Old Chinese

| Old Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

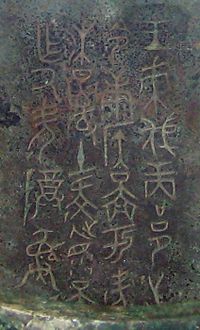

Inscription on theKang Hougui(late 11th century BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native to | Ancient China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Era | Late Shang,Zhou,Warring States period,Qin,Han[a] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sino-Tibetan

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oracle bone script Bronze script Seal script Bird-worm seal script | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language codes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-3 | och | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

och | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glottolog | shan1294Shanggu Hanyu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Thượng cổ Hán ngữ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Thượng cổ Hán ngữ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Old Chinese,also calledArchaic Chinesein older works, is the oldest attested stage ofChinese,and the ancestor of all modernvarieties of Chinese.[a]The earliest examples of Chinese are divinatory inscriptions onoracle bonesfrom around 1250 BC, in theLate Shangperiod.Bronze inscriptionsbecame plentiful during the followingZhou dynasty.The latter part of the Zhou period saw a flowering of literature, includingclassical workssuch as theAnalects,theMencius,and theZuo Zhuan.These works served as models for Literary Chinese (orClassical Chinese), which remained the written standard until the early twentieth century, thus preserving the vocabulary and grammar of late Old Chinese.

Old Chinese was written with several early forms ofChinese characters,includingoracle bone,bronze,andseal scripts.Throughout the Old Chinese period, there was a close correspondence between a character and a monosyllabic and monomorphemic word. Although the script is not Alpha betic, the majority of characters were created based on phonetic considerations. At first, words that were difficult to represent visually were written using a "borrowed" character for a similar-sounding word (rebus principle). Later on, to reduce ambiguity, new characters were created for these phonetic borrowings by appending aradicalthat conveys a broad semantic category, resulting in compoundXing sheng(phono-semantic) characters (Hình thanh tự). For the earliest attested stage of Old Chinese of the late Shang dynasty, the phonetic information implicit in theseXing shengcharacters which are grouped into phonetic series, known as thexieshengseries,represents the only direct source of phonological data for reconstructing the language. The corpus ofXing shengcharacters was greatly expanded in the following Zhou dynasty. In addition, the rhymes of the earliest recorded poems, primarily those of theClassic of Poetry,provide an extensive source of phonological information with respect to syllable finals for the Central Plains dialects during theWestern ZhouandSpring and Autumn periods.Similarly, theChu Ciprovides rhyme data for the dialect spoken in theChuregion during theWarring States period.These rhymes, together with clues from the phonetic components ofXing shengcharacters, allow most characters attested in Old Chinese to be assigned to one of 30 or 31 rhyme groups. For late Old Chinese of the Han period, the modernSouthern Minlanguages, the oldest layer ofSino-Vietnamese vocabulary,and a few early transliterations of foreign proper names, as well as names for non-native flora and fauna, also provide insights into language reconstruction.

Although many of the finer details remain unclear, most scholars agree that Old Chinese differed fromMiddle Chinesein lackingretroflexandpalatalobstruentsbut having initialconsonant clustersof some sort, and in having voicelessnasalsandliquids.Most recent reconstructions also describe Old Chinese as a language without tones, but having consonant clusters at the end of the syllable, whichdevelopedintotonedistinctions in Middle Chinese.

Most researchers trace the core vocabulary of Old Chinese toSino-Tibetan,with much early borrowing from neighbouring languages. During the Zhou period, the originally monosyllabic vocabulary was augmented with polysyllabic words formed bycompoundingandreduplication,although monosyllabic vocabulary was still predominant. Unlike Middle Chinese and the modern Chinese languages, Old Chinese had a significant amount of derivational morphology. Severalaffixeshave been identified, including ones for the verbification of nouns, conversion between transitive and intransitive verbs, and formation of causative verbs.[3]Like modern Chinese, it appears to be uninflected, though a pronoun case and number system seems to have existed during the Shang and early Zhou but was already in the process of disappearing by the Classical period.[4]Likewise, by the Classical period, most morphological derivations had become unproductive or vestigial, and grammatical relationships were primarily indicated using word order andgrammatical particles.

Classification[edit]

Middle Chinese and its southern neighboursKra–Dai,Hmong–Mienand theVieticbranch ofAustroasiatichave similar tone systems, syllable structure, grammatical features and lack of inflection, but these are believed to beareal featuresspread by diffusion rather than indicating common descent.[5][6] The most widely accepted hypothesis is that Chinese belongs to theSino-Tibetan language family,together withBurmese,Tibetanand many other languages spoken in theHimalayasand theSoutheast Asian Massif.[7] The evidence consists of some hundreds of proposed cognate words,[8]including such basic vocabulary as the following:[9]

| Meaning | Old Chinese[b] | Old Tibetan | Old Burmese |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'I' | Ngô*ŋa[11] | ṅa[12] | ṅā[12] |

| 'you' | Nhữ*njaʔ[13] | naṅ[14] | |

| 'not' | Vô*mja[15] | ma[12] | ma[12] |

| 'two' | Nhị*njijs[16] | gñis[17] | nhac<*nhik[17] |

| 'three' | Tam*sum[18] | gsum[19] | sumḥ[19] |

| 'five' | Năm*ŋaʔ[20] | lṅa[12] | ṅāḥ[12] |

| 'six' | Sáu*C-rjuk[c][22] | drug[19] | khrok<*khruk[19] |

| 'sun' | Ngày*njit[23] | ñi-ma[24] | niy[24] |

| 'name' | Danh*mjeŋ[25] | myiṅ<*myeŋ[26] | maññ < *miŋ[26] |

| 'ear' | Nhĩ*njəʔ[27] | rna[28] | nāḥ[28] |

| 'joint' | Tiết*tsik[29] | tshigs[24] | chac<*chik[24] |

| 'fish' | Cá*ŋja[30] | ña<*ṅʲa[12] | ṅāḥ[12] |

| 'bitter' | Khổ*kʰaʔ[31] | kha[12] | khāḥ[12] |

| 'kill' | Sát*srjat[32] | -sad[33] | sat[33] |

| 'poison' | Độc*duk[34] | dug[19] | tok<*tuk[19] |

Although the relationship was first proposed in the early 19th century and is now broadly accepted, reconstruction of Sino-Tibetan is much less developed than that of families such asIndo-EuropeanorAustronesian.[35] Although Old Chinese is by far the earliest attested member of the family, its logographic script does not clearly indicate the pronunciation of words.[36] Other difficulties have included the great diversity of the languages, the lack of inflection in many of them, and the effects of language contact. In addition, many of the smaller languages are poorly described because they are spoken in mountainous areas that are difficult to reach, including several sensitive border zones.[37][38]

