Peter O'Toole

Peter O'Toole | |

|---|---|

O'Toole in 1970 | |

| Born | Peter Seamus O'Toole 2 August 1932 |

| Died | 14 December 2013(aged 81) St John's Wood,London, England |

| Alma mater | Royal Academy of Dramatic Art |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1954–2012 |

| Notable work | Full list |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Karen Brown (1982–1988) |

| Children | 3, includingKate |

| Awards | Full list |

Peter Seamus O'Toole(/oʊˈtuːl/;2 August 1932 – 14 December 2013) was an English actor. Known for his leading roles on stage and screen, he received several accolades including theAcademy Honorary Award,aBAFTA Award,aPrimetime Emmy Award,and fourGolden Globe Awardsas well as nominations for aGrammy Awardand aLaurence Olivier Award.

O'Toole started his training at theRoyal Academy of Dramatic Art(RADA) in London and began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as aShakespeareanactor at theBristol Old Vicand with theEnglish Stage Company.In 1959, he made hisWest Enddebut inThe Long and the Short and the Tall,and played thetitle roleinHamletin theNational Theatre's first production in 1963. Excelling on stage, O'Toole was known for his "hellraiser" lifestyle off it.[2]He received a nomination for theLaurence Olivier Award for Best Comedy Performancefor his portrayal ofJeffrey Bernardin the playJeffrey Bernard Is Unwell(1990).

Making his film debut in 1959, O'Toole received his firstAcademy Award for Best Actornomination for portrayingT. E. Lawrencein the historical epicLawrence of Arabia(1962). He was further Oscar-nominated for playingKing Henry IIin bothBecket(1964) andThe Lion in Winter(1968), a public school teacher inGoodbye, Mr. Chips(1969), aparanoid schizophreniainThe Ruling Class(1972), a war veteran turnedstunt maninThe Stunt Man(1980), a film actor inMy Favorite Year(1982), and an elderly man inVenus(2006). He holds the record for the most Oscar nominations for acting without a win (tied withGlenn Close). In 2002, he was awarded theAcademy Honorary Awardfor his career achievements.[3]

O'Toole has also starred in films such asWhat's New Pussycat?(1965),How to Steal a Million(1966),Man of La Mancha(1972),Caligula(1979),Zulu Dawn(1979), andSupergirl(1984), with supporting roles inThe Last Emperor(1987),Bright Young Things(2003),Troy(2004),Stardust(2007), andDean Spanley(2008). He also voiced Anton Ego, the restaurant critic inPixar's animated filmRatatouille(2007). On television, he received thePrimetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Limited Series or Moviefor his portrayal of BishopPierre Cauchonin theCBSminiseriesJoan of Arc(1999). He was Emmy-nominated for his performances asLucius Flavius Silvain the ABC miniseriesMasada(1981), andPaul von Hindenburgin the miniseriesHitler: The Rise of Evil(2003).

Early life and education

Peter Seamus O'Toole was born on 2 August 1932, the son of Constance Jane Eliot (née Ferguson), a Scottish nurse,[4]and Patrick Joseph "Spats" O'Toole, an Irish metal plater, football player, andbookmaker.[5][6][7][8]O'Toole claimed he was not certain of his birthplace or date, stating in his autobiography that he accepted 2 August as his birth date but had birth certificates from England and Ireland. Records from the Leeds General Register Office confirm he was born atSt James's University HospitalinLeeds,Yorkshire, England, on 2 August 1932.[1]

O'Toole had an elder sister named Patricia and grew up in the south Leeds suburb ofHunslet.When he was one year old, his family began a five-year tour of major racecourse towns in Northern England. He and his sister were brought up in their father's Catholic faith.[9]O'Toole wasevacuatedfrom Leeds early in the Second World War,[10]and went to a Catholic school for seven or eight years: St Joseph's Secondary School in Hunslet, Leeds.[11]He later said, "I used to be scared stiff of the nuns: their whole denial of womanhood—the black dresses and the shaving of the hair—was so horrible, so terrifying. [...] Of course, that's all been stopped. They're sipping gin and tonic in theDublinpubs now, and a couple of them flashed their pretty ankles at me just the other day. "[12]

Upon leaving school, O'Toole obtained employment as a trainee journalist and photographer on theYorkshire Evening Post,[13]until he was called up fornational serviceas asignallerin theRoyal Navy.[14]As reported in a radio interview in 2006 onNPR,he was asked by an officer whether he had something he had always wanted to do. His reply was that he had always wanted to try being either a poet or an actor.[15]

He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in London from 1952 to 1954 on a scholarship. This came after being rejected by theAbbey Theatre's drama school in Dublin by the directorErnest Blythe,because he could not speak theIrish language.[16]At RADA, he was in the same class asAlbert Finney,Alan BatesandBrian Bedford.[17]O'Toole described this as "the most remarkable class the academy ever had, though we weren't reckoned for much at the time. We were all considereddotty."[18]

