Nanbantrade

| Part ofa serieson the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

Nanbantrade(Nam Man mậu dịch,Nanban bōeki,"Southern barbarian trade" )or theNanbantrade period(Nam Man mậu dịch thời đại,Nanban bōeki jidai,"Southern barbarian trade period" )was a period in thehistory of Japanfrom the arrival ofEuropeansin 1543 to the firstSakokuSeclusion Edicts ofisolationismin 1614.[note 1]Nanban( Nam Manlit. 'Southern barbarian') is a Japanese word which had been used to designate people fromSouthern China,theRyukyu Islands,theIndian Ocean,andSoutheast Asiacenturies prior to the arrival of the first Europeans. For instance, according to theNihon Kiryaku( Nhật Bản kỷ lược ),Dazaifu,the administrative center ofKyūshū,reported that the Nanban (southern barbarian) pirates, who were identified asAmamiislanders by theShōyūki(982–1032 for the extant portion), pillaged a wide area of Kyūshū in 997. In response, Dazaifu orderedKikaijima( quý giá đảo ) to arrest the Nanban.[1]

TheNanbantrade as a form of European contact began withPortugueseexplorers, missionaries, and merchantsin theSengoku periodand established long-distance overseastrade routeswith Japan. The resulting technological andcultural exchangeincluded the introduction ofmatchlockfirearms,cannons,galleon-style shipbuilding,Christianityto Japan, among other cultural aspects. TheNanbantrade declined in the earlyEdo periodwith the rise of theTokugawa Shogunatewhich feared the influence of Christianity in Japan, particularly theRoman Catholicismof the Portuguese. The Tokugawa issued a series ofSakokupolicies that increasingly isolated Japan from the outside world and limited European trade toDutchtraders on the island ofDejima.

First contacts

[edit]

Japanese accounts of Europeans

[edit]

Following contact with thePortugueseonTanegashimain 1543, the Japanese were at first rather wary of the newly arrived foreigners. Theculture shockwas quite strong, especially because Europeans were not able to understand theJapanese writing systemnor accustomed to using chopsticks.

They eat with their fingers instead of with chopsticks such as we use. They show their feelings without any self-control. They cannot understand the meaning of written characters. (from Boxer,Christian Century).

European accounts of Japan

[edit]The island ofJampon,according to what all the Chinese say, is larger than that of theLéquios,and the king is more powerful and greater and is not given to trading, nor are his subjects. He is a heathen king, a vassal of the king of China. They do not often trade in China because it is far off and they have nojunks,nor are they seafaring men.[3]

The first comprehensive and systematic report of a European about Japan is theTratado em que se contêm muito sucinta e abreviadamente algumas contradições e diferenças de costumes entre a gente de Europa e esta província de JapãoofLuís Fróis,in which he described Japanese life concerning the roles and duties of men and women, children, Japanese food, weapons, medicine, medical treatment, diseases, books, houses, gardens, horses, ships and cultural aspects of Japanese life like dances and music.[4]Several decades later, whenHasekura Tsunenagabecame the first Japanese official arriving in Europe, his presence, habits and cultural mannerisms gave rise to many picturesque descriptions circulating among the public:

- "They never touch food with their fingers, but instead usetwo small sticksthat they hold with three fingers. "

- "They blow their noses insoft silky papersthe size of a hand, which they never use twice, so that they throw them on the ground after usage, and they were delighted to see our people around them precipitate themselves to pick them up. "

- "TheirScimitar-likeswordsand daggers cut so well that they can cut a soft paper just by putting it on the edge and by blowing on it. "(" Relations of Mme de St Tropez ", October 1615, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, Carpentras).[5]

Renaissance Europeans were quite fond of Japan's immense richness in precious metals, mainly owing toMarco Polo's accounts of gilded temples and palaces, but also to the relative abundance of surface ores characteristic of a volcanic country, before large-scale deep-mining became possible in Industrial times. Japan was to become a major exporter ofcopperandsilverduring the period. At its peak, 1/3 of the world's silver came from Japan.[6]

Japan was also noted for its comparable or even exceptional levels of population and urbanization relative to the nations of the West (seeList of countries by population in 1600), and some Europeans became quite fascinated with Japan, withAlessandro Valignanoeven writing that the Japanese "excel not only all the other Oriental peoples, they surpass the Europeans as well".[7]

Early European visitors noted the quality of Japanese craftsmanship and metalsmithing. The later sources, most notably those written after the end ofJapan's isolation period,also report Japanese blades and swords in general as good quality weapons with a notable artistic value.[8][9]

Portuguese trade in the 16th century

[edit]