Initial consonants generally correspond regardingplaceandmanner of articulation,butvoicingandaspirationare much less regular, and prefixal elements vary widely between languages. Some researchers believe that both these phenomena reflect lostminor syllables.[39][40]Proto-Tibeto-Burmanas reconstructed byBenedictandMatisofflacks an aspiration distinction on initial stops and affricates. Aspiration in Old Chinese often corresponds to pre-initial consonants in Tibetan andLolo-Burmese,and is believed to be a Chinese innovation arising from earlier prefixes.[41]Proto-Sino-Tibetan is reconstructed with a six-vowel system as in recent reconstructions of Old Chinese, with theTibeto-Burman languagesdistinguished by themergerof the mid-central vowel*-ə-with*-a-.[42][43]The other vowels are preserved by both, with some alternation between*-e-and*-i-,and between*-o-and*-u-.[44]

History[edit]

| c. 1250 BC |

|

|---|---|

| c. 1046 BC | |

| 771 BC |

|

| 476 BC | |

| 221 BC | Qin unification |

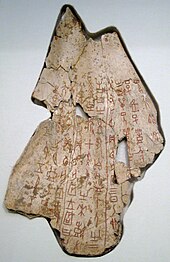

The earliest known written records of the Chinese language were found at theYinxusite near modernAnyangidentified as the last capital of theShang dynasty,and date from about 1250 BC.[45]These are theoracle bones,short inscriptions carved on tortoiseplastronsand oxscapulaefor divinatory purposes, as well as a few briefbronze inscriptions.The language written is undoubtedly an early form of Chinese, but is difficult to interpret due to the limited subject matter and high proportion of proper names. Only half of the 4,000 characters used have been identified with certainty. Little is known about the grammar of this language, but it seems much less reliant ongrammatical particlesthan Classical Chinese.[46]

From early in theWestern Zhouperiod, around 1000 BC, the most important recovered texts are bronze inscriptions, many of considerable length. Even longer pre-Classical texts on a wide range of subjects have also been transmitted through the literary tradition. The oldest sections of theBook of Documents,theClassic of Poetryand theI Ching,also date from the early Zhou period, and closely resemble the bronze inscriptions in vocabulary, syntax, and style. A greater proportion of this more varied vocabulary has been identified than for the oracular period.[47]

The four centuries preceding the unification of China in 221 BC (the laterSpring and Autumn periodand theWarring States period) constitute the Chinese classical period in the strict sense, although some authors also include the subsequentQinandHan dynasties,thus encompassing the next four centuries of the early imperial period.[48]There are many bronze inscriptions from this period, but they are vastly outweighed by a rich literature written in ink onbamboo and wooden slipsand (toward the end of the period) silk and paper. Although these are perishable materials, and many books were destroyed in theburning of books and burying of scholarsin theQin dynasty,a significant number of texts were transmitted as copies, and a few of these survived to the present day as the received classics. Works from this period, including theAnalects,theMencius,theTao Te Ching,theCommentary of Zuo,theGuoyu,and the early HanRecords of the Grand Historian,have been admired as models of prose style by later generations.

During the Han dynasty, disyllabic words proliferated in the spoken language and gradually replaced the mainly monosyllabic vocabulary of the pre-Qin period, while grammatically,noun classifiersbecame a prominent feature of the language.[48][49]While some of these innovations were reflected in the writings of Han dynasty authors (e.g.,Sima Qian),[50]later writers increasingly imitated earlier, pre-Qin literary models. As a result, the syntax and vocabulary of pre-QinClassical Chinesewas preserved in the form ofLiterary Chinese(wenyan), a written standard which served as alingua francafor formal writing in China and neighboringSinospherecountries until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[51]

Script[edit]

Each character of the script represented a single Old Chinese word. Most scholars believe that these words were monosyllabic, though some have recently suggested that a minority of them hadminor presyllables.[52][53]The development of these characters follows the same three stages that characterizedEgyptian hieroglyphs,Mesopotamiancuneiform scriptand theMaya script.[54][55]

Some words could be represented by pictures (later stylized) such asNgàyrì'sun',Ngườirén'person' andMộcmù'tree, wood', by abstract symbols such asTamsān'three' andThượngshàng'up', or by composite symbols such asLâmlín'forest' (two trees). About 1,000 of the oracle bone characters, nearly a quarter of the total, are of this type, though 300 of them have not yet been deciphered. Though the pictographic origins of these characters are apparent, they have already undergone extensive simplification and conventionalization. Evolved forms of most of these characters are still in common use today.[56][57]

Next, words that could not be represented pictorially, such as abstract terms and grammatical particles, were signified by borrowing characters of pictorial origin representing similar-sounding words (the "rebusstrategy "):[58][59]

- The wordlì'tremble' was originally written with the characterLậtforlì'chestnut'.[60]

- The pronoun and modal particleqíwas written with the characterNàyoriginally representingjī'winnowing basket'.[61]

Sometimes the borrowed character would be modified slightly to distinguish it from the original, as withVôwú'don't', a borrowing ofMẫumǔ'mother'.[56] Later, phonetic loans were systematically disambiguated by the addition of semantic indicators, usually to the less common word:

- The wordlì'tremble' was later written with the characterLật,formed by adding the symbolTâm,a variant ofTâmxīn'heart'.[60]

- The less common original wordjī'winnowing basket' came to be written with the compoundKi,obtained by adding the symbolTrúczhú'bamboo' to the character.[61]

