Pastoral

This article has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Thepastoralgenre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle –herdinglivestock around open areas oflandaccording to theseasonsand the changing availability of water andpasture.The target audience is typically anurbanone. Apastoralis a work of thisgenre.A piece of music in the genre is usually referred to as apastorale.

The genre is also known asbucolic,from theGreekβουκολικόν,fromβουκόλος,meaning acowherd.[1][2]

Literature

[edit]Pastoral literature in general

[edit]Pastoral is amodeof literature in which the author employs various techniques to place the complex life into a simple one. Paul Alpers distinguishes pastoral as a mode rather than a genre, and he bases this distinction on the recurring attitude of power; that is to say that pastoral literature holds a humble perspective toward nature. Thus, pastoral as a mode occurs in many types of literature (poetry, drama, etc.) as well as genres (most notably the pastoral elegy).

Terry Gifford, a prominent literary theorist, defines pastoral in three ways in his critical bookPastoral.The first way emphasizes the historical literary perspective of the pastoral in which authors recognize and discuss life in the country and in particular the life of a shepherd.[4]This is summed up byLeo Marxwith the phrase "No shepherd, no pastoral."[4]The second type of the pastoral is literature that "describes the country with an implicit or explicit contrast to the urban".[4]The third type of pastoral depicts the country life with derogative classifications.[4]

Hesiod'sWorks and Dayspresents a 'golden age' when people lived together in harmony with nature. ThisGolden Ageshows that even before theAlexandrian age,ancient Greeks had sentiments of an ideal pastoral life that they had already lost. This is the first example of literature that has pastoral sentiments and may have begun the pastoral tradition. Ovid'sMetamorphosesis much like theWorks and Dayswith the description of ages (golden, silver, bronze, iron, and human) but with more ages to discuss and less emphasis on the gods and their punishments. In this artificially constructed world, nature acts as the main punisher. Another example of this perfect relationship betweenman and natureis evident in the encounter of a shepherd and a goatherd who meet in the pastures inTheocritus' poemIdylls 1.

Traditionally, pastoral refers to the lives of herdsmen in a romanticized, exaggerated, but representative way. Inliterature,the adjective 'pastoral' refers to rural subjects and aspects of life in the countryside amongshepherds,cowherdsand other farm workers that are oftenromanticizedand depicted in a highly unrealistic manner. The pastoral life is usually characterized as being closer to the golden age than the rest of human life. The setting is alocus amoenus,or a beautiful place in nature, sometimes connected with images of theGarden of Eden.[5]An example of the use of the genre is the short poem by the 15th-centuryScottishmakarRobert HenrysonRobene and Makynewhich also contains the conflicted emotions often present in the genre. A more tranquil mood is set byChristopher Marlowe's well known lines from his 1588The Passionate Shepherd to His Love:

Come live with me and be my Love,

And we will all the pleasures prove

That hills and valleys, dale and field,

And all the craggy mountains yield.

There will we sit upon the rocks

And see the shepherds feed their flocks,

By shallow rivers, to whose falls

Melodious birds sing madrigals.

"The Passionate Shepherd to His Love" exhibits the concept of Gifford's second definition of 'pastoral'. The speaker of the poem, who is the titled shepherd, draws on the idealization of urban material pleasures to win over his love rather than resorting to the simplified pleasures of pastoral ideology. This can be seen in the listed items: "lined slippers", "purest gold", "silver dishes", and "ivory table" (lines 13, 15, 16, 21, 23). The speaker takes on a voyeuristic point of view with his love, and they are not directly interacting with the other true shepherds and nature.

Pastoral shepherds and maidens usually haveGreeknames likeCorydonor Philomela, reflecting the origin of the pastoral genre. Pastoral poems are set in beautiful rural landscapes, the literary term for which is "locus amoenus" (Latin for "beautiful place" ), such asArcadia,a rural region ofGreece,mythological home of the godPan,which was portrayed as a sort ofEdenby the poets. The tasks of their employment with sheep and other rustic chores is held in the fantasy to be almost wholly undemanding and is left in the background, leaving the shepherdesses and their swains in a state of almost perfectleisure.This makes them available for embodying perpetualeroticfantasies. The shepherds spend their time chasing pretty girls – or, at least in the Greek and Roman versions, pretty boys as well. The eroticism ofVirgil's secondeclogue,Formosum pastor Corydon ardebat Alexin( "The shepherd Corydon burned with passion for pretty Alexis" ), is entirelyhomosexual.[6]

Pastoral poetry

[edit]

Pastoral literature continued after Hesiod with thepoetryof theHellenisticGreekTheocritus,several of whoseIdyllsare set in the countryside (probably reflecting the landscape of the island ofCoswhere the poet lived) and involve dialogues between herdsmen.[7]Theocritus may have drawn on authentic folk traditions of Sicilian shepherds. He wrote in theDoric dialectbut the metre he chose was thedactylic hexameterassociated with the most prestigious form of Greek poetry,epic.This blend of simplicity and sophistication would play a major part in later pastoral verse. Theocritus was imitated by the Greek poetsBionandMoschus.