Ever since 1514 that the Portuguese had traded withChinafromMalacca,and the year after the first Portuguese landfall in Japan, trade commenced between Malacca, China, and Japan. The Chinese Emperor had decreed an embargo against Japan as a result of piraticalwokouraids against China – consequently, Chinese goods were in scarce supply in Japan and so, the Portuguese found a lucrative opportunity to act as middlemen between the two realms.[10]

Trade with Japan was initially open to any, but in 1550, the Portuguese Crown monopolized the rights to trade with Japan.[10]Henceforth, once a year afidalgowas awarded the rights for a single trade venture to Japan with considerable privileges, such as the title ofcaptain-major of the voyage to Japan,with authority over any Portuguese subjects in China or Japan while he was in port, and the right to sell his post, should he lack the necessary funds to undertake the enterprise. He could charter a royal vessel or purchase his own, at about 40,000xerafins.[11]His ship would set sail from Goa, called at Malacca and China before proceeding to Japan and back.

In 1554, captain-major Leonel de Sousanegotiated with Chinese authorities the re-legalization of Portuguese trade in China,which was followed by the foundation ofMacauin 1557 to support this trade.[12]

The state of civil-war in Japan was also highly beneficial to the Portuguese, as each competing lord sought to attract trade to their domains by offering better conditions.[13]In 1571, the fishing village of Nagasaki became the definitive anchorage of the Portuguese and in 1580, its lord,Omura Sumitada,the first Japanese lord to convert to Christianity,leased itto theJesuits"in perpetuity".[14]The city subsequently evolved from an unimportant fishing village to a prosperous and cosmopolitan community, the entirety of which was Christian.[14]In time, the city would be graced with a painting school, a hospital, a charitable institution (theMisericórdia) and a Jesuit college.

Vessels

[edit]

Among the vessels involved in the trade linking Goa and Japan, the most famous were Portuguesecarracks,slow but large enough to hold a great deal of merchandise and enough provisions to travel safely through such a lengthy and often hazardous (because of pirates) journey. These ships initially had about 400–600 tons burden but later on could reach as many as over 1200 or 1600 tons in cargo capacity, a rare few reaching as many as 2000 tons — they were the largest vessels afloat on Earth, and easily twice or three times larger than common galleons of the time, rivalled only in size by the SpanishManila galleons.[15][16]Many of these were built at the royal Indo-Portuguese shipyards atGoa,BasseinorDaman,out of high-quality Indianteakwoodrather than European pine, and their build quality became renowned; the Spanish in Manila favoured Portuguese-built vessels,[16]and commented that they were not only cheaper than their own, but "lasted ten times as long".[17]

The Portuguese referred to this vessel as thenau da prata( "silver carrack" ) ornau do trato( "trade carrack" ); the Japanese dubbed themkurofune,meaning "black ships",on account of the colour of their hulls, painted black withpitchfor water-tightening, and later the name was extended to refer toMatthew C. Perry's black warships that reopened Japan to the wider world in 1853.[18]

In the 16th century, large junks belonging to private owners from Macau often accompanied the great ship to Japan, about two or three; these could reach about 400 or 500 tons burden.[18]After 1618, the Portuguese switched to using smaller and more maneuverablepinnacesandgalliots,to avoid interception from Dutch raiders.[18]

Traded goods

[edit]By far the most valuable commodities exchanged in the "nanban trade" were Chinese silks for Japanese silver, which was then traded in China for more silk.[19]Although accurate statistics are lacking, it has been estimated that roughly half of Japan's yearly silver output was exported, most of it through theWokou(Japanese and Chinese),Ryukyuansand Portuguese, amounting to about 18 – 20 tons in silverbullion.[20]The English merchantPeter Mundyestimated that Portuguese investment at Canton ascended to 1,500,000 silvertaelsor 2,000,000Spanish dollars.[21][22]The Portuguese also exported surplus silk from Macau to Goa and Europe via Manila.[22][23]

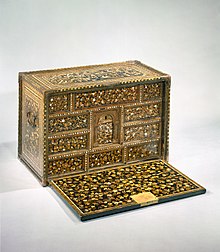

Nonetheless, numerous other items were also transactioned, such as gold, Chineseporcelain,musk,andrhubarb;Arabian horses, Bengal tigers andpeacocks;fine Indian scarlet cloths,calicoandchintz;European manufactured items such as Flemish clocks and Venetian glass and Portuguese wine andrapiers;[24][17]in return for Japanese copper,lacquerandlacquerwareor weapons (as purely exotic items to be displayed in Europe).[25]Japanese lacquerwareattracted European aristocrats and missionaries from Europe, and western style chests and church furniture were exported in response to their requests.[26]

