Perfect fifth

| Inverse | perfect fourth |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Other names | diapente |

| Abbreviation | P5 |

| Size | |

| Semitones | 7 |

| Interval class | 5 |

| Just interval | 3:2 |

| Cents | |

| 12-Tone equal temperament | 700 |

| Just intonation | 701.955 |

Inmusic theory,aperfect fifthis themusical intervalcorresponding to a pair ofpitcheswith a frequency ratio of 3:2, or very nearly so.

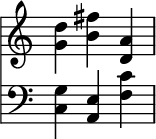

Inclassical musicfromWestern culture,a fifth is the interval from the first to the last of the first five consecutivenotesin adiatonic scale.[1]The perfect fifth (often abbreviatedP5) spans sevensemitones,while thediminished fifthspans six and theaugmented fifthspans eight semitones. For example, the interval from C to G is a perfect fifth, as the note G lies seven semitones above C.

The perfect fifth may be derived from theharmonic seriesas the interval between the second and third harmonics. In a diatonic scale, thedominantnote is a perfect fifth above thetonicnote.

The perfect fifth is moreconsonant,or stable, than any other interval except theunisonand theoctave.It occurs above therootof allmajorandminorchords (triads) and theirextensions.Until the late 19th century, it was often referred to by one of its Greek names,diapente.[2]Itsinversionis theperfect fourth.The octave of the fifth is the twelfth.

A perfect fifth is at the start of "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star";the pitch of the first" twinkle "is the root note and the pitch of the second" twinkle "is a perfect fifth above it.

Alternative definitions[edit]

The termperfectidentifies the perfect fifth as belonging to the group ofperfect intervals(including theunison,perfect fourthandoctave), so called because of their simple pitch relationships and their high degree ofconsonance.[3]When an instrument with only twelve notes to an octave (such as the piano) is tuned usingPythagorean tuning,one of the twelve fifths (thewolf fifth) sounds severely discordant and can hardly be qualified as "perfect", if this term is interpreted as "highly consonant". However, when using correctenharmonicspelling, the wolf fifth in Pythagorean tuning or meantone temperament is actually not a perfect fifth but adiminished sixth(for instance G♯–E♭).

Perfect intervals are also defined as those natural intervals whoseinversionsare also natural, where natural, as opposed to altered, designates those intervals between a base note and another note in the major diatonic scale starting at that base note (for example, the intervals from C to C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, with no sharps or flats); this definition leads to the perfect intervals being only theunison,fourth,fifth, andoctave,without appealing to degrees of consonance.[4]

The termperfecthas also been used as a synonym ofjust,to distinguish intervals tuned to ratios of small integers from those that are "tempered" or "imperfect" in various other tuning systems, such asequal temperament.[5][6]The perfect unison has apitch ratio1:1, the perfect octave 2:1, the perfect fourth 4:3, and the perfect fifth 3:2.

Within this definition, other intervals may also be called perfect, for example a perfect third (5:4)[7]or a perfectmajor sixth(5:3).[8]

Other qualities[edit]

In addition to perfect, there are two other kinds, or qualities, of fifths: thediminished fifth,which is onechromatic semitonesmaller, and theaugmented fifth,which is one chromatic semitone larger. In terms of semitones, these are equivalent to thetritone(or augmented fourth), and theminor sixth,respectively.

Pitch ratio[edit]

Thejustly tunedpitch ratioof a perfect fifth is 3:2 (also known, in early music theory, as ahemiola),[10][11]meaning that the upper note makes three vibrations in the same amount of time that the lower note makes two. The just perfect fifth can be heard when aviolinis tuned: if adjacent strings are adjusted to the exact ratio of 3:2, the result is a smooth and consonant sound, and the violin sounds in tune.

Keyboard instruments such as thepianonormally use anequal-temperedversion of the perfect fifth, enabling the instrument to play in allkeys.In 12-tone equal temperament, the frequencies of the tempered perfect fifth are in the ratioor approximately 1.498307. An equally tempered perfect fifth, defined as 700cents,is about two cents narrower than a just perfect fifth, which is approximately 701.955 cents.

Keplerexploredmusical tuningin terms of integer ratios, and defined a "lower imperfect fifth" as a 40:27 pitch ratio, and a "greater imperfect fifth" as a 243:160 pitch ratio.[12]His lower perfect fifth ratio of 1.48148 (680 cents) is much more "imperfect" than the equal temperament tuning (700 cents) of 1.4983 (relative to the ideal 1.50).Hermann von Helmholtzuses the ratio 301:200 (708 cents) as an example of an imperfect fifth; he contrasts the ratio of a fifth in equal temperament (700 cents) with a "perfect fifth" (3:2), and discusses the audibility of thebeatsthat result from such an "imperfect" tuning.[13]

Use in harmony[edit]

W. E. Heathcote describes the octave as representing the prime unity within the triad, a higher unity produced from the successive process: "first Octave, then Fifth, then Third, which is the union of the two former".[14]Hermann von Helmholtz argues that some intervals, namely the perfect fourth, fifth, and octave, "are found in all the musical scales known", though the editor of the English translation of his book notes the fourth and fifth may be interchangeable or indeterminate.[15]

The perfect fifth is a basic element in the construction of major and minortriads,and theirextensions.Because these chords occur frequently in much music, the perfect fifth occurs just as often. However, since many instruments contain a perfect fifth as anovertone,it is not unusual to omit the fifth of a chord (especially in root position).

