Plant physiology

Plant physiologyis a subdiscipline ofbotanyconcerned with the functioning, orphysiology,ofplants.[1]

Plant physiologists study fundamental processes of plants, such asphotosynthesis,respiration,plant nutrition,plant hormonefunctions,tropisms,nastic movements,photoperiodism,photomorphogenesis,circadian rhythms,environmental stressphysiology, seedgermination,dormancyandstomatafunction andtranspiration.Plant physiology interacts with the fields ofplant morphology(structure of plants), plantecology(interactions with the environment),phytochemistry(biochemistryof plants),cell biology,genetics, biophysics andmolecular biology.

Aims[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(January 2024) |

The field of plant physiology includes the study of all the internal activities of plants—those chemical and physical processes associated withlifeas they occur in plants. This includes study at many levels of scale of size and time. At the smallest scale aremolecularinteractions ofphotosynthesisand internaldiffusionof water, minerals, and nutrients. At the largest scale are the processes of plantdevelopment,seasonality,dormancy,andreproductivecontrol. Major subdisciplines of plant physiology includephytochemistry(the study of thebiochemistryof plants) andphytopathology(the study ofdiseasein plants). The scope of plant physiology as a discipline may be divided into several major areas of research.

First, the study ofphytochemistry(plant chemistry) is included within the domain of plant physiology. To function and survive, plants produce a wide array of chemical compounds not found in other organisms.Photosynthesisrequires a large array ofpigments,enzymes,and other compounds to function. Because they cannot move, plants must also defend themselves chemically fromherbivores,pathogensand competition from other plants. They do this by producingtoxinsand foul-tasting or smelling chemicals. Other compounds defend plants against disease, permit survival during drought, and prepare plants for dormancy, while other compounds are used to attractpollinatorsor herbivores to spread ripe seeds.

Secondly, plant physiology includes the study of biological and chemical processes of individual plantcells.Plant cells have a number of features that distinguish them from cells ofanimals,and which lead to major differences in the way that plant life behaves and responds differently from animal life. For example, plant cells have acell wallwhich maintains the shape of plant cells. Plant cells also containchlorophyll,a chemical compound that interacts withlightin a way that enables plants to manufacture their own nutrients rather than consuming other living things as animals do.

Thirdly, plant physiology deals with interactions between cells,tissues,and organs within a plant. Different cells and tissues are physically and chemically specialized to perform different functions.Rootsandrhizoidsfunction to anchor the plant and acquire minerals in the soil.Leavescatch light in order to manufacture nutrients. For both of these organs to remain living, minerals that the roots acquire must be transported to the leaves, and the nutrients manufactured in the leaves must be transported to the roots. Plants have developed a number of ways to achieve this transport, such asvascular tissue,and the functioning of the various modes of transport is studied by plant physiologists.

Fourthly, plant physiologists study the ways that plants control or regulate internal functions. Like animals, plants produce chemicals calledhormoneswhich are produced in one part of the plant to signal cells in another part of the plant to respond. Manyflowering plantsbloom at the appropriate time because of light-sensitive compounds that respond to the length of the night, a phenomenon known asphotoperiodism.Theripeningoffruitand loss of leaves in the winter are controlled in part by the production of the gasethyleneby the plant.

Finally, plant physiology includes the study of plant response to environmental conditions and their variation, a field known asenvironmental physiology.Stress from water loss, changes in air chemistry, or crowding by other plants can lead to changes in the way a plant functions. These changes may be affected by genetic, chemical, and physical factors.

Biochemistry of plants[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(January 2024) |

Thechemical elementsof which plants are constructed—principallycarbon,oxygen,hydrogen,nitrogen,phosphorus,sulfur,etc.—are the same as for all other life forms: animals, fungi,bacteriaand evenviruses.Only the details of their individual molecular structures vary.

Despite this underlying similarity, plants produce a vast array of chemical compounds with unique properties which they use to cope with their environment.Pigmentsare used by plants to absorb or detect light, and are extracted by humans for use indyes.Other plant products may be used for the manufacture of commercially importantrubberorbiofuel.Perhaps the most celebrated compounds from plants are those withpharmacologicalactivity, such assalicylic acidfrom whichaspirinis made,morphine,anddigoxin.Drug companiesspend billions of dollars each year researching plant compounds for potential medicinal benefits.

