Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa | |

|---|---|

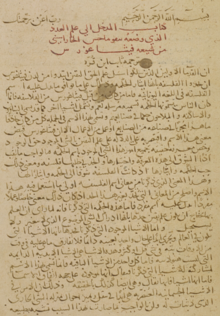

Plato (left) and Nicomachus (right), as inventors of music, from a 12th-century manuscript | |

| Born | c. 60 |

| Died | c. 120 |

| Notable work | Introduction to Arithmetic Manual of Harmonics |

| Era | Ancient Roman philosophy |

| School | Neopythagoreanism |

Main interests | Arithmetic,Music |

Notable ideas | Multiplication tables |

Nicomachus of Gerasa(Greek:Νικόμαχος;c. 60– c. 120 AD) was anAncient GreekNeopythagoreanphilosopher fromGerasa,in theRoman province of Syria(nowJerash,Jordan). Like manyPythagoreans,Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his worksIntroduction to ArithmeticandManual of Harmonics,which are an important resource onAncient Greek mathematicsandAncient Greek musicin theRoman period.Nicomachus' work on arithmetic became a standard text for Neoplatonic education inLate antiquity,with philosophers such asIamblichusandJohn Philoponuswriting commentaries on it. A Latin paraphrase by Boethius of Nicomachus's works on arithmetic and music became standard textbooks in medieval education.

Life

[edit]Little is known about the life of Nicomachus except that he was aPythagoreanwho came fromGerasa.[1]HisManual of Harmonicswas addressed to a lady of noble birth, at whose request Nicomachus wrote the book, which suggests that he was a respected scholar of some status.[2]He mentions his intent to write a more advanced work, and how the journeys he frequently undertakes leave him short of time.[2]The approximate dates in which he lived (c. 100 AD) can only be estimated based on which other authors he refers to in his work, as well as which later mathematicians who refer to him.[1]He mentionsThrasyllusin hisManual of Harmonics,and hisIntroduction to Arithmeticwas apparently translated intoLatinin the mid 2nd century byApuleius,[2]while he makes no mention at all of eitherTheon of Smyrna's work on arithmetic orPtolemy's work on music, implying that they were either later contemporaries or lived in the time after he did.[1]

Philosophy

[edit]Historians consider Nicomachus aNeopythagoreanbased on his tendency to view numbers as havingmysticalproperties rather than their mathematical properties,[3][4]citing an extensive amount of Pythagorean literature in his work, including works byPhilolaus,Archytas,andAndrocydes.[1]He writes extensively onnumbers,especially on the significance ofprime numbersandperfect numbersand argues thatarithmeticis ontologically prior to the other mathematical sciences (music,geometry,andastronomy), and is theircause.Nicomachus distinguishes between the wholly conceptual immaterial number, which he regards as the 'divine number', and the numbers which measure material things, the 'scientific' number.[2]Nicomachus provided one of the earliest Greco-Romanmultiplication tables;the oldest extant Greek multiplication table is found on a wax tablet dated to the 1st century AD (now found in theBritish Museum).[5]

Metaphysics

[edit]Although Nicomachus is considered a Pythagorean,John M. Dillonsays that Nicomachus's philosophy "fits comfortably within the spectrum ofcontemporary Platonism."[6]In his work on arithmetic, Nicomachus quotes fromPlato'sTimaeus[7]to make a distinction between the intelligible world ofFormsand the sensible world, however, he also makes more Pythagorean distinctions, such as betweenOdd and evennumbers.[6]Unlike many other Neopythagoreans, such asModeratus of Gades,Nicomachus makes no attempt to distinguish between theDemiurge,who acts on the material world, andThe Onewhich serves as the supremefirst principle.[6]For Nicomachus,Godas the supreme first principle is both the demiurge and the Intellect (nous), which Nicomachus also equates to being themonad,thepotentialityfrom which all actualities are created.[6]

