Narwhal

| Narwhal | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

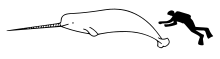

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Monodontidae |

| Genus: | Monodon Linnaeus,1758 |

| Species: | M. monoceros

|

| Binomial name | |

| Monodon monoceros | |

| |

| Distribution of narwhal populations | |

Thenarwhal(Monodon monoceros) is aspeciesoftoothed whalenative to theArctic.It is the only member of thegenusMonodon,and one of two living representatives of the familyMonodontidae.The narwhal has a similar build to the closely relatedbeluga whale,with which it overlaps in range and caninterbreed.It has a stocky body with a prominentmelon,reduced flippers, a shallow dorsal ridge, and mottled brown-and-white colouration. It issexually dimorphic;adult males are larger than females and have a singletuskthat can be up to 3 m (9.8 ft) long. The tusk, which is derived from the leftcanine,is thought to serve as a weapon or as a tool for feeding,attracting matesor sensing water salinity. The jointedneck vertebraeand shallow dorsal ridge may allow for agile movements under the ice, or help reducesurface areaand heat loss.

The narwhal inhabitsArctic watersof Canada, Greenland and Russia. Every year, itmigratesto ice-free summering grounds, usually in shallow waters, and oftenreturnsto the same sites in subsequent years. Its diet mainly consists ofpolarandArctic cod,Greenland halibut,cuttlefish,shrimp,andarmhook squid.Plunging at depths of up to 2,370 m (7,780 ft), the narwhal is among the deepest-divingcetaceans.It travels in groups of three to eight, with aggregations of up to 1,000 occurring in the summer months. The narwhal mates in the offshorepack icefrom March to May, and the young are born in July or August of the following year. When communicating, a variety of clicks, whistles and knocks are used.

There are an estimated 170,000 living narwhals, and the species is listed as being ofleast concernby theInternational Union for Conservation of Nature(IUCN). The population is threatened by theeffects of climate change,such as thereduction in ice cover,and human activities such aspollutionandhunting.The narwhal has been hunted for thousands of years byInuitin northern Canada and Greenland formeatandivory,and regulated subsistence hunts continue.

Taxonomy

The narwhal was scientifically described byCarl Linnaeusin his 1758Systema Naturae.[5]One of the earliest illustrations of the species is a 1555 drawing byOlaus Magnusdepicting a fish-like creature with a horn on its forehead; Magnus called it "Monoceros".[6][7]The word "narwhal" comes from theOld Norsenárhval,meaning 'corpse-whale', which possibly refers to the animal's grey, mottled skin[8][9]and its habit of remaining motionless when at the water's surface, a behaviour known as "logging" that usually happens in the summer.[8]The scientific name,Monodon monoceros,is derived fromGreek:'single-tooth single-horn'.[10]

The narwhal is most closely related to thebeluga whale(Delphinapterus leucas). Together, these two species comprise the onlyextantmembers of the familyMonodontidae,sometimes referred to as the "white whales". TheMonodontidaeare distinguished by their pronouncedmelons(acoustic sensory organs), shortsnoutsand the absence of a truedorsal fin.[11][12]A 2020phylogenetic studybased onmitochondrial DNAsuggested that, around 4.98million years ago(mya), the narwhal split from the beluga whale.[13]

Although the narwhal and beluga are classified as separate genera, there is some evidence that they may, very rarely,interbreed.The remains of an abnormal-looking whale, described by marine zoologists as unlike any known species, were found in West Greenland around 1990. It had features midway between a narwhal and a beluga, indicating that the remains belonged to anarluga(a hybrid between the two species);[14]this was confirmed by a 2019DNA analysis.[15]Whether the hybridcould breedremains unknown.[16][14]

Results of a genetic study reveal thatporpoisesand white whales are closely related, forming a separatecladewhich diverged fromdolphinsabout 11 million years ago.[17]Molecular analysis ofMonodontidaefossils indicate that they had separated fromPhocoenidaearound 10.82 to 20.12 mya; they are considered to be asister taxon.[18]

The fossil speciesCasatia thermophilaofearly Pliocenecentral Italy was described as a possible narwhal ancestor when it was discovered in 2019.Bohaskaia,DenebolaandHaborodelphisare other extinct genera known during thePlioceneof the eastern and western United States.[19][20][21]Fossil evidence shows that ancient white whales lived in tropical waters. They may have migrated to Arctic and subarctic waters in response to changes in the marine food chain.[20]

The followingphylogenetic treeis based on a 2019 study of the familyMonodontidae.[19]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

The narwhal has a thickset body with a short, blunt snout, small upcurved flippers, and convex to concave tail flukes.[22][23][24]Adults measure in body-to-tail length from 3.0 to 5.5 m (9.8 to 18.0 ft) and weigh 800 to 1,600 kg (1,800 to 3,500 lb). They exhibitsexual dimorphism,with males being larger than females. The body is made up of denseblubberthat ranges in thickness from 50 to 100 mm (2.0 to 3.9 in); this blubber may account for a third of the body mass.[25][24][22]Male narwhals attainsexual maturityat 11 to 13 years of age, reaching a length of 3.9 m (13 ft). Females become sexually mature at a younger age, between 5 and 8 years old, when they are about 3.4 m (11 ft) long.[26]

Thepigmentationof the narwhal is amottled pattern,with blackish-brown markings over a white background.[9]At birth, the skin is light grey, and when sexually mature, white patches grow on thenavelandgenital slit.With age, this variegated colouring gradually fades, turning the skin to an almost pure white state.[23][27]Unlike most whales, the narwhal has a shallow dorsal ridge, rather than a dorsal fin. This is possibly anevolutionary adaptationto make swimming under ice easier, to facilitate rolling, or to reducesurface areaand heat loss.[28][29]The narwhal's neckvertebraeare jointed, instead of being fused together as in most whales; this allows a great range of neck flexibility. These characteristics—a dorsal ridge and jointed neck vertebrae—are shared by the beluga whale.[12]Male and female narwhals have different tail flukes; the former are bent inward, while the latter have a sweep-back on the front margins. This is thought to be an adaptation for reducingdragcaused by the tusk.[24]

Compared with most marine mammals, the narwhal has a higher amount ofmyoglobinin its body, which facilitates deeper dives.[30]Itsskeletal muscleis adapted to withstand prolonged periods of deep-sea foraging. During such activities, oxygen is reserved in the muscles, which are typicallyslow-twitch,allowing for endurance and manoeuvrable motion.[31]

Tusk

The most conspicuous characteristic of the male narwhal is a long, spiralled tusk, which is acanine tooth[32]that projects from the left side of the upper jaw.[33]Both sexes are born with a pair of tusks embedded in the upper jaw, which in males erupts at two or three.[23][34]The tusk grows throughout a male's life, reaching a length of 1.5 to 3 m (4.9 to 9.8 ft).[35][36][37]It is hollow and weighs up to 7.45 kg (16.4 lb). Some males may grow two tusks, occurring when the right canine also protrudes through the lip.[34]Females rarely grow tusks: when they do, the tusks are typically smaller than those of males, with less noticeable spirals.[38][39]

