Northrop YF-23

| YF-23 | |

|---|---|

| |

| YF-23 flying overEdwards Air Force Base. | |

| Role | Stealth fightertechnology demonstrator |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Northrop/McDonnell Douglas |

| First flight | 27 August 1990 |

| Status | Canceled |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Produced | 1989–1990 |

| Number built | 2 |

TheNorthrop/McDonnell Douglas YF-23is an American single-seat,twin-engine,supersonicstealthfighter aircrafttechnology demonstrator designed for theUnited States Air Force(USAF). The design team was a finalist in the USAF'sAdvanced Tactical Fighter(ATF) demonstration/validation competition, battling theYF-22team for full-scale development and production. Two YF-23 prototypes were built.

In the 1980s, the USAF began looking for a replacement for itsF-15fighter aircraft to more effectively counter theSoviet Union's advancedSukhoi Su-27andMikoyan MiG-29.Several companies submitted design proposals; the USAF selected proposals fromNorthropandLockheed.Northrop teamed up withMcDonnell Douglasto develop the YF-23, while Lockheed,Boeing,andGeneral Dynamicsdeveloped the YF-22. The YF-23 was stealthier and faster, but less agile than its competitor. After a four-year development and evaluation process, the YF-22 team was announced as the winner in 1991 and developed theF-22 Raptor,which first flew in 1997 and entered service in 2005. The U.S. Navy considered using a naval version of the ATF as a replacement to theF-14,but these plans were later canceled due to costs.

After flight testing, both YF-23s were placed in storage while plans were considered by various agencies to use them for further research, although none proceeded. In 2004,Northrop Grumman[N 1]used the second YF-23 as a display model for its proposed regional bomber aircraft, but this project was dropped because longer range bombers were required. The two YF-23 prototypes are currently exhibits at theNational Museum of the United States Air Forceand theWestern Museum of Flightrespectively.

Development[edit]

Concept definition[edit]

American reconnaissance satellites first spotted the advanced SovietSu-27andMiG-29fighter prototypes in 1978, which caused concern in the U.S. Both Soviet models were expected to reduce the maneuverability advantages of contemporary U.S. fighter aircraft.[1]Additionally, U.S. tactical airpower would be further threatened by new Soviet systems such as theA-50airborne warning and control system(AWACS) and more advanced surface-to-air missile systems.[2]In 1981, the USAF began developing requirements and discussing with the aerospace industry on concepts for anAdvanced Tactical Fighter(ATF) to replace theF-15 Eagle.The ATF was to take advantage of emerging technologies, includingcomposite materials,lightweightalloys,advanced flight-control systems, more powerful propulsion systems, andstealth technology.[3]

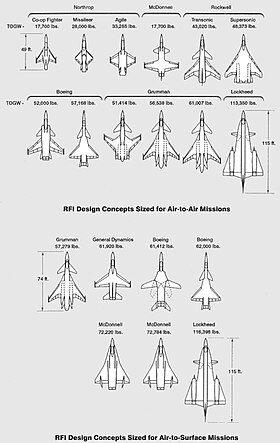

The ATFrequest for information(RFI) was released in May 1981 to several aerospace companies on possible features for the new fighter. Initially code-named"Senior Sky",the ATF at this time was still in the midst of requirements definition, which meant that there was considerable variety in the industry responses. Northrop submitted three designs for the RFI, ranging from ultra low-cost, to highly agile, to low-observable missileer; all were on the small and light end of the response spectrum.[4]In 1983, the ATF System Program Office (SPO) was formed atWright-Patterson Air Force Basefrom the initial Concept Development Team. After discussions with aerospace companies andTactical Air Command(TAC), the SPO madeair-to-air combatwith outstanding kinematic performance the primary role for the ATF, which would replace theF-15 Eagle.[5]Northrop's response was a Mach 2+ fighter design designated N-360 withdelta wings,a single vertical tail, and twin engines withthrust vectoringnozzles andthrust reversers.[6][7]Around this time, however, the SPO would begin to increasingly emphasize stealth for survivability and combat effectiveness due to very low radar cross section (RCS) results from the Air Force's "black world"innovations such as theHave Blue/F-117,Tacit Blue,and the Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) program (which would result in theB-2).[8]