Works

[edit]Two of Nicomachus' works, theIntroduction to Arithmeticand theManual of Harmonicsare extant in a complete form, and two others, a work onTheology of Arithmeticand aLife of Pythagorassurvive in fragments, epitomes, and summaries by later authors.[1]TheTheology of Arithmetic(Ancient Greek:Θεολογούμενα ἀριθμητικῆς), on the Pythagorean mystical properties of numbers in two books is mentioned by Photius. There is an extant work sometimes attributed to Iamblichus under this title written two centuries later which contains a great deal of material thought to have been copied or paraphrased from Nicomachus' work.Nicomachus'sLife of Pythagoraswas one of the main sources used byPorphyryandIamblichus,for their (extant)Livesof Pythagoras.[1]AnIntroduction to Geometry,referred to by Nicomachus himself in theIntroduction to Arithmetic,[8]has not survived.[1]Among his known lost work is another larger work on music, promised by Nicomachus himself, and apparently[citation needed]referred to byEutociusin his comment on the sphere and cylinder ofArchimedes.

Introduction to Arithmetic

[edit]Introduction to Arithmetic(Greek:Ἀριθμητικὴ εἰσαγωγή,Arithmetike eisagoge) is the only extant work on mathematics by Nicomachus. The work contains both philosophical prose and basic mathematical ideas. Nicomachus refers toPlatoquite often, and writes thatphilosophycan only be possible if one knows enough aboutmathematics.Nicomachus also describes hownatural numbersand basic mathematical ideas are eternal and unchanging, and in anabstractrealm. The work consists of two books, twenty-three and twenty-nine chapters, respectively.

Nicomachus's presentation is much less rigorous thanEuclidcenturies earlier. Propositions are typically stated and illustrated with one example, but not proven through inference. In some instances this results in patently false assertions. For example, he states that from(a-b) ∶ (b-c) ∷ c ∶ ait can be concluded thatab=2bc,only because this is true for a=6, b=5 and c=3.[9]

Boethius'De institutione arithmeticais in large part a Latin translation of this work.

Manual of Harmonics

[edit]Manuale Harmonicum(Ἐγχειρίδιον ἁρμονικῆς,Encheiridion Harmonikes) is the first importantmusic theorytreatise since the time ofAristoxenusandEuclid.It provides the earliest surviving record of the legend ofPythagoras's epiphany outside of a smithy that pitch is determined by numeric ratios. Nicomachus also gives the first in-depth account of the relationship between music and the ordering of the universe via the "music of the spheres."Nicomachus's discussion of the governance of the ear and voice in understanding music unitesAristoxenianand Pythagorean concerns, normally regarded as antitheses.[10]In the midst of theoretical discussions, Nicomachus also describes theinstrumentsof his time, also providing a valuable resource. In addition to theManual,ten extracts survive from what appear to have originally been a more substantial work on music.

Legacy

[edit]

Late antiquity

[edit]TheIntroduction to Arithmeticof Nicomachus was a standard textbook in Neoplatonic schools, and commentaries on it were written byIamblichus(3rd century) andJohn Philoponus(6th century).[1]

TheArithmetic(in Latin:De Institutione Arithmetica) of Boethius was aLatinparaphraseand a partial translation of theIntroduction to Arithmetic.[11]TheManual of Harmonicsalso became the basis of the Boethius' Latin treatise titledDe institutione musica.[12]

Medieval European philosophy

[edit]The work of Boethius on arithmetic and music was a core part of theQuadriviumliberal arts and had a great diffusion during theMiddle Ages.[13]

Nicomachus's theorem

[edit]At the end of Chapter 20 of hisIntroduction to Arithmetic,Nicomachus points out that if one writes a list of the odd numbers, the first is the cube of 1, the sum of the next two is the cube of 2, the sum of the next three is the cube of 3, and so on. He does not go further than this, but from this it follows that the sum of the firstncubes equals the sum of the firstodd numbers, that is, the odd numbers from 1 to.The average of these numbers is obviously,and there areof them, so their sum isMany early mathematicians have studied and provided proofs of Nicomachus's theorem.[14]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^abcdefghDillon 1996,pp. 352–353.

