Photography in Canada

Photographshave been taken in the area now known asCanadasince 1839, by both amateurs and professionals. In the 19th century, commercial photography focussed onportraiture.But professional photographers were also involved in political and anthropological projects: they were brought along on expeditions toWestern Canadaand were engaged to documentIndigenous peoples in Canadaby government agencies.

Canadian photography became more institutionalized in the 20th century. Railways including theCanadian Pacific Railwayheavily used photographs in their advertising campaigns. The Still Photography Division, a department of theNational Film Board of Canada,produced images for national and international distribution. Initially focussed on promoting a positive vision of the nation, by the 1960s the division transitioned todocumentary photographyattuned to individual photographers' artistic inclinations.

According to criticPenny Cousineau-Levine,contemporary photography in Canada de-emphasizes documenting reality; rather, it treats photographs as an invitation to consider the otherworldly.

19th century[edit]

In June 1839, theColonial Pearl,a weekly newspaper inHalifax, Nova Scotia,reported that one of its readers had created a "photogenic drawing," probably of samples of flora such as ferns or flowers, created without a camera by placing objects on "salted" or sensitized paper.[1]According to scholar Ralph Greenhill, this was the first such photograph produced in Canada.[2]In 1841 Tabot would call this thecalotypeprocess.

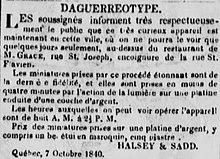

Canada was among the first countries to pioneer photography after thedaguerreotypewas released by its inventor, the FrenchmanLouis Daguerre,in 1839.[3]In late 1840, photographic "rooms" were being employed inMontrealandQuebec City,notably by two American itinerants, Halsey and Sadd.[4]Halsey and Sadd sold their prints for $5, including "a fine Morocco case".[5]Surviving examples of their work have been identified.[6] A Mrs John Fletcher, from Newburyport, was probably the first woman photographer in Canada when she and her husband (who was, in addition to his photographic pursuits, aphrenologist), established themselves briefly in Montreal in 1841; her advertisements stated that she could "execute Daguerreotype Miniatures in a style unsurpassed by an American or European artist".[7][8]In January, 1842William Valentineopened a studio in his home on Marchington's Lane in Halifax, establishing the first permanent studio in Canada.[9]A year later, Valentine and his partner, Nova Scotia-bornThomas Coffin Doanebriefly took rooms at the Golden Lion Inn inSt. John's, Newfoundland.[10] Doane would later become well known for his work in his adopted city of Montreal. The earliest daguerrotypist with close associations to Quebec was the Swiss-bornPierre-Gustave Joly.In 1839, he traveled to Greece and Egypt where he took some of the world's earliest daguerreotypes. The originals were lost but the copies published asengravingshave survived.[11]Eli J. Palmer(working in Toronto) was another early "daguerrian artist" operating in this early period.[12]The first photography-related patent in Canada went to L. A. Lemire in 1854 for abuffingprocess for daguerreotype plates.[13]

Early Canadianlandscape photographsare rare—except ofNiagara Falls,which attracted photographers from the daguerreotype era onward.[13]Portraitsprovided the economic basis for 19th-century commercial photography.[14]By the late 1850s, Canadian photographers had largely abandoned the daguerreotype in favour of theambrotype,[15]an application of thecollodion process.[10]

Scottish-bornWilliam Notmanwas Canada's best known portrait photographer in the second half of the 19th century.[16]Establishing in Montreal in the late 1850's, he was honoured as photographer to the Queen for his work during the1860 visitofEdward,then Prince of Wales, to Canada).[17]After Confederation he established additional studios in Ottawa and Toronto (1868),Halifax(1869) andSaint John(1872) before also venturing into the United States.[18]By the 1870s he was producing some 14,000 negatives a year. The Notman studios are remembered for their elaboratephotomontages,such as his coloured composite of the 1869 Skating Carnaval consisting of some 300 individual views, and for the indigenous scenes the studio created in its Montreal studio.[10]

Canadian photographers such asFrederick Dally,Edward Dosseter,andRichard Maynardwere commissioned by government agencies including the department of Indian affairs to conduct ethnographic portraiture ofIndigenous peoples in Canada.These images were sold and disseminated globally. Photographers of settlers, includingHannah Maynard's seriesGems of British Columbia,advertised the colonial frontier to prospective white newcomers.[19]

The Photographic Portfolio: A Monthly Review of Canadian Scenes and Scenerywas the first photography journal in Canada. It was published in Quebec City for two years, from 1858 to 1860, bySamuel McLaughlin(1824–1914).[20]

TheAssiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expeditionof 1857–1858, overseen byHenry Youle Hind,hiredHumphrey Lloyd Himeas the first official photographer of a colonial expedition.[21][22](Hime was a commercial photographer with the Toronto firm Armstrong, Beere & Hime; he left photography for a career in finance around 1860.[23]) Other colonial and anthropological expeditions in the 19th and early 20th centuries, such as theJesup North Pacific Expedition,also produced a large volume of photographs.[24]Likewise, the first photos of theCanadian Prairieswere taken on surveying trips and other officially sponsored explorations.[25]Several people associated with theHudson's Bay Companydocumented life attrading postsin photographs.[21]

Thedry platetechnique, which was easier than wet plate photography, became available in the 1880s. Professional photographers initially spurned the innovation, while amateurs quickly adopted it. Dry plate photography was used during theBritish Arctic Expedition(1875–1876).[26]

In the late 1800s, with the advent ofhalftoneprinting, photography became more common inadvertisingand other media.Canadian Illustrated News,first published on 30 October 1869, made pioneering use of halftone photographic prints.[27]This technological development coincided with a movement to develop the Prairies into "the granary of the British Empire"; images promoting settlement in Western Canada proliferated.[28]TheCanadian Pacific Railway(CPR) avidly used photographs in its offices abroad to promoteimmigration to Canada.[29]The CPR andCanadian National Railway,which also maintained a photography collection, provided pictures free of charge to writers on Canada.[30]

Photographers and studios including William Notman,Alexander Henderson,and O. B. Buell were all engaged as part of campaigns by the federal government, CPR, and others to encourage settlement.[31]Local professional and amateur photographers in the Canadian West also documented the region during this period, often focussing on farm equipment.[32]In 1888 theToronto Camera Clubwas founded (as the Toronto Amateur Photographic Association).[33]

-

Olympian Zeus Temple and Acropolis, Athens, 1839, engraving of Pierre-Gustave Joly's daguerreotype

-

Lloyd Hime's photograph of McDermot's store, Fort Garry, Manitoba, 1858

-

Notman's Montreal Skating Carnaval, colored composite 1870

-

Last Spike at Craigellachie,British Columbia, 1885

20th century[edit]

Concerns about the absence of a specific Canadian mode of photography were aired in the early 20th century, both by Canadians includingHarold Mortimer-Lamb,who lamented that the Canadian natural world was not sufficiently represented, and at least one British critic who remarked that there was no evidence of a "Canadian spirit" in then-contemporary photographic output.[34]

Around the turn of the 20th century, developments inprintingtechnology made it possible for Canadian amateurs and professionals to produce their own photographicpostcards.[35]In 1913, 60million postcards were sent in Canada.[36]

InTorontoaround the turn of the 20th century, newspapers and other periodicals documentedthe Ward,a poor and largely immigrant neighbourhood, in photographs. Copioushalftoneprints in papers includingThe Toronto WorldandThe Globe,[37]many byWilliam James,[38]illustrated articles designed to shock, entertain, and attract readers with the lives of Ward residents.[39]

The CPR, as part of an advertising campaign in the 1920s and 1930s, commissioned photographers includingJohn Vanderpant,whom scholar Jill Delaney described as the "leadingpictorialistphotographer in Canada ",[40]to documentWestern Canada,particularly theRockies.[41]The campaign aimed to associate Canada as a nation with its natural environment—and both with the CPR.[42]The CPR had used photography to memorialize and promote its operations at least since 1885, when thelast spikewas driven in;[42]Alexander Ross of Calgary took the iconic photograph, which was widely distributed.[43]

Beginning in the 1940s, the Canadian federal government had a photography department. On 8 August 1941, the Still Photography Division, sometimes simply called Photo Services, was transferred to theNational Film Board of Canadapursuant to anorder in council.The division employed photographers, photo editors, and others to create photographs in service of "national unity".[44]During the Second World War, the division focussed on documenting thehome front.[45]Staff also produced photographs for other federal agencies and provided content for publications not affiliated with the government.[46]Scholar Carol Payne argues that a major role of the division during the war was to producepropaganda.[47]

