Patronage in ancient Rome

Patronage(clientela) was the distinctive relationship inancient Roman societybetween thepatronus('patron') and theircliens('client'). Apart from the patron-client relationship between individuals, there were also client kingdoms and tribes, whose rulers were in a subordinate relationship to the Roman state.

The relationship was hierarchical, but obligations were mutual. The patron was the protector, sponsor, and benefactor of the client; the technical term for this protection waspatrocinium.[1]Although typically the client was of inferior social class,[2]a patron and client might even hold the same social rank, but the former would possess greater wealth, power, or prestige that enabled him to help or do favors for the client.

From the emperor at the top to the commoner at the bottom, the bonds between these groups found formal expression in legal definition of patrons' responsibilities to clients.[3]Patronage relationships were not exclusively between two people and also existed between ageneralandhis soldiers,afounder and colonists,and a conqueror and adependent foreign community.[4]

Nature ofclientela

[edit]Benefits a client may be granted includelegal representationin court, loans of money, influencing business deals ormarriages,and supporting a client's candidacy forpolitical officeor apriesthood.Arranging marriages for their daughters, clients were often able to secure new patrons and extend their influence in the political arena.[5]In return for these services, the clients were expected to offer their services to their patron as needed. A client's service to the patron included accompanying the patron in Rome or when he went to war,ransominghim if he was captured, and supporting him during political campaigns.[6][7][8]

Requests were usually made byclientelaat a daily morning reception at the patron's home, known as thesalutatio.The patron would receive his clients at dawn in theatriumandtablinum,after which the clients would escort the patron to theforum.[9]The number of clients who accompanied their patron was seen as a symbol of the patron's prestige.[6]The client was regarded as a minor member of their patron'sgens,entitled to assist in itssacra gentilicia,and bound to contribute to the cost of them. The client was subject to the jurisdiction and discipline of the gens, and was entitled to burial in its commonsepulchre.[10]

One of the major spheres of activity within patron–client relations was thelaw courts,butclientelawas not itself a legal contract, although it was supported by law fromearliest Roman times.[11]The pressures to uphold one's obligations were primarily moral, founded onancestral custom,and on qualities ofgood faithon the part of the patron andloyaltyon the part of the client.[12]The patronage relationship was not a discrete one, but a network, since apatronusmight himself be obligated to someone of higher status or greater power. Acliensmight have more than one patron, whose interests could come into conflict. While theRomanfamilia('family', but more broadly the "household" ) was the building block of society, interlocking networks of patronage created highly complex social bonds.[13]

Reciprocity ethics played a major role in the patron client system. Favors given from patron to client and client to patron do not cancel the other, instead the giving of favors and counter favors was symbolic of the personal relationship between patron and client. As a consequence, the act of returning a favor was done more out of a sense of gratuity and less so because a favor needed to be returned.[14]

The regulation of the patronage relationship was believed by the Greek historiansDionysiusandPlutarchto be one of the early concerns ofRomulus.Hence, it was dated to the veryfounding of Rome.[10]In the earliest periods, patricians would have served as patrons. Bothpatricius,'patrician', andpatronusare related to the Latin wordpater,'father', in this sense symbolically, indicating thepatriarchalnature of Roman society. Although other societies have similar systems, thepatronus–cliensrelationship was "peculiarly congenial" to Roman politics and the sense offamiliain theRoman Republic.[15]An important person demonstrated their prestige ordignitasby the number of clients they had.[16]

Patronusandlibertus

[edit]When aslavewasmanumitted,the former owner became their patron. Thefreedman(libertus)had social obligations to their patron, which might involve campaigning on their behalf if the patron ran for election, doing requested jobs or errands, or continuing asexual relationship that began in servitude.In return, the patron was expected to ensure a certain degree of material security for their client. Allowing one's clients to becomedestituteor entangled in unjust legal proceedings would reflect poorly on the patron and diminish their prestige.[citation needed]

Changing nature of patronage

[edit]

The complex patronage relationships changed with the social pressures during thelate Republic,when terms such aspatronus,cliensandpatrociniumare used in a more restricted sense thanamicitia,'friendship', including political friendships and alliances, orhospitium,reciprocal "guest–host" bonds between families.[17]It can be difficult to distinguishpatrociniumorclientela,amicitia,andhospitium,since their benefits and obligations overlap.[18]Traditionalclientelabegan to lose its importance as a social institution during the 2nd century BC;[19]Fergus Millardoubts that it was the dominant force inRoman electionsthat it has often been seen as.[20]