The Roman poetVirgiladapted pastoral into Latin with his highly influentialEclogues.Virgil introduces two very important uses of pastoral, the contrast between urban and rural lifestyles and political allegory[8]most notably in Eclogues 1 and 4 respectively. In doing so, Virgil presents a more idealized portrayal of the lives of shepherds while still employing the traditional pastoral conventions of Theocritus. He was the first to set his poems in Arcadia, an idealized location to which much later pastoral literature will refer.

Horace'sEpodes,ii Country Joys has "the dreaming man" Alfius, who dreams of escaping his busy urban life for the peaceful country. But as "the dreaming man" indicates, this is just a dream for Alfius. He is too consumed in his career as ausurerto leave it behind for the country.[9]

LaterSilver Latinpoets who wrote pastoral poetry, modeled principally upon Virgil's Eclogues, includeCalpurnius SiculusandNemesianusand the author(s) of theEinsiedeln Eclogues.

Italian poets revived the pastoral from the 14th century onwards, first in Latin (examples include works byPetrarch,PontanoandMantuan) then in the Italian vernacular (Sannazaro,Boiardo). The fashion for pastoral spread throughout Renaissance Europe.

Leading French pastoral poets includeMarot,a poet of the French court,[10]andPierre de Ronsard,once called the "prince of poets" in his day.[11][12]

The first pastorals in English were theEclogues(c. 1515) ofAlexander Barclay,which were heavily influenced by Mantuan. A landmark in English pastoral poetry wasSpenser’sThe Shepheardes Calender,first published in 1579. Spenser's work consists of twelve eclogues, one for each month of the year, and is written in dialect. It containselegies,fablesand a discussion of the role of poetry in contemporary England. Spenser and his friends appear under various pseudonyms (Spenser himself is "Colin Clout" ). Spenser's example was imitated by such poets asMichael Drayton(Idea, The Shepherd's Garland) andWilliam Browne(Britannia's Pastorals). During this period of England's history, many authors explored "anti-pastoral" themes.[14]Two examples of this,Sir Philip Sidney's “The Twenty-Third Psalm” and “The Nightingale”, focus on the world in a very anti-pastoral view. In “The Twenty-Third Psalm,” Nature is portrayed as something we need to be protected from, and in “The Nightingale,” the woe ofPhilomelais compared to the speaker's own pain. Sidney also wroteArcadia,which is filled with pastoral descriptions of the landscape. "The Nymph's Reply to the Shepherd"(1600) bySir Walter Raleighalso comments on the anti-pastoral as the nymph responds realistically to the idealizing shepherd ofThe Passionate Shepherd to His Loveby embracing and explaining the true course of nature and its incompatibility with the love that the Shepherd yearns for with the nymph. Terry Gifford defined the anti-pastoral in his 2012 essay "Pastoral, Anti-Pastoral and Post-Pastoral as Reading Strategies" as an often explicit correction of pastoral, emphasizing "realism" over romance, highlighting problematic elements (showing tensions, disorder and inequalities), challenging literary constructs as false distortions and demythologizing mythical locations such asArcadiaandShangri-La.[15]

In the 17th century came theCountry house poem.Included in this genre isEmilia Lanier'sThe Description of Cooke-hamin 1611, in which a woman is described in terms of her relationship to her estate and how it mourns for her when she leaves it. In 1616,Ben JonsonwroteTo Penshurst,a poem in which he addresses the estate owned by the Sidney family and tells of its beauty. The basis of the poem is a harmonious and joyous elation of the memories that Jonson had at the manor. It is beautifully written with iambic pentameter, a style that Jonson eloquently uses to describe the culture of Penshurst. It includes Pan and Bacchus as notable company of the manor. Pan, Greek god of the Pastoral world, half man and half goat, was connected with both hunting and shepherds;Bacchuswas the god of wine, intoxication and ritual madness. This reference to Pan and Bacchus in a pastoral view demonstrates how prestigious Penshurst was, to be worthy in the company with gods.

"A Country Life", another 17th-century work byKatherine Philips,was also a country house poem. Philips focuses on the joys of the countryside and looks upon the lifestyle that accompanies it as being "the first and happiest life, when man enjoyed himself." She writes about maintaining this lifestyle by living detached from material things, and by not over-concerning herself with the world around her.Andrew Marvell's "Upon Appleton House"was written when Marvell was working as a tutor for Lord Fairfax's daughter Mary, in 1651. The poem is very rich with metaphors that relate to religion, politics and history. Similar to Jonson's" To Penshurst ", Marvell's poem is describing a pastoral estate. It moves through the house itself, its history, the gardens, the meadows and other grounds, the woods, the river, his Pupil Mary, and the future. Marvell used nature as a thread to weave together a poem centered around man. We once again see nature fully providing for man. Marvell also continuously compares nature to art and seems to point out that art can never accomplish on purpose what nature can achieve accidentally or spontaneously.

Robert Herrick'sThe Hock-cart, or Harvest Homewas also written in the 17th century. In this pastoral work, he paints the reader a colorful picture of the benefits reaped from hard work. This is an atypical interpretation of the pastoral, given that there is a celebration of labor involved as opposed to central figures living in leisure and nature just taking its course independently. This poem was mentioned inRaymond Williams',The Country and the City.This acknowledgment of Herrick's work is appropriate, as both Williams and Herrick accentuate the importance of labor in the pastoral lifestyle.