The function of the narwhal tusk is debated. Some biologists suggest that narwhals use their tusks in fights, while others argue that they may be of use in feeding. There is, however, ascientific consensusthat tusks aresecondary sexual characteristicswhich indicate social status.[40]The tusk is also a highlyinnervatedsensory organwith millions ofnerve endingsthat connect seawater stimuli to the brain, allowing the narwhal to sense temperature variability in its surroundings.[32]These nerves may be able to pick up the slightest increase or decrease in the magnitude of particles and water pressure.[41][42]According to a 2014 study, male narwhals may exchangeinformationabout the properties of the water they have travelled through by rubbing their tusks together, as opposed to the previously assumed posturing display of aggressive male-to-male rivalry.[32]Dronefootage from August 2016 in Tremblay Sound,Nunavut,revealed that narwhals used their tusks to tap andstunsmallArctic cod,making them easier to catch for feeding.[43][40]Females, who usually do not have tusks, live longer than males, hence the tusk cannot be essential to the animal's survival. It is generally accepted that the primary function of the narwhal tusk is associated withsexual selection.[44]

Vestigial teeth

The narwhal has a single pair of smallvestigialteeth that reside in open tooth sockets in the upper jaw. These teeth, which differ in form and composition, encircle the exposed tooth sockets laterally, posteriorly, and ventrally.[32][45]Vestigial teeth in male narwhals are commonly shed in thepalate.The varied morphology and anatomy of small teeth indicate a path of evolutionary obsolescence.[32][46]

Distribution

The narwhal is found in the Atlantic and Russian areas of theArctic Ocean.Individuals are commonly recorded in theCanadian Arctic Archipelago,[47][48]such as in the northern part ofHudson Bay,Hudson Strait,Baffin Bay;off the east coast of Greenland; and in a strip running east from the northern end of Greenland round to eastern Russia (170° east). Land in this strip includesSvalbard,Franz Joseph LandandSevernaya Zemlya.[9]The northernmost sightings of narwhals have occurred north of Franz Joseph Land, at about85° north.[9]There are an estimated 12,500 narwhals in northern Hudson Bay, whereas around 140,000 reside in Baffin Bay.[49]

Migration

Narwhals exhibitseasonal migration,with a highfidelity of returnto preferred ice-free summering grounds, usually in shallow waters. In summer months, they move closer to coasts, often in pods of 10–100. In the winter, they move to offshore, deeper waters under thickpack ice,surfacing in narrow fissures or in wider fractures known asleads.[50]As spring comes, these leads open up into channels and the narwhals return to the coastalbays.[51]Narwhals in Baffin Bay typically travel further north, to northern Canada and Greenland, between June and September. After this period, they travel about 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi) south to theDavis Strait,and stay there until April.[49]During winter, narwhals from Canada and West Greenland regularly visit the pack ice of the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay along thecontinental slopewhich contains less than 5% open water and hosts high densities ofGreenland halibut.[52]

Behaviour and ecology

Narwhals normallycongregate in groupsof three to eight—and sometimes up to twenty—individuals. Groups may be "nurseries" with only females and young, or can contain only post-dispersaljuveniles or adult males ( "bulls" ); mixed groups can occur at any time of year.[22][12]In the summer, several groups come together, forming larger aggregations which can contain 500 to over 1,000 individuals.[25][23]Male narwhals have been observed rubbing each other's tusks, a behaviour known as "tusking".[41][53]

When in their wintering waters, narwhals make some of the deepest dives recorded for cetaceans, diving to at least 800 m (2,620 ft) over 15 times per day, with many dives reaching 1,500 m (4,920 ft).[54][55]The greatest dive depth recorded is 2,370 m (7,780 ft).[54][56]Dives last up to 25 minutes, but can vary in depth, depending on the season and local variation between environments. For example, in the Baffin Bay wintering grounds, narwhals tend to dive deep within the precipitous coasts, typically south of Baffin Bay. This suggests differences in habitat structure, prey availability, or genetic adaptations between subpopulations. In the northern wintering grounds, narwhals do not dive as deep as the southern population, in spite of greater water depths in these areas. This is mainly attributed to prey being concentrated nearer to the surface, which causes narwhals to alter their foraging strategies.[54]

Diet

Compared with other marine mammals, narwhals have a relatively restricted and specialised diet.[57][50]Due to the lack of well-developeddentition,narwhals are believed to feed by swimming close to prey andsuckingthem into the mouth.[58]A study of the stomach contents of 73 narwhals found Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida) to be the most commonly consumed prey, followed by Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides). Large quantities of Boreo-Atlantic armhook squid (Gonatus fabricii) were discovered. Males were more likely than females to consume two additional prey species: polar cod (Arctogadus glacialis) and redfish (Sebastes marinus), both of which are found in depths of more than 500 m (1,600 ft). The study also concluded that the size of prey did not differ among genders or ages.[59]Other items found in stomachs have includedwolffish,capelin,skateeggs and sometimes rocks.[25][52][50]

Narwhal diet varies by season. In winter, narwhals feed ondemersalprey, mostlyflatfish,under dense pack ice. During the summer, they eat mostly Arctic cod and Greenland halibut, with other fish such as polar cod making up the remainder of their diet.[59]Narwhals consume more food in the winter months than they do in summer.[52][50]

Breeding

Most female narwhals reproduce by the time they are six to eight years old.[8]Courtshipandmatingbehaviour for the species has been recorded from March to May, when they are in offshore pack ice, and is thought to involve a dominant male mating with several partners. The averagegestationlasts 15 months; births appear to be most frequent between July and August. A female has a birth interval of around 2–3 years.[26][60][61]As with most marine mammals, only a single young is born, averaging 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in length with white or light grey pigmentation.[62][63]Summer population surveys along different coastal inlets ofBaffin Islandfound that calf numbers varied from 0.05% of 35,000 inAdmiralty Inlet,to 5% of 10,000 total inEclipse Sound.These findings suggest that higher calf counts may reflect calving and nursery habitats in favourable inlets.[64]

Newborn calves begin their lives with a thin layer of blubber. The blubber thickens as theynursetheir mother's milk, which is rich in fat; calves are dependent on milk for about 20 months.[65][25]This long lactation period gives calves time to learn skills they will need to survive as they mature.[65][64]

Narwhals are among the few animals that undergomenopauseand live for decades after they have finished breeding. Females in this phase may continue to protect calves in the pod.[26]A 2024 study concluded that five species ofOdontocetievolved menopause to acquire higher overall longevity, though their reproductive periods did not change. To explain this, scientists hypothesised that calves of the five Odontoceti species require the assistance of menopausal females for an enhanced chance at survival, as they are extremely difficult for a single female to successfully rear.[66]

Communication

Like most toothed whales, narwhals use sound to navigate and hunt for food. They primarily vocalise through clicks, whistles and knocks, created by air movement between chambers near theblowhole.[67]The frequency of these sounds ranges from 0.3 to 125hertz,while those used forecholocationtypically fall between 19 and 48 hertz.[68][69]Sounds are reflected off the sloping front of the skull and focused by the animal's melon, which can be controlled through surrounding musculature.[70]Echolocation clicks are used for detecting prey and locating barriers at short distances.[71]Whistles and throbs are most commonly used to communicate with other pod members.[72]Calls recorded from the same pod are more similar than calls from different pods, suggesting the possibility of group- or individual-specific calls. Narwhals sometimes adjust the duration and pitch of their pulsed calls to maximise sound propagation in varying acoustic environments.[73][74]Other sounds produced by narwhals include trumpeting and "squeaking-door sounds".[8]The narwhal vocal repertoire is similar to that of the beluga whale. However, the frequency ranges, durations, and repetition rates of narwhal clicks differ from those of belugas.[75]

