Opera

Operais a form oftheatrein whichmusicis a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken bysingers.Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera" ) is typically a collaboration between acomposerand alibrettist[1]and incorporates a number of theperforming arts,such asacting,scenery,costume,and sometimesdanceorballet.The performance is typically given in anopera house,accompanied by anorchestraor smallermusical ensemble,which since the early 19th century has been led by aconductor.Althoughmusical theatreis closely related to opera, the two are considered to be distinct from one another.[2]

Opera is a key part ofWesternclassical music,and Italian tradition in particular.[3]Originally understood as an entirely sung piece, in contrast to a play with songs, opera has come to includenumerous genres,including some that include spoken dialogue such asSingspielandOpéra comique.In traditionalnumber opera,singers employ two styles of singing:recitative,a speech-inflected style,[4]and self-containedarias.The 19th century saw the rise of the continuousmusic drama.

Opera originatedinItalyat the end of the 16th century (withJacopo Peri's mostlylostDafne,produced inFlorencein 1598) especially from works byClaudio Monteverdi,notablyL'Orfeo,and soon spread through the rest of Europe:Heinrich Schützin Germany,Jean-Baptiste Lullyin France, andHenry Purcellin England all helped to establish their national traditions in the 17th century. In the 18th century, Italian opera continued to dominate most of Europe (except France), attracting foreign composers such asGeorge Frideric Handel.Opera seriawas the most prestigious form of Italian opera, untilChristoph Willibald Gluckreacted against its artificiality with his "reform" operas in the 1760s. The most renowned figure of late 18th-century opera isWolfgang Amadeus Mozart,who began with opera seria but is most famous for his Italiancomic operas,especiallyThe Marriage of Figaro(Le nozze di Figaro),Don Giovanni,andCosì fan tutte,as well asDie Entführung aus dem Serail(The Abduction from the Seraglio), andThe Magic Flute(Die Zauberflöte), landmarks in the German tradition.

The first third of the 19th century saw the high point of thebel cantostyle, withGioachino Rossini,Gaetano DonizettiandVincenzo Belliniall creating signature works of that style. It also saw the advent ofgrand operatypified by the works ofDaniel AuberandGiacomo Meyerbeeras well asCarl Maria von Weber's introduction of GermanRomantische Oper(German Romantic Opera). The mid-to-late 19th century was a golden age of opera, led and dominated byGiuseppe Verdiin Italy andRichard Wagnerin Germany. The popularity of opera continued through theverismoera in Italy and contemporaryFrench operathrough toGiacomo PucciniandRichard Straussin the early 20th century. During the 19th century, parallel operatic traditions emerged in central and eastern Europe, particularly inRussiaandBohemia.The 20th century saw many experiments with modern styles, such asatonalityandserialism(Arnold SchoenbergandAlban Berg),neoclassicism(Igor Stravinsky), andminimalism(Philip GlassandJohn Adams). With the rise ofrecording technology,singers such asEnrico CarusoandMaria Callasbecame known to much wider audiences that went beyond the circle of opera fans. Since the invention of radio and television, operas were also performed on (and written for) these media. Beginning in 2006, a number of major opera houses began to present livehigh-definition videotransmissions of their performances incinemasall over the world. Since 2009, complete performances can be downloaded and arelive streamed.

Operatic terminology

[edit]

The words of an opera are known as thelibretto(meaning "small book" ). Some composers, notably Wagner, have written their own libretti; others have worked in close collaboration with their librettists, e.g. Mozart withLorenzo Da Ponte.Traditional opera, often referred to as "number opera",consists of two modes of singing:recitative,the plot-driving passages sung in a style designed to imitate and emphasize the inflections of speech,[4]andaria(an "air" or formal song) in which the characters express their emotions in a more structured melodic style. Vocal duets, trios and other ensembles often occur, and choruses are used to comment on the action. In some forms of opera, such assingspiel,opéra comique,operetta,andsemi-opera,the recitative is mostly replaced by spoken dialogue. Melodic or semi-melodic passages occurring in the midst of, or instead of, recitative, are also referred to asarioso.The terminology of the various kinds of operatic voices is described in detailbelow.[5]

During both theBaroqueandClassical periods,recitative could appear in two basic forms, each of which was accompanied by a different instrumental ensemble:secco(dry) recitative, sung with a free rhythm dictated by the accent of the words, accompanied only bybasso continuo,which was usually aharpsichordand a cello; oraccompagnato(also known asstrumentato) in which the orchestra provided accompaniment. Over the 18th century, arias were increasingly accompanied by the orchestra. By the 19th century,accompagnatohad gained the upper hand, the orchestra played a much bigger role, and Wagner revolutionized opera by abolishing almost all distinction between aria and recitative in his quest for what Wagner termed "endless melody". Subsequent composers have tended to followWagner's example, though some, such as Stravinsky in hisThe Rake's Progresshave bucked the trend. The changing role of the orchestra in opera is described in more detailbelow.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The Italian wordoperameans "work", both in the sense of the labour done and the result produced. The Italian word derives from the Latin wordopera,a singular noun meaning "work" and also the plural of the nounopus.According to theOxford English Dictionary,the Italian word was first used in the sense "composition in which poetry, dance, and music are combined" in 1639; the first recorded English usage in this sense dates to 1648.[6]

DafnebyJacopo Periwas the earliest composition considered opera, as understood today. It was written around 1597, largely under the inspiration of an elite circle of literateFlorentinehumanistswho gathered as the "Camerata de' Bardi".Significantly,Dafnewas an attempt to revive the classicalGreek drama,part of the wider revival of antiquity characteristic of theRenaissance.The members of the Camerata considered that the "chorus" parts of Greek dramas were originally sung, and possibly even the entire text of all roles; opera was thus conceived as a way of "restoring" this situation.Dafne,however, is lost. A later work by Peri,Euridice,dating from 1600, is the first opera score to have survived until the present day. However, the honour of being the first opera still to be regularly performed goes toClaudio Monteverdi'sL'Orfeo,composed for the court ofMantuain 1607.[7]The Mantua court of theGonzagas,employers of Monteverdi, played a significant role in the origin of opera employing not only court singers of theconcerto delle donne(till 1598), but also one of the first actual "opera singers",Madama Europa.[8]

Italian opera

[edit]Baroque era

[edit]

Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long. In 1637, the idea of a "season" (often during thecarnival) of publicly attended operas supported by ticket sales emerged inVenice.Monteverdi had moved to the city from Mantua and composed his last operas,Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patriaandL'incoronazione di Poppea,for the Venetian theatre in the 1640s. His most important followerFrancesco Cavallihelped spread opera throughout Italy. In these early Baroque operas, broad comedy was blended with tragic elements in a mix that jarred some educated sensibilities, sparking the first of opera's many reform movements, sponsored by theArcadian Academy,which came to be associated with the poetMetastasio,whoselibrettihelped crystallize the genre ofopera seria,which became the leading form of Italian opera until the end of the 18th century. Once the Metastasian ideal had been firmly established, comedy in Baroque-era opera was reserved for what came to be calledopera buffa.Before such elements were forced out of opera seria, many libretti had featured a separately unfolding comic plot as sort of an "opera-within-an-opera". One reason for this was an attempt to attract members of the growing merchant class, newly wealthy, but still not as cultured as the nobility, to the publicopera houses.These separate plots were almost immediately resurrected in a separately developing tradition that partly derived from thecommedia dell'arte,a long-flourishing improvisatory stage tradition of Italy. Just as intermedi had once been performed in between the acts of stage plays, operas in the new comic genre ofintermezzi,which developed largely inNaplesin the 1710s and 1720s, were initially staged during the intermissions of opera seria. They became so popular, however, that they were soon being offered as separate productions.

Opera seria was elevated in tone and highly stylised in form, usually consisting ofseccorecitative interspersed with longda capoarias. These afforded great opportunity for virtuosic singing and during the golden age ofopera seriathe singer really became the star. The role of the hero was usually written for the high-pitched malecastratovoice, which was produced bycastrationof the singer beforepuberty,which prevented a boy'slarynxfrom being transformed at puberty. Castrati such asFarinelliandSenesino,as well as femalesopranossuch asFaustina Bordoni,became in great demand throughout Europe asopera seriaruled the stage in every country except France. Farinelli was one of the most famous singers of the 18th century. Italian opera set the Baroque standard. Italian libretti were the norm, even when a German composer likeHandelfound himself composing the likes ofRinaldoandGiulio Cesarefor London audiences. Italianlibrettiremained dominant in theclassical periodas well, for example in the operas ofMozart,who wrote inViennanear the century's close. Leading Italian-born composers of opera seria includeAlessandro Scarlatti,Antonio VivaldiandNicola Porpora.[9]

Gluck's reforms and Mozart

[edit]

Opera seria had its weaknesses and critics. The taste for embellishment on behalf of the superbly trained singers, and the use of spectacle as a replacement for dramatic purity and unity drew attacks.Francesco Algarotti'sEssay on the Opera(1755) proved to be an inspiration forChristoph Willibald Gluck's reforms. He advocated thatopera seriahad to return to basics and that all the various elements—music (both instrumental and vocal),ballet,and staging—must be subservient to the overriding drama. In 1765Melchior Grimmpublished "Poème lyrique",an influential article for theEncyclopédieonlyricand operalibrettos.[10][11][12][13][14]Several composers of the period, includingNiccolò JommelliandTommaso Traetta,attempted to put these ideals into practice. The first to succeed however, was Gluck.Gluckstrove to achieve a "beautiful simplicity". This is evident in his first reform opera,Orfeo ed Euridice,where his non-virtuosic vocal melodies are supported by simple harmonies and a richer orchestra presence throughout.