Thepastoral elegyis a subgenre that uses pastoral elements to lament a death or loss. The most famous pastoral elegy in English isJohn Milton's "Lycidas"(1637), written on the death of Edward King, a fellow student at Cambridge University. Milton used the form both to explore his vocation as a writer and to attack what he saw as the abuses of the Church. Also included isThomas Gray's, "Elegy In a Country Churchyard" (1750).

The formal English pastoral continued to flourish during the 18th century, eventually dying out at the end. One notable example of an 18th-century work isAlexander Pope'sPastorals(1709). In this work Pope imitatesEdmund Spenser'sShepheardes Calendar,while utilizing classical names and allusions aligning him withVirgil.In 1717, Pope'sDiscourse on Pastoral Poetrywas published as a preface toPastorals.In this work Pope sets standards for pastoral literature and critiques many popular poets, one of whom is Spenser, along with his contemporary opponentAmbrose Philips.During this time period Ambrose Philips, who is often overlooked because of Pope, modeled his poetry after the native English form of Pastoral, employing it as a medium to express the true nature and longing of Man. He strove to write in this fashion to conform to what he thought was the original intent of Pastoral literature. As such, he centered his themes around the simplistic life of the Shepherd, and, personified the relationship that humans once had with nature.John Gay,who came a little later was criticized for his poem's artificiality byDoctor Johnsonand attacked for their lack of realism byGeorge Crabbe,who attempted to give a true picture of rural life in his poemThe Village.

In 1590, Edmund Spenser also composed the famous pastoral epicThe Faerie Queene,in which he employs the pastoral mode to accentuate the charm, lushness, and splendor of the poem's (super)natural world. Spenser alludes to the pastoral continuously throughout the work and also uses it to create allegory in his poem, with the characters as well as with the environment, both of which are meant to have symbolic meaning in the real world. It is of six 'books' only, though Spenser intended to write twelve. He wrote the poem primarily to honorQueen Elizabeth.William Cowperaddressed the artificiality of the fast-paced city life in his poemsRetirement(1782) andThe Winter Nosegay(1782). Pastoral nevertheless survived as a mood rather than a genre, as can be seen from such works asMatthew Arnold'sThyrsis(1867), a lament on the death of his fellow poetArthur Hugh Clough.Robert Burnscan be read as a Pastoral poet for his nostalgic portrayals of rural Scotland and simple farm life inTo A MouseandThe Cotter's Saturday Night.Burns explicitly addresses the Pastoral form in hisPoem on Pastoral Poetry.In this he champions his fellow ScotAllan Ramseyas the best Pastoral poet sinceTheocritus.

Another subgenre is the Edenic Pastoral, which alludes to the perfect relationship between God, man, and nature in theGarden of Eden.It typically includes biblical symbols and imagery. In 1645 John Milton wroteL'Allegro,which translates as the happy person. It is a celebration ofMirthpersonified, who is the child of love and revelry. It was originally composed to be a companion poem to,Il Penseroso,which celebrates a life of melancholy and solitude. Milton's,On the Morning of Christ's Nativity(1629) blends Christian and pastoral imagery.

Pastoral epic

[edit]Milton is perhaps best known for his epicParadise Lost,one of the few Pastoral epics ever written. A notable part of Paradise Lost is book IV where he chronicles Satan's trespass into paradise. Milton's iconic descriptions of the garden are shadowed by the fact that we see it from Satan's perspective and are thus led to commiserate with him. Milton elegantly works through a presentation ofAdam and Eve’s pastorally idyllic, eternally fertile living conditions and focuses upon their stewardship of the garden. He gives much focus to the fruit bearing trees and Adam and Eve's care of them, sculpting an image of pastoral harmony. However, Milton in turn continually comes back toSatan,constructing him as a character the audience can easily identify with and perhaps even like. Milton creates Satan as character meant to destabilize the audience’s understanding of themselves and the world around them. Through this mode, Milton is able to create a working dialogue between the text and his audience about the ‘truths’ they hold for themselves.

Pastoral romances

[edit]Italian writers invented a new genre, the pastoral romance, which mixed pastoral poems with a fictional narrative in prose. Although there was no classical precedent for the form, it drew some inspiration from ancient Greek novels set in the countryside, such asDaphnis and Chloe.The most influential Italian example of the form wasSannazzaro'sArcadia(1504). The vogue for the pastoral romance spread throughout Europe producing such notable works asBernardim Ribeiro"Menina e Moça" (1554) in Portuguese,[16]Montemayor'sDiana(1559) in Spain,Sir Philip Sidney'sArcadia(1590) in England, andHonoré d'Urfé'sAstrée(1607–27) in France.

