Paul Taylor (choreographer)

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(August 2018) |

Paul Taylor | |

|---|---|

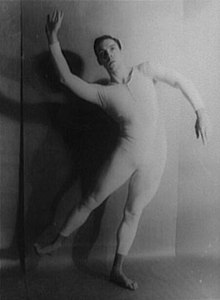

Taylor in 1960, photo byCarl Van Vechten | |

| Born | July 29, 1930 |

| Died | August 29, 2018(aged 88) Manhattan, New York,U.S. |

| Education | Juilliard School(B.S.1953) |

| Occupation | choreographer |

| Years active | 1954–2018 |

Paul Belville Taylor Jr.(July 29, 1930 – August 29, 2018) was an American dancer and choreographer. He was one of the last living members of the third generation of America's modern dance artists.[1]He founded thePaul Taylor Dance Companyin 1954 in New York City.

Early life and education[edit]

Taylor was born inWilkinsburg,Pennsylvania, to Paul Belville Taylor Sr., a physicist,[2]and to the former Elizabeth Rust Pendleton.[3]He grew up in and aroundWashington, DC.By his teens, he had grown to more than six feet in height. He was a student of painting and swam and competed on the swim team, for which he was the recipient of a swimming scholarship, atSyracuse Universityin the late 1940s. Upon discovering dance through books at the school library, Taylor created his first piece of choreography on Syracuse University Dance department students, which was entitledHobo Ballet.Taylor then transferred toJuilliard,[4]where he earned aB.S.degree in dance in 1953[5]under directorMartha Hill.It is Taylor's dedication to swimming and other widely varied experiences that has been said to have taught him the commitment imperative to a successful dance career and allowed him to develop his unique and diverse dance aesthetic.[6]

Career[edit]

In 1954 Taylor assembled a small company of dancers and began making his own works. A commanding performer despite his late start, he joined theMartha Graham Dance Companyin 1955 for the first of seven seasons as soloist where he created the role of the evilAegisthusin Graham'sClytemnestra,as well as other roles including inAcrobats of God and Alcestis, Visionary Recital, One More Gaudy Night,andPhaedra.All the while he was continuing to choreograph on his own small troupe. He also worked with the choreographersDoris Humphrey,Charles Weidman,José LimónandJerome Robbins.In 1959 he was invited byGeorge Balanchineto be a guest artist withNew York City Ballet,performing hisEpisodes.[7]

Taylor's early choreographic projects have been noted as distinctly different from the modern, physical works he would come to be known for later, and have even invited comparison to the conceptual performances of theJudson Dance Theatrein the 1960s. Taylor worked closely with painterRobert Rauschenbergwho is said to have created the paintings that inspired Taylor's choreography for several pieces includingThree EpitaphsandSeven New Dances.Specifically, Rauschenberg's series of “white” paintings resulted inJohn Cage’s composition,4’33”,for which Taylor’s pieceDuet(1957), was inspired.Duetwas part of Taylor’sSeven New Dancesconcert which became Taylor’s first claim to fame due to this piece that was deemed controversial. DuringDuet,Taylor and dancer Toby Glanternik remained completely motionless as the pianist played Cage's "non score". On the same program was a work calledEpic,in which Taylor moved slowly across the stage in a business suit while a recorded time announcement played in the background. TheDance ObservercriticLouis Horstpublished a blank column that stated only the location and date of Taylor’s performance as a review in November 1957 as a response toDuet,after whichMartha Grahamcalled him a "naughty boy."[6]