Japanese and other Asians captured in battle were also sold by their compatriots to the Portuguese as slaves, but the Japanese would also sell family members they could not afford to sustain because of the civil-war. According to Prof.Charles Boxer,both old and modern Asian authors have "conveniently overlooked" their part in the enslavement of their countrymen.[27][28]They were well regarded for their skills and warlike character, and some ended as far as India and even Europe, some armed retainers or as concubines or slaves to other slaves of the Portuguese.[29][30]

In 1571,King Sebastian of Portugalissued a ban on the enslavement of both Chinese and Japanese, probably fearing the negative effects it might have on proselytization efforts as well as the standing diplomacy and trade between the countries.[31][32][28]Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the de facto ruler of Japan, enforced the end of the enslavement of his countrymen starting in 1587 and it was suppressed shortly thereafter.[32][33][34]However, Hideyoshi later sold Korean prisoners of war captured during theJapanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598)as slaves to the Portuguese.[35][36]

The overall profits from the Japan trade, carried on through the black ship, was estimated to ascend to over 600,000cruzados,according to various contemporary authors such asDiogo do Couto,Jan Huygen van LinschotenandWilliam Adams.A captain-major who invested at Goa 20,000cruzadosto this venture could expect 150,000cruzadosin profits upon returning.[37]The value of Portuguese exports from Nagasaki during the 16th century were estimated to ascend to over 1,000,000cruzados,reaching as many as 3,000,000 in 1637.[38]The Dutch estimated this was the equivalent of some 6,100,000guilders,almost as much as the entire founding capital of theDutch East India Company(VOC) (6,500,000 guilders).[39]VOC profits in all of Asia amounted to "just" about 1,200,000 guilders, all its assets worth 9,500,000 guilders.[39]

The monopoly of Portugal on trade with Japan for a European nation started being challenged by Spanish ships from Manila after 1600 (until 1620[40]), the Dutch after 1609 and the English in 1613 (until 1623[41]). Nonetheless, it was found that neither the Dutch nor the Spanish could effectively replace the Portuguese because Portugal had privileged access to Chinese markets and investors through Macau.[11]The Portuguese were only definitively banned in 1638 after theShimabara Rebellion,on the grounds that they smuggled priests into Japan aboard their vessels.

Dutch trade

[edit]TheDutch,who, rather than"Nanban"were called"Kōmō"(Jp: Hồng mao, lit. "Red Hair" ) by the Japanese, first arrived in Japan in 1600, on board theLiefde( "liefde"meaning" love "). Their pilot wasWilliam Adams,the first Englishman to reach Japan.

In 1605, two of theLiefde's crew were sent toPattaniby Tokugawa Ieyasu, to invite Dutch trade to Japan. The head of the Pattani Dutch trading post, Victor Sprinckel, refused on the ground that he was too busy dealing with Portuguese opposition in Southeast Asia. In 1609 however, the DutchmanJacques Specxarrived with two ships in Hirado, and through Adams obtained trading privileges from Ieyasu.

TheDutchalso engaged in piracy and naval combat to weakenPortugueseand Spanish shipping in the Pacific, and ultimately became the only westerners to be allowed access to Japan from the small enclave ofDejimaafter 1639 and for the next two centuries.

Technological and cultural exchanges

[edit]

The Japanese were introduced to several new technologies and cultural practices (so were the Europeans to Japanese, seeJaponisme), whether in the military area (thearquebus,cannon,European-stylecuirasses,European ships such asgalleons), religion (Christianity),decorative art,language (integration to Japanese of aWestern vocabulary) and culinary: thePortugueseintroduced thetempuraand European-style confectionery, creatingnanbangashi(Nam Man quả tử),"southern barbarian confectionery", with confectioneries likecastella,konpeitō,aruheitō,karumera,keiran sōmen,bōroandbisukauto.Other traded goods brought by Europeans to Japan were clocks, soap, tobacco, among other products.

Tanegashima guns

[edit]

One of the many things that the Japanese were interested in were Portuguese hand-heldguns.The first two Europeans to reach Japan in the year 1543 were the Portuguese tradersAntónio da Motaand Francisco Zeimoto (Fernão Mendes Pintoclaimed to have arrived on this ship as well, but this is in direct conflict with other data he presents), arriving on a Chinese ship at the southern island ofTanegashimawhere they introduced hand-held guns for trade. The Japanese were already familiar withgunpowderweaponry (invented by, and transmitted from China), and had been using basic Chinese originated guns and cannon tubes called "Teppō"( thiết pháo" Iron cannon ") for around 270 years before the arrival of the Portuguese. In comparison, the Portuguese guns were light, had amatchlockfiring mechanism, and were easy to aim. Because the Portuguese-made firearms were introduced into Tanegashima, thearquebuswas ultimately calledTanegashimain Japan. At that time, Japan was in the middle of a civil war called theSengoku period(Warring States period).