Pastoral plays

[edit]| Reformation-era literature |

|---|

Pastoral drama also emerged in Renaissance Italy. Again, there was little Classical precedent, with the possible exception of Greeksatyr plays.Poliziano'sOrfeo(1480) shows the beginnings of the new form, but it reached its zenith in the late 16th century withTasso'sAminta(1573),Isabella Andreini'sMirtilla(1588), andGuarini'sIl pastor fido(1590).John Lyly'sEndimion(1579) brought the Italian-style pastoral play to England.John Fletcher'sThe Faithful Shepherdess,Ben Jonson'sThe Sad Shepherdand Sidney'sThe Lady of Mayare later examples. Some ofShakespeare's plays contain pastoral elements, most notablyAs You Like It(whose plot was derived fromThomas Lodge's pastoral romanceRosalynde) andThe Winter's Tale,of which Act 4 Scene 4 is a lengthy pastoral digression.

The forest inAs You Like Itcan be seen as a place of pastoral idealization, where life is simpler and purer, and its inhabitants live more closely to each other, nature and God than their urban counterparts. However, Shakespeare plays with the bounds of pastoral idealization. Throughout the play, Shakespeare employs various characters to illustratepastoralism.His protagonistsRosalindandOrlandometaphorically depict the importance of the coexistence of realism and idealism, or urban and rural life. While Orlando is absorbed in the ideal, Rosalind serves as a mediator, bringing Orlando back down to reality and embracing the simplicity of pastoral love. She is the only character throughout the play who embraces and appreciates both the real and idealized life and manages to make the two ideas coexist. Therefore, Shakespeare explores city and country life as being appreciated through the coexistence of the two.

Pastoral science fiction

[edit]

Pastoral science fictionis a subgenre ofscience fictionwhich uses bucolic,ruralsettings, like other forms of pastoral literature. Since it is a subgenre of science fiction, authors may set stories either onEarthor another habitableplanetor moon, sometimes including aterraformedplanet or moon. Unlike most genres of science fiction, pastoral science fiction works downplay the role of futuristic technologies. In the 1950s and 1960s,Clifford Simakwrote stories about rural people who have contact withextraterrestrial beingswho hide their alien identity.[17]

Pastoral science fiction stories typically show a reverence for the land, its life-giving food harvests, the cycle of the seasons, and the role of the community. While fertile agrarian environments on Earth or Earth-like planets are common settings, some works may be set in ocean or desert planets or habitable moons. The rural dwellers, such as farmers and small-townspeople, are depicted sympathetically, albeit with the tendency to portray them asconservativeand suspicious of change. The simple, peaceful rural life is often contrasted with the negative aspects of noisy, dirty, fast-paced cities. Some works take aLudditetone, criticizing mechanization andindustrializationand showing the ills ofurbanizationand over-reliance on advanced technologies.

Post-pastoral, urban pastoral and other variants

[edit]In 1994, British literature professorTerry Giffordproposed the concept of a "post-pastoral" subgenre. By appending the prefix "post-", Gifford does not intend this to refer to “after” but rather to the sense of “reaching beyond” the contraints of the pastoral genre, but while continuing the core conceptual elements that have defined the pastoral tradition. Gifford states that the post-pastoral is "best used to describe works that successfully suggest a collapse of the human/nature divide whilst being aware of the problematics involved", noting that it is "more about connection than the disconnections essential to the pastoral".[18]He gives examples of post-pastoral works, includingCormac McCarthy’sThe Road(2006),Margaret Atwood’sThe Year of the Flood(2009) andMaggie Gee’sThe Ice People(1999), and he points out that these works "raise questions of ethics, sustenance and sustainability that might exemplify [Leo]Marx’svision of the pastoral needing to find new forms in the face of new conditions ".[18]

Gifford states that British eco-critics such as Greg Garrard have used the "post-pastoral" concept, as well as two other variants: "gay pastoral", the seemingly contradictory "urban pastoral"[18]and "radical pastoral".[19]Gifford lists further examples of pastoral variants, which he calls "prefix-pastoral[s]": "postmodernpastoral,...hard pastoral, soft pastoral, Buell’s revolutionarylesbianfeminist pastoral, black pastoral, ghetto pastoral, frontier pastoral, militarized pastoral, domestic pastoral and, most recently, a specifically ‘Irish pastoral' ".[18]

In 2014,The Cambridge Companion to the City in Literaturehad a chapter on the urban pastoral subgenre.[20]Charles Siebert'sWickerby: An Urban Pastoraldescribes a man who splits his time between a gritty Brooklyn apartment, where the night is filled with the sounds of pigeons, starlings, and youth gangs shouting, and driving to rural Quebec tosquatin an abandoned, tumbledown cabin in rural Quebec.[21]

Pastoral music

[edit]Theocritus'sIdyllsinclude strophic songs and musical laments, and, as inHomer,his shepherds often play thesyrinx,or pan flute, which is considered a quintessentially pastoral instrument. Virgil'sEclogueswere performed as sung mime in the 1st century, and there is evidence of the pastoral song as a legitimate genre of classical times.