Northrop was able to quickly adapt to the ATF's increasing emphasis on stealth. Since October 1981, a small team of engineers under Rob Sandusky within its ATB/B-2 division had been working on stealth fighter designs. Sandusky would later be the Northrop ATF's Chief Engineer, while fellow B-2 stealth engineer Yu Ping Liu was recruited in 1985 as the chief scientist.[9]Three design concepts were studied: the Agile Maneuverable Fighter (AMF) similar to N-360 with two canted vertical tails and the best aerodynamic performance of the three while having minimal stealth, Ultra Stealth Fighter (USF) that emphasized maximum stealth through edge alignment with only four RCS lobes and nicknamed "Christmas Tree" for itsplanformshape, and High Stealth Fighter (HSF) that balanced stealth and maneuverability withdiamond wings,all-moving V-tail "ruddervators"(or butterfly tails), engine exhaust troughs, and aligned edges.[10][11]HSF would take many design cues from the B-2 to reduce its susceptibility to radar andinfrareddetection, and Liu's understanding of both radar signatures and aerodynamics would lend itself to key design features, such as the shaping of the nose (nicknamed the "platypus" for the initial shape and pronounced chine edges) and canopy with theirGaussian surfaces.By 1985, HSF had evolved to be recognizably similar to the eventual YF-23 and emerged as the optimal balance of stealth and aerodynamic performance.[9][12]

Demonstration and validation[edit]

By November 1984, concept exploration had allowed the SPO to narrow its requirements and release the Statement of Operational Need, which called for a 50,000 lb (22,700 kg) takeoff weight fighter with stealth and excellent kinematics, including prolonged supersonic flight without the use ofafterburners,orsupercruise.In September 1985, the USAF issued therequest for proposal(RFP) for demonstration and validation (Dem/Val) to several aircraft manufacturers with the top four proposals, later cut down to two, proceeding to the next phase; in addition to the ATF's demanding technical requirements, the RFP also emphasizedsystems engineering,technology development plans, and risk mitigation.[13]The RFP would see some changes after its initial release; following discussions with Lockheed and Northrop regarding their experiences with the F-117 and ATB/B-2, stealth requirements were drastically increased in December 1985.[14]The requirement to include the evaluation of prototype air vehicles from the two finalists was added in May 1986 due to recommendations from thePackard Commission.At this time, the USAF envisioned procuring 750 ATFs at a unit flyaway cost of $35 million in fiscal year (FY) 1985 dollars (equivalent to $84,207,989 in 2023). Furthermore, the U.S. Navy, under the Navy Advanced Tactical Fighter (NATF) program, eventually announced that it would use a derivative of the ATF winner to replace itsF-14 Tomcatand called for the procurement of 546 aircraft.[15][16]

Northrop's work on the HSF would pay off for the Dem/Val RFP. By January 1986, the HSF would evolve into Design Proposal 86E (DP86E) as a refined and well-understood concept through extensivecomputational fluid dynamicssimulations,wind tunneltesting, and RCS pole testing and became Northrop's preference for its ATF submission.[17]Furthermore, Northrop's ability to design and analyze stealthy curved surfaces, stemming back to its work onTacit Blueand the ATB/B-2, gave their designers an early advantage, especially since Lockheed, the only other company with extensive stealth experience, had previously relied on faceting as on the F-117 andlost the ATBto Northrop as a result. That loss, along with the poor aerodynamic performance of their early faceted ATF concept, forced Lockheed to also develop designs and analysis methods with curved stealthy surfaces.[18][19]Northrop's HSF design would be refined into DP110, which was its submission for the Dem/Val RFP.[10]

In July 1986, proposals for Dem/Val were submitted byLockheed,Boeing,General Dynamics,McDonnell Douglas, Northrop,GrummanandRockwell;the latter two dropped out of the competition shortly thereafter.[20]As contractors were expected to make significant investments for technology development, companies forming teams was encouraged by the SPO. Following proposal submissions, Lockheed, Boeing, and General Dynamics formed a team to develop whichever of their proposed designs was selected, if any. Northrop and McDonnell Douglas formed a team with a similar agreement.[21]

Lockheed and Northrop, the two industry leaders in stealth aircraft, were selected as finalists on 31 October 1986 for Dem/Val as first and second place, although the approaches to their proposals were markedly different. Northrop's refined and well-understood design proposal was a significant advantage, especially in contrast to Lockheed's immature design, but the Lockheed proposal's focus on systems engineering rather than a point aircraft design actually pulled it ahead.[22][19]Both teams were awarded $691 million in FY 1985 dollars (equivalent to $1,662,506,297 in 2023) and given 50 months to build and flight-test their prototypes. Concurrently,Pratt & WhitneyandGeneral Electricwere contracted to develop the engines for the ATF engine competition.[23]Because of the late addition of the prototyping requirement due to political pressure, the prototype air vehicles were to be "best-effort" machines not meant to perform a competitive flyoff or represent a production aircraft that meets every requirement, but to demonstrate the viability of its concept and mitigate risk.[24]