Such phono-semantic compound characters were already used extensively on the oracle bones, and the vast majority of characters created since then have been of this type.[62] In theShuowen Jiezi,a dictionary compiled in the 2nd century, 82% of the 9,353 characters are classified as phono-semantic compounds.[63] In the light of the modern understanding of Old Chinese phonology, researchers now believe that most of the characters originally classified as semantic compounds also have a phonetic nature.[64][65]

These developments were already present in the oracle bone script,[66]possibly implying a significant period of development prior to the extant inscriptions.[52] This may have involved writing on perishable materials, as suggested by the appearance on oracle bones of the characterSáchcè'records'. The character is thought to depict bamboo or wooden strips tied together with leather thongs, a writing material known from later archaeological finds.[67]

Development and simplification of the script continued during the pre-Classical and Classical periods, with characters becoming less pictorial and more linear and regular, with rounded strokes being replaced by sharp angles.[68] The language developed compound words, so that characters came to representmorphemes,though almost all morphemes could be used as independent words. Hundreds of morphemes of two or more syllables also entered the language, and were written with one phono-semantic compound character per syllable.[69] During theWarring States period,writing became more widespread, with further simplification and variation, particularly in the eastern states. The most conservative script prevailed in the western state ofQin,which would later impose its standard on the whole of China.[70]

Phonology[edit]

Old Chinese phonology has been reconstructed using a variety of evidence, including the phonetic components of Chinese characters, rhyming practice in theClassic of PoetryandMiddle Chinesereading pronunciations described in such works as theQieyun,arhyme dictionarypublished in 601 AD. Although many details are still disputed, recent formulations are in substantial agreement on the core issues.[71] For example, the Old Chinese initial consonants recognized byLi Fang-KueiandWilliam Baxterare given below, with Baxter's (mostly tentative) additions given in parentheses:[72][73][74]

| Labial | Dental | Palatal [d] |

Velar | Laryngeal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | plain | labialized | plain | labialized | ||||

| Stopor affricate |

voiceless | *p | *t | *ts | *k | *kʷ | *ʔ | *ʔʷ | |

| aspirate | *pʰ | *tʰ | *tsʰ | *kʰ | *kʷʰ | ||||

| voiced | *b | *d | *dz | *ɡ | *ɡʷ | ||||

| Nasal | voiceless | *m̥ | *n̥ | *ŋ̊ | *ŋ̊ʷ | ||||

| voiced | *m | *n | *ŋ | *ŋʷ | |||||

| Lateral | voiceless | *l̥ | |||||||

| voiced | *l | ||||||||

| Fricativeor approximant |

voiceless | (*r̥) | *s | (*j̊) | *h | *hʷ | |||

| voiced | *r | (*z) | (*j) | (*ɦ) | (*w) | ||||

Various initial clusters have been proposed, especially clusters of*s-with other consonants, but this area remains unsettled.[76]

Bernhard Karlgrenand many later scholars posited the medials*-r-,*-j-and the combination*-rj-to explain the retroflex and palatalobstruentsof Middle Chinese, as well as many of its vowel contrasts.[77] *-r-is generally accepted. However, although the distinction denoted by*-j-is universally accepted, its realization as a palatal glide has been challenged on a number of grounds, and a variety of different realizations have been used in recent constructions.[78][79]

Reconstructions since the 1980s usually propose sixvowels:[80][e][f]

| *i | *ə | *u |

| *e | *a | *o |

Vowels could optionally be followed by the same codas as in Middle Chinese: a glide*-jor*-w,a nasal*-m,*-nor*-ŋ,or a stop*-p,*-tor*-k.Some scholars also allow for a labiovelar coda*-kʷ.[84] Most scholars now believe that Old Chinese lacked thetonesfound in later stages of the language, but had optional post-codas*-ʔand*-s,which developed into the Middle Chinese rising and departing tones respectively.[85]

Grammar[edit]

Little is known of the grammar of the language of the Oracular and pre-Classical periods, as the texts are often of a ritual or formulaic nature, and much of their vocabulary has not been deciphered. In contrast, the rich literature of theWarring States periodhas been extensively analysed.[86]Having noinflection,Old Chinese was heavily reliant on word order,grammatical particles,and inherentword classes.[86][87]

Word classes[edit]

Classifying Old Chinese words is not always straightforward, as words were not marked for function, word classes overlapped, and words of one class could sometimes be used in roles normally reserved for a different class.[88]The task is more difficult with written texts than it would have been for speakers of Old Chinese, because the derivational morphology is often hidden by the writing system.[89][90]For example, the verb*sək'to block' and the derived noun*səks'frontier' were both written with the same characterTắc.[91]

Personal pronounsexhibit a wide variety of forms in Old Chinese texts, possibly due to dialectal variation.[92] There were two groups of first-person pronouns:[92][93]

In the oracle bone inscriptions, the*l-pronouns were used by the king to refer to himself, and the*ŋ-forms for the Shang people as a whole. This distinction is largely absent in later texts, and the*l-forms disappeared during the classical period.[93] In the post-Han period,Tacame to be used as the general first-person pronoun.[95]

Second-person pronouns included*njaʔNhữ,*njəjʔNgươi,*njəMà,*njakNếu.[96] The formsNhữandNgươicontinued to be used interchangeably until their replacement by the northwestern variantNgươi(modern Mandarinnǐ) in theTangperiod.[95] However, in someMindialects the second-person pronoun is derived fromNhữ.[97]

Case distinctions were particularly marked among third-person pronouns.[98] There was no third-person subject pronoun, but*tjəChi,originally a distaldemonstrative,came to be used as a third-person object pronoun in the classical period.[98][99] The possessive pronoun was originally*kjotXỉu,replaced in the classical period by*ɡjəNày.[100] In the post-Han period,Nàycame to be used as the general third-person pronoun.[95] It survives in someWudialects, but has been replaced by a variety of forms elsewhere.[95]

There were demonstrative andinterrogative pronouns,but noindefinite pronounswith the meanings 'something' or 'nothing'.[101] Thedistributive pronounswere formed with a*-ksuffix:[102][103]

- *djukAi'which one' from*djujAi'who'

- *kakCác'each one' from*kjaʔCử'all'

- *wəkHoặc'someone' from*wjəʔCó'there is'

