Noble savage

In Westernanthropology,philosophy,andliterature,thenoble savageis astock characterwho is uncorrupted by civilization. As such, the noble savage symbolizes the innate goodness and moral superiority of a primitive people living in harmony with Nature.[1]In theheroic dramaof the stageplayThe Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards(1672),John Drydenrepresents thenoble savageas an archetype of Man-as-Creature-of-Nature.[2]

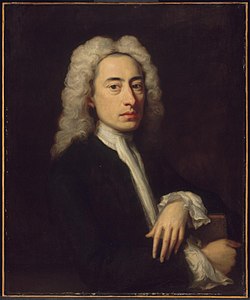

The intellectual politics of theStuart Restoration(1660–1688) expanded Dryden's playwright usage ofsavageto denote a humanwild beastand awild man.[3]Concerning civility and incivility, in theInquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit(1699), the philosopherAnthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury,said that men and women possess an innatemorality,a sense of right and wrong conduct, which is based upon theintellectand the emotions, and not based upon religious doctrine.[4]

In the philosophic debates of 17th-century Britain, theInquiry Concerning Virtue, or Meritwas the Earl of Shaftesbury'sethicalresponse to the political philosophy ofLeviathan(1651), in which Thomas Hobbes defendedabsolute monarchyand justifiedcentralized governmentas necessary because the condition of Man in the apoliticalstate of natureis a "war of all against all", for which reason the lives of men and women are "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" without the political organization of people and resources. The European Hobbes gave, incorrectly, as example theAmerican Indiansas people living in the bellicose state of nature that precedestribesandclansorganizing into the societies that compose a civilization.[4]

In 18th-century anthropology, the termnoble savagethen denotednature's gentleman,an ideal man born from the sentimentalism ofmoral sense theory.In the 19th century, in the essay "The Noble Savage" (1853) Charles Dickens rendered the noble savage into a rhetoricaloxymoronby satirizing the BritishromanticisationofPrimitivismin philosophy and in the arts made possible by moral sentimentalism.[5]

In many ways, the noble savage notion entails fantasies about the non-West that cut to the core of the conversation in the social sciences about Orientalism, colonialism and exoticism. The key question that emerges here is whether an admiration of "the Other" as noble undermines or reproduces the dominant hierarchy, whereby the Other is subjugated by Western powers.[6]

Origins[edit]

- 16th century

Thestock characterof thenoble savageoriginated from the essay "Of Cannibals"(1580), about theTupinambá peopleof Brazil, wherein the philosopherMichel de Montaignepresents "Nature's Gentleman", thebon sauvagecounterpart to civilized Europeans in the 16th century.

- 17th century

The first usage of the termnoble savageinEnglish literatureoccurs in John Dryden's stageplayThe Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards(1672), about the troubled love of the hero Almanzor and the Moorish beauty Almahide, in which the protagonist defends his life as a free man by denying a prince's right to put him to death, because he is not a subject of the prince:

I am as free as nature first made man,

Ere the base laws of servitude began,

When wild in woods the noble savage ran.[7]

- 18th century

By the 18th century, Montaigne's predecessor to the noble savage,nature's gentlemanwas a stock character usual to thesentimental literatureof the time, for which a type of non-European Other became a background character for European stories about adventurous Europeans in the strange lands beyond continental Europe. For the novels, the opera, and the stageplays, the stock of characters included the "Virtuous Milkmaid" and the "Servant-More-Clever-Than-the-Master" (e.g.Sancho PanzaandFigaro), literary characters who personify the moral superiority of working-class people in the fictional world of the story.

In English literature,British North Americawas the geographiclocus classicusfor adventure and exploration stories about European encounters with the noble savage natives, such as the historical novelThe Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757(1826), byJames Fenimore Cooper,and the epic poemThe Song of Hiawatha(1855), byHenry Wadsworth Longfellow,both literary works presented theprimitivism(geographic, cultural, political) of North America as an ideal place for the European man to commune with Nature, far from the artifice of civilisation; yet in the poem “An Essay on Man”(1734), the EnglishmanAlexander Popeportrays the American Indian thus:

Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor'd mind

Sees God in clouds, or hears Him in the wind;

His soul proud Science never taught to stray

Far as the solar walk or milky way;

Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv'n,

Behind the cloud-topp'd hill, a humbler heav'n;

Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd,

Some happier island in the wat'ry waste,

Where slaves once more their native land behold,

No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold!

To be, contents his natural desire;

He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire:

But thinks, admitted to that equal sky,

His faithful dog shall bear him company.

To the English intellectual Pope, theAmerican Indianwas an abstractbeingunlike his insular European self; thus, from the Western perspective of "An Essay on Man", Pope's metaphoric usage ofpoormeans "uneducated and a heathen", but also denotes a savage who is happy with his rustic life in harmony with Nature, and who believes indeism,a form ofnatural religion— theidealization and devaluationof the non-European Other derived from the mirror logic of the Enlightenment belief that "men, everywhere and in all times, are the same".