Design refinement[edit]

As one of the winning companies for the Dem/Val proposals, Northrop was the program lead of the YF-23 team with McDonnell Douglas; the two had previously collaborated on theF/A-18 Hornet.[25]In addition to the government contract awards, the team would eventually invest $650 million (equivalent to $1,333,854,545 in 2023) combined into their ATF effort; General Electric and Pratt & Whitney, the two engine companies, also invested $100 million (equivalent to $222,309,091 in 2023) each.[26]Airframe fabrication was divided roughly evenly, with Northrop building the aft fuselage andempennageinHawthorne, Californiaand performing final assembly atEdwards Air Force Basewhile McDonnell Douglas built the wings and forward fuselage inSt. Louis, Missouri.Manufacturing was greatly assisted by the use ofcomputer-aided designsoftware. However, the YF-23 design would largely be a continual refinement from Northrop's DP110 with little influence from McDonnell Douglas's design, which had swept wings, four empennage surfaces, and chin-mounted split wedge inlets and did not perform well for stealth.[27]The YF-23's design evolved into DP117K when it was frozen as the prototype configuration in January 1988, with changes including a sharper and more voluminous nose from the earlier "platypus" shape for better radar performance and a strengthened aft deck with lower drag shaping.[28][29]Due to the complex surface curvature, the aircraft was built outside-in, with the large composite skin structures fabricated first before the internal members. To ensure precise and responsive handling, Northrop developed and tested the flight control laws using both a large-scale simulator as well as a modifiedC-131named the Total In Flight Simulator (TIFS).[30]

Throughout Dem/Val, the SPO conducted System Requirements Reviews (SRR) where it reviewed results of performance and costtrade studieswith both teams and, if necessary, adjusted requirements and deleted ones that added substantial weight or cost while having marginal value. The ATF was initially required to land and stop within 2,000 feet (610 m), which meant the use ofthrust reverserson their engines. In 1987, the USAF changed the runway length requirement to 3,000 feet (910 m) and by 1988 the requirement for thrust reversers was no longer needed. This allowed Northrop to have smaller enginenacellehousings in subsequent design refinements for the F-23. As DP117K had been frozen by then, the nacelles — nicknamed "bread loafs" for their flat upper surface — were not downsized on the prototypes.[31][32]The number of internal missiles (with theAIM-120Aas the reference baseline) was reduced from eight to six. Despite these adjustments, both teams struggled to achieve the 50,000-lb takeoff gross weight goal, and this was subsequently increased to 60,000 lb (27,200 kg) while engine thrust was increased from 30,000 lbf (133 kN) to 35,000 lbf (156 kN) class.[33]

Aside from advances in air vehicle and engine design, the ATF also required innovations in avionics and sensor systems with the goal of achievingsensor fusionto enhance situational awareness and reduce pilot workload. The YF-23 was meant as a demonstrator for the airframe and propulsion system design and thus did not mount any mission systems avionics. Instead, Northrop and McDonnell Douglas tested these systems on ground and airborne laboratories with Northrop using a modifiedBAC One-Elevenas a flying avionics laboratory and McDonnell Douglas building the Avionics Ground Prototype (AGP) to evaluate software and hardware performance and reliability.[25][34]Avionics requirements were also the subject of SPO SRRs with contractors and adjusted during Dem/Val. For example, theinfrared search and track(IRST) sensor was dropped from a baseline requirement to provision for future addition in 1989.[33]

Formally designated as the YF-23A, the first aircraft (serial number87-0800), Prototype Air Vehicle 1 (PAV-1), was rolled out on 22 June 1990;[35]PAV-1 took its 50-minutemaiden flighton 27 August with Alfred "Paul" Metz at the controls.[36]The second YF-23 (serial number87-0801,PAV-2) made its first flight on 26 October, piloted by Jim Sandberg.[37]The first YF-23 was painted charcoal gray and was nicknamed "Gray Ghost". The second prototype was painted in two shades of gray and nicknamed "Spider".[38]PAV-1 briefly had a red hourglass painted on its ram air scoop to prevent injury to ground crew. The red hourglass resembled the marking on the underside of the black widow spider further reinforcing the unofficial nickname "Black Widow II"[38]given to the YF-23 because of its 8-lobe radar cross section plot shape that resembled a spider. When Northrop management found out about the marking, they had it removed.[39]