- *makMạc'no-one' from*mjaVô'there is no'

As in the modern language, localizers (compass directions, 'above', 'inside' and the like) could be placed after nouns to indicate relative positions. They could also precede verbs to indicate the direction of the action.[102]Nouns denoting times were another special class (time words); they usually preceded the subject to specify the time of an action.[104]However theclassifiersso characteristic of Modern Chinese only became common in theHan periodand the subsequentNorthern and Southern dynasties.[105]

Old Chineseverbs,like their modern counterparts, did not show tense or aspect; these could be indicated with adverbs or particles if required. Verbs could betransitiveorintransitive.As in the modern language,adjectiveswere a special kind of intransitive verb, and a few transitive verbs could also function asmodal auxiliariesor asprepositions.[106]

Adverbsdescribed the scope of a statement or various temporal relationships.[107]They included two families of negatives starting with*p-and*m-,such as*pjəKhôngand*mjaVô.[108]Modern northern varieties derive the usual negative from the first family, while southern varieties preserve the second.[109]The language had no adverbs of degree until late in the Classical period.[110]

Particleswerefunction wordsserving a range of purposes. As in the modern language, there were sentence-final particles markingimperativesandyes/no questions.Other sentence-final particles expressed a range of connotations, the most important being*ljajCũng,expressing static factuality, and*ɦjəʔRồi,implying a change. Other particles included the subordination marker*tjəChiand the nominalizing particles*tjaʔGiả(agent) and*srjaʔSở(object).[111] Conjunctionscould join nouns or clauses.[112]

Sentence structure[edit]

As with English and modern Chinese, Old Chinese sentences can be analysed as asubject(a noun phrase, sometimes understood) followed by apredicate,which could be of either nominal or verbal type.[113][114]

Before the Classical period, nominal predicates consisted of acopularparticle*wjijDuyfollowed by a noun phrase:[115][116]

The negated copula*pjə-wjijKhôngDuyis attested in oracle bone inscriptions, and later fused as*pjəjPhi. In the Classical period, nominal predicates were constructed with the sentence-final particle*ljajCũnginstead of the copulaDuy,butPhiwas retained as the negative form, with whichCũngwas optional:[117][118]

Này

*ɡjə

its

Đến

*tjits

arrive

Ngươi

*njəjʔ

you

Lực

*C-rjək

strength

Cũng

*ljajʔ

FP

Này

*ɡjə

its

Trung

*k-ljuŋ

centre

Phi

*pjəj

not

Ngươi

*njəjʔ

you

Lực

*C-rjək

strength

Cũng

*ljajʔ

FP

(of shooting at a mark a hundred paces distant) 'That you reach it is owing to your strength, but that you hit the mark is not owing to your strength.' (Mencius10.1/51/13)[89]

The copular verbLà(shì) of Literary and Modern Chinese dates from the Han period. In Old Chinese the word was a neardemonstrative('this').[119]

As in Modern Chinese, but unlike most Tibeto-Burman languages, the basic word order in a verbal sentence wassubject–verb–object:[120][121]

Mạnh Tử

*mraŋs-*tsjəʔ

Mencius

Thấy

*kens

see

Lương

*C-rjaŋ

Liang

Huệ

*wets

Hui

Vương

*wjaŋ

king

'Mencius saw King Hui of Liang.' (Mencius1.1/1/3)[122]

Besides inversions for emphasis, there were two exceptions to this rule: a pronoun object of a negated sentence or an interrogative pronoun object would be placed before the verb:[120]

Tuổi

*swjats

year

Không

*pjə

not

Ta

*ŋajʔ

me

Cùng

*ljaʔ

wait

'The years do not wait for us.' (Analects17.1/47/23)

An additional noun phrase could be placed before the subject to serve as thetopic.[123]As in the modern language,yes/no questionswere formed by adding a sentence-final particle, and requests for information by substituting aninterrogative pronounfor the requested element.[124]

Modification[edit]

In general, Old Chinese modifiers preceded the words they modified. Thusrelative clauseswere placed before the noun, usually marked by the particle*tjəChi(in a role similar to Modern Chinesede):[125][126]

Không

*pjə

not

Nhẫn

*njənʔ

endure

Người

*njin

person

Chi

*tjə

REL

Tâm

*sjəm

heart

'... the heart that cannot bear the afflictions of others.' (Mencius3.6/18/4)[125]

A common instance of this construction was adjectival modification, since the Old Chinese adjective was a type of verb (as in the modern language), butChiwas usually omitted after monosyllabic adjectives.[125]

Similarly, adverbial modifiers, including various forms of negation, usually occurred before the verb.[127]As in the modern language, timeadjunctsoccurred either at the start of the sentence or before the verb, depending on their scope, while duration adjuncts were placed after the verb.[128]Instrumental and place adjuncts were usually placed after the verb phrase. These later moved to a position before the verb, as in the modern language.[129]

Vocabulary[edit]

The improved understanding of Old Chinesephonologyhas enabled the study of the origins of Chinese words (rather than the characters with which they are written). Most researchers trace the core vocabulary to aSino-Tibetanancestor language, with much early borrowing from other neighbouring languages.[130] The traditional view was that Old Chinese was anisolating language,lacking bothinflectionandderivation,but it has become clear that words could be formed by derivational affixation, reduplication and compounding.[131] Most authors consider only monosyllabicroots,but Baxter andLaurent Sagartalso propose disyllabic roots in which the first syllable is reduced, as in modernKhmer.[53]

Loanwords[edit]

During the Old Chinese period, Chinese civilization expanded from a compact area around the lowerWei Riverand middleYellow Rivereastwards across theNorth China PlaintoShandongand then south into the valley of theYangtze.There are no records of the non-Chinese languages formerly spoken in those areas and subsequently displaced by the Chinese expansion. However they are believed to have contributed to the vocabulary of Old Chinese, and may be the source of some of the many Chinese words whose origins are still unknown.[132][133]

Jerry NormanandMei Tsu-linhave identified earlyAustroasiaticloanwords in Old Chinese, possibly from the peoples of the lowerYangtzebasin known to ancient Chinese as theYue.For example, the early Chinese name*kroŋ(Giangjiāng) for the Yangtze was later extended to a general word for 'river' in south China. Norman and Mei suggest that the word is cognate withVietnamesesông(from *krong) andMonkruŋ'river'.[134][135][136]

Haudricourt and Strecker have proposed a number of borrowings from theHmong–Mien languages.These include terms related toricecultivation, which began in the middle Yangtze valley:

- *ʔjaŋ(Ươngyāng) 'rice seedling' fromproto-Hmong–Mien*jaŋ

- *luʔ(Lúadào) 'unhulled rice' from proto-Hmong–Mien*mblauA[137]

Other words are believed to have been borrowed from languages to the south of the Chinese area, but it is not clear which was the original source, e.g.