Constituent elements[edit]

Plants require somenutrients,such ascarbonandnitrogen,in large quantities to survive. Some nutrients are termedmacronutrients,where the prefixmacro-(large) refers to the quantity needed, not the size of the nutrient particles themselves. Other nutrients, calledmicronutrients,are required only in trace amounts for plants to remain healthy. Such micronutrients are usually absorbed asionsdissolved in water taken from the soil, thoughcarnivorous plantsacquire some of their micronutrients from captured prey.

The following tables listelementnutrients essential to plants. Uses within plants are generalized.

| Element | Form of uptake | Notes |

| Nitrogen | NO3−,NH4+ | Nucleic acids, proteins, hormones, etc. |

| Oxygen | O2,H2O | Cellulose,starch,other organic compounds |

| Carbon | CO2 | Cellulose, starch, other organic compounds |

| Hydrogen | H2O | Cellulose, starch, other organic compounds |

| Potassium | K+ | Cofactor in protein synthesis, water balance, etc. |

| Calcium | Ca2+ | Membrane synthesis and stabilization |

| Magnesium | Mg2+ | Element essential for chlorophyll |

| Phosphorus | H2PO4− | Nucleic acids, phospholipids, ATP |

| Sulphur | SO42− | Constituent of proteins |

| Element | Form of uptake | Notes |

| Chlorine | Cl− | Photosystem II and stomata function |

| Iron | Fe2+,Fe3+ | Chlorophyll formation and nitrogen fixation |

| Boron | HBO3 | Crosslinking pectin |

| Manganese | Mn2+ | Activity of some enzymes and photosystem II |

| Zinc | Zn2+ | Involved in the synthesis of enzymes and chlorophyll |

| Copper | Cu+ | Enzymes for lignin synthesis |

| Molybdenum | MoO42− | Nitrogen fixation, reduction of nitrates |

| Nickel | Ni2+ | Enzymatic cofactor in the metabolism of nitrogen compounds |

Pigments[edit]

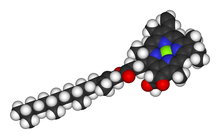

Among the most important molecules for plant function are thepigments.Plant pigments include a variety of different kinds of molecules, includingporphyrins,carotenoids,andanthocyanins.Allbiological pigmentsselectively absorb certainwavelengthsoflightwhilereflectingothers. The light that is absorbed may be used by the plant to powerchemical reactions,while the reflected wavelengths of light determine thecolorthe pigment appears to the eye.

Chlorophyllis the primary pigment in plants; it is aporphyrinthat absorbs red and blue wavelengths of light while reflectinggreen.It is the presence and relative abundance of chlorophyll that gives plants their green color. All land plants andgreen algaepossess two forms of this pigment: chlorophyllaand chlorophyllb.Kelps,diatoms,and other photosyntheticheterokontscontain chlorophyllcinstead ofb,red algaepossess chlorophylla.All chlorophylls serve as the primary means plants use to intercept light to fuelphotosynthesis.

Carotenoidsare red, orange, or yellowtetraterpenoids.They function as accessory pigments in plants, helping to fuelphotosynthesisby gathering wavelengths of light not readily absorbed by chlorophyll. The most familiar carotenoids arecarotene(an orange pigment found incarrots),lutein(a yellow pigment found in fruits and vegetables), andlycopene(the red pigment responsible for the color oftomatoes). Carotenoids have been shown to act asantioxidantsand to promote healthyeyesightin humans.

Anthocyanins(literally "flower blue" ) arewater-solubleflavonoidpigmentsthat appear red to blue, according topH.They occur in alltissuesof higher plants, providing color inleaves,stems,roots,flowers,andfruits,though not always in sufficient quantities to be noticeable. Anthocyanins are most visible in thepetalsof flowers, where they may make up as much as 30% of the dry weight of the tissue.[2]They are also responsible for the purple color seen on the underside of tropical shade plants such asTradescantia zebrina.In these plants, the anthocyanin catches light that has passed through the leaf and reflects it back towards regions bearing chlorophyll, in order to maximize the use of available light

Betalainsare red or yellow pigments. Like anthocyanins they are water-soluble, but unlike anthocyanins they areindole-derived compounds synthesized fromtyrosine.This class of pigments is found only in theCaryophyllales(includingcactusandamaranth), and never co-occur in plants with anthocyanins. Betalains are responsible for the deep red color ofbeets,and are used commercially as food-coloring agents. Plant physiologists are uncertain of the function that betalains have in plants which possess them, but there is some preliminary evidence that they may have fungicidal properties.[3]

Signals and regulators[edit]

Plants produce hormones and other growth regulators which act to signal a physiological response in their tissues. They also produce compounds such asphytochromethat are sensitive to light and which serve to trigger growth or development in response to environmental signals.