[edit]

A proposed naval variant of the YF-23, sometimes known as the NATF-23 (the design was never formally designated), was considered as anF-14 Tomcatreplacement. The original YF-23 design was first considered but would have had issues with flight deck space, handling, storage, landing, and catapult launching, thus necessitating a different design. By 1989, the design was narrowed down to two possible configurations, DP533 with four tails and DP527 with two tails andcanards.DP527 was eventually determined to be the best solution.[40][41]The NATF-23 design was submitted along with the F-23 proposal for full-scale development, or engineering and manufacturing development (EMD), in December 1990, although by late 1990 the Navy was already beginning to back out of the NATF program and fully abandoned it by FY 1992 due to escalating costs.[42]A wind tunnel test model of DP527, tested for 14,000 hours, was donated (with canards removed) byBoeing St. Louis(formerly McDonnell Douglas) in 2001 to theBellefontaine NeighborsKlein Park Veterans Memorial in St. Louis, Missouri.[43]

Design[edit]

The YF-23A (internally designated DP117K) was a prototype air vehicle intended to demonstrate the viability of Northrop's ATF proposal designed to meet USAF requirements forsurvivability,supercruise, stealth, and ease of maintenance.[44]Owing to its continual maturation from the HSF concept which it still greatly resembled, the YF-23's shaping was highly refined. It was an unconventional-looking aircraft, with diamond-shaped wings, a profile with substantialarea-rulingto reduceaerodynamic dragattransonicandsupersonicspeeds, andall-movingV-tails,or "ruddervators".[45]Thecockpitwas placed high, near the nose of the aircraft, for good visibility for the pilot. The aircraft featured atricycle landing gearconfiguration with a noselanding gearleg and two main landing gear legs. A single large weapons bay was placed on the underside of the fuselage between the nose and main landing gear.[46]The cockpit had a center stick and side throttle.[47]

It was powered by twoturbofanengines, with each in a separate engine nacelle withS-ducts,to shield engineaxial compressorsfromradarwaves, on either side of the aircraft's spine.[48]The inlets were trapezoidal in frontal profile, with special porous suction panels in front to absorb the turbulentboundary layerand vent it over the wings. Of the two aircraft built, the first YF-23 (PAV-1) hadPratt & Whitney YF119engines, while the second (PAV-2) was powered byGeneral Electric YF120engines. The aircraft had single-expansion ramp nozzles (SERN) and, unlike the YF-22, did not employthrust vectoring.[31]As on the B-2, the exhaust from the YF-23's engines flowed through troughs lined with tiles that are “transpiration cooled” to dissipate heat and shield the engines frominfrared homing(IR) missile detection from below.[12]The YF-23's propulsion and aerodynamics enabled it to supercruise at over Mach 1.6 without afterburners.[49]

The YF-23 was statically unstable — havingrelaxed stability— and flown throughfly-by-wirewith theflight control surfacescontrolled by a central management computer system. Raising thewing flapsandaileronson one side and lowering them on the other providedroll.The V-tail fins were angled 50 degrees from the vertical.Pitchwas mainly provided by rotating these V-tail fins in opposite directions so their front edges moved together or apart.Yawwas primarily supplied by rotating the tail fins in the same direction. Test pilot Paul Metz stated that the YF-23 had superior highangle of attack(AoA) performance compared to legacy aircraft, with trimmed AoA of up to 60°.[50][51]Deflecting the wing flaps down and ailerons up on both sides simultaneously provided foraerodynamic braking.[52]To keep prototyping costs low despite the novel design, a number of "commercial off-the-shelf"components were used, including an F-15 nose wheel, F/A-18 main landing gear parts, and the forward cockpit components of theF-15E Strike Eagle.[12][37]

Production F-23[edit]