Gluck's reforms have had resonance throughout operatic history. Weber, Mozart, and Wagner, in particular, were influenced by his ideals. Mozart, in many ways Gluck's successor, combined a superb sense of drama, harmony, melody, and counterpoint to write a series of comic operas with libretti byLorenzo Da Ponte,notablyLe nozze di Figaro,Don Giovanni,andCosì fan tutte,which remain among the most-loved, popular and well-known operas. But Mozart's contribution toopera seriawas more mixed; by his time it was dying away, and in spite of such fine works asIdomeneoandLa clemenza di Tito,he would not succeed in bringing the art form back to life again.[15]

Bel canto, Verdi and verismo

[edit]

Thebel cantoopera movement flourished in the early 19th century and is exemplified by the operas ofRossini,Bellini,Donizetti,Pacini,Mercadanteand many others. Literally "beautiful singing",bel cantoopera derives from the Italian stylistic singing school of the same name. Bel canto lines are typically florid and intricate, requiring supreme agility and pitch control. Examples of famous operas in the bel canto style include Rossini'sIl barbiere di SivigliaandLa Cenerentola,as well as Bellini'sNorma,La sonnambulaandI puritaniand Donizetti'sLucia di Lammermoor,L'elisir d'amoreandDon Pasquale.

Following the bel canto era, a more direct, forceful style was rapidly popularized byGiuseppe Verdi,beginning with his biblical operaNabucco.This opera, and the ones that would follow in Verdi's career, revolutionized Italian opera, changing it from merely a display of vocal fireworks, with Rossini's and Donizetti's works, to dramatic story-telling. Verdi's operas resonated with the growing spirit ofItalian nationalismin the post-Napoleonicera, and he quickly became an icon of the patriotic movement for a unified Italy. In the early 1850s, Verdi produced his three most popular operas:Rigoletto,Il trovatoreandLa traviata.The first of these,Rigoletto,proved the most daring and revolutionary. In it, Verdi blurs the distinction between the aria and recitative as it never before was, leading the opera to be "an unending string of duets".La traviatawas also novel. It tells the story of courtesan, and it includes elements ofverismoor "realistic" opera,[16]because rather than featuring great kings and figures from literature, it focuses on the tragedies of ordinary life and society. After these, he continued to develop his style, composing perhaps the greatest Frenchgrand opera,Don Carlos,and ending his career with twoShakespeare-inspiredworks,OtelloandFalstaff,which reveal how far Italian opera had grown in sophistication since the early 19th century. These final two works showed Verdi at his most masterfully orchestrated, and are both incredibly influential, and modern. InFalstaff,Verdi sets the pre-eminent standard for the form and style that would dominate opera throughout the twentieth century. Rather than long, suspended melodies,Falstaffcontains many little motifs and mottos, that, rather than being expanded upon, are introduced and subsequently dropped, only to be brought up again later. These motifs never are expanded upon, and just as the audience expects a character to launch into a long melody, a new character speaks, introducing a new phrase. This fashion of opera directed opera from Verdi, onward, exercising tremendous influence on his successorsGiacomo Puccini,Richard Strauss,andBenjamin Britten.[17]

After Verdi, the sentimental "realistic" melodrama ofverismoappeared in Italy. This was a style introduced byPietro Mascagni'sCavalleria rusticanaandRuggero Leoncavallo'sPagliaccithat came to dominate the world's opera stages with such popular works asGiacomo Puccini'sLa bohème,Tosca,andMadama Butterfly.Later Italian composers, such asBerioandNono,have experimented withmodernism.[18]

German-language opera

[edit]

The first German opera wasDafne,composed byHeinrich Schützin 1627, but the music score has not survived. Italian opera held a great sway over German-speaking countries until the late 18th century. Nevertheless, native forms would develop in spite of this influence. In 1644,Sigmund Stadenproduced the firstSingspiel,Seelewig,a popular form of German-language opera in which singing alternates with spoken dialogue. In the late 17th century and early 18th century, the Theater am Gänsemarkt inHamburgpresented German operas byKeiser,TelemannandHandel.Yet most of the major German composers of the time, including Handel himself, as well asGraun,Hasseand laterGluck,chose to write most of their operas in foreign languages, especially Italian. In contrast to Italian opera, which was generally composed for the aristocratic class, German opera was generally composed for the masses and tended to feature simple folk-like melodies, and it was not until the arrival of Mozart that German opera was able to match its Italian counterpart in musical sophistication.[19]The theatre company ofAbel Seylerpioneered serious German-language opera in the 1770s, marking a break with the previous simpler musical entertainment.[20][21]

Mozart'sSingspiele,Die Entführung aus dem Serail(1782) andDie Zauberflöte(1791) were an important breakthrough in achieving international recognition for German opera. The tradition was developed in the 19th century byBeethovenwith hisFidelio(1805), inspired by the climate of theFrench Revolution.Carl Maria von WeberestablishedGerman Romanticopera in opposition to the dominance of Italianbel canto.HisDer Freischütz(1821) shows his genius for creating a supernatural atmosphere. Other opera composers of the time includeMarschner,SchubertandLortzing,but the most significant figure was undoubtedlyWagner.

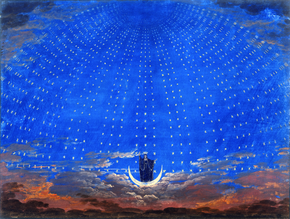

Wagner was one of the most revolutionary and controversial composers in musical history. Starting under the influence ofWeberandMeyerbeer,he gradually evolved a new concept of opera as aGesamtkunstwerk(a "complete work of art" ), a fusion of music, poetry and painting. He greatly increased the role and power of the orchestra, creating scores with a complex web ofleitmotifs,recurringthemesoften associated with the characters and concepts of the drama, of which prototypes can be heard in his earlier operas such asDer fliegende Holländer,TannhäuserandLohengrin;and he was prepared to violate accepted musical conventions, such astonality,in his quest for greater expressivity. In his mature music dramas,Tristan und Isolde,Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg,Der Ring des NibelungenandParsifal,he abolished the distinction between aria and recitative in favour of a seamless flow of "endless melody". Wagner also brought a new philosophical dimension to opera in his works, which were usually based on stories fromGermanicorArthurianlegend. Finally, Wagner builthis own opera houseatBayreuthwith part of the patronage fromLudwig II of Bavaria,exclusively dedicated to performing his own works in the style he wanted.

Opera would never be the same after Wagner and for many composers his legacy proved a heavy burden. On the other hand,Richard Straussaccepted Wagnerian ideas but took them in wholly new directions, along with incorporating the new form introduced by Verdi. He first won fame with the scandalousSalomeand the dark tragedyElektra,in which tonality was pushed to the limits. Then Strauss changed tack in his greatest success,Der Rosenkavalier,where Mozart and Viennesewaltzesbecame as important an influence as Wagner. Strauss continued to produce a highly varied body of operatic works, often with libretti by the poetHugo von Hofmannsthal.Other composers who made individual contributions to German opera in the early 20th century includeAlexander von Zemlinsky,Erich Korngold,Franz Schreker,Paul Hindemith,Kurt Weilland the Italian-bornFerruccio Busoni.The operatic innovations ofArnold Schoenbergand his successors are discussed in the section onmodernism.[22]

During the late 19th century, the Austrian composerJohann Strauss II,an admirer of theFrench-languageoperettascomposed byJacques Offenbach,composed several German-language operettas, the most famous of which wasDie Fledermaus.[23]Nevertheless, rather than copying the style of Offenbach, the operettas of Strauss II had distinctlyVienneseflavor to them.