Longevity and mortality factors

Age determination techniques using the number ofperiosteumlayers in thelower jawreveal that narwhals live an average of 50 years, though techniques usingamino acid datingfrom thelensof the eyes suggest that female narwhals can reach 115±10 years and male narwhals can live to 84±9 years.[76]

Death bysuffocationoften occurs when narwhals fail to migrate before theArctic freezes overin late autumn. This is known as "sea-ice entrapment".[25][77]Narwhals drown if open water is no longer accessible and ice is too thick for them to break through. Breathing holes in ice may be up to 1,450 m (4,760 ft) apart, which limits the use of foraging grounds. These holes must be at least 0.5 m (1.6 ft) wide to allow an adult whale to breathe.[30]Narwhals also die ofstarvationfrom entrapment events.[25]

In 1914–1915, around 600 narwhal carcasses were discovered after entrapment events, most occurring in areas such asDisko Bay.In the largest entrapment in 1915 inWest Greenland,over 1,000 narwhals were trapped under the ice.[78]Several cases of sea entrapment were recorded in 2008–2010, during the Arctic winter, including in some places where such events had never been recorded before.[77]This suggests later departure dates from summering grounds. Wind and currents move sea ice from adjacent locations to Greenland, leading to fluctuations in concentration. Due to their tendency of returning to the same areas, changes in weather and ice conditions are not always associated with narwhal movement toward open water. It is currently unclear to what extent sea ice changes pose a danger to narwhals.[77][79][57]

Narwhals are preyed upon bypolar bearsandorcas.In some instances, the former have been recorded waiting at breathing holes for young narwhals, while the latter were observed surrounding and killing entire narwhal pods.[25][80][81][82]To escape predators such as orcas, narwhals may use prolonged submersion to hide underice floesrather than relying on speed.[30]

Researchers foundBrucellain the bloodstreams of numerous narwhals throughout the course of a 19-year study. They were also recorded withwhale licespecies such asCyamus monodontisandCyamus nodosus.OtherpathogensincludeToxoplasma gondii,morbillivirus,andpapillomavirus.[83]In 2018, a female narwhal hadAlpha herpesvirusin her system.[84]

Conservation

The narwhal is listed as a species ofleast concernby theIUCN Red List.As of 2017, the global population is estimated to be 123,000 mature individuals out of a total of 170,000. There were about 12,000 narwhals in Northern Hudson Bay in 2011, and around 49,000 nearSomerset Islandin 2013. There are approximately a total of 35,000 inAdmiralty Inlet,10,000 in Eclipse Sound, 17,000 inEastern Baffin Bay,and 12,000 inJones Sound.Population numbers inSmith Sound,Inglefield BredningandMelville Bayare 16,000, 8,000 and 3,000, respectively. There are roughly 800 narwhals in the waters off Svalbard.[3]

In the 1972Marine Mammal Protection Act,the United States banned imports of products made from narwhal parts.[3]They are listed on Appendix II of theConvention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora(CITES) andConvention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals(CMS). These committees restrict international trading of live animals and their body parts, as well as implement sustainable action plans.[3][4][85]The species is also classified as special concern under theCommittee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada(COSEWIC), which aims to classify the risk levels of species in the country.[49][86]

Threats

Narwhals are hunted for their skin,meat,teeth, tusks andcarved vertebrae,which are commercially traded. About 1,000 narwhals are killed per year: 600 in Canada and 400 in Greenland. Canadian catches were steady at this level in the 1970s, dropped to 300–400 per year in the late 1980s and 1990s and have risen again since 1999. Greenland caught more, 700–900 per year, in the 1980s and 1990s.[87]

Narwhal tusks are sold both carved and uncarved in Canada[88][89]and Greenland.[90]Per hunted narwhal, an average of one or two vertebrae and one or two teeth are sold.[88]In Greenland, the skin (muktuk) is sold commercially tofish factories,[90]and in Canada to other communities.[88]One estimate of the annual gross value received from narwhal hunts in Hudson Bay in 2013 wasCA$6,500(US$6,300) per narwhal, of whichCA$4,570(US$4,440) was for skin and meat. The net income after subtracting costs in time and equipment, was a loss ofCA$7(US$6.80) per narwhal. Hunts receivesubsidies,but they continue mainly to support tradition, rather than for profit. Economic analysis noted thatwhale watchingmay be an alternate source of revenue.[88]

As narwhals grow,bioaccumulationof heavy metals takes place.[91]It is thought thatpollution in the oceanis the primary cause of bioaccumulation in marine mammals; this may lead to health problems for the narwhal population.[92]When bioaccumulating, numerous metals appear in the blubber, liver, kidney and musculature. A study found that the blubber was nearly devoid of these metals, whereas the liver and kidneys had a dense concentration of them. Relative to the liver, the kidney has a greater concentration ofzincandcadmium,whilelead,copperandmercurywere not nearly as abundant. Individuals of different weight and sex showed dissimilarities in the concentration of metals in their organs.[93]

Narwhals are one of the Arctic marine mammals most vulnerable toclimate change[51]due to sea ice decline, especially in their northern wintering grounds such as the Baffin Bay and Davis Strait regions. Satellite data collected from these areas shows the amount of sea ice has been markedly reduced from what it was previously.[94]It is thought that narwhals' foraging ranges reflect patterns they acquired early in life, which improves their capacity to obtain the food supplies they need for the winter. This strategy focuses on strongsite fidelityrather than individual-level responses to local prey distribution, resulting in focal foraging areas during the winter. As such, despite changing conditions, narwhals will continue to return to the same areas during migration.[94]As narwhals emerged during thelate Plioceneepoch, they must have undergone adaptation toglacialsand climate change.[95]

Reduction in sea ice has possibly led to increased exposure to predation. In 2002, hunters inSiorapalukexperienced an increase in the number of caught narwhals, but this increase did not seem to be linked to enhanced endeavour,[96]implying that climate change may be making the narwhal more vulnerable to hunting. Scientists recommend assessing population numbers, assigning sustainablequotas,and ensuring local acceptance of sustainable development.Seismic surveysassociated withoil explorationdisrupt the narwhal's normal migration patterns. These disturbed migrations may also be associated with increased sea ice entrapment.[97]

Relationship with humans

Narwhals have coexisted alongsidecircumpolar peoplesfor millennia.[9]Their long, distinctive tusks were often held with fascination throughout human history.[98]Depictions of narwhals in paintings such asThe Lady and the Unicornhave found a prevalent place inart.[99]The ivory tusks were prized for their supposed healing powers, and were worn on staffs and thrones.[100]

Inuit

Narwhals have been hunted byInuitto the same extent as other sea mammals, such assealsandwhales.Almost all parts of the narwhal—the meat, skin, blubber and organs—are consumed.Muktuk,the raw skin and attached blubber, is considered a delicacy. As a custom, one or two vertebrae per animal are used for tools andart.[88][9]The skin is an important source ofvitamin C,which is otherwise difficult to obtain in the Arctic Circle. In some places in Greenland, such asQaanaaq,traditional hunting methods are used and whales areharpoonedfrom handmadekayaks.In other parts of Greenland and Northern Canada,high-speed boatsandhunting riflesare used.[9]

