Ojibwe

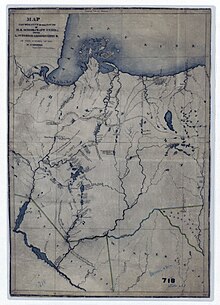

Precontact distribution of Ojibwe-speaking people | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 170,742 in United States (2010)[1] 160,000 in Canada (2014)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada (Quebec,Ontario,Manitoba,Saskatchewan,Alberta) United States (Michigan,Wisconsin,Minnesota,North Dakota,Montana) | |

| Languages | |

| English,Ojibwe,French | |

| Religion | |

| Ojibwe religion,Catholicism,Methodism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Assiniboine,otherAlgonquian peoples Especially otherAnishinaabe,Cree,andMétis |

| Person | Ojibweᐅᒋᐺ Anishinaabe ᐊᓂᔑᓈᐯ |

|---|---|

| People | Ojibweg ᐅᒋᐺᒃ / ᐅᒋᐺᐠ Anishinaabek ᐊᓂᔑᓈᐯᒃ / ᐊᓂᔑᓈᐯᐠ |

| Language | Ojibwemowinᐅᒋᐺᒧᐎᓐ Anishinaabemowin ᐊᓂᐦᔑᓈᐯᒧᐎᓐ |

| Country | Ojibwewaki[3] Anishinaabewaki ᐊᓂᔑᓈᐯᐘᑭ |

TheOjibwe(syll.:ᐅᒋᐺ;plural:Ojibwegᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are anAnishinaabepeople whose homeland (Ojibwewakiᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ)[3]covers much of theGreat Lakesregion and thenorthern plains,extending into thesubarcticand throughout the northeastern woodlands. Ojibweg, beingIndigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlandsand ofthe subarctic,are known by several names, includingOjibwayorChippewa.As a largeethnic group,several distinct nations also consider themselves Ojibwe, including theSaulteaux,Nipissings,andOji-Cree.

According to the U.S. census, Ojibwe people are one of the largest tribal populations amongNative Americanpeoples in the U.S. In Canada, they are the second-largestFirst Nationspopulation, surpassed only by theCree.They are one of the most numerousIndigenous peoplesnorth of theRio Grande.[4][better source needed]The Ojibwe population is approximately 320,000, with 170,742 living in the U.S. as of 2010[update][1]and approximately 160,000 in Canada.[2]In the U.S. there are 77,940 mainline Ojibwe, 76,760 Saulteaux, and 8,770 Mississauga, organized in 125 bands. In Canada they live from westernQuebecto easternBritish Columbia.

The Ojibwe language isAnishinaabemowin,a branch of theAlgonquian language family.

The Ojibwe are part of theCouncil of Three Fires(along with theOdawaandPotawatomi) and of the larger Anishinaabeg, which includesAlgonquin,Nipissing,andOji-Creepeople. Historically, through theSaulteauxbranch, they were part of theIron Confederacy,with the Cree,Assiniboine,andMetis.[5]

The Ojibwe are known for theirbirchbarkcanoes,birchbark scrolls,mining and trade incopper,and their harvesting ofwild riceandmaple syrup.[6]TheirMidewiwinSociety is well respected as the keeper of detailed and complex scrolls of events, oral history, songs, maps, memories, stories, geometry, and mathematics.[7][failed verification]

European powers, Canada, and the U.S. have colonized Ojibwe lands. The Ojibwe signed treaties with settler leaders to surrender land for settlement in exchange for compensation, land reserves and guarantees of traditional rights. Many European settlers moved into the Ojibwe ancestral lands.[2]

Etymology

[edit]Theexonymfor this Anishinaabe group isOjibwe(plural:Ojibweg). This word has two variations, one French (Ojibwa) and the other English (Chippewa).[8]Althoughmany variationsexist in the literature,Chippewais more common in the United States, andOjibwaypredominates in Canada,[9]but both terms are used in each country. In many Ojibwe communities throughout Canada and the U.S. since the late 20th century, more members have been using the generalized nameAnishinaabe(-g).

The meaning of the nameOjibweis not known; the most common explanations for the name's origin are:

- ojiibwabwe(/o/ + /jiibw/ + /abwe/), meaning "those who cook/roast until it puckers", referring to their fire-curing ofmoccasinseams to make them waterproof.[10]Some 19th century sources say this name described a method of ritual torture that the Ojibwe applied to enemies.[11]

- ozhibii'iwe(/o/ + /zhibii'/ + /iwe/), meaning "those who keep records [of a Vision]", referring to their form ofpictorial writing,andpictographsused in Midewiwin sacred rites;[12]or

- ojiibwe(/o/ + /jiib/ + /we/), meaning "those who speak stiffly" or "those who stammer", an exonym or name given to them by theCree,who described the Ojibwe language for its differences from their own.[13]

Because many Ojibwe were formerly located around the outlet ofLake Superior,which theFrenchcolonists calledSault Ste. Mariefor its rapids, the early Canadian settlers referred to the Ojibwe asSaulteurs.Ojibwe who subsequently moved to the prairie provinces of Canada have retained the name Saulteaux. This is disputed since some scholars believe that only the name migrated west.[14][page needed]Ojibwe who were originally located along theMississagi Riverand made their way tosouthern Ontarioare known as theMississaugas.[15]

Language

[edit]The Ojibwe language is known asAnishinaabemowinorOjibwemowin,and is still widely spoken, although the number of fluent speakers has declined sharply.[16]Today, most of the language's fluent speakers are elders. Since the early 21st century, there is a growing movement to revitalize the language and restore its strength as a central part of Ojibwe culture. The language belongs to the Algonquian linguistic group and is descended fromProto-Algonquian.Its sister languages includeBlackfoot,Cheyenne,Cree,Fox,Menominee,Potawatomi,andShawneeamong the northern Plains tribes.Anishinaabemowinis frequently referred to as a "Central Algonquian" language; Central Algonquian is an area grouping, however, rather than a linguistic genetic one.

Ojibwemowinis the fourth-most spoken Native language in North America afterNavajo,Cree, andInuktitut.Many decades offur tradingwith the French established the language as one of the key trade languages of theGreat Lakesand the northernGreat Plains.

The popularity of theepic poemThe Song of Hiawatha,written byHenry Wadsworth Longfellowin 1855, publicized the Ojibwe culture. The epic contains manytoponymsthat originate from Ojibwe words.

History

[edit]Precontact and spiritual beliefs

[edit]According to Ojibweoral historyand from recordings in birch bark scrolls, the Ojibwe originated from the mouth of theSaint Lawrence Riveron theAtlantic coastof what is nowQuebec.[17]They traded widely across the continent for thousands of years as they migrated, and knew of the canoe routes to move north, west to east, and then south in the Americas. The identification of the Ojibwe as a culture or people may have occurred in response to contact with Europeans. The Europeans preferred to deal with groups, and tried to identify those they encountered.[18]

According to Ojibwe oral history, seven greatmiigis(Cowrie shells) appeared to them in theWaabanakiing(Land of the Dawn, i.e., Eastern Land) to teach them themidewayof life. One of themiigiswas too spiritually powerful and killed the people in theWaabanakiingwhen they were in its presence. The six others remained to teach, while the one returned into the ocean. The six establisheddoodem(clans) for people in the east, symbolized by animals. The five original Anishinaabedoodemwere theWawaazisii(Bullhead),Baswenaazhi(Echo-maker, i.e.,Crane),Aan'aawenh(PintailDuck),Nooke(Tender, i.e.,Bear) andMoozoonsii(LittleMoose). The sixmiigisthen returned to the ocean as well. If the seventh had stayed, it would have established theThunderbirddoodem.