Throughout the evolution from republic to empire we see the most diversity between patrons. Patrons from all positions of power sought to build their power through the control of clients and resources. More and more patronage extended over entire communities whether on the basis of political decree, benefaction by an individual who becomes the communities' patron, or by the community formally adopting a patron.[21]

Both sides had expectations of one another. The community expected protection from outside forces, while the patron expected a loyal following for things such as political campaigning and manpower should the need arise. The extent of a person's client relationships was often taken into account when looking for an expression of their potential political power.[21]

Patronage in the late empire differed from patronage in the republic. Patrons protected individual clients from the tax collector and other public obligations. In return, clients gave them money or services. Some clients even surrendered ownership of their land to their patron. The emperors were unable to prevent this type of patronage effectively.[22]The significance ofclientelachanged along with the social order duringlate antiquity.By the 10th century,clientelameant a contingent of armed retainers ready to enforce theirlord's will. A young man serving in a military capacity, separate from the entourage that constituted a noble'sfamiliaor "household", might be termed avavasorin documents.[citation needed]

Civic patronage

[edit]

Several influential Romans, such asCaesarandAugustus,established client–patron relationships in conquered regions. This can be seen in Caesar’s relations with theAeduiofGaulwherein he was able to restore their influence over the other Gallic tribes who were once their clients. Hereafter he was asked on several occasions to serve the duties of a patron by the Aedui and was thus regarded by many in Rome as the patron of the Aedui.[21]

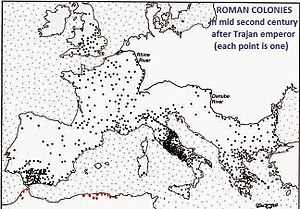

Augustus establishedcoloniesin all parts of the empire during his conquests which extended his influence to its furthest reaches. He also made many acts of kindness to the whole of Rome at large, including food and monetary handouts, as well as settling soldiers in new colonies that he sponsored, which indebted a great many people to him.[6]Through these examples, Augustus altered the form of patronage to one that suited his ambitions for power, encouraging acts that would benefit Roman society over selfish interests.[21]Although rare, it was possible for women to be patronesses.[23]

Patronage and its many forms allowed for a minimal form of administration bound by personal relations between parties and thus in thelate Republicpatronage served as a model for ruling.[21][24]Conquerors orgovernorsabroad established personal ties as patron to whole communities, ties which then might be perpetuated as a family obligation.[25]One such instance was the Marcelli's patronage of theSicilians,asClaudius Marcellushad conqueredSyracuseand Sicily.[26]

Extendingrightsorcitizenshiptomunicipalitiesorprovincialfamilies was one way to add to the number of one's clients for political purposes, asPompeius Strabodid among theTranspadanes.[27]This form of patronage contributed to the new role created byAugustusas sole ruler after the collapse of the Republic, when he cultivated an image as the patron of theEmpireas a whole.

Various professional and other corporations, such ascollegiaandsodalitates,awarded statutory titles such aspatronusorpater patratusto benefactors.

See also

[edit]- Client kingdoms and tribes

Chronologically:

- Hasmoneans:kings of Judea, the last of which were clients of the Roman republic

- Herod the Greatof Judea and his descendants

- Ghassanids,the: client tribe of the Byzantine Empire

References

[edit]- ^Quinn, Kenneth (1982). "Poet and Audience in the Augustan Age". In Haase, Wolfgang (ed.).Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt.Vol. 30/1. p. 117.doi:10.1515/9783110844108-003.ISBN978-3-11-008469-6.

- ^Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879)..The American Cyclopædia.

- ^Pollard, Elizabeth (2015).Worlds Together, Worlds Apart concise edition vol. 1.New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 253.ISBN9780393250930.

- ^Dillon, Matthew;Garland, Lynda(2005).Ancient Rome: From the Early Republic to the Assassination of Julius Caesar.Routledge.p. 87.ISBN9780415224581.

- ^"Patronage in Politics | Roman Patronage in Society, Politics, and Military".sites.psu.edu.Retrieved2020-03-10.

- ^abcMathisen, Ralph W., 1947- (2019).Ancient Roman civilization: history and sources, 753 BCE to 640 CE.Based on (work): Mathisen, Ralph W., 1947-, Based on (work): Mathisen, Ralph W., 1947-. New York, NY. pp. 64–65, 252–255.ISBN978-0-19-084960-3.OCLC1038024098.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^"Societal Patronage | Roman Patronage in Society, Politics, and Military".sites.psu.edu.Retrieved2020-03-10.

- ^Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920)..Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^Tuck, Steven L. (2010).Pompeii: daily life in an ancient Roman city.Teaching Company. p. 92.OCLC733795148.