After the debut of Taylor’sSeven New Dances,Taylor continued choreographing new works which led to the completion of two European tours and ten new dances, all while still dancing with the Graham company. The turning point in Taylor’s choreographic career came with the premier of his plotless workAureole(1962), at the 1962American Dance Festival,the success of which convinced him to finally leave the Graham company to pursue choreographic work with his group of dancers full time. WithAureole,he departed from such an avant-garde aesthetic. The performance was still intended to provoke dance critics, as he cheekily set his modern movements not to contemporary music but to a baroque score. A choreographer as concerned with subject matter as he was with form, many of Taylor's pieces and movements are pointedlyaboutsomething. Some movements relate to his fascination with insects and the way they move. Other movements are influenced by his love of swimming. While he may propel his dancers through space for the sheer beauty of it, he has frequently used them to illuminate such profound issues as war, piety, spirituality, sexuality, morality and mortality. He is perhaps best known for his 1975 dance,Esplanade.InEsplanadeTaylor was fascinated with the everyday movement that people enacted on a daily basis—from running to sliding, to walking, jumping and falling. The five-section work is set to movements from two of J.S. Bach's violin Concertos. Taylor’s fascination with pedestrian movement continued through and beyondEsplanadeas he was obsessed with the differences in different dancers’ bodies, or how a simple change in timing, position, or facing, can transform the gesture of everyday movement into dance. For example, Taylor highlighted the nuances in performances of different dancers in his piecePolaris(1976), where the dance featured two sections with identical choreography but two completely different casts.[6]

Another well-known work of his isPrivate Domain(1969). Taylor was intrigued by the idea of perspective and the relationship of reality and appearance. InPrivate Domain,Taylor commissioned a set by renowned visual artist Alex Katz, whose rectangular panels obstructed the audience from seeing a portion of the stage depending on their vantage points. The seen and unseen relationship that the audience experienced was well received. In another work,Lost, Found, and Lost(1982) Taylor again showed his interest in pedestrian movement. In one section, dancers move one by one into the wing as they are waiting on a slow-moving line.

Taylor choreographed his own version ofThe Rite of Springin 1980 that he namedLe Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal).[8]Accompanied by a two-piano version of the originalStravinskyscore,The Rehearsalis a detective story complete with gangsters and kidnappings, but Taylor balanced his version with an ode to the original. In one scene a grieving mother echoes the Chosen Maiden fromNijinsky's version. This balance of old and new was widely praised, in addition to the challenging technical demands of the movement.[9]

Other well-known and highly regarded or controversial Taylor works includeBig Bertha(1970),Airs(1978),Arden Court(1981),Sunset(1983),Last Look(1985),Speaking in Tongues(1988),Brandenburgs(1988),Company B(1991),Piazzolla Caldera(1997),Black Tuesday(2001),Promethean Fire(2002), andBeloved Renegade(2008). Some of these dances, performed by thePaul Taylor Dance Company,are also licensed by such companies as theRoyal Danish Ballet,Miami City Ballet,American Ballet TheatreandAlvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

Many scholars and dance critics have established a categorization of Taylor's works and identified patterns surrounding his choreographic development. Following Taylor's first major successAureole(1962), Taylor's next commission for theAmerican Dance FestivalwasScudorama(1963), which provided a stark contrast to Taylor's previous work. This prompted scholars to identify a light/dark pattern in Taylor's choreography due toScudorama’s apparent representation of evil in comparison toAureole’s lyrical, sunny nature. This categorization that arose due to the uncommon versatility of Taylor’s choreography continued with critics placing Taylor worksAirs(1978),Esplanade(1975),Arden Court(1981), andMercuric Tidings(1982) in the “light” category, andBig Bertha(1970),Last Look(1985), andSpeaking in Tongues(1988) in the “dark” category. Some scholars have argued that Taylor's works cannot be confined to two distinct categories though as he has also created humorous and witty, romantic, and movement centered works with the piecesPiece Period(1962),Roses(1985), andImages(1977) respectively, while also in some cases diverging from his typical plotlessness and creating story centric pieces such asSnow White(1983).[10]

Taylor collaborated with artists such asRobert Rauschenberg,Jasper Johns,Ellsworth Kelly,Alex Katz,Tharon Musser,Thomas Skelton,Gene Moore,John Rawlings,William Ivey Long,Jennifer Tipton,Santo Loquasto,James F. Ingalls,Donald York andMatthew Diamond.His career and creative process has been much discussed, as he is the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentaryDancemaker,and author of the autobiographyPrivate Domainand aWall Street Journalessay, "Why I Make Dances."[11]

Recognition[edit]