After the war, the Still Photography Division's budget was cut substantially, even as the National Film Board tried to maintain its status as the federal government's only official photography agency.[48]It continued to promote a vision of Canadian nationhood in peacetime through the 1950s.[49]One distinctive channel for the division's efforts was thephoto story,often distributed as a newspaper supplement.[50]Photo stories were uncritically positive; Payne calls them "jingoistic".[51]WhenLorraine Monktook over as head of the Still Photography Division in 1960, she turned the division away from the photo story model in favour ofdocumentary photographymore attuned to the sensibilities of individual photographers.[52]This was part of a broader turn towardsmodernismin Canadian thinking about photography: it was viewed as an art form, not solely as a means of reporting on reality.[53]The division's final photo story was published in April 1971.[54]Later that year, the division ceased to be the federal government's sole photography agency when, as part of a broader redistribution of responsibilities and personnel, some of the division's photographers were sent to Information Canada (another federal department).[55]

As of the early 1940s,Yousuf Karshwas "one of Canada's pre-eminent portrait photographers".[56]

The Commercial and Press Photographers Association of Canada, which changed its name toProfessional Photographers of Canada(PPC) in 1962, was founded in 1946. Aprofessional associationforphotojournalists,PPC aimed to create "a strong national identity for all those involved in the photographic industry".[57]

Critic Serge Jongué argues that photography inQuebechad shifted from a documentary focus during the 1970s to an emphasis onexperimentalismas of the early 1990s. He links this development to rapid cultural changes in the province during the latter half of the 20th century, including theQuiet Revolution.[58]He identifiesGabor SzilasiandPierre Gaudardas two key figures in Quebec photography of the late 20th century.[59]

Contemporary[edit]

Penny Cousineau-Levinesuggests thatdeathis a predominant theme in contemporary Canadian photography.[60]She argues, against theories of photography defended bySusan SontaginOn PhotographyandRoland BarthesinCamera Lucida,that Canadian photographers use a medium uniquely capable ofmimesisso as to distance themselves from the real: "[t]hesine qua nonof photography, its unique capacity for verisimilitude, is the very trait that many Canadian photographers seem distinctly ill at ease with. "[61]According to Cousineau-Levine, Canadianstreet photographyis more often about otherworldly matters than a comment on the worldly events it nominally depicts.[61]She identifies a set of portraits taken byKaren Smileyin 1976, and the work ofAnne-Marie Zeppetelli,as exemplars of Canadian photographers' use of this realist medium to explore themes beyond the everyday.[62]

Comparing Canadian portraits of working people byCal Baileywith their American counterparts byIrving PennandRichard Avedon,Cousineau-Levine suggests that the Canadian portraits show their subjects as "uprooted" from their surroundings—by contrast with the American portraits, which, according to Cousineau-Levine, do not depict people ill at ease in the frame.[63]This tendency to dislocate the photographic subject from its background persists, says Cousineau-Levine, in Canadian architecture photography by artists includingOrest Semchishen.[64]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^"Photogenic Drawings".Salt Prints at Harvard.Harvard University.Retrieved6 July2024.

- ^Greenhill 1965,p. 18.

- ^Stauble, Katherine (10 September 2015)."Early Canadian Daguerreotypes: Brilliant Jewels".National Gallery of Canada.Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2021.Retrieved28 October2021.

- ^Palmquist & Kailbourn 2005,p. 298.

- ^Greenhill 1965,p. 22.

- ^Garrett, Graham (May–June 1996). "Photography in Canada 1839-1841 (Part Two)".Photographic Canadiana.22(1): 4.

- ^"Fletcher, Mrs. John".Canadian Women Artists History Initiative. 15 December 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 13 October 2020.Retrieved28 October2021.

- ^Greenhill 1965,pp. 23–24.

- ^Burant, Jim (Spring 1977)."Pre-Confederation Photography in Halifax, Nova Scotia".The Journal of Canadian Art History.4(1): 27.Retrieved6 July2024.

- ^abcTweedie, Katherine;Cousineau, Penny(20 April 2006)."Photography".The Canadian Encyclopedia.Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2021.Retrieved28 October2021.

- ^Nadeau, Jean-François (30 November 2013)."Les origines de la photographie au Québec".Le Devoir(in French).Archivedfrom the original on 25 October 2021.Retrieved28 October2021.

- ^Greenhill 1965,pp. 24–25.

- ^abGreenhill 1965,p. 25.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,p. 25.

- ^Greenhill 1965,p. 30.

- ^Cousineau-Levine 2003,p. 30.

- ^Greenhill 1965,p. 39.

- ^Hall, Roger, Gordon Dodds, Stanley Triggs (1883).The World of William Notman(1 ed.). Boston: David R. Godine. pp. 22–35, 38–60.ISBN0771037732.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Kunard & Payne 2011,pp. 27–29.

