EuropeVolume 1, 2003:444.

- ^"in a churchyard at Cowes, on the Isle of Wight" according to Vivian A. Rich,Cursing the Basil: And Other Folklore of the Garden1998:18.

- ^Alice M. Coats,Garden Shrubs and Their Histories(1964) 1992,s.v."Myrtus".

- ^Coats (1964) 1992.

- ^Gerard,The Herball,1597.

External links[edit]

- Myrtle (Myrtus communisL.),from Gernot Katzer's Spice Pages

- myrtus-communis.de(German)

- Myrtus in Flora Europaea