Acting career

1954–1961: Early work and rise to prominence

O'Toole began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as aShakespeareanactor at theBristol Old Vicand with theEnglish Stage Company,before making his television debut in 1954. He played a soldier in an episode ofThe Scarlet Pimpernelin 1954. He was based at the Bristol Old Vic from 1956 to 1958, appearing in productions ofKing Lear,The Recruiting Officer,Major Barbara,Othello,andThe Slave of Truth(all 1956). He was Henry Higgins inPygmalion,Lysander inA Midsummer Night's Dream,Uncle Gustave inOh! My Papa!,[19]and Jimmy Porter inLook Back in Anger(all 1957). O'Toole was Tanner in Shaw'sMan and Superman(1958), a performance he reprised often during his career.[citation needed]He was also inHamlet,The Holiday,Amphitryon '38,andWaiting for Godot(as Vladimir; all 1958). He hopedThe Holidaywould take him to the West End but it ultimately folded in the provinces; during that show he metSiân Phillipswho became his first wife.[20]

O'Toole continued to appear on television, being in episodes ofArmchair Theatre( "The Pier", 1957), andBBC Sunday-Night Theatre( "The Laughing Woman", 1958) and was in the TV adaptation ofThe Castiglioni Brothers(1958). He made his London debut in a musical,Oh, My Papa.[21]He gained fame on theWest Endin the playThe Long and the Short and the Tall,performed at the Royal Court beginning in January 1959. His co-stars includedRobert ShawandEdward Judd,and it was directed byLindsay Anderson.O'Toole reprised his performance for television onTheatre Nightin 1959 (although he did not appear in the1961 film version). The show transferred to the West End in April and won O'Toole Best Actor of the Year in 1959.[22]

O'Toole was in much demand. He reportedly received five offers of long-term contracts but turned them down.[21]His first role was a small role in Disney's version ofKidnapped(1960), playing the bagpipes oppositePeter Finch.[23]His second feature wasThe Savage Innocents(1960) withAnthony Quinnfor directorNicholas Ray.With his then wife Sian Phillips he didSiwan: The King's Daughter(1960) for TV. In 1960 he had a nine-month season at theRoyal Shakespeare Companyin Stratford, appearing inThe Taming of the Shrew(as Petruchio),The Merchant of Venice(as Shylock) andTroilus and Cressida(as Thersites). He could have made more money in films but said "You've got to go to Stratford when you've got the chance."[24]

O'Toole had been seen inThe Long and the Short and the TallbyJules Buckwho later established a company with the actor.[23][25]Buck cast O'Toole inThe Day They Robbed the Bank of England(1961), a heist thriller from directorJohn Guillermin.O'Toole was billed third, beneathAldo RayandElizabeth Sellars.[26]The same year he appeared in several episodes of the TV seriesRendezvous( "End of a Good Man", "Once a Horseplayer", "London-New York" ).[27]He lost the role in the film adaptation ofLong and the Short and the TalltoLaurence Harvey.[23]"It broke my heart", he said later.[24]

1962–1972:Lawrence of Arabiaand stardom

O'Toole's major break came in November 1960 when he was chosen to play the eponymous heroT. E. Lawrencein SirDavid Lean's epicLawrence of Arabia(1962), afterAlbert Finneyreportedly turned down the part.[28]The role introduced him to a global audience and earned him the first of his eight nominations for theAcademy Award for Best Actor.He received theBAFTA Award for Best British Actor.His performance was ranked number one inPremieremagazine's list of the 100 Greatest Performances of All Time.[29]In 2003, Lawrence as portrayed by O'Toole was selected as thetenth-greatest hero in cinema historyby theAmerican Film Institute.[30]Janet MaslinofThe New York Timeswrote in 1989 "The then unknown Peter O'Toole, with his charmingly diffident manner and his hair and eyes looking unnaturally gold and blue, accounted for no small part of this film's appeal to impressionable young fans".[31]

O'Toole playedHamletunderLaurence Olivier's direction in the premiere production of theRoyal National Theatrein 1963.[32]The casting of O'Toole as the Dane was met with some controversy withMichael Gambondescribing him as a "god with bright blonde hair". On playing the role O'Toole stated he was "sick with nerves", adding "If you want to know what it's like to be lonely, really lonely, try playing Hamlet."The Timeswrote, "Mr O'Toole, like Olivier, is an electrifyingly outgoing actor, and it is a surprise to see him make his first appearance...with his features twisted into melancholy"[33]He performed inBaal(1963) at the Phoenix Theatre.[34]

Even prior to the making ofLawrence of Arabia,O'Toole announced he wanted to form a production company with Jules Buck. In November 1961 they said their company, known as Keep Films (also known as Tricolor Productions) would make a film starring Terry-Thomas,Operation Snatch.[35]In 1962 O'Toole and Buck announced they wanted to make a version ofWaiting for Godotfor £80,000.[36]The film was never made. Instead their first production wasBecket(1964), where O'Toole playedKing Henry IIopposite Richard Burton. The film, done in association withHal Wallis,was a financial success.[25][37]