InInuit legend,the narwhal's tusk was created when a woman with harpoon rope tied around her waist was dragged into the ocean after the harpoon had stuck into a large narwhal. She was thentransformedinto a narwhal; her hair, which she was wearing in atwisted knot,became the spiralling narwhal tusk.[101]

Tusk trade

The narwhal tusk has been highly sought-after in Europe for centuries. This stems from a medieval belief that narwhal tusks were thehornsof the legendaryunicorn.[102][103][104]According to some theories,VikingsandGreenland Norsebegan trade of narwhal tusks, which, via European channels, would later reach markets in theMiddle EastandEast Asia.The idea thatNorsemenhunted narwhals was once held, but was never confirmed and is now considered improbable.[105][106]

Across medieval Europe, narwhal tusks were given as state gifts to kings and queens.[103]In the 18th and 19th centuries, the price tag of tusks was said to be a couple of hundred times greater than its weight ingold.[100]Ivan the Terriblehad a jewellery-covered narwhal tusk on his deathbed,[103]whileElizabeth Ireceived one reportedly valued at £10,000pounds sterling[107]from theprivateerMartin Frobisher,who proposed that the tusk was from a "sea-unicorne". Both items were staples incabinets of curiosities.[108][109]

Considered to have magical properties, narwhal tusks were used to counter poisoning, and all sorts of diseases such asmeaslesandrubella.[99][110][111]The rise of science towards the end of the 17th century led to a decreased belief inmagicandalchemy.After the unicorn notion was scientifically refuted, narwhal tusks were rarely employed for magical purposes.[112][113]

References

- ^Newton, Edwin Tulley (1891).The Vertebrata of the Pliocene deposits of Britain.London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.doi:10.5962/bhl.title.57425.

- ^"Monodon monoceros Linnaeus 1758 (narhwal)".PBDB.org.Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2020.Retrieved11 July2020.

- ^abcdLowry, L.; Laidre, K.; Reeves, R. (2017)."Monodon monoceros".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2017.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T13704A50367651.en.

- ^ab"Appendices | CITES".cites.org.Archivedfrom the original on 5 December 2017.Retrieved14 January2022.

- ^Linnaeus, Carl(1758)."Monodon monoceros".Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata(in Latin). Stockholm: Lars Salvius. p. 75.

- ^Bamforth, Stephen (September 2010)."On Gesner, marvels and unicorns".Nottingham French Studies.49(3): 110–145.doi:10.3366/nfs.2010-3.010.ISSN0029-4586.

- ^Olaus; Olaus; Grapheus, Cornelius Scribonius; Beller, Jean (1557).Historiae de gentibus septentrionalibus.Antverpiae: Apud Ioannem Bellerum. p. 481.

- ^abcd"The narwhal: unicorn of the seas"(PDF).Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2007.Archived(PDF)from the original on 10 July 2013.Retrieved10 July2013.

- ^abcdefgHeide-Jørgensen, M. P.; Laidre, K. L. (2006).Greenland's Winter Whales: The Beluga, the Narwhal and the Bowhead Whale.Ilinniusiorfik Undervisningsmiddelforlag, Nuuk, Greenland. pp. 100–125.ISBN87-7975-299-3.

- ^Webster, Noah (1880)."Narwhal".An American Dictionary of the English Language.G. & C. Merriam. p. 854.

- ^Brodie, Paul (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Mammals.New York: Facts on File. pp.200–203.ISBN0-87196-871-1.

- ^abcNowak, Ronald M. (2003).Walker's marine mammals of the world.Internet Archive. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 135–137.ISBN978-0-8018-7343-0.

- ^Louis, Marie; Skovrind, Mikkel; Samaniego Castruita, Jose Alfredo; Garilao, Cristina; Kaschner, Kristin; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Haile, James S.; Lydersen, Christian; Kovacs, Kit M.; Garde, Eva; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Postma, Lianne; Ferguson, Steven H.; Willerslev, Eske; Lorenzen, Eline D. (29 April 2020)."Influence of past climate change on phylogeography and demographic history of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) ".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.287(1925): 20192964.doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2964.ISSN0962-8452.PMC7211449.PMID32315590.

- ^abHeide-Jørgensen, Mads P.; Reeves, Randall R. (July 1993)."Description of an anomalous Monodontid skull from West Greenland: a possible hybrid?".Marine Mammal Science.9(3): 258–268.Bibcode:1993MMamS...9..258H.doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1993.tb00454.x.ISSN0824-0469.

- ^Skovrind, Mikkel; Castruita, Jose Alfredo Samaniego; Haile, James; Treadaway, Eve C.; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Westbury, Michael V.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Szpak, Paul; Lorenzen, Eline D. (20 June 2019)."Hybridization between two high Arctic cetaceans confirmed by genomic analysis".Scientific Reports.9(1): 7729.Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7729S.doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44038-0.ISSN2045-2322.PMC6586676.PMID31221994.

- ^Pappas, Stephanie (20 June 2019)."First-ever beluga–narwhal hybrid found in the Arctic".Live Science.Archivedfrom the original on 20 June 2019.Retrieved20 June2019.

- ^Waddell, Victor G.; Milinkovitch, Michel C.; Bérubé, Martine; Stanhope, Michael J. (1 May 2000)."Molecular phylogenetic examination of theDelphinoideatrichotomy: congruent evidence from three nuclear loci indicates that porpoises (Phocoenidae) share a more recent common ancestry with white whales (Monodontidae) than they do with true dolphins (Delphinidae) ".Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.15(2): 314–318.Bibcode:2000MolPE..15..314W.doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0751.ISSN1055-7903.PMID10837160.

- ^Racicot, Rachel A.; Darroch, Simon A. F.; Kohno, Naoki (October 2018)."Neuroanatomy and inner ear labyrinths of the narwhal,Monodon monoceros,and beluga,Delphinapterus leucas(Cetacea:Monodontidae) ".Journal of Anatomy.233(4): 421–439.doi:10.1111/joa.12862.ISSN0021-8782.PMC6131972.PMID30033539.

- ^abBianucci, Giovanni; Pesci, Fabio; Collareta, Alberto; Tinelli, Chiara (4 May 2019)."A newMonodontidae(Cetacea,Delphinoidea) from the lower Pliocene of Italy supports a warm-water origin for narwhals and white whales ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.39(3): e1645148.Bibcode:2019JVPal..39E5148B.doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1645148.hdl:11568/1022436.ISSN0272-4634.S2CID202018525.Retrieved21 January2024.

- ^abVélez-Juarbe, Jorge; Pyenson, Nicholas D. (1 March 2012)."Bohaskaia monodontoides,a new monodontid (Cetacea,Odontoceti,Delphinoidea) from the Pliocene of the western North Atlantic Ocean ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.32(2): 476–484.Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..476V.doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.641705.ISSN0272-4634.S2CID55606151.