Within a year after the first trade in guns, Japanese swordsmiths and ironsmiths managed to reproduce the matchlock mechanism and mass-produce the Portuguese guns. Early issues due to Japanese inexperience was corrected with the help of Portuguese blacksmiths. The Japanese soon worked on various techniques to improve the effectiveness of their guns and even developed larger caliber barrels and ammunition to increase lethality. Barely fifty years later, Japanese armies dwarfed any contemporary European army in the use of guns. The daimyo who initiated the unification of Japan,Oda Nobunaga,made extensive use of guns (arquebus) when playing a key role in theBattle of Nagashino,as dramatised inAkira Kurosawa's 1980 filmKagemusha(Shadow Warrior). Guns were also strongly instrumental in the unification efforts ofToyotomi HideyoshiandTokugawa Ieyasu,as well as in theinvasions of Koreain 1592 and 1597.

Red seal ships

[edit]European ships (galleons) were also quite influential in the Japanese shipbuilding industry and actually stimulated many Japanese ventures abroad.

The Shogunate established a system of commercial ventures on licensed ships calledred seal ships(Chu ấn thuyền,shuinsen),which sailed throughout East and Southeast Asia for trade. These ships incorporated many elements of galleon design, such as sails, rudder, and gun disposition. They brought to Southeast Asian ports many Japanese traders and adventurers, who sometimes became quite influential in local affairs, such as the adventurerYamada NagamasainSiam,or later became Japanese popular icons, such asTenjiku Tokubei.

By the beginning of the 17th century, the shogunate had built, usually with the help of foreign experts, several ships of purelyNanbandesign, such as the galleonSan Juan Bautista,which crossed the Pacific two times on embassies toNueva España(Mexico).

Catholicism in Japan

[edit]

With the arrival of the leadingJesuitFrancis Xavierin 1549, Catholicism progressively developed as a major religious force in Japan. Although the tolerance of Western "padres" was initially linked to trade, Catholics could claim around 200,000 converts by the end of the 16th century, mainly located in the southern island ofKyūshū.The Jesuits managed to obtain jurisdiction over the trading city ofNagasaki.

The first reaction from thekampakuHideyoshicame in 1587 when he promulgated the interdiction of Christianity and ordered the departure of all "padres". This resolution was not followed upon however (only 3 out of 130 Jesuits left Japan), and the Jesuits were essentially able to pursue their activities. Hideyoshi had written that:

- "1. Japan is a country of the Gods, and for the padres to come hither and preach a devilish law, is a reprehensible and devilish thing...

- 2. For the padres to come to Japan and convert people to their creed, destroying Shinto and Buddhist temples to this end, is a hitherto unseen and unheard-of thing... to stir the canaille to commit outrages of this sort is something deserving of severe punishment. "(From Boxer,The Christian Century in Japan)

Hideyoshi's reaction to Christianity proved stronger when the SpanishgalleonSan Felipewas wrecked in Japan in 1597. The incident led totwenty-six Christians(6 Franciscans, 17 of their Japanese neophytes, and 3 Japanese Jesuit lay brothers – included by mistake) being crucified inNagasakion February 5, 1597. It seems Hideyoshi's decision was taken following encouragements by the Jesuits to expel the rival order, his being informed by the Spanish that military conquest usually followed Catholic proselytism, and by his own desire to take over the cargo of the ship. Although close to a hundred churches were destroyed, most of the Jesuits remained in Japan.

The final blow came withTokugawa Ieyasu's firm interdiction of Christianity in 1614, which led to underground activities by theJesuitsand to their participation inHideyori's revolt in thesiege of Osaka(1614–1615). Repression of Catholicism became virulent after Ieyasu's death in 1616, leading to the torturing and killing of around 2,000 Christians (70 westerners and the rest Japanese) and the apostasy of the remaining 200–300,000. The last major reaction of the Christians in Japan was theShimabara rebellionin 1637. Thereafter, Catholicism in Japan was driven underground as the so-called "Hidden Christians".

OtherNanbaninfluences

[edit]The Nanban also had various other influences:

- Nanbandō(Nam Man đỗng) designates a type of cuirass covering the trunk in one piece, a design imported from Europe.

- Nanbanbijutsu(Nam Man mỹ thuật) generally describes Japanese art with Nanban themes or influenced by Nanban designs.

- Nanbanga( Nam Man họa ) designates the numerous pictorial representations that were made of the new foreigners and defines a whole style category in Japanese art.

- Nanbannuri( Nam Man đồ り) describes lacquers decorated in the Portuguese style, which were very popular items from the late 16th century.

- Namban-ryōri( Nam Man liệu lý ) refers to dishes that use ingredients introduced by the Portuguese and Spanish, such as Spanish pepper, winter onion, corn or pumpkin, as well as methods of preparation such as deep-frying (e.g.tempura).