At a later time, one of thesemiigisappeared in a vision to relate a prophecy. It said that if the Anishinaabeg did not move farther west, they would not be able to keep their traditional ways alive because of the many new pale-skinned settlers who would arrive soon in the east. Their migration path would be symbolized by a series of smaller Turtle Islands, which was confirmed withmiigisshells (i.e.,cowryshells). After receiving assurance from their "Allied Brothers" (i.e.,Mi'kmaq) and "Father" (i.e.,Abenaki) of their safety to move inland, the Anishinaabeg gradually migrated west along the Saint Lawrence River to theOttawa RivertoLake Nipissing,and then to the Great Lakes.

The first of the smaller Turtle Islands wasMooniyaa,whereMooniyaang(present-dayMontreal)[19]developed. The "second stopping place" was in the vicinity of theWayaanag-gakaabikaa(Concave Waterfalls, i.e.,Niagara Falls). At their "third stopping place", near the present-day city ofDetroit, Michigan,the Anishinaabeg divided into six groups, of which the Ojibwe was one.

The first significant new Ojibwe culture-center was their "fourth stopping place" onManidoo Minising(Manitoulin Island). Their first new political-center was referred to as their "fifth stopping place", in their present country atBaawiting(Sault Ste. Marie). Continuing their westward expansion, the Ojibwe divided into the "northern branch", following the north shore of Lake Superior, and the "southern branch", along its south shore.

As the people continued to migrate westward, the "northern branch" divided into a "westerly group" and a "southerly group". The "southern branch" and the "southerly group" of the "northern branch" came together at their "sixth stopping place" on Spirit Island (46°41′15″N092°11′21″W/ 46.68750°N 92.18917°W) located in theSaint Louis Riverestuary at the western end of Lake Superior. (This has since been developed as the present-dayDuluth/Superiorcities.) The people were directed in a vision by themiigisbeing to go to the "place where there is food (i.e.,wild rice) upon the waters. "Their second major settlement, referred to as their" seventh stopping place ", was at Shaugawaumikong (orZhaagawaamikong,French,Chequamegon) on the southern shore of Lake Superior, near the presentLa Pointe, Wisconsin.

The "westerly group" of the "northern branch" migrated along theRainy River,Red River of the North,and across the northern Great Plains until reaching thePacific Northwest.Along their migration to the west, they came across manymiigis,or cowry shells, as told in the prophecy.

Contact with Europeans

[edit]

The first historical mention of the Ojibwe occurs in the FrenchJesuit Relationof 1640, a report by the missionary priests to their superiors in France. Through their friendship with the French traders (coureurs des boisandvoyageurs), the Ojibwe gained guns, began to use European goods, and began to dominate their traditional enemies, theLakotaandFoxto their west and south. They drove the Sioux from the UpperMississippiregion to the area of the present-day Dakotas, and forced the Fox down from northernWisconsin.The latter allied with theSaukfor protection.

By the end of the 18th century, the Ojibwe controlled nearly all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of theRed Riverarea. They also controlled the entire northern shores of lakesHuronand Superior on the Canadian side and extending westward to theTurtle MountainsofNorth Dakota.In the latter area, the French Canadians called them Ojibwe orSaulteaux.

The Ojibwe were part of a long-term alliance with the AnishinaabeOdawaandPotawatomipeoples, called theCouncil of Three Fires.They fought against theIroquois Confederacy,based mainly to the southeast of the Great Lakes in present-dayNew York,and the Sioux to the west. The Ojibwa stopped the Iroquois advance into their territory near Lake Superior in 1662. Then they formed an alliance with other tribes such as theHuronand the Odawa who had been displaced by the Iroquois invasion. Together they launched a massive counterattack against the Iroquois and drove them out of Michigan and southern Ontario until they were forced to flee back to their original homeland in upstate New York. At the same time the Iroquois were subjected to attacks by the French. This was the beginning of the end of the Iroquois Confederacy as they were put on the defensive. The Ojibwe expanded eastward, taking over the lands along the eastern shores of Lake Huron andGeorgian Bay.

In 1745, they adopted guns from the British in order to repel theDakota peoplein the Lake Superior area, pushing them to the south and west. In the 1680s the Ojibwa defeated theIroquoiswho dispersed their Huron allies and trading partners. This victory allowed them a "golden age"in which they ruled uncontested in southern Ontario.[20]

Often, treaties known as "peace and friendship treaties" were made to establish community bonds between the Ojibwe and the European settlers. These established the groundwork for cooperative resource-sharing between the Ojibwe and the settlers. The United States and Canada viewed later treaties offering land cessions as offering territorial advantages. The Ojibwe did not understand the land cession terms in the same way because of the cultural differences in understanding the uses of land. The governments of the U.S. and Canada considered land a commodity of value that could be freely bought, owned and sold. The Ojibwe believed it was a fully shared resource, along with air, water and sunlight—despite having an understanding of "territory". At the time of the treaty councils, they could not conceive of separate land sales or exclusive ownership of land. Consequently, today, in both Canada and the U.S., legal arguments in treaty-rights and treaty interpretations often bring to light the differences in cultural understanding of treaty terms to come to legal understanding of the treaty obligations.[21]

In part because of its long trading alliance, the Ojibwe allied with the French against Great Britain and its colonists in theSeven Years' War(also called theFrench and Indian War).[22]After losing the war in 1763, France was forced to cede its colonial claims to lands in Canada and east of the Mississippi River to Britain. AfterPontiac's Warand adjusting to British colonial rule, the Ojibwe allied with British forces and against the United States in theWar of 1812.They had hoped that a British victory could protect them against United States settlers' encroachment on their territory.

Following the war, the United States government tried to forciblyremoveall the Ojibwe toMinnesota,west of the Mississippi River. The Ojibwe resisted, and there were violent confrontations. In theSandy Lake Tragedy,several hundred Ojibwe died because of the federal government's failure to deliver fall annuity payments.[23]The government attempted to do this in theKeweenaw Peninsulain theUpper Peninsula of Michigan.Through the efforts ofChief Buffaloand the rise of popular opinion in the U.S. against Ojibwe removal, the bands east of the Mississippi were allowed to return to reservations on ceded territory. A few families were removed toKansasas part of thePotawatomi removal.

In British North America, theRoyal Proclamation of 1763following the Seven Years' War governed the cession of land by treaty or purchase. Subsequently, France ceded most of the land inUpper Canadato Great Britain. Even with theJay Treatysigned between Great Britain and the United States following theAmerican Revolutionary War,the newly formed United States did not fully uphold the treaty. As it was still preoccupied by war with France, Great Britain ceded to the United States much of the lands inOhio,Indiana,Michigan, parts ofIllinoisand Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota and North Dakota to settle the boundary of their holdings in Canada.