- 19th century

Like Dryden'snoble savageterm, Pope's phrase "Lo, the Poor Indian!" was used to dehumanize the natives of North America for European purposes, and so justified white settlers' conflicts with the local Indians for possession of the land. In the mid-19th century, the journalist-editorHorace Greeleypublished the essay "Lo! The Poor Indian!" (1859), about the social condition of the American Indian in the modern United States:

I have learned to appreciate better than hitherto, and to make more allowance for the dislike, aversion, contempt wherewith Indians are usually regarded by their white neighbors, and have been since the days of the Puritans. It needs but little familiarity with the actual, palpable aborigines to convince anyone that the poetic Indian — the Indian ofCooperandLongfellow— is only visible to the poet's eye. To the prosaic observer, the average Indian of the woods and prairies is a being who does little credit to human nature — a slave of appetite and sloth, never emancipated from the tyranny of one animal passion, save by the more ravenous demands of another.

As I passed over those magnificent bottoms of the Kansas, which form the reservations of theDelawares,Potawatamies,etc., constituting the very best corn-lands on Earth, and saw their owners sitting around the doors of their lodges at the height of the planting season, and in as good, bright planting weather as sun and soil ever made, I could not help saying: "These people must die out — there is no help for them. God has given this earth to those who will subdue and cultivate it, and it is vain to struggle against His righteous decree."[8]

Moreover, during theAmerican Indian Wars(1609–1924) for possession of the land, European white settlers considered the Indians "an inferior breed of men" and mocked them by using the terms "Lo" and "Mr. Lo" as disrespectful forms of address. In the Western U.S., those terms of address also referred to East Coast humanitarians whose noble-savage conception of the American Indian was unlike the warrior who confronted and fought the frontiersman. Concerning the story of the settler Thomas Alderdice, whose wife was captured and killed byCheyenne Indians,The Leavenworth, Kansas, Times and Conservativenewspaper said: "We wish some philanthropists, who talk about civilizing the Indians, could have heard this unfortunate and almost broken-hearted man tell his story. We think [that the philanthropists] would at least have wavered a little in their [high] opinion of the Lo family."[9]

Cultural stereotype[edit]

The Roman Empire[edit]

In Western literature, the Roman bookDe origine et situ Germanorum(On the Origin and Situation of the Germans,AD 98), by the historianPublius Cornelius Tacitus,introduced the anthropologic concept of thenoble savageto the Western World; later acultural stereotypewho featured in the exotic-place tourism reported in the Europeantravel literatureof the 17th and the 18th centuries.[10]

Al-Andalus[edit]

The 12th-centuryAndalusiannovelThe Living Son of the Vigilant(Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān,1160), by the polymathIbn Tufail,explores the subject ofnatural theologyas a means to understand the material world. The protagonist is awild manisolated from his society, whose trials and tribulations lead him to knowledge of Allah by living a rustic life in harmony with Mother Nature.[11]

Kingdom of Spain[edit]

In the 15th century, soon afterarriving to the Americasin 1492, the Europeans employed the termsavageto dehumanise theindigènes(noble-savage natives) of the newly discovered "New World"as ideological justification for theEuropean colonization of the Americas,called the Age of Discovery (1492–1800); thus with thedehumanizingstereotypes of thenoble savageand theindigène,thesavageand thewild manthe Europeans granted themselves the right to colonize the natives inhabiting the islands and the continental lands of the northern, the central, and the southern Americas.[12]

Theconquistadormistreatment of the indigenous peoples of theViceroyalty of New Spain(1521–1821) eventually produced bad-conscience recriminations amongst the European intelligentsias for and against colonialism.[13]As the Roman Catholic Bishop ofChiapas,the priestBartolomé de las Casaswitnessed the enslavement of theindigènesof New Spain, yet idealized them into morally innocent noble savages living a simple life in harmony with Mother Nature. At theValladolid debate(1550–1551) of the moral philosophy of enslaving the native peoples of the Spanish colonies, Bishop de las Casas reported the noble-savage culture of the natives, especially noting their plain-mannersocial etiquetteand that they did not have the social custom of telling lies.

Kingdom of France[edit]

In the intellectual debates of the late 16th and 17th centuries, philosophers used the racist stereotypes of thesavageand thegood savageas moral reproaches of the European monarchies fighting theThirty Years' War(1618–1648) and theFrench Wars of Religion(1562–1598). In the essay "Of Cannibals"(1580), Michel de Montaigne reported that theTupinambá peopleof Brazil ceremoniously eat the bodies of their dead enemies, as a matter of honour, whilst reminding the European reader that suchwild manbehavior was analogous to the religious barbarism ofburning at the stake:"One calls ‘barbarism’ whatever he is not accustomed to."[14]The academicTerence Cavefurther explains Montaigne's point ofmoral philosophy:

The cannibal practices are admitted [by Montaigne] but presented as part of a complex and balanced set of customs and beliefs which "make sense" in their own right. They are attached to a powerfully positive morality of valor and pride, one that would have been likely to appeal to early modern codes of honor, and they are contrasted with modes of behavior in the France of the wars of religion, which appear as distinctly less attractive, such astortureand barbarous methods of execution.[15]

As philosophic reportage, "Of Cannibals" appliescultural relativismto compare the civilized European to the uncivilized noble savage. Montaigne's anthropological report aboutcannibalismin Brazil indicated that the Tupinambá people were neither a noble nor an exceptionally goodfolk,yet neither were the Tupinambá culturally or morally inferior to his contemporary, 16th-century European civilization. From the perspective ofClassical liberalismof Montaigne's humanist portrayal of thecustomsof honor of the Tupinambá people indicatesWestern philosophicrecognition that people are people, despite their different customs, traditions, and codes of honor. The academic David El Kenz explicates Montaigne's background concerning the violence of customary morality:

In hisEssais...Montaigne discussed the first three wars of religion (1562–63; 1567–68; 1568–70) quite specifically; he had personally participated in [the wars], on the side of the [French] royal army, in southwestern France. The [anti-Protestant]St. Bartholomew's Day massacre[1572] led him to retire to his lands in the Périgord region, and remain silent on all public affairs until the 1580s. Thus, it seems that he was traumatized by the massacre. To him, cruelty was a criterion that differentiated the Wars of Religion [1562–1598] from previous conflicts, which he idealized. Montaigne considered that three factors accounted for the shift from regular war to the carnage of civil war: popular intervention, religious demagogy, and the never-ending aspect of the conflict....

He chose to depict cruelty through the image of hunting, which fitted with the tradition of condemning hunting for its association with blood and death, but it was still quite surprising, to the extent that this practice was part of thearistocraticway of life. Montaigne reviled hunting by describing it as an urban massacre scene. In addition, the man–animal relationship allowed him to definevirtue,which he presented as the opposite of cruelty....[As] a sort of natural benevolence based on...personal feelings.

Montaigne associated the [human] propensity to cruelty toward animals, with that exercised toward men. After all, following the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, the invented image of Charles IX shooting Huguenots from theLouvre Palacewindow did combine the established reputation of the King as a hunter, with a stigmatization of hunting, a cruel and perverted custom, did it not?[16]

Literature[edit]

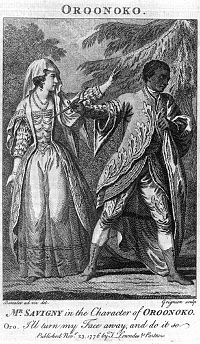

The themes about the person andpersonaof the noble savage are the subjects of the novelOroonoko: Or the Royal Slave(1688), byAphra Behn,which is the tragic love story between Oroonoko and the beautiful Imoinda, an African king and queen respectively. AtCoramantien,Ghana, the protagonist is deceived and delivered into theAtlantic slave trade(16th–19th centuries), and Oroonoko becomes a slave ofplantation colonistsinSurinam(Dutch Guiana, 1667–1954). In the course of his enslavement, Oroonoko meets the woman who narrates to the reader the life and love of Prince Oroonoko, his enslavement, his leading aslave rebellionagainst the Dutch planters of Surinam, and his consequent execution by the Dutch colonialists.[17]

Despite Behn having written thepopular novelfor money,Oroonokoproved to be political-protest literature againstslavery,because the story, plot, and characters followed thenarrative conventionsof the Europeanromance novel.In the event, the Irish playwrightThomas Southerneadapted the novelOroonokointo thestage playOroonoko: A Tragedy(1696) that stressed thepathosof the love story, the circumstances, and the characters, which consequently gave political importance to the play and the novel for the candidcultural representationof slave-powered European colonialism.

Uses of the stereotype[edit]

Romantic primitivism[edit]

In the 1st century AD, in the bookGermania,Tacitus ascribed to the Germans the cultural superiority of thenoble savageway of life, because Rome was too civilized, unlike the savage Germans.[18]The art historianErwin Panofskyexplains that:

There had been, from the beginning of Classical speculation, two contrasting opinions about thenatural state of man,each of them, of course, a "Gegen-Konstruktion" to the conditions under which it was formed. One view, termed "soft" primitivism in an illuminating book by Lovejoy and Boas, conceives of primitive life as a golden age of plenty, innocence, and happiness — in other words, as civilized life purged of its vices. The other, "hard" form of primitivism conceives of primitive life as an almost subhuman existence full of terrible hardships and devoid of all comforts — in other words, as civilized life stripped of its virtues.[19]

— Et in Arcadia Ego: Poussin and the Elegiac Tradition (1936)

In the novelThe Adventures of Telemachus, Son of Ulysses(1699), in the “Encounter with the Mandurians” (Chapter IX), the theologianFrançois Fénelonpresented thenoble savagestock character in conversation with civilized men from Europe about possession and ownership ofNature:

On our arrival upon this coast we found there a savage race who...lived by hunting and by the fruits which the trees spontaneously produced. These people...were greatly surprised and alarmed by the sight of our ships and arms and retired to the mountains. But since our soldiers were curious to see the country and hunt deer, they were met by some of these savage fugitives.

The leaders of the savages accosted them thus: “We abandoned for you, the pleasant sea-coast, so that we have nothing left, but these almost inaccessible mountains: at least, it is just that you leave us in peace and liberty. Go, and never forget that you owe your lives to our feeling of humanity. Never forget that it was from a people whom you call rude and savage that you receive this lesson in gentleness and generosity....We abhor that brutality which, under the gaudy names of ambition and glory,...sheds the blood of men who are all brothers....We value health, frugality, liberty, and vigor of body and mind: the love of virtue, the fear of the gods, a natural goodness toward our neighbors, attachment to our friends, fidelity to all the world, moderation in prosperity, fortitude in adversity, courage always bold to speak the truth, and abhorrence of flattery....