The proposed production F-23 configuration (DP231 for the F119 engine and DP232 for the F120 engine) for full-scale development, or Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD), would have differed from the YF-23 prototypes in several ways. Instead of a single weapons bay, the EMD design would instead have two tandem bays in the lengthened forward fuselage, with the forward bay designed for short rangeAIM-9missiles and the aft main bay forAIM-120missiles and bombs. AnM61rotary cannon would be installed on the left side of the forward fuselage. The F-23's overall length was slightly increased to 70 ft 5 in (21.46 m) while wingspan remained about the same. Fuselage volume was expanded, the nose was enlarged to accept mission systems, including the AESAradar,and the forebodychineswere less pronounced and raised to the samewaterlineheight as the leading edge of the wing. The deletion of thrust reversers enabled the engine nacelles to have a smaller, more rounded cross-section and the space between them filled in to preserve area-ruling. The inlet design changed from the trapezoidal profile with suction panels to a serrated semicircular with a compression bump. The fuselage and empennage trailing edge pattern would also have fewer serrations and the engine thrust lines were toed in at 1.5° off center. The EMD proposal had both single-seat F-23A and two-seat F-23B variants.[53]

NATF-23[edit]

The naval NATF-23 variant (internally designated DP527), the schematics of which surfaced in the 2010s, was different in many ways due to the requirements ofaircraft carrier operationsas well as a greater emphasis on long range sensors, weapons, andloitertime for fleet air defense.[54][N 2]The diamond wings were located as far back as possible, and the aircraft had ruddervators with more serrations to reduce length, folding wing capability for flight deck storage, reinforced landing gear, tailhook and slightly canted canards for increased maneuverability at low speeds to land onaircraft carriers,and thrust vectoring nozzles.[55]The inlet design was also different, being a quarter circle with serrations and a bumped compression surface. The internal weapons bay was split into two compartments by a bulkhead along the centerline in the forward fuselage to strengthen the aircraft's keel and would have accommodated the Navy's plannedAIM-152advanced air-to-air missiles (AAAM) as well as potentially theAGM-88 HARMandAGM-84 Harpoon.The bay doors would carry AIM-9 missiles and an M61 rotary cannon would be installed in the right wing. The NATF-23 had an increased 48 ft (14.63 m) wingspan, while length was reduced to 62 ft 8.5 in (19.11 m), the same as the F-14. Folded wingspan would be 23 ft 4 in (7.11 m). Like the Air Force version, the NATF-23 had both single-seat and two-seat variants.[42][41]

Proposed revival[edit]

In 2004,Northrop Grumman[N 1]proposed an F-23-based bomber called the FB-23[N 3]"Rapid Theater Attack" (RTA) to meet a USAF solicitation for an interim regional bomber, for which theFB-22andB-1Rwere also competing.[56][57]Northrop modified the YF-23 PAV-2 to serve as a display model for its proposed interim bomber.[58]The possibility of an FB-23 interim bomber ended with the 2006Quadrennial Defense Review,which favored a long-range strategic bomber with much greater range.[59][60]The USAF has since moved on to theNext-Generation BomberandLong Range Strike Bomberprogram.[61]

TheJapan Air Self-Defense Force(JASDF) launched a program to develop a domestic5th/6th generation(F-3) fighter after the US Congress refused in 1998 to export theF-22.After a great deal of study and the building of static models, theMitsubishi X-2 Shinshintestbed aircraft flew as a technology demonstrator from 2016. By July 2018, Japan had gleaned sufficient information and decided it would need to bring on-board international partners to complete this project. Northrop Grumman was one of the companies that responded and there was speculation that it could offer a modernized version of the F-23 to the JASDF, whileLockheed Martinoffered an airframe derived from the F-22; Japan ultimately did not select these proposals due to costs and industrial work-share concerns.[62][63]

Operational history[edit]

Evaluation[edit]

The first YF-23, with Pratt & Whitney engines, supercruised at Mach 1.43 on 18 September 1990, while the second, with General Electric engines, reached Mach 1.72 on 29 November 1990.[N 4]By comparison, the YF-22 achieved Mach 1.58 in supercruise.[64]The YF-23 was tested to a top speed of Mach 1.8 with afterburners and achieved a maximum angle-of-attack of 25°.[65]The maximum speed is classified, though sources state a speed greater than Mach 2 at altitude in full afterburner.[66][67]The aircraft's weapons bay was configured for weapons launch, and used for testing weapons bay acoustics, but no missiles were fired; Lockheed firedAIM-9 SidewinderandAIM-120 AMRAAMmissiles successfully from its YF-22 demonstration aircraft. PAV-1 performed a fast-paced combat demonstration with six flights over a 10-hour period on 30 November 1990. Flight testing continued into December.[68]The two YF-23s flew 50 times for a total of 65.2 hours.[69]The tests demonstrated Northrop's predicted performance values for the YF-23.[58]Both designs met or exceeded all performance requirements; the YF-23 was stealthier and faster, but the YF-22 was more agile.[70][71]