Plant hormones[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(January 2024) |

Plant hormones,known as plant growth regulators (PGRs) or phytohormones, are chemicals that regulate a plant's growth. According to a standard animal definition,hormonesare signal molecules produced at specific locations, that occur in very low concentrations, and cause altered processes in target cells at other locations. Unlike animals, plants lack specific hormone-producing tissues or organs. Plant hormones are often not transported to other parts of the plant and production is not limited to specific locations.

Plant hormones arechemicalsthat in small amounts promote and influence thegrowth,developmentanddifferentiationof cells and tissues. Hormones are vital to plant growth; affecting processes in plants from flowering toseeddevelopment,dormancy,andgermination.They regulate which tissues grow upwards and which grow downwards, leaf formation and stem growth, fruit development and ripening, as well as leafabscissionand even plant death.

The most important plant hormones areabscissic acid(ABA),auxins,ethylene,gibberellins,andcytokinins,though there are many other substances that serve to regulate plant physiology.

Photomorphogenesis[edit]

While most people know thatlightis important for photosynthesis in plants, few realize that plant sensitivity to light plays a role in the control of plant structural development (morphogenesis). The use of light to control structural development is calledphotomorphogenesis,and is dependent upon the presence of specializedphotoreceptors,which are chemicalpigmentscapable of absorbing specificwavelengthsof light.

Plants use four kinds of photoreceptors:[1]phytochrome,cryptochrome,aUV-Bphotoreceptor, andprotochlorophyllidea.The first two of these, phytochrome and cryptochrome, arephotoreceptor proteins,complex molecular structures formed by joining aproteinwith a light-sensitive pigment. Cryptochrome is also known as the UV-A photoreceptor, because it absorbsultravioletlight in the long wave "A" region. The UV-B receptor is one or more compounds not yet identified with certainty, though some evidence suggestscaroteneorriboflavinas candidates.[4]Protochlorophyllidea,as its name suggests, is a chemical precursor ofchlorophyll.

The most studied of the photoreceptors in plants isphytochrome.It is sensitive to light in theredandfar-redregion of thevisible spectrum.Many flowering plants use it to regulate the time offloweringbased on the length of day and night (photoperiodism) and to set circadian rhythms. It also regulates other responses including the germination of seeds, elongation of seedlings, the size, shape and number of leaves, the synthesis of chlorophyll, and the straightening of theepicotylorhypocotylhook ofdicotseedlings.

Photoperiodism[edit]

Manyflowering plantsuse the pigment phytochrome to sense seasonal changes indaylength, which they take as signals to flower. This sensitivity to day length is termedphotoperiodism.Broadly speaking, flowering plants can be classified as long day plants, short day plants, or day neutral plants, depending on their particular response to changes in day length. Long day plants require a certain minimum length of daylight to start flowering, so these plants flower in the spring or summer. Conversely, short day plants flower when the length of daylight falls below a certain critical level. Day neutral plants do not initiate flowering based on photoperiodism, though some may use temperature sensitivity (vernalization) instead.

Although a short day plant cannot flower during the long days of summer, it is not actually the period of light exposure that limits flowering. Rather, a short day plant requires a minimal length of uninterrupted darkness in each 24-hour period (a short daylength) before floral development can begin. It has been determined experimentally that a short day plant (long night) does not flower if a flash of phytochrome activating light is used on the plant during the night.

Plants make use of the phytochrome system to sense day length or photoperiod. This fact is utilized byfloristsandgreenhousegardeners to control and even induce flowering out of season, such as thepoinsettia(Euphorbia pulcherrima).

Environmental physiology[edit]

Paradoxically, the subdiscipline of environmental physiology is on the one hand a recent field of study in plant ecology and on the other hand one of the oldest.[1]Environmental physiology is the preferred name of the subdiscipline among plant physiologists, but it goes by a number of other names in the applied sciences. It is roughly synonymous withecophysiology,crop ecology,horticultureandagronomy.The particular name applied to the subdiscipline is specific to the viewpoint and goals of research. Whatever name is applied, it deals with the ways in which plants respond to their environment and so overlaps with the field ofecology.

