National Archaeological Museum (Madrid)

Museo Arqueológico Nacional | |

| |

| |

| |

| Established | 20 March 1867 |

|---|---|

| Location | Calle de Serrano,13,Madrid,Spain |

| Coordinates | 40°25′25.122″N3°41′21.919″W/ 40.42364500°N 3.68942194°W |

| Type | Archaeology museum |

| Visitors | 499,300 (2019)[1] |

| Director | Andrés Carretero Pérez |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Museo Arqueológico Nacional |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 1962 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0001373 |

TheNational Archaeological Museum(Spanish:Museo Arqueológico Nacional;MAN) is aarchaeology museuminMadrid,Spain. It is located onCalle de Serranobeside thePlaza de Colón,sharing its building with theNational Library of Spain.It is one of the National Museums of Spain and it is attached to theMinistry of Culture.

History[edit]

The museum was founded in 1867 by a Royal Decree ofIsabella IIas a depository for numismatic, archaeological, ethnographical and decorative art collections of the Spanish monarchs. The establishment of the museum was predated by a previous unmaterialised proposal by theRoyal Academy of Historyin 1830 to create a museum of antiquities.[2]

The museum was originally located in theEmbajadoresdistrict of Madrid. In 1895, it moved to a building designed specifically to house it, aneoclassicaldesign by architectFrancisco Jareño,built from 1866 to 1892. In 1968, renovation and extension works considerably increased its area. The museum closed for renovation in 2008 and reopened in April 2014.[3]

Following a restructuring of the collection in the 1940s, its former pieces relative to the section of American Ethnography were transferred to theMuseum of the Americas,while other pieces from abroad were destined to theNational Museum of Ethnographyand to theNational Museum of Decorative Arts.[4]

Its current collection is based on pieces from theIberian Peninsula,fromPrehistorytoEarly-Modern Age.However, it also has different collections coming from outside of Spain, especially fromAncient Greece,both from the metropolitan and, above all, fromMagna Graecia,and, to a lesser extent, fromAncient Egypt,in addition to "a small number of pieces" fromNear East.[5]

Permanent exhibition[edit]

This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(November 2020) |

Forecourt[edit]

-

Replica of Altamira Cave paintings

In the forecourt is a replica of theCave of Altamirafrom the 1960s.Photogrammetrywas used to reproduce the famous paintings on a mould of the original cave. The replica cave is related to an exhibit at theDeutsches Museumin Munich.[6]

Main building[edit]

Visitors enter the building at basement level, and pass to the prehistory section.

Protohistory[edit]

The halls devoted to the Protohistory of the Iberian Peninsula (1st floor) exhibit pieces froma number of Pre-Roman peoplesexisting roughly along the 1st millennia BC, as well as from the Punic-Phoenician colonisation. The former includes items from theTalaiotic culture,Iberian,Celtic, and Tartessian artifacts. The collection ofIberian sculpturefrom southern and southeastern Iberia is particularly notable, including stone sculptures such as the iconicLady of Elche,theLady of Baza,theLady of Galera,theDama del Cerro de los Santos,theBicha of Balazote,theBull of Osuna,theSphinx of Agost,one of the twosphinxes of El Salobralor theMausoleum of Pozo Moro.[7][8][9][10]

-

Iberianmausoleum of Pozo Moro.

-

Iberian wild boar

Aside from the set of Iberian sculpture, the area also hosts other items from different cultures, such as the Talaiotic bulls of Costitx, the torque of Ribadeo from theCastro culturein northwestern Iberia, or theLady of Ibiza,associated to thePunic civilization.[7]

-

Bull heads of Costitx

-

Torque of Ribadeo

-

PunicLady of Ibiza

-

Wheel of Toya

-

ThePriest of Cadiz.