Taylor was a recipient of theKennedy Center Honorsin 1992 and received anEmmy AwardforSpeaking in Tongues,produced byWNET/New York the previous year. In 1993 he was awarded theNational Medal of Artsby United States PresidentBill Clinton.He received theAlgur H. MeadowsAward for Excellence in the Arts in 1995 and was named one of 50 prominent Americans honored in recognition of their outstanding achievement by the Library of Congress's Office of Scholarly Programs. He is the recipient of threeGuggenheim Fellowshipsand honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degrees fromCalifornia Institute of the Arts,Connecticut College,Duke University,The Juilliard School,Skidmore College,theState University of New York at Purchase,Syracuse UniversityandAdelphi University.Taylor's Awards for lifetime achievement include aMacArthur Foundation Fellowship– often called the "genius award" – and theSamuel H. ScrippsAmerican Dance Festival Award. Other awards include the New York State Governor's Arts Award and the New York City Mayor's Award of Honor for Art and Culture. In 1989 Taylor was elected one of ten honorary American members of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.

Having been elected to knighthood by the French government as Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1969 and elevated to Officier in 1984 and Commandeur in 1990, Taylor was awarded France's highest honor, the Légion d'Honneur, for exceptional contributions to French culture, in 2000.

Private Domain,originally published byAlfred A. Knopfand re-released by North Point Press and later by theUniversity of PittsburghPress, was nominated by the National Book Critics Circle as the most distinguished biography of 1987.Dancemaker,Matthew Diamond's award-winning feature-length film about Taylor, was hailed by Time as "perhaps the best dance documentary ever."[12]Taylor'sFacts and Fancies: Essays Written Mostly for Fun,was published by Delphinium in 2013.

The 2019American Dance Festival's season, its 86th, was dedicated to Paul Taylor.

Paul Taylor Dance Company[edit]

The choreographer's works, totaling 147, are performed by the 16-member Paul Taylor Dance Company and dance companies throughout the world.

Of his works, 50 are documented inLabanotation.In each completed score there is a section "Introductory Material," which includes topics such as: Casts, Stylistic Notes, as well as other Production information.

In 1992, thePaul Taylor Dance Companyin conjunction with theNational Endowment for the Artslaunched the Repertory Preservation Project which was centered around the documentation of thirty of Taylor's dances, including lost works such as fromSeven New Dances.This was made possible with the grant of $850,000 that was awarded to Taylor's company, and the project led to the birth of the company Taylor 2, a junior company to the main Paul Taylor Dance Company, which allowed these dancers to preserve Taylor's works through performance.[6]

A 2015 documentary titledPaul Taylor: Creative Domainshowcased hiscreative process.It was described as "a fly-on-the-wall depiction of the 2010 creation ofThree Dubious Memories,his 133rd modern-dance piece for the eponymous company that he founded over 60 years ago. "[13]

Paul Taylor American Modern Dance[edit]

In 2015, Taylor began a new program, calledPaul Taylor American Modern Dance,[14]in which works of modern dance by choreographers other than Taylor—performed by dancers practiced in those styles—are included in the company's annual season at the Koch Theater atLincoln Center.In addition, contemporary choreographers receive commissions to create new works on the Taylor company. Thus far, dances byDoris Humphrey,Shen Wei,Merce Cunningham,Martha Graham,Donald McKayle,andTrisha Brownhave been presented. New commissions by Doug Elkins,Larry Keigwin,Lila York, Bryan Arias,Doug Varone,Margie Gillis,Pam Tanowitz,andKyle Abrahamhave been set on and danced byPaul Taylor Dance Company.Since 2015, live music has been performed on every program by theOrchestra of St. Luke's.

Death[edit]

Taylor died ofrenal failureon August 29, 2018, at aManhattanhospital at the age of 88.[15]

Selected works[edit]

- Circus Polka (1955)

- 3 Epitaphs (1956)

- Seven New Dances (1957)

- Rebus (1958)

- Tablet (1960)

- Fibers (1961)

- Junction (1961)

- Aureole (1962)

- La Negra (1963)

- Scudorama (1963)

- Party Mix (1963)

- The Red Room (1964)

- Duet (1964)

- Post Meridian (1965)

- Orbs (1966)

- Lento (1967)

- Public Domain (1968)

- Private Domain (1969)

- Churchyard (1969)

- Big Bertha (1970)

- Fetes (1971)

- So Long Eden (1972)

- Noah's Minstrels (1973)

- American Genesis (1973)

- Sports and Follies (1974)

- Esplanade (1975)

- Runes (1975)

- Cloven Kingdom (1976)