If the offended gods so far blind you as to make you reject peace, you will find, when it is too late, that the people who are moderate and lovers of peace are the most formidable in war.”

— Encounter with the Mandurians,The Adventures of Telemachus, Son of Ulysses(1699)[20]

In the 18th century, British intellectual debate about Primitivism used the Highland Scots as a local, European example of anoble savagepeople, as often as the American Indians were the example. The English cultural perspective scorned the ostensibly rudemannersof the Highlanders, whilst admiring and idealizing the toughness of person and character of the Highland Scots; the writerTobias Smollettdescribed the Highlanders:

They greatly excel the Lowlanders in all the exercises that require agility; they are incredibly abstemious, and patient of hunger and fatigue; so steeled against the weather, that in traveling, even when the ground is covered with snow, they never look for a house, or any other shelter but their plaid, in which they wrap themselves up, and go to sleep under the cope of heaven. Such people, in quality of soldiers, must be invincible....

— The Expedition of Humphry Clinker(1771)[21]

Thomas Hobbes[edit]

The imperial politics of Western Europe featured debates aboutsoft primitivismandhard primitivismworsened with the publication ofLeviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil(1651), byThomas Hobbes,which justified the central-government regime ofabsolute monarchyas politically necessary for societal stability and the national security of the state:

Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of War, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall. In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

— Leviathan[22]

In the Kingdom of France, critics of the Crown and Church risked censorship and summary imprisonment without trial, and primitivism was political protest against the repressive imperial règimes ofLouis XIVandLouis XV.In his travelogue of North America, the writerLouis-Armand de Lom d'Arce de Lahontan, Baron de Lahontan,who had lived with the Huron Indians (Wyandot people), ascribeddeistandegalitarianpolitics to Adario, a Canadian Indian who played the role of noble savage for French explorers:

Adario sings the praises ofNatural Religion....As against society, he puts forward a sort ofprimitive Communism,of which the certain fruits are Justice and a happy life....[The Savage] looks with compassion on poor civilized man — no courage, no strength, incapable of providing himself with food and shelter: a degenerate, a moralcretin,a figure of fun in his blue coat, his red hose, his black hat, his white plume and his green ribands. He never really lives, because he is always torturing the life out of himself to clutch at wealth and honors, which, even if he wins them, will prove to be but glittering illusions....For science and the arts are but the parents of corruption. The Savage obeys the will of Nature, his kindly mother, therefore he is happy. It is civilized folk who are the real barbarians.

— Paul Hazard,The European Mind[23]

Interest in the remote peoples of the Earth, in the unfamiliar civilizations of the East, in the untutored races of America and Africa, was vivid in France in the 18th century. Everyone knows howVoltaireandMontesquieuused Hurons or Persians to hold up the [looking] glass to Western manners and morals, as Tacitus used the Germans to criticize the society of Rome. But very few ever look into the seven volumes of theAbbé Raynal'sHistory of the Two Indies,which appeared in 1772. It is however one of the most remarkable books of the century. Its immediate practical importance lay in the array of facts which it furnished to the friends of humanity in the movement againstnegro slavery.But it was also an effective attack on the Church and the sacerdotal system....Raynal brought home to the conscience of Europeans the miseries which had befallen the natives of the New World through the Christian conquerors and their priests. He was not indeed an enthusiastic preacher of Progress. He was unable to decide between the comparative advantages of thesavage state of natureand the most highly cultivated society. But he observes that "the human race is what we wish to make it", that the felicity of Man depends entirely on the improvement of legislation, and...his view is generally optimistic.

— J.B. Bury,The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth[24]

Benjamin Franklin[edit]

Benjamin Franklin was critical of government indifference to thePaxton Boysmassacre of theSusquehannockinLancaster County, Pennsylvaniain December 1763. Within weeks of the murders, he publishedA Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County,in which he referred to the Paxton Boys as "Christian white savages" and called for judicial punishment of those who carried the Bible in one hand and a hatchet in the other.[25]

When the Paxton Boys led an armed march onPhiladelphiain February 1764, with the intent of killing theMoravianLenapeandMohicanwho had been given shelter there, Franklin recruitedassociatorsincludingQuakersto defend the city and led a delegation that met with the Paxton leaders atGermantownoutside Philadelphia. The marchers dispersed after Franklin convinced them to submit their grievances in writing to the government.[26]

In his 1784 pamphletRemarks Concerning the Savages of North America,Franklin especially noted the racism inherent to the colonists using the wordsavageas a synonym for indigenous people:

"Savages" we call them, because their manners differ from ours, which we think the perfection of civility; they think the same of theirs.[27]

Franklin praised the way of life of indigenous people, their customs of hospitality, their councils of government, and acknowledged that while some Europeans had foregone civilization to live like a "savage", the opposite rarely occurred, because few indigenous people chose "civilization" over "savagery".[28]

Jean-Jacques Rousseau[edit]

Like the Earl of Shaftesbury in theInquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit(1699),Jean-Jacques Rousseaulikewise believed that Man is innately good, and that urban civilization, characterized by jealousy, envy, and self-consciousness, has made men bad in character. InDiscourse on the Origins of Inequality Among Men(1754), Rousseau said that in the primordialstate of nature,man was a solitary creature who was notméchant(bad), but was possessed of an "innate repugnance to see others of his kind suffer."[29]