Roman Hispania[edit]

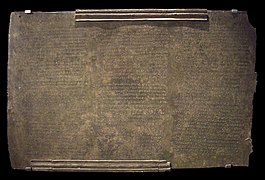

The collection of Hispano-Roman artifacts—located in the 1st floor—comes both from diggings at specific archaeological sites as well as from punctual purchases.[11]The collection of Roman artifacts is completed by items from the personal collection of theMarquis of Salamanca(purchased in 1874 and comprising artifacts from thePaestumandCalessites in the Italian Peninsula).[11][10]The main room of the area is a courtyard, where the artifacts are placed creating a sort offorum-like arrangement.[12]Meanwhile, the room #27 exhibits a number of mosaics both on its floor and walls.[13]The collection of Hispano-Roman legal bronzes includes theLex Ursonensis,comprising five pieces found in the 1870s inOsuna.[14]

-

Mosaic of Winter, fromQuintana del Marco

-

One the slabs part of theLex Ursonensis

-

Mosaic of Medusa and the seasons fromPalencia

-

Hypnos from Algorós

Late Antiquity[edit]

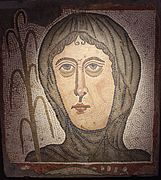

The halls corresponding to theLate Antiquity(1st floor) host pieces related to the period of time corresponding to the Lower Roman Empire in the Iberian Peninsula—theDiocesis Hispaniarum(3rd–5th centuries AD)—, theVisigothic Kingdom of Toledo(6th-8th centuries AD), theByzantine Empire(5th to 12th centuries AD),[15]as well as some artifacts of other peoples from theMigration Period.[16]

Standout artifacts from this area include theSarcophagus from Astorga,the Visigothichoard of Guarrazar,including thevotive crownofRecceswinth,[16]or thefibulae from Alovera.[15]

-

Paleochristiansarcophagus from Astorga

-

Votive crown ofRecceswinth

Medieval World, al-Andalus[edit]

The area dedicated toal-Andalusis located in the 1st floor. Iconic pieces from al-Andalus include thepyxis of Zamora(actually made in Medina Azahara), thedeer-like fountain source of Medina Azaharaor the marble font for ablutions ofAlmanzor.[17]A Jewish bilingual chapitel from Toledo is also exhibited.[18]Two items of the so-calledAlhambra vasesstand out within the collection ofNasrid pottery.[19]

-

Thedeer of Medina Azahara,a bronze fountain

-

Ablution font of Medina Alzahira

-

One of the Alhambra vases

Medieval World, Christian kingdoms[edit]

The area dedicated to the medieval Christian Kingdoms (roughly ranging from the 8th to the 15th century) is located in the 2nd floor. Iconic pieces of Romanesqueivory craftsmanshipinclude theArca de las Bienaventuranzasand theCrucifix of Ferdinand and Sancha.[21]The medieval collection features thepraying statue of Peter I of Castile,made inalabasterand moved from the formerconvent of Santo Domingo el Real in Madridto the National Archaeological Museum in 1868.[22][21]It also displays a number of items ofLevantinepottery.[21]

-

Pottery fromManises

Near East[edit]

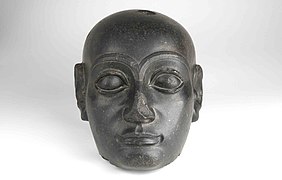

The topic area devoted to theAncient Near East(conventionally excluding Ancient Egypt) is located at the 2nd floor. One of the most important sets of the MAN's Near East collection is that of pottery from Iran.[23]The museum displays adioritehead from Mesopotamia donated to thePrado Museumin the 1940s by the Mexican collectorMarius de Zayas(later deposited in the MAN).[24]21st century purchases include that of thePraying Sumerian figurebought atChristie'sin 2001.[25]

-

Pottery fromTepe Sialk

-

Brick fromGirsudisplayingcuneiform writing

-

Praying Sumerian figure

-

Head of Gudea (Lagash period)

Egypt and Nubia[edit]

The collections ofEgyptandNubiaare made up mainly of funerary funds (amulets,mummies,steles,sculpture of divinities,ushabti...) ranging from prehistory to Roman and medieval times.[26]Many of the pieces come from purchases such as the one made from the collection of the Spanish EgyptologistEduardo Toda y Güell[27]and also from various excavations such as the ones carried in Egypt and Sudan as a result of the agreements with the Egyptian government for the construction of the Aswan Dam[28]or the systematic excavations inHeracleopolis Magna.