The pastoral genre was a significant influence in the development ofopera.After settings of pastoral poetry in thepastourellegenre by thetroubadours,Italian poets and composers became increasingly drawn to the pastoral. Musical settings of pastoral poetry became increasingly common in first polyphonic and thenmonodicmadrigals:these later led to thecantataand theserenata,in which pastoral themes remained on a consistent basis. Partial musical settings ofGiovanni Battista Guarini'sIl pastor fidowere highly popular: the texts of over 500 madrigals were taken from this one play alone.Tasso'sAmintawas also a favourite. Asoperadeveloped, the dramatic pastoral came to the fore with such works asJacopo Peri'sDafneand, most notably,Monteverdi'sL'Orfeo.Pastoral opera remained popular throughout the 17th-century, and not just in Italy, as is shown by the French genre ofpastorale héroïque,EnglishmanHenry Lawes's music forMilton'sComus(not to mentionJohn Blow'sVenus and Adonis), and Spanishzarzuela.At the same time, Italian and German composers developed a genre of vocal and instrumental pastorals, distinguished by certain stylistic features, associated with Christmas Eve.

The pastoral, and parodies of the pastoral, continued to play an important role in musical history throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.John Gaymay have satirized the pastoral inThe Beggar's Opera,but also wrote an entirely sincere libretto forHandel'sAcis and Galatea.[22]Rousseau'sLe Devin du villagedraws on pastoral roots, andMetastasio's librettoIl re pastorewas set over 30 times, most famously byMozart.Rameauwas an outstanding exponent of French pastoral opera.[23]Beethovenalso wrote his famousPastoral Symphony,avoiding his usual musical dynamism in favour of relatively slow rhythms. More concerned with psychology than description, he labelled the work "more the expression of feeling than [realistic] painting". The pastoral also appeared as a feature ofgrand opera,most particularly in Meyerbeer's operas: often composers would develop a pastoral-themed "oasis", usually in the centre of their work. Notable examples include the shepherd's "alte Weise" fromWagner'sTristan und Isolde,or the pastoral ballet occupying the middle ofTchaikovsky'sThe Queen of Spades.The 20th-century continued to bring new pastoral interpretations, particularly in ballet, such as Ravel'sDaphis and Chloe,Nijinsky's use of Debussy'sPrélude à l'après-midi d'un faune,andStravinsky'sLe sacre du printempsandLes Noces.[24]

ThePastoraleis a form ofItalian folk songstill played in the regions of Southern Italy where thezampognacontinues to thrive. They generally sound like a slowed down version of atarantella,as they encompass many of the same melodic phrases. The pastorale on the zampogna can be played by a solo zampogna player, or in some regions can be accompanied by the piffero (also commonly called aciaramella,'pipita', orbifora), which is a primitive key-less double reedoboetype instrument.

Pastoral art

[edit]Idealised pastoral landscapes appear in Hellenistic and Roman wall paintings. Interest in the pastoral as a subject for art revived in Renaissance Italy, partly inspired by the descriptions of picturesJacopo Sannazaroincluded in hisArcadia.ThePastoral Concertin theLouvreattributed toGiorgioneorTitianis perhaps the most famous painting in this style. Later, French artists were also attracted to the pastoral, notablyClaude,Poussin(e.g.,Et in Arcadia ego) andWatteau(in hisFêtes galantes).[25]TheFête champêtre,with scenes of country people dancing was a popular subject in Flemish painting.Thomas Colehas a series of paintings titledThe Course of Empire,and the second of these paintings (shown on the right) depicts the perfect pastoral setting.

-

Nicolas PoussinArcadian Shepherds,1627,Chatsworth House

-

Thomas Cole,The Course of Empire,The ArcadiaorPastoral State,1834

Religious usage

[edit]In Christianity

[edit]

Pastoral imagery and symbolism feature heavily in Christianity and the Bible.[27]Jesuscalls himself the "Good Shepherd" inJohn 10:11,contrasting his role as theLamb of God.[28]

Many Christian denominations use the title "Pastor",[29]a word rooted in theBiblicalmetaphor of shepherding. (Pastorin Latin means "shepherd" ). TheHebrew Bible(or Old Testament) uses theHebrewwordרעה(roʿeh), which is used as a noun as in "shepherd", and as a verb as in "to tend a flock."[30]It occurs 173 times in 144 Old Testament verses and relates to the literal feeding of sheep, as inGenesis29:7. InJeremiah23:4, both meanings are used (ro'imis used for "shepherds" andyir'umfor "shall feed them" ), "And I will set up shepherds over them which shall feed them: and they shall fear no more, nor be dismayed, neither shall they be lacking, saith the LORD." (KJV).

A pastoral economic system had great cultural significance for the Jewish people from earliest recorded times:Abrahamherded flocks. Throughout the biblical accounts of theChildren of Israel,a pastoral lifestyle in the harsh hinterland of the Levant related to the ideal of a society obedient toYahweh,in contrast to the corruption andidolatryencountered in the "fleshpots of Egypt" (Exodus 16:3), in the lushCanaanitelowlands "flowing with milk and honey" (Exodus 3:8), or inBabylon,the "great city" of Israelite exile.David,a righteous shepherd-boy associated with the arid hill-country, contrasts withGoliathandSaul,representatives of luxurious urban élites. Thus New Testament imagery of shepherds and their sheep builds on established cultural and economic distinctions familiar, directly or indirectly, to the Jewish world at the time of the origins of Christianity in the first century CE.