In 1807, the Ojibwe joined three other tribes, the Odawa, Potawatomi and Wyandot people, in signing theTreaty of Detroit.The agreement, between the tribes andWilliam Hull,representing theMichigan Territory,gave the United States a portion of today'sSoutheastern Michiganand a section of Ohio near theMaumee River.The tribes were able to retain small pockets of land in the territory.[24]

TheBattle of the Brulewas an October 1842 battle between theLa PointeBand of Ojibwe Indians and a war party ofDakotaIndians. The battle took place along theBrule River(Bois Brûlé) in what is today northern Wisconsin and resulted in a decisive victory for the Ojibwe.

In Canada, many of the land cession treaties the British made with the Ojibwe provided for their rights for continued hunting, fishing and gathering of natural resources after land sales. The government signed numbered treaties in northwestern Ontario,Manitoba,Saskatchewan,andAlberta.British Columbiahad not signed treaties until the late 20th century, and most areas have no treaties yet. The government and First Nations are continuing to negotiate treaty land entitlements and settlements. The treaties are constantly being reinterpreted by the courts because many of them are vague and difficult to apply in modern times. The numbered treaties were some of the most detailed treaties signed for their time. The Ojibwe Nation set the agenda and negotiated the first numbered treaties before they would allow safe passage of many more British settlers to the prairies.

Ojibwe communities have a strong history of political and social activism. Long before contact, they were closely aligned with Odawa and Potawatomi people in the Council of the Three Fires. From the 1870s to 1938, the Grand General Indian Council of Ontario attempted to reconcile multiple traditional models into one cohesive voice to exercise political influence over colonial legislation. In the West, 16 Plains Cree and Ojibwe bands formed the Allied Bands of Qu'Appelle in 1910 in order to redress concerns about the failure of the government to uphold Treaty 4's promises.

Culture

[edit]

The Ojibwe have traditionally organized themselves into groups known asbands.Most Ojibwe, except for the Great Plains bands, have historically lived a settled (as opposed to nomadic) lifestyle, relying on fishing and hunting to supplement the cultivation of numerous varieties ofmaizeandsquash,and the harvesting ofmanoomin(wild rice) for food. Historically their typical dwelling has been thewiigiwaam(wigwam), built either as awaginogaan(domed-lodge) or as anasawa'ogaan(pointed-lodge), made of birch bark,juniperbark andwillowsaplings. In the contemporary era, most of the people live in modern housing, but traditional structures are still used for special sites and events.

They have a culturally-specific form of pictorial writing, used in the religious rites of theMidewiwinand recorded on birch bark scrolls and possibly on rock. The many complex pictures on the sacred scrolls communicate much historical, geometrical, and mathematical knowledge, as well as images from their spiritual pantheon. The use ofpetroforms,petroglyphs,andpictographshas been common throughout the Ojibwe traditional territories. Petroforms andmedicine wheelshave been used to teach important spiritual concepts, record astronomical events, and to use as amnemonic devicefor certain stories and beliefs. The script is still in use, among traditional people as well as among youth on social media.

Some ceremonies use themiigisshell (cowry shell), which is found naturally in distant coastal areas. Their use of such shells demonstrates there is a vast, longstanding trade network across the continent. The use and trade ofcopperacross the continent has also been proof of a large trading network that took place for thousands of years, as far back as theHopewell tradition.Certain types of rock used for spear and arrow heads have also been traded over large distances precontact.

During the summer months, the people attendjiingotamogfor the spiritual andniimi'idimaafor a social gathering (powwows) at various reservations in the Anishinaabe-Aki (Anishinaabe Country). Many people still follow the traditional ways of harvesting wild rice, picking berries, hunting, making medicines, and makingmaple sugar.

The jingle dress that is typically worn by female pow wow dancers originated from the Ojibwe. Both Plains and Woodlands Ojibwe claim the earliest form of dark cloth dresses decorated with rows of tin cones - often made from the lids of tobacco cans- that make a jingling sound when worn by the dancer. This style of dress is now popular with all tribes and is a distinctly Ojibwe contribution to Pan-Indianism.[25]

The Ojibwe bury their dead inburial mounds.Many erect ajiibegamigor a "spirit-house" over each mound. An historical burial mound would typically have a wooden marker, inscribed with the deceased'sdoodem(clan sign). Because of the distinct features of these burials, Ojibwe graves have been often looted by grave robbers. In the United States, many Ojibwe communities safe-guard their burial mounds through the enforcement of the 1990Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

Several Ojibwe bands in the United States cooperate in theGreat Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission,which manages the treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Lake Superior-Lake Michiganareas. The commission follows the directives of U.S. agencies to runseveral wilderness areas.Some Minnesota Ojibwe tribal councils cooperate in the1854 Treaty Authority,which manages their treaty hunting and fishing rights in theArrowhead Region.In Michigan, the Chippewa-Ottawa Resource Authority manages the hunting, fishing and gathering rights about Sault Ste. Marie, and the resources of the waters of lakes Michigan and Huron. In Canada, the Grand Council of Treaty No. 3 manages theTreaty 3hunting and fishing rights related to the area aroundLake of the Woods.

Cuisine

[edit]

There is renewed interest in nutritious eating among the Ojibwe, who have been expanding community gardens infood deserts,and have started a mobile kitchen to teach their communities about nutritious food preparation.[26]The traditional Native American diet was seasonally dependent on hunting, fishing and the foraging and farming of produce and grains. The modern diet has substituted some other types of food likefrybreadand "Indian tacos" in place of these traditionally prepared meals. The Native Americans loss of connection to their culture is part of the "quest to reconnect to their food traditions" sparking an interest in traditional ingredients likewild rice,that is the official state grain of Minnesota and Michigan, and was part of the pre-colonial diet of the Ojibwe. Other staple foods of the Ojibwe were fish, maple sugar, venison and corn. They grew beans, squash, corn and potatoes and foraged for blueberries, blackberries, choke cherries, raspberries, gooseberries and huckleberries. During the summer game animals like deer, beaver, moose, goose, duck, rabbits and bear were hunted.[27][28]

One traditional method of making granulated sugar known among the Anishinabe was to boilmaple syrupuntil reduced and pour into a trough, where the rapidly cooling syrup was quickly processed into maple sugar using wooden paddles.[29]

Kinship and clan system

[edit]Traditionally, the Ojibwe had apatrilinealsystem, in which children were considered born to the father'sclan.[30]For this reason, children with French or English fathers were considered outside the clan and Ojibwe society unless adopted by an Ojibwe male. They were sometimes referred to as "white" because of their fathers, regardless if their mothers were Ojibwe, as they had no official place in the Ojibwe society. The people would shelter the woman and her children, but they did not have the same place in the culture as children born to Ojibwe fathers.