-

Stele of Nebsumenu from theSecond Intermediate Period(1650–1550 BC)

-

Basalt sculpture of Harsomtus em hat from thetwenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt.

-

Late periodsarcophagus.

-

Cocodrile baby mummy.

-

Black basalt sculpture ofhorus.

-

Ptolemaic periodsculpture.

Greece[edit]

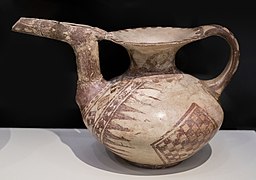

The Greek collection is made up of works from continental Greece, Ionia, Magna Graecia and Sicily, where the collection of bronzes, terracottas, goldsmiths, sculptures and to a greater extentpotterycome from; pieces that ranging from theMycenaeanto theHellenisticperiod.[29]In its beginnings, the collection had funds from the Royal Cabinet of Natural History and theNational Library,the collection was later enriched with works brought from the expeditions of the frigate Arapiles to the East[28]in addition to the purchase of private funds such as those of theMarquis of Salamanca[30]or those of Tomás Asensi.

-

Archaic periodhoplite armor set.

-

Crater of theMadness of Herakles.

-

Dog-headedrhyton.

-

Roman copy of aLyssippusoriginal.

Notable artifacts[edit]

- Prehistoric and Iberian

- Lady of Elche

- Lady of Baza

- Lady of Galera

- Dama del Cerro de los Santos

- Biche of Balazote

- Bull of Osuna

- Magacela stele

- Mausoleum of Pozo Moro

- Sphinx of Agost

- Roman

- Medieval

- Pyxis of Zamora

- One of theAlhambra vases

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^culturaydeporte.gob.es

- ^Lanzarote Guiral, José María (2011). "National Museums in Spain: A History of Crown, Church and People". In Aronsson, Peter; Elgenius, Gabriella (eds.).Building National Museums in Europe 1750–2010(PDF).Linköping University Electronic Press.p. 853.

- ^Official website(in Spanish), plus information from Madrid Tourist Office etc, as at November 24, 2013.

- ^Marcos Alonso, Carmen (2017)."150 años del Museo Arqueológico Nacional"(PDF).Boletín del Museo Arqueológico Nacional(35): 1699.ISSN0212-5544.

- ^"Egipto y Oriente Próximo",Museo Arqueológico Nacional(in Spanish)

- ^"The Deutsches Museum Replica".Retrieved2019-11-21.

- ^ab"Protohistoria"(PDF).pp. 34–51.

- ^Pulido, Natividad (4 March 2012)."Museo Arqueológico Nacional, la nueva joya de la corona cultural en Madrid".ABC.

- ^Prieto, Ignacio M. (2009)."Esfinge de El Salobral"(PDF).

- ^abBeltrán Fortes, José (2007)."El marqués de Salamanca (1811-1883) y su colección escultórica. Esculturas romanas procedentes dePaestumyCales"(PDF).In Beltrán Fortes, José; Cacciotti, Beatrice; Palma, Beatrice (eds.).Arqueología, coleccionismo y antigüedad: España e Italia en el siglo XIX.Universidad de Sevilla. p. 37.ISBN978-84-472-1071-8.

- ^abSalas Álvarez 2015,p. 281.

- ^Salas Álvarez, Jesús (2015)."La Arqueología Hispanorromana en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional"(PDF).ArqueoWeb.16:281.ISSN1139-9201.

- ^Salas Álvarez 2015,p. 283.

- ^Paredes Martín, Enrique; Revilla Hita, Raquel (2019)."Cinco años de investigación, divulgación y colaboración UCM-MAN a través de los bronces legales béticos del Museo"(PDF).Boletín del Museo Arqueológico Nacional.38:300.ISSN2341-3409.

- ^ab"De la Antigüedad a la Edad Media"(PDF).Museo Arqueológico Nacional.

- ^abFranco Mata, Ángela; Balmaseda Muncharaz, Luis; Arias Sánchez, Isabel; Vidal Álvarez, Sergio."Nuevo montaje de la colección de Arqueología y Arte Medieval del Museo Arqueológico Nacional"(PDF).pp. 422–425.