French opera

[edit]

In rivalry with imported Italian opera productions, a separate French tradition was founded by the Italian-born French composerJean-Baptiste Lullyat the court ofKing Louis XIV.Despite his foreign birthplace, Lully established anAcademy of Musicand monopolised French opera from 1672. Starting withCadmus et Hermione,Lully and his librettistQuinaultcreatedtragédie en musique,a form in which dance music and choral writing were particularly prominent. Lully's operas also show a concern for expressiverecitativewhich matched the contours of the French language. In the 18th century, Lully's most important successor wasJean-Philippe Rameau,who composed fivetragédies en musiqueas well as numerous works in other genres such asopéra-ballet,all notable for their rich orchestration and harmonic daring. Despite the popularity of Italianopera seriathroughout much of Europe during the Baroque period, Italian opera never gained much of a foothold in France, where its own national operatic tradition was more popular instead.[24]After Rameau's death, the Bohemian-Austrian composerGluckwas persuaded to produce six operas for theParisian stagein the 1770s.[25]They show the influence of Rameau, but simplified and with greater focus on the drama. At the same time, by the middle of the 18th century another genre was gaining popularity in France:opéra comique.This was the equivalent of the Germansingspiel,where arias alternated with spoken dialogue. Notable examples in this style were produced byMonsigny,Philidorand, above all,Grétry.During theRevolutionaryandNapoleonicperiod, composers such asÉtienne Méhul,Luigi CherubiniandGaspare Spontini,who were followers of Gluck, brought a new seriousness to the genre, which had never been wholly "comic" in any case. Another phenomenon of this period was the 'propaganda opera' celebrating revolutionary successes, e.g.Gossec'sLe triomphe de la République(1793).

By the 1820s, Gluckian influence in France had given way to a taste for Italianbel canto,especially after the arrival ofRossiniinParis.Rossini'sGuillaume Tellhelped found the new genre ofgrand opera,a form whose most famous exponent was another foreigner,Giacomo Meyerbeer.Meyerbeer's works, such asLes Huguenots,emphasised virtuoso singing and extraordinary stage effects. Lighteropéra comiquealso enjoyed tremendous success in the hands ofBoïeldieu,Auber,HéroldandAdam.In this climate, the operas of the French-born composerHector Berliozstruggled to gain a hearing. Berlioz's epic masterpieceLes Troyens,the culmination of the Gluckian tradition, was not given a full performance for almost a hundred years.

In the second half of the 19th century,Jacques Offenbachcreatedoperettawith witty and cynical works such asOrphée aux enfers,as well as the operaLes Contes d'Hoffmann;Charles Gounodscored a massive success withFaust;andGeorges BizetcomposedCarmen,which, once audiences learned to accept its blend ofRomanticismand realism, became the most popular of all opéra comiques.Jules Massenet,Camille Saint-SaënsandLéo Delibesall composed works which are still part of the standard repertory, examples being Massenet'sManon,Saint-Saëns'Samson et Dalilaand Delibes'Lakmé.Their operas formed another genre, theopéra lyrique,combinedopéra comiqueand grand opera. It is less grandiose than grand opera, but without the spoken dialogue ofopèra comique.At the same time, the influence ofRichard Wagnerwas felt as a challenge to the French tradition. Many French critics angrily rejected Wagner's music dramas while many French composers closely imitated them with variable success. Perhaps the most interesting response came fromClaude Debussy.As in Wagner's works, the orchestra plays a leading role in Debussy's unique operaPelléas et Mélisande(1902) and there are no real arias, only recitative. But the drama is understated, Enigma tic and completely un-Wagnerian.

Other notable 20th-century names includeRavel,Dukas,Roussel,HoneggerandMilhaud.Francis Poulencis one of the very few post-war composers of any nationality whose operas (which includeDialogues des Carmélites) have gained a foothold in the international repertory.Olivier Messiaen's lengthy sacred dramaSaint François d'Assise(1983) has also attracted widespread attention.[26]

English-language opera

[edit]

In England, opera's antecedent was the 17th-centuryjig.This was an afterpiece that came at the end of a play. It was frequentlylibellousand scandalous and consisted in the main of dialogue set to music arranged from popular tunes. In this respect, jigs anticipate the ballad operas of the 18th century. At the same time, the Frenchmasquewas gaining a firm hold at the English Court, with even more lavish splendour and highly realistic scenery than had been seen before.Inigo Jonesbecame the quintessential designer of these productions, and this style was to dominate the English stage for three centuries. These masques contained songs and dances. InBen Jonson'sLovers Made Men(1617), "the whole masque was sung after the Italian manner, stilo recitativo".[27]The approach of theEnglish Commonwealthclosed theatres and halted any developments that may have led to the establishment of English opera. However, in 1656, thedramatistSirWilliam DavenantproducedThe Siege of Rhodes.Since his theatre was not licensed to produce drama, he asked several of the leading composers (Lawes,Cooke,Locke,ColemanandHudson) to set sections of it to music. This success was followed byThe Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru(1658) andThe History of Sir Francis Drake(1659). These pieces were encouraged byOliver Cromwellbecause they were critical of Spain. With theEnglish Restoration,foreign (especially French) musicians were welcomed back. In 1673,Thomas Shadwell'sPsyche,patterned on the 1671 'comédie-ballet' of the same name produced byMolièreandJean-Baptiste Lully.William DavenantproducedThe Tempestin the same year, which was the first musical adaption of aShakespeareplay (composed by Locke and Johnson).[27]About 1683,John BlowcomposedVenus and Adonis,often thought of as the first true English-language opera.

Blow's immediate successor was the better knownHenry Purcell.Despite the success of his masterworkDido and Aeneas(1689), in which the action is furthered by the use of Italian-style recitative, much of Purcell's best work was not involved in the composing of typical opera, but instead, he usually worked within the constraints of thesemi-operaformat, where isolated scenes and masques are contained within the structure of a spoken play, such asShakespearein Purcell'sThe Fairy-Queen(1692) and Beaumont and Fletcher inThe Prophetess(1690) andBonduca(1696). The main characters of the play tend not to be involved in the musical scenes, which means that Purcell was rarely able to develop his characters through song. Despite these hindrances, his aim (and that of his collaboratorJohn Dryden) was to establish serious opera in England, but these hopes ended with Purcell's early death at the age of 36.

Following Purcell, the popularity of opera in England dwindled for several decades. A revived interest in opera occurred in the 1730s which is largely attributed toThomas Arne,both for his own compositions and for alerting Handel to the commercial possibilities of large-scale works in English. Arne was the first English composer to experiment with Italian-style all-sung comic opera, with his greatest success beingThomas and Sallyin 1760. His operaArtaxerxes(1762) was the first attempt to set a full-blownopera seriain English and was a huge success, holding the stage until the 1830s. Although Arne imitated many elements of Italian opera, he was perhaps the only English composer at that time who was able to move beyond the Italian influences and create his own unique and distinctly English voice. His modernized ballad opera,Love in a Village(1762), began a vogue for pastiche opera that lasted well into the 19th century.Charles Burneywrote that Arne introduced "a light, airy, original, and pleasing melody, wholly different from that of Purcell or Handel, whom all English composers had either pillaged or imitated".

Besides Arne, the other dominating force in English opera at this time wasGeorge Frideric Handel,whoseopera seriasfilled the London operatic stages for decades and influenced most home-grown composers, likeJohn Frederick Lampe,who wrote using Italian models. This situation continued throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, including in the work ofMichael William Balfe,and the operas of the great Italian composers, as well as those of Mozart, Beethoven, and Meyerbeer, continued to dominate the musical stage in England.

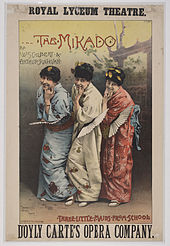

The only exceptions wereballad operas,such asJohn Gay'sThe Beggar's Opera(1728), musicalburlesques,Europeanoperettas,and lateVictorian eralight operas,notably theSavoy operasofW. S. GilbertandArthur Sullivan,all of which types of musical entertainments frequently spoofed operatic conventions; these genres contributed significantly to the emergence of the separate but closely related art ofmusical theatrein the late 19th century. Sullivan wrote only one grand opera,Ivanhoe(following the efforts of a number of young English composers beginning about 1876),[27]but he claimed that even his light operas constituted part of a school of "English" opera, intended to supplant the French operettas (usually performed in bad translations) that had dominated the London stage from the mid-19th century into the 1870s. London'sDaily Telegraphagreed, describingThe Yeomen of the Guardas "a genuine English opera, forerunner of many others, let us hope, and possibly significant of an advance towards a national lyric stage".[28]Sullivan produced a few light operas in the 1890s that were of a more serious nature than those in the G&S series, includingHaddon HallandThe Beauty Stone,butIvanhoe(which ran for 155 consecutive performances, using alternating casts—a record until Broadway'sLa bohème) survives as his onlygrand opera.

In the 20th century, English opera began to assert more independence, with works ofRalph Vaughan Williamsand in particularBenjamin Britten,who in a series of works that remain in standard repertory today, revealed an excellent flair for the dramatic and superb musicality. More recentlySir Harrison Birtwistlehas emerged as one of Britain's most significant contemporary composers from his first operaPunch and Judyto his most recent critical success inThe Minotaur.In the first decade of the 21st century, the librettist of an early Birtwistle opera,Michael Nyman,has been focusing on composing operas, includingFacing Goya,Man and Boy: Dada,andLove Counts.Today composers such asThomas Adèscontinue to export English opera abroad.[29]

Also in the 20th century, American composers likeGeorge Gershwin(Porgy and Bess),Scott Joplin(Treemonisha),Leonard Bernstein(Candide),Gian Carlo Menotti,Douglas Moore,andCarlisle Floydbegan to contribute English-language operas infused with touches of popular musical styles. They were followed by composers such asPhilip Glass(Einstein on the Beach),Mark Adamo,John Corigliano(The Ghosts of Versailles),Robert Moran,John Adams(Nixon in China),André PrevinandJake Heggie.Many contemporary 21st century opera composers have emerged such asMissy Mazzoli,Kevin Puts,Tom Cipullo,Huang Ruo,David T. Little,Terence Blanchard,Jennifer Higdon,Tobias Picker,Michael Ching,Anthony Davis,andRicky Ian Gordon.