Ojibwe understanding of kinship is complex and includes the immediate family as well as extended family. It is considered a modifiedbifurcate mergingkinship system.As with any bifurcate-merging kinship system, siblings generally share the same kinship term withparallel cousinsbecause they are all part of the same clan. The modified system allows for younger siblings to share the same kinship term with younger cross-cousins. Complexity wanes further from the person's immediate generation, but some complexity is retained with female relatives. For example,ninooshenhis "my mother's sister" or "my father's sister-in-law" – i.e., my parallel-aunt, but also "my parent's female cross-cousin". Great-grandparents and older generations, as well as great-grandchildren and younger generations, are collectively calledaanikoobijigan.This system of kinship reflects the Anishinaabe philosophy of interconnectedness and balance among all living generations, as well as of all generations of the past and of the future.

The Ojibwe people were divided into a number ofdoodemag(clans; singular:doodem) named primarily for animals and birdstotems(pronounceddoodem). The word in the Ojibwe language means "my fellow clansman."[31]The five original totems wereWawaazisii(Bullhead),Baswenaazhi/ "Ajiijaak" ( "Echo-maker", i.e., Crane),Aan'aawenh(Pintail Duck),Nooke( "Tender", i.e., Bear) andMoozwaanowe( "Little" Moose-tail). The Crane totem was the most vocal among the Ojibwe, and the Bear was the largest – so large, that it was sub-divided into body parts such as the head, the ribs and the feet. Each clan had certain responsibilities among the people. People had to marry a spouse from a different clan.

Traditionally, each band had a self-regulating council consisting of leaders of the communities' clans, orodoodemaan.The band was often identified by the principaldoodem.In meeting others, the traditional greeting among the Ojibwe people is, "What is your 'doodem'?" ( "Aaniin gidoodem?"or"Awanen gidoodem?") The response allows the parties to establish social conduct by identifying as family, friends or enemies. Today, the greeting has been shortened to"Aanii"(pronounced "Ah-nee" ).[32]

Spiritual beliefs

[edit]

The Ojibwe have spiritual beliefs that have been passed down byoral traditionunder the Midewiwin teachings. These include acreation storyand a recounting of the origins of ceremonies and rituals. Spiritual beliefs and rituals were very important to the Ojibwe because spirits guided them through life. Birch bark scrolls and petroforms were used to pass along knowledge and information, as well as for ceremonies. Pictographs were also used for ceremonies.

Thesweatlodgeis still used during important ceremonies about the four directions, when oral history is recounted. Teaching lodges are common today to teach the next generations about the language and ancient ways of the past. The traditional ways, ideas, and teachings are preserved and practiced in such living ceremonies.

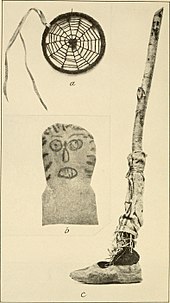

The moderndreamcatcher,adopted by thePan-Indian MovementandNew Agegroups, originated in the Ojibwe "spider web charm",[33]a hoop with woven string or sinew meant to replicate a spider's web, used as a protective charm for infants.[34]According to Ojibwe legend, the protective charms originate with theSpider Woman,known asAsibikaashi;who takes care of the children and the people on the land and as the Ojibwe Nation spread to the corners of North America it became difficult for Asibikaashi to reach all the children, so the mothers and grandmothers wove webs for the children, which had anapotropaicpurpose and were not explicitly connected with dreams.[34]

Funeral practices

[edit]Traditional

[edit]In Ojibwe tradition, the main task after a death is to bury the body as soon as possible, the very next day or even on the day of death. This was important because it allowed the spirit of the dead to journey to its place of joy and happiness. The land of happiness where the dead reside is calledGaagige Minawaanigozigiwining.[35]This was a journey that took four days. If burial preparations could not be completed the day of the death, guests and medicine men were required to stay with the deceased and the family in order to help mourn, while also singing songs and dancing throughout the night. Once preparations were complete, the body would be placed in an inflexed position with their knees towards their chest.[36]Over the course of the four days it takes the spirit to journey to its place of joy, it is customary to have food kept alongside the grave at all times. A fire is set when the sun sets and is kept going throughout the night. The food is to help feed the spirit over the course of the journey, while the smoke from the fire is a directional guide. Once the four–day journey is over, a feast is held, which is led by the chiefmedicine man.At the feast, it is the chief medicine man's duty to give away certain belongings of the deceased. Those who were chosen to receive items from the deceased are required to trade in a new piece of clothing, all of which would be turned into a bundle. The bundle of new cloths and a dish is then given to the closest relative. The recipient of the bundle must then find individuals that he or she believes to be worthy, and pass on one of the new pieces of clothing.[37]

Contemporary

[edit]According to Lee Staples, an Ojibwe spiritual leader from the Mille Lacs Indian Reservation, present day practices follow the same spiritual beliefs and remain fairly similar. When an individual dies, a fire is lit in the home of the family, who are also expected to continuously maintain the fire for four days. Over the four days, food is also offered to the spirit. Added to food offerings, tobacco is also offered as it is considered one of four sacred medicines traditionally used by Ojibwe communities. On the last night of food offerings, a feast is also held by the relatives which ends with a final smoke of the offering tobacco or the tobacco being thrown in the fire. Although conventional caskets are mainly used in today's communities, birch bark fire matches are buried along with the body as a tool to help light fires to guide their journey toGaagige Minawaanigozigiwining.[35]

Ethnobotany

[edit]This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(August 2013) |

Plants used by the Ojibwe includeAgrimonia gryposepala,used for urinary problems,[38]andPinus strobus,the resin of which was used to treat infections andgangrene.The roots ofSymphyotrichum novae-angliaeare smoked in pipes to attract game.[39]Allium tricoccumis eaten as part of Ojibwe cuisine.[40]They also use adecoctionas a quick-actingemetic.[41]Aninfusionof thealbasubspecies ofSilene latifoliais used asphysic.[42]The South Ojibwa use a decoction of the rootViola canadensisfor pains near the bladder.[43]The Ojibwa are documented to use the root ofUvularia grandiflorafor pain in thesolar plexus,which may refer topleurisy.[44]They take a compound decoction of the root ofRibes glandulosumfor back pain and for "female weakness".[45]

The Ojibwe eat the corms ofSagittaria cuneatafor indigestion, and also as a food, eaten boiled fresh, dried or candied with maple sugar. Muskrat and beavers store them in large caches, which they have learned to recognize and appropriate.[46]They take an infusion of theAntennaria howelliissp.neodioicaafter childbirth to purge afterbirth and to heal.[47]They use the roots ofSolidago rigida,using a decoction of root as an enema and take an infusion of the root for "stoppage of urine".[48]They useAbies balsamea;melting the gum on warm stones and inhaling the fumes for headache.[49]They also use adecoctionof the root as an herbal steam for rheumatic joints.[49]They also combine the gum with bear grease and use it as an ointment for hair.[50]They use the needle-like leaves in as part of ceremony involving the sweatbath, and use the gum for colds and inhale the leaf smoke for colds.[51]They use the plant as a cough medicine.[52]The gum is used for sores and a compound containing leaves is used as wash. The liquid balsam from bark blisters is used for sore eyes.[51]They boil the resin twice and add it to suet or fat to make a canoe pitch.[53]The bark gum is taken for chest soreness from colds, applied to cuts and sores, and decoction of the bark is used to induce sweating. The bark gum is also taken forgonorrhea.[54]A decoction (tea) of powdered, driedOnoclea sensibilisroot is used to stimulate milk flow in female patients.[55]