O'Toole turned down the lead role inThe Cardinal(1963).[21]Instead he and Buck made another epic,Lord Jim(1965), based on the novel byJoseph Conraddirected by Richard Brooks.[25][34]He and Buck intended to follow this with a biopic ofWill Adams[38]and a film aboutthe Charge of the Light Brigade,but neither project happened.[39]Instead O'Toole went intoWhat's New Pussycat?(1965), a comedy based on a script byWoody Allen,taking over a role originally meant forWarren Beattyand starring alongsidePeter Sellers.It was a huge success.[40]He and Buck helped produceThe Party's Over(1965). O'Toole returned to the stage withRide a Cock Horseat the Piccadilly Theatre in 1965, which was harshly reviewed.[20]He made a heist film withAudrey Hepburn,How to Steal a Million(1966), directed byWilliam Wyler.He played the Three Angels in the all-starThe Bible: In the Beginning...(1966), directed byJohn Huston.In 1966 at the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin he appeared in productions ofJuno and the PaycockandMan and Superman.[20]

Sam Spiegel,producer ofLawrence of Arabia,reunited O'Toole with Omar Sharif inThe Night of the Generals(1967), which was a box office disappointment. O'Toole played in an adaptation ofNoël Coward'sPresent Laughterfor TV in 1968, and had a cameo inCasino Royale(1967). He played Henry II again inThe Lion in Winter(1968) alongsideKatharine Hepburn,and was nominated for an Oscar again – one of the few times an actor had been nominated playing the same character in different films. The film was also successful at the box office.[41]Less popular wasGreat Catherine(1968) withJeanne Moreau,an adaptation of the play byGeorge Bernard Shawwhich Buck and O'Toole co-produced.[25][42]In 1969, he played the title role in the filmGoodbye, Mr. Chips,a musical adaptation ofJames Hilton's novella,starring oppositePetula Clark.He was nominated for anAcademy Award as Best Actorand won aGolden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy.O'Toole fulfilled a lifetime ambition in 1970 when he performed on stage inSamuel Beckett'sWaiting for Godot,alongsideDonal McCann,at Dublin'sAbbey Theatre.

In other films, he played a man in love with his sister (played bySusannah York) inCountry Dance(1970). O'Toole starred in a war film for directorPeter Yates,Murphy's War(1971), appearing alongside Sian Phillips. He was reunited with Richard Burton in a film version ofUnder Milk Wood(1972) byDylan Thomas,produced by himself and Buck;Elizabeth Taylorco-starred. The film was not a popular success.[20]He received anotherAcademy Award for Best Actornomination for his performance inThe Ruling Class(1972), done for his own company.[25][20]In 1972, he played bothMiguel de Cervantesand his fictional creationDon QuixoteinMan of La Mancha,the motion picture adaptation of the1965 hit Broadway musical,oppositeSophia Loren.The film was a critical and commercial failure, criticised for using mostly non-singing actors. His singing was dubbed bytenorSimon Gilbert,[43]but the other actors did their own singing. O'Toole and co-starJames Coco,who played both Cervantes's manservant andSancho Panza,both receivedGolden Globenominations for their performances.

1973–1999: Established actor

O'Toole did not make a film for several years. He performed at the Bristol Old Vic from 1973 to 1974 inUncle Vanya,Plunder,The Apple CartandJudgement.He returned to films withRosebud(1975), a flop thriller forOtto Preminger,in which O'Toole replacedRobert Mitchumat the last minute. He followed it withMan Friday(1975), an adaptation of theRobinson Crusoestory, which was the last work from Keep Films.[37]O'Toole madeFoxtrot(1976), directed byArturo Ripstein.He was critically acclaimed for his performance inRogue Male(1976) for British television.[44]He didDead Eyed Dickson stage in Sydney in 1976.[45]Less well received wasPower Play(1978), made in Canada, andZulu Dawn(1979), shot in South Africa.[46]He touredUncle VanyaandPresent Laughteron stage. In 1979, O'Toole starred asTiberiusin the controversialPenthouse-funded biopicCaligulaacting alongsideMalcolm McDowell,Helen MirrenandJohn Gielgud.[47]

In 1980, he received critical acclaim for playing the director in the behind-the-scenes filmThe Stunt Man.[48][49]His performance earned him an Oscar nomination. He appeared in a mini-series for Irish TV,Strumpet City,in which he playedJames Larkin.He followed this with another mini-series,Masada(1981), playingLucius Flavius Silva.In 1980, he performed inMacbethat the Old Vic for $500 a week (equivalent to $1,800 in 2023), a performance that famously earned O'Toole some of the worst reviews of his career.[50][51]