- ^I ăn kít ma, Hiroto; Furusawa, Hitoshi; Tachibana, Makino; Kimura, Masaichi (May 2019). Hautier, Lionel (ed.)."First monodontid cetacean (Odontoceti, Delphinoidea) from the early Pliocene of the north-western Pacific Ocean".Papers in Palaeontology.5(2): 323–342.Bibcode:2019PPal....5..323I.doi:10.1002/spp2.1244.ISSN2056-2799.

- ^abcReeves, Randall R.; Tracey, Sharon (15 April 1980)."Monodon monoceros".Mammalian Species(127): 1–7.doi:10.2307/3503952.ISSN0076-3519.JSTOR3503952.

- ^abcdWebber, Marc A.; Jefferson, Thomas Allen; Pitman, Robert L. (28 July 2015).Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Identification.Academic Press. p. 172.ISBN978-0-12-409592-2.

- ^abcFontanella, Janet E.; Fish, Frank E.; Rybczynski, Natalia; Nweeia, Martin T.; Ketten, Darlene R. (October 2011)."Three-dimensional geometry of the narwhal (Monodon monoceros) flukes in relation to hydrodynamics ".Marine Mammal Science.27(4): 889–898.Bibcode:2011MMamS..27..889F.doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00439.x.hdl:1912/4924.ISSN0824-0469.

- ^abcdefgMacdonald, David Whyte; Barrett, Priscilla (2001).Mammals of Europe.Princeton University Press. p. 173.ISBN0-691-09160-9.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved27 January2024.

- ^abcGarde, Eva; Hansen, Steen H.; Ditlevsen, Susanne; Tvermosegaard, Ketil Biering; Hansen, Johan; Harding, Karin C.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter (7 July 2015)."Life history parameters of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) from Greenland ".Journal of Mammalogy.96(4): 866–879.doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyv110.ISSN0022-2372.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved22 January2024.

- ^"Monodon monoceros".Fisheries and Aquaculture Department: Species Fact Sheets.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived fromthe originalon 16 February 2012.Retrieved20 November2007.

- ^Dietz, Rune; Shapiro, Ari D.; Bakhtiari, Mehdi; Orr, Jack; Tyack, Peter L; Richard, Pierre; Eskesen, Ida Grønborg; Marshall, Greg (19 November 2007)."Upside-down swimming behaviour of free-ranging narwhals".BMC Ecology.7(1): 14.Bibcode:2007BMCE....7...14D.doi:10.1186/1472-6785-7-14.ISSN1472-6785.PMC2238733.PMID18021441.

- ^Werth, Alexander J.; Ford, Jr., Thomas J. (3 July 2012)."Abdominal fat pads act as control surfaces in lieu of dorsal fins in the beluga (Delphinapterus) ".Marine Mammal Science.28(4).doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2012.00567.x.ISSN0824-0469.

- ^abcWilliams, Terrie M.; Noren, Shawn R.; Glenn, Mike (April 2011)."Extreme physiological adaptations as predictors of climate-change sensitivity in the narwhal (Monodon monoceros) ".Marine Mammal Science.27(2): 334–349.Bibcode:2011MMamS..27..334W.doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00408.x.ISSN0824-0469.

- ^Pagano, Anthony M.; Williams, Terrie M. (15 February 2021)."Physiological consequences of Arctic sea ice loss on large marine carnivores: unique responses by polar bears and narwhals".Journal of Experimental Biology.224(Suppl_1).doi:10.1242/jeb.228049.ISSN0022-0949.PMID33627459.

- ^abcdeNweeia, Martin T.; Eichmiller, Frederick C.; Hauschka, Peter V.; Donahue, Gretchen A.; Orr, Jack R.; Ferguson, Steven H.; Watt, Cortney A.; Mead, James G.; Potter, Charles W.; Dietz, Rune; Giuseppetti, Anthony A.; Black, Sandie R.; Trachtenberg, Alexander J.; Kuo, Winston P. (18 March 2014)."Sensory ability in the narwhal tooth organ system".The Anatomical Record.297(4): 599–617.doi:10.1002/ar.22886.ISSN1932-8486.PMID24639076.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^Louis, Marie; Skovrind, Mikkel; Garde, Eva; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Szpak, Paul; Lorenzen, Eline D. (3 February 2021)."Population-specific sex and size variation in long-term foraging ecology of belugas and narwhals".Royal Society Open Science.8(2).Bibcode:2021RSOS....802226L.doi:10.1098/rsos.202226.ISSN2054-5703.PMC8074634.PMID33972883.

- ^abGarde, Eva; Peter Heide-Jørgensen, Mads; Ditlevsen, Susanne; Hansen, Steen H. (January 2012)."Aspartic acid racemization rate in narwhal (Monodon monoceros) eye lens nuclei estimated by counting of growth layers in tusks ".Polar Research.31(1): 15865.doi:10.3402/polar.v31i0.15865.ISSN1751-8369.

- ^Dietz, Rune; Desforges, Jean-Pierre; Rigét, Frank F.; Aubail, Aurore; Garde, Eva; Ambus, Per; Drimmie, Robert; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Sonne, Christian (10 May 2021)."Analysis of narwhal tusks reveals lifelong feeding ecology and mercury exposure".Current Biology.31(9): 2012–2019.e2.Bibcode:2021CBio...31E2012D.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.02.018.ISSN0960-9822.PMID33705717.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2024.Retrieved26 January2024.

- ^Mann, Janet (2000).Cetacean Societies: Field Studies of Dolphins and Whales.University of Chicago Press. p. 247.ISBN0-226-50341-0.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved28 January2024.

- ^Dipper, Frances (2021).The Marine World: A Natural History of Ocean Life.Princeton University Press. p. 437.ISBN978-0-691-23244-7.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved28 January2024.

- ^Charry, Bertrand; Tissier, Emily; Iacozza, John; Marcoux, Marianne; Watt, Cortney A. (4 August 2021)."Mapping Arctic cetaceans from space: a case study for beluga and narwhal".PLOS ONE.16(8): e0254380.Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1654380C.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254380.ISSN1932-6203.PMC8336832.PMID34347780.

- ^Eales, Nellie B. (17 October 1950)."The skull of the foetal narwhal,Monodon monoceros".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences.235(621): 1–33.Bibcode:1950RSPTB.235....1E.doi:10.1098/rstb.1950.0013.ISSN2054-0280.PMID24538734.S2CID40943163.Archivedfrom the original on 20 June 2022.Retrieved26 January2024.

- ^abLoch, Carolina; Fordyce, R. Ewan; Werth, Alexander (2023), Würsig, Bernd; Orbach, Dara N. (eds.), "Skulls, teeth, and sex",Sex in Cetaceans: Morphology, Behavior, and the Evolution of Sexual Strategies,Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 51–64,doi:10.1007/978-3-031-35651-3_3,ISBN978-3-031-35651-3

- ^abBroad, William (13 December 2005)."It's sensitive. Really".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved22 February2017.

- ^Vincent, James (19 March 2014)."Scientists suggest they have the answer to the mystery of the narwhal's tusk".Independent.co.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2022.Retrieved31 March2014.

- ^"Drone-shot video may have just solved 400-year debate over what narwhal tusks are used for".National Post.17 May 2017.Retrieved17 July2024.

