Poland

Republic of Poland Rzeczpospolita Polska(Polish) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem:"Mazurek Dąbrowskiego"[a] ( "Poland Is Not Yet Lost" ) | |

Location of Poland (dark green) – inEurope(green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Warsaw 52°13′N21°02′E/ 52.217°N 21.033°E |

| Official language | Polish[1] |

| Ethnic groups (2021)[2] |

|

| Religion (2021[3]) |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic[4][5][6][7] |

| Andrzej Duda | |

| Donald Tusk | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Sejm | |

| Formation | |

| c.960 | |

| 14 April 966 | |

| 18 April 1025 | |

| 1 July 1569 | |

| 11 November 1918 | |

| 17 September 1939 | |

| 22 July 1944 | |

| 31 December 1989[9] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 312,696 km2(120,733 sq mi)[11][12](69th) |

• Water (%) | 1.48 (2015)[10] |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | |

• Density | 122/km2(316.0/sq mi) (75th) |

| GDP(PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP(nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini(2022) | low inequality |

| HDI(2022) | very high(36th) |

| Currency | Złoty(PLN) |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (CE) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +48 |

| ISO 3166 code | PL |

| Internet TLD | .pl[a] |

| |

Poland,[e]officially theRepublic of Poland,[f]is a country inCentral Europe.It extends from theBaltic Seain the north to theSudetesandCarpathian Mountainsin the south, bordered byLithuaniaandRussia[g]to the northeast,BelarusandUkraineto the east,Slovakiaand theCzech Republicto the south, andGermanyto the west. The territory is characterised by a varied landscape, diverse ecosystems, andtemperate transitionalclimate. Poland is composed ofsixteen voivodeshipsand is the fifth most populousmember state of the European Union(EU), with over 38 million people, and thefifth largest EU countryby land area, covering a combined area of 312,696 km2(120,733 sq mi). The capital andlargest cityisWarsaw;other major cities includeKraków,Wrocław,Łódź,Poznań,andGdańsk.

Prehistoric human activity on Polish soildates to theLower Paleolithic,with continuous settlement since the end of theLast Glacial Period.Culturally diverse throughoutlate antiquity,in theearly medieval periodthe region became inhabited by theWest SlavictribalPolans,who gavePoland its name.The process of establishing statehood coincided with the conversion of apagan ruler of the Polansto Christianity, under the auspices of theRoman Catholic Churchin 966. TheKingdom of Polandemerged in 1025, and in 1569 cemented its long-standingassociation with Lithuania,thus forming thePolish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.At the time, the Commonwealth was one of thegreat powersof Europe, with anelective monarchyand auniquely liberalpolitical system, which adoptedEurope's first modern constitutionin 1791.

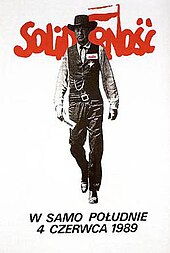

With the passing of the prosperousPolish Golden Age,the country waspartitioned by neighbouring statesat the end of the 18th century. Poland regained itsindependenceat the end ofWorld War Iin 1918 with the creation of theSecond Polish Republic,which emergedvictoriousinvarious conflictsof theinterbellumperiod. In September 1939, theinvasion of PolandbyGermanyand theSoviet Unionmarked the beginning ofWorld War II,which resulted inthe Holocaustand millions ofPolish casualties.Forced into theEastern Blocin the globalCold War,thePolish People's Republicwas a founding signatory of theWarsaw Pact.Through theemergenceand contributions of theSolidarity movement,thecommunist governmentwasdissolvedand Poland re-established itself as ademocratic statein 1989, as thefirstof its neighbors, initiating thefall of the Iron Curtain.

Poland is aparliamentary republicwith itsbicameral legislaturecomprising theSejmand theSenate.Considered amiddle power,it is adeveloped marketandhigh-income economythat is thesixth largestin theEUby nominalGDPand thefifth largest by GDP (PPP).Poland enjoys avery high standard of living,safety, andeconomic freedom,as well as freeuniversity educationanduniversal health care.The country has 17UNESCOWorld Heritage Sites,15 of which are cultural. Poland is a founding member state of the United Nations and a member of theWorld Trade Organization,OECD,NATO,and theEuropean Union(including theSchengen Area).

Etymology

The nativePolishname for Poland isPolska.[17]The name is derived from thePolans,aWest Slavictribe who inhabited theWarta Riverbasin of present-dayGreater Polandregion (6th–8th century CE).[18]The tribe's name stems from theProto-Slavicnounpolemeaning field, which in-itself originates from theProto-Indo-Europeanword*pleh₂-indicating flatland.[19]The etymology alludes to thetopographyof the region and the flat landscape of Greater Poland.[20][21]During theMiddle Ages,theLatinformPoloniawas widely used throughout Europe.[22]

The country's alternative archaic name isLechiaand its root syllable remains in official use in several languages, notablyHungarian,Lithuanian,andPersian.[23]Theexonympossibly derives from eitherLech,a legendary ruler of theLechites,or from theLendians,a West Slavic tribe that dwelt on the south-easternmost edge ofLesser Poland.[24][25]The origin of the tribe's name lies in theOld Polishwordlęda(plain).[26]Initially, both namesLechiaandPoloniawere used interchangeably when referring to Poland by chroniclers during theMiddle Ages.[27]

History

Prehistory and protohistory

The firstStone Agearchaic humans andHomo erectusspecies settled what was to become Poland approximately 500,000 years ago, though the ensuing hostile climate prevented early humans from founding more permanent encampments.[28]The arrival ofHomo sapiensandanatomically modern humanscoincided with the climatic discontinuity at the end of theLast Glacial Period(Northern Polish glaciation10,000 BC), when Poland became habitable.[29]Neolithicexcavations indicated broad-ranging development in that era; the earliest evidence of European cheesemaking (5500 BC) was discovered in PolishKuyavia,[30]and theBronocice potis incised with the earliest known depiction of what may be a wheeled vehicle (3400 BC).[31]

The period spanning theBronze Ageand theEarly Iron Age(1300 BC–500 BC) was marked by an increase in population density, establishment ofpalisadedsettlements (gords) and the expansion ofLusatian culture.[32][33]A significant archaeological find fromthe protohistory of Polandis a fortified settlement atBiskupin,attributed to the Lusatian culture of theLate Bronze Age(mid-8th century BC).[34]

Throughoutantiquity(400 BC–500 AD), many distinct ancient populations inhabited the territory of present-day Poland, notablyCeltic,Scythian,Germanic,Sarmatian,BalticandSlavictribes.[35]Furthermore, archaeological findings confirmed the presence ofRoman Legionssent to protect theamber trade.[36]ThePolish tribesemerged following thesecond wave of the Migration Periodaround the 6th century AD;[22]they wereSlavicand may have included assimilated remnants of peoples that earlier dwelled in the area.[37][38]Beginning in the early 10th century, thePolanswould come to dominate otherLechitictribes in the region, initially forming a tribal federation and later a centralised monarchical state.[39]

Kingdom of Poland

Poland began to form into a recognisable unitary and territorial entity around the middle of the 10th century under thePiast dynasty.[40]In 966, ruler of the PolansMieszko Iaccepted Christianity under the auspices of theRoman Churchwith theBaptism of Poland.[41]In 968, a missionarybishopricwas established inPoznań.AnincipittitledDagome iudexfirst defined Poland's geographical boundaries with its capital inGnieznoand affirmed that its monarchy was under the protection of theApostolic See.[42]The country's early origins were described byGallus AnonymusinGesta principum Polonorum,the oldest Polish chronicle.[43]An important national event of the period was themartyrdomofSaint Adalbert,who was killed byPrussianpagans in 997 and whose remains were reputedly bought back for their weight in gold by Mieszko's successor,Bolesław I the Brave.[42]

In 1000, at theCongress of Gniezno,Bolesław obtained the right ofinvestiturefromOtto III, Holy Roman Emperor,who assented to the creation of additional bishoprics and an archdioceses in Gniezno.[42]Three new dioceses were subsequently established inKraków,Kołobrzeg,andWrocław.[44]Also, Otto bestowed upon Bolesław royalregaliaand a replica of theHoly Lance,which were later used at his coronation as the firstKing of Polandinc. 1025,when Bolesław received permission for his coronation fromPope John XIX.[45][46]Bolesław also expanded the realm considerably by seizing parts of GermanLusatia,CzechMoravia,Upper Hungary,and southwestern regions of theKievan Rus'.[47]

The transition frompaganismin Poland was not instantaneous and resulted in thepagan reaction of the 1030s.[48]In 1031,Mieszko II Lambertlost the title of king and fled amidst the violence.[49]The unrest led to the transfer of the capital to Kraków in 1038 byCasimir I the Restorer.[50]In 1076,Bolesław IIre-instituted the office of king, but was banished in 1079 for murdering his opponent,Bishop Stanislaus.[51]In 1138, the countryfragmentedinto five principalities whenBolesław III Wrymouthdivided his lands among his sons.[24]These wereLesser Poland,Greater Poland,Silesia,MasoviaandSandomierz,with intermittent hold overPomerania.[52]In 1226,Konrad I of Masoviainvited theTeutonic Knightsto aid in combating theBalticPrussians; a decision that later led to centuries of warfare with the Knights.[53]