O'Toole was nominated for another Oscar forMy Favorite Year(1982), a light romantic comedy about the behind-the-scenes at a 1950s TV variety-comedy show, in which O'Toole plays an ageingswashbucklingfilm star reminiscent ofErrol Flynn.He returned to the stage in London with a performance inMan and Superman(1982) that was better received than hisMacbeth.[52]He focused on television, doing an adaptation ofMan and Superman(1983),Svengali(1983),Pygmalion(1984), andKim(1984), and providing the voice ofSherlock Holmesfor a series of animated TV movies. He played inPygmalionon stage in 1984 at the West End'sShaftesbury Theatre.[53]

O'Toole returned to feature films inSupergirl(1984),Creator(1985),Club Paradise(1986),The Last Emperor(1987) as SirReginald Johnston,andHigh Spirits(1988).[54]He appeared on Broadway in an adaptation ofPygmalion(1987), oppositeAmanda Plummer.It ran for 113 performances.

He won aLaurence Olivier Awardfor his performance inJeffrey Bernard Is Unwell(1989).[55]His other appearances that decade includeUncle Silas(1989) for television. O'Toole's performances in the 1990s includeWings of Fame(1990);The Rainbow Thief(1990), with Sharif;King Ralph(1991) withJohn Goodman;Isabelle Eberhardt(1992);Rebecca's Daughters(1992), in Wales;Civvies(1992), a British TV series;The Seventh Coin(1993);Heaven & Hell: North & South, Book III(1994), for American TV; andHeavy Weather(1995), for British TV. He was in an adaptation ofGulliver's Travels(1996), playing the Emperor of Lilliput;FairyTale: A True Story(1997), playingSir Arthur Conan Doyle;Phantoms(1998), from a novel byDean Koontz;andMolokai: The Story of Father Damien(1999). He won aPrimetime Emmy Awardfor his role as Bishop Pierre Cauchon in the 1999 mini-seriesJoan of Arc.He also produced and starred in a TV adaptation ofJeffrey Bernard Is Unwell(1999).

2000–2013: Resurgence and final roles

O'Toole's work in the next decade includedGlobal Heresy(2002);The Final Curtain(2003);Bright Young Things(2003);Hitler: The Rise of Evil(2003) for TV, asPaul von Hindenburg;andImperium: Augustus(2004) asAugustus Caesar.In 2004, he playedKing PriaminTroy.In 2005, he appeared on television as the older version of legendary 18th century Italian adventurerGiacomo Casanovain theBBCdrama serialCasanova.The younger Casanova, seen for most of the action, was played byDavid Tennant,who had to wear contact lenses to match his brown eyes to O'Toole's blue. He followed it with a role inLassie(2005).

O'Toole was once again nominated for the Best Actor Academy Award for his portrayal of Maurice in the 2006 filmVenus,directed byRoger Michell,his eighth such nomination.[56]He was inOne Night with the King(2007) and co-starred in thePixaranimated filmRatatouille(2007), an animated film about a rat with dreams of becoming the greatest chef in Paris, as Anton Ego, a food critic. He had a small role inStardust(2007). He also appeared in the second season ofShowtime's drama seriesThe Tudors(2008), portrayingPope Paul III,whoexcommunicatesKing Henry VIIIfrom the church; an act which leads to a showdown between the two men in seven of the ten episodes. Also in 2008, he starred alongsideJeremy NorthamandSam Neillin the New Zealand/British filmDean Spanley,based on an Alan Sharp adaptation of Irish author Lord Dunsany's short novel,My Talks with Dean Spanley.[57]

He was inThomas Kinkade's Christmas Cottage(2008); andIron Road(2009), a Canadian-Chinese miniseries. O'Toole's final performances came inEldorado(2012) andFor Greater Glory:The True Story of Cristiada(2012). On 10 July 2012, O'Toole released a statement announcing his retirement from acting.[58]A number of films were released after his retirement and death:Decline of an Empire(2013), asGallus;andDiamond Cartel(2017).

Personal life

Personal views

While studying at RADA in the early 1950s, O'Toole was active in protesting against British involvement in theKorean War.Later, in the 1960s, he was an active opponent of theVietnam War.He played a role in the creation of the current form of the well-known Irish folk song "Carrickfergus"which he related toDominic Behan,who put it in print and made a recording in the mid-1960s.[59]

Although he lost faith inorganised religionas a teenager, O'Toole expressed positive sentiments regarding the life of Jesus Christ. In an interview forThe New York Times,he said "No one can take Jesus away from me... there's no doubt there was a historical figure of tremendous importance, with enormous notions. Such as peace." He called himself "a retired Christian" who prefers "an education and reading and facts" to faith.[60]

Ireland

The son of an Irishman, O’Toole had a strong affinity with Ireland and on occasion referred to himself as Irish: “I consider myself to be an Irishman but I have lived most of my life in England so I am fairly bogus Irish actor as such”.[61]In an interview withCharlie Rosein 1992 he said Irishness was “almost the centre of my very being” and that “Everything I think of is coloured by its history, by its literature, by its people, by its geography”. He recalls that he was “a bit of a misfit, a bit of an odd man out” but that when he went toCounty Kerry,Ireland in 1946 he realized “I wasn’t different at all”.[62]