Moreover, as thephilosopheof theJacobin radicalsof the French Revolution (1789–1799), ideologues accused Rousseau of claiming that thenoble savagewas a real type of man, despite the term not appearing in work written by Rousseau;[30]in addressingThe Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality(1923), the academic Arthur O. Lovejoy said that:

The notion that Rousseau’sDiscourse on Inequalitywas essentially a glorification of the State of Nature, and that its influence tended to wholly or chiefly to promote “Primitivism” is one of the most persistent historical errors.[31]

In theDiscourse on the Origins of Inequality,Rousseau said that the rise of humanity began a "formidable struggle for existence" between the species man and the other animal species of Nature.[32]That under the pressure of survival emergedle caractère spécifique de l'espèce humaine,the specific quality of character, which distinguishes man from beast, such asintelligencecapable of "almost unlimited development", and thefaculté de se perfectionner,the capability of perfecting himself.[33]

Having invented tools, discovered fire, and transcended the state of nature, Rousseau said that "it is easy to see.... that all our labors are directed upon two objects only, namely, for oneself, the commodities of life, and consideration on the part of others"; thusamour propre(self-regard) is a "factitious feeling arising, only in society, which leads a man to think more highly of himself than of any other." Therefore, "it is this desire for reputation, honors, and preferment which devours us all... this rage to be distinguished, that we own what is best and worst in men — our virtues and our vices, our sciences and our errors, our conquerors and our philosophers — in short, a vast number of evil things and a small number of good [things]"; that is the aspect of character "which inspires men to all the evils which they inflict upon one another."[34]

Men become men only in a civil society based upon law, and only a reformed system of education can make men good; the academic Lovejoy explains that:

For Rousseau, man's good lay in departing from his "natural" state — but not too much; "perfectability", up to a certain point, was desirable, though beyond that point an evil. Not its infancy but itsjeunesse[youth] was the best age of the human race. The distinction may seem to us slight enough; but in the mid-eighteenth century it amounted to an abandonment of the stronghold of theprimitivisticposition. Nor was this the whole of the difference. As compared with the then-conventional pictures of the savage state, Rousseau's account, even of this third stage, is far less idyllic; and it is so because of his fundamentally unfavorable view of human naturequâhuman....[Rousseau's] savages are quite unlike Dryden's Indians: "Guiltless men, that danced away their time, / Fresh as the groves and happy as their clime" or Mrs.Aphra Behn's natives ofSurinam,who represented an absolute idea of the first state of innocence "before men knew how to sin." The men in Rousseau's "nascent society" already had 'bien des querelles et des combats "[many quarrels and fights];l'amour proprewas already manifest in them...and slights or affronts were consequently visited withvengeances terribles.[35]

Rousseau proposes reorganizing society with asocial contractthat will "draw from the very evil from which we suffer the remedy which shall cure it"; Lovejoy notes that in theDiscourse on the Origins of Inequality,Rousseau:

declares that there is a dual process going on through history; on the one hand, an indefinite progress in all those powers and achievements which express merely the potency of man'sintellect;on the other hand, an increasing estrangement of men from one another, an intensification of ill-will and mutual fear, culminating in a monstrous epoch of universal conflict and mutual destruction. And the chief cause of the latter process Rousseau, following Hobbes and [Bernard]Mandeville,found, as we have seen, in that unique passion of the self-conscious animal — pride, self esteem,le besoin de se mettre au dessus des autres[the need to put oneself above others]. A large survey of history does not belie these generalizations, and the history of the period since Rousseau wrote lends them a melancholy verisimilitude. Precisely the two processes, which he described have...been going on upon a scale beyond all precedent: immense progress in man's knowledge and in his powers over nature, and, at the same time, a steady increase of rivalries, distrust, hatred and, at last, "the most horrible state of war"...[Moreover, Rousseau] failed to realize fully how stronglyamour propretended to assume a collective form...in pride ofrace,ofnationality,ofclass.[36]

Charles Dickens[edit]

In 1853, in the weekly magazineHousehold Words,Charles Dickens published a negative review of the Indian Gallery cultural program, by the portraitistGeorge Catlin,which then was touring England. About Catlin's oil paintings of the North American natives, the poet and criticCharles Baudelairesaid that "He [Catlin] has brought back alive the proud and free characters of these chiefs; both theirnobilityand manliness. "[37]

Despite European idealization of the noble savage as a type of morally superior man, in the essay “The Noble Savage” (1853), Dickens expressed repugnance for the American Indians and their way of life, because they were dirty and cruel and continually quarrelled among themselves.[38]In the satire ofromanticised primitivismDickens showed that the painter Catlin, the Indian Gallery of portraits and landscapes, and the white people who admire the idealized American Indians or thebushmenof Africa are examples of the termnoble savageused as a means ofOtheringa person into aracialist stereotype.[39]Dickens begins by dismissing the noble savage as not being a distinct human being:

To come to the point at once, I beg to say that I have not the least belief in the Noble Savage. I consider him a prodigious nuisance and an enormous superstition....[40]

I don't care what he calls me. I call him a savage, and I call a savage a something highly desirable to be civilized off the face of the Earth....[41]