{{cite news}}:CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^Kelley, Trish C.; Stewart, Robert E. A.; Yurkowski, David J.; Ryan, Anna; Ferguson, Steven H. (April 2015)."Mating ecology of beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) and narwhal (Monodon monoceros) as estimated by reproductive tract metrics ".Marine Mammal Science.31(2): 479–500.Bibcode:2015MMamS..31..479K.doi:10.1111/mms.12165.ISSN0824-0469.

- ^"For a dentist, the narwhal's smile is a mystery of evolution".Smithsonian Insider. 18 April 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2016.Retrieved6 September2016.

- ^Nweeia, Martin T.; Eichmiller, Frederick C.; Hauschka, Peter V.; Tyler, Ethan; Mead, James G.; Potter, Charles W.; Angnatsiak, David P.; Richard, Pierre R.; Orr, Jack R.; Black, Sandie R. (30 March 2012)."Vestigial tooth anatomy and tusk nomenclature forMonodon Monoceros".The Anatomical Record.295(6): 1006–1016.doi:10.1002/ar.22449.ISSN1932-8486.PMID22467529.

- ^Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. (2018),"Narwhal:Monodon monoceros",in Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M.; Kovacs, Kit M. (eds.),Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Third Edition),Academic Press, pp. 627–631,ISBN978-0-12-804327-1,archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2023,retrieved27 January2024

- ^Belikov, Stanislav E.; Boltunov, Andrei N. (21 July 2002)."Distribution and migrations of cetaceans in the Russian Arctic according to observations from aerial ice reconnaissance".NAMMCO Scientific Publications.4:69–86.doi:10.7557/3.2838.ISSN2309-2491.Archivedfrom the original on 27 January 2024.Retrieved27 January2024.

- ^abcWatt, C. A.; Orr, J. R.; Ferguson, S. H. (January 2017)."Spatial distribution of narwhal (Monodon monoceros) diving for Canadian populations helps identify important seasonal foraging areas ".Canadian Journal of Zoology.95(1): 41–50.doi:10.1139/cjz-2016-0178.ISSN0008-4301.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved20 January2024.

- ^abcdLaidre, K. L.; Heide-Jorgensen, M. P. (January 2005)."Winter feeding intensity of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) ".Marine Mammal Science.21(1): 45–57.Bibcode:2005MMamS..21...45L.doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2005.tb01207.x.ISSN0824-0469.

- ^abLaidre, Kristin L.; Stirling, Ian; Lowry, Lloyd F.; Wiig, Øystein; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Ferguson, Steven H. (March 2008)."Quantifying the sensitivity of Arctic marine mammals to climate-induced habitat change".Ecological Applications.18(sp2): S97–S125.Bibcode:2008EcoAp..18S..97L.doi:10.1890/06-0546.1.ISSN1051-0761.PMID18494365.

- ^abcLaidre, K. L.; Heide-Jørgensen, M. P.; Jørgensen, O. A.; Treble, M. A. (1 January 2004)."Deep-ocean predation by a high Arctic cetacean".ICES Journal of Marine Science.61(3): 430–440.Bibcode:2004ICJMS..61..430L.doi:10.1016/j.icesjms.2004.02.002.ISSN1095-9289.

- ^"The biology and ecology of narwhals".noaa.gov.National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.Archivedfrom the original on 14 August 2022.Retrieved15 January2009.

- ^abcLaidre, Kristin L.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Dietz, Rune; Hobbs, Roderick C.; Jørgensen, Ole A. (17 October 2003)."Deep-diving by narwhals (Monodon monoceros): differences in foraging behavior between wintering areas? ".Marine Ecology Progress Series.261:269–281.Bibcode:2003MEPS..261..269L.doi:10.3354/meps261269.ISSN0171-8630.

- ^Kumar, Mohi (March 2011)."Research Spotlight: Narwhals document continued warming of Baffin Bay".Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union.92(9): 80.Bibcode:2011EOSTr..92...80K.doi:10.1029/2011EO090009.ISSN0096-3941.

- ^Davis, Randall W. (2019). "Appendix 3. Maximum Recorded Dive Depths and Durations for Marine Mammals".Marine Mammals. Adaptations for an Aquatic Life.Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.ISBN978-3319982786.

- ^abChambault, P.; Tervo, O. M.; Garde, E.; Hansen, R. G.; Blackwell, S. B.; Williams, T. M.; Dietz, R.; Albertsen, C. M.; Laidre, K. L.; Nielsen, N. H.; Richard, P.; Sinding, M. H. S.; Schmidt, H. C.; Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. (29 October 2020)."The impact of rising sea temperatures on an Arctic top predator, the narwhal".Scientific Reports.10(1): 18678.Bibcode:2020NatSR..1018678C.doi:10.1038/s41598-020-75658-6.ISSN2045-2322.PMC7596713.PMID33122802.

- ^Jensen, Frederik H.; Tervo, Outi M.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Ditlevsen, Susanne (25 March 2023)."Detecting narwhal foraging behaviour from accelerometer and depth data using mixed-effects logistic regression".Animal Biotelemetry.11(1): 14.Bibcode:2023AnBio..11...14J.doi:10.1186/s40317-023-00325-2.ISSN2050-3385.

- ^abFinley, K. J.; Gibb, E. J. (December 1982). "Summer diet of the narwhal (Monodon monoceros) in Pond Inlet, northern Baffin Island ".Canadian Journal of Zoology.60(12): 3353–3363.doi:10.1139/z82-424.ISSN0008-4301.

- ^Klinowska, Margaret, ed. (1991).Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book.IUCN. p. 79.ISBN2-88032-936-1.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved28 January2024.

- ^Würsig, Bernd; Rich, Jacquline; Orbach, Dara N. (2023), Würsig, Bernd; Orbach, Dara N. (eds.), "Sex and Behavior",Sex in Cetaceans: Morphology, Behavior, and the Evolution of Sexual Strategies,Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–27,doi:10.1007/978-3-031-35651-3_1,ISBN978-3-031-35651-3

- ^Tinker, Spencer Wilkie (1988).Whales of the World.E. J. Brill. p. 213.ISBN0-935848-47-9.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved28 January2024.

- ^Mann, Janet (1 January 2009), Perrin, William F.; Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. (eds.),"Parental Behavior",Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Second Edition),London: Academic Press, pp. 830–836,ISBN978-0-12-373553-9,retrieved17 July2024

- ^abEvans Ogden, Lesley (6 January 2016)."Elusive narwhal babies spotted gathering at Canadian nursery".New Scientist.Archivedfrom the original on 21 September 2016.Retrieved6 September2016.

- ^abZhao, Shu-Ting; Matthews, Cory J. D.; Davoren, Gail K.; Ferguson, Steven H.; Watt, Cortney A. (24 June 2021)."Ontogenetic profiles of dentine isotopes (δ15N and δ13C) reveal variable narwhal Monodon monoceros nursing duration".Marine Ecology Progress Series.668:163–175.doi:10.3354/meps13738.ISSN0171-8630.

- ^Ellis, Samuel; Franks, Daniel W.; Nielsen, Mia Lybkær Kronborg; Weiss, Michael N.; Croft, Darren P. (13 March 2024)."The evolution of menopause in toothed whales".Nature.627(8004): 579–585.Bibcode:2024Natur.627..579E.doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07159-9.ISSN1476-4687.PMC10954554.PMID38480878.