He possessed an Irish passport and believed he may have been born inConnemara.[63]He owned a house in Ireland located inClifden,County Galway.[64]In 1969 he met future Irish presidentMichael D. Higginsand the two developed a friendship.[65]

His son Lorcan was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1983. He told his friends that he wanted him to be "raised as an Irishman".[66]

Relationships

O'Toole married Welsh actress Siân Phillips in 1959, with whom he had two daughters: actressKateand Patricia. They were divorced in 1979. Phillips later said in two autobiographies that O'Toole had subjected her to mental cruelty, largely fuelled by drinking, and was subject to bouts of extreme jealousy when she finally left him for a younger lover.[67]

O'Toole and his girlfriend, model Karen Brown,[68]had a son, Lorcan O'Toole (born 17 March 1983), when O'Toole was fifty years old. Lorcan, now an actor, was a pupil atHarrow School,boarding at West Acre from 1996.[69]

Sports

O'Toole playedrugby leagueas a child in Leeds[70]and was also arugby unionfan, attendingFive Nationsmatches with friends and fellow rugby fansRichard Harris,Kenneth Griffith,Peter FinchandRichard Burton.He was also a lifelong player, coach and enthusiast of cricket[71]and a fan ofSunderland A.F.C.[72]His support of Sunderland was passed on to him through his father, who was a labourer inSunderlandfor many years.[73]He was named their most famous fan.[74]The actor in a later interview expressed that he no longer considered himself as much of a fan following the demolition ofRoker Parkand the subsequent move to theStadium of Light.He described Roker Park as his last connection to the club and that everything "they meant to him was when they were at Roker Park".[73]

Health

Severe illness almost ended O'Toole's life in the late 1970s. His stomach cancer was misdiagnosed as resulting from his alcoholic excess.[75]O'Toole underwent surgery in 1976 to have hispancreasand a large portion of his stomach removed, which resulted ininsulin-dependentdiabetes.In 1978, he nearly died from ahematologic disease.[76]He eventually recovered and returned to work. He resided on the Sky Road, just outsideClifden,Connemara,County Galway, from 1963, and at the height of his career maintained homes in Dublin, London, and Paris (at theRitz,which was where his character supposedly lived in the filmHow to Steal a Million).[citation needed]

Interests and influences

In an interview withNPRin December 2006, O'Toole revealed that he knew all 154 ofShakespeare'ssonnets.A self-described romantic, O'Toole said of the sonnets that nothing in the English language compares with them, and that he read them daily. InVenus(2006), he recitesSonnet 18( "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" ).[77]

O'Toole wrote two memoirs.Loitering with Intent: The Childchronicles his childhood in the years leading up to the Second World War, and was aNew York TimesNotable Book of the Year in 1992. His second,Loitering With Intent: The Apprentice,is about his years spent training with a cadre of friends atRADA.[citation needed]

O'Toole was interviewed at least three times byCharlie Roseon his eponymoustalk show.In a 17 January 2007 interview, O'Toole stated that British actorEric Porterhad most influenced him, adding that the difference between actors of yesterday and today is that actors of his generation were trained for "theatre, theatre, theatre". He also believes that the challenge for the actor is "to use his imagination to link to his emotion" and that "good parts make good actors." However, in other venues (including the DVD commentary forBecket), O'Toole creditedDonald Wolfitas being his most important mentor.[78]

Death and legacy

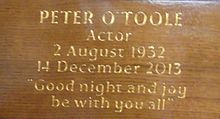

O'Toole retired from acting in July 2012 owing to a recurrence of stomach cancer.[79]He died on 14 December 2013 at theWellington HospitalinSt John's Wood,London, at the age of 81.[80]His funeral was held atGolders Green Crematoriumin London on 21 December 2013, where his body was cremated in a wicker coffin.[81]His family stated their intention to fulfil his wishes and take his ashes to the west of Ireland.[82]

On 18 May 2014, a new prize was launched in memory of Peter O'Toole at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School; this includes an annual award given to two young actors from the School, including a professional contract at Bristol Old Vic Theatre.[83]He has a memorial plaque inSt Paul's,the Actors' Church inCovent Garden,London.[citation needed]

On 21 April 2017, theHarry Ransom Centerat theUniversity of Texas at Austinannounced thatKate O'Toolehad placed her father's archive at the Humanities Research Centre.[84]The collection includes O'Toole's scripts, extensive published and unpublished writings, props, photographs, letters, medical records, and more. It joins the archives of several of O'Toole's collaborators and friends, includingDonald Wolfit,Eli Wallach,Peter Glenville,SirTom Stoppard,and DameEdith Evans.[85][86]

Acting credits and accolades

O'Toole was the recipient of numerous nominations and awards. He was offered aknighthoodbut rejected it in objection to Prime MinisterMargaret Thatcher's policies.[87][better source needed]He received fourGolden Globe Awards,oneBAFTA Award for Best British Actor(forLawrence of Arabia) and onePrimetime Emmy Award.