Bands

[edit]In hisHistory of the Ojibway People(1855),William W. Warrenrecorded 10 major divisions of the Ojibwe in the United States. He mistakenly omitted the Ojibwe located in Michigan, western Minnesota and westward, and all of Canada. When identified major historical bands located in Michigan and Ontario are added, the count becomes 15:[citation needed]

| English Name | Ojibwe Name (in double-vowel spelling) |

Location |

|---|---|---|

| Saulteaux | Baawitigowininiwag | Sault Ste. Mariearea ofOntarioandMichigan |

| Border-Sitters | Biitan-akiing-enabijig | St. Croix-Namekagon River valleys in eastern Minnesota and northern Wisconsin |

| Lake Superior Band | Gichi-gamiwininiwag | south shore of Lake Superior |

| Mississippi River Band | Gichi-ziibiwininiwag | upper Mississippi River inMinnesota |

| Rainy Lake Band | Goojijiwininiwag | Rainy LakeandRiver,about the northern boundary of Minnesota |

| Ricing-Rails | Manoominikeshiinyag | along headwaters ofSt. Croix Riverin Wisconsin and Minnesota |

| Pillagers | Makandwewininiwag | North-central Minnesota and Mississippi River headwaters |

| Mississaugas | Misi-zaagiwininiwag | north ofLake Erie,extending north of Lake Huron about the Mississaugi River |

| Dokis Band (Dokis's and Restoule's bands) | — | AlongFrench River (Wemitigoj-Sibi)region (includingLittle French River (Ziibiins)andRestoule River) in Ontario, near Lake Nipissing |

| Ottawa Lake (Lac Courte Oreilles) Band | Odaawaa-zaaga'iganiwininiwag | Lac Courte Oreilles,Wisconsin |

| Bois Forte Band | Zagaakwaandagowininiwag | north of Lake Superior |

| Lac du Flambeau Band | Waaswaaganiwininiwag | head ofWisconsin River |

| Muskrat Portage Band | Wazhashk-Onigamininiwag | northwest side of Lake Superior at the Canada–US border |

| Nopeming Band | Noopiming Azhe-ininiwag | northeast of Lake Superior and west of Lake Nipissing |

Numerous Ojibwe First Nations, tribes, and bands exist today in Canada and the United States.[citation needed]See also the listing ofSaulteaux communities.

- Aamjiwnaang First Nation

- Aroland First Nation

- Batchewana First Nation

- Bay Mills Indian Community

- Biinjitiwabik Zaaging Anishnabek First Nation

- Burt Lake Band of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians

- Caldwell First Nation

- Chapleau Ojibway First Nation

- Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point

- Chippewas of Lake Simcoe and Huron (Historical)

- Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation

- Chippewa of the Thames First Nation

- Chippewas of Saugeen Ojibway Territory,historical

- Chippewa CreeTribe ofRocky Boys Indian Reservation

- Curve Lake First Nation

- Cutler First Nation

- Dokis First Nation

- Eabametoong First Nation

- Fort William First Nation

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

- Garden River First Nation

- Henvey Inlet First Nation

- Grassy Narrows First Nation (Asabiinyashkosiwagong Nitam-Anishinaabeg)

- Islands in the Trent Waters

- Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation(also known asRiding Mountain Band)

- Koocheching First Nation

- Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation

- Lac La Croix First Nation

- Lac Seul First Nation

- Lake Nipigon Ojibway First Nation

- Lake Superior Chippewa Tribe

- Bad River Chippewa Band

- Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Keweenaw Bay Indian Community

- L'Anse Band of Chippewa Indians

- Ontonagon Band of Chippewa Indians

- Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

- Bois Brule River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Chippewa River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

- Removable St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Sokaogon Chippewa Community

- St. Croix Chippewa Indiansof Wisconsin

- Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians,Michigan

- Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians

- Magnetawan First Nation,Ontario

- Minnesota Chippewa Tribe,Minnesota

- Bois Forte Band of Chippewa

- Bois Forte Band of Chippewa

- Lake Vermilion Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Little Forks Band of Rainy River Saulteaux

- Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Grand Portage Band of Chippewa

- Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe

- Cass Lake Band of Chippewa

- Lake Winnibigoshish Band of Chippewa

- Leech Lake Band of Pillagers

- Removable Lake Superior Bands of Chippewa of the Chippewa Reservation

- White Oak Point Band ofMississippi Chippewa

- Pokegama Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Removable Sandy Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe,Minnesota

- Mille Lacs Indians

- Sandy Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Rice Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- St. Croix Band of Chippewa Indians of Minnesota

- Kettle River Band of Chippewa Indians

- Snake and Knife Rivers Band of Chippewa Indians

- White Earth Band of Chippewa

- Gull Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Otter Tail Band of Pillagers

- Rabbit Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Removable Mille Lacs Indians

- Rice Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Bois Forte Band of Chippewa

- Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation,previously Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation

- Mississaugi First Nation,Ontario

- North Caribou Lake First Nation,Ontario

- Ojibway Nation of Saugeen First Nation,Ontario

- Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation,Ontario

- Osnaburg House Band of Ojibway and Cree (Historical)

- Cat Lake First Nation,Ontario

- Mishkeegogamang First Nation(formerly known asNew Osnaburgh First Nation)

- Slate Falls First Nation

- Pembina Band of Chippewa Indians(Historical)

- Pikangikum First Nation

- Poplar Hill First Nation

- Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians

- Lac des Bois Band of Chippewa Indians

- Rolling River First Nation

- Sagamok Anishnawbek First Nation

- Saginaw Chippewa Tribal Council

- Sagkeeng First Nation

- Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians

- SaulteauxFirst Nation

- Shawanaga First Nation

- Southeast Tribal Council

- Berens River First Nation

- Bloodvein First Nation

- Brokenhead First Nation

- Buffalo Point First Nation (Saulteaux)

- Hollow Water First Nation

- Black River First Nation

- Little Grand Rapids First Nation

- Pauingassi First Nation (Saulteaux)

- Poplar River First Nation

- Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians

- Wabaseemoong Independent Nation

- Wabauskang First Nation

- Wabun Tribal Council

- Beaverhouse First Nation

- Brunswick House First Nation

- Chapleau Ojibwe First Nation

- Matachewan First Nation

- Mattagami First Nation

- Wahgoshig First Nation

- Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation

- Wahnapitae First Nation

- Walpole Island First Nation

- Washagamis Bay First Nation

- Whitefish Bay First Nation

- Whitefish Lake First Nation

- Whitefish River First Nation

- Whitesand First Nation

- Whitewater Lake First Nation

- Wikwemikong Unceded First Nation

Notable historical Ojibwe people

[edit]Ojibwe people from the 20th and 21st centuries should be listed under their specific tribes.

