Taenia solium

| Taenia solium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scolex (head) ofTaenia solium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Cestoda |

| Order: | Cyclophyllidea |

| Family: | Taeniidae |

| Genus: | Taenia |

| Species: | T. solium

|

| Binomial name | |

| Taenia solium | |

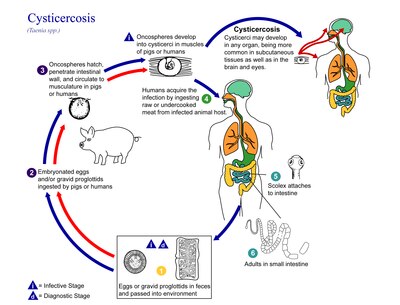

Taenia solium,thepork tapeworm,belongs to thecyclophyllidcestodefamilyTaeniidae.It is found throughout the world and is most common in countries whereporkis eaten. It is atapewormthat uses humans as itsdefinitive hostandpigsas theintermediate or secondary hosts.It is transmitted to pigs throughhuman fecesthat contain the parasite eggs and contaminate their fodder. Pigs ingest theeggs,which develop into larvae, then intooncospheres,and ultimately into infective tapeworm cysts, called cysticercus. Humans acquire the cysts through consumption of uncooked or under-cooked pork and the cysts grow into adult worms in thesmall intestine.

There are two forms of human infection. One is "primary hosting", called taeniasis, and is due to eating under-cooked pork that contains the cysts and results in adult worms in the intestines. This form generally iswithout symptoms;the infected person does not know they have tapeworms. This form is easily treated with anthelmintic medications which eliminate the tapeworm. The other form, "secondary hosting", called cysticercosis, is due to eating food, or drinking water, contaminated with faeces from someone infected by the adult worms, thus ingesting the tapeworm eggs, instead of the cysts. The eggs go on to developcystsprimarily in the muscles, and usually with no symptoms. However some people have obvious symptoms, the most harmful and chronic form of which is when the cysts formin the brain.Treatment of this form is more difficult but possible.

The adult worm has a flat, ribbon-like body which is white and measures 2 to 3 metres (6' to 10') long, or more. Its tiny attachment, thescolex,containssuckersand arostellumas organs of attachment that attach to the wall of thesmall intestine.Themain body,consists of a chain of segments known asproglottids.Each proglottid is a little more than a self-sustainable, very lightly ingestive, self-containedreproductive unitsince tapeworms arehermaphrodites.

Human primary hosting is best diagnosed by microscopy of eggs in faeces, often triggered by spotting shed segments. In secondary hosting, imaging techniques such ascomputed tomographyandnuclear magnetic resonanceare often employed. Blood samples can also be tested usingantibody reactionofenzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

T. soliumdeeply affects developing countries, especially in rural settings where pigs roam free,[1]as clinical manifestations are highly dependent on the number, size, and location of the parasites as well as the host's immune and inflammatory response.[2]

Description

[edit]AdultT. soliumis atriploblasticacoelomate,having no body cavity. It is normally 2 to 3 metres (6' to 10') in length, but can become much larger, sometimes over 8 metres (30') long. It is white in colour and flattened into a ribbon-like body. The anterior end is a knob-like attachment organ (sometimes mistakenly referred to as a "head" ) called ascolex,1 mm in diameter. The scolex bears four radially arrangedsuckersthat surround the rostellum. These are the organs of adhesive attachment to the intestinal wall of the host. The rostellum is armed with two rows ofproteinaceous[3][4]spiny hooks.[5]Its 22 to 32 rostellar hooks can be differentiated into short (130 μm) and long (180 μm) types.[6][7]

After a short neck is the elongated body, the strobila. The entire body is covered by a covering called ategument,which is an absorptive layer consisting of a mat of minute specialisedmicrovillicalledmicrotriches.The strobila is divided into segments called proglottids, 800 to 900 in number. Body growth starts from the neck region, so the oldest proglottids are at the posterior end. Thus, the three distinct proglottids are immature proglottids towards the neck, mature proglottids in the middle, andgravidproglottids at the posterior end. Ahermaphroditicspecies, each mature proglottid contains a set of male and female reproductive systems. The numeroustestesand a bilobedovaryopen into a common genital pore. The oldest gravid proglottids are full of fertilised eggs,[8][9][10][11]Each fertilised egg is spherical and measures 35 to 42 μm in diameter.[7]