- Polaris (1976)

- Images (1977)

- Dust (1977)

- Airs (1978)

- Nightshade (1979)

- Profiles (1979)

- Le Sacre Du Printemps (1980)

- Arden Court (1981)

- House of Cards (1981)

- Mercuric Tidings (1982)

- Sunset (1983)

- Equinox (1983)

- Roses (1985)

- Musical Offering (1986)

- Counterswarm (1988)

- Danbury Mix (1988)

- The Sorcerer's Sofa (1989)

- Fact & Fancy (1991)

- Company B (199

- Spindrift (1993)

- Prim Numbers (1997)

- Eventide (1997)

- Piazzola Caldera (1997)

- The Word (1998)

- Oh, You Kid! (1999)

- Cascade (1999)

- Dandelion Wine (2000)

- Black Tuesday (2001)

- Antique Valentine (2001)

- In The Beginning (2003)

- Le Grand Puppetier (2004)

- Spring Rounds (2004)

- Troilus and Cressida (2006)

- Lines Of Loss (2007)

- De Suenos Que Se Repiten (2007)

- Changes (2008)

- Also Playing (2009)

- Three Dubious Memories (2010)

- The Uncommitted (2011)

- To Make Crops Grow (2012)

- Perpetual Dawn (2013)

- Sea Lark (2014)

- Death and the Damsel (2015)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed."Modern Dance - Later Dancers",Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^Berkeley, University of California (30 August 2018)."Register...: With announcements".The University Press – via Google Books.

- ^MacAulay, Alastair (30 August 2018)."Paul Taylor Dies at 88; Brought Poetry and Lyricism to Modern Dance".The New York Times.

- ^Taylor, Paul (1988).Private Domain.San Francisco: North Print Pages.

- ^"Current and New Donors Offer Generous Support".Juilliard Journal.Juilliard School.April 2010.

- ^abcdInternational encyclopedia of dance: a project of Dance Perspectives Foundation, Inc.Selma Jeanne Cohen, Dance Perspectives Foundation. New York: Oxford University Press. 1998.ISBN0-19-509462-X.OCLC37903473.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^Dunning, Jennifer (1986-05-30)."Dancer and Choreographer Restore Lost Solo".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved2019-01-14.

- ^Kane, Angela (1999). "Heroes and Villains: Paul Taylor's" Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal) "and Other American Tales".Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research.17(2): 47–72.doi:10.2307/1290838.JSTOR1290838.

- ^Kriegsman, Alan (January 13, 1980)."The Washington Post".RetrievedJanuary 16,2019.

- ^Kane, Angela (2003)."Through A Glass Darkly: The Many Sides of Paul Taylor's Choreography".Dance Research.21(2): 90–129.doi:10.3366/3594052.ISSN0264-2875.

- ^Taylor, Paul (2008-02-23)."The Choreographer on Why He Makes Dances".Wall Street Journal.ISSN0099-9660.Retrieved2019-01-14.

- ^Dance Maker.Matthew Diamond. Docu Rama, 1999. Video

- ^"Paul Taylor: Creative Domain:Film Review ".The Hollywood Reporter.12 September 2015.Retrieved29 December2015.

- ^Kourlas, Gia (2015-03-06)."Paul Taylor, at 84, Has a New Mission With American Modern Dance".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved2019-01-19.

- ^"Paul Taylor, a Giant of Modern Dance, Is Dead at 88".The New York Times.30 August 2018.Retrieved30 August2018.

External links[edit]

- Official websitePaul Taylor Dance Company

- PBS:American Masters biography

- Kennedy Center biography

- American Ballet Theatre biography

- Paul TayloratIMDb

- Paul Taylorat theInternet Broadway Database

- The Paul Taylor Dance Company Comes to Israel

- Paul Taylor interviewed onConversations from Penn State

- Brooklyn RailIn Conversation: Paul Taylor with Nancy Dalva

- 1930 births

- 2018 deaths

- American choreographers

- American male dancers

- Juilliard School alumni

- Kennedy Center honorees

- MacArthur Fellows

- American modern dancers

- Artists from Pittsburgh

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- University of Nevada, Las Vegas alumni

- American LGBT dancers

- People from Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania

- Deaths from kidney failure in New York (state)