In the first half of the 13th century,Henry I the BeardedandHenry II the Piousaimed to unite the fragmented dukedoms, but theMongol invasionand the death of Henry II inbattlehindered the unification.[54][55]As a result of the devastation which followed, depopulation and the demand for craft labour spurred a migration ofGerman and Flemish settlersinto Poland, which was encouraged by the Polish dukes.[56]In 1264, theStatute of Kaliszintroduced unprecedented autonomy for thePolish Jews,who came to Poland fleeing persecution elsewhere in Europe.[57]

In 1320,Władysław I the Shortbecame the first king ofa reunified PolandsincePrzemysł IIin 1296,[58]and the first to be crowned atWawel Cathedralin Kraków.[59]Beginning in 1333, the reign ofCasimir III the Greatwas marked by developments incastle infrastructure,army, judiciary anddiplomacy.[60][61]Under his authority, Poland transformed into a major European power; he instituted Polish rule overRutheniain 1340 and imposed quarantine that prevented the spread ofBlack Death.[62][63]In 1364, Casimir inaugurated theUniversity of Kraków,one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in Europe.[64]Upon his death in 1370, the Piast dynasty came to an end.[65]He was succeeded by his closest male relative,Louis of Anjou,who ruled Poland,Hungary,andCroatiain apersonal union.[66]Louis' younger daughterJadwigabecame Poland's first female monarch in 1384.[66]

In 1386, Jadwiga of Poland entered a marriage of convenience withWładysław II Jagiełło,theGrand Duke of Lithuania,thus forming theJagiellonian dynastyand thePolish–Lithuanian unionwhich spanned the lateMiddle Agesand earlyModern Era.[67]The partnership between Poles and Lithuanians brought the vast multi-ethnicLithuanianterritories into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for its inhabitants, who coexisted in one of the largest Europeanpolitical entitiesof the time.[68]

In the Baltic Sea region, the struggle of Poland and Lithuania with theTeutonic Knightscontinued and culminated at theBattle of Grunwaldin 1410, where a combined Polish-Lithuanian army inflicted a decisive victory against them.[69]In 1466, after theThirteen Years' War,kingCasimir IV Jagiellongave royal consent to thePeace of Thorn,which created the futureDuchy of Prussiaunder Polish suzerainty and forced the Prussian rulers to paytributes.[24]The Jagiellonian dynasty also established dynastic control over the kingdoms ofBohemia(1471 onwards) and Hungary.[70]In the south, Poland confronted theOttoman Empire(at theVarna Crusade) and theCrimean Tatars,and in the east helped Lithuania to combatRussia.[24]

Poland was developing as afeudalstate, with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly powerfullanded nobilitythat confined the population to private manorial farmstead known asfolwarks.[71]In 1493,John I Albertsanctioned the creation of abicameral parliamentcomposed of a lower house, theSejm,and an upper house, theSenate.[72]TheNihil noviact adopted by the PolishGeneral Sejmin 1505, transferred most of thelegislative powerfrom the monarch to the parliament, an event which marked the beginning of the period known asGolden Liberty,when the state was ruled by the seemingly free and equalPolish nobles.[73]

The 16th century sawProtestant Reformationmovements making deep inroads into Polish Christianity, which resulted in the establishment of policies promoting religious tolerance, unique in Europe at that time.[74]This tolerance allowed the country to avoid the religious turmoil andwars of religionthat beset Europe.[74]In Poland,Nontrinitarian Christianitybecame the doctrine of the so-calledPolish Brethren,who separated from theirCalvinistdenomination and became the co-founders of globalUnitarianism.[75]

The EuropeanRenaissanceevoked underSigismund I the OldandSigismund II Augustusa sense of urgency in the need to promote acultural awakening.[24]During thePolish Golden Age,the nation's economy and culture flourished.[24]The Italian-bornBona Sforza,daughter of theDuke of Milanand queen consort to Sigismund I, made considerable contributions toarchitecture,cuisine,language and court customs atWawel Castle.[24]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

TheUnion of Lublinof 1569 established thePolish–Lithuanian Commonwealth,a unified federal state with anelective monarchy,but largely governed by the nobility.[76]The latter coincided with a period of prosperity; the Polish-dominated union thereafter becoming a leading power and a major cultural entity, exercising political control over parts of Central,Eastern,Southeasternand Northern Europe. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth occupied approximately 1 million km2(390,000 sq mi)at its peakand was the largest state in Europe.[77][78]Simultaneously, Poland imposedPolonisationpolicies in newly acquired territories which were met with resistance from ethnic and religious minorities.[76]

In 1573,Henry de Valois of France,the first elected king, approbated theHenrician Articleswhich obliged future monarchs to respect the rights of nobles.[79]When he left Poland to becomeKing of France,his successor,Stephen Báthory,led a successfulcampaignin theLivonian War,granting Poland morelands across the eastern shoresof the Baltic Sea.[80]State affairs were then headed byJan Zamoyski,theCrown Chancellor.[81]Stephen's successor,Sigismund III,defeated a rivalHabsburgelectoral candidate,Archduke Maximilian III,in theWar of the Polish Succession (1587–1588).In 1592, Sigismund succeeded his father andJohn Vasa,inSweden.[82]ThePolish-Swedish unionendured until 1599, when he wasdeposedby the Swedes.[83]

In 1609, SigismundinvadedRussiawhich was engulfed in acivil war,[24]and a year later the Polishwinged hussarunits underStanisław ŻółkiewskioccupiedMoscow for two years after defeating the Russians atKlushino.[24]Sigismund also countered theOttoman Empirein the southeast; atKhotynin 1621Jan Karol Chodkiewiczachieved a decisive victory against the Turks, which ushered the downfall of SultanOsman II.[84][85]

Sigismund's long reign in Poland coincided with theSilver Age.[86]The liberalWładysław IVeffectively defended Poland's territorial possessions but after his death the vast Commonwealth began declining from internal disorder and constant warfare.[87][88]In 1648, the Polish hegemony over Ukraine sparked theKhmelnytsky Uprising,[89]followed by the decimatingSwedish Delugeduring theSecond Northern War,[90]and Prussia'sindependencein 1657.[90]In 1683,John III Sobieskire-established military prowess when he halted the advance of anOttoman Armyinto Europe at theBattle of Vienna.[91]TheSaxonera, underAugustus IIandAugustus III,saw neighboring powers grow in strength at the expense of Poland. Both Saxon kings faced opposition fromStanisław Leszczyńskiduring theGreat Northern War(1700) and theWar of the Polish Succession (1733).[92]

Partitions

Theroyal electionof 1764 resulted in the elevation ofStanisław II Augustus Poniatowskito the monarchy.[93]His candidacy was extensively funded by his sponsor and former lover, EmpressCatherine II of Russia.[94]The new king maneuvered between his desire to implement necessary modernising reforms, and the necessity to remain at peace with surrounding states.[95]His ideals led to the formation of the 1768Bar Confederation,a rebellion directed against the Poniatowski and all external influence, which ineptly aimed to preserve Poland's sovereignty and privileges held by the nobility.[96]The failed attempts at government restructuring as well as the domestic turmoil provoked its neighbours to invade.[97]

In 1772, theFirst Partition of the Commonwealthby Prussia, Russia and Austria took place; an act which thePartition Sejm,under considerable duress, eventually ratified as afait accompli.[98]Disregarding the territorial losses, in 1773 a plan of critical reforms was established, in which theCommission of National Education,the first government education authority in Europe, was inaugurated.[99]Corporal punishment of schoolchildren was officially prohibited in 1783. Poniatowski was the head figure of theEnlightenment,encouraged the development of industries, and embraced republicanneoclassicism.[100]For his contributions to the arts and sciences he was awarded aFellowship of the Royal Society.[101]

In 1791,Great Sejm parliamentadopted the3 May Constitution,the first set of supreme national laws, and introduced aconstitutional monarchy.[102]TheTargowica Confederation,an organisation of nobles and deputies opposing the act, appealed to Catherine and caused the1792 Polish–Russian War.[103]Fearing the reemergence of Polish hegemony, Russia and Prussia arranged and in 1793 executed, theSecond Partition,which left the country deprived of territory and incapable of independent existence. On 24 October 1795, the Commonwealth waspartitioned for the third timeand ceased to exist as a territorial entity.[104][105]Stanisław Augustus, the last King of Poland, abdicated the throne on 25 November 1795.[106]

Era of insurrections

The Polish peoplerose several times against the partitionersand occupying armies. An unsuccessful attempt at defending Poland's sovereignty took place in the 1794Kościuszko Uprising,where a popular and distinguished generalTadeusz Kościuszko,who had several years earlier served underGeorge Washingtonin theAmerican Revolutionary War,led Polish insurgents.[107]Despite the victory at theBattle of Racławice,his ultimate defeat ended Poland's independent existencefor 123 years.[108]

In 1806, aninsurrectionorganised byJan Henryk Dąbrowskiliberated western Poland ahead ofNapoleon'sadvance into Prussia during theWar of the Fourth Coalition.In accordance with the 1807Treaty of Tilsit,Napoleon proclaimed theDuchy of Warsaw,aclient stateruled by his allyFrederick Augustus I of Saxony.The Poles actively aided French troops in theNapoleonic Wars,particularly those underJózef Poniatowskiwho becameMarshal of Franceshortly before his death atLeipzigin 1813.[109]In the aftermath of Napoleon's exile, the Duchy of Warsaw was abolished at theCongress of Viennain 1815 and its territory was divided into RussianCongress Kingdom of Poland,the PrussianGrand Duchy of Posen,andAustrian Galiciawith theFree City of Kraków.[110]