Academy Award nominations

O'Toole was nominated eight times for the Academy Award forBest Actor in a Leading Role,but was never able to win a competitive Oscar. In 2002,[3]the Academy honoured him with anAcademy Honorary Awardfor his entire body of work and his lifelong contribution to film. O'Toole initially balked about accepting, and wrote the Academy a letter saying that he was "still in the game" and would like more time to "win the lovely bugger outright". The Academy informed him that they would bestow the award whether he wanted it or not. He toldCharlie Rosein January 2007 that his children admonished him, saying that it was the highest honour one could receive in the filmmaking industry. O'Toole agreed to appear at the ceremony and receive his Honorary Oscar. It was presented to him byMeryl Streep,who has themost Oscar nominationsof any actor or actress (21). He joked withRobert Osborne,during an interview atTurner Classic Movies' film festival that he's the "Biggest Loser of All Time", due to his lack of an Academy Award, after many nominations.[88]

Bibliography

- Loitering with Intent: The Child(1992)

- Loitering with Intent: The Apprentice(1997)

See also

- List of British Academy Award nominees and winners

- List of actors with Academy Award nominations

- List of actors with three or more Academy Award nominations in acting categories

Notes

- ^Records from the Leeds General Register Office confirm he was born atSt James's University Hospitalon 2 August 1932.[1]

References

- ^ab"O'Toole's claims of Irish roots are blarney".Irish Independent.28 January 2007.

- ^ab"Four 'Hellraisers,' Living It Up In The Public Eye".NPR.Retrieved22 March2020.

- ^ab"To Peter O'Toole, whose remarkable talents have provided cinema history with some of its most memorable characters".75th Academy Awards.Kodak Theatre:The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 23 March 2003 [2002].Retrieved6 February2021.

- ^O'Toole, Peter.Loitering with Intent: Child(Large print edition), Macmillan London Ltd., London, 1992.ISBN1-85695-051-4;pg. 10, "My mother, Constance Jane, had led a troubled and a harsh life. Orphaned early, she had been reared in Scotland and shunted between relatives;..."

- ^"Peter O'Toole Dead: Actor Dies At Age 81".Huffington Post.15 December 2013.Retrieved19 December2013.

- ^"Peter O'Toole profile at".Film Reference.2008.Retrieved4 April2008.

- ^Murphy, Frank (31 January 2007)."Peter O'Toole, A winner in waiting".The Irish World.Archived fromthe originalon 9 May 2015.Retrieved4 April2008.

- ^"Loitering with Intent Summary – Magill Book Reviews".Enotes. Archived fromthe originalon 22 January 2013.Retrieved12 June2012.

- ^Tweedie, Neil (24 January 2007)."Too late for an Oscar? No, no, no...".The Daily Telegraph.London.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2022.Retrieved11 September2010.

- ^"Peter O'Toole: Lad from Leeds who became one of screen greats".Yorkshire Evening Post.15 December 2013. Archived fromthe originalon 26 September 2017.Retrieved17 December2013.

- ^"Obituary: Peter O'Toole, actor".The Scotsman.Retrieved22 March2020.

- ^Waldman, Alan."Tribute to Peter O'Toole".films42.Retrieved4 April2008.

- ^Lambourne, Helen (16 December 2013)."'You'll never make a reporter' editor told O'Toole ".Hold the Fronte Page.Retrieved4 August2018.

- ^Suebsaeng, Asawin (15 December 2013)."How the Royal Navy Helped the Late Peter O'Toole Become an Acting Legend".Mother Jones.Foundation for National Progress.Retrieved4 August2018.

- ^Lee, Adrian (15 December 2013)."Remembering Peter O'Toole".The Atlantic.Retrieved4 August2018.

- ^Sheehy, Michael (1969).Is Ireland Dying?: Culture and the Church in Modern Ireland.Taplinger Publishing Company. p. 141.ISBN978-0-8008-4250-5.

- ^Cochrane, Claire (27 October 2011).Twentieth-Century British Theatre: Industry, Art and Empire.Cambridge University Press. p. 212.ISBN978-1-139-50213-9.

- ^Flatley, Guy (24 July 2007)."The Rule of O'Toole".MovieCrazed.Retrieved4 April2008.

- ^"Oh! My Papa! Cast and crew".Theatricalia.Retrieved6 June2024.

- ^abcdeFlatley, Guy (17 September 1972)."Peter O'Toole, From 'Lawrence' To 'La Mancha'".The New York Times.p. D1.

- ^abcArcher, Eugene (30 September 1962). "INTRODUCTION TO AN IRISH INDIVIDUALIST".The New York Times.p. X7.

- ^Hall, Willis (2 April 1959). "Writing regional plays for a national audience".The Manchester Guardian.p. 6.