- Francis Assikinack(1824–1863), historian fromManitoulin Island

- Stephen Bonga,Ojibwe/African-American fur trader and interpreter[56]

- George Bonga(1802–1880), Ojibwe/African-American fur trader and interpreter

- Jeanne L'Strange Cappel(1873–1949), writer, teacher and clubwoman

- Hanging Cloud,19th c.Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwewoman warrior

- George Copway(1818–1869), missionary and writer

- Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom(c. 1797–1880), Ojibwe-African American woman in the early Methodist Episcopal Church in Minnesota

- Fr.Philip B. Gordon(1885–1948),Roman Catholic priestand activist fromGordon, Wisconsin

- Hole in the Day(1825–1868), Chief of theMississippi Bandof theMinnesotaOjibwe

- Peter Jones(1802–1856),Mississaugamissionary and writer

- Kechewaishke(Gichi-Weshkiinh, Buffalo) (ca. 1759–1855), chief

- Edmonia Lewis(ca. 1844–1907),MississaugaOjibwe/African-American sculptor

- Maungwudaus,(1811–1888), performer, interpreter, mission worker, and herbalist

- Medweganoonind,19th-centuryRed Lake Ojibwechief

- Ozaawindib(Yellow Head), early 19th c. nonbinary warrior, guide

- Chief Rocky Boy(fl. late 19th c.), chief

- Jane Johnston Schoolcraft(1800–1842), author, wife ofHenry Rowe Schoolcraft,born in Sault Ste. Marie

- John Smith(ca. 1824–1922, chief, from Cass Lake, Minnesota

- Alfred Michael "Chief" Venne(1879–1971), athletic manager and coach from Leroy, North Dakota

- Waabaanakwad(White Cloud) (ca. 1830–1898), Gull Lake chief

- William Whipple Warren(1825–1853), first historical writer of the Ojibwe people, territorial legislator

- Zheewegonab(fl. 1780–1805), band leader among the northern Ojibwe

Ojibwe treaties

[edit]

- Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority– 1836CT fisheries

- Grand Council of Treaty 3– Treaty 3

- Grand Council of Treaty 8– Treaty 8

- Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission– 1837CT, 1836CT, 1842CT and 1854CT

- Nishnawbe Aski Nation– Treaty 5 and Treaty 9

- Red Lake Band of Chippewa– 1886CT and 1889CT

- Union of Ontario Indians– RS, RH1, RH2, misc. pre-confederation treaties

- Treaties with France

- Treaties with Great Britain and the United Kingdom

- Treaty of Fort Niagara (1764)

- Treaty of Fort Niagara (1781)

- Indian Officers' Land Treaty (1783)

- The Crawford Purchases (1783)

- Between the Lakes Purchase (1784)

- Treaty of Peace with Sioux, Chippewa and Winnebago (1787)

- Toronto Purchase(1787)

- Indenture to the Toronto Purchase (1805)

- The McKee Purchase (1790)

- Between the Lakes Purchase (1792)

- Chenail Ecarte (Sombra Township) Purchase (1796)

- London Township Purchase (1796)

- Land for Joseph Brant (1797)

- Penetanguishene Bay Purchase(1798)

- St. Joseph Island (1798)

- Head-of-the-Lake Purchase (1806)

- Lake Simcoe-Lake Huron Purchase(1815)

- Lake Simcoe-Nottawasaga Purchase (1818)

- Ajetance Purchase (1818)

- Rice Lake Purchase (1818)

- The Rideau Purchase (1819)

- Long Woods Purchase (1822)

- Huron TractPurchase (1827)

- Saugeen Tract Agreement(1836)

- Manitoulin Agreement (1836)

- TheRobinson Treaties

- Manitoulin Island Treaty (1862)

- Treaties with Canada

- Treaty No. 1(1871) – Stone Fort Treaty

- Treaty No. 2(1871)

- Treaty No. 3(1873) –Northwest AngleTreaty

- Treaty No. 4(1874) – Qu'Appelle Treaty

- Treaty No. 5(1875)

- Treaty No. 6(1876)

- Treaty No. 8(1899)

- Treaty No. 9(1905–1906) –James BayTreaty

- Treaty No. 5, Adhesions (1908–1910)

- TheWilliams Treaties(1923)

- Treaty No. 9, Adhesions (1929–1930)

- Treaties with the United States

- Treaty of Fort McIntosh(1785)

- Treaty of Fort Harmar(1789)

- Treaty of Greenville(1795)

- Fort Industry(1805)

- Treaty of Detroit(1807)

- Treaty of Brownstown(1808)

- Treaty of Springwells(1815)

- Treaty of St. Louis (1816)– Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi

- Treaty of Miami Rapids(1817)

- Treaty of St. Mary's(1818)

- Treaty of Saginaw(1819)

- Treaty of Saúlt Ste. Marie(1820)

- Treaty of L'Arbre Croche and Michilimackinac(1820)

- Treaty of Chicago(1821)

- First Treaty of Prairie du Chien(1825)

- Treaty of Fond du Lac(1826)

- Treaty of Butte des Morts(1827)

- Treaty of Green Bay(1828)

- Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien(1829)

- Treaty of Chicago(1833)

- Treaty of Washington (1836)– Ottawa & Chippewa

- Treaty of Washington (1836) – Swan Creek & Black River Bands

- Treaty of Detroit(1837)

- Treaty of St. Peters(1837) – White Pine Treaty

- Treaty of Flint River(1837)

- Saganaw Treaties

- Treaty of Saganaw(1838)

- Supplemental Treaty(1839)

- Treaty of La Pointe(1842) – Copper Treaty

- Isle Royale Agreement(1844)

- Treaty of Potawatomi Creek(1846)

- Treaty of Fond du Lac(1847)

- Treaty of Leech Lake(1847)

- Treaty of La Pointe(1854)

- Treaty of Washington (1855)

- Treaty of Detroit (1855)– Ottawa & Chippewa

- Treaty of Detroit (1855)– Sault Ste. Marie Band

- Treaty of Detroit (1855)– Swan Creek & Black River Bands

- Treaty of Sac and Fox Agency(1859)

- Treaty of Washington (1863)

- Treaty of Old Crossing (1863)

- Treaty of Old Crossing (1864)

- Treaty of Washington (1864)

- Treaty of Isabella Reservation (1864)

- Treaty of Washington (1866)

- Treaty of Washington (1867)

Gallery

[edit]-

A-na-cam-e-gish-ca(Aanakamigishkaang/ "[Traces of] Foot Prints [upon the Ground]" ), Ojibwe chief, fromHistory of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

Bust ofAysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay(Eshkibagikoonzheor "Flat Mouth" ), a Leech Lake Ojibwe chief

-

ChiefBeautifying Bird(Nenaa'angebi), by Benjamin Armstrong, 1891

-

Bust ofBeshekee,war chief, modeled 1855, carved 1856

-

Caa-tou-see,an Ojibwe, fromHistory of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

Hanging Cloud,The female Ojibwe warrior the newspapers called the Chippewa Warrior Princess

-

Jack-O-Pa(Zhaagobe/ "Six" ), aSt. Croix Ojibwechief, fromHistory of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

Kay be sen day way We Win,byEastman Johnson,1857

-

Kei-a-gis-gis, a Plains Ojibwe woman, painted byGeorge Catlin

-

Leech Lake Ojibwe delegation to Washington, 1899

-

Chippewa baby teething on "Indians at Work" magazine while strapped to a cradleboard at a rice lake in 1940.