- *zjaŋʔ(Tượngxiàng) 'elephant' can be compared with Moncoiŋ,proto-Tai*jaŋCand Burmesechaŋ.[138]

- *ke(Gàjī) 'chicken' versus proto-Tai*kəiB,proto-Hmong–Mien*kaiandproto-Viet–Muong*r-ka.[139]

In ancient times, theTarim Basinwas occupied by speakers ofIndo-EuropeanTocharian languages,the source of*mjit(Mậtmì) 'honey', from proto-Tocharian *ḿət(ə)(where *ḿispalatalized;cf. Tocharian Bmit), cognate with Englishmead.[140][h] The northern neighbours of Chinese contributed such words as*dok(Nghédú) 'calf' – compareMongoliantuɣulandManchutuqšan.[143]

Affixation[edit]

Chinese philologists have long noted words with related meanings and similar pronunciations, sometimes written using the same character.[144][145] Henri Masperoattributed some of these alternations to consonant clusters resulting from derivational affixes.[146] Subsequent work has identified several such affixes, some of which appear to have cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages.[147][148]

A common case is "derivation by tone change", in which words in the departing tone appear to be derived from words in other tones.[149] If Haudricourt's theory of the origin of the departing tone is accepted, these tonal derivations can be interpreted as the result of a derivational suffix*-s. As Tibetan has a similar suffix, it may be inherited from Sino-Tibetan.[150] Examples include:

- *dzjin(Tẫnjìn) 'to exhaust' and*dzjins(Tẫnjìn) 'exhausted, consumed, ash'[151]

- *kit(Kếtjié) 'to tie' and*kits(Búi tócjì) 'hair-knot'[152]

- *nup(Nạpnà) 'to bring in' and*nuts<*nups(Nộinèi) 'inside'[153]

- *tjək(Dệtzhī) 'to weave' and*tjəks(Dệtzhì) 'silk cloth' (compare Written Tibetanʼthag'to weave' andthags'woven, cloth')[154]

Another alternation involves transitive verbs with an unvoiced initial and passive or stative verbs with a voiced initial:[155]

- *kens(Thấyjiàn) 'to see' and*ɡens(Hiệnxiàn) 'to appear'[156]

- *kraw(Giaojiāo) 'to mix' and*ɡraw(Hàoyáo) 'mixed, confused'[157]

- *trjaŋ(Trươngzhāng) 'to stretch' and*drjaŋ(Trườngcháng) 'long'[158]

Some scholars hold that the transitive verbs with voiceless initials are basic and the voiced initials reflect a de-transitivizing nasal prefix.[159] Others suggest that the transitive verbs were derived by the addition of a causative prefix*s-to a stative verb, causing devoicing of the following voiced initial.[160] Both postulated prefixes have parallels in other Sino-Tibetan languages, in some of which they are still productive.[161][162] Several other affixes have been proposed.[163][164]

Reduplication and compounding[edit]

Old Chinese morphemes were originally monosyllabic, but during the Western Zhou period many new disyllabic words entered the language. By the classical period, 25–30% of the lexicon was polysyllabic, though monosyllabic words occurred more frequently and made up 80–90% of the text.[165]Many disyllabic, monomorphemic words, particularly names of insects, birds and plants, and expressive adjectives and adverbs, were formed by varieties ofreduplication(liánmián cíLiên miên từ/Liên miên từ):[166][167][i]

- full reduplication (diézìTừ láy'repeated words'), in which the syllable is repeated, as in*ʔjuj-ʔjuj(Uy uywēiwēi) 'tall and grand' and*ljo-ljo(Du duyúyú) 'happy and at ease'.[166]

- rhyming semi-reduplication (diéyùnĐiệp vần'repeated rhymes'), in which only the final is repeated, as in*ʔiwʔ-liwʔ(Yểu điệuyǎotiǎo) 'elegant, beautiful' and*tsʰaŋ-kraŋ(Chim thương canh[j]cānggēng) 'oriole'.[169][170]The initial of the second syllable is often*l-or*r-.[171]

- alliterative semi-reduplication (shuāngshēngSong thanh'paired initials'), in which the initial is repeated, as in*tsʰrjum-tsʰrjaj(So lecēncī) 'irregular, uneven' and*ʔaŋ-ʔun(Uyên ươngyuānyāng) 'mandarin duck'.[169]

- vowel alternation, especially of*-e-and*-o-,as in*tsʰjek-tsʰjok(Thứ xúcqìcù) 'busy' and*ɡreʔ-ɡroʔ(Tình cờ gặp gỡxièhòu) 'carefree and happy'.[172]Alternation between*-i-and*-u-also occurred, as in*pjit-pjut(Tất phíbìfú) 'rushing (of wind or water)' and*srjit-srjut(Con dế mènxīshuài) 'cricket'.[173]

Other disyllabic morphemes include thefamous*ɡa-lep(Hồ điệp[k]húdié) 'butterfly' from theZhuangzi.[175] More words, especially nouns, were formed bycompounding,including:

- qualification of one noun by another (placed in front), as in*mok-kʷra(Đu đủmùguā) 'quince' (literally 'tree-melon'), and*trjuŋ-njit(Trung ngàyzhōngrì) 'noon' (literally 'middle-day').[176]

- verb–object compounds, as in*sjə-mraʔ(Tư Mãsīmǎ) 'master of the household' (literally 'manage-horse'), and*tsak-tsʰrek(Làm sáchzuòcè) 'scribe' (literally 'make-writing').[177]