Environmental physiologists examine plant response to physical factors such asradiation(includinglightandultravioletradiation),temperature,fire,andwind.Of particular importance arewaterrelations (which can be measured with thePressure bomb) and the stress ofdroughtorinundation,exchange of gases with theatmosphere,as well as the cycling of nutrients such asnitrogenandcarbon.

Environmental physiologists also examine plant response to biological factors. This includes not only negative interactions, such ascompetition,herbivory,diseaseandparasitism,but also positive interactions, such asmutualismandpollination.

While plants, as living beings, can perceive and communicate physical stimuli and damage, they do not feelpainas members of theanimal kingdomdo simply because of the lack of anypain receptors,nerves,or abrain,[6]and, by extension, lack ofconsciousness.[7]Many plants are known to perceive and respond to mechanical stimuli at a cellular level, and some plants such as thevenus flytraportouch-me-not,are known for their "obvious sensory abilities".[6]Nevertheless, the plant kingdom as a whole do not feel pain notwithstanding their abilities to respond to sunlight, gravity, wind, and any external stimuli such as insect bites, since they lack any nervous system. The primary reason for this is that, unlike the members of theanimal kingdomwhose evolutionary successes and failures are shaped by suffering, the evolution of plants are simply shaped by life and death.[6]

Tropisms and nastic movements[edit]

Plants may respond both to directional and non-directionalstimuli.A response to a directional stimulus, such asgravityorsun light,is called a tropism. A response to a nondirectional stimulus, such astemperatureorhumidity,is a nastic movement.

Tropismsin plants are the result of differentialcellgrowth, in which the cells on one side of the plant elongates more than those on the other side, causing the part to bend toward the side with less growth. Among the common tropisms seen in plants isphototropism,the bending of the plant toward a source of light. Phototropism allows the plant to maximize light exposure in plants which require additional light for photosynthesis, or to minimize it in plants subjected to intense light and heat.Geotropismallows the roots of a plant to determine the direction of gravity and grow downwards. Tropisms generally result from an interaction between the environment and production of one or more plant hormones.

Nastic movementsresults from differential cell growth (e.g. epinasty and hiponasty), or from changes inturgor pressurewithin plant tissues (e.g.,nyctinasty), which may occur rapidly. A familiar example isthigmonasty(response to touch) in theVenus fly trap,acarnivorous plant.The traps consist of modified leaf blades which bear sensitive trigger hairs. When the hairs are touched by an insect or other animal, the leaf folds shut. This mechanism allows the plant to trap and digest small insects for additional nutrients. Although the trap is rapidly shut by changes in internal cell pressures, the leaf must grow slowly to reset for a second opportunity to trap insects.[8]

Plant disease[edit]

Economically, one of the most important areas of research in environmental physiology is that ofphytopathology,the study ofdiseasesin plants and the manner in which plants resist or cope with infection. Plant are susceptible to the same kinds of disease organisms as animals, includingviruses,bacteria,andfungi,as well as physical invasion byinsectsandroundworms.

Because the biology of plants differs with animals, their symptoms and responses are quite different. In some cases, a plant can simply shed infected leaves or flowers to prevent the spread of disease, in a process called abscission. Most animals do not have this option as a means of controlling disease. Plant diseases organisms themselves also differ from those causing disease in animals because plants cannot usually spread infection through casual physical contact. Plantpathogenstend to spread viasporesor are carried by animalvectors.

One of the most important advances in the control of plant disease was the discovery ofBordeaux mixturein the nineteenth century. The mixture is the first knownfungicideand is a combination ofcopper sulfateandlime.Application of the mixture served to inhibit the growth ofdowny mildewthat threatened to seriously damage theFrenchwineindustry.[9]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Francis Baconpublished one of the first plant physiology experiments in 1627 in the book,Sylva Sylvarum.Bacon grew several terrestrial plants, including a rose, in water and concluded that soil was only needed to keep the plant upright.Jan Baptist van Helmontpublished what is considered the first quantitative experiment in plant physiology in 1648. He grew a willow tree for five years in a pot containing 200 pounds of oven-dry soil. The soil lost just two ounces of dry weight and van Helmont concluded that plants get all their weight from water, not soil. In 1699,John Woodwardpublished experiments on growth ofspearmintin different sources of water. He found that plants grew much better in water with soil added than in distilled water.