The noble savage sets a king to reign over him, to whom he submits his life and limbs without a murmur or question, and whose whole life is passed chin deep in a lake of blood; but who, after killing incessantly, is in his turn killed by his relations and friends the moment a grey hair appears on his head. All the noble savage's wars with his fellow-savages (and he takes no pleasure in anything else) are wars of extermination — which is the best thing I know of him, and the most comfortable to my mind when I look at him. He has no moral feelings of any kind, sort, or description; and his "mission" may be summed up as simply diabolical.[42]

Dickens ends his cultural criticism by reiterating his argument against the romanticizedpersonaof the noble savage:

To conclude as I began. My position is that if we have anything to learn from the Noble Savage it is what to avoid. His virtues are a fable; his happiness is a delusion; his nobility, nonsense. We have no greater justification for being cruel to the miserable object, than for being cruel to a WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE or an ISAAC NEWTON; but he passes away before an immeasurably better and higher power than ever ran wild in any earthly woods, and the world will be all the better when this place [Earth] knows him no more.[43]

Theories of racialism[edit]

In 1860, the physicianJohn Crawfurdand the anthropologistJames Huntidentified the racial stereotype ofthe noble savageas an example ofscientific racism,[44]yet, as advocates ofpolygenism— that eachraceis a distinct species of Man — Crawfurd and Hunt dismissed the arguments of their opponents by accusing them of being proponents of "Rousseau's Noble Savage". Later in his career, Crawfurd re-introduced thenoble savageterm to modernanthropologyand deliberately ascribed coinage of the term to Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[45]

Modern perspectives[edit]

Supporters of primitivism[edit]

In "The Prehistory of Warfare: Misled by Ethnography" (2006), the researchers Jonathan Haas and Matthew Piscitelli challenged the idea that the human species is innately bellicose and that warfare is an occasional activity by a society, but is not an inherent part of human culture.[46]Moreover, theUNESCO'sSeville Statement on Violence(1986) specifically rejects claims that the human propensity towards violence has a genetic basis.[47][48]

Anarcho-primitivists,such as the philosopherJohn Zerzan,rely upon a strongethical dualismbetween Anarcho-primitivism andcivilization;hence, "life before domestication [and] agriculture was, in fact, largely one of leisure, intimacy with nature, sensual wisdom, sexual equality, and health."[49]Zerzan's claims about the moral superiority of primitive societies are based on a certain reading of the works of anthropologists, such asMarshall SahlinsandRichard Borshay Lee,wherein the anthropologic category ofprimitive societyis restricted to hunter-gatherer societies who have no domesticated animals or agriculture, e.g. the stablesocial hierarchyof the American Indians of the north-west North America, who live from fishing and foraging, is attributed to having domesticated dogs and the cultivation of tobacco, that animal husbandry and agriculture equal civilization.[49][50]

In anthropology, the argument has been made that key tenets of the noble-savage idea inform cultural investments in places seemingly removed from the Tropics, such as the Mediterranean and specifically Greece, during the debt crisis by European institutions (such as documenta) and by various commentators who found Greece to be a positive inspiration for resistance to austerity policies and the neoliberalism of the EU[51] These commentators' positive embrace of the periphery (their noble-savage ideal) is the other side of the mainstream views, also dominant during that period, that stereotyped Greece and the South as lazy and corrupt.

Opponents of primitivism[edit]

InWar Before Civilization: the Myth of the Peaceful Savage(1996), the archaeologistLawrence H. Keeleysaid that the "widespread myth" that "civilized humans have fallen from grace from a simple, primeval happiness, a peacefulgolden age"is contradicted and refuted by archeologic evidence that indicates that violence was common practice in early human societies. That thenoble savageparadigm has warped anthropological literature to political ends.[52]Moreover, the anthropologistRoger Sandalllikewise accused anthropologists of exalting the noble savage above civilized man,[53]by way ofdesigner tribalism,a form ofromanticisedprimitivism that dehumanises Indigenous peoples into the cultural stereotype of theindigènepeoples who live a primitive way of life demarcated and limited bytradition,which discouraged Indigenous peoples fromcultural assimilationinto the dominant Western culture.[54][55][56]

See also[edit]

|

Concepts: |

Cultural examples:

|

References[edit]

Informational notes

Citations

- ^"The noble savage",Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary TheoryThird Edition (1991) J.A. Cudon, Ed. pp. 588–589.

- ^Miner, Earl (1972), "The Wild Man Through the Looking Glass", in Dudley, Edward; Novak, Maximillian E (eds.),The Wild Man Within: An Image in Western Thought from the Renaissance to Romanticism,University of Pittsburgh Press, p. 106,ISBN9780822975991

- ^OED s.v. "savage" B.3.a.

- ^abHarrison, Ross.Locke, Hobbes, and Confusion's Masterpiece(Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 70.

- ^Moore, Grace "Reappraising Dickens's 'Noble Savage'",The Dickensian98:458 (2002): 236–243.

- ^Kalantzis, Konstantinos."The Indigenous Sublime Rethinking Orientalism and Desire from documenta 14 to Highland Crete".Current Anthropology.doi:10.1086/728171.

- ^Noble savage,The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary TheoryThird Edition (1991) J.A. Cuddon, Ed. pp.588–589.