In 1830,non-commissioned officersat Warsaw'sOfficer Cadet Schoolrebelled in what was theNovember Uprising.[111]After its collapse, Congress Poland lost itsconstitutional autonomy,armyand legislative assembly.[112]During theEuropean Spring of Nations,Poles took up arms in theGreater Poland Uprising of 1848to resistGermanisation,but its failure saw duchy's status reduced to a mereprovince;and subsequent integration into theGerman Empirein 1871.[113]In Russia, the fall of theJanuary Uprising(1863–1864) prompted severepolitical, social and cultural reprisals,followed by deportations andpogromsof the Polish-Jewish population. Towards the end of the 19th century, Congress Poland became heavily industrialised; its primary exports being coal,zinc,iron and textiles.[114][115]

Second Polish Republic

In the aftermath ofWorld War I,theAlliesagreed on the reconstitution of Poland, confirmed through theTreaty of Versaillesof June 1919.[116]A total of 2 million Polish troops fought with the armies of the three occupying powers, and over 450,000 died.[117]Following thearmistice with Germanyin November 1918, Poland regained its independence as theSecond Polish Republic.[118]

The Second Polish Republic reaffirmed its sovereignty aftera series of military conflicts,most notably thePolish–Soviet War,when Poland inflicted a crushing defeat on theRed Armyat theBattle of Warsaw.[119]

The inter-war period heralded a new era of Polish politics. Whilst Polish political activists had faced heavy censorship in the decades up untilWorld War I,a new political tradition was established in the country. Many exiled Polish activists, such asIgnacy Jan Paderewski,who would later become prime minister, returned home. A significant number of them then went on to take key positions in the newly formed political and governmental structures. Tragedy struck in 1922 whenGabriel Narutowicz,inaugural holder of the presidency, was assassinated at theZachętaGallery in Warsaw by a painter and right-wing nationalistEligiusz Niewiadomski.[120]

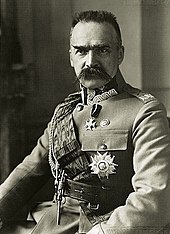

In 1926, theMay Coup,led by the hero of the Polish independence campaign MarshalJózef Piłsudski,turned rule of the Second Polish Republic over to the nonpartisanSanacja(Healing) movement to prevent radical political organisations on both the left and the right from destabilizing the country.[121]By the late 1930s, due to increased threats posed by political extremism inside the country, the Polish government became increasingly heavy-handed, banning a number of radical organisations, including communist and ultra-nationalist political parties, which threatened the stability of the country.[122]

World War II

World War II began with theNazi Germaninvasion of Polandon 1 September 1939, followed by theSoviet invasion of Polandon 17 September. On 28 September 1939,Warsaw fell.As agreed in theMolotov–Ribbentrop Pact,Poland was split into two zones,one occupied by Nazi Germany,the other bythe Soviet Union.In 1939–1941, the Soviets deported hundreds of thousands of Poles. The SovietNKVDexecuted thousands of Polish prisoners of war (among other incidents in theKatyn massacre) ahead ofOperation Barbarossa.[123]German planners had in November 1939 called for "the complete destruction of all Poles" and their fate as outlined in the genocidalGeneralplan Ost.[124]

Poland made the fourth-largest troop contribution in Europe,[125][126][127]and its troops served both thePolish Government in Exilein thewestand Soviet leadership in theeast.Polish troops played an important role in theNormandy,Italian,North African CampaignsandNetherlandsand are particularly remembered for theBattle of BritainandBattle of Monte Cassino.[128][129]Polish intelligence operatives proved extremely valuable to the Allies, providing much of the intelligence from Europe and beyond,[130]Polish code breakerswere responsible forcracking the Enigma cipherand Polish scientists participating in theManhattan Projectwere co-creators of the Americanatomic bomb.In the east, the Soviet-backedPolish 1st Armydistinguished itself in the battles forWarsawandBerlin.[131]

Thewartime resistance movement,and theArmia Krajowa(Home Army), fought against German occupation. It was one of the three largest resistance movements of the entire war, and encompassed a range of clandestine activities, which functioned as anunderground statecomplete withdegree-awarding universitiesanda court system.[132]The resistance was loyal to the exiled government and generally resented the idea of a communist Poland; for this reason, in the summer of 1944 it initiatedOperation Tempest,of which theWarsaw Uprisingthat began on 1 August 1944 is the best-known operation.[131][133]

Nazi German forces under orders fromAdolf Hitlerset up six Germanextermination campsin occupied Poland, includingTreblinka,MajdanekandAuschwitz.The Germanstransported millions of Jewsfrom across occupied Europe to be murdered in those camps.[134][135]Altogether, 3 million Polish Jews[136][137]– approximately 90% of Poland's pre-war Jewry – and between 1.8 and 2.8 million ethnic Poles[138][139][140]were killed during the Germanoccupation of Poland,including between 50,000 and 100,000 members of the Polishintelligentsia– academics, doctors, lawyers, nobility and priesthood. During the Warsaw Uprising alone, over 150,000 Polish civilians were killed, most were murdered by the Germans during theWolaandOchotamassacres.[141][142]Around 150,000 Polish civilians were killed by Soviets between 1939 and 1941 during the Soviet Union's occupation of eastern Poland (Kresy), and another estimated 100,000 Poles were murdered by theUkrainian Insurgent Army(UPA) between 1943 and 1944 in what became known as theWołyń Massacres.[143][144]Of all the countriesin the war, Poland lost the highest percentage of its citizens: around 6 million perished – more than one-sixth of Poland's pre-war population –half of themPolish Jews.[145][146][147]About 90% of deaths were non-military in nature.[148]

In 1945, Poland's borderswere shifted westwards.Over two million Polish inhabitants ofKresywere expelledalong theCurzon LinebyStalin.[149]The western border became theOder-Neisse line.As a result, Poland's territory was reduced by 20%, or 77,500 square kilometres (29,900 sq mi). The shift forced the migration ofmillions of other people,most of whom were Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews.[150][151][152]

Post-war communism

At the insistence ofJoseph Stalin,theYalta Conferencesanctioned the formation of a new provisional pro-Communist coalition government in Moscow, which ignored thePolish government-in-exilebased in London. This action angered many Poles who considered it abetrayalby the Allies. In 1944, Stalin had made guarantees toChurchillandRooseveltthat he would maintain Poland's sovereignty and allow democratic elections to take place. However, upon achieving victory in 1945, the elections organised by the occupying Soviet authorities were falsified and were used to provide a veneer of legitimacy for Soviet hegemony over Polish affairs. The Soviet Union instituted a newcommunistgovernment in Poland, analogous to much of the rest of theEastern Bloc.As elsewhere in Communist Europe,the Soviet influence over Poland was met witharmed resistancefrom the outset which continued into the 1950s.[153]

Despite widespread objections, the new Polish government accepted the Soviet annexation of the pre-war eastern regions of Poland[154](in particular the cities ofWilnoandLwów) and agreed to the permanent garrisoning ofRed Armyunits on Poland's territory. Military alignment within theWarsaw Pactthroughout theCold Warcame about as a direct result of this change in Poland's political culture. In the European scene, it came to characterise the full-fledged integration of Poland into the brotherhood of communist nations.[155]

The new communist government took control with the adoption of theSmall Constitutionon 19 February 1947. ThePolish People's Republic(Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa)was officially proclaimed in 1952.In 1956, after the death ofBolesław Bierut,the régime ofWładysław Gomułkabecame temporarily more liberal, freeing many people from prison and expanding some personal freedoms.Collectivisation in the Polish People's Republicfailed. A similar situation repeated itself in the 1970s underEdward Gierek,but most of the time persecution ofanti-communist oppositiongroups persisted. Despite this, Poland was at the time considered to be one of the least oppressive states of the Eastern Bloc.[156]

Labour turmoil in 1980 led to the formation of the independent trade union "Solidarity"("Solidarność"), which over time became a political force. Despite persecution and imposition ofmartial law in 1981by GeneralWojciech Jaruzelski,it eroded the dominance of thePolish United Workers' Partyand by 1989 had triumphed in Poland's firstpartially free and democratic parliamentary electionssince the end of the Second World War.Lech Wałęsa,a Solidarity candidate, eventuallywon the presidency in 1990.The Solidarity movement heralded thecollapse of communist regimes and parties across Europe.[157]

Third Polish Republic

Ashock therapyprogram, initiated byLeszek Balcerowiczin the early 1990s, enabled the country to transform itsSoviet-styleplanned economyinto amarket economy.[158]As with otherpost-communist countries,Poland suffered temporary declines in social, economic, and living standards,[159]but it became the first post-communist country to reach its pre-1989GDP levelsas early as 1995, although the unemployment rate increased.[160]Poland became a member of theVisegrád Groupin 1991,[161]and joinedNATOin 1999.[162]Poles then voted to join theEuropean Unionina referendumin June 2003,[163]withPoland becoming a full memberon 1 May 2004, following theconsequent enlargement of the organisation.[164]