However the components of compounds were notbound morphemes:they could still be used separately.[178]

A number of bimorphemic syllables appeared in the Classical period, resulting from the fusion of words with following unstressed particles or pronouns. Thus the negatives*pjutPhấtand*mjutChớare viewed as fusions of the negators*pjəKhôngand*mjoVôrespectively with a third-person pronoun*tjəChi.[179]

Notes[edit]

- ^abThe time interval assigned to Old Chinese varies between authors. Some scholars limit it to the earlyZhou,based on the availability of documentary evidence of the phonology. Many include the whole Zhou period and often the earliest written evidence from the lateShang,while some also include the Qin, Han and occasionally even later periods.[1] The ancestor of the oldest layer of theMinlanguages is believed to have split off from the other varieties of Chinese during the Han dynasty.[2]

- ^Reconstructed Old Chinese forms are starred, and followBaxter (1992)with some graphical substitutions from his more recent work: *əfor*ɨ[10]and consonants rendered according to IPA conventions.

- ^The notation "*C-" indicates that there is evidence of an Old Chinese consonant before *r, but the particular consonant cannot be identified.[21]

- ^Baxter describes his reconstruction of the palatal initials as "especially tentative, being based largely on scanty graphic evidence".[75]

- ^The vowel here written as*əis treated as*ɨ,*əor*ɯby different authors.

- ^The six-vowel system represents a re-analysis of a system proposed by Li and still used by some authors, comprising four vowels*i,*u,*əand*aand three diphthongs.[81]Li's diphthongs*iaand*uacorrespond to*eand*orespectively, while Li's*iəbecomes*ior*əin different contexts.[82][83]

- ^In the later reading tradition, dư (when used as a pronoun) is treated as a graphical variant of dư. In theShijing,however, both pronoun and verb usages of dư rhyme in the rising tone.[93][94]

- ^Jacquesproposed a different, unattested, Tocharian form as the source.[141]Meier and Peyrot recently defended the traditional Tocharian etymology.[142]

- ^All examples are found in theShijing.

- ^This word was later written asThương canh.[168]

- ^During the Old Chinese period, the word for butterfly was written as hồ điệp.[174]During later centuries, the 'insect' radical ( trùng ) was added to the first character to give the modern con bướm.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^Tai & Chan (1999),pp. 225–233.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (2014),p. 33.

- ^Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Morphology in Old Chinese".Journal of Chinese Linguistics.28(1): 26–51.JSTOR23754003.

- ^Wang, Li, 1900–1986.; vương lực, 1900–1986 (1980).Han yu shi gao(2010 reprint ed.). Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju. pp. 302–311.ISBN7101015530.OCLC17030714.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Norman (1988),pp. 8–12.

- ^Enfield (2005),pp. 186–193.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 12–13.

- ^Coblin (1986),pp. 35–164.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 13.

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 122.

- ^GSR58f;Baxter (1992),p. 208.

- ^abcdefghijHill (2012),p. 46.

- ^GSR94j;Baxter (1992),p. 453.

- ^Hill (2012),p. 48.

- ^GSR103a;Baxter (1992),p. 47.

- ^GSR564a;Baxter (1992),p. 317.

- ^abHill (2012),p. 8.

- ^GSR648a;Baxter (1992),p. 785.

- ^abcdefHill (2012),p. 27.

- ^GSR58a;Baxter (1992),p. 795.

- ^Baxter (1992),p. 201.

- ^GSR1032a;Baxter (1992),p. 774.

- ^GSR404a;Baxter (1992),p. 785.

- ^abcdHill (2012),p. 9.

- ^GSR826a;Baxter (1992),p. 777.

- ^abHill (2012),p. 12.

- ^GSR981a;Baxter (1992),p. 756.

- ^abHill (2012),p. 15.

- ^GSR399e;Baxter (1992),p. 768.

- ^GSR79a;Baxter (1992),p. 209.

- ^GSR49u;Baxter (1992),p. 771.

- ^GSR319d;Baxter (1992),p. 407.

- ^abHill (2012),p. 51.

- ^GSR1016a;Baxter (1992),p. 520.

- ^Handel (2008),p. 422.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 14.

- ^Handel (2008),pp. 434–436.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 15–16.

- ^Coblin (1986),p. 11.

- ^Handel (2008),pp. 425–426.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. 58–63.

- ^Gong (1980),pp. 476–479.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. 2, 105.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. 110–117.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (2014),p. 1.

- ^Boltz (1999),pp. 88–89.

- ^Boltz (1999),p. 89.

- ^abNorman, Jerry.Chinese.Cambridge. pp. 112–117.ISBN0521228093.OCLC15629375.

- ^Wang, Li, 1900–1986.; vương lực, 1900–1986 (1980).Han yu shi gao(2010 Reprint ed.). Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju. pp. 275–282.ISBN7-101-01553-0.OCLC17030714.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Pulleyblank (1996),pp. 4.

- ^Boltz (1999),p. 90.

- ^abNorman (1988),p. 58.

- ^abBaxter & Sagart (2014),pp. 50–53.

- ^Boltz (1994),pp. 52–72.

- ^Boltz (1999),p. 109.

- ^abWilkinson (2012),p. 36.

- ^Boltz (1994),pp. 52–57.

- ^Boltz (1994),pp. 59–62.

- ^Boltz (1999),pp. 114–118.

- ^abGSR403;Boltz (1999),p. 119.

- ^abGSR952;Norman (1988),p. 60.

- ^Boltz (1994),pp. 67–72.

- ^Wilkinson (2012),pp. 36–37.

- ^Boltz (1994),pp. 147–149.

- ^Schuessler (2009),pp. 31–32, 35.

- ^Boltz (1999),p. 110.

- ^Boltz (1999),p. 107.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 61–62.

- ^Boltz (1994),pp. 171–172.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 62–63.

- ^Schuessler (2009),p. x.

- ^Li (1974–1975),p. 237.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 46.

- ^Baxter (1992),pp. 188–215.

- ^Baxter (1992),p. 203.

- ^Baxter (1992),pp. 222–232.

- ^Baxter (1992),pp. 235–236.

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 95.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (2014),pp. 68–71.