Stephen Halesis considered the Father of Plant Physiology for the many experiments in the 1727 book,Vegetable Staticks;[10]thoughJulius von Sachsunified the pieces of plant physiology and put them together as a discipline. HisLehrbuch der Botanikwas the plant physiology bible of its time.[11]

Researchers discovered in the 1800s that plants absorb essential mineral nutrients as inorganic ions in water. In natural conditions, soil acts as a mineral nutrient reservoir but the soil itself is not essential to plant growth. When the mineral nutrients in the soil are dissolved in water, plant roots absorb nutrients readily, soil is no longer required for the plant to thrive. This observation is the basis forhydroponics,the growing of plants in a water solution rather than soil, which has become a standard technique in biological research, teaching lab exercises, crop production and as a hobby.

Economic applications[edit]

Food production[edit]

Inhorticultureandagriculturealong withfood science,plant physiology is an important topic relating tofruits,vegetables,and other consumable parts of plants. Topics studied include:climaticrequirements, fruit drop, nutrition,ripening,fruit set. The production of food crops also hinges on the study of plant physiology covering such topics as optimal planting and harvesting times and post harvest storage of plant products for human consumption and the production of secondary products like drugs and cosmetics.

Crop physiology steps back and looks at a field of plants as a whole, rather than looking at each plant individually. Crop physiology looks at how plants respond to each other and how to maximize results like food production through determining things like optimalplanting density.

See also[edit]

- Biomechanics

- Hyperaccumulator

- Phytochemistry

- Plant anatomy

- Plant morphology

- Plant secondary metabolism

- Branches of botany

References[edit]

- ^abcFrank B. Salisbury; Cleon W. Ross (1992).Plant physiology.Brooks/Cole Pub Co.ISBN0-534-15162-0.

- ^Trevor Robinson (1963).The organic constituents of higher plants: their chemistry and interrelationships.Cordus Press. p. 183.

- ^Kimler, L. M. (1975). "Betanin, the red beet pigment, as an antifungal agent".Botanical Society of America, Abstracts of Papers.36.

- ^Fosket, Donald E. (1994).Plant Growth and Development: A Molecular Approach.San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 498–509.ISBN0-12-262430-0.

- ^"plantphys.net".Archived fromthe originalon 2006-05-12.Retrieved2007-09-22.

- ^abcPetruzzello, Melissa (2016)."Do Plants Feel Pain?".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved8 January2023.

Given that plants do not have pain receptors, nerves, or a brain, they do not feel pain as we members of the animal kingdom understand it. Uprooting a carrot or trimming a hedge is not a form of botanical torture, and you can bite into that apple without worry.

- ^Draguhn, Andreas; Mallatt, Jon M.; Robinson, David G. (2021)."Anesthetics and plants: no pain, no brain, and therefore no consciousness".Protoplasma.258(2). Springer: 239–248.doi:10.1007/s00709-020-01550-9.PMC7907021.PMID32880005.32880005.

- ^Adrian Charles Slack; Jane Gate (1980).Carnivorous Plants.Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 160.ISBN978-0-262-19186-9.

- ^Kingsley Rowland Stern; Shelley Jansky (1991).Introductory Plant Biology.WCB/McGraw-Hill. p. 309.ISBN978-0-697-09948-8.

- ^Hales, Stephen. 1727.Vegetable Statickshttp:// illustratedgarden.org/mobot/rarebooks/title.asp?relation=QK711H341727

- ^Duane Isely (1994).101 Botanists.Iowa State Press. pp.216–219.ISBN978-0-8138-2498-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Lambers, H. (1998).Plant physiological ecology.New York: Springer-Verlag.ISBN0-387-98326-0.

- Larcher, W. (2001).Physiological plant ecology(4th ed.). Springer.ISBN3-540-43516-6.

- Frank B. Salisbury; Cleon W. Ross (1992).Plant physiology.Brooks/Cole Pub Co.ISBN0-534-15162-0.

- Lincoln Taiz, Eduardo Zeiger, Ian Max Møller, Angus Murphy:Fundamentals of Plant Physiology.Sinauer, 2018.