Russian opera

[edit]

Opera was brought to Russia in the 1730s by theItalian operatictroupesand soon it became an important part of entertainment for the Russian Imperial Court andaristocracy.Many foreign composers such asBaldassare Galuppi,Giovanni Paisiello,Giuseppe Sarti,andDomenico Cimarosa(as well as various others) were invited to Russia to compose new operas, mostly in theItalian language.Simultaneously some domestic musicians of Ukrainian origin likeMaxim BerezovskyandDmitry Bortnianskywere sent abroad to learn to write operas. The first opera written in Russian wasTsefal i Prokrisby the Italian composerFrancesco Araja(1755). The development of Russian-language opera was supported by the Russian composersVasily Pashkevich,Yevstigney FominandAlexey Verstovsky.

However, the real birth ofRussian operacame withMikhail Glinkaand his two great operasA Life for the Tsar(1836) andRuslan and Lyudmila(1842). After him, during the 19th century in Russia, there were written such operatic masterpieces asRusalkaandThe Stone GuestbyAlexander Dargomyzhsky,Boris GodunovandKhovanshchinabyModest Mussorgsky,Prince IgorbyAlexander Borodin,Eugene OneginandThe Queen of SpadesbyPyotr Tchaikovsky,andThe Snow MaidenandSadkobyNikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.These developments mirrored the growth of Russiannationalismacross the artistic spectrum, as part of the more generalSlavophilismmovement.

In the 20th century, thetraditionsof Russian opera were developed by many composers includingSergei Rachmaninoffin his worksThe Miserly KnightandFrancesca da Rimini,Igor StravinskyinLe Rossignol,Mavra,Oedipus rex,andThe Rake's Progress,Sergei ProkofievinThe Gambler,The Love for Three Oranges,The Fiery Angel,Betrothal in a Monastery,andWar and Peace;as well asDmitri ShostakovichinThe NoseandLady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District,Edison DenisovinL'écume des jours,andAlfred SchnittkeinLife with an IdiotandHistoria von D. Johann Fausten.[30]

Czech opera

[edit]Czech composers also developed a thriving national opera movement of their own in the 19th century, starting withBedřich Smetana,who wroteeight operasincluding the internationally popularThe Bartered Bride.Smetana's eight operas created the bedrock of the Czech opera repertory, but of these onlyThe Bartered Brideis performed regularly outside the composer's homeland. After reaching Vienna in 1892 and London in 1895 it rapidly became part of the repertory of every major opera company worldwide.

Antonín Dvořák's nine operas, except his first, have librettos in Czech and were intended to convey the Czech national spirit, as were some of his choral works. By far the most successful of the operas isRusalkawhich contains the well-known aria "Měsíčku na nebi hlubokém" ( "Song to the Moon" ); it is played on contemporary opera stages frequently outside theCzech Republic.This is attributable to their uneven invention and libretti, and perhaps also their staging requirements –The Jacobin,Armida,VandaandDimitrijneed stages large enough to portray invading armies.

Leoš Janáčekgained international recognition in the 20th century for his innovative works. His later, mature works incorporate his earlier studies of national folk music in a modern, highly original synthesis, first evident in the operaJenůfa,which was premiered in 1904 inBrno.The success ofJenůfa(often called the "Moraviannational opera ") atPraguein 1916 gave Janáček access to the world's great opera stages. Janáček's later works are his most celebrated. They include operas such asKáťa KabanováandThe Cunning Little Vixen,theSinfoniettaand theGlagolitic Mass.

Other national operas

[edit]Spain also produced its own distinctive form of opera, known aszarzuela,which had two separate flowerings: one from the mid-17th century through the mid-18th century, and another beginning around 1850. During the late 18th century up until the mid-19th century, Italian opera was immensely popular in Spain, supplanting thenative form.

In Russian Eastern Europe, several national operas began to emerge. Ukrainian opera was developed bySemen Hulak-Artemovsky(1813–1873) whose most famous workZaporozhets za Dunayem(A Cossack Beyond the Danube) is regularly performed around the world. Other Ukrainian opera composers includeMykola Lysenko(Taras BulbaandNatalka Poltavka),Heorhiy Maiboroda,andYuliy Meitus.At the turn of the century, a distinct national opera movement also began to emerge inGeorgiaunder the leadershipZacharia Paliashvili,who fused localfolk songsand stories with 19th-centuryRomanticclassical themes.

The key figure of Hungarian national opera in the 19th century wasFerenc Erkel,whose works mostly dealt with historical themes. Among his most often performed operas areHunyadi LászlóandBánk bán.The most famous modern Hungarian opera isBéla Bartók'sDuke Bluebeard's Castle.

Stanisław Moniuszko's operaStraszny Dwór(in EnglishThe Haunted Manor) (1861–64) represents a nineteenth-century peak ofPolish national opera.[31]In the 20th century, other operas created by Polish composers includedKing RogerbyKarol SzymanowskiandUbu RexbyKrzysztof Penderecki.

The first known opera fromTurkey(theOttoman Empire) wasArshak II,which was anArmenianopera composed by an ethnic Armenian composerTigran Chukha gianin 1868 and partially performed in 1873. It was fully staged in 1945 in Armenia.

The first years of theSoviet Unionsaw the emergence of new national operas, such as theKoroğlu(1937) by theAzerbaijanicomposerUzeyir Hajibeyov.The firstKyrgyzopera,Ai-Churek,premiered in Moscow at theBolshoi Theatreon 26 May 1939, during Kyrgyz Art Decade. It was composed byVladimir Vlasov,Abdylas MaldybaevandVladimir Fere.The libretto was written by Joomart Bokonbaev, Jusup Turusbekov, and Kybanychbek Malikov. The opera is based on the Kyrgyz heroic epicManas.[32][33]

In Iran, opera gained more attention after the introduction of Western classical music in the late 19th century. However, it took until mid 20th century for Iranian composers to start experiencing with the field, especially as the construction of theRoudaki Hallin 1967, made possible staging of a large variety of works for stage. Perhaps, the most famous Iranian opera isRostam and SohrabbyLoris Tjeknavorianpremiered not until the early 2000s.

Chinese contemporary classical opera,a Chinese language form of Western style opera that is distinct fromtraditional Chinese opera,has had operas dating back toThe White-Haired Girlin 1945.[34][35][36]

In Latin America, opera started as a result of European colonisation. The first opera ever written in the Americas was 1701'sLa púrpura de la rosa,byTomás de Torrejón y Velasco,a Peruvian composer born in Spain; a decade later, 1711'sPartenope,by the MexicanManuel de Zumaya,was the first opera written from a composer born in Latin America (music now lost). The first Brazilian opera for a libretto in Portuguese wasA Noite de São João,byElias Álvares Lobo.However,Antônio Carlos Gomesis generally regarded as the most outstanding Brazilian composer, having a relative success in Italy with its Brazilian-themed operas with Italian librettos, such asIl Guarany.Opera in Argentina developed in the 20th century after the inauguration ofTeatro Colónin Buenos Aires—with the operaAurora,byEttore Panizza,being heavily influenced by the Italian tradition, due to immigration. Other important composers from Argentina includeFelipe BoeroandAlberto Ginastera.

Contemporary, recent, and modernist trends

[edit]Modernism

[edit]Perhaps the most obvious stylistic manifestation of modernism in opera is the development ofatonality.The move away from traditional tonality in opera had begun withRichard Wagner,and in particular theTristan chord.Composers such asRichard Strauss,Claude Debussy,Giacomo Puccini,[37]Paul Hindemith,Benjamin BrittenandHans Pfitznerpushed Wagnerian harmony further with a more extreme use of chromaticism and greater use of dissonance. Another aspect of modernist opera is the shift away from long, suspended melodies, to short quick mottos, as first illustrated byGiuseppe Verdiin hisFalstaff.Composers such as Strauss, Britten, Shostakovich and Stravinsky adopted and expanded upon this style.

Operatic modernism truly began in the operas of two Viennese composers,Arnold Schoenbergand his studentAlban Berg,both composers and advocates of atonality and its later development (as worked out by Schoenberg),dodecaphony.Schoenberg's early musico-dramatic works,Erwartung(1909, premiered in 1924) andDie glückliche Handdisplay heavy use of chromatic harmony and dissonance in general. Schoenberg also occasionally usedSprechstimme.