Poland has joined theSchengen Areain 2007, as a result of which,the country's borderswith other member states of the European Union were dismantled, allowing forfull freedom of movementwithin most of the European Union.[165]On 10 April 2010, thePresident of PolandLech Kaczyński,along with 89 other high-ranking Polish officialsdied in a plane crashnearSmolensk,Russia.[166]

In 2011, the rulingCivic Platformwonparliamentary elections.[167]In 2014, thePrime Minister of Poland,Donald Tusk,was chosen to bePresident of the European Council,and resigned as prime minister.[168]The2015and2019 electionswere won by the national-conservativeLaw and JusticeParty (PiS) led byJarosław Kaczyński,[169][170]resulting in increasedEuroscepticismandincreased frictionwith the European Union.[171]In December 2017,Mateusz Morawieckiwas sworn in as the Prime Minister, succeedingBeata Szydlo,in office since 2015. PresidentAndrzej Duda,supported by Law and Justice party, was re-elected in the 2020 presidentialelection.[172]As of November 2023[update],theRussian invasion of Ukrainehad led to 17 millionUkrainian refugeescrossing the border to Poland.[173]As of November 2023[update],0.9 million of those had stayed in Poland.[173]In October 2023, the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party won the largest share of the vote in theelection,but lost its majority in parliament. In December 2023, Donald Tusk became the new Prime Minister leading a coalition made up ofCivic Coalition,Third Way,andThe Left.Law and Justice became the leading opposition party.[174]

Geography

Poland covers an administrative area of 312,722 km2(120,743 sq mi), and is theninth-largest country in Europe.Approximately 311,895 km2(120,423 sq mi) of the country's territory consists of land, 2,041 km2(788 sq mi) is internal waters and 8,783 km2(3,391 sq mi) is territorial sea.[175]Topographically, the landscape of Poland is characterised by diverselandforms,water bodiesandecosystems.[176]The central and northern region bordering theBaltic Sealie within the flatCentral European Plain,but its south is hilly and mountainous.[177]The averageelevation above the sea levelis estimated at 173 metres.[175]

The country has a coastline spanning 770 km (480 mi); extending from the shores of the Baltic Sea, along theBay of Pomeraniain the west to theGulf of Gdańskin the east.[175]The beach coastline is abundant insand dune fieldsorcoastal ridgesand is indented byspitsand lagoons, notably theHel Peninsulaand theVistula Lagoon,which is shared with Russia.[178]The largest Polish island on the Baltic Sea isWolin,located withinWolin National Park.[179]Poland also shares theSzczecin Lagoonand theUsedomisland with Germany.[180]

The mountainous belt in the extreme south of Poland is divided into two majormountain ranges;theSudetesin the west and theCarpathiansin the east. The highest part of the Carpathian massif are theTatra Mountains,extending along Poland's southern border.[181]Poland's highest point isMount Rysyat 2,501 metres (8,205 ft) in elevation, located in the Tatras.[182]The highest summit of the Sudetes massif isMount Śnieżkaat 1,603.3 metres (5,260 ft), shared with the Czech Republic.[183]The lowest point in Poland is situated atRaczki Elbląskiein theVistula Delta,which is 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) below sea level.[175]

Poland'slongest riversare theVistula,theOder,theWarta,and theBug.[175]The country also possesses one of the highest densities of lakes in the world, numbering around ten thousand and mostly concentrated in the north-eastern region ofMasuria,within theMasurian Lake District.[184]The largest lakes, covering more than 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi), areŚniardwyandMamry,and the deepest isLake Hańczaat 108.5 metres (356 ft) in depth.[175]

Climate

The climate of Poland istemperate transitional,and varies fromoceanicin the north-west tocontinentalin the south-east.[185]The mountainous southern fringes are situated within analpine climate.[185]Poland is characterised by warm summers, with a mean temperature of around 20 °C (68.0 °F) in July, and moderately cold winters averaging −1 °C (30.2 °F) in December.[186]The warmest and sunniest part of Poland isLower Silesiain the southwest and the coldest region is the northeast corner, aroundSuwałkiinPodlaskie province,where the climate is affected bycold frontsfromScandinaviaandSiberia.[187]Precipitationis more frequent during the summer months, with highest rainfall recorded from June to September.[186]

There is a considerable fluctuation in day-to-day weather and the arrival of a particular season can differ each year.[185]Climate changeand other factors have further contributed to interannualthermal anomaliesand increased temperatures; the average annual air temperature between 2011 and 2020 was 9.33 °C (48.8 °F), around 1.11 °C higher than in the 2001–2010 period.[187]Winters are also becoming increasingly drier, with lesssleetand snowfall.[185]

Biodiversity

Phytogeographically,Poland belongs to the Central European province of theCircumboreal Regionwithin theBoreal Kingdom.The country has fourPalearctic ecoregions– Central, Northern, Western Europeantemperate broadleaf and mixed forest,and theCarpathian montane conifer.Forests occupy 31% of Poland's land area, the largest of which is theLower Silesian Wilderness.[188]The most commondeciduous treesfound across the country areoak,maple,andbeech;the most common conifers arepine,spruce,andfir.[189]An estimated 69% of all forests areconiferous.[190]

Thefloraandfaunain Poland is that ofContinental Europe,with thewisent,white storkandwhite-tailed eagledesignated as national animals, and thered common poppybeing the unofficial floral emblem.[191]Among the most protected species is theEuropean bison,Europe's heaviest land animal, as well as theEurasian beaver,thelynx,thegray wolfand theTatra chamois.[175]The region was also home to the extinctaurochs,the last individual dying in Poland in 1627.[192]Game animals such asred deer,roe deer,andwild boarare found in most woodlands.[193]Poland is also a significant breeding ground formigratory birdsand hosts around one quarter of the global population of white storks.[194]

Around 315,100 hectares (1,217 sq mi), equivalent to 1% of Poland's territory, is protected within 23Polish national parks,two of which –BiałowieżaandBieszczady– areUNESCO World Heritage Sites.[195]There are 123 areas designated aslandscape parks,along with numerousnature reservesand otherprotected areasunder theNatura 2000network.[196]

Government and politics

Poland is aunitarysemi-presidential republic[198]and arepresentative democracy,with apresidentas thehead of state.[199]The executive power is exercised further by theCouncil of Ministersand theprime ministerwho acts as thehead of government.[199]The council's individual members are selected by the prime minister, approved by parliament and sworn in by the president.[199]The head of state is elected bypopular votefor a five-year term.[200]The current president isAndrzej Dudaand the prime minister isDonald Tusk.

Poland'slegislativeassembly is abicameralparliament consisting of a 460-member lower house (Sejm) and a 100-member upper house (Senate).[201]The Sejm is elected underproportional representationaccording to thed'Hondt methodfor vote-seat conversion.[202]The Senate is elected under thefirst-past-the-postelectoral system, with one senator being returned from each of the one hundred constituencies.[203]The Senate has the right to amend or reject a statute passed by the Sejm, but the Sejm may override the Senate's decision with a majority vote.[204]

With the exception of ethnic minority parties, only candidates ofpolitical partiesreceiving at least 5% of the total national vote can enter the Sejm.[203]Both the lower and upper houses of parliament in Poland are elected for a four-year term and each member of the Polish parliament is guaranteedparliamentary immunity.[205]Under current legislation, a person must be 21 years of age or over to assume the position of deputy, 30 or over to become senator and 35 to run in a presidential election.[205]

Members of the Sejm and Senate jointly form theNational Assembly of the Republic of Poland.[206]The National Assembly, headed by theSejm Marshal,is formed on three occasions – when a new president takes theoath of office;when an indictment against the president is brought to theState Tribunal;and in case a president's permanent incapacity to exercise his duties due to the state of his health is declared.[206]

Administrative divisions

Poland is divided into 16 provinces or states known asvoivodeships.[207]As of 2022, the voivodeships are subdivided into 380 counties (powiats), which are further fragmented into 2,477 municipalities (gminas).[207]Major cities normally have the status of bothgminaandpowiat.[207]The provinces are largely founded on the borders ofhistoric regions,or named for individual cities.[208]Administrative authority at the voivodeship level is shared between a government-appointed governor (voivode), an elected regional assembly (sejmik) and avoivodeship marshal,an executive elected by the assembly.[208]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Law

TheConstitution of Polandis the enacted supreme law, and Polish judicature is based on the principle of civil rights, governed by the code ofcivil law.[210]The current democratic constitution was adopted by theNational Assembly of Polandon 2 April 1997; it guarantees amulti-party statewith freedoms of religion, speech and gatherings, prohibits the practices of forcedmedical experimentation,torture orcorporal punishment,and acknowledges the inviolability of the home, the right to form trade unions, and the right tostrike.[211]

Thejudiciaryin Poland is composed of theSupreme Courtas the country's highest judicial organ, theSupreme Administrative Courtfor the judicial control of public administration, Common Courts (District,Regional,Appellate) and theMilitary Court.[212]TheConstitutionaland State Tribunals are separate judicial bodies, which rule the constitutional liability of people holding the highest offices of state and supervise the compliance ofstatutory law,thus protecting the Constitution.[213]Judges are nominated by theNational Council of the Judiciaryand are appointed for life by thepresident.[213]With the approval of the Senate, the Sejm appoints anombudsmanfor a five-year term to guard the observance of social justice.[203]

Poland has a lowhomiciderate at 0.7 murders per 100,000 people, as of 2018.[214]Rape, assault and violent crime remain at a very low level.[215]The country has imposed strict regulations onabortion,which is permitted only in cases of rape, incest or when the woman's life is in danger;congenital disorderandstillbirthare not covered by the law, prompting some women to seek abortion abroad.[216]

Historically, the most significant Polish legal act is theConstitution of 3 May 1791.Instituted to redress long-standing political defects of thefederativePolish–Lithuanian Commonwealthand itsGolden Liberty,it was the first modern constitution in Europe and influenced many laterdemocratic movementsacross the globe.[217][218][219]In 1918, theSecond Polish Republicbecame one of the first countries to introduce universalwomen's suffrage.[220]

Foreign relations

Poland is amiddle powerand is transitioning into aregional powerin Europe.[221][222]It has a total of 53 representatives in theEuropean Parliamentas of 2024.Warsawserves as the headquarters forFrontex,the European Union's agency for external border security as well asODIHR,one of the principal institutions of theOSCE.[223][224]Apart from the European Union, Poland has been a member ofNATO,the United Nations, and theWTO.