- Nanbangashi(Nam Man quả tử) is a variety of sweets derived from Portuguese or Spanish recipes. The most popular sweets are "Kasutera"(カステラ), named afterCastile,and "Konpeitō"( kim bình đường こんぺいとう), from the Portuguese word"confeito"(" sugar candy "), and"Biscuit"(ビスケット), etc. These" Southern barbarian "sweets are on sale in many Japanese supermarkets today.

- NanbanjiorNanbandera(Nam Man chùa)was the firstChristianchurch in Kyoto. With support fromOda Nobunaga,theJesuitPadreGnecchi-Soldo Organtinoestablished this church in 1576. Eleven years later (1587), Nanbanji was destroyed byToyotomi Hideyoshi.Currently, the bell is preserved as "Nanbanji-no-kane"Shunkoin templein Kyoto.

- Nanbanzuke( Nam Man tí ) is a dish of fried fish marinated in vinegar, thought to be derived from the Portugueseescabeche.

- Namban-ryū geka( Nam Man lưu ngoại khoa ), Japanese “Southern Barbarian-style surgery,” which adopted some wound plasters and the use of palm oil, pig fat, tobacco, etc. from the Portuguese. However, as a result of the increasingly severe persecution of Christians since the end of the 16th century, this status remained. In the middle of the 17th century, these Western elements were then incorporated into the newly emerged surgery in the style of the redheads ( hồng mao lưu ngoại khoakōmō-ryū geka), i.e. the Dutch one.

- Namban-byōbu( Nam Man bình phong ), "Southern Barbarian screens",multi-part screens on which two motifs dominate: (a) the arrival of a Portuguese ship and (b) the procession of the landed foreigners through the port city.

- Chikin nanban(チキン Nam Man) is a dish of fried battered chicken dipped in a vinegary sauce derived fromnanbanzukeand served withtartar sauce.Invented inMiyazakiin the 1960s, it is now widely popular across Japan.[43]

Linguistic exchange

[edit]The intensive exchange with the “southern barbarians” did not remain without influence on the Japanese vocabulary. Some loanwords fromPortugueseandDutchhave survived to this day:pan(パン, from pão, bread),tempura( thiên ぷら, from tempero, seasoning),botan(ボタン, from botão, button),karuta(カルタ, from cartas de jogar, playing cards),furasuko(フラスコ, from frasco, flask, bottle),marumero(マルメロ, from marmelo, quince), etc. Some words are now only used in scientific texts or in historical context, e.g.iruman(イルマン, from irmão, brother in a Christian order),kapitan(カピタン, from capitão, captain),kirishitan(キリシタン, from christão, Christian),rasha(ラシャ, from raxa, type of cotton fabric),shabon(シャボン, from sabão, soap). Some things from the New World came to Japan along with their names via the Portuguese and Spanish, such as:tabako(タバコ, from tabaco,tobaccoderived from theTaínoof the Caribbean). Some terms only known to experts today only became extinct in the 19th century:porutogaru-yu(ポルトガル du, Portugal oil, i.e. olive oil),chinta(チンタ, from vinho tinto, red wine),empurasuto(エンプラスト, from emprasto, plaster),unguento(ウングエント, from unguento, ointment).

Decline ofNanbanexchanges

[edit]

After the country was pacified and unified byTokugawa Ieyasuin 1603 however, Japan progressively closed itself to the outside world, mainly because of the rise ofChristianity.

In 1639, trade with Portugal was definitively prohibited and the Netherlands became the only European nation to be allowed in Japan. By 1650, except for the trade outpost ofDejimainNagasaki,for the Netherlands, and some trade with China, foreigners were subject to the death penalty, and Christian converts were persecuted. Guns were almost completely eradicated to revert to the more "civilized" sword.[citation needed]Travel abroad and the building of large ships were also prohibited. Thence started a period of seclusion, peace, prosperity and mild progress known as theEdo period.But not long after, in the 1650s, the production ofJapanese export porcelainincreased greatly when civil war put the main Chinese center of porcelain production,in Jingdezhen,out of action for several decades. For the rest of the 17th century mostJapanese porcelainproduction was inKyushufor export through the Chinese and Dutch. The trade dwindled under renewed Chinese competition by the 1740s, before resuming after the opening of Japan in the 1850s.[44]

The "barbarians" would come back 250 years later, strengthened by industrialization, and end Japan's isolation with the forcible opening of Japan to trade by an American military fleet under the command of CommodoreMatthew Perryin 1854.