The two operas of Schoenberg's pupil Alban Berg,Wozzeck(1925) andLulu(incomplete at his death in 1935) share many of the same characteristics as described above, though Berg combined his highly personal interpretation of Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique with melodic passages of a more traditionally tonal nature (quite Mahlerian in character) which perhaps partially explains why his operas have remained in standard repertory, despite their controversial music and plots. Schoenberg's theories have influenced (either directly or indirectly) significant numbers of opera composers ever since, even if they themselves did not compose using his techniques.

Composers thus influenced include the EnglishmanBenjamin Britten,the GermanHans Werner Henze,and the RussianDmitri Shostakovich.(Philip Glassalso makes use of atonality, though his style is generally described asminimalist,usually thought of as another 20th-century development.)[38]

However, operatic modernism's use of atonality also sparked a backlash in the form ofneoclassicism.An early leader of this movement wasFerruccio Busoni,who in 1913 wrote the libretto for his neoclassicalnumber operaArlecchino(first performed in 1917).[39]Also among the vanguard was the RussianIgor Stravinsky.After composing music for theDiaghilev-produced balletsPetrushka(1911) andThe Rite of Spring(1913), Stravinsky turned to neoclassicism, a development culminating in his opera-oratorioOedipus rex(1927). Stravinsky had already turned away from the modernist trends of his early ballets to produce small-scale works that do not fully qualify as opera, yet certainly contain many operatic elements, includingRenard(1916: "a burlesque in song and dance" ) andThe Soldier's Tale(1918: "to be read, played, and danced"; in both cases the descriptions and instructions are those of the composer). In the latter, the actors declaim portions of speech to a specified rhythm over instrumental accompaniment, peculiarly similar to the older German genre ofMelodrama.Well after his Rimsky-Korsakov-inspired worksThe Nightingale(1914), andMavra(1922), Stravinsky continued to ignoreserialist techniqueand eventually wrote a full-fledged 18th-century-stylediatonicnumber operaThe Rake's Progress(1951). His resistance to serialism (an attitude he reversed following Schoenberg's death) proved to be an inspiration for many[who?]other composers.[40]

Other trends

[edit]A common trend throughout the 20th century, in both opera and general orchestral repertoire, is the use of smaller orchestras as a cost-cutting measure; the grand Romantic-era orchestras with huge string sections, multiple harps, extra horns, and exotic percussion instruments were no longer feasible. As government and private patronage of the arts decreased throughout the 20th century, new works were often commissioned and performed with smaller budgets, very often resulting in chamber-sized works, and short, one-act operas. Many ofBenjamin Britten's operas are scored for as few as 13 instrumentalists;Mark Adamo's two-act realization ofLittle Womenis scored for 18 instrumentalists.

Another feature of late 20th-century opera is the emergence of contemporary historical operas, in contrast to the tradition of basing operas on more distant history, the re-telling of contemporary fictional stories or plays, or on myth or legend.The Death of Klinghoffer,Nixon in China,andDoctor AtomicbyJohn Adams,Dead Man WalkingbyJake Heggie,Anna NicolebyMark-Anthony Turnage,andWaiting for Miss Monroe[41]byRobin de Raaffexemplify the dramatisation onstage of events in recent living memory, where characters portrayed in the opera were alive at the time of the premiere performance.

TheMetropolitan Operain the US (often known as the Met) reported in 2011 that the average age of its audience was 60.[42]Many opera companies attempted to attract a younger audience to halt the larger trend of greying audiences forclassical musicsince the last decades of the 20th century.[43]Efforts resulted in lowering the average age of the Met's audience to 58 in 2018, the average age atBerlin State Operawas reported as 54, andParis Operareported an average age of 48.[44]New York TimescriticAnthony Tommasinihas suggested that "companies inordinately beholden to standard repertory" are not reaching younger, more curious audiences.[45]

Smaller companies in the US have a more fragile existence, and they usually depend on a "patchwork quilt" of support from state and local governments, local businesses, and fundraisers. Nevertheless, some smaller companies have found ways of drawing new audiences. In addition to radio and television broadcasts of opera performances, which have had some success in gaining new audiences, broadcasts of live performances to movie theatres have shown the potential to reach new audiences.[46]

From musicals back towards opera

[edit]By the late 1930s, somemusicalsbegan to be written with a more operatic structure. These works include complex polyphonic ensembles and reflect musical developments of their times.Porgy and Bess(1935), influenced by jazz styles, andCandide(1956), with its sweeping, lyrical passages and farcical parodies of opera, both opened onBroadwaybut became accepted as part of the opera repertory. Popular musicals such asShow Boat,West Side Story,Brigadoon,Sweeney Todd,Passion,Evita,The Light in the Piazza,The Phantom of the Operaand others tell dramatic stories through complex music and in the 2010s they are sometimes seen in opera houses.[47]The Most Happy Fella(1952) is quasi-operatic and has been revived by theNew York City Opera.Otherrock-influenced musicals,such asTommy(1969) andJesus Christ Superstar(1971),Les Misérables(1980),Rent(1996),Spring Awakening(2006), andNatasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812(2012) employ various operatic conventions, such asthrough composition,recitative instead of dialogue, andleitmotifs.

Acoustic enhancement in opera

[edit]A subtle type of sound electronic reinforcement calledacoustic enhancementis used in some modern concert halls and theatres where operas are performed. Although none of the major opera houses "...use traditional, Broadway-style sound reinforcement, in which most if not all singers are equipped with radio microphones mixed to a series of unsightly loudspeakers scattered throughout the theatre", many use asound reinforcement systemfor acoustic enhancement and for subtle boosting of offstage voices, child singers, onstage dialogue, and sound effects (e.g., church bells inToscaor thunder effects in Wagnerian operas).[48]

Operatic voices

[edit]Operatic vocal technique evolved, in a time before electronic amplification, to allow singers to produce enough volume to be heard over an orchestra, without the instrumentalists having to substantially compromise their volume.

Vocal classifications

[edit]Singers and the roles they play are classified byvoice type,based on thetessitura,agility, powerandtimbreof their voices. Male singers can be classified byvocal rangeasbass,bass-baritone,baritone,baritenor,tenorandcountertenor,and female singers ascontralto,mezzo-sopranoandsoprano.(Men sometimes sing in the "female" vocal ranges, in which case they are termedsopranistor countertenor. The countertenor is commonly encountered in opera, sometimes singing parts written forcastrati—men neutered at a young age specifically to give them a higher singing range.) Singers are then further classified by size—for instance, a soprano can be described as a lyric soprano,coloratura,soubrette,spinto,or dramatic soprano. These terms, although not fully describing a singing voice, associate the singer's voice with the roles most suitable to the singer's vocal characteristics.

Yet another sub-classification can be made according to acting skills or requirements, for example thebasso buffowho often must be a specialist inpatteras well as a comic actor. This is carried out in detail in theFachsystem of German speaking countries, where historically opera and spokendramawere often put on by the samerepertorycompany.

A particular singer's voice may change drastically over his or her lifetime, rarely reaching vocal maturity until the third decade, and sometimes not until middle age. Two French voice types,premiere dugazonanddeuxieme dugazon,were named after successive stages in the career ofLouise-Rosalie Lefebvre(Mme. Dugazon). Other terms originating in the star casting system of theParisian theatresarebaryton-martinandsopranofalcon.

Historical use of voice parts

[edit]- The following is only intended as a brief overview. For the main articles, seesoprano,mezzo-soprano,contralto,tenor,baritone,bass,countertenorandcastrato.

The soprano voice has typically been used as the voice of choice for the female protagonist of the opera since the latter half of the 18th century. Earlier, it was common for that part to be sung by any female voice, or even acastrato.The current emphasis on a wide vocal range was primarily an invention of theClassical period.Before that, the vocal virtuosity, not range, was the priority, with soprano parts rarely extending above a highA(Handel,for example, only wrote one role extending to a highC), though the castratoFarinelliwas alleged to possess a topD(his lower range was also extraordinary, extending to tenor C). The mezzo-soprano, a term of comparatively recent origin, also has a large repertoire, ranging from the female lead in Purcell'sDido and Aeneasto such heavyweight roles as Brangäne in Wagner'sTristan und Isolde(these are both roles sometimes sung by sopranos; there is quite a lot of movement between these two voice-types). For the true contralto, the range of parts is more limited, which has given rise to the insider joke that contraltos only sing "witches, bitches, andbritches"roles. In recent years many of the" trouser roles "from the Baroque era, originally written for women, and those originally sung by castrati, have been reassigned to countertenors.

The tenor voice, from the Classical era onwards, has traditionally been assigned the role of male protagonist. Many of the most challenging tenor roles in the repertory were written during thebel cantoera, such asDonizetti's sequence of 9 Cs above middle C duringLa fille du régiment.With Wagner came an emphasis on vocal heft for his protagonist roles, with this vocal category described asHeldentenor;this heroic voice had its more Italianate counterpart in such roles as Calaf in Puccini'sTurandot.Basses have a long history in opera, having been used inopera seriain supporting roles, and sometimes for comic relief (as well as providing a contrast to the preponderance of high voices in this genre). The bass repertoire is wide and varied, stretching from the comedy of Leporello inDon Giovannito the nobility of Wotan inWagner'sRing Cycle,to the conflicted King Phillip of Verdi'sDon Carlos.In between the bass and the tenor is the baritone, which also varies in weight from say, Guglielmo in Mozart'sCosì fan tutteto Posa in Verdi'sDon Carlos;the actual designation "baritone" was not standard until the mid-19th century.