-

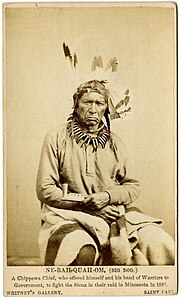

Chippewa Chief Ne-bah-quah-om (Big Dog) offered to fight the Sioux for the government in 1862

-

"One Called From A Distance" (Midwewinind) of theWhite Earth Band,1894.

-

Pee-Che-Kir,Ojibwe chief, painted byThomas Loraine McKenney,1843

-

Ojibwe chiefRocky Boy

-

Ojibwe woman and child, fromHistory of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

Tshusick,an Ojibwe woman, fromHistory of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

Chief medicine man Axel Pasey and family at Grand Portage Minnesota.

-

Historic 1849 petition of Ojibwe chiefs

-

Wells American Indian picture writing

-

Wildfire, English nameEdmonia Lewis

-

Aamoons,chief of La Flambeau band, photographedc. 1862,possibly in Washington, D.C.

-

Details ofOjibwe Wigwam at Grand PortagebyEastman Johnson,c. 1906

-

Vintagestereoscopicphoto entitled "Chippewa lodges, Beaver Bay, by Childs, B. F."

-

Pictographs on Mazinaw Rock,Bon Echo Provincial Park,Ontario

-

Ojibwe hunter in winter 1908

-

Camp fire Chippewa village Itasca State Park Minnesota 1926

-

Medicine man from Cass Lake 1911

-

An Ojibwa woman and child, Red River Settlement, Manitoba, 1895

-

Ojibwa village

-

Minnesota Ojibwa 1910

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ab"CDC – American – Indian – Alaska – Native – Populations – Racial – Ethnic – Minorities – Minority Health".2 December 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2012.

- ^abc"Ojibwe | The Canadian Encyclopedia".thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.Retrieved2021-01-31.

- ^abJelsing, Kaden Mark (2023).Sovereign Futures: Indigenous and Settler Prophecies in Two Nineteenth-Century American "Northwests"(Doctor of Philosophy thesis).University of British Columbia.p. 57.ᐅᒋᐻᐘᑭ

- ^Spencer, Kelly (August 31, 2020)."The rock carvings of Kinoomaagewaabkong".Norfolk & Tillsonburg News.RetrievedJanuary 31,2021.

- ^"BEACH HOUSE – MYTH".YouTube.Archived fromthe originalon 2018-06-30.

- ^Redix, Erik M. (October 8, 2018)."Maple sugaring's roots with the Ojibwe people run deep".MinnPost.RetrievedJune 10,2023.

- ^"Anishinabe".eMuseum @ Minnesota State University.Minnesota State University. Mankato. Archived fromthe originalon 2010-04-09.Retrieved2010-03-16.

- ^Activity 1. Introduction to Anishinabe/Ojibwe/Chippewa, Anishinabe/Ojibwe/Chippewa: Culture of an Indian Nation lesson plan, National Endowment for the Humanities, 2023, 400 7th Street SW., Washington, DC[1]

- ^"Batchewana – History".batchewana.ca.Retrieved2021-01-31.

- ^"Microsoft Word – dictionary best for printing 2004 ever finalpdf.doc"(PDF).Retrieved2011-01-02.

- ^Warren, William W. (1984) [1885].History of the Ojibway People.Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 36.ISBN0-87351-162-X.

- ^Louise Erdrich,Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country(2003)ArchivedSeptember 26, 2007, at theWayback Machine

- ^Johnston, Basil. (2007)Anishinaubae ThesaurusISBN0-87013-753-0

- ^Three Fires Unity: The Anishnaabeg of the Lake Huron Borderlands.Phil Bellfy. 2011. University of Nebraska.

- ^"First Nations Culture Areas Index".the Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- ^"Anishinaabemowin: Ojibwe Language | The Canadian Encyclopedia".thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.Retrieved2021-01-31.

- ^Roy, Loriene."Ojibwa".Countries and Their Cultures.Retrieved9 August2016.

- ^Anthony, David.The Horse, the Wheel and Language,Princeton University Press,2007, p. 102

- ^"Conversations on Reconciliation:" Tiotiá:ke and Mooniyaang: Land Acknowledgement. "".Onishka.Montréal. 6 June 2017. Archived fromthe originalon 4 June 2021.Retrieved7 March2021– via Indigenous Contemporary Scene.

- ^Schmalz, Peter (May 1992)."The Ojibwa of southern Ontario".Histoire Sociale / Social History.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^"The Atlas of Canada: Historical Indian Treaties".RetrievedMarch 1,2018.

- ^Gevinson, Alan."Which Native American Tribes Allied Themselves with the French?".teachinghistory.org.Retrieved23 September2011.

- ^James A. Clifton, "Wisconsin Death March: Explaining the Extremes in Old Northwest Indian Removal",inTransactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters,1987, 5:1–40, accessed 2 March 2010

- ^"Treaty Between the Ottawa, Chippewa, Wyandot, and Potawatomi Indians".World Digital Library.1807-11-17.Retrieved2013-08-03.

- ^Johnson, Michael G. (2016).Ojibwa People of Forests and Prairies.Firefly Books.

- ^"In tribes across Minnesota, indigenous food movement takes root".Star Tribune.23 July 2018.

- ^"Eating indigenously changes diets and lives of Native Americans".

- ^"Anishinabe".

- ^Child, Brenda J. (2012).Holding Our World Together: Ojibwe Women and the Survival of Community.Penguin.ISBN9781101560259.

- ^"Ojibwe Culture"Archived2015-06-23 at theWayback Machine,Milwaukee Public Museum, accessed 10 December 2011

- ^Billard, Jules B. (1989). "N. Scott Momaday" I am Alive... "".The World of the American Indian, A volume in the Story of Man Library.Washington, D.C.:National Geographic Society.p. 13.ISBN0-87044-799-8.

- ^Team, Forvo."Aanii pronunciation: How to pronounce Aanii in Ojibwa".Forvo.Retrieved2021-03-07.

- ^Jim Great Elk Waters (2002),View from the Medicine Lodge,Seven Locks Press, p. 111.

- ^abDensmore 1970,p. 113.

- ^abAllis, Ellary. "The Spirit of The Dead According To Ojibwe Beliefs."SevenPonds,Seven Ponds, 8 Dec. 2016, blog.sevenponds /cultural-perspectives/the-spirit-of-the-dead-according-to-ojibwe-beliefs.