Usages of the word "Nanban"

[edit]

Nanbanis aSino-Japanese wordderived from the Chinese termNánmán,originally referring to the peoples ofSouth AsiaandSoutheast Asia.The Japanese use ofNanbantook a new meaning when it came to designate the early Portuguese who first arrived in 1543, and later extended to other Europeans that arrived in Japan. The termNanbanhas its origins from theFour Barbariansin theHua–Yi distinctionin the 3rd century in China. Pronunciation of the Chinese Character isJapanised,the đông di (Dōngyí) "Eastern Barbarians" called "Tōi" (it includes Japan itself), Nam Man (Nánmán) "Southern Barbarians" called "Nanban", Tây Nhung (Xīróng) "Western Barbarians" called "Sei-Jū", and Běidí Bắc Địch "Northern Barbarians" called "Hoku-Teki". AlthoughNanbanjust meant Southeast Asia during the Sengoku and Edo periods, through time the word turned into the meaning "Western person", and "from Nanban" means "Exotic and Curious".

Strictly speaking,Nanbanmeans "Portuguese or Spanish" who were the most popular western foreigners in Japan, while other western people were sometimes called "Hồng mao người" (Kō-mōjin) "red-haired people" but Kō-mōjin was not as widespread asNanban.In China, "Hồng mao" is pronouncedAng moinHokkienand is a racist word againstwhite people.Japan later decided to Westernize radically in order to better resist the West and essentially stopped considering the West as fundamentally uncivilized. Words like "Yōfu"( dương phong" western style ") and"Ōbeifu"( Âu mễ phong" European-American style ") replaced"Nanban"in most usages.

Still, the exact principle of westernization wasWakon-Yōsai( cùng hồn dương mới "Japanese spirit Western talent" ), implying that, although technology may be more advanced in the West, Japanese spirit is better than the West's. Hence though the West may be lacking, it has its strong points, which takes the affront out of calling it "barbarian."

Today the word "Nanban"is only used in a historical context, and is essentially felt as picturesque and affectionate. It can sometimes be used jokingly to refer to Western people or civilization in a cultured manner.

There is an area whereNanbanis used exclusively to refer to a certain style and that is cooking and the names of dishes. Nanban dishes are not American or European, but an odd variety not usingsoy sauceormisobut rather curry powder and vinegar as their flavoring, a characteristic derived from Indo-PortugueseGoan cuisine.This is because when Portuguese and Spanish dishes were imported into Japan, dishes from Macau and other parts of China were imported as well.

Timeline

[edit]- 1543 – Portuguese sailors (among them possiblyFernão Mendes Pinto) arrive inTanegashimaand transmit thearquebus.

- 1549 –Francis Xavierarrives inKagoshimaand introduces Christianity.

- 1556 –Luis de Almeidabuilds the first hospital, with Western medicine, in Ōita

- 1557 – Establishment ofMacauby the Portuguese. Dispatch of annual trading ships to Japan.

- 1560 –Siege of Moji,theOtomo clanunsuccessfully attempt to seize theMōricastle of Moji with three Portuguese ships.

- 1563 –Luís Fróisarrives in Japan.

- 1565 –Battle of Fukuda Bay,the first recorded naval clash between the Europeans and the Japanese

- 1570 – Japanese pirates occupy parts ofTaiwan,from where they prey on China.

- 1571 –DaimyōŌmura Sumitadaassists the Portuguese in establishing the port ofNagasaki.

- 1575 –Battle of Nagashino,where firearms are used extensively.

- 1576 – Japan's first cannon is presented toŌtomo Sōrinby Portugal.

- 1577 – First Japanese ships travel toDang Trong,southern Vietnam.

- –João Rodriguesarrives in Japan.

- 1579 – TheJesuitAlessandro Valignanoarrives in Japan.

- 1580 – Ōmura Sumitada cedes Nagasaki "in perpetuity" to theSociety of Jesus.

- – Spain and Portugal enter in adynastic union.

- –Franciscansfrom Japan escape toVietnam.

- 1582 –Tenshō embassyto Europe departs from Nagasaki.

- 1584 –Mancio Itōarrives inLisbonwith three other Japanese, accompanied by a Jesuit father. He was the first Japanese envoy to Europe.

- 1587 –Toyotomi Hideyoshiissues a document declaring the expulsion of Portuguese missionaries and freedom of trade.

- 1588 – Hideyoshi prohibits piracy.

- 1592 – Japan invadesKoreain theSeven-Year Warwith an army of 160.000.

- – First known mention ofRed Seal Ships.

- 1597 –Martyrdom of 26 Christians(essentiallyFranciscans) inNagasaki.

- 1598 – Death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

- 1600 – Arrival ofWilliam Adamson theLiefde.

- – TheBattle of Sekigaharaunites Japan underTokugawa Ieyasu.

- 1602 –Dutchwarships attack the Portuguese carrackSanta CatarinanearPortuguese Malacca.

- 1603 – Establishment ofEdoas the seat ofBakufugovernment.