If released early enough in the digestive tract and not passed, fertilised eggs can mature using upper tract digestive enzymes and the tiny larvae migrate to formcysticerciin humans. These have three morphologically distinct types.[12]The common one is the ordinary "cellulose"cysticercus, which has a fluid-filledbladder0.5 to 1.5 cm (¼ "to ½" ) in length and an invaginatedscolex.The intermediate form has a scolex. The "racemose" has no evident scolex, but is believed to be larger. They can be 20 cm (8 ") in length and have 60 ml (2 fl. oz.) of fluid, and 13% of patients with neurocysticercosis can have all three types in the brain.[13][14]

-

Taenia soliumadult

-

Taenia soliumscolex (x400)

-

Egg ofT. solium

Life cycle

[edit]

The life cycle ofT. soliumis indirect as it passes through pigs, as intermediate hosts, into humans, as definitive hosts. In humans the infection can be relatively short or long lasting, and in the latter case if reaching the brain can last for life. From humans, the eggs are released in the environment where they await ingestion by another host. In the secondary host, the eggs develop into oncospheres which bore through the intestinal wall and migrate to other parts of the body where the cysticerci form. The cysticerci can survive for several years in the animal.[15]

Definitive host

[edit]Humans are colonised by the larval stage, the cysticercus, from undercooked pork or other meat. Each microscopic cysticercus is oval in shape, containing an inverted scolex (specifically "protoscolex" ), which everts once the organism is inside the small intestine. This process ofevaginationis stimulated bybile juiceanddigestive enzymes(of the host). Then, the protoscolex lodges in the host's upper intestine by using its crowned hooks and 4 suckers to enter the intestinal mucosa. Then, the scolex is fixed into the intestine by having the suckers attached to the villi and hooks extended. It grows in size using nutrients from the surroundings. Its strobila lengthens as new proglottids are formed at the foot of the neck. In 10–12 weeks after initial colonisation, it is an adult worm.[16]The exact life span of an adult worm is not determined; however, evidences from an outbreak among British military in the 1930s indicate that they can survive for 2 to 5 years in humans.[17][1]

As a hermaphrodite, it reproduces byself-fertilisation,orcross-fertilisationifgametesare exchanged between two different proglottids.Spermatozoafuse with theovain the fertilisation duct, where thezygotesare produced. The zygote undergoesholoblasticand unequalcleavageresulting in three cell types, small, medium and large (micromeres, mesomeres, megameres). Megameres develop into a syncytial layer, the outer embryonic membrane; mesomeres into the radially striated inner embryonic membrane or embryophore; micromeres become themorula.The morula transforms into a six-hooked embryo known as anoncosphere,or hexacanth ( "six hooked" ) larva. A gravid proglottid can contain more than 50,000 embryonated eggs. Gravid proglottids often rupture in the intestine, liberating the oncospheres in faeces. Intact gravid proglottids are shed off in groups of four or five. The free eggs and detached proglottids are spread through the host's defecation (peristalsis). Oncospheres can survive in the environment for up to two months.[9][18]

Intermediate host

[edit]Pigs are the principal intermediate hosts that ingest the eggs in traces of human faeces, mainly from vegetation contaminated with it such as from water bearing traces of it. The embryonated eggs enter intestine where theyhatchinto motile oncospheres. The embryonic and basement membranes are removed by the host's digestive enzymes (particularlypepsin). Then the free oncospheres attach on the intestinal wall using their hooks. With the help of digestive enzymes from the penetration glands, they penetrate theintestinal mucosato enterbloodandlymphatic vessels.They move along the generalcirculatory systemto various organs, and large numbers are cleared in theliver.The surviving oncospheres preferentially migrate tostriated muscles,as well as thebrain,liver, and other tissues, where they settle to formcysts— cysticerci. A single cysticercus is spherical, measuring 1–2 cm (about ½ ") in diameter, and contains an invaginated protoscolex. The central space is filled with fluid like abladder,hence it is also called bladder worm. Cysticerci are usually formed within 70 days and may continue to grow for a year.[19]

