Nurarihyon

You can helpexpand this article with text translated fromthe corresponding articlein Japanese.(May 2016)Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Nurarihyon(Hoạt gáo[1]or ぬらりひょん)is a Japaneseyōkai.

Concept[edit]

Generally, like thehyōtannamazu,they are considered a monster that cannot be caught.[1]One can find that it often appears in the yōkai emaki of the Edo Period, but any further details about it are unknown. In folktale legends, they are a member of theHyakki Yagyō(in theAkita Prefecture), and there is a type ofumibōzuin theOkayama prefecturethat can be found under that name, but it is not clear whether they came before or after the "nurarihyon" in the pictures.[2][3]

It has been thought that they are a "supreme commander of yōkai," but this has been determined to be simply a misinformed or common saying, as detailed in a later section.

In yōkai pictures[edit]

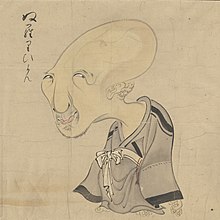

In the Edo Period Japanese dictionary, theRigen Shūran,there is only the explanation "monster painting byKohōgen Motonobu."[4]According to the Edo Period writingKiyū Shōran( đùa du cười lãm ), it can be seen that one of the yōkai that it notes is depicted in the Bakemono E ( hóa vật hội ) drawn byKōhōgen Motonobuis one by the name of "nurarihyon,"[5]and it is also depicted in theHyakkai Zukan(1737, Sawaki Suushi) and theHyakki Yagyō Emaki(1832, Oda Gōchō, in the Matsui Library), among many other emakimono. It is a bald old man with an elongated head, and depicted wearing either a kimono or akasaya.Without any explanatory text, it is unclear what kind of yōkai they were intending to depict.

TheKōshoku Haidokusan( háo sắc giải độc tán ), aukiyo-zōshipublished in the Edo Period gives the example, "its form was nurarihyon, like a catfish without eyes or mouth, the very spirit of lies," so it is known that it is word used with a meaning similar tonoppera-bōbut as an adjective.[3]

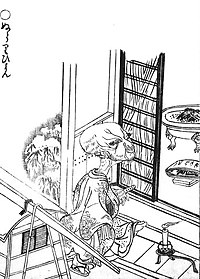

TheGazu Hyakki YagyōbyToriyama Sekiendepicts a nurarihyon hanging down from akago.Like the emakimono, this one has no explanatory text, so not many details are known, but the act of disembarking from a vehicle was called "nurarin," so it is thought that nurarihyon was a name given to a depiction of this.[3]Furthermore, it is also theorized that this depicts the libertines who go to the red light district.[6]Natsuhiko KyōgokuandKatsumi Tadaposit that "nurari" is an onomatopoeic word meaning the state of slipperiness, and "hyon" similarly means a strange or unexpected circumstances, which is why "nurarihyon" was the name given to a yōkai that was slippery (nurarikurari) because it cannot be caught.[6]In theGazu Hyakkai Yagyō,its name is written as "nūrihyon" but considering all the literature and emakimono before it, it is generally thought that this is simply a mistake.[4]

From its appearance, it is also theorized that this yōkai was born because an old person was mistaken for a yōkai.

Legends[edit]

Okayama Prefecture

According to Hirakawa Rinboku, in the legends ofOkayama Prefecture,the nurarihyon is considered similar toumibōzu,[7][2]and they are a round yōkai about as big as a human head that would float in theSeto Inland Sea,and when someone tries to catch it, it would sink and float back up over and over to taunt people.[6]It is thought that they would go "nurari" (an onomatopoeia) and slip from the hands, and float back up with a "hyon" (an onomatopoeia), which is why they were given this name.[3]

Presently, it is thought that these areportuguese man o' war,spotted jelly,and other large squid[6]and octopuses that have been seen as yōkai,[3]so it is thought that this is a different thing from the aforementioned nurarihyon that takes on the shape of an old person.[8]

Akita Prefecture

InYuki no Idewaji( tuyết の ra vũ lộ ) (1814) in theSugae Masumi Yūranki( "Sightseeing Records of Sugae Masumi" ) by the Edo Period travelerSugae Masumi,there is the following passage:

If you pass by the Sae no Kamizaka at evening among other times in a leisurely stroll with a light drizzle and thick clouds, there would be a man who meets with a woman, the woman would meet with the man, and nurarihyon,otoroshi,nozuchi,among others would go on ahyakki yagyō,so some call it the bakemonozaka (monster hill).[9]