- – Establishment of the Englishfactory (trading post)atBantam,Java.

- –Nippo JishoJapanese to Portuguese dictionary is published by Jesuits in Nagasaki, containing entries for 32,293 Japanese words in Portuguese.

- 1605 – Two of William Adams's shipmates are sent toPattaniby Tokugawa Ieyasu, to invite Dutch trade to Japan.

- 1609 – The Dutch open a trading factory inHirado.

- 1610 – Destruction of theNossa Senhora da Graçanear Nagasaki, leading to a 2-year hiatus in Portuguese trade

- 1612 –Yamada Nagamasasettles inAyutthaya,Siam.

- 1613 – England opens a trading factory in Hirado.

- –Hasekura Tsunenagaleaves for his embassy to theAmericasand Europe. He returns in 1620.

- 1614 – Expulsion of theJesuitsfrom Japan. Prohibition of Christianity.

- 1615 – Japanese Jesuits start to proselytise inVietnam.

- 1616 – Death ofTokugawa Ieyasu.

- 1622 – Mass martyrdom of 55 Christians (Great Genna Martyrdom).

- – Death ofHasekura Tsunenaga.

- 1623 – The English close their factory at Hirado, because of unprofitability.

- –Yamada Nagamasasails fromSiamto Japan, with an Ambassador of the Siamese kingSongtham.He returns to Siam in 1626.

- – Prohibition of trade with the SpanishPhilippines.

- – Martyrdom of 50 Christians (Great Edo Martyrdom)

- 1624 – Interruption of diplomatic relations with Spain.

- – Japanese Jesuits start to proselytise in Siam.

- 1628 – Destruction of Takagi Sakuemon's ( cao mộc làm hữu vệ môn ) Red Seal ship inAyutthaya,Siam, by a Spanish fleet. Portuguese trade in Japan is prohibited for 3 years as a reprisal.

- 1632 – Death of Tokugawa Hidetada.

- 1634 – On orders of shōgunIemitsu,the artificial islandDejimais built to constrain Portuguese merchants living in Nagasaki.

- 1637 –Shimabara Rebellionby Christian peasants.

- 1639 – Definitive prohibition of trade with Portugal as result of Shimabara Rebellion blamed on Catholic intrigues.

- 1640 – Portugalleavesits 60-year dynastic union with Spain

- 1641 – The Dutch trading factory is moved from Hirado to Dejima island.

See also

[edit]- History of the Catholic Church in Japan

- Nanban art

- Japanese–Portuguese conflicts

- Japan-Netherlands relations

- Japan-Spain relations

- Japan-Portugal relations

- Sengoku period

Notes

[edit]- ^Frequently referred to today in scholarship askaikin,or "maritime restrictions", more accurately reflecting the booming trade that continued during this period and the fact that Japan was far from "closed" or "secluded."

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^"Quá điền thuần 『 cận đại Đông Nam アジア thế giới の 変 dung ――グローバル kinh tế とジャワ đảo địa vực xã hội 』 Nagoya đại học xuất bản sẽ 2014 năm ix+505 trang".Southeast Asia: History and Culture.2016(45): 164–167. 2016.doi:10.5512/sea.2016.45_164.ISSN0386-9040.

- ^Perrin 1979,p. 7

- ^Boxer 1951,p. 11.

- ^First European Description of Life in Japan // 1585 'Striking Contrasts' Luis Frois – Primary Source.Voices of the Past.YouTube. 7 March 2020.

- ^Marcouin, Francis; Omoto, Keiko (1990).Quand le Japon s'ouvrit au monde(in French). Paris: Découvertes Gallimard. pp. 114–116.ISBN2-07-053118-X.

- ^Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine

- ^Valignano, Alessandro(1584).Historia del Principio y Progreso de la Compañía de Jesús en las Indias Orientales.

- ^Easton, Matt (3 October 2018).Japanese 'Samurai' Swords in Period European Eyes.Scola Gladiatoria.YouTube.

- ^Easton, Matt (17 April 2017).Katana vs Sabre: More European accounts of Japanese swords and sword fighting.Scola Gladiatoria.YouTube.

- ^abBoxer 1951,p. 91.

- ^abBoxer 1951,p. 303.

- ^Boxer 1951,p. 92.

- ^Boxer 1951,p. 98.

- ^abBoxer 1951,p. 101.

- ^Boxer 1963,p. 13.

- ^abBoxer 1968,p. 14.

- ^abBoxer 1968,p. 15.

- ^abcBoxer 1963,p. 14.

- ^Boxer 1963,p. 5.

- ^Boxer 1963,p. 7.

- ^The dollar or yuan is 0.72 tael; seeyuan (currency)#Early history

- ^abBoxer 1963,p. 6.

- ^Boxer 1963,pp. 7–8.