Humans are also accidental secondary hosts when they are colonised by embryonated eggs, either by auto-colonisation or ingestion of contaminated food. As in pigs, the oncospheres hatch and enter blood circulation. When they settle to form cysts, clinical symptoms ofcysticercosisappear. The cysticercus is often called the metacestode.[20]

Diseases

[edit]Signs and symptoms

[edit]Taeniasis

[edit]Taeniasis is infection in the intestines by the adultT. solium.It generally has mild ornon-specific symptoms.This may include abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea and constipation. Such symptoms will arise when the tapeworm has fully developed in the intestine, this would be around eight weeks after the contraction (ingestion of meat containing cysticerci).[21]

These symptoms could continue until the tapeworm dies from the course of treatment but otherwise could continue for many years, as long as the worm lives. If untreated it is common that the infections withT. soliumlast for approximately 2–3 years. It is possible that infected people may show no symptoms for years.[21]

Cysticercosis

[edit]Ingestion ofT. soliumeggs or egg-containing proglottids which rupture within the host intestines results in the development and subsequent migration oflarvaeinto host tissue to cause cysticercosis. In pigs, there are not normally pathological lesions as they easily develop immunity.[22]But in humans, infection with the eggs causes serious medical conditions. This is becauseT. soliumcysticerci have a predilection for the brain. In symptomatic cases, a wide spectrum of symptoms may be expressed, including headaches, dizziness, and seizures. Brain infection by the cysticerci is called neurocysticercosis and is the leading cause of seizures worldwide.[1][23]

In more severe cases,dementiaorhypertensioncan occur due to perturbation of the normal circulation ofcerebrospinal fluid.(Any increase in intracranial pressure will result in a corresponding increase inarterial blood pressure,as the body seeks to maintain circulation to the brain.) The severity of cysticercosis depends on location, size and number of parasite larvae in tissues, as well as the hostimmune response.Other symptoms include sensory deficits, involuntary movements, and brain system dysfunction. In children,ocularcysts are more common than in other parts of the body.[8]

In many cases, cysticercosis in the brain can lead toepilepsy,seizures,lesionsin the brain,blindness,tumour-like growths, and loweosinophillevels. It is the cause of major neurological problems, such ashydrocephalus,paraplegy,meningitis,convulsions,and even death.[24]

Diagnosis

[edit]Stool testscommonly includemicrobiology testing– the microscopic examination of stools after concentration aims to determine the amount of eggs. Specificity is extremely high for someone with training but sensitivity is quite low because the high variation in the number of eggs in small amounts of sample.[25]

Stool tapeworm antigen detection:UsingELISAincreases the sensitivity of the diagnosis. The downside of this tool is it has high costs, an ELISA reader and reagents are required and trained operators are needed.[25]A studies using Coproantigen (CoAg) ELISA methods are considered very sensitive but currently only genus specific.[26]A 2020 study in Ag-ELISA test onTaenia soliumcystercicosis in infected pigs and showed 82.7% sensitivity and 86.3% specificity. The study concluded that the test is more reliable in ruling out T. solium cystercosis versus confirmation.[citation needed]

StoolPCR:This method can provide a species-specific diagnosis when proglottid material is taken from the stool. This method requires specific facilities, equipment and trained individuals to run the tests. This method has not yet been tested in controlled field trials.[25]

Serum antibody tests:usingimmunoblotand ELISA, tape-worm specific circulating antibodies have been detected. The assays for these tests have both a high sensitivity and specificity.[25]A 2018 study of two commercially available kits showed low sensitivity with patients diagnose with NCC (neurocysticercosis) especially with calcified NCC versus patients with cystic hydatid disease.[27]Current standard for serologic diagnosis of NCC is the lentil lectin-bound glycoproteins/enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (LLGP-EITB).[28]

Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment remain difficult for endemic countries, most of them developing with limited resources.[29]Many developing countries diagnosed clinically with imaging.[citation needed]

Prevention

[edit]The best way to avoid getting tapeworms is to not eat undercooked pork or vegetables contaminated with faeces. Moreover, a high level of sanitation and prevention of faecal contamination of pig feeds also plays a major role in prevention. Infection can be prevented with proper disposal of human faeces around pigs, cooking meat thoroughly or freezing the meat at −10°C (14°F) for 5 days. For human cysticercosis, dirty hands are attributed to be the primary cause, and especially common among food handlers.[19]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment of cysticercosis must be carefully monitored forinflammatory reactionsto the dying worms, especially if they are located in the brain.Albendazoleis commonly given (along withglucocorticoidsto reduce the inflammation). In selected cases, surgery may be required to remove the cysts.[30]

In neurocysticercosis, most patients under cysticidal therapy will have significant improvement in seizure control.[31]A combination ofpraziquanteland albendazole is more effective in treating neurocystercosis.[32]A 2014 double blind randomized control study showed increased parasiticidal effect with albendazole plus praziquantel.[33]

A vaccine to prevent cysticercosis in pigs has been studied. The life-cycle of the parasite can be terminated in their intermediate host, pigs, thereby preventing further human infection. The large scale use of this vaccine, however, is still under consideration.[34][35]

During the 1940s, the preferred treatment was oleoresin ofaspidium,which would be introduced into the duodenum via aRehfuss tube.[36]

Epidemiology

[edit]T. soliumis found worldwide, but its two distinctive forms rely on eating undercooked pork or on ingesting faeces-contaminated water or food (respectively). Because pig meat is the intermediate source of the intestinal parasite, rotation of the fulllife cycleoccurs in regions where humans live in close contact with pigs and eat undercooked pork. However, humans can also act as secondary hosts, which is a more pathological, harmful stage triggered by oral contamination. High prevalences are reported among many places with poorer than average water hygiene or even mildly contaminated water especially with a pork-eating heritage such as Latin America, West Africa, Russia, India, Manchuria, and Southeast Asia.[37]In Europe it is most common in pockets ofSlavic countriesand among global travelers taking inadequate precautions in eating pork especially.[10][38]

The secondary host form, human cysticercosis, predominates in areas where poor hygiene allows for mild fecal contamination of food, soil, or water supplies. Rates in the United States have shown immigrants from Mexico, Central and South America, and Southeast Asia bear the brunt of cases of cysticercosis caused by the ingestion of microscopic, long-lasting and hardy tapeworm eggs.[39]For example, in 1990 and 1991 four unrelated members of anOrthodox Jewishcommunity inNew York Citydeveloped recurrent seizures and brain lesions, which were found to have been caused byT. solium.All had housekeepers from Mexico, some of whom were suspected to be the source of the infections.[40][41]Rates ofT. soliumcysticercosis in West Africa are not affected by any religion.[42]

Neurocystiscercosis is noted at around one-third of all epilepsy cases in many developing countries.[43]Neurological morbidity and mortality remain high in lower-income countries and high amongst developed countries with high rates of migration. Global prevalence rates remain largely unknown as screening tools, immunological, molecular tests, and neuroimaging are not usually available in many endemic areas.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcGarcia, H. H.; Rodriguez, S.; Friedland, J. S.; for The Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru (2014)."Immunology ofTaenia soliumtaeniasis and human cysticercosis ".Parasite Immunology.36(8): 388–396.doi:10.1111/pim.12126.PMC5761726.PMID24962350.

- ^Gonzales I, Rivera JT, Garcia HH (March 2016). "Pathogenesis ofTaenia soliumtaeniasis and cysticercosis ".Parasite Immunol.38(3): 136–46.doi:10.1111/pim.12307.PMID26824681.

- ^Crusz Hilary (1947). "The early development of the rostellum ofCysticercus fasciolarisRud., and the chemical nature of its hooks ".The Journal of Parasitology.33(2): 87–98.doi:10.2307/3273530.JSTOR3273530.PMID20294080.