- ^An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859(1860), by Horace Greeley."An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859," Lo! The Poor Indian! ", by Horace Greeley".

- ^Barnett, Louise, inTouched by Fire: the Life, Death, and Mythic Afterlife of George Armstrong Custer(University of Nebraska Press [1986], 2006), pp. 107–108.

- ^Paradies auf Erden?: Mythenbildung als Form von Fremdwahrnehmung: der Südsee-Mythos in Schlüsselphasen der deutschen Literatur(2008) Anja Hall Königshausen & Neumann, p. 0000.

- ^Attar, Samar,The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl's Influence on Modern Western Thought(1989), Le xing ton Books,ISBN0-7391-1989-3.

- ^Borsboom, Ad.The Savage in European Social Thought: A Prelude to the Conceptualization of the Divergent Peoples and Cultures of Australia and Oceania(1988) KILTV, p. 419.

- ^Anthony Pagden,The Fall of the Natural Man: the American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology. Cambridge Iberian and Latin American Studies.(Cambridge University Press, 1982)

- ^Essay "Of Cannibals"

- ^Cave, Terence.How to Read Montaigne(London: Granta Books, 2007), pp. 81–82.

- ^El Kenz, David.Massacres During the Wars of Religion(2007)David El Kenz, "Massacres During the Wars of Religion", 2007

- ^Benítez-Rojo, Antonio (2018). "The Caribbean: From a Sea Basin to an Atlantic Network".The Southern Quarterly.55:196–206.

- ^Lovejoy, A. O. and Boas, G.Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity,Baltimore, I, 1935. pp. 0000.

- ^Erwin Panofsky, "Et in Arcadia Ego", inMeaning in the Visual Arts(New York: Doubleday, 1955).

- ^François de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon, Encounter with the Mandurians, in Chapter IX ofTelemachus, Son of Ulysses,Patrick Riley, translator (Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 130–131; Riley's translation is based on the translation by Tobias Smollett, 1776 (op. cit. p. xvii).

- ^Smollett, Tobias,The Expedition of Humphry Clinker(1771) London: Penguin Books, 1967, p. 292.

- ^Leviathan

- ^See Paul Hazard,The European Mind (1680–1715)([1937], 1969), pp. 13–14, and passim.

- ^J.B. Bury (2008).The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth(second ed.). New York: Cosimo Press. p. 111.

- ^"A Narrative of the Late Massacres".Founders Online.National Archives.Retrieved3 July2023.

- ^Kenny, Kevin (2009).Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn's Holy Experiment.New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN9780199753949.

- ^"Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America".Founders Online.National Archives.Retrieved3 July2023.

- ^Johansen, Bruce E.(1982)."Chapter 5: The Philosopher as Savage".Forgotten Founders: Benjamin Franklin, the Iroquois, and the Rationale for the American Revolution.Ipswich, Massachusetts: Gambit, Inc.ISBN9780876451113.

- ^Lovejoy (1923, 1948) p. 21.

- ^Ellingson, Ter. (2001).

- ^Lovejoy, A.O.The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality(1923) inModern Philology,Vol. 21, No. 2 (Nov. 1923):165–186, Lovejoy's essay was reprinted inEssays in the History of Ideas.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, [1948, 1955, and 1960], atJSTOR.

- ^(Lovejoy (1960), p. 23)

- ^Lovejoy (1960), p. 24.

- ^Rousseau,Discourse on the Origins of Inequalityquoted in Lovejoy (1960), p. 27.

- ^See Lovejoy (1960), p. 31.

- ^Lovejoy (1960), p. 36.

- ^Eisler,The Red Man's Bones(0000), p. 326.

- ^"The Noble Savage"

- ^Moore, "Reappraising Dickens's 'Noble Savage'" (2002): 236–243.

- ^Dickens, Charles. "The Noble Savage" (1853) p. 000.

- ^Dickens, Charles. "The Noble Savage" (1853) p. 000.

- ^Dickens, Charles. "The Noble Savage" (1853) p. 000.

- ^Dickens, Charles. "The Noble Savage" (1853) p. 000.

- ^Ellingson (2001), pp. 249–323.

- ^Douglas, Bronwen; Ballard, Chris, eds. (October 2008).John Crawfurd – 'two separate races'.Epress.anu.edu.au.doi:10.22459/FB.11.2008.ISBN9781921536007.Retrieved2009-02-23.

- ^See:Haas, Jonathan; Piscitelli, Matthew (2013). "The Prehistory of Warfare: Misled by Ethnography". In Fry, Douglas P. (ed.).War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views.New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 168–190.ISBN978-0190232467.

- ^Johnson, Eric Michael (19 June 2012)."The Better Bonobos of Our Nature".Scientific American.Retrieved22 June2021.

- ^Baldwin, Melinda (16 June 2019)."The Search for What Makes Us Human: The Killer Ape Account of the Mid-20th Century".Los Angeles Review of Books.Retrieved22 June2021.

- ^ab"John Zerzan – Future Primitive".Primitivism. Archived fromthe originalon 2 April 2009.Retrieved13 November2011.

- ^"John Zerzan – Running on Emptiness: The Failure of Symbolic Thought".Primitivism. Archived fromthe originalon 31 January 2009.Retrieved13 November2011.