The two contractor teams submitted evaluation results with their proposals for full-scale development in December 1990,[58]and on 23 April 1991,Donald Rice,theSecretary of the Air Forceannounced that the YF-22 team was the winner.[72]The Air Force selected the Pratt & Whitney F119 engine to power the F-22 production version. The Lockheed and Pratt & Whitney designs were rated higher on technical aspects, considered lower risk (the YF-23 flew fewer sorties and hours than its counterpart), and were considered to have more effective program management.[73][72][58]It has been speculated in the aviation press that the Lockheed design was also seen as more adaptable as the basis for the Navy's NATF, but by FY 1992 the U.S. Navy had abandoned NATF.[74][75]

Following the competition, both YF-23s were transferred to NASA'sDryden Flight Research CenteratEdwards AFB,California, without their engines.[76][12]NASA planned to use one of the aircraft to study techniques for the calibration of predicted loads to measured flight results, but this did not happen.[76]Both YF-23 airframes remained in storage until mid-1996 when they were transferred to museums.[76][77]

Aircraft on display[edit]

- YF-23A PAV-1, Air Force serial number87-0800,"Gray Ghost", registration number N231YF, is on display in the Research and Development hangar of theNational Museum of the United States Air ForcenearDayton, Ohio.[78]

- YF-23A PAV-2, AF ser. no.87-0801,"Spider", registration number N232YF, was on exhibit at theWestern Museum of Flightuntil 2004,[76]when it was reclaimed by Northrop Grumman and used as a display model for an F-23-based bomber.[79]PAV-2 was returned to the Western Museum of Flight and was on display as of 2010 at the museum's new location atZamperini FieldinTorrance, California.[80]

Specifications (YF-23A)[edit]

Data fromPace,[81]Sweetman,[82]Winchester,[12]Metz & Sandberg,[66]Aronstein[67](note, some specifications are estimated)

General characteristics

- Crew:1

- Length:67 ft 5 in (20.55 m)

- Wingspan:43 ft 7 in (13.28 m)

- Height:13 ft 11 in (4.24 m)

- Wing area:950 sq ft (88 m2)

- Empty weight:32,000 lb (14,515 kg)

- Gross weight:64,000 lb (29,030 kg) takeoff, 51,320 lb (23,280 kg) combat weight

- Powerplant:2 ×Pratt & Whitney YF119orGeneral Electric YF120afterburning turbofanengines, 23,500 lbf (105 kN) thrust each (YF120) dry, 30,000 or 35,000 lbf (130 or 160 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed:Mach 2.2 (1,450 mph, 2,335 km/h) at high altitude

- Supercruise:Mach 1.72 (1,135 mph, 1,827 km/h) at altitude

- Range:2,424 nmi (2,789 mi, 4,489 km)

- Combat range:651–695 nmi (750–800 mi, 1,210–1,290 km)

- Service ceiling:65,000 ft (20,000 m)

- Wing loading:67.4 lb/sq ft (329 kg/m2) (54 lb/sq ft at combat weight)

- Thrust/weight:1.09 (1.36 at combat weight)

- Maximumg-load:+7.1g(highest tested)

Armament

None as tested but provisions made for:[12]

- 1 × 20 mm (0.79 in)M61 Vulcancannon

- 4 ×AIM-120 AMRAAMorAIM-7 Sparrowmedium-rangeair-to-air missiles[12][83]

- 2 ×AIM-9 Sidewindershort-range air-to-air missiles[83]

See also[edit]

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^abNorthrop acquired Grumman in 1994 to become Northrop Grumman.

- ^The DP527 drawings show the same F119 engines as the Air Force version, but the final powerplant may have been a modified variant with greater bypass ratio for improved fuel efficiency at the expense of supercruise performance.

- ^The "F/B-23" designation was also used.

- ^Speculation from aviation press reports suggests that the top supercruise speed of the YF-23 with GE engines was as high as Mach 1.8.[29]

Citations[edit]

- ^Rich, Michael; Stanley, William (April 1984)."Improving U.S. Air Force Readiness and Sustainability"(PDF).RAND Corporation.p. 7.

- ^Aronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,pp. 37–39.