- ^Mount P. M. (1970). "Histogenesis of the rostellar hooks ofTaenia crassiceps(Zeder, 1800) (Cestoda) ".The Journal of Parasitology.56(5): 947–961.doi:10.2307/3277513.JSTOR3277513.PMID5504533.

- ^Sjaastad, Oyestein V.; Hove, Knut; Sand, Olav (2010).Physiology of Domestic Animals(2nd ed.). Oslo: Scandinavian Veterinary Press.ISBN978-82-91743-07-3.

- ^Flisser, Ana; Viniegra, Ana-Elena; Aguilar-Vega, Laura; Garza-Rodriguez, Adriana; Maravilla, Pablo; Avila, Guillermina (2004). "Portrait of Human Tapeworms".The Journal of Parasitology.90(4): 914–6.doi:10.1645/GE-3354CC.JSTOR3286360.PMID15357104.S2CID35124422.

- ^abCheng, Thomas C. (1986).General Parasitology(2 ed.). Oxford: Elsevier Science. pp. 413–4.ISBN978-0-323-14010-2.OCLC843201842.

- ^abPawlowski, Z.S.; Prabhakar, Sudesh (2002). "Taenia solium:basic biology and transmission ". In Gagandeep Singh, Sudesh Prabhakar (ed.).Taenia soliumCysticercosis from Basic to Clinical Science.Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CABI. pp. 1–14.ISBN978-0-85199-839-8.

- ^abBurton J. Bogitsh; Clint E. Carter (2013).Human Parasitology(4th ed.). Amsterdam: Academic Press. pp. 241–4.ISBN978-0-12-415915-0.

- ^abGutierrez, Yezid (2000).Diagnostic Pathology of Parasitic Infections with Clinical Correlations(2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 635–652.ISBN978-0-19-512143-8.

- ^Willms, Kaethe (2008). "Morphology and Biochemistry of the Pork Tapeworm,Taenia solium".Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry.8(5): 375–382.doi:10.2174/156802608783790875.PMID18393900.

- ^Rabiela, MT; Rivas, A; Flisser, A (November 1989). "Morphological types ofTaenia soliumcysticerci ".Parasitology Today.5(11): 357–9.doi:10.1016/0169-4758(89)90111-7.PMID15463154.

- ^Modi, Manish; Lal, Vivek; Prabhakar, Sudesh; Bhardwaj, Amit; Sehgal, Rakesh; Sharma, Sudhir (2013)."Reversible dementia as a presenting manifestation of racemose neurocysticercosis".Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology.16(1): 88–90.doi:10.4103/0972-2327.107706.PMC3644790.PMID23661971.

- ^McClugage, SamuelG; Lee, RachaelA; Camins, BernardC; Mercado-Acosta, JuanJ; Rodriguez, Martin; Riley, KristenO (2017)."Treatment of racemose neurocysticercosis".Surgical Neurology International.8(1): 168.doi:10.4103/sni.sni_157_17.PMC5551286.PMID28840072.

- ^Biology. (2013, January 10). Retrieved fromhttps:// cdc.gov/parasites/taeniasis/biology.html

- ^Mehlhorn, Heinz (2016), "Taenia solium",in Mehlhorn, Heinz (ed.),Encyclopedia of Parasitology,Springer, pp. 2614–21,doi:10.1007/978-3-662-43978-4_3093,ISBN978-3-662-43977-7

- ^Dixon, H.B.F.; Hargreaves, W.H. (1944)."Cysticercosis (Taenia solium): a further ten years' clinical study, covering 284 cases ".QJM: An International Journal of Medicine.13(4): 107–122.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.qjmed.a066444.

- ^Mayta, Holger (2009).Cloning and Characterization of Two Novel Taenia Solium Antigenic Proteins and Applicability to the Diagnosis and Control of Taeniasis/cysticercosis.pp. 4–12.ISBN978-0-549-93899-6.