- ^Hilger, M. Inez (1944), Chippewa Burial and Mourning Customs. American Anthropologist, 46: 564–568.doi:10.1525/aa.1944.46.4.02a00240

- ^James A. Clifton, "Wisconsin Death March: Explaining the Extremes in Old Northwest Indian Removal", inTransactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters,1987, 5:1–40

- ^Daniel E. Moerman (2009).Native American Medicinal Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary.Timber Press. pp.52–53.ISBN978-0-88192-987-4.

- ^Densmore, Frances 1928 Uses of Plants by the Chippewa Indians. SI-BAE Annual Report #44:273–379 (p. 376)

- ^Smith 1932,p. 104.

- ^Densmore, Frances 1928 Uses of Plants by the Chippewa Indians. SI-BAE Annual Report #44:273–379 (p. 346)

- ^Smith 1932,p. 361.

- ^Hoffman, W.J., 1891, The Midewiwin or 'Grand Medicine Society' of the Ojibwa, SI-BAE Annual Report #7, p. 201

- ^Smith, Huron H., 1932, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians, Bulletin of the Public Museum of Milwaukee 4:327–525, p. 374

- ^Densmore, Frances 1928 Uses of Plants by the Chippewa Indians. SI-BAE Annual Report #44:273–379 (p. 356)

- ^Smith 1932,p. 396.

- ^Smith 1932,p. 363.

- ^Densmore, Frances, 1928, Uses of Plants by the Chippewa Indians, SI-BAE Annual Report #44:273–379, p. 348 (Note: This source comes from the Native American ethnobotany database <http://naeb.brit.org/> which lists the plant as Oligoneuron rigidum var. rigidum). Accessed 19 January 2018

- ^abDensmore, Frances, 1928, Uses of Plants by the Chippewa Indians, SI-BAE Annual Report #44:273–379, p. 338

- ^Densmore, Frances, 1928, Uses of Plants by the Chippewa Indians, SI-BAE Annual Report #44:273–379, p. 350

- ^abSmith, Huron H., 1932, Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians, Bulletin of the Public Museum of Milwaukee 4:327–525, p. 378

- ^Reagan, Albert B., 1928, Plants Used by the Bois Fort Chippewa (Ojibwa) Indians of Minnesota, Wisconsin Archeologist 7(4):230–248, p. 244

- ^Smith 1932,p. 420.

- ^Hoffman, W.J., 1891, The Midewiwin or 'Grand Medicine Society' of the Ojibwa, SI-BAE Annual Report #7, p. 198

- ^Smith 1932,p. 382.

- ^"Portrait of Stephen Bonga",Wisconsin Historical Images, accessed 23 January 2014

Bibliography

[edit]- Densmore, Frances (1970) [1929].Chippewa Customs.Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- H. Hickerson,The Chippewa and Their Neighbors(1970)

- R. Landes,Ojibwa Sociology(1937, repr. 1969)

- R. Landes,Ojibwa Woman(1938, repr. 1971)

- Smith, Huron H. (1932). "Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians".Bulletin of the Public Museum of Milwaukee(4): 327–525.

- F. Symington,The Canadian Indian(1969)

Further reading

[edit]- Aaniin Ekidong: Ojibwe Vocabulary Project. St. Paul: Minnesota Humanities Center, 2009

- Baker, Jocelyn (1936). "Ojibwa of the Lake of the Woods".Canadian Geographic Journal.12(1): 47–54.

- Bento-Banai, Edward (2004). Creation- From the Ojibwa. The Mishomis Book.

- Child, Brenda J. (2014).My Grandfather's Knocking Sticks: Ojibwe Family Life and Labor on the Reservation.St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- Danziger, E.J. Jr. (1978).The Chippewa of Lake Superior.Norman:University of Oklahoma Press.

- Denial, Catherine J. (2013).Making Marriage: Husbands, Wives, and the American State in Dakota and Ojibwe Country.St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- Densmore, F. (1979).Chippewa customs.St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. (Published originally 1929)

- Grim, J.A. (1983).The shaman: Patterns of religious healing among the Ojibway Indians.Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Gross, L.W. (2002).The comic vision of Anishinaabe culture and religion.American Indian Quarterly, 26, 436–459.

- Howse, Joseph.A Grammar of the Cree Language; With which is combined an analysis of the Chippeway dialect.London: J.G.F. & J. Rivington, 1844.

- Johnston, B. (1976).Ojibway heritage.Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- Long, J.Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader Describing the Manners and Customs of the North American Indians, with an Account of the Posts Situated on the River Saint Laurence, Lake Ontario, & C., to Which Is Added a Vocabulary of the Chippeway Language... a List of Words in the Iroquois, Mehegan, Shawanee, and Esquimeaux Tongues, and a Table, Shewing the Analogy between the Algonkin and the Chippeway Languages.London: Robson, 1791.

- Nichols, J.D., & Nyholm, E. (1995).A concise dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Treuer, Anton.Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask.St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

- Treuer, Anton.The Assassination of Hole in the Day.St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2011.

- Treuer, Anton. Ojibwe in Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2010.Ojibwe in Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

- Treuer, Anton. Living Our Language: Ojibwe Tales & Oral Histories. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

- Vizenor, G. (1972).The everlasting sky: New voices from the people named the Chippewa.New York: Crowell-Collier Press.

- Vizenor, G. (1981).Summer in the spring: Ojibwe lyric poems and tribal stories.Minneapolis: The Nodin Press.

- Vizenor, G. (1984).The people named the Chippewa: Narrative histories.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Warren, William W. (1851).History of the Ojibway People.

- White, Richard (1991).The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815(Studies in North American Indian History) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

- White, Richard (July 31, 2000). Chippewas of the Sault. The Sault Tribe News.

- Wub-e-ke-niew. (1995).We have the right to exist: A translation of aboriginal indigenous thought.New York: Black Thistle Press.

External links

[edit]- Ojibwe Song Pictures,recorded by Frances Desmore

- Ojibwe People's Dictionary

- Ojibwe Waasa-Inaabidaa–PBSdocumentary featuring the history and culture of the Anishinaabe-Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes (United States-focused).

- Ojibwe migratory mapfrom Ojibwe Waasa-Inaabidaa

- Batchewana First Nation

- Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Mississaugi First Nation

- Southeast Tribal Council

- Wabun Tribal Council

- Ojibwe Stories: Gaganoonididaafrom thePublic Radio Exchange

- Ojibwe Astronomy

- Ojibwe

- Algonquian ethnonyms

- Algonquian peoples

- Anishinaabe groups

- Anishinaabe lands

- First Nations in Alberta

- First Nations in Manitoba

- First Nations in Ontario

- First Nations in Quebec

- First Nations in Saskatchewan

- Great Lakes tribes

- Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands

- Native American tribes in Michigan

- Native American tribes in Minnesota

- Native American tribes in Montana

- Native American tribes in North Dakota

- Native American tribes in Wisconsin

- Native American tribes

- Plains tribes

- Upper Peninsula of Michigan

![A-na-cam-e-gish-ca (Aanakamigishkaang/"[Traces of] Foot Prints [upon the Ground]"), Ojibwe chief, from History of the Indian Tribes of North America](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/A-na-cam-e-gish-ca.jpg/180px-A-na-cam-e-gish-ca.jpg)