- ^Kalantzis, Konstantinos."The Indigenous Sublime Rethinking Orientalism and Desire from documenta 14 to Highland Crete".Current Anthropology.doi:10.1086/728171.

- ^Keely, Lawrence H.War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage(Oxford, University Press, 1996), p. 5.

- ^See: Patrick Wolfe's opinion of Roger Sandall inThe Anthropological Book Review,September 2001.

- ^Hirsi Ali, Ayaan (12 June 2010) “Facing up to radical Islam”,The Gazettemagazine, Montreal, Canada. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^Peacock, Janice (2006) “Culture Cult Clan 2001: Comments on the Survival of Torres Strait Culture”,Aboriginal History30:138–155. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^Malcolm, Ian (2002).Coming to Terms with Diversity: Educational Responses to Linguistic Plurality in Australia(PDF). Zeitschrift für Australienstudien. 16: 17–30. doi:10.35515/zfa/asj.16/2002.04. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

Further reading

- Barnett, Louise.Touched by Fire: the Life, Death, and Mythic Afterlife of George Armstrong Custer.University of Nebraska Press [1986], 2006.

- Barzun, Jacques(2000).From Dawn to Decadence:500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 to the Present.New York: HarperCollins. pp. 282–294, and passim.

- Bataille, Gretchen, M. and Silet Charles L., editors. Introduction by Vine Deloria, Jr.The Pretend Indian: Images of Native Americans in the Movies.Iowa State University Press, 1980*Berkhofer, Robert F."The White Man's Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present"

- Boas, George ([1933] 1966).The Happy Beast in French Thought in the Seventeenth Century.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Press in 1966.

- Boas, George ([1948] 1997).Primitivism and Related Ideas in the Middle Ages.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. "Killing the White Man's Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century"

- Bury, J.B.(1920).The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth.(Reprint) New York: Cosimo Press, 2008.

- Edgerton, Robert (1992).Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony.New York: Free Press.ISBN978-0-02-908925-5

- Edwards, Brendan Frederick R. (2008)"'He Scarcely Resembles the Real Man': images of the Indian in popular culture".Website:Our Legacy.Material relating to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, found in Saskatchewan cultural and heritage collections.

- Ellingson, Ter. (2001).The Myth of the Noble Savage(Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press).

- Fabian, Johannes.Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object

- Fairchild, Hoxie Neale (1928).The Noble Savage: A Study in Romantic Naturalism(New York)

- Fitzgerald, Margaret Mary ([1947] 1976).First Follow Nature: Primitivism in English Poetry 1725–1750.New York: Kings Crown Press. Reprinted New York: Octagon Press.

- Fryd, Vivien Green (1995). "Rereading the Indian in Benjamin West's" Death of General Wolfe "".American Art.9(1).University of Chicago Press:72–85.doi:10.1086/424234.ISSN1549-6503.JSTOR3109196.S2CID162205173.

- Hazard, Paul([1937] 1947).The European Mind (1690–1715).Cleveland, Ohio: Meridian Books.

- Keeley, Lawrence H. (1996)War Before Civilization:The Myth of the Peaceful Savage.Oxford: University Press.

- Krech, Shepard (2000).The Ecological Indian: Myth and History.New York: Norton.ISBN978-0-393-32100-5

- LeBlanc, Steven (2003).Constant battles: the myth of the peaceful, noble savage.New York: St Martin's PressISBN0-312-31089-7

- Lovejoy, Arthur O.(1923, 1943). "The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality," Modern Philology Vol. 21, No. 2 (Nov., 1923):165–186. Reprinted inEssays in the History of Ideas.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1948 and 1960.

- Lovejoy, A. O. and Boas, George ([1935] 1965).Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Books, 1965.ISBN0-374-95130-6

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. and George Boas. (1935).A Documentary History of Primitivism and Related Ideas,vol. 1. Baltimore.

- Moore, Grace (2004).Dickens And Empire: Discourses Of Class, Race And Colonialism In The Works Of Charles Dickens (Nineteenth Century Series).Ashgate.

- Olupọna, Jacob Obafẹmi Kẹhinde, Editor. (2003)Beyond primitivism: indigenous religious traditions and modernity.New York and London:Routledge.ISBN0-415-27319-6,ISBN978-0-415-27319-0

- Pagden, Anthony(1982).The Fall of the Natural Man: The American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pinker, Steven(2002).The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature.VikingISBN0-670-03151-8

- Sandall, Roger(2001).The Culture Cult: Designer Tribalism and Other EssaysISBN0-8133-3863-8

- Reinhardt, Leslie Kaye."British and Indian Identities in a Picture by Benjamin West".Eighteenth-Century Studies31: 3 (Spring 1998): 283–305

- Rollins, Peter C. and John E. O'Connor, editors (1998).Hollywood's Indian: the Portrayal of the Native American in Film.Le xing ton, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press.

- Tinker, Chaunchy Brewster (1922).Nature's Simple Plan: a phase of radical thought in the mid-eighteenth century.New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Torgovnick, Marianna (1991).Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives(Chicago)

- Whitney, Lois Payne (1934).Primitivism and the Idea of Progress in English Popular Literature of the Eighteenth Century.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press

- Wolf, Eric R.(1982).Europe and the People without History.Berkeley: University of California Press.