Apastoral letter,often called simply a pastoral, is an open letter addressed by a bishop to the clergy or laity of a diocese or to both, containing general admonition, instruction or consolation, or directions for behavior in particular circumstances. In mostepiscopalchurch bodies, clerics are often required to read out pastoral letters of superior bishops to their congregations.

Thepastoral epistlesare a group of three books of thecanonicalNew Testament:theFirst Epistle to Timothy(1 Timothy) theSecond Epistle to Timothy(2 Timothy), and theEpistle to Titus.They are presented as letters fromPaul the ApostletoTimothyand toTitus.They are generally discussed as a group (sometimes with the addition of theEpistle to Philemon) and are given the title"pastoral"because they are addressed to individuals with pastoral oversight of churches and discuss issues of Christian living, doctrine andleadership.

Pastoral theory

[edit]In the past four hundred years, a range of writers have worked on theorizing the nature of pastoral. These includeFriedrich Schiller,[31]George Puttenham,[32]William Empson,[33]Frank Kermode,[34]Raymond Williams,[35]Renato Poggioli,[36]Annabel Patterson,[37]Paul Alpers,[38]and Ken Hiltner.[39]George Puttenhamwas one of the first Pastoral theorists. He did not see the form as merely a recording of a prior rustic way of life but a guise for political discourse, which other forms had previously neglected. The Pastoral, he writes, has a didactic duty to “contain and enforme morall discipline for the amendment of mans behaviour”.[32]

Friedrich Schillerlinked the Pastoral to childhood and a childlike simplicity. For Schiller, we perceive in nature an “image of our infancy irrevocably past”.[40]Sir William Empsonspoke of the ideal of Pastoral as being embedded in varying degrees of ambivalence, and yet, for all the apparent dichotomies, and contradicting elements found within it, he felt there was a unified harmony within it. He refers to the pastoral process as 'putting the complex into the simple.' Empson argues that "... good proletarian art is usually Covert Pastoral", and uses Soviet Russia's propaganda about the working class as evidence. Empson also emphasizes the importance of the double plot as a tool for writers to discuss a controversial topic without repercussions.

Raymond Williamsargues that the foundation of the pastoral lies in the idea that the city is a highly urban, industrialized center that has removed us from the peaceful life we once had in the countryside. However, he states that this is really a "myth functioning as a memory" that literature has created in its representations of the past. As a result, when society evolves and looks back to these representations, it considers its own present as the decline of the simple life of the past. He then discusses how the city's relationship with the country affected the economic and social aspects of the countryside. As the economy became a bigger part of society, many country newcomers quickly realized the potential and monetary value that lay in the untouched land. Furthermore, this new system encouraged a social stratification in the countryside. With the implementation of paper money came a hierarchy in the working system, as well as the "inheritance of titles and making of family names".

Poggioliwas concerned with how death reconciled itself with the pastoral, and thus came up with a loose categorization of death in the pastoral as 'funeral elegy', the most important tropes of which he cites as religion (embodied by Pan); friendship; allegory;and poetic and musical calling. He concedes though that such a categorization is open to much misinterpretation. As well, Poggioli focused on the idea that Pastoral was a nostalgic and childish way of seeing the world. InThe Oaten Flue,he claims that the shepherd was looked up to was because they were “an ideal kind of leisure class."

Frank Kermodediscusses the pastoral within the historical context of the English Renaissance. His first condition of pastoral poetry is that it is an urban product. Kermode establishes that the pastoral is derived as an opposition between two modes of living, in the country and in the city. London was becoming a modern metropolis before the eyes of its citizens. The result of this large-scaleurban sprawlleft the people with a sense of nostalgia for their country way of living. His next argument focuses on the artificiality of poetry, drawing upon fellow theorist, Puttenham.

Kermode elaborates on this and says, "the cultivated, in their artificial way, reflect upon and describe, for their own ends, the natural life". Kermode wants us to understand that the recreation or reproduction of the natural is in itself artificial. Kermode elaborates on this in terms of imitation, describing it as "one of the fundamental laws of literary history" because it "gives literary history a meaning in terms of itself, and provides the channels of literary tradition". Kermode goes on to explain about the works of Virgil and Theocritus as progenitors of the pastoral. Later poets would draw on these earlier forms of pastoral, elaborating on them to fit their own social context. As the pastoral was becoming more modern, it shifted into the form of Pastourelle. This is the first time that the pastoral really deals with the subject of love.

Annabel Pattersonemphasizes many important ideas in her work, Pastoral and Ideology. One of these is that the pastoral mode, especially in the later 18th century, was interpreted in vastly different ways by different groups of people. As a result, distinctive illustrations emerged from these groups which were all variations of the understanding of Virgil's Eclogues. Patterson explains that Servius' Commentary is essential to understanding the reception of Virgil's Eclogues. The commentary discusses how poets used analogy in their writings to indirectly express the corruption within the church and government to the public. When speaking of post-Romanticism, it is imperative to take into consideration the influence and effect ofRobert Froston pastoral ideology. His poem,Build Soilis a critique of war and also a suggestion that pastoral, as a literary mode, should not place emphasis on social and political issues, but should rather, as Patterson says, "turn in upon itself, and replace reformist instincts with personal growth and regeneration".William Wordsworthwas a highly respected poet in the 1800s and his poem,Prelude,published in 1805, was an excellent example of what a dream of a new golden age might materialize as or look like.