- ^abHector H. Garcia; Oscar H. Del Brutto (2014). "Taenia solium:Biological Characteristics and Life Cycle ".Cysticercosis of the Human Nervous System(1., 2014 ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag Berlin and Heidelberg GmbH & Co. KG. pp. 11–21.ISBN978-3-642-39021-0.

- ^Coral-Almeida, Marco; Gabriël, Sarah; Abatih, Emmanuel Nji; Praet, Nicolas; Benitez, Washington; Dorny, Pierre (2015). Torgerson, Paul Robert (ed.)."Taenia soliumHuman Cysticercosis: A Systematic Review of Sero-epidemiological Data from Endemic Zones around the World ".PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.9(7): e0003919.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003919.PMC4493064.PMID26147942.

- ^ab"Taeniasis/Cysticercosis".who.int.Retrieved2019-04-02.

- ^de Aluja, A.S.; Villalobos, A.N.M.; Plancarte, A.; Rodarte, L.F.; Hernandez, M.; Zamora, C.; Sciutto, E. (1999). "Taenia soliumcysticercosis: immunity in pigs induced by primary infection ".Veterinary Parasitology.81(2): 129–135.doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(98)00234-9.PMID10030755.

- ^DeGiorgio, Christopher M.; Medina, Marco T.; Durón, Reyna; Zee, Chi; Escueta, Susan Pietsch (2004)."Neurocysticercosis".Epilepsy Currents.4(3): 107–111.doi:10.1111/j.1535-7597.2004.43008.x.PMC1176337.PMID16059465.

- ^Flisser, A.; Avila G; Maravilla P; Mendlovic F; León-Cabrera S; Cruz-Rivera M; Garza A; Gómez B; Aguilar L; Terán N; Velasco S; Benítez M; Jimenez-Gonzalez DE (2010). "Taenia solium:current understanding of laboratory animal models of taeniosis ".Parasitology.137(3): 347–57.doi:10.1017/S0031182010000272.PMID20188011.S2CID25698465.

- ^abcdGilman, Robert H; Gonzalez, Armando E; Llanos-Zavalaga, Fernando; Tsang, Victor C W; Garcia, Hector H (September 2012)."Prevention and control ofTaenia soliumtaeniasis/cysticercosis in Peru ".Pathogens and Global Health.106(5): 312–8.doi:10.1179/2047773212Y.0000000045.PMC4005116.PMID23265557.

- ^Guezala MC, Rodriguez S, Zamora H, Garcia HH, Gonzalez AE, Tembo A, Allan JC, Craig PS (September 2009). "Development of a species-specific coproantigen ELISA for humanTaenia soliumtaeniasis ".Am J Trop Med Hyg.81(3): 433–7.doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2009.81.433.PMID19706909.

- ^Garcia HH, Castillo Y, Gonzales I, Bustos JA, Saavedra H, Jacob L, Del Brutto OH, Wilkins PP, Gonzalez AE, Gilman RH (January 2018)."Low sensitivity and frequent cross-reactions in commercially available antibody detection ELISA assays forTaenia soliumcysticercosis ".Trop Med Int Health.23(1): 101–5.doi:10.1111/tmi.13010.PMC5760338.PMID29160912.

- ^Hernández-González A, Noh J, Perteguer MJ, Gárate T, Handali S (May 2017)."Comparison of T24H-his, GST-T24H and GST-Ts8B2 recombinant antigens in western blot, ELISA and multiplex bead-based assay for diagnosis of neurocysticercosis".Parasit Vectors.10(1): 237.doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2160-2.PMC5433036.PMID28506245.

- ^Carpio A, Fleury A, Kelvin EA, Romo ML, Abraham R, Tellez-Zenteno J (October 2018). "New guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of neurocysticercosis: a difficult proposal for patients in endemic countries".Expert Rev Neurother.18(10): 743–7.doi:10.1080/14737175.2018.1518133.PMID30185077.

- ^Nash, Theodore E.; Mahanty, Siddhartha; Garcia, Hector H. (2011)."Corticosteroid use in neurocysticercosis".Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics.11(8): 1175–83.doi:10.1586/ern.11.86.PMC3721198.PMID21797658.