- ^abMuirhead, James; Clay, Agnes Muriel (1911)..InChisholm, Hugh(ed.).Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^Twelve Tables8.10; Dillon and Garland,Ancient Rome,p. 87.

- ^Karl-J. Hölkeskamp,Reconstructing the Roman Republic: An Ancient Political Culture and Modern Research(Princeton University Press, 2010), pp. 33–35; Emilio Gabba,Republican Rome: The Army and the Allies,translated by P.J. Cuff (University of California Press, 1976), p. 26.

- ^Carlin A. Barton,The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster(Princeton University Press, 1993), pp. 176–177.

- ^Covino, Ralph (November 2006)."K. Verboven, The Economy of Friends. Economic Aspects of Amicitia and Patronage in the Late Republic. Brussels: Latomus, 2002. Pp. 399. ISBN 2-87031-210-5. €54.00".Journal of Roman Studies.96:236–237.doi:10.1017/S0075435800001118.ISSN0075-4358.S2CID162385287.

- ^Quinn, "Poet and Audience in the Augustan Age," p. 118.

- ^Dillon and Garland,Ancient Rome,p. 87.

- ^Quinn, "Poet and Audience in the Augustan Age," p. 116.

- ^J.A. Crook,Consilium Principis: Imperial Councils and Counsellors from Augustus to Diocletian(Cambridge University Press, 1955), p. 22; Dillon and Garland,Ancient Rome,p. 87; Koenraad Verboven, "Friendship among the Romans," inThe Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World(Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 413–414.

- ^Fergus Millar,"The Political Character of the Classical Roman Republic, 200–151 B.C.," inRome, the Greek World, and the East: The Roman Republic and the Augustan Revolution(University of North Carolina Press, 2002), p. 137, citing also the "major re-examination" ofclientelaby N. Rouland,Pouvoir politique et dépendance personnelle(1979), pp. 258–259.

- ^Millar, "The Political Character of the Classical Roman Republic," p. 137.

- ^abcdeNicols, John, Ph.D. (2 December 2013).Civic patronage in the Roman Empire.Leiden. pp. 21–35, 29, 69, 90.ISBN978-90-04-26171-6.OCLC869672373.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Oxford Classical Dictionary "patronus"

- ^Hemelrijk, Emily A. (2004)."City Patronesses in the Roman Empire".Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte.53(2): 209–245.ISSN0018-2311.JSTOR4436724.

- ^Cicero,De officiis1.35.

- ^Erich S. Gruen,"Patrociniumandclientela,"inThe Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome(University of California Press, 1986), vol. 1, pp. 162–163.

- ^Gilman, D. C.;Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905)..New International Encyclopedia(1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^A.T. Fear,Rome and Baetica "Urbanization in Southern Spain c. 50 BC–AD 150(Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 142.

Further reading

[edit]- Badian, Ernst. 1958.Foreign Clientelae (264–70 B.C.).Oxford: Clarendon.

- Bowditch, Phebe Lowell. 2001.Horace and the Gift Economy of Patronage.Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of Carolina Press.

- Busch, Anja, John Nicols, and Franceso Zanella. 2015. "Patronage".Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum,26:1109–1138.

- Damon, Cynthia. 1997.The Mask of the Parasite: A Pathology of Roman Patronage.Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press.

- de Blois, Lucas. 2011. "Army and General in the Late Roman Republic". InA Companion to the Roman Army.Edited by Paul Erdkamp, 164–179. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Eilers, Claude. 2002. Roman Patrons of Greek Cities. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Gold, Barbara K. 1987.Literary Patronage in Greece and Rome.Chapel Hill and London: Univ. of North Carolina Press.

- Konstan, David. 2005. "Friendship and Patronage". InA Companion to Latin Literature.Edited by Stephen Harrison, 345–359. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lomas, Kathryn, and Tim Cornell, eds. 2003."Bread and Circuses": Euergetism and Municipal Patronage in Roman Italy.London: Routledge.

- Nauta, Ruurd R. 2002.Poetry for Patrons: Literary Communication in the Age of Domitian.Leiden, The Netherlands, and Boston: Brill.

- Nicols, John. 2014.Civic Patronage in the Roman Empire.Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Saller, Richard P. 1982.Personal Patronage Under the Early Empire.Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Verboven, Koenraad. 2002.The Economy of Friends: Economic Aspects of Amicitia and Patronage in the late Roman Republic.Brussels: Latomus.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew, ed. 1989.Patronage in Ancient Society.London: Routledge.

External links

[edit]- The Roman Client (Smith's Dictionary, 1875) atLacusCurtius

- .The American Cyclopædia.1879.