- ^Blackwell, Susanna B.; Tervo, Outi M.; Conrad, Alexander S.; Sinding, Mikkel H. S.; Hansen, Rikke G.; Ditlevsen, Susanne; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter (13 June 2018)."Spatial and temporal patterns of sound production in East Greenland narwhals".PLOS ONE.13(6): e0198295.Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1398295B.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198295.ISSN1932-6203.PMC5999075.PMID29897955.

- ^Still, Robert; Harrop, Hugh; Dias, Luís; Stenton, Tim (2019).Europe's Sea Mammals Including the Azores, Madeira, the Canary Islands and Cape Verde: A field guide to the whales, dolphins, porpoises and seals.Princeton University Press. p. 16.ISBN978-0-691-19062-4.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved28 January2024.

- ^Miller, Lee A.; Pristed, John; Møshl, Bertel; Surlykke, Annemarie (October 1995)."The click-sounds of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in Inglefield Bay, Northwest Greenland ".Marine Mammal Science.11(4): 491–502.Bibcode:1995MMamS..11..491M.doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1995.tb00672.x.ISSN0824-0469.S2CID85148204.Archivedfrom the original on 5 October 2022.Retrieved27 January2024.

- ^Senevirathna, Jayan Duminda Mahesh; Yonezawa, Ryo; Saka, Taiki; Igarashi, Yoji; Funasaka, Noriko; Yoshitake, Kazutoshi; Kinoshita, Shigeharu; Asakawa, Shuichi (January 2021)."Transcriptomic insight into the melon morphology of toothed whales for aquatic molecular developments".Sustainability.13(24): 13997.doi:10.3390/su132413997.ISSN2071-1050.

- ^Zahn, Marie J.; Rankin, Shannon; McCullough, Jennifer L. K.; Koblitz, Jens C.; Archer, Frederick; Rasmussen, Marianne H.; Laidre, Kristin L. (12 November 2021)."Acoustic differentiation and classification of wild belugas and narwhals using echolocation clicks".Scientific Reports.11(1): 22141.Bibcode:2021NatSR..1122141Z.doi:10.1038/s41598-021-01441-w.ISSN2045-2322.PMC8589986.PMID34772963.

- ^Marcoux, Marianne; Auger-Méthé, Marie; Humphries, Murray M. (October 2012)."Variability and context specificity of narwhal (Monodon monoceros) whistles and pulsed calls ".Marine Mammal Science.28(4): 649–665.Bibcode:2012MMamS..28..649M.doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2011.00514.x.ISSN0824-0469.

- ^Lesage, Véronique; Barrette, Cyrille; Kingsley, Michael C. S.; Sjare, Becky (January 1999)."The effect of vessel noise on the vocal behavior of belugas in the St. Lawrence river estuary, Canada".Marine Mammal Science.15(1): 65–84.Bibcode:1999MMamS..15...65L.doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00782.x.ISSN0824-0469.

- ^Shapiro, Ari D. (1 September 2006)."Preliminary evidence for signature vocalizations among free-ranging narwhals (Monodon monoceros) ".The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.120(3): 1695–1705.Bibcode:2006ASAJ..120.1695S.doi:10.1121/1.2226586.hdl:1912/2355.ISSN0001-4966.

- ^Jones, Joshua M.; Frasier, Kaitlin E.; Westdal, Kristin H.; Ootoowak, Alex J.; Wiggins, Sean M.; Hildebrand, John A. (1 March 2022)."Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) and narwhal (Monodon monoceros) echolocation click detection and differentiation from long-term Arctic acoustic recordings ".Polar Biology.45(3): 449–463.Bibcode:2022PoBio..45..449J.doi:10.1007/s00300-022-03008-5.ISSN1432-2056.S2CID246176509.

- ^Garde, Eva; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Hansen, Steen H.; Nachman, Gösta; Forchhammer, Mads C. (28 February 2007)."Age-specific growth and remarkable longevity in narwhals (Monodon monoceros) from West Greenland as estimated by aspartic acid racemization ".Journal of Mammalogy.88(1): 49–58.doi:10.1644/06-mamm-a-056r.1.ISSN0022-2372.

- ^abcLaidre, Kristin; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Stern, Harry; Richard, Pierre (1 January 2012)."Unusual narwhal sea ice entrapments and delayed autumn freeze-up trends".Polar Biology.35(1): 149–154.Bibcode:2012PoBio..35..149L.doi:10.1007/s00300-011-1036-8.ISSN1432-2056.S2CID253807718.

- ^Porsild, Morten P. (1918)."On 'savssats': a crowding of Arctic animals at holes in the sea ice".Geographical Review.6(3): 215–228.Bibcode:1918GeoRv...6..215P.doi:10.2307/207815.ISSN0016-7428.JSTOR207815.

- ^Macdonald, David Whyte; Barrett, Priscilla (1993).Mammals of Britain & Europe.HarperCollins. p. 173.ISBN978-0-00-219779-3.

- ^Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. 'Hans', eds. (2009).Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals.Academic Press. pp. 929–930.ISBN978-0-08-091993-5.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved18 November2020.

- ^Ferguson, Steven H.; Higdon, Jeff W.; Westdal, Kristin H. (30 January 2012)."Prey items and predation behavior of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Nunavut, Canada based on Inuit hunter interviews ".Aquatic Biosystems.8(1): 3.Bibcode:2012AqBio...8....3F.doi:10.1186/2046-9063-8-3.ISSN2046-9063.PMC3310332.PMID22520955.

- ^"Invasion of the killer whales: killer whales attack pod of narwhal".Public Broadcasting System. 19 November 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 22 October 2016.Retrieved23 October2016.

- ^Barratclough, Ashley; Ferguson, Steven H.; Lydersen, Christian; Thomas, Peter O.; Kovacs, Kit M. (July 2023)."A review of circumpolar Arctic marine mammal health—a call to action in a time of rapid environmental change".Pathogens.12(7): 937.doi:10.3390/pathogens12070937.ISSN2076-0817.PMC10385039.PMID37513784.

- ^Nielsen, Ole; Rodrigues, Thaís C. S.; Marcoux, Marianne; Béland, Karine; Subramaniam, Kuttichantran; Lair, Stéphane; Hussey, Nigel E.; Waltzek, Thomas B. (6 July 2023)."Alphaherpesvirus infection in a free-ranging narwhal (Monodon monoceros) from Arctic Canada ".Diseases of Aquatic Organisms.154:131–139.doi:10.3354/dao03732.ISSN0177-5103.PMID37410432.

- ^"Fact sheet narwhal and climate change| CITES"(PDF).cms.int.Archived(PDF)from the original on 26 January 2024.Retrieved21 January2024.

- ^Lukey, James R.; Crawford, Stephen S. (June 2009)."Consistency of COSEWIC species at risk designations: freshwater fishes as a case study".Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences.66(6): 959–971.doi:10.1139/F09-054.ISSN0706-652X.

- ^Witting, Lars (10 April 2017),Meta population modelling of narwhals in East Canada and West Greenland – 2017,doi:10.1101/059691,S2CID89062294,retrieved14 February2024

- ^abcdeHoover, C.; Bailey, M. L.; Higdon, J.; Ferguson, S. H.; Sumaila, R. (2013)."Estimating the economic value of narwhal and beluga hunts in Hudson Bay, Nunavut".Arctic.66(1). Arctic Institute of North America: 1–16.doi:10.14430/arctic4261.ISSN0004-0843.