Famous singers

[edit]

Early performances of opera were too infrequent for singers to make a living exclusively from the style, but with the birth of commercial opera in the mid-17th century, professional performers began to emerge. The role of the male hero was usually entrusted to acastrato,and by the 18th century, when Italian opera was performed throughout Europe, leading castrati who possessed extraordinary vocal virtuosity, such asSenesinoandFarinelli,became international stars. The career of the first major female star (orprima donna),Anna Renzi,dates to the mid-17th century. In the 18th century, a number of Italian sopranos gained international renown and often engaged in fierce rivalry, as was the case withFaustina BordoniandFrancesca Cuzzoni,who started a fistfight with one another during a performance of a Handel opera. The French disliked castrati, preferring their male heroes to be sung by anhaute-contre(a high tenor), of whichJoseph Legros(1739–1793) was a leading example.[49]

Though opera patronage has decreased in the last century in favor of other arts and media (such as musicals, cinema, radio, television and recordings), mass media and the advent of recording have supported the popularity of many famous singers includingAnna Netrebko,Maria Callas,Enrico Caruso,Amelita Galli-Curci,Kirsten Flagstad,Mario Del Monaco,Renata Tebaldi,Risë Stevens,Alfredo Kraus,Franco Corelli,Montserrat Caballé,Joan Sutherland,Birgit Nilsson,Nellie Melba,Rosa Ponselle,Beniamino Gigli,Jussi Björling,Feodor Chaliapin,Cecilia Bartoli,Elena Obraztsova,Renée Fleming,Galina Vishnevskaya,Marilyn Horne,Bryn Terfel,Dmitri HvorostovskyandThe Three Tenors(Luciano Pavarotti,Plácido Domingo,José Carreras).

Changing role of the orchestra

[edit]Before the 1700s, Italian operas used a smallstring orchestra,but it rarely played to accompany the singers. Opera solos during this period were accompanied by thebasso continuogroup, which consisted of theharpsichord,"plucked instruments" such asluteand a bass instrument.[50]The string orchestra typically only played when the singer was not singing, such as during a singer's "...entrances and exits, between vocal numbers, [or] for [accompanying] dancing". Another role for the orchestra during this period was playing an orchestralritornelloto mark the end of a singer's solo.[50]During the early 1700s, some composers began to use the string orchestra to mark certain aria or recitatives "...as special"; by 1720, most arias were accompanied by an orchestra. Opera composers such asDomenico Sarro,Leonardo Vinci,Giambattista Pergolesi,Leonardo Leo,andJohann Adolph Hasseadded new instruments to the opera orchestra and gave the instruments new roles. They added wind instruments to the strings and used orchestral instruments to play instrumental solos, as a way to mark certain arias as special.[50]

The orchestra has also provided an instrumentaloverturebefore the singers come onstage since the 1600s.Peri'sEuridiceopens with a brief instrumentalritornello,andMonteverdi'sL'Orfeo(1607) opens with atoccata,in this case a fanfare for mutedtrumpets.TheFrench overtureas found inJean-Baptiste Lully's operas[51]consist of a slow introduction in a marked "dotted rhythm", followed by a lively movement infugatostyle. The overture was frequently followed by a series of dance tunes before the curtain rose. This overture style was also used in English opera, most notably inHenry Purcell'sDido and Aeneas.Handelalso uses the French overture form in some of his Italian operas such asGiulio Cesare.[52]

In Italy, a distinct form called "overture" arose in the 1680s, and became established particularly through the operas ofAlessandro Scarlatti,and spread throughout Europe, supplanting the French form as the standard operatic overture by the mid-18th century.[53]It uses three generallyhomophonicmovements:fast–slow–fast. The opening movement was normally in duple metre and in a major key; the slow movement in earlier examples was short, and could be in a contrasting key; the concluding movement was dance-like, most often with rhythms of thegigueorminuet,and returned to the key of the opening section. As the form evolved, the first movement may incorporate fanfare-like elements and took on the pattern of so-called "sonatina form" (sonata formwithout a development section), and the slow section became more extended and lyrical.[53]

In Italian opera after about 1800, the "overture" became known as thesinfonia.[54]Fisher also notes the termSinfonia avanti l'opera(literally, the "symphony before the opera" ) was "an early term for a sinfonia used to begin an opera, that is, as an overture as opposed to one serving to begin a later section of the work".[54]In 19th-century opera, in some operas, the overture,Vorspiel,Einleitung,Introduction, or whatever else it may be called, was the portion of the music which takes place before the curtain rises; a specific, rigid form was no longer required for the overture.

The role of the orchestra in accompanying the singers changed over the 19th century, as the Classical style transitioned to the Romantic era. In general, orchestras got bigger, new instruments were added, such as additional percussion instruments (e.g., bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, etc.). Theorchestrationof orchestra parts also developed over the 19th century. In Wagnerian operas, the forefronting of the orchestra went beyond the overture. In Wagnerian operas such as theRing Cycle,the orchestra often played the recurrent musical themes orleitmotifs,a role which gave a prominence to the orchestra which "...elevated its status to that of aprima donna".[55]Wagner's operas were scored with unprecedented scope and complexity, adding morebrass instrumentsand huge ensemble sizes: indeed, his score toDas Rheingoldcalls for sixharps.In Wagner and the work of subsequent composers, such as Benjamin Britten, the orchestra "often communicates facts about the story that exceed the levels of awareness of the characters therein. As a result, critics began to regard the orchestra as performing a role analogous to that of a literary narrator."[56]

As the role of the orchestra and other instrumental ensembles changed over the history of opera, so did the role of leading the musicians. In the Baroque era, the musicians were usually directed by the harpsichord player, although the French composer Lully is known to have conducted with a long staff. In the 1800s, during the Classical period, the first violinist, also known as theconcertmaster,would lead the orchestra while sitting. Over time, some directors began to stand up and use hand and arm gestures to lead the performers. Eventually this role ofmusic directorbecame termed theconductor,and a podium was used to make it easier for all the musicians to see him or her. By the time Wagnerian operas were introduced, the complexity of the works and the huge orchestras used to play them gave the conductor an increasingly important role. Modern opera conductors have a challenging role: they have to direct both the orchestra in theorchestra pitand the singers on stage.

Language and translation issues

[edit]Since the days of Handel and Mozart, many composers have favored Italian as the language for the libretto of their operas. From the Bel Canto era to Verdi, composers would sometimes supervise versions of their operas in both Italian and French. Because of this, operas such asLucia di LammermoororDon Carlosare today deemed canonical in both their French and Italian versions.[57]

Until the mid-1950s, it was acceptable to produce operas in translations even if these had not been authorized by the composer or the original librettists. For example, opera houses in Italy routinely staged Wagner in Italian.[58]After World War II, opera scholarship improved, artists refocused on the original versions, and translations fell out of favor. Knowledge of European languages, especially Italian, French, and German, is today an important part of the training for professional singers. "The biggest chunk of operatic training is in linguistics and musicianship", explains mezzo-sopranoDolora Zajick."[I have to understand] not only what I'm singing, but what everyone else is singing. I sing Italian, Czech, Russian, French, German, English."[59]

In the 1980s, supertitles (sometimes calledsurtitles) began to appear. Although supertitles were first almost universally condemned as a distraction,[60]today many opera houses provide either supertitles, generally projected above the theatre'sprosceniumarch, or individual seat screens where spectators can choose from more than one language. TV broadcasts typically include subtitles even if intended for an audience who knows well the language (for example, aRAIbroadcast of an Italian opera). These subtitles target not only the hard of hearing but the audience generally, since a sung discourse is much harder to understand than a spoken one—even in the ears of native speakers. Subtitles in one or more languages have become standard in opera broadcasts, simulcasts, and DVD editions.