- ^abcdMidonick 1965,pp. 15–16.

- ^Eric Temple Bell (1940),The development of mathematics,page 83.

- ^Frank J. Swetz (2013),The European Mathematical Awakening,page 17, Courier

- ^David E. Smith (1958),History of Mathematics, Volume I: General Survey of the History of Elementary Mathematics,New York: Dover Publications (a reprint of the 1951 publication),ISBN0-486-20429-4,pp 58, 129.

- ^abcdDillon 1996,pp. 353–358.

- ^Plato,Timaeus27D

- ^Nicomachus,Arithmetica,ii. 6. 1.

- ^Heath, Thomas(1921).A History of Greek Mathematics.Vol. 1. pp. 97–98.

- ^Levin, Flora R.(2001)."Nicomachus [Nikomachos] of Gerasa".Grove Music Online.Oxford:Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.19911.ISBN978-1-56159-263-0.Retrieved25 September2021.(subscription orUK public library membershiprequired)

- ^Edward Grant(1974).A Source Book in Medieval Science.Source books in the history of the sciences. Vol. 13. Harvard University Press. p. 17.ISBN9780674823600.ISSN1556-9063.OCLC1066603.

- ^Arnold, Jonathan; Bjornlie, Shane; Sessa, Kristina (April 18, 2016).A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy.Brill's Companions to European History. Brill. p. 332.ISBN9789004315938.OCLC1016025625.RetrievedMay 16,2021.

- ^Ivor Bulmer-Thomas(April 1, 1985)."Boethian Number Theory - Michael Masi: Boethian Number Theory: A Translation of the De Institutione Arithmetica (with Introduction and Notes)".The Classical Review.35(1). The Classical Association,Harvard University Press:86–87.doi:10.1017/S0009840X00107462.S2CID125741349.

- ^Pengelley, David (2002), "The bridge between continuous and discrete via original sources",Study the Masters: The Abel-Fauvel Conference(PDF),National Center for Mathematics Education, Univ. of Gothenburg, Sweden

Bibliography

[edit]Editions and translations

[edit]Introduction to Arithmetic

[edit]- Nicomachus, of Gerasa; Hoche, Richard Gottfried (1866).Nicomachi Geraseni Pythagorei Introductionis arithmeticae libri II(in Ancient Greek). Lipsiae: in aedibvs B.G. Teubneri.Retrieved16 April2023.

- D'Ooge, Martin Luther; Robbins, Frank Egleston; Karpinski, Louis Charles (1926).Nicomachus' Introduction to Arithmetic.Macmillan.Retrieved16 April2023.

Manual of Harmonics

[edit]- Jan, Karl von; Nicomachus (1895).Musici scriptores graeci. Aristoteles, Euclides, Nicomachus, Bacchius, Gaudentius, Alypius et melodiarum veterum quidquid exstat(in Ancient Greek). Lipsiae, in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. pp. 209–282.Retrieved16 April2023.

- Andrew Barker, editor,Greek Musical Writingsvol 2:Harmonic and Acoustic Theory(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), pp. 245–69.

Primary sources

[edit]- Iamblichus (January 1989). Gillian Clark (ed.).On the Pythagorean Life.Liverpool University Press.ISBN9780853233268.

- Photius,Bibliotheca

- Anonymous, Theology of Arithmetic

- Boethius(1488).De institutione arithmetica(in Latin).Erhard Ratdolt.p. 110.Archivedfrom the original on May 16, 2021 – viaInternet Archive.

References

[edit]- Dillon, John M. (1996). "Nicomachus of Gerasa".The Middle Platonists, 80 B.C. to A.D. 220.Cornell University Press. pp. 352–361.ISBN978-0-8014-8316-5.Retrieved16 April2023.

- Midonick, Henrietta O. (1965).The treasury of mathematics: a collection of source material in mathematics edited and presented with introductory biographical and historical sketches.Philosophical Library. pp. 15–16.