- ^Baxter (1992),p. 180.

- ^Li (1974–1975),p. 247.

- ^Baxter (1992),pp. 253–256.

- ^Handel (2003),pp. 556–557.

- ^Baxter (1992),p. 291.

- ^Baxter (1992),pp. 181–183.

- ^abHerforth (2003),p. 59.

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 12.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 87–88.

- ^abHerforth (2003),p. 60.

- ^Aldridge (2013),pp. 41–42.

- ^Baxter (1992),p. 136.

- ^abNorman (1988),p. 89.

- ^abcPulleyblank (1996),p. 76.

- ^Baxter (1992),p. 805.

- ^abcdNorman (1988),p. 118.

- ^Pulleyblank (1996),p. 77.

- ^Sagart (1999),p. 143.

- ^abAldridge (2013),p. 43.

- ^Pulleyblank (1996),p. 79.

- ^Pulleyblank (1996),p. 80.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 90–91.

- ^abNorman (1988),p. 91.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. 70, 457.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 91, 94.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 115–116.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 91–94.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 94.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 97–98.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. 172–173, 518–519.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 94, 127.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 94, 98–100, 105–106.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 94, 106–108.

- ^Pulleyblank (1996),pp. 13–14.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 95.

- ^Pulleyblank (1996),p. 22.

- ^abSchuessler (2007),p. 14.

- ^Pulleyblank (1996),pp. 16–18, 22.

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 232.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 125–126.

- ^abPulleyblank (1996),p. 14.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 10–11, 96.

- ^Pulleyblank (1996),p. 13.

- ^Herforth (2003),pp. 66–67.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 90–91, 98–99.

- ^abcPulleyblank (1996),p. 62.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 104–105.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 105.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 103–104.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 103, 130–131.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. xi, 1–5, 7–8.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (1998),pp. 35–36.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 4, 16–17.

- ^Boltz (1999),pp. 75–76.

- ^Norman & Mei (1976),pp. 280–283.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 17–18.

- ^Baxter (1992),p. 573.

- ^Haudricourt & Strecker (1991);Baxter (1992),p. 753;GSR1078h;Schuessler (2007),pp. 207–208, 556.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 19;GSR728a; OC fromBaxter (1992),p. 206.

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 292;GSR876n; OC fromBaxter (1992),p. 578.

- ^Boltz (1999),p. 87;Schuessler (2007),p. 383;Baxter (1992),p. 191;GSR405r; Proto-Tocharian and Tocharian B forms fromPeyrot (2008),p. 56.

- ^Jacques (2014).

- ^Meier & Peyrot (2017).

- ^Norman (1988),p. 18;GSR1023l.

- ^Handel (2015),p. 76.

- ^Sagart (1999),p. 1.

- ^Maspero (1930),pp. 323–324.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (2014),pp. 53–60.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. 14–22.

- ^Downer (1959),pp. 258–259.

- ^Baxter (1992),pp. 315–317.

- ^GSR381a,c;Baxter (1992),p. 768;Schuessler (2007),p. 45.

- ^GSR393p,t;Baxter (1992),p. 315.

- ^GSR695h,e;Baxter (1992),p. 315;Schuessler (2007),p. 45.

- ^GSR920f;Baxter (1992),p. 178;Schuessler (2007),p. 16.

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 49.

- ^GSR241a,e;Baxter (1992),p. 218.

- ^GSR1166a, 1167e;Baxter (1992),p. 801.

- ^GSR721h,a;Baxter (1992),p. 324.

- ^Handel (2012),pp. 63–64, 68–69.

- ^Handel (2012),pp. 63–64, 70–71.

- ^Handel (2012),pp. 65–68.

- ^Sun (2014),pp. 638–640.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (1998),pp. 45–64.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. 38–50.

- ^Wilkinson (2012),pp. 22–23.

- ^abNorman (1988),p. 87.

- ^Li (2013),p. 1.

- ^Qiu (2000),p. 338.

- ^abBaxter & Sagart (1998),p. 65.

- ^Li (2013),p. 144.

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 24.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (1998),pp. 65–66.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (1998),p. 66.

- ^GSR49a'.

- ^GSR633h;Baxter (1992),p. 411.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (1998),p. 67.

- ^Baxter & Sagart (1998),p. 68.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 86.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 85, 98.

Works cited[edit]

- Aldridge, Edith (2013), "Survey of Chinese historical syntax part I: pre-Archaic and Archaic Chinese",Language and Linguistics Compass,7(1): 39–57,doi:10.1111/lnc3.12006.

- Baxter, William H.(1992),A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology,Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter,ISBN978-3-11-012324-1.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (1998), "Word formation in Old Chinese", in Packard, Jerome Lee (ed.),New approaches to Chinese word formation: morphology, phonology and the lexicon in modern and ancient Chinese,Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 35–76,ISBN978-3-11-015109-1.

- ———; ——— (2014),Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction,Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0-19-994537-5.

- Boltz, William (1994),The origin and early development of the Chinese writing system,American Oriental Society,ISBN978-0-940490-78-9.

- ——— (1999), "Language and Writing", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.),The Cambridge History of Ancient China,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 74–123,doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.004,ISBN978-0-521-47030-8.

- Coblin, W. South(1986),A Sinologist's Handlist of Sino-Tibetan Lexical Comparisons,Monumenta Sericamonograph series, vol. 18, Steyler Verlag,ISBN978-3-87787-208-6.

- Downer, G. B. (1959), "Derivation by tone-change in Classical Chinese",Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies,22(1/3): 258–290,doi:10.1017/s0041977x00068701,JSTOR609429,S2CID122377268.

- Enfield, N. J. (2005), "Areal Linguistics and Mainland Southeast Asia",Annual Review of Anthropology,34:181–206,doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120406,hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-167B-C.

- Gong, Hwang-cherng(1980), "A Comparative Study of the Chinese, Tibetan, and Burmese Vowel Systems",Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology,51(3), Academia Sinica: 455–489.

- Handel, Zev J. (2003),"Appendix A: A Concise Introduction to Old Chinese Phonology",Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman: System and Philosophy of Sino-Tibetan Reconstruction,byMatisoff, James,Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 543–576,ISBN978-0-520-09843-5.