- ^Boxer 1968,p. 10.

- ^Boxer 1968,p. 16.

- ^"Urushi once attracted the world".Urushi Nation Joboji.Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2019.

- ^Boxer 1968,p. 223.

- ^abHoffman, Michael (26 May 2013).«The rarely, if ever, told story of Japanese sold as slaves by Portuguese traders».The Japan Times (Arq. em WayBack Machine)

- ^Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis Jr., eds. (2005).Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience(illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 479.ISBN0-19-517055-5.Retrieved2 February2014.

- ^Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis, eds. (2010).Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1(illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 187.ISBN978-0-19-533770-9.Retrieved2 February2014.

- ^Dias 2007,p. 71

- ^abNelson, Thomas (Winter 2004). "Slavery in Medieval Japan".Monumenta Nipponica.59(4). Sophia University: 463–492.JSTOR25066328.

- ^Kitagawa, Joseph Mitsuo (2013).Religion in Japanese History(illustrated, reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 144.ISBN978-0-231-51509-2.Retrieved2 February2014.

- ^Calman, Donald (2013).Nature and Origins of Japanese Imperialism.Routledge. p. 37.ISBN978-1-134-91843-0.Retrieved2 February2014.

- ^Lidin, Olof G. (2002).Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan.Routledge. p. 170.ISBN1-135-78871-5.Retrieved2 February2014.

- ^Stanley, Amy (2012).Selling Women: Prostitution, Markets, and the Household in Early Modern Japan.Asia: Local Studies / Global Themes. Vol. 21. University of California Press.ISBN978-0-520-95238-6.Retrieved2 February2014.

- ^Boxer 1963,p. 8.

- ^Boxer 1963,p. 169.

- ^abBoxer 1963,p. 170.

- ^Boxer 1951,p. 301.

- ^Boxer 1963,p. 4.

- ^Vie, Michel (2004).Histoire du Japon(in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. p. 72.ISBN2-13-052893-7.

- ^"Chicken Nanban (チキン Nam Man )".10 May 2021.

- ^Battie, David,ed.,Sotheby's Concise Encyclopedia of Porcelain,pp. 71-78, 1990, Conran Octopus.ISBN1850292515

- ^"E-Museum - Nanban (Western style) Armor".

Sources

[edit]- Boxer, Charles Ralph(1951).The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650.University of California Press.

- Boxer, Charles Ralph(1963).The Great Ship from Amacon – Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555–1640.Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos.

- Boxer, Charles Ralph(1968).Fidalgos on the Far-East 1550–1770.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-638074-2.

- Dias, Maria Suzette Fernandes (2007),Legacies of slavery: comparative perspectives,Cambridge Scholars Publishing,ISBN978-1-84718-111-4

- Perrin, Noel (1979).Giving Up the Gun: Japan's Reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879.Boston: David R. Godine Publisher.ISBN0-87923-773-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Samurai,Mitsuo Kure, Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo.ISBN0-8048-3287-0

- The Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy. Development and Technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War,Christopher Howe, The University of Chicago Press.ISBN0-226-35485-7

- Yoshitomo Okamoto,The Namban Art of Japan,translated by Ronald K. Jones, Weatherhill/Heibonsha, New York & Tokyo, 1972

- José Yamashiro,Choque luso no Japão dos séculos XVI e XVII,Ibrasa, 1989

- Armando Martins Janeira,O impacto português sobre a civilização japonesa,Publicações Dom Quixote, Lisboa, 1970, 1988

- Wenceslau de Moraes,Relance da história do Japão,2ª ed., Parceria A. M. Pereira Ltda, Lisboa, 1972

- They came to Japan, an anthology of European reports on Japan, 1543–1640,ed. by Michael Cooper, University of California press, 1995

- João Rodrigues's Account of Sixteenth-Century Japan,ed. by Michael Cooper, London: The Hakluyt Society, 2001 (ISBN0-904180-73-5)

External links

[edit]- The Wakasa tale: an episode occurred when guns were introduced in Japan, F. A. B. Coutinho

- Tanegashima: the arrival of Europe in Japan,Olof G. Lidin, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, NIAS Press, 2002

- Nanban folding screens

- Nanban art(Japanese)

- Japanese Art and Western Influence

- Shunkoin Templethe Bell of Nanbanji

- Japan Mint:2005 International Coin Design Competition, Jury's Special Award – "The Meeting of Cultures" by Vitor Santos (Portugal)

- 16th century in Japan

- 17th century in Japan

- Economy of feudal Japan

- Foreign trade of Japan

- History of international trade

- History of the foreign relations of Japan

- Japan in non-Japanese culture

- Japan–Portugal relations

- Jesuit Asia missions

- Portuguese exploration in the Age of Discovery

- Portuguese non-fiction literature