Today, operas are only rarely performed in translation. Exceptions include theEnglish National Opera,theOpera Theatre of Saint Louis,Opera Theater of Pittsburgh,and Opera South East,[61]which favor English translations.[62]Another exception are opera productions intended for a young audience, such as Humperdinck'sHansel and Gretel[63]and some productions of Mozart'sThe Magic Flute.[64]

Funding

[edit]

Outside the US, and especially in Europe, most opera houses receive public subsidies from taxpayers.[65]In Milan, Italy, 60% of La Scala's annual budget of €115 million is from ticket sales and private donations, with the remaining 40% coming from public funds.[66]In 2005, La Scala received 25% of Italy's total state subsidy of €464 million for the performing arts.[67]In the UK,Arts Council Englandprovides funds toOpera North,theRoyal Opera House,Welsh National Opera,andEnglish National Opera.Between 2012 and 2015, these four opera companies along with theEnglish National Ballet,Birmingham Royal BalletandNorthern Balletaccounted for 22% of the funds in the Arts Council's national portfolio. During that period, the Council undertook an analysis of its funding for large-scale opera and ballet companies, setting recommendations and targets for the companies to meet prior to the 2015–2018 funding decisions.[68]In February 2015, concerns over English National Opera's business plan led to the Arts Council placing it "under special funding arrangements" in whatThe Independenttermed "the unprecedented step" of threatening to withdraw public funding if the council's concerns were not met by 2017.[69]European public funding to opera has led to a disparity between the number of year-round opera houses in Europe and the United States. For example, "Germany has about 80 year-round opera houses [as of 2004], while the U.S., with more than three times the population, does not have any. Even the Met only has a seven-month season."[70]

Television, cinema and the Internet

[edit]

A milestone for opera broadcasting in the U.S. was achieved on 24 December 1951, with the live broadcast ofAmahl and the Night Visitors,an opera in one act byGian Carlo Menotti.It was the firstopera specifically composed for televisionin America.[71]Another milestone occurred in Italy in 1992 whenToscawas broadcast live from its original Roman settings and times of the day: the first act came from the 16th-century Church of Sant'Andrea della Valle at noon on Saturday; the 16th-century Palazzo Farnese was the setting for the second at 8:15 pm; and on Sunday at 6 am, the third act was broadcast from Castel Sant'Angelo. The production was transmitted via satellite to 105 countries.[72]

Major opera companies have begun presenting their performances in local cinemas throughout the United States and many other countries. The Metropolitan Opera began aseriesof livehigh-definition videotransmissions to cinemas around the world in 2006.[73]In 2007, Met performances were shown in over 424 theaters in 350 U.S. cities.La bohèmewent out to 671 screens worldwide.San Francisco Operabegan prerecorded video transmissions in March 2008. As of June 2008, approximately 125 theaters in 117 U.S. cities carry the showings. The HD video opera transmissions are presented via the sameHD digital cinema projectorsused for majorHollywood films.[74]European opera houses andfestivalsincludingThe Royal Operain London,La Scalain Milan, theSalzburg Festival,La Fenicein Venice, and theMaggio Musicalein Florence have also transmitted their productions to theaters in cities around the world since 2006, including 90 cities in the U.S.[75][76]

The emergence of the Internet has also affected the way in which audiences consume opera. In 2009 the BritishGlyndebourne Festival Operaoffered for the first time an online digital video download of its complete 2007 production ofTristan und Isolde.In the 2013 season, the festivalstreamedall six of its productions online.[77][78]In July 2012, the firstonline communityopera was premiered at theSavonlinna Opera Festival.TitledFree Will,it was created by members of the Internet group Opera By You. Its 400 members from 43 countries wrote the libretto, composed the music, and designed the sets and costumes using theWreckamovieweb platform. Savonlinna Opera Festival provided professional soloists, an 80-member choir, a symphony orchestra, and the stage machinery. It was performed live at the festival and streamed live on the internet.[79]

See also

[edit]| Part ofa serieson |

| Performing arts |

|---|

- Lists of operas,including ageneral listas well as bytheme,bycountry,bymedium,and byvenue

- List of fictional literature featuring opera

- Opera management

- Radio opera

- Chronological list of operatic sopranos

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Richard WagnerandArrigo Boitoare notable creators who combined both roles.

- ^Some definitions of opera: "dramatic performance or composition of which music is an essential part, branch of art concerned with this" (Concise Oxford English Dictionary); "any dramatic work that can be sung (or at times declaimed or spoken) in a place for performance, set to original music for singers (usually in costume) and instrumentalists" (Amanda Holden,Viking Opera Guide); "musical work for the stage with singing characters, originated in early years of 17th century" (Pears' Cyclopaedia,1983 ed.).

- ^Comparable art forms from various other parts of the world, many of them ancient in origin, are also sometimes called "opera" by analogy, usually prefaced with an adjective indicating the region (for example,Chinese opera). These independent traditions are not derivative of Western opera but are rather distinct forms ofmusical theatre.Opera is also not the only type of Western musical theatre: in the ancient world,Greek dramafeatured singing and instrumental accompaniment; and in modern times, other forms such as themusicalhave appeared.

- ^abApel 1969,p. 718

- ^General information in this section comes from the relevant articles inThe Oxford Companion to Music,byP. Scholes(10th ed., 1968).

- ^Oxford English Dictionary,3rd ed., s.v. "operaArchived3 July 2023 at theWayback Machine".

- ^Parker 1994,ch. 1; articles on Peri and Monteverdi inThe Viking Opera Guide.

- ^Karin Pendle,Women and Music,2001, p. 65: "From 1587–1600 a Jewish singer cited only as Madama Europa was in the pay of the Duke of Mantua,"

- ^Parker 1994,ch. 1–3.

- ^"Melchior baron de Grimm".Encyclopédie Larousse en ligne(in French).Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^Thomas, Downing A (15 June 1995).Music and the Origins of Language: Theories from the French Enlightenment.Cambridge University Press. p. 148.ISBN978-0-521-47307-1.

- ^Heyer, John Hajdu (7 December 2000).Lully Studies.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-62183-0– via Google Books.

- ^Lippman, Edward A. (26 November 1992).A History of Western Musical Aesthetics.U of Nebraska Press.ISBN978-0-8032-7951-3– via Google Books.

- ^"King's College London – Seminar 1".kcl.ac.uk.Archived fromthe originalon 18 November 2018.Retrieved10 April2014.

- ^Man and Music: the Classical Era,ed.Neal Zaslaw(Macmillan, 1989); entries on Gluck and Mozart inThe Viking Opera Guide.

- ^Morgan, Ann Shands (August 1968).Elements of Verismo in Selected Operas of Giuseppe Verdi(Master of Musicthesis). Denton, Texas:University of North Texas Libraries.Retrieved31 October2023.

- ^"Strauss and Wagner – Various articles – Richard Strauss".richardstrauss.at.Archivedfrom the original on 14 July 2016.Retrieved15 July2016.

- ^Parker 1994,ch. 5, 8,9;Viking Opera Guideentry on Verdi.

- ^Man and Music: the Classical Eraed.Neal Zaslaw(Macmillan, 1989), pp. 242–247, 258–260;Parker 1994,pp. 58–63, 98–103. Articles on Hasse, Graun and Hiller inViking Opera Guide.

- ^Francien Markx,E. T. A. Hoffmann, Cosmopolitanism, and the Struggle for German Opera,p. 32, BRILL, 2015,ISBN9004309578

- ^Thomas Bauman,"New directions: the Seyler Company" (pp. 91–131), inNorth German Opera in the Age of Goethe,Cambridge University Press, 1985

- ^General outline for this section fromParker 1994,chapters 1–3, 6, 8 and 9, andThe Oxford Companion to Music;more specific references from the individual composer entries inThe Viking Opera Guide.

- ^Kenrick, John.A History of The Musical: European Operetta 1850–1880Archived5 May 2012 at theWayback Machine.Musicals101

- ^Grout, Donald Jay;Williams, Hermine Weigel (2003).A Short History of Opera.Columbia University Press. p.133.ISBN978-0-231-11958-0.Retrieved11 April2014.

- ^Hayes, Jeremy; Brown, Bruce Alan; Loppert, Max; Dean, Winton (2022). "Gluck, Christoph Willibald Ritter von".Grove Music Online(8th ed.).Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.O007318.ISBN978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^General outline for this section fromParker 1994,chapters 1–4, 8 and 9; andThe Oxford Companion to Music(10th ed., 1968); more specific references from the individual composer entries inThe Viking Opera Guide.

- ^abcFrom Webrarian 'sArchived27 September 2007 at theWayback MachineIvanhoesite.

- ^TheDaily Telegraph's review ofYeomenstated, "The accompaniments... are delightful to hear, and especially does the treatment of the woodwind compel admiring attention. Schubert himself could hardly have handled those instruments more deftly....we have a genuine English opera, forerunner of many others, let us hope, and possibly significant of an advance towards a national lyric stage." (quoted at p. 312 in Allen, Reginald (1975).The First Night Gilbert and Sullivan.London: Chappell & Co. Ltd.).

- ^Parker 1994,ch. 1, 3, 9.The Viking Opera Guidearticles on Blow, Purcell and Britten.

- ^Taruskin, Richard:"Russia" inThe New Grove Dictionary of Opera,ed.Stanley Sadie(London, 1992);Parker 1994,ch. 7–9

- ^Tyrrell 1994,p. 246.

- ^Abazov, Rafis (2007).Culture and Customs of the Central Asian RepublicsArchived3 July 2023 at theWayback Machine,pp. 144–145. Greenwood Publishing Group,ISBN0-313-33656-3

- ^Igmen, Ali F. (2012).Speaking Soviet with an Accent.University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 163.ISBN978-0-8229-7809-1.