Paul Alpers, in his 1996 book,What is Pastoral?,describes the recurring plot of pastoral literature as the lives of shepherds. With William Empson's notion of placing the complex into the simple, Alpers thus critically defines pastoral as a means of allegory. Alpers also classifies pastoral as a mode of literature, as opposed to a genre, and he defines the attitude of pastoral works maintaining a humble relationship with nature. Alpers also defines pastoral convention as the act of bringing together, and authors use this to discuss loss. He says the speakers in pastoral works are simple herdsmen dramatized in pastoral encounters.

However, authors like Herrick changed the herdsmen to nymphs, maidens, and flowers. Thus, achieving a mode of simplicity but also giving objects voice. This is done by personifying objects like flowers. Moreover, authors that do this in their works are giving importance to the unimportant. Alpers talks about pastoral lyrics and love poems in particular. He says "a lyric allows its speaker to slip in and out of pastoral guise and reveal directly the sophistication which prompted him to assume it in the first place″. In other words, he claims pastorals lyrics have both pastoral and not pastoral characteristics, perhaps like in the comparisons between urban and rural, but they always give importance to and enhance on the pastoral. Alpers talks about love poems and how they can be turned into pastoral poems simply by changing words like lover to shepherd. And he mentions Shakespeare as one of the authors who did this in his works. Furthermore, Alpers says the pastoral is not only about praise for the rural and the country side. For instance, Sidney dispraises the country life inThe Garden.Pastoral can also include the urban, the court, and the social like inL’Allegro.

Alpers says that pastoral narration contradicts “normal” narrative motives and that there is a double aspect of pastoral narration: heroic poetry and worldly realities with narrative motives and conventions. And in respect to pastoral novels, Alpers says pastoral novels have different definitions and examples depending on the reader. Also, the pastoral novel differs from Theocritus and Virgil's works. He says there are pastoral novels of the country life, of the longing for the simple, and with nature as the protagonist. And says the literary category of pastoral novels is realistic and post-realistic fiction with a rural theme or subject based on traditional pastoral.

InWhat Else Is Pastoral?,Ken Hiltner argues that Renaissance pastoral poetry is more often a form ofnature writingthan critics like Paul Alpers and Annabel Patterson give it credit for. He explains that even though there is a general lack of lavish description in Renaissance pastoral, this is because they were beginning to use gestural strategies, and artists begin to develop an environmental consciousness as nature around them becomes endangered. Another argument presented in the book is that our current environmental crisis clearly has its roots in the Renaissance. To do this we are shown examples in Renaissance pastoral poetry that show a keen awareness of the urban sprawl of London contrasted to the countryside and historical records showing that many at the time were aware of the issue of urban growth and attempted to stop it.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^βουκολικόν.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;A Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project.βουκόλος.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;An Intermediate Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project.

- ^Harper, Douglas."bucolic".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^King, Charles William (1885).Handbook of Engraved Gems(2nd ed.). London: George Bell and Sons. p. 215.

- ^abcdGifford, Terry (1999).Pastoral.The New Critical Idiom. London; New York: Routledge. pp.1–12.ISBN0415147328.

- ^Bridget Ann Henish,The Medieval Calendar Year,p. 96,ISBN0-271-01904-2

- ^Richter, Simon (2008).Goethe Yearbook.Suffolk: Camden House. pp. 81–82.ISBN9781571133144.

- ^Introduction (p. 14) to Virgil:The Ecloguestrans. Guy Lee (Penguin Classics)

- ^Article on "Bucolic poetry" inThe Oxford Companion to Classical Literature(1989)

- ^Horace'sDelights of the CountryEpode iiRetrieved October 14, 2011

- ^Patterson, Annabel (1986)."Re-opening the Green Gabinet: Glément Marot and Edmund Spenser".English Literary Renaissance.16(1): 44–70.doi:10.1111/j.1475-6757.1986.tb00897.x.ISSN0013-8312.JSTOR43447343.S2CID145192804.

- ^O'Donoghue, Samuel (2015)."Pastoral Paratexts: The Political and the Lyrical in Garcilaso de la Vega and Pierre de Ronsard".The Modern Language Review.110(1): 1–27.doi:10.5699/modelangrevi.110.1.0001.ISSN0026-7937.JSTOR10.5699/modelangrevi.110.1.0001.

- ^Wells, B. W. (1893)."Pierre De Ronsard, 'Prince of Poets'".The Sewanee Review.1(2): 161–180.ISSN0037-3052.JSTOR27527740.