In recent years, Poland significantly strengthened itsrelationswith the United States, thus becoming one of its closestalliesand strategic partners in Europe.[225]Historically, Poland maintained strongcultural and politicalties to Hungary; this special relationship was recognised by the parliaments of both countries in 2007 with the joint declaration of 23 March as "The Day of Polish-Hungarian Friendship".[226]

Military

The Polish Armed Forces are composed of five branches – theLand Forces,theNavy,theAir Force,theSpecial Forcesand theTerritorial Defence Force.[227]The military is subordinate to theMinistry of National Defence of the Republic of Poland.[227]However, its commander-in-chief in peacetime is the president, who nominates officers, the Minister for National Defence and the chief of staff.[227]Polish military tradition is generally commemorated by theArmed Forces Day,celebrated annually on 15 August.[228]As of 2022, the Polish Armed Forces have a combined strength of 114,050 active soldiers, with a further 75,400 active in thegendarmerieanddefence force.[229]

Poland ranks14th in the worldin terms of military expenditures; the country allocates 3.8% of its total GDP on military spending, equivalent to approximately US$31.6 billion in 2023.[230]From 2022, Poland initiated a programme of mass modernisation of its armed forces, in close cooperation with American, South Korean and local Polishdefence manufacturers.[231]Also, the Polish military is set to increase its size to 250,000 enlisted and officers, and 50,000 defence force personnel.[232]According toSIPRI,the country exported €487 million worth of arms and armaments to foreign countries in 2020.[233]

Compulsorymilitary servicefor men, who previously had to serve for nine months, was discontinued in 2008.[234]Polish military doctrine reflects the same defensive nature as that of its NATO partners and the country actively hosts NATO'smilitary exercises.[229]Since 1953, the country has been a large contributor to various United Nations peacekeeping missions,[235]and currently maintains military presence in the Middle East, Africa, theBaltic statesand southeastern Europe.[229]

Security, law enforcement and emergency services

Thanks to its location, Poland is a country essentially free from the threat of natural disasters such asearthquakes,volcanic eruptions,tornadoesandtropical cyclones.However,floodshave occurred in low-lying areas from time to time during periods of extreme rainfall (e.g. during the2010 Central European floods).

Law enforcement in Poland is performed by several agencies which are subordinate to theMinistry of Interior and Administration– theState Police(Policja), assigned to investigate crimes or transgression; theMunicipal City Guard,which maintains public order; and several specialised agencies, such as thePolish Border Guard.[236]Private security firms are also common, although they possess no legal authority to arrest or detain a suspect.[236][237]Municipal guards are primarily headed by provincial, regional or city councils; individual guards are not permitted to carryfirearmsunless instructed by the superior commanding officer.[238]Security service personnel conduct regular patrols in both large urban areas or smaller suburban localities.[239]

TheInternal Security Agency(ABW, or ISA in English) is the chiefcounterintelligence instrumentsafeguarding Poland's internal security, along withAgencja Wywiadu(AW) which identifies threats and collects secret information abroad.[240]TheCentral Investigation Bureau of Police(CBŚP) and theCentral Anticorruption Bureau(CBA) are responsible for countering organised crime and corruption in state and private institutions.[241][242]

Emergency services in Poland consist of theemergency medical services,search and rescueunits of thePolish Armed ForcesandState Fire Service.Emergency medical services in Poland are operated by local and regional governments,[243]but are a part of the centralised national agency – theNational Medical Emergency Service(Państwowe Ratownictwo Medyczne).[244]

Economy

| GDP (PPP) | $1.890 trillion(2024)[14] |

|---|---|

| Nominal GDP | $862.9 billion(2024)[14] |

| Real GDP growth | 5.3%(2022)[245] |

| CPIinflation | 2.5%(May 2024)[246] |

| Employment-to-population ratio | 57%(2022)[247] |

| Unemployment | 2.8%(2023)[248] |

| Total public debt | $340 billion(2022)[249] |

As of 2023[update],Poland's economy and gross domestic product (GDP) is the sixth largest in the European Union bynominal standardsand the fifth largest bypurchasing power parity.It is also one of the fastest growing within the Union and reached adeveloped marketstatus in 2018.[250]The unemployment rate published byEurostatin 2023 amounted to 2.8%, which was the second-lowest in the EU.[248]As of 2023[update],around 62% of the employed population works in theservice sector,29% in manufacturing, and 8% in the agricultural sector.[251]Although Poland is a member of theEuropean single market,the country has not adopted theEuroas legal tender and maintains its own currency – thePolish złoty(zł, PLN).

Poland is the regional economic leader in Central Europe, with nearly 40 per cent of the 500 biggest companies in the region (by revenues) as well as ahigh globalisation rate.[252]The country's largest firms compose theWIG20andWIG30indexes,which is traded on theWarsaw Stock Exchange.According to reports made by theNational Bank of Poland,the value of Polish foreign direct investments reached almost 300 billionPLNat the end of 2014. TheCentral Statistical Officeestimated that in 2014 there were 1,437 Polish corporations with interests in 3,194 foreign entities.[253]

Poland has the largest banking sector in Central Europe,[254]with 32.3 branches per 100,000 adults.[255]It was the only European economy to have avoided therecession of 2008.[256]The country is the19th largest exporterof goods and services in the world.[257]Exports of goods and services are valued at approximately 58% of GDP, as of 2023.[258]Since 2019, workers under the age of 26 are exempt from paying theincome tax.[259]As of 2024, Poland holds the world's 12th largestgold reserve,estimated at around 377 tonnes.[260]

Tourism

In 2020, the total value of thetourism industryin Poland was 104.3 billionPLN,then equivalent to 4.5% of the Polish GDP.[261]Tourism contributes considerably to the overall economy and makes up a relatively large proportion of the country's service market.[262]Nearly 200,000 people were employed in theaccommodation and catering(hospitality) sector in 2020.[261]In 2021, Poland ranked12th most visited countryin the world by international arrivals.[263]

Tourist attractions in Poland vary, from the mountains in the south to the beaches in the north, with a trail of rich architectural and cultural heritage. Among the most recognisable landmarks are Old Towns inKraków,Warsaw,Wrocław(dwarf statues),Gdańsk,Poznań,Lublin,ToruńandZamośćas well as museums, zoological gardens, theme parks and theWieliczka Salt Mine,with its labyrinthine tunnels,underground lakeand chapels carved by miners out ofrock saltbeneath the ground. There areover 100 castlesin the country, largely within theLower Silesian Voivodeship,and also on theTrail of the Eagles' Nests;the largest castle in the world by land area is situated inMalbork.[264][265]The GermanAuschwitz concentration campinOświęcim,and theSkull ChapelinKudowa-Zdrójconstitutedark tourism.[266]Regarding nature based travel, notable sites include theMasurian Lake DistrictandBiałowieża Forestin the east; on the southKarkonosze,theTable Mountainsand theTatra Mountains,whereRysyand theEagle's Pathtrail are located. ThePieninyandBieszczady Mountainslie in the extreme south-east.[267]

Transport

Transport in Poland is provided by means ofrail,road,marine shippingandair travel.The country is part of EU'sSchengen Areaand is an important transport hub due to its strategic geographical position in Central Europe.[268]Some of the longest European routes, including theE30andE40,run through Poland. The country has a good network ofhighwaysconsisting ofexpress roadsandmotorways.As of August 2023, Poland has the world's21st-largest road network,maintaining over 5,000 km (3,100 mi) of highways in use.[269]

In 2022, the nation had 19,393 kilometres (12,050 mi) of railway track, the third longest in the European Union after Germany and France.[270]ThePolish State Railways(PKP) is the dominant railway operator, with certain major voivodeships or urban areas possessing their owncommuterandregional rail.[271]Poland has a number of international airports, the largest of which isWarsaw Chopin Airport.[272]It is the primary global hub forLOT Polish Airlines,the country'sflag carrier.[273]