- ^abcWatts, Stephen (24 January 1960). "REPORTS ON BRITAIN'S VARIED MOVIE FRONTS".The New York Times.ProQuest115236724.

- ^abWatts, Stephen (5 February 1961). "NOTED ON BRITAIN'S FILM FRONT".The New York Times.p. X7. M.

- ^abcde"Jules Buck".The Independent on Sunday.London. 23 July 2001. Archived fromthe originalon 7 January 2008.Retrieved23 September2007.

- ^Vagg, Stephen (17 November 2020)."John Guillermin: Action Man".Filmink.

- ^Glaister, Dan (29 October 2004)."After 42 years, Sharif and O'Toole decide the time is right to get their epic act together again".The Guardian.London, UK.Retrieved3 May2012.

- ^"Albert Finney death: The actor was David Lean's first choice for Lawrence of Arabia'".The Independent.Archivedfrom the original on 26 May 2022.Retrieved21 April2020.

- ^"The 100 Greatest Movie Performances of All Time".Premiere Magazine.April 2006.

- ^"Good and Evil Rival for Top Spots in AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains".American Film Institute. 4 June 2003. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved20 December2013.

- ^"'Lawrence' Seen Whole ".The New York Times.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^"Monitor – Prince of Denmark".BBC.Retrieved9 August2020.

- ^"Hamlet, National Theatre, October 1963".The Guardian.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^ab"Dressing-room talk with a wild man of destiny— PETER O'TOOLE".The Australian Women's Weekly.Vol. 32, no. 49. 5 May 1965. p. 36.Retrieved25 November2018– via National Library of Australia.

- ^Watts, Stephen (5 November 1961). "BRITAIN'S SCREEN SCENE".The New York Times.p. X7.

- ^Weiler, A. H. (9 September 1962). "PASSING PICTURE SCENE: Film Version of 'Waiting for Godot' Planned--'Gunfighter'--Busy Lass".New York Times.p. 137.

- ^abBergan, Ronald (24 July 2001). "Obituary: Jules Buck: Film producer behind Peter O'Toole's rise to screen stardom".The Guardian.p. 20.

- ^"O'Toole's New Role to Be 'Will Adams'".Los Angeles Times.19 August 1964. p. D13.

- ^Scheuer, Philip K. (3 March 1965). "O'Toole and Harvey in Levine Brigade: Wolper on Remagen Bridge; Wise's Music Really Sounds".Los Angeles Times.p. D9.

- ^Biskind, Peter(13 December 2011).Easy Riders Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-And Rock 'N Roll Generation Save.New York City: Simon and Schuster. pp. 25–26.ISBN978-1-4391-2661-5.

- ^"The World's Top Twenty Films",Sunday Times,[London, England], 27 September 1970: 27. The Sunday Times Digital Archive. accessed 5 April 2014

- ^Marks, Sally K. (30 April 1967). "'Catherine' Plush Saga of Czarist Era ".Los Angeles Times.p. c11.

- ^"Man of La Mancha (1972) – Soundtracks".IMDb.Retrieved10 February2023.

- ^Hodgson, Clive (1 April 1978). "Television: An Interview with Mark Shivas".London Magazine.Vol. 18, no. 1. p. 68.

- ^"IN BRIEF Actors".The Canberra Times.Vol. 51, no. 14, 539. 20 November 1976. p. 7.Retrieved25 November2018– via National Library of Australia.

- ^"Canadian calls the shots at U.S. cable giant".Toronto Star.16 November 1988. p. B9.

- ^"'Caligula: The Ultimate Cut' Review: The Taming of a Screwed Production, Minus the Penthouse Taint ".Variety.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^Ebert, Roger (7 November 1980)."The Stunt Man".rogerebert.Retrieved7 March2016.

- ^Maslin, Janet (17 October 1980)."O'Toole In 'Stunt Man'".The New York Times.

- ^"Another 'Macbeth' success".The Canberra Times.Vol. 55, no. 16, 441. 30 September 1980. p. 18.Retrieved25 November2018– via National Library of Australia.

- ^Downie, Leonard, Jr. (9 September 1980)."Toil and Trouble At the Old Vic".The Washington Post.

{{cite news}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^"O'Toole role improves on his Macbeth".The Canberra Times.Vol. 57, no. 17, 224. 24 November 1982. p. 28.Retrieved25 November2018– via National Library of Australia.

- ^"Peter O'Toole: buccaneer at large".The Globe and Mail.12 May 1984. p. 8.

- ^"FILM".The Canberra Times.Vol. 63, no. 19, 414. 1 December 1988. p. 29.Retrieved25 November2018– via National Library of Australia.

- ^Gibbons, Fiachra (19 February 2000)."National upsets the form book at awards".The Guardian.Retrieved15 December2013.

- ^"A Peter O'Toole interview with USA TODAY".USA Today.Retrieved14 October2019.

- ^French, Philip (14 December 2008)."Dean Spanley".The Guardian.Retrieved18 December2013.