In the same book is written that the "Sae no Kamizaka" ( Đạo Tổ ノ thần bản ) is in the town of Sakuraguchi, Inaniwa,Ogachi DistrictDewa Province(now the town of Inaniwa,Yuzawa,Akita Prefecture).[10]

Modern nurarihyon[edit]

Starting in the Shōwa, and Heisei eras, yōkai-related literature, children's books, and illustrated references note that the "nurarihyon" would enter people's homes in the evening when the people there are busy and then drink tea and smoke like it's their own home. It is explained that when they are seen, they would be thought of "as the owner of the house," so wouldn't be chased it away, or even noticed. They are also noted to be a "supreme commander of yōkai."[11]

However, folk legends that mention these characteristics cannot be found in any examples or references, so the yōkai researchers,Kenji MurakamiandKatsumi Tadaposit that the thought of them coming into houses comes from the following passage in theYōkai Gadan Zenshū Nihonhen Jō( yêu quái họa nói toàn tập Nhật Bản thiên thượng, "Discussion on Yōkai Pictures, Japan Volume, First Half" ) byMorihiko Fujisawa,where the following is written below Toriyama Sekien's illustration of the nurarihyon in that book:

While night is still approaching, the nurarihyon comes to visit as the chief monster.[12]

Those two yōkai researchers posit that this caption resulted in the proliferation of this thought in later years, and that this was actually a made-up idea that came from an interpretation of Toriyama Sekien's picture.[6][2]Murakami and Tada posit that in fact, Fujisawa's assertion that the "nurarihyon comes to visit as the chief monster" is nothing more than a big guess.[6][2]

Also, inWakayama Prefecture,stories where a nurarihyon appear were published to explain them,[13]but those stories originate from a story titled "Nurarihyon" in the collection of writings, "Obake Bunko 2, Nurarihyon" (Library of Monsters 2: Nurarihyon) byNorio Yamada,and it is thought that this is also made-up.[6]

Toward the end of the Shōwa period, on the basis of Fujisawa's interpretation given by the caption, the thought that they "come into one's home" or that they are a "supreme commander of yōkai" took a life of its own afterMizuki ShigeruandArifumi Satōspread them through their own illustrated yōkai reference books,[3]and in the animated television series, the 3rd "GeGeGe no Kitarō" (starting in 1985), a nurarihyon was the antagonist and arch-enemy of the main character Kitarō, and was a self-proclaimed "supreme commander," which altogether can be seen as things that made their perception as being "supreme commanders" even more famous.[14]

The literary scholarKunihiro Shimurastates that all these above characteristics have made the legend stray far from its original meaning and made it artificially distorted.[2]On the other hand, Natsuhiko Kyōgoku states that in his opinion, this yōkai is performing its function just fine in its present form so there is no problem,[15]and that by understanding yōkai as a part of a living culture, he does not mind that they change to fit with the times.[16]Natsuhiko Kyōgoku participated in the animated television series, the 4th "Gegege no Kitarō" as a guest writer for the 101st episode, but here, the nurarihyon would be in its original form, as an octopus.

They are also depicted as inHell Teacher Nūbēas a ruined visitor god.

Etymology[edit]

The name Nurarihyon is aportmanteauof the words "Nurari" (Japanese: ぬらり or hoạt ) meaning "to slip away" and "hyon" (Japanese: ひょん or gáo ), anonomatopoeiaused to describe something floating upwards. In the name, the sound "hyon" is represented by the character for "gourd".[17]The Nurarihyon is unrelated to another,similarly named ocean YōkaifromOkayama Prefecture.[18]

Appearance and behaviour[edit]

The Nurarihyon is usually depicted as an old man with agourd-shaped head and wearing akesa.[17]In some depictions he also carries a single sword rather than the standard two to demonstrate his wealth. There is speculation that in Toriyama Sekien’s portrayal of Nurarihyon, he serves as a political cartoon to represent the aristocracy.[19]Others suggest that he is retired from a samurai family due to the sword and his clothing style.[20]

The Nurarihyon is often depicted sneaking into people's houses while they are away, drinking their tea, and acting as if it is their own house.[18][21]However, this depiction is not one based in folklore, but one based on hearsay and repeated in popular Yōkai media.[18][22]

Notes[edit]

- ^ab『 quảng từ uyển 』 thứ năm bảnNham sóng hiệu sách2006 năm.

- ^abcdeThôn thượng 2000,pp. 255–258

- ^abcdefChí thôn 2011,pp. 73–75

- ^abĐạo điền hết lòng tin theo ・ điền trung thẳng ngày biên (1992).Cao điền vệGiam tu (ed.).Điểu núi đá yến họa đồ bách quỷ dạ hành.Quốc thư phát hành sẽ.pp. 84 trang.ISBN978-4-336-03386-4.