The perfect fifth is also present inseventh chordsas well as "tall tertian" harmonies (harmonies consisting of more than four tones stacked in thirds above the root). The presence of a perfect fifth can in fact soften thedissonantintervals of these chords, as in themajor seventh chordin which the dissonance of a major seventh is softened by the presence of two perfect fifths.

Chords can also be built by stacking fifths, yielding quintal harmonies. Such harmonies are present in more modern music, such as the music ofPaul Hindemith.This harmony also appears inStravinsky'sThe Rite of Springin the "Dance of the Adolescents" where four Ctrumpets,apiccolo trumpet,and onehornplay a five-tone B-flat quintal chord.[16]

Bare fifth, open fifth, or empty fifth[edit]

A bare fifth, open fifth or empty fifth is a chord containing only a perfect fifth with no third. The closing chords ofPérotin'sViderunt omnesandSederunt Principes,Guillaume de Machaut'sMesse de Nostre Dame,theKyrieinMozart'sRequiem,and the first movement ofBruckner'sNinth Symphonyare all examples of pieces ending on an open fifth. These chords are common inMedieval music,sacred harpsinging, and throughoutrock music.Inhard rock,metal,andpunk music,overdriven or distortedelectric guitarcan make thirds sound muddy while the bare fifths remain crisp. In addition, fast chord-based passages are made easier to play by combining the four most common guitar hand shapes into one. Rock musicians refer to them aspower chords.Power chords often include octave doubling (i.e., their bass note is doubled one octave higher, e.g. F3–C4–F4).

Anempty fifthis sometimes used intraditional music,e.g., in Asian music and in someAndean musicgenres of pre-Columbian origin, such ask'antuandsikuri.The same melody is being led by parallel fifths and octaves during all the piece.

Western composers may use the interval to give a passage an exotic flavor.[17]Empty fifths are also sometimes used to give acadencean ambiguous quality, as the bare fifth does not indicate a major or minor tonality.

Use in tuning and tonal systems[edit]

The just perfect fifth, together with theoctave,forms the basis ofPythagorean tuning.A slightly narrowed perfect fifth is likewise the basis formeantonetuning.[citation needed]

Thecircle of fifthsis a model ofpitch spacefor thechromatic scale(chromatic circle), which considers nearness as the number of perfect fifths required to get from one note to another, rather than chromatic adjacency.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Don Michael Randel(2003), "Interval",Harvard Dictionary of Music,fourth edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press): p. 413.

- ^William Smith;Samuel Cheetham(1875).A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities.London: John Murray. p. 550.ISBN9780790582290.

- ^Piston, Walter;DeVoto, Mark (1987).Harmony(5th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 15.ISBN0-393-95480-3..Octaves, perfect intervals, thirds, and sixths are classified as being "consonant intervals", but thirds and sixths are qualified as "imperfect consonances".

- ^Kenneth McPherson Bradley (1908).Harmony and Analysis.C. F. Summy. p. 17.

- ^Charles Knight(1843).Penny Cyclopaedia.Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. p. 356.

- ^John Stillwell(2006).Yearning for the Impossible.A. K. Peters. p.21.ISBN1-56881-254-X.

perfect fifth imperfect fifth tempered.

- ^Llewelyn Southworth Lloyd (1970).Music and Sound.Ayer Publishing. p. 27.ISBN0-8369-5188-3.

- ^John Broadhouse (1892).Musical Acoustics.W. Reeves. p.277.

perfect major sixth ratio.

- ^abJohn Fonville(Summer 1991). "Ben Johnston's Extended Just Intonation: A Guide for Interpreters ".Perspectives of New Music.29(2): 109 (106–137).doi:10.2307/833435.JSTOR833435.

- ^ Willi Apel(1972)."Hemiola, hemiolia".Harvard Dictionary of Music(2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 382.ISBN0-674-37501-7.

- ^Randel, Don Michael,ed. (2003)."Hemiola, hemiola".The Harvard Dictionary of Music: Fourth Edition.Harvard Dictionary of Music(4th ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 389.ISBN0-674-01163-5.

- ^Johannes Kepler(2004).Stephen Hawking(ed.).Harmonies of the World.Running Press. p. 22.ISBN0-7624-2018-9.

- ^Hermann von Helmholtz(1912).On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music.Longmans, Green. pp.199,313.ISBN9781419178931.

perfect fifth imperfect fifth Helmholtz tempered

- ^W. E. Heathcote (1888), "Introductory Essay", inMoritz Hauptmann,The Nature of Harmony and Metre,translated and edited by W. E. Heathcote (London: Swan Sonnenschein), p. xx.

- ^Hermann von Helmholtz(1912).On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music.Longmans, Green. p.253.ISBN9781419178931.

perfect fifth imperfect fifth Helmholtz tempered

- ^Piston & DeVoto 1987,pp. 503–505.

- ^Scott Miller, "InsideThe King and I",New Line Theatre,accessed December 28, 2012

![{\displaystyle ({\sqrt[{12}]{2}})^{7}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bb23db3674c3081c7995b2e899d4d6c8f36159bb)