- ^Miller 2005,p. 11.

- ^Metz 2017,pp. 10–12.

- ^Sweetman 1991b,pp. 10–13.

- ^Chong 2016,pp. 226–227.

- ^Metz 2017,pp. 228–229.

- ^Aronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,pp. 45–58.

- ^abMetz 2017,p. 23-24.

- ^abMetz 2017,pp. 28–29.

- ^Chong 2016,pp. 233–234.

- ^abcdefgWinchester 2005,pp. 198–199.

- ^Aronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,pp. 70–78.

- ^Aronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1999,pp. 82–85.

- ^Williams 2002,p. 5.

- ^Aronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,pp. 87–88.

- ^Metz 2017,p. 25.

- ^Hehs, Eric (1998)."Design Evolution of the F-22, Part 1".Code One.Lockheed Martin.

- ^abMetz 2017,p. 22.

- ^Miller 2005,pp. 13–14, 19.

- ^Goodall 1992,p. 94.

- ^Hehs, Eric (1998)."Design Evolution of the F-22, Part 2".Code One.Lockheed Martin.

- ^Jenkins & Landis 2008,pp. 233–234.

- ^Aronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,pp. 88–89.

- ^abMetz 2017,p. 31.

- ^Aronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,p. 164.

- ^Metz 2017,p. 20.

- ^Metz 2017,pp. 26–27.

- ^abChong 2016,pp. 237–238.

- ^Metz 2017,pp. 40–41.

- ^abMiller 2005,p. 23.

- ^Sweetman 1991a,pp. 23, 43.

- ^abAronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,pp. 106–108.

- ^Aronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,pp. 113–114.

- ^"YF-23 roll out marks ATF debut".Flight International.27 June - 3 July 1990. p. 5. Archived fromthe originalon 24 July 2012.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^Goodall 1992,p. 99.

- ^abJenkins & Landis 2008,p. 237.

- ^abYF-23 Walk Around and Design Features by Test Pilot Paul Metz.Western Museum of Flight: Peninsula Seniors Productions. 6 September 2015. Event occurs at 7:20.Retrieved15 June2024– via YouTube.

- ^Goodall 1992,p. 120.

- ^"Naval ATF to use Technologies Beyond Those in Air Force Version" 12 July 1990Aerospace Daily ASDp. 59, Vol. 155, No. 8 English, 1990. McGraw-Hill, Inc.

- ^abChong 2016,pp. 238–239.

- ^abMetz 2017,pp. 74–79.

- ^"Memorial Day's service will include unveiling of plane".St. Louis Post-Dispatch(Main ed.). 24 May 2001. p. 100 – viaNewspapers.

- ^"ATF procurement launches new era".Flight International.15 November 1986. p. 10. Archived fromthe originalon 24 July 2012.

- ^Metz 2017,p. 84.

- ^Goodall 1992,pp. 108–115, 124.

- ^Metz 2017,pp. 92–93.

- ^Sweetman 1991a,pp. 42–44, 55.

- ^"Northrop-McDonnell Douglas YF-23A Black Widow II".National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

- ^"YF-23 would undergo subtle changes if it wins competition".Defense Daily.170(8): 62–63. 14 January 1991 – via Gale.

- ^10 Percent True - Tales from the Cockpit (4 January 2022).YF-23 Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) - Paul Metz (Part 1).Retrieved15 June2024– via YouTube.

{{cite AV media}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Sweetman 1991a,pp. 34–35, 43–45.

- ^Metz 2017,p. 54.

- ^Report to the Chairman, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives: Navy's Participation in Air Force's Advanced Tactical Fighter Program(PDF)(Report). United States Government Accounting Office. March 1990.

- ^Simonsen, Erik (2016). "ATF Chapter 9".A Complete History of US Combat Aircraft Fly-Off Competitions.Specialty Press.ISBN9781580072274.

- ^Herbert, Adam J. (November 2004)."Long-Range Strike in a Hurry".Airforce Magazine.Archived fromthe originalon 25 August 2009.

- ^"YF-23 re-emerges for surprise bid".Flight International.13 July 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 23 July 2012.

- ^abcdMiller 2005,pp. 38–39.

- ^"Quadrennial Defense Review Report"(PDF).U.S. Department of Defense.6 February 2006. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 15 February 2007.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^Herbert, Adam J. (October 2006)."The 2018 Bomber and Its Friends".Airforce Magazine.Archived fromthe originalon 23 September 2009.