- ^"Peter O'Toole announces retirement from show biz".CBC.ca.10 July 2012.Retrieved10 July2012.

- ^"Harris & O'Toole – Carrickfergus video".NME.Archived fromthe originalon 15 December 2013.Retrieved15 December2013.

- ^Gates, Anita (26 July 2007)."Papal Robes, and Deference, Fit O'Toole Snugly".The New York Times.

- ^"Irish Man Bogus Irish Actor 1963".RTÉ.

- ^Guidera, Anita (22 December 2013)."Peter the Great".Irish Independent.

- ^Meagher, John (16 December 2013)."President leads tributes to Peter O'Toole, a legend fiercely proud of his Irish heritage".Irish Independent.

- ^Wapshott, Nicholas (1984).Peter O'Toole: A Biography.Beaufort Books. p. 198.

- ^"President Higgins pays tribute to 'genius' of late Peter O'Toole".The Irish Times.18 May 2014.

- ^Sellars, Robert (2015).Peter O'Toole: The Definitive Biography.Pan Macmillan. p. 272.

- ^Southern, Nathan (2008)."Peter O'Toole profile".AllRovi.MSN Movies. Archived fromthe originalon 10 March 2008.Retrieved4 April2008.

- ^"Model Karen Brown Somerville".December 2013.Retrieved15 December2013.

- ^Standing, Sarah (15 December 2013)."Remembering Peter O'Toole".GQ.Retrieved15 December2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^"O'Toole joins the rugby league actors XIII".The Roar.Retrieved19 December2013.

- ^"O'Toole bowled them over in Galway".Irish Independent.Retrieved23 December2013.

- ^"Peter O'Toole, a hell-raising dad and a lost Sunderland passion".Salut Sunderland.Archived fromthe originalon 15 December 2013.Retrieved19 December2013.

- ^ab"Peter O'Toole and a lost Sunderland passion".Archived fromthe originalon 26 March 2016.Retrieved13 September2019.

- ^Terry, Paper (23 December 2013)."Peter O'Toole Dies – Sunderland Most Famous Supporter Is Dead".Retrieved12 September2020.

- ^Leading Men: The 50 Most Unforgettable Actors of the Studio Era.Chronicle Books (Turner Classic Movies Film Guide). 2006. p. 165.

- ^Hogan, Mike (15 December 2013)."Peter O'Toole, Dead at 81, Made an Indelible Mark with Lawrence of Arabia".Vanity Fair.Retrieved4 August2018.

- ^"Peter O'Toole and a Young 'Venus'".NPR.Retrieved24 March2020.

- ^Kabatchnik, Amnon (2017).Blood on the Stage, 1600 to 1800: Milestone Plays of Murder, Mystery, and Mayhem.Rowman & Littlefield. p. 209.

- ^"President leads tributes to Peter O'Toole, a legend fiercely proud of his Irish heritage".Irish Independent.16 December 2013.Retrieved24 September2019.

- ^Booth, Robert (15 December 2013)."Peter O'Toole, star of Lawrence of Arabia, dies aged 81".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved10 February2023.

- ^"Peter O'Toole's ex-wife makes an appearance at his funeral".Express.co.uk.22 December 2013.Retrieved10 February2023.

- ^"O'Toole's ashes heading home to Ireland".Ulster Television.Archived fromthe originalon 1 January 2014.Retrieved4 January2014.

- ^"The Peter O'Toole Prize".bristololdvic.org.uk.Archived fromthe originalon 28 April 2017.Retrieved27 April2017.

- ^"Archive Acquired of Theatre and Film Actor Peter O'Toole".utexas.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 28 April 2017.Retrieved27 April2017.

- ^Brown, Mark (21 April 2017)."Peter O'Toole personal archive heads to University of Texas".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved27 April2017.

- ^Nyren, Erin."Peter O'Toole Archive Acquired by University of Texas".Variety.Retrieved27 April2017.

- ^Corliss, Richard (16 December 2013)."Peter O'Toole: Lawrence of Always".Time.Retrieved5 February2020.

- ^"Interview de Peter O'Toole".Archived fromthe originalon 29 October 2021.Retrieved3 November2016– via YouTube.

External links

- 1932 births

- 2013 deaths

- Military personnel from Leeds

- 20th-century Royal Navy personnel

- 20th-century English male actors

- 21st-century English male actors

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- Alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

- Best British Actor BAFTA Award winners

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- David di Donatello winners

- English people of Irish descent

- English people of Scottish descent

- English male film actors

- English male Shakespearean actors

- English male stage actors

- English male television actors

- English male voice actors

- Irish people of Scottish descent

- Irish male film actors

- Irish male stage actors

- Irish male television actors

- Irish male voice actors

- Male actors from Leeds

- Male actors from Yorkshire

- New Star of the Year (Actor) Golden Globe winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie Primetime Emmy Award winners

- People with type 1 diabetes

- Royal Navy sailors

- Royal Shakespeare Company members

- People from Hunslet