- ^Đạo điền hết lòng tin theo ・ điền trung thẳng ngày biên (1992).Cao điền vệGiam tu (ed.).Điểu núi đá yến họa đồ bách quỷ dạ hành.Quốc thư phát hành sẽ.pp. 81 trang.ISBN978-4-336-03386-4.

- ^abcdefgNhiều điền 2000,p. 149

- ^Đồng bằng cây rừng “Sơn dương lộ の yêu quái” ( tập san quý 『 tự nhiên と văn hóa 』1984 nămMùa thu hào Nhật Bản ナショナルトラスト 44-45 trang )

- ^Thôn thượng kiện tưHắn biên (2000).Bách quỷ dạ hành giải thể sách mới.コーエー.p. 90.ISBN978-4-87719-827-5.

- ^Phúc đảo bân người『 kỳ 々 quái 々あきた vân thừa 』Vô minh xá1999 năm 133 trangISBN4-89544-219-5

- ^Thu điền bộ sách phát hành sẽ 『 thu điền bộ sách 』 đệ tam quyển ( 『 tuyết の ra vũ lộ 』 hùng thắng quận nhị ) 137 trang

- ^Thủy mộc しげる『 quyết định bản Nhật Bản yêu quái bách khoa toàn thư yêu quái ・あ の thế ・ thần dạng 』Giảng nói xã(Giảng nói xã kho sách) 2014 nămISBN978-4-06-277602-8533 trang

- ^Đằng trạch vệ ngạn 『 yêu quái họa nói toàn tập Nhật Bản thiên thượng 』 trung ương mỹ thuật xã1929 năm291 trang

- ^Thủy mộc しげる『 Nhật Bản yêu quái bách khoa toàn thư 』Giảng nói xã1991 nămISBN4-06-313210-2330 trang

- ^Cung bổn hạnh chi ・ hùng cốc あづさ (2007).Nhật Bản の yêu quái の mê と không tư nghị.GAKKEN MOOK.Học tập nghiên cứu xã.p. 83.ISBN978-4-05-604760-8.

- ^Kinh cực hạ ngạn(2008).Đối nói tập yêu quái đại nói nghĩa.Giác xuyên kho sách.Giác xuyên hiệu sách.p. 50.ISBN978-4-04-362005-0.

- ^Thủy mộc しげる・ kinh cực hạ ngạn (1998).Thủy mộc しげるvs. Kinh cực hạ ngạn ゲゲゲ の quỷ quá lang giải thể sách mới.Giảng nói xã.pp. 24–25.ISBN978-4-06-330048-2.

- ^abMeyer 2013,p. "Nurarihyon".

- ^abcFoster & Kijin 2014,p. 218.

- ^Yoda 2016,p. 64.

- ^Zenyōji 2015,p. 230.

- ^Mizuki 1994,p. 344-345.

- ^Kyōgoku & Tada 2000,p. 149.

References[edit]

- Nhiều điền khắc kỷ(2000).Kinh cực hạ ngạn・ nhiều điền khắc kỷ biên (ed.).Yêu quái đồ quyển.Quốc thư phát hành sẽ.ISBN978-4-336-04187-6.

- Thôn thượng kiện tư biên (2000).Yêu quái sự điển.Mỗi ngày tin tức xã.ISBN978-4-620-31428-0.

- Davisson, Zack (March 2015). "Back Matter: Nurarihyon".Wayward Volume One: String Theory.Image Comics.ISBN978-1-63215-173-5.

- Foster, Michael Dylan; Kijin, Shinonome (2014).The Book of Yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore.University of California Press.ISBN9780520271029.

- Kyōgoku, Natsuhiko; Tada, Katsumi (2000).Yōkai Zukan.Kokusho Kankōkai.ISBN978-4336041876.

- Meyer, Matthew (2013)."Nurarihyon".yokai.Retrieved22 May2016.

- Mizuki, Shigeru (1994).Zusetsu Nihon Yōkai Taizen.Kōdansha.ISBN9784062776028.

- Murakami, Kenji (2000).Yōkai Jiten.Mainichi Shinbunsha.ISBN978-4620314280.

- Yoda, Hiroko (2016).Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yōkai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien.Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc.ISBN9780486800356.

- Zenyōji, Susumu (2015).E de miru Edo no yōkai zukan.Tokyo: Kōsaidō Shuppan.ISBN9784331519578.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Nurarihyon – The Slippery Gourdat hyakumonogatari (English).

- Nurarihyon from Yōkai on Mizuki Shigeru Road: Sakaiminato Sightseeing Guide(in Japanese)