Seaports exist all along Poland's Baltic coast, with most freight operations usingŚwinoujście,Police,Szczecin,Kołobrzeg,Gdynia,GdańskandElblągas their base. ThePort of Gdańskis the only port in theBaltic Seaadapted to receive oceanic vessels.PolferriesandUnity Lineare the largest Polish ferry operators, with the latter providingroll-on/roll-offandtrain ferryservices toScandinavia.[274]

Energy

The electricity generation sector in Poland is largelyfossil-fuel–based. Coal production in Poland is a major source of employment and the largest source of the nation'sgreenhouse gas emissions.[275]Many power plants nationwide use Poland's position as a major European exporter of coal to their advantage by continuing to use coal as the primary raw material in the production of their energy. The three largest Polish coal mining firms (Węglokoks,Kompania WęglowaandJSW) extract around 100 million tonnes of coal annually.[276]After coal, Polish energy supply relies significantly on oil—the nation is the third-largest buyer of Russian oil exports to the EU.[277]

The newEnergy Policy of Poland until 2040(EPP2040) would reduce the share of coal andlignitein electricity generation by 25% from 2017 to 2030. The plan involves deploying new nuclear plants, increasing energy efficiency, and decarbonising the Polish transport system in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prioritise long-term energy security.[275][278]

Science and technology

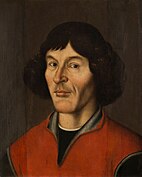

Over the course of history, the Polish people have made considerable contributions in the fields of science, technology and mathematics.[280]Perhaps the most renowned Pole to support this theory wasNicolaus Copernicus(Mikołaj Kopernik), who triggered theCopernican Revolutionby placing theSun rather than the Earth at the center of the universe.[281]He also derived aquantity theory of money,which made him a pioneer of economics. Copernicus' achievements and discoveries are considered the basis of Polish culture and cultural identity.[282]Poland was ranked 40th in theGlobal Innovation Indexin 2024.[283]

Poland's tertiary education institutions; traditionaluniversities,as well as technical, medical, and economic institutions, employ around tens of thousands of researchers and staff members. There are hundreds of research and development institutes.[284]However, in the 19th and 20th centuries many Polish scientists worked abroad; one of the most important of these exiles wasMarie Curie,a physicist and chemist who lived much of her life in France. In 1925, she established Poland'sRadium Institute.[279]

In the first half of the 20th century, Poland was a flourishing centre of mathematics. Outstanding Polish mathematicians formed theLwów School of Mathematics(withStefan Banach,Stanisław Mazur,Hugo Steinhaus,Stanisław Ulam) andWarsaw School of Mathematics(withAlfred Tarski,Kazimierz Kuratowski,Wacław SierpińskiandAntoni Zygmund). Numerous mathematicians, scientists, chemists or economists emigrated due to historic vicissitudes, among themBenoit Mandelbrot,Leonid Hurwicz,Alfred Tarski,Joseph Rotblatand Nobel Prize laureatesRoald Hoffmann,Georges CharpakandTadeusz Reichstein.

Demographics

Poland has a population of approximately 38.2 million as of 2021, and is theninth-most populous countryin Europe, as well as the fifth-most populous member state of theEuropean Union.[285]It has a population density of 122 inhabitants per square kilometre (320 inhabitants/sq mi).[286]Thetotal fertility ratewas estimated at 1.33 children born to a woman in 2021, which isamong the world's lowest.[287]Furthermore, Poland's population isaging significantly,and the country has amedian ageof 42.2.[288]

Around 60% of the country's population lives in urban areas or major cities and 40% in rural zones.[289]In 2020, 50.2% of Poles resided indetached dwellingsand 44.3% in apartments.[290]The most populous administrative province or state is theMasovian Voivodeshipand the most populous city is the capital,Warsaw,at 1.8 million inhabitants with a further 2–3 million people living in itsmetropolitan area.[291][292][293]Themetropolitan areaofKatowiceis the largest urbanconurbationwith a population between 2.7 million[294]and 5.3 million residents.[295]Population density is higher in the south of Poland and mostly concentrated between the cities ofWrocławandKraków.[296]

In the2011 Polish census,37,310,341 people reportedPolishidentity, 846,719Silesian,232,547Kashubianand 147,814German.Otheridentitieswere reported by 163,363 people (0.41%) and 521,470 people (1.35%) did not specify any nationality.[297]Official population statistics do not include migrant workers who do not possess a permanent residency permit orKarta Polaka.[298]More than 1.7 millionUkrainiancitizens worked legally in Poland in 2017.[299]The number of migrants is rising steadily; the country approved 504,172 work permits for foreigners in 2021 alone.[300]According to theCouncil of Europe,12,731Romani peoplelive in Poland.[301]

| Rank | Name | Voivodeship | Pop. | Rank | Name | Voivodeship | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Warsaw  Kraków |

1 | Warsaw | Masovian | 1,860,281 | 11 | Katowice | Silesian | 285,711 |  Wrocław  Łódź |

| 2 | Kraków | Lesser Poland | 800,653 | 12 | Gdynia | Pomeranian | 245,222 | ||

| 3 | Wrocław | Lower Silesian | 672,929 | 13 | Częstochowa | Silesian | 213,107 | ||

| 4 | Łódź | Łódź | 670,642 | 14 | Radom | Masovian | 201,601 | ||

| 5 | Poznań | Greater Poland | 546,859 | 15 | Toruń | Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 198,273 | ||

| 6 | Gdańsk | Pomeranian | 486,022 | 16 | Rzeszów | Subcarpathian | 195,871 | ||

| 7 | Szczecin | West Pomeranian | 396,168 | 17 | Sosnowiec | Silesian | 193,660 | ||

| 8 | Bydgoszcz | Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 337,666 | 18 | Kielce | Świętokrzyskie | 186,894 | ||

| 9 | Lublin | Lublin | 334,681 | 19 | Gliwice | Silesian | 174,016 | ||

| 10 | Białystok | Podlaskie | 294,242 | 20 | Olsztyn | Warmian-Masurian | 170,225 | ||

Languages

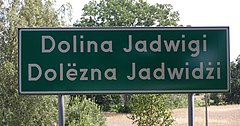

Polishis theofficialand predominant spoken language in Poland, and is one of the officiallanguages of the European Union.[304]It is also asecond languagein parts of neighbouringLithuania,where it is taught in Polish-minority schools.[305][306]Contemporary Poland is a linguisticallyhomogeneousnation, with 97% of respondents declaring Polish as their mother tongue.[307]There are currently 15 minority languages in Poland,[308]including one recognised regional language,Kashubian,which is spoken by approximately 100,000 people on a daily basis in the northern regions ofKashubiaandPomerania.[309]Poland also recognisessecondary administrative languages or auxiliary languages in bilingual municipalities,where bilingual signs and placenames are commonplace.[310]According to theCentre for Public Opinion Research,around 32% of Polish citizens declared knowledge of the English language in 2015.[311]

Religion

According to the 2021 census, 71.3% of all Polish citizens adhere to theRoman Catholic Church,with 6.9% identifying as having no religion and 20.6% refusing to answer.[3]

Poland is one of themost religious countries in Europe,where Roman Catholicism remains a part of national identity and Polish-bornPope John Paul IIis widely revered.[312][313]In 2015, 61.6% of respondents outlined that religion is of high or very high importance.[314]However, church attendance has greatly decreased in recent years; only 28% of Catholics attendedmassweekly in 2021, down from around half in 2000.[315]According toThe Wall Street Journal,"Of [the] more than 100 countries studied by thePew Research Centerin 2018, Poland wassecularizingthe fastest, as measured by the disparity between the religiosity of young people and their elders. "[312]

Freedom of religion in Poland is guaranteed by the Constitution, and Poland'sconcordatwith theHoly Seeenables the teaching of religion in public schools.[316]Historically, the Polish state maintained a high degree ofreligious toleranceand provided asylum for refugees fleeing religious persecution in other parts of Europe.[317]Poland hosted Europe's largestJewish diaspora,and the country was a centre ofAshkenazi Jewishculture and traditional learning until theHolocaust.[318]

Contemporary religious minorities includeOrthodox Christians,Protestants,includingLutheransof theEvangelical-Augsburg Church,Pentecostalsin thePentecostal Church in Poland,Adventistsin theSeventh-day Adventist Church,and other smallerEvangelicaldenominations, includingJehovah's Witnesses,Eastern Catholics,Mariavites,Jews,Muslims(Tatars), andneopagans,some of whom are members of theNative Polish Church.[319]

Health

Medical service providers andhospitalsin Poland are subordinate to theMinistry of Health;it provides administrative oversight and scrutiny of general medical practice, and is obliged to maintain a high standard ofhygieneand patient care. Poland has auniversal healthcare systembased on an all-inclusiveinsurance system;state subsidised healthcare is available to all citizens covered by the general health insurance program of theNational Health Fund(NFZ). Private medical complexes exist nationwide; over 50% of the population uses both public and private sectors.[320][321][322]

According to theHuman Development Reportfrom 2020, the average life expectancy at birth is 79 years (around 75 years for an infant male and 83 years for an infant female);[323]the country has a lowinfant mortality rate(4 per 1,000 births).[324]In 2019, the principal cause of death wasischemic heart disease;diseases of thecirculatory systemaccounted for 45% of all deaths.[325]In the same year, Poland was also the 15th-largest importer ofmedicationsand pharmaceutical products.[326]