- ^Majumdar, Dave (23 January 2011)."U.S. Air Force May Buy 175 Bombers".Defense News.Archived fromthe originalon 4 September 2012.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^Mizokami, Kyle (9 July 2018)."Now Northrop Grumman Wants to Build Japan's New Fighter Jet".Popular Mechanics.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^"Defense Ministry to develop own fighter jet to succeed F-2, may seek int'l project".Mainichi Shimbun.4 October 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 25 April 2019.Retrieved28 April2019.

- ^Goodall 1992,pp. 102–103.

- ^"YF-23 would undergo subtle changes if it wins competition".Defense Daily.170(8): 62–63. 14 January 1991 – via Gale.

- ^abPaul Metz, Jim Sandberg (27 August 2015).YF-23 DEM/VAL Presentation by Test Pilots Paul Metz and Jim Sandberg.Western Museum of Flight: Peninsula Seniors Production.

- ^abAronstein, Hirschberg & Piccirillo 1998,p. 136.

- ^Miller 2005,pp. 36, 39.

- ^Norris, Guy."NASA could rescue redundant YF-23s".Flight International.5 - 11 June 1991. p. 16. Archived fromthe originalon 21 May 2011.

- ^Goodall 1992,p. 110.

- ^Sweetman 1991a,p. 55.

- ^abJenkins & Landis 2008,p. 234.

- ^Landis, Tony (1 February 2022).Flashback: Northrop YF-23 Black Widow II(Report). Air Force Materiel Command History Office.

- ^Williams 2002,p. 6.

- ^Miller 2005,p. 76.

- ^abcd"YF-23 Photo Gallery".NASA Dryden Flight Research Center.20 January 1996. Archived fromthe originalon 5 June 1997.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^"Flashback: Northrop YF-23 Black Widow II".U.S. Air Force Sustainment Center.1 February 2022.

- ^"Northrop-McDonnell Douglas YF-23A Black Widow II".National Museum of the United States Air Force™.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^Miller 2005,p. 39.

- ^"Static Displays";"Northrop YF-23A 'Black Widow II'".Western Museum of Flight.Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^Pace 1999,pp. 14–15.

- ^Sweetman 1991a,p. 93.

- ^abSweetman 1991a,pp. 42–43.

Bibliography[edit]

- Aronstein, David C.; Hirschberg, Michael J; Piccirillo, Albert C. (1998).Advanced Tactical Fighter to F-22 Raptor: Origins of the 21st Century Air Dominance Fighter.Arlington, Virginia: AIAA (American Institute of Aeronautics & Astronautics).ISBN978-1-56347-282-4.

- Chong, Tony (2016).Flying Wings & Radical Things, Northrop's Secret Aerospace Projects & Concepts 1939-1994.Forest Lake, Minnesota: Specialty Press.ISBN978-1-58007-229-8.

- Goodall, James C (1992). "The Lockheed YF-22 and Northrop YF-23 Advanced Tactical Fighters".America's Stealth Fighters and Bombers, B-2, F-117, YF-22, and YF-23.St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International Publishing.ISBN9780879386092.

- Jenkins, Dennis R.; Landis, Tony R. (2008).Experimental & Prototype U.S. Air Force Jet Fighters.North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press.ISBN978-1-58007-111-6.

- Metz, Alfred "Paul" (2017).Air Force Legends Number 220. Northrop YF-23 ATF.Forest Lake, Minnesota: Specialty Press.ISBN9780989258371.

- Miller, Jay (2005).Lockheed Martin F/A-22 Raptor, Stealth Fighter.Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing.ISBN9781857801583.

- Pace, Steve (1999).F-22 Raptor.New York: McGraw-Hill.ISBN9780071342711.

- Sweetman, Bill(1991a).YF-22 and YF-23 Advanced Tactical Fighters.St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International Publishing.ISBN9780879385057.

- Sweetman, Bill(1991b). "The Fighter They Didn't Want".World Air Power Journal.7(Autumn/Winter 1991). London: Aerospace Publishing.ISBN9781874023135.ISSN0959-7050.

- Williams, Mel, ed. (2002). "Lockheed Martin F-22A Raptor".Superfighters: The Next Generation of Combat Aircraft.London: AIRtime Publishing.ISBN9781880588536.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. (2005). "Northrop/McDonnell Douglas YF-23".Concept Aircraft.Rochester, Kent, UK: Grange Books.ISBN9781840138092.