- ——— (2008), "What is Sino-Tibetan? Snapshot of a field and a language family in flux",Language and Linguistics Compass,2(3): 422–441,doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00061.x.

- ——— (2012),"Valence-changing prefixes and voicing alternation in Old Chinese and Proto-Sino-Tibetan: reconstructing *s- and *N- prefixes"(PDF),Language and Linguistics,13(1): 61–82.

- ——— (2015), "Old Chinese Phonology", in S-Y. Wang, William; Sun, Chaofen (eds.),The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics,Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 68–79,ISBN978-0-19-985633-6.

- Haudricourt, André G.;Strecker, David (1991), "Hmong–Mien (Miao–Yao) loans in Chinese",T'oung Pao,77(4–5): 335–342,doi:10.1163/156853291X00073,JSTOR4528539.

- Herforth, Derek (2003), "A sketch of Late Zhou Chinese grammar", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.),The Sino-Tibetan languages,London: Routledge, pp. 59–71,ISBN978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Hill, Nathan W.(2012),"The six vowel hypothesis of Old Chinese in comparative context",Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics,6(2): 1–69,doi:10.1163/2405478X-90000100.

- Jacques, Guillaume(2014),"The word for 'honey' in Chinese and its relevance for the study of Indo-European and Sino-Tibetan language contact",*Wékwos,1:111–116.

- Karlgren, Bernhard(1957),Grammata Serica Recensa,Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities,OCLC1999753.

- Li, Fang-Kuei(1974–1975), "Studies on Archaic Chinese",Monumenta Serica,31,translated by Mattos, Gilbert L.: 219–287,doi:10.1080/02549948.1974.11731100,JSTOR40726172.

- Li, Jian (2013),The Rise of Disyllables in Old Chinese: The Role of Lianmian Words(PhD thesis), City University of New York.

- Maspero, Henri(1930),"Préfixes et dérivation en chinois archaïque",Mémoires de la Société de Linguistique de Paris(in French),23(5): 313–327.

- Meier, Kristin; Peyrot, Michaël (2017), "The Word for 'Honey' in Chinese, Tocharian and Sino-Vietnamese",Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft,167(1): 7–22,doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.167.1.0007.

- Norman, Jerry;Mei, Tsu-lin (1976),"The Austroasiatics in Ancient South China: Some Lexical Evidence"(PDF),Monumenta Serica,32:274–301,doi:10.1080/02549948.1976.11731121,JSTOR40726203.

- Norman, Jerry(1988),Chinese,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0-521-29653-3.

- Peyrot, Michaël (2008),Variation and Change in Tocharian B,Amsterdam: Rodopoi,ISBN978-90-420-2401-4.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G.(1996),Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar,University of British Columbia Press,ISBN978-0-7748-0541-4.

- Qiu, Xigui(2000),Chinese writing,translated by Mattos, Gilbert L.; Norman, Jerry, Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China and The Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California,ISBN978-1-55729-071-7.(English translation ofWénzìxué GàiyàoVăn tự học điểm chính,Shangwu, 1988.)

- Sagart, Laurent(1999),The Roots of Old Chinese,Amsterdam: John Benjamins,ISBN978-90-272-3690-6.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007),ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese,Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press,ISBN978-0-8248-2975-9.

- ——— (2009),Minimal Old Chinese and Later Han Chinese: A Companion to Grammata Serica Recensa,Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press,ISBN978-0-8248-3264-3.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L.(1999), "Western Zhou History", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.),The Cambridge History of Ancient China,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 292–351,doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.007,ISBN978-0-521-47030-8.

- Sun, Jackson T.-S. (2014), "Sino-Tibetan: Rgyalrong", in Lieber, Rochelle; Štekauer, Pavol (eds.),The Oxford Handbook of Derivational Morphology,Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 630–650,ISBN978-0-19-165177-9.

- Tai, James H-Y.; Chan, Marjorie K.M. (1999),"Some reflections on the periodization of the Chinese language"(PDF),in Peyraube, Alain; Sun, Chaofen (eds.),In Honor of Mei Tsu-Lin: Studies on Chinese Historical Syntax and Morphology,Paris: Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, pp. 223–239,ISBN978-2-910216-02-3.

- Wilkinson, Endymion(2012),Chinese History: A New Manual,Harvard University Press,ISBN978-0-674-06715-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Dobson, W.A.C.H. (1959),Late Archaic Chinese: A Grammatical Study,Toronto: University of Toronto Press,ISBN978-0-8020-7003-6.

- ——— (1962),Early Archaic Chinese: A Descriptive Grammar,Toronto: University of Toronto Press,OCLC186653632.

- Jacques, Guillaume(2016),"The Genetic Position of Chinese",in Sybesma, Rint; Behr, Wolfgang; Gu, Yueguo; Handel, Zev; Huang, C.-T. James; Myers, James (eds.),Encyclopedia of Chinese Languages and Linguistics,BRILL,ISBN978-90-04-18643-9.

External links[edit]

- Miyake, Marc(2001),"Laurent Sagart:The Roots of Old Chinese",Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale,30(2): 257–268,doi:10.1163/19606028-90000092.(review ofSagart (1999))

- Miyake, Marc (2011)."Why are rhinos late?".Old Chinese articles.

- Miyake, Marc (2012)."A *slo-lution to the p-ro-blem ".Old Chinese articles.

- Miyake, Marc (2013)."Pri-zu-ner ".Old Chinese articles.

- Miyake, Marc (2013)."Did Old Chinese palatal initials always condition higher vowels?".Old Chinese articles.

- Miyake, Marc (2013)."Are Old Chinese disharmonic disyllabic words borrowings?".Old Chinese articles.

- Miyake, Marc (2015)."Did Old Chinese really have so much *(-)r-?".Old Chinese articles.

- Schuessler, Axel (2000),"Book Review:The Roots of Old Chinese"(PDF),Language and Linguistics,1(2): 257–267.(review ofSagart (1999))

- Starostin, Georgiy(2009),"Axel Schuessler:ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese"(PDF),Journal of Language Relationship,1:155–162.(review ofSchuessler (2007))

- Recent Advances in Old Chinese Historical Phonology