Education

TheJagiellonian Universityfounded in 1364 byCasimir IIIinKrakówwas the first institution of higher learning established in Poland, and is one of theoldest universitiesstill in continuous operation.[327]Poland'sCommission of National Education(Komisja Edukacji Narodowej), established in 1773, was the world's first state ministry of education.[328][329]In 2018, theProgramme for International Student Assessment,coordinated by theOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,placed Poland's educational output as one of the highest in the OECD, ranking 5th by student attainment and 6th by student performance in 2022.[330]The study showed that students in Poland perform better academically than in most OECD countries.[331]

The framework for primary, secondary and higher tertiary education are established by theMinistry of Education and Science.One year of kindergarten iscompulsoryfor six-year-olds.[332][333]Primary education traditionally begins at the age of seven, although children aged six can attend at the request of their parents or guardians.[333]Elementary school spans eight grades and secondary schooling is dependent on student preference – a four-year high school (liceum), a five-year technical school (technikum) or variousvocational studies(szkoła branżowa) can be pursued by individual pupils.[333]A liceum or technikum is concluded with a maturity exit exam (matura), which must be passed in order to apply for a university or other institutions of higher learning.[334]

In Poland, there are over 500 university-level institutions,[335]with numerous faculties.[336]TheUniversity of WarsawandWarsaw Polytechnic,theUniversity of Wrocław,Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznańand theUniversity of Technology in Gdańskare among the most prominent.[337]There are three conventionalacademic degreesin Poland –licencjatorinżynier(first cycle),magister(second cycle) anddoktor(third cycle qualification).[338]

Ethnicity

Ethnic structure of Poland by voivodeship according to the censuses of 2002, 2011 and 2021:[339][340][341]

| Census year | 2002 census | 2011 census | 2021 census | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voivodeship | Polish ethnicity | Non-Polish ethnicity | Not reported or no ethnicity | Polish ethnicity (including mixed) | Only non-Polish ethnicity | Not reported or no ethnicity | Polish ethnicity (including mixed) | Only non-Polish ethnicity | Not reported or no ethnicity |

| Lower Silesian | 98.02% | 0.42% | 1.56% | 97.87% | 0.38% | 1.75% | 99.25% | 0.72% | 0.03% |

| Greater Poland | 99.29% | 0.13% | 0.58% | 98.96% | 0.13% | 0.91% | 99.60% | 0.38% | 0.02% |

| Holy Cross | 98.50% | 0.09% | 1.41% | 98.82% | 0.08% | 1.10% | 99.70% | 0.27% | 0.03% |

| Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 98.74% | 0.13% | 1.13% | 98.73% | 0.12% | 1.15% | 99.63% | 0.34% | 0.03% |

| Lesser Poland | 98.72% | 0.26% | 1.02% | 98.22% | 0.24% | 1.54% | 99.50% | 0.47% | 0.03% |

| Lublin | 98.74% | 0.13% | 1.12% | 98.66% | 0.14% | 1.20% | 99.64% | 0.33% | 0.03% |

| Lubusz | 97.72% | 0.33% | 1.95% | 98.26% | 0.31% | 1.43% | 99.43% | 0.54% | 0.03% |

| Łódź | 98.06% | 0.15% | 1.78% | 98.86% | 0.16% | 0.98% | 99.61% | 0.37% | 0.02% |

| Masovian | 96.55% | 0.26% | 3.19% | 98.61% | 0.37% | 1.02% | 99.29% | 0.68% | 0.03% |

| Opole | 81.62% | 12.52% | 5.86% | 88.14% | 9.72% | 2.14% | 95.58% | 4.33% | 0.09% |

| Podlaskie | 93.94% | 4.57% | 1.49% | 95.18% | 2.89% | 1.93% | 98.17% | 1.79% | 0.04% |

| Pomeranian | 97.42% | 0.58% | 2.00% | 97.68% | 0.95% | 1.37% | 98.97% | 1.01% | 0.02% |

| Silesian | 91.99% | 3.93% | 4.08% | 90.65% | 7.78% | 1.57% | 95.49% | 4.48% | 0.03% |

| Subcarpathian | 98.83% | 0.26% | 0.91% | 98.16% | 0.21% | 1.63% | 99.60% | 0.36% | 0.04% |

| Warmian-Masurian | 97.13% | 1.28% | 1.60% | 97.59% | 0.90% | 1.51% | 99.21% | 0.76% | 0.03% |

| West Pomeranian | 98.27% | 0.46% | 1.27% | 98.18% | 0.36% | 1.46% | 99.39% | 0.58% | 0.03% |

| Poland | 96.74% | 1.23% | 2.03% | 97.10% | 1.55% | 1.35% | 98.84% | 1.13% | 0.03% |

Culture

The culture of Poland is closely connected with its intricate 1,000-yearhistory,and forms an important constituent in theWestern civilisation.[342]The Poles take great pride in their national identity which is often associated with the colours white and red, and exuded by the expressionbiało-czerwoni( "whitereds" ).[343]National symbols, chiefly the crownedwhite-tailed eagle,are often visible on clothing, insignia and emblems.[344]The architectural monuments of great importance are protected by theNational Heritage Board of Poland.[345]Over 100 of the country's most significant tangible wonders were enlisted onto theHistoric Monuments Register,[346]with further 17 being recognised byUNESCOas World Heritage Sites.[347]

Holidays and traditions

There are 13 government-approved annual public holidays – New Year on 1 January,Three Kings' Dayon 6 January,Easter SundayandEaster Monday,Labour Dayon 1 May,Constitution Dayon 3 May,Pentecost,Corpus Christi,Feast of the Assumptionon 15 August,All Saints' Dayon 1 November,Independence Dayon 11 November and Christmastide on 25 and 26 December.[348]

Particular traditions and superstitious customs observed in Poland are not found elsewhere in Europe. Though Christmas Eve (Wigilia) is not a public holiday, it remains the most memorable day of the entire year.Treesare decorated on 24 December, hay is placed under the tablecloth to resemble Jesus'manger,Christmas wafers(opłatek) are shared between gathered guests and atwelve-dish meatless supperis served that same evening when thefirst starappears.[349]An empty plate and seat are symbolically left at the table for an unexpected guest.[350]On occasion,carolersjourney around smaller towns with a folkTurońcreature until theLentperiod.[351]

A widely-populardoughnutand sweet pastry feast occurs onFat Thursday,usually 52 days prior to Easter.[352]EggsforHoly Sundayare painted and placed in decoratedbasketsthat are previously blessed by clergymen in churches onEaster Saturday.Easter Monday is celebrated with pagandyngusfestivities, where the youth is engaged in water fights.[353][352]Cemeteries and graves of the deceased are annually visited by family members on All Saints' Day; tombstones are cleaned as a sign of respect and candles are lit to honour the dead on an unprecedented scale.[354]

Music

Artists from Poland, including famous musicians such asFrédéric Chopin,Artur Rubinstein,Ignacy Jan Paderewski,Krzysztof Penderecki,Henryk Wieniawski,Karol Szymanowski,Witold Lutosławski,Stanisław Moniuszkoand traditional, regionalisedfolk composerscreate a lively and diverse music scene, which even recognises its own music genres, such assung poetryanddisco polo.[355]

The origins of Polish music can be traced to the 13th century; manuscripts have been found inStary Sączcontainingpolyphoniccompositions related to the ParisianNotre Dame School.Other early compositions, such as the melody ofBogurodzicaandGod Is Born(a coronationpolonaise tunefor Polish kings by an unknown composer), may also date back to this period, however, the first known notable composer,Nicholas of Radom,lived in the 15th century.Diomedes Cato,a native-born Italian who lived in Kraków, became a renowned lutenist at the court of Sigismund III; he not only imported some of the musical styles from southern Europe but blended them with native folk music.[356]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Polish baroque composers wroteliturgical musicand secular compositions such as concertos andsonatasfor voices or instruments. At the end of the 18th century, Polish classical music evolved into national forms like thepolonaise.Wojciech Bogusławskiis accredited with composing the first Polish national opera, titledKrakowiacy i Górale,which premiered in 1794.[357]

Poland today has an active music scene, with the jazz and metal genres being particularly popular among the contemporary populace. Polish jazz musicians such asKrzysztof Komedacreated a unique style, which was most famous in the 1960s and 1970s and continues to be popular to this day. Poland has also become a major venue for large-scale music festivals, chief among which are thePol'and'Rock Festival,[358]Open'er Festival,Opole FestivalandSopot Festival.[359]

Art

Art in Poland has invariably reflectedEuropeantrends, with Polish painting pivoted onfolklore,Catholic themes,historicismandrealism,but also onImpressionismandromanticism.An important art movement wasYoung Poland,developed in the late 19th century for promotingdecadence,symbolismandArt Nouveau.Since the 20th century Polish documentary art and photography has enjoyed worldwide fame, especially thePolish School of Posters.[360]One of the most distinguished paintings in Poland isLady with an Ermine(1490) byLeonardo da Vinci.[361]

Internationally renowned Polish artists includeJan Matejko(historicism),Jacek Malczewski(symbolism),Stanisław Wyspiański(art nouveau),Henryk Siemiradzki(Romanacademic art),Tamara de Lempicka(art deco), andZdzisław Beksiński(dystopiansurrealism).[362]Several Polish artists and sculptors were also acclaimed representatives ofavant-garde,constructivist,minimalistand contemporary art movements, includingKatarzyna Kobro,Władysław Strzemiński,Magdalena Abakanowicz,Alina Szapocznikow,Igor MitorajandWilhelm Sasnal.