- ^Greenfieldboyce, Nell (19 August 2009)."Inuit hunters help scientists track narwhals".NPR.org.National Public Radio.Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2016.Retrieved24 October2016.

- ^abHeide-Jørgensen, Mads P. (22 April 1994)."Distribution, exploitation and population status of white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in West Greenland ".Meddelelser om Grønland. Bioscience.39:135–149.doi:10.7146/mogbiosci.v39.142541.ISSN0106-1054.

- ^Wagemann, R.; Snow, N. B.; Lutz, A.; Scott, D. P. (9 December 1983)."Heavy metals in tissues and organs of the narwhal (Monodon monoceros) ".Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences.40(S2): s206–s214.doi:10.1139/f83-326.ISSN0706-652X.

- ^Bouquegneau, Krishna Das; Debacker, Virginie; Pillet, Stéphane Jean-Marie (2003),"Heavy metals in marine mammals",Toxicology of Marine Mammals,CRC Press, pp. 147–179,doi:10.1201/9780203165577-11,hdl:2268/3680,ISBN978-0-429-21746-3,retrieved4 February2024

- ^Dietz, R.; Riget, F.; Hobson, K.; Heidejorgensen, M.; Moller, P.; Cleemann, M.; Deboer, J.; Glasius, M. (20 September 2004)."Regional and inter annual patterns of heavy metals, organochlorines and stable isotopes in narwhals (Monodon monoceros) from West Greenland ".Science of the Total Environment.331(1–3): 83–105.Bibcode:2004ScTEn.331...83D.doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.03.041.ISSN0048-9697.PMID15325143.

- ^abLaidre, Kristin L.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter (10 February 2011)."Life in the lead: extreme densities of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in the offshore pack ice ".Marine Ecology Progress Series.423:269–278.Bibcode:2011MEPS..423..269L.doi:10.3354/meps08941.ISSN0171-8630.

- ^Louis, Marie; Skovrind, Mikkel; Samaniego Castruita, Jose Alfredo; Garilao, Cristina; Kaschner, Kristin; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Haile, James S.; Lydersen, Christian; Kovacs, Kit M.; Garde, Eva; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Postma, Lianne; Ferguson, Steven H.; Willerslev, Eske; Lorenzen, Eline D. (29 April 2020)."Influence of past climate change on phylogeography and demographic history of narwhals, Monodon monoceros".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.287(1925): 20192964.doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2964.ISSN0962-8452.PMC7211449.PMID32315590.

- ^Kovacs, Kit M.; Lydersen, Christian; Overland, James E.; Moore, Sue E. (1 March 2011)."Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals".Marine Biodiversity.41(1): 181–194.Bibcode:2011MarBd..41..181K.doi:10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0.ISSN1867-1624.

- ^Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Hansen, Rikke Guldborg; Westdal, Kristin; Reeves, Randall R.; Mosbech, Anders (February 2013)."Narwhals and seismic exploration: is seismic noise increasing the risk of ice entrapments?".Biological Conservation.158:50–54.Bibcode:2013BCons.158...50H.doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.08.005.ISSN0006-3207.

- ^Canada, Service (13 October 2015)."Narwhal (Monodon monoceros) COSEWIC assessment and status report".canada.ca.Retrieved4 July2024.

- ^abWexler, Philip (2017).Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance.Academic Press. pp. 101–102.ISBN978-0-12-809559-1.

- ^abNweeia, Martin T. (15 February 2024)."Biology and cultural importance of the narwhal".Annual Review of Animal Biosciences.12:187–208.doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-021122-112307.ISSN2165-8110.PMID38358838.

- ^Bastian, Dawn Elaine; Mitchell, Judy K. (2004).Handbook of Native American Mythology.Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 54–55.ISBN1-85109-533-0.

- ^Dugmore, Andrew J.; Keller, Christian; McGovern, Thomas H. (6 February 2007)."Norse Greenland settlement: reflections on climate change, trade, and the contrasting fates of human settlements in the North Atlantic islands".Arctic Anthropology.44(1): 12–36.doi:10.1353/arc.2011.0038.ISSN0066-6939.PMID21847839.S2CID10030083.

- ^abcPluskowski, Aleksander (January 2004)."Narwhals or unicorns? Exotic animals as material culture in medieval Europe".European Journal of Archaeology.7(3): 291–313.doi:10.1177/1461957104056505.ISSN1461-9571.S2CID162878182.

- ^Daston, Lorraine; Park, Katharine (2001).Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750.Zone Books.ISBN0-942299-91-4.

- ^Dectot, Xavier (October 2018)."When ivory came from the seas. On some traits of the trade of raw and carved sea-mammal ivories in the Middle Ages".Anthropozoologica.53(1): 159–174.doi:10.5252/anthropozoologica2018v53a14.ISSN0761-3032.S2CID135259639.

- ^Schmölcke, Ulrich (December 2022)."What about exotic species? Significance of remains of strange and alien animals in the Baltic Sea region, focusing on the period from the Viking Age to high medieval times (800–1300 CE)".Heritage.5(4): 3864–3880.doi:10.3390/heritage5040199.ISSN2571-9408.

- ^Sherman, Josepha (2015).Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore.Routledge. p. 476.ISBN978-1-317-45938-5.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023.Retrieved18 September2023.

- ^Regard, Frédéric, ed. (2014),"Ice and Eskimos: Dealing With a New Otherness",The Quest for the Northwest Passage: Knowledge, Nation and Empire, 1576–1806,Pickering & Chatto,ISBN978-1-84893-270-8,retrieved13 February2024

- ^Duffin, Christopher J. (January 2017)."'Fish', fossil and fake: medicinal unicorn horn ".Geological Society, London, Special Publications.452(1): 211–259.Bibcode:2017GSLSP.452..211D.doi:10.1144/SP452.16.ISSN0305-8719.S2CID133366872.

- ^Rochelandet, Brigitte (2003).Monstres et merveilles de Franche-Comté: fées, fantômes et dragons(in French). Editions Cabédita. p. 131.ISBN978-2-88295-400-8.

- ^Robertson, W. G. Aitchison (1926)."The use of the unicorn's horn, coral and stones in medicine".Annals of Medical History.8(3): 240–248.ISSN0743-3131.PMC7946245.PMID33944492.

- ^Spary, E C (2019)."On the ironic specimen of the unicorn horn in enlightened cabinets".Journal of Social History.52(4): 1033–1060.doi:10.1093/jsh/shz005.ISSN1527-1897.

- ^Schoenberger, Guido (1951)."A goblet of unicorn horn".The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin.9(10): 284–288.doi:10.2307/3258091.ISSN0026-1521.JSTOR3258091.

Further reading

- Ford, John; Ford, Deborah (March 1986). "Narwhal: unicorn of the Arctic seas".National Geographic.Vol. 169, no. 3. pp. 354–363.ISSN0027-9358.OCLC643483454.

- Groc, Isabelle (12 February 2014)."The world's weirdest whale: hunt for the sea unicorn".New Scientist.Retrieved10 February2024.