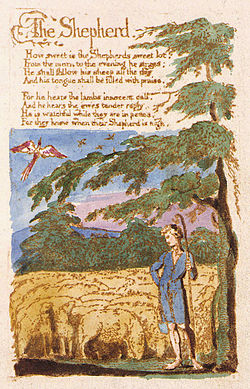

- ^Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.)."Songs of Innocence, copy B, object 4 (Bentley 5, Erdman 5, Keynes 5) 'The Shepherd'".William Blake Archive.RetrievedJanuary 17,2014.

- ^Gifford, Terry (2013), Westling, Louise (ed.),"Pastoral, Anti-Pastoral, and Post-Pastoral",The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Environment,Cambridge Companions to Literature, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 17–30,ISBN978-1-107-62896-0,retrieved2020-10-15

- ^Gifford, T. and Slovic, S. (Ed.) (2012) “Pastoral, Anti-Pastoral and Post-Pastoral as Reading Strategies”, Critical Insights: Nature and Environment, pp. 42–61, Ipswich: Salam Press.

- ^Warner, Charles Dudley (2008).A Library of the World's Best Literature – Ancient and Modern – Vol. XLIII.Cosimo, Inc. p. 456.ISBN978-1-60520-251-8.

- ^Jordison, Sam (2009-03-03)."Clifford D Simak: sci-fi in the countryside".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved2023-11-15.

- ^abcdGifford, Terry.The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Environment,p. 17. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139342728.003.Cambridge University Press, 2013

- ^Garrard, Greg. "Radical Pastoral?"Studies in Romanticism. Vol. 35, No. 3, Green Romanticism (Fall, 1996), pp. 449–465 (17 pages). The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^McNamara, K., & Gray, T. (2014). Some Versions of Urban Pastoral. In K. McNamara (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the City in Literature (Cambridge Companions to Literature, pp. 245–260). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.doi:10.1017/CCO9781139235617.020

- ^Seibert, Charles.Wickerby: An Urban Pastoral.Crown Publishers, Inc., 1998

- ^Saylor, Eric.English Pastoral Music: From Arcadia to Utopia, 1900–1955(2017), Chapter 2

- ^SeeCuthbert Girdlestone,Jean-Philippe Rameau: His Life and Work,particularly pp. 377 ff.

- ^General reference for this section:Geoffrey Chewand Owen Jander (2001).Pastoral.Grove Music Online.ISBN978-1561592630.

- ^Article on "Pastoral" inThe Oxford Companion to Art(ed. H. Osborne)

- ^From the Louvre Museum Official WebsiteArchived2009-06-28 at theWayback MachineIt is often called theFête Champêtre(meaning "Picnic" ) in older works.

- ^""THE LITERARY STUDY OF THE BIBLE AN ACCOUNT OF THE LEADING FORMS OF LITERATURE REPRESENTED IN THE SACRED WRITINGS INTENDED FOR ENGLISH READERS" By RICHARD G. MOULTON "(PDF).

- ^"AHA".Christ as the Good Shepherd.2020-07-01.Retrieved2021-09-15.

- ^"pastor | Definition of pastor in English by Oxford Dictionaries".Oxford Dictionary English.Archived fromthe originalon September 26, 2016.Retrieved2018-06-10.

- ^"Genesis 1:1 (KJV)".Blue Letter Bible.Retrieved2018-06-10.

- ^Friedrich Schiller,On Naive and Sentimental Poetry(1795).

- ^abGeorge Puttenham,Arte of English Poesie(1589).

- ^William Empson,Some Versions of Pastoral.(1935).

- ^Frank Kermode,English Pastoral Poetry: From the Beginnings to Marvell.(1952).

- ^Raymond Williams,The Country and the City.Oxford U P, 1973.

- ^Renato Poggioli,The Oaten Flute: Essays on Pastoral Poetry and the Pastoral Ideal.Harvard U P, 1975.

- ^Annabel Patterson.Pastoral and ideology: Virgil to Valéry.U of California P, 1987.

- ^Paul Alpers,What is Pastoral?U of Chicago P, 1996.

- ^Ken Hiltner,What Else is Pastoral?: Renaissance Literature and the Environment.Cornell U P, 2011.

- ^Schiller, Friedrich."On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry".The Schiller Institute.Translated by William F. Wertz, Jr.RetrievedMarch 14,2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Gosse, Edmund William(1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 896–898.

- Holloway, Anne (2017).The Potency of Pastoral in the Hispanic Baroque.Woodbridge: Támesis.

- John Dixon Hunt (ed),The Pastoral Landscape,1992, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Studies in the History of Art 36,ISBN0-89468-181-8

External links

[edit]- TwoIdyllsby Theocritus (English)

- TheEcloguesof Virgil

- The complete works ofChristopher Marlowe

- Shepheardes CalendarbyEdmund Spenser

- La Castità Conquistata: The Function of the Satyr in Pastoral Drama,by Meredith Kennedy Ray (University of Chicago)

- 'The Pastoral Concert' at the Louvre site

- Pastoral Literature,BBC Radio 4 discussion with Helen Cooper, Laurence Lerner & Julie Sanders (In Our Time,July 6, 2006)

![Giorgione or Titian, Pastoral Concert, c. 1509, Louvre.[26]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Fiesta_campestre.jpg/200px-Fiesta_campestre.jpg)