Notable art academies in Poland include theKraków Academy of Fine Arts,Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw,Art Academy of Szczecin,University of Fine Arts in Poznańand theGeppert Academy of Fine Arts in Wrocław.Contemporary works are exhibited atZachęta,Ujazdów,andMOCAKart galleries.[363]

Architecture

Thearchitecture of PolandreflectsEuropean architecturalstyles, with strong historical influences derived fromItaly,Germany,and theLow Countries.[364]Settlements founded onMagdeburg Lawevolved aroundcentral marketplaces(plac,rynek), encircled by a grid orconcentricnetwork of streets forming anold town(stare miasto).[365]Poland's traditional landscape is characterised by ornate churches,city tenementsandtown halls.[366]Cloth hall markets(sukiennice) were once an abundant feature of Polish urban architecture.[367]The mountainous south is known for itsZakopane chalet style,which originated in Poland.[368]

The earliest architectonic trend wasRomanesque(c.11th century), but its traces in the form ofcircular rotundasare scarce.[369]The arrival ofbrick Gothic(c.13th century) defined Poland's most distinguishable medieval style, exuded by the castles ofMalbork,Lidzbark,GniewandKwidzynas well as the cathedrals ofGniezno,Gdańsk,Wrocław,FromborkandKraków.[370]TheRenaissance(16th century) gave rise to Italianate courtyards, defensivepalazzosandmausoleums.[371]Decorativeatticswithpinnaclesandarcadeloggiasare elements ofPolish Mannerism,found inPoznań,LublinandZamość.[372][373]Foreign artisans often came at the expense of kings or nobles, whose palaces were built thereafter in theBaroque,NeoclassicalandRevivaliststyles (17th–19th century).[374]

Primary building materialstimberandred brickwere used extensively in Polish folk architecture,[375]and the concept of afortified churchwas commonplace.[376]Secular structures such asdworekmanor houses,farmsteads,granaries,millsand countryinnsare still present in some regions or in open air museums (skansen).[377]However, traditional construction methods faded in the early-mid 20th century due to urbanisation and the construction offunctionalisthousing estatesandresidential areas.[378]

Literature

Theliterary works of Polandhave traditionally concentrated around the themes of patriotism,spirituality,socialallegoriesand moral narratives.[379]The earliest examples of Polish literature, written inLatin,date to the 12th century.[380]The firstPolishphraseDay ut ia pobrusa, a ti poziwai(officially translated as "Let me, I shall grind, and you take a rest" ) was documented in theBook of Henrykówand reflected the use of aquern-stone.[381]It has been since included inUNESCO's Memory of World Register.[382]The oldest extant manuscripts of fineproseinOld Polishare theHoly Cross Sermonsand theBible of Queen Sophia,[383]andCalendarium cracoviense(1474) is Poland's oldest survivingprint.[384]

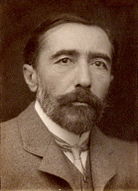

The poetsJan KochanowskiandNicholas Reybecame the firstRenaissanceauthors to write in Polish.[385]Prime literarians of the period includedDantiscus,Modrevius,Goslicius,Sarbieviusand theologianJohn Laski.In theBaroqueera,Jesuit philosophyand local culture greatly influenced the literary techniques ofJan Andrzej Morsztyn(Marinism) andJan Chryzostom Pasek(sarmatianmemoirs).[386]During theEnlightenment,playwrightIgnacy Krasickicomposed the first Polish-languagenovel.[387]Poland's leading 19th-centuryromantic poetswere theThree Bards–Juliusz Słowacki,Zygmunt KrasińskiandAdam Mickiewicz,whose epic poemPan Tadeusz(1834) is a national classic.[388]In the 20th century, the Englishimpressionistand earlymodernistwritings ofJoseph Conradmade him one of the most eminent novelists of all time.[389][390]

Contemporary Polish literature is versatile, with its fantasy genre having been particularly praised.[391]The philosophicalsci-finovelSolarisbyStanisław LemandThe Witcherseries byAndrzej Sapkowskiare celebrated works of world fiction.[392]Poland has sixNobel-Prize winningauthors –Henryk Sienkiewicz(Quo Vadis;1905),Władysław Reymont(The Peasants;1924),Isaac Bashevis Singer(1978),Czesław Miłosz(1980),Wisława Szymborska(1996), andOlga Tokarczuk(2018).[393][394][395]

Cuisine

The cuisine of Poland is eclectic and shares similarities with other regional cuisines. Among the staple or regional dishes arepierogi(filled dumplings),kielbasa(sausage),bigos(hunter's stew),kotlet schabowy(breaded cutlet),gołąbki(cabbage rolls),barszcz(borscht),żurek(soured rye soup),oscypek(smoked cheese), andtomato soup.[396][397]Bagels,a type ofbread roll,also originated in Poland.[398]

Traditional dishes are hearty and abundant in pork, potatoes, eggs, cream, mushrooms, regional herbs, and sauce.[399]Polish food is characteristic for its various kinds ofkluski(soft dumplings),soups,cereals and a variety of breads andopen sandwiches.Salads, includingmizeria(cucumber salad),coleslaw,sauerkraut,carrot andseared beets,are common. Meals conclude with a dessert such assernik(cheesecake),makowiec(poppy seed roll), ornapoleonka(mille-feuille) cream pie.[400]

Traditional alcoholic beverages include honeymead,widespread since the 13th century,beer,wine andvodka.[401]The world's first written mention of vodka originates from Poland.[402]The most popular alcoholic drinks at present are beer and wine which took over from vodka more popular in the years 1980–1998.[403]Grodziskie,sometimes referred to as "Polish Champagne", is an example of a historical beer style from Poland.[404]Tea remains common in Polish society since the 19th century, whilst coffee is drunk widely since the 18th century.[405]

Fashion and design

Several Polish designers and stylists left a legacy of beauty inventions and cosmetics; includingHelena RubinsteinandMaksymilian Faktorowicz,who created a line of cosmetics company in California known asMax Factorand formulated the term "make-up" which is now widely used as an alternative for describing cosmetics.[406]Faktorowicz is also credited with inventing moderneyelash extensions.[407][408]As of 2020, Poland possesses the sixth-largest cosmetic market in Europe.Inglot Cosmeticsis the country's largest beauty products manufacturer,[409]and the retail storeReservedis the country's most successful clothing store chain.[410]

Historically, fashion has been an important aspect of Poland's national consciousness orcultural manifestation,and the country developed its own style known asSarmatismat the turn of the 17th century.[411]The national dress and etiquette of Poland also reached the court atVersailles,where French dresses inspired by Polish garments includedrobe à la polonaiseand thewitzchoura.The scope of influence also entailed furniture; rococoPolish bedswithcanopiesbecame fashionable in French châteaus.[412]Sarmatism eventually faded in the wake of the 18th century.[411]

Cinema

Thecinema of Polandtraces its origins to 1894, when inventorKazimierz Prószyńskipatented thePleographand subsequently theAeroscope,the first successful hand-held operated film camera.[413][414]In 1897,Jan Szczepanikconstructed theTelectroscope,a prototype of television transmitting images and sounds.[413]They are both recognised as pioneers ofcinematography.[413]Poland has also produced influential directors, film producers and actors, many of whom were active inHollywood,chieflyRoman Polański,Andrzej Wajda,Pola Negri,Samuel Goldwyn,theWarner brothers,Max Fleischer,Agnieszka Holland,Krzysztof ZanussiandKrzysztof Kieślowski.[415]

Thethemescommonly explored in Polish cinema includehistory,drama,war, culture and black realism (film noir).[413][414]In the 21st-century, two Polish productions won theAcademy Awards–The Pianist(2002) by Roman Polański andIda(2013) byPaweł Pawlikowski.[414]Polish cinematography also created many well-received comedies. The most known of them were made byStanisław BarejaandJuliusz Machulski.

Media

According to theEurobarometer Report(2015), 78 percent of Poles watch thetelevisiondaily.[416]In 2020, 79 percent of the population read the news more than once a day, placing it second behind Sweden.[417]Poland has a number of major domestic media outlets, chiefly thepublic broadcastingcorporationTVP,free-to-airchannelsTVNandPolsatas well as 24-hour news channelsTVP Info,TVN 24andPolsat News.[418]Public television extends its operations to genre-specific programmes such asTVP Sport,TVP Historia,TVP Kultura,TVP Rozrywka,TVP Seriale andTVP Polonia,the latter a state-run channel dedicated to the transmission of Polish-language telecasts for thePolish diaspora.In 2020, the most popular types of newspapers weretabloidsand socio-political news dailies.[416]

Poland is a major European hub for video game developers and among the most successful companies areCD Projekt,Techland,The Farm 51,CI GamesandPeople Can Fly.[419]Some of the popular video games developed in Poland includeThe Witchertrilogy andCyberpunk 2077.[419]The Polish city ofKatowicealso hostsIntel Extreme Masters,one of the biggestesportsevents in the world.[419]

Sports