- ^Greenhill 1965,p. 37.

- ^abKunard & Payne 2011,p. 72.

- ^Greenhill 1965,p. 50.

- ^Greenhill 1965,p. 36.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,p. 73.

- ^Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography 1992,p. 14.

- ^Greenhill 1965,pp. 58–59.

- ^Greenhill 1965,p. 65.

- ^Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography 1992,pp. 15–16.

- ^Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography 1992,p. 16.

- ^Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography 1992,p. 17.

- ^Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography 1992,p. 18.

- ^Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography 1992,pp. 25–26.

- ^Kuitenbrouwer, Peter (25 January 2015)."The Toronto Camera Club, founded the same year as the first roll of film was introduced, celebrates 125 years".National Post.Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,p. 59.

- ^Hatfield 2018,pp. 4–5.

- ^Hatfield 2018,p. 10.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,pp. 115–116.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,p. 114.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,pp. 111–112.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,pp. 57.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,pp. 60–62.

- ^abKunard & Payne 2011,p. 61.

- ^Francis, Daniel (5 February 2019)."The Last Spike".The Canadian Encyclopedia.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2021.Retrieved27 October2021.

- ^Payne 2013,pp. 20–21.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 23.

- ^Payne 2013,pp. 25–26.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 26.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 31.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 32.

- ^Payne 2013,pp. 37–38.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 43.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 45.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 46.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 51.

- ^Payne 2013,p. 52.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,p. 121.

- ^Kunard & Payne 2011,p. 154.

- ^Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography 1992,pp. 38–39.

- ^Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography 1992,pp. 39–40.

- ^Cousineau-Levine 2003,p. 18.

- ^abCousineau-Levine 2003,p. 24.

- ^Cousineau-Levine 2003,pp. 26–27.

- ^Cousineau-Levine 2003,pp. 35–36.

- ^Cousineau-Levine 2003,pp. 37.

Sources[edit]

- 13 Essays on Photography.Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography.1992.ISBN9780888845573.OCLC1145816193.

- Cousineau-Levine, Penny(2003).Faking Death: Canadian Art Photography and the Canadian Imagination.McGill–Queen's University Press.ISBN978-0-7735-7095-5.OCLC180704373.

- Greenhill, Ralph (1965).Early Photography in Canada.Oxford University Press.OCLC299937776.

- Hatfield, Philip J. (18 June 2018).Canada in the Frame: Copyright, Collections and the Image of Canada, 1895–1924.UCL Press.doi:10.2307/j.ctv3hvc7m.ISBN978-1-78735-299-5.JSTORj.ctv3hvc7m.OCLC1045427072.

- Kunard, Andrea; Payne, Carol, eds. (2011).The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada.McGill–Queen's University Press.ISBN978-0-7735-8572-0.OCLC806255104.

- Palmquist, Peter E.; Kailbourn, Thomas R. (2005).Pioneer Photographers from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide: A Biographical Dictionary, 1839–1865.Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0-8047-4057-9.

- Payne, Carol (2013).The Official Picture: The National Film Board of Canada's Still Photography Division and the Image of Canada, 1941–1971.McGill–Queen's University Press.ISBN978-0-7735-8894-3.OCLC1037916154.

Further reading[edit]

- The Banff Purchase: An Exhibition of Photography in Canada.Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity;Wiley.1979.ISBN0-471-99829-X.OCLC6981452.

- Close, Susan (2007).Framing Identity: Social Practices of Photography in Canada, 1880–1920.Arbeiter Ring Publishing.ISBN978-1-894037-29-7.OCLC137329800.

- Contemporary Canadian Photography: From the Collection of the National Film Board.National Film Board of Canada;Hurtig Publishers.1984.ISBN0-88830-264-9.OCLC12134746.

- Kunard, Andrea (2017).Photography in Canada 1960–2000.Canadian Photography Institute,National Gallery of Canada.ISBN978-0-88884-948-9.OCLC973151202.

- Pedersen, Diana; Phemister, Martha (1985)."Women and Photography in Ontario, 1839–1929: A Case Study of the Interaction of Gender and Technology".Scientia Canadensis: Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine.9(1): 27–52.doi:10.7202/800204ar.ISSN0829-2507.

- Silversides, Brock V. (1999).Looking West: Photographing the Canadian Prairies, 1858–1957.Fifth House Publishers.ISBN1-894004-09-4.OCLC45087565.