- ^García-Contreras Ruiz, Guillermo (2015)."Al-Andalus en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional: Donde arquitectura y artes decorativas prevalecen por encima de la historia"(PDF).ArqueoWeb.16:296.ISSN1139-9201.

- ^"El mundo medieval. Al-Andalus"(PDF).p. 78.

- ^Franco Mata, Ángela (2014)."Artes suntuarias medievales en el actual montaje del Museo Arqueológico Nacional".Anales de Historia del Arte.24.Madrid:Ediciones Complutense:157.ISSN0214-6452.

- ^Martín Moreno, Elena (November 2016)."La transmisión del saber clásico Astrolabio andalusí de Ibn Said"(PDF).

- ^abc"Los reinos cristianos (s. VIII–XV)"(PDF).pp. 82, 85.

- ^Cómez Ramos, Rafael (2006)."Iconología de Pedro I de Castilla"(PDF).Historia. Instituciones. Documentos.33.Seville:Universidad de Sevilla:68–69.

- ^"Oriente Próximo Antiguo"(PDF).p. 109.

- ^Calvo Capilla, Susana (6 September 2005)."La colección de Marius de Zayas (I)".Rinconete.Centro Virtual Cervantes.ISSN1885-5008.

- ^"Museo arqueológico Nacional. Memoria anual 2001"(PDF).p. 12.

- ^"Egypt and the Near East".man.es.Retrieved2022-05-10.

- ^Mellado, Esther Pons (2018)."La colección egipcia de Eduard Toda i Güell del Museo Arqueológico Nacional".Arqueología de los museos. 150 años de la creación del Museo Arqueológico Nacional: Actas del V Congreso Internacional de Historia de la Arqueología / IV Jornadas de Historia SEHA - MAN, 2018, págs. 1075-1090.Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones: 1075–1090.

- ^ab"Museum collections".man.es.Retrieved2022-05-10.

- ^"Greece".man.es.Retrieved2022-05-10.

- ^"Publications - Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport".sede.educacion.gob.es.Retrieved2022-05-10.

External links[edit]

- National Archaeological Museum of Spain - Muselia

- Official list of museums in Spain

- National Archaeological Museum (Madrid)withinGoogle Arts & Culture

Media related toMuseo Arqueológico Nacional de Españaat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toMuseo Arqueológico Nacional de Españaat Wikimedia Commons

![Lioness of Baena [es]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Leona_de_Baena_%2840730657161%29.jpg/292px-Leona_de_Baena_%2840730657161%29.jpg)

![Sundial from Baelo Claudia [es]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_33185_-_Reloj_solar_de_Baelo_Claudia.jpg/148px-Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_33185_-_Reloj_solar_de_Baelo_Claudia.jpg)

![Puteal from La Moncloa [es]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_2691_-_Puteal_de_la_Moncloa_03.jpg/127px-Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_2691_-_Puteal_de_la_Moncloa_03.jpg)

![Paleochristian sarcophagus from Astorga [es]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_50310_-_Sarc%C3%B3fago_de_Astorga.jpg/306px-Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_50310_-_Sarc%C3%B3fago_de_Astorga.jpg)

![Eagle-like fibulae from Alovera [es]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Alovera_M.A.N..JPG/264px-Alovera_M.A.N..JPG)

![The deer of Medina Azahara [es], a bronze fountain](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Cierva_%2840707126722%29.jpg/170px-Cierva_%2840707126722%29.jpg)

![Astrolabe of ibn Said [es], made in 1067 in Toledo by Ibrahim ibn Said al-Sahli[20]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/Astrolabio_%2816787706916%29.jpg/168px-Astrolabio_%2816787706916%29.jpg)

![Arca de las Bienaventuranzas [es]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/ArquetaDeLasBienaventuranzas.jpg/187px-ArquetaDeLasBienaventuranzas.jpg)

![praying statue of Peter I of Castile [es]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/M.A.N._-_Estatua_orante_de_Pedro_I.jpg/91px-M.A.N._-_Estatua_orante_de_Pedro_I.jpg)