- ^Rubin, Don; Chua, Soo Pong; Chaturvedi, Ravi; Majundar, Ramendu; Tanokura, Minoru, eds. (2001). "China".World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre – Asia/Pacific.Vol. 5. p. 111.

Western-style opera (also known as High Opera) exists alongside the many Beijing Opera groups.... Operas of note by Chinese composers includeA Girl With White Hairwritten in the 1940s,Red Squad in Hong HuandJiang Jie.

- ^Zicheng Hong,A History of Contemporary Chinese Literature,2007, p. 227: "Written in the early 1940s, for a long timeThe White-Haired Girlwas considered a model of new western-style opera in China. "

- ^Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women,vol. 2, p. 145, Lily Xiao Hong Lee, A. D. Stefanowska, Sue Wiles (2003) "... of the PRC,Zheng Lüchengwas active in his work as a composer; he wrote the music for the Western-style operaCloud Gazing."

- ^Scott, Derek B. (1998). "Orientalism and Musical Style".The Musical Quarterly.82(2): 323.doi:10.1093/mq/82.2.309.JSTOR742411.

- ^"Minimalist music: where to start".Classic FM.Archivedfrom the original on 13 February 2020.Retrieved15 December2019.

- ^Chris Walton, "Neo-classical opera" inCooke 2005,p. 108

- ^Parker 1994,ch. 8;The Viking Opera Guidearticles on Schoenberg, Berg and Stravinsky;Malcolm MacDonald,Schoenberg(Dent, 1976);Francis Routh,Stravinsky(Dent, 1975).

- ^George Loomis (12 June 2012)."A Dutch Take on a Cultural Icon".Retrieved8 December2023.

- ^Wakin, Daniel J. (17 February 2011)."Met Backtracks on Drop in Average Audience Age".The New York Times.Archived fromthe originalon 4 February 2021.

- ^General reference for this section:Parker 1994,ch. 9

- ^Grey, Tobias (19 February 2018)."An Unlikely Youth Revolution at the Paris Opera".The New York Times.Archived fromthe originalon 11 February 2021.

- ^Tommasini, Anthony(6 August 2020)."Classical Music Attracts Older Audiences. Good".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 30 November 2022.Retrieved30 November2022.

- ^"On Air & On Line".The Metropolitan Opera. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 20 November 2007.Retrieved4 March2021.

- ^Clements, Andrew (17 December 2003)."Sweeney Todd,Royal Opera House, London ".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2017.Retrieved15 December2016.

- ^Harada, Kai (1 March 2001)."Opera's Dirty Little Secret".Live Design.Archived fromthe originalon 13 February 2012.

- ^Parker 1994,ch. 11.

- ^abcJohn Spitzer. (2009). Orchestra and voice in eighteenth-century Italian opera. In: Anthony R. DelDonna and Pierpaolo Polzonetti (eds.)The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Opera.pp. 112–139. [Online]. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^Waterman, George Gow, and James R. Anthony. 2001. "French Overture".The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians,second edition, edited byStanley SadieandJohn Tyrrell.London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^Burrows, Donald (2012).Handel.Oxford University Press. p. 178.ISBN978-0-19-973736-9.Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2023.Retrieved7 September2018.

- ^abFisher, Stephen C. 2001. "Italian Overture."The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians,second edition, edited byStanley SadieandJohn Tyrrell.London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^abFisher, Stephen C. 1998. "Sinfonia".The New Grove Dictionary of Opera,four volumes, edited byStanley Sadie.London: Macmillan Publishers, Inc.ISBN0-333-73432-7

- ^Murray, Christopher John (2004).Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era.Taylor & Francis. p. 772.

- ^Penner, Nina (2020).Storytelling in Opera and Musical Theater.Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 89.ISBN9780253049971.

- ^de Acha, Rafael."Don Carlo or Don Carlos? In Italian or in French?"(Seen and Heard International, 24 September 2013).Archived21 October 2017 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Lyndon Terracini(11 April 2011)."Whose language is opera: the audience's or the composer's?".The Australian.Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2017.Retrieved13 April2018.

- ^"For Opera Powerhouse Dolora Zajick, 'Singing Is Connected To The Body'"(Fresh Air, NPR, 19 March 2014).Archived26 April 2015 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Tommasini, Anthony."So That's What the Fat Lady Sang"Archived18 March 2017 at theWayback Machine(The New York Times,6 July 2008)

- ^"Opera South East's past productions back to 1980... OSE has always sung its operatic productions in English, fully staged and with orchestra (the acclaimed Sussex Concert Orchestra)."Archived18 March 2017 at theWayback Machine(Opera South East website's history of ProAm past productions)

- ^Tommasini, Anthony."Opera in Translation Refuses to Give Up the Ghost"Archived7 July 2017 at theWayback Machine(The New York Times,25 May 2001)

- ^Eddins, Stephen."Humperdinck'sHansel & Gretel:A Review ".AllMusic.Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2014.Retrieved3 June2014.

- ^Tommasini, Anthony."A Mini-Magic Flute?Mozart Would Approve "Archived6 June 2014 at theWayback Machine(The New York Times,4 July 2005)

- ^"Special report: Hands in their pockets".The Economist.16 August 2001. Archived fromthe originalon 7 September 2018.

- ^Owen, Richard (26 May 2010)."Is it curtains for Italy's opera houses?".The Times.London. Archived fromthe originalon 12 July 2020.Retrieved23 June2010.

- ^Willey, David (27 October 2005)."Italy facing opera funding crisis".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 12 September 2017.Retrieved23 June2010.

- ^"Arts Council England's analysis of its investment in large-scale opera and ballet".Arts Council England.2015. Archived fromthe originalon 23 March 2015.Retrieved5 May2015.

- ^Clark, Nick (15 February 2015)."English National Opera's public funding may be withdrawn"The Independent.Archived29 August 2017 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^Osborne, William (11 March 2004)."Marketplace of Ideas: But First, The Bill A Personal Commentary on American and European Cultural Funding".William Osborne and Abbie Conant.Archivedfrom the original on 25 October 2016.Retrieved21 May2017.

- ^Obituary: Gian Carlo Menotti,The Daily Telegraph,2 February 2007. Accessed 11 December 2008

- ^O'Connor, John J. (1 January 1993)."AToscaperformed on actual location ".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 25 August 2014.Retrieved4 July2010.

- ^Metropolitan OperaArchived5 January 2009 at theWayback Machinehigh-definition live broadcast page

- ^"The Bigger Picture".Thebiggerpicture.us. Archived fromthe originalon 9 November 2010.Retrieved9 November2010.

- ^Emerging PicturesArchived30 June 2008 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Where to See Opera at the Movies",The Wall Street Journal,21–22 June 2008, sidebar p. W10.

- ^Classic FM(26 August 2009)."Download Glyndebourne"Archived23 June 2016 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^Rhinegold Publishing (28 April 2013)."With new pricing and more streaming the Glyndebourne Festival is making its shows available to an ever wider audience"Archived24 June 2016 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^Partii, Heidi (2014)."Supporting Collaboration in Changing Cultural Landscapes",pp. 208–209 in Margaret S Barrett (ed.)Collaborative Creative Thought and Practice in Music.Ashgate Publishing.ISBN1-4724-1584-1

Sources

- Apel, Willi,ed. (1969).Harvard Dictionary of Music(2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.ISBN0-674-37501-7.

- Cooke, Mervyn (2005).The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-78009-8.See also Google Bookspartial preview.

- Parker, Roger,ed. (1994).The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera.Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-816282-0– viaInternet Archive.

- Tyrrell, John."7. Russian, Czech, Polish and Hungarian Opera to 1900". InParker (1994).

Further reading

[edit]- The New Grove Dictionary of Opera,edited byStanley Sadie(1992), 5,448 pages, is the best, and by far the largest, general reference in the English language.ISBN0-333-73432-7,1-56159-228-5

- The Viking Opera Guide,edited byAmanda Holden(1994), 1,328 pages,ISBN0-670-81292-7

- The Oxford Dictionary of Opera,byJohn Warrackand Ewan West (1992), 782 pages,ISBN0-19-869164-5

- Opera, the Rough Guide,by Matthew Boyden et al. (1997), 672 pages,ISBN1-85828-138-5

- Opera: A Concise History,by Leslie Orrey andRodney Milnes,World of Art,Thames & Hudson

- Abbate, Carolyn;Parker, Roger (2012).A History of Opera.New York: W W Norton.ISBN978-0-393-05721-8.

- DiGaetani, John Louis:An Invitation to the Opera,Anchor Books, 1986/91.ISBN0-385-26339-2.

- Dorschel, Andreas, 'The Paradox of Opera',The Cambridge Quarterly30 (2001), no. 4, pp. 283–306.ISSN0008-199X(print).ISSN1471-6836(electronic). Discusses the aesthetics of opera.

- Silke Leopold,"The Idea of National Opera, c. 1800",United and Diversity in European Culture c. 1800,ed.Tim BlanningandHagen Schulze(New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 19–34.