- ^Santos IC, Kobayashi E, Cardoso TM, Guerreiro CA, Cendes F (December 2000). "Cysticidal therapy: impact on seizure control in epilepsy associated with neurocysticercosis".Arq Neuropsiquiatr.58(4): 1014–20.doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2000000600006.PMID11105066.

- ^Garcia HH, Lescano AG, Gonzales I, Bustos JA, Pretell EJ, Horton J, Saavedra H, Gonzalez AE, Gilman RH (June 2016)."Cysticidal Efficacy of Combined Treatment With Praziquantel and Albendazole for Parenchymal Brain Cysticercosis".Clin Infect Dis.62(11): 1375–9.doi:10.1093/cid/ciw134.PMC4872290.PMID26984901.

- ^Garcia HH, Gonzales I, Lescano AG, Bustos JA, Zimic M, Escalante D, Saavedra H, Gavidia M, Rodriguez L, Najar E, Umeres H, Pretell EJ (August 2014)."Efficacy of combined antiparasitic therapy with praziquantel and albendazole for neurocysticercosis: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial".Lancet Infect Dis.14(8): 687–695.doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70779-0.PMC4157934.PMID24999157.

- ^Lightowlers, Marshall W.; Donadeu, Meritxell; Gauci, Charles G.; Colston, Angela; Kushwaha, Peetambar; Singh, Dinesh Kumar; Subedi, Suyog; Sah, Keshav; Poudel, Ishab (25 February 2019)."Implementation of a practical and effective pilot intervention against transmission ofTaenia soliumby pigs in the Banke district of Nepal ".PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.13(2): e0006838.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006838.PMC6405169.PMID30802248.

- ^Garcia HH, Lescano AG, Lanchote VL, Pretell EJ, Gonzales I, Bustos JA, Takayanagui OM, Bonato PS, Horton J, Saavedra H, Gonzalez AE, Gilman RH (July 2011)."Pharmacokinetics of combined treatment with praziquantel and albendazole in neurocysticercosis".Br J Clin Pharmacol.72(1): 77–84.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03945.x.PMC3141188.PMID21332573.

- ^"Clinical Aspects and Treatment of the More Common Intestinal Parasites of Man (TB-33)".Veterans Administration Technical Bulletin 1946 & 1947.10:1–14. 1948.

- ^M.M. Reeder; P.E.S. Palmer (2001).Imaging of Tropical Diseases: With Epidemiological, Pathological, and Clinical Correlation(2nd ed.). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag. pp. 641–2.ISBN978-3-540-56028-9– via books.google.

- ^Hansen, NJ; Hagelskjaer, LH; Christensen, T (1992). "Neurocysticercosis: a short review and presentation of a Scandinavian case".Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases.24(3): 255–62.doi:10.3109/00365549209061330.PMID1509231.

- ^Flisser A. (May 1988). "Neurocysticercosis in Mexico".Parasitology Today.4(5): 131–7.doi:10.1016/0169-4758(88)90187-1.PMID15463066.

- ^Dworkin, Mark S. (2010).Outbreak Investigations Around the World: Case Studies in Infectious Disease.Jones and Bartlett. pp. 192–6.ISBN978-0-7637-5143-2.RetrievedAugust 9,2011.

- ^Schantz; Moore, Anne C.; et al. (September 3, 1992)."Neurocysticercosis in an Orthodox Jewish Community in New York City".New England Journal of Medicine.327(10): 692–5.doi:10.1056/NEJM199209033271004.PMID1495521.

- ^Melki, Jihen; Koffi, Eugène; Boka, Marcel; Touré, André; Soumahoro, Man-Koumba; Jambou, Ronan (2018)."Taenia soliumcysticercosis in West Africa: status update ".Parasite.25:49.doi:10.1051/parasite/2018048.PMC6144651.PMID30230445.

- ^Garcia HH, O'Neal SE, Noh J, Handali S (September 2018)."Laboratory Diagnosis of Neurocysticercosis (Taenia solium) ".J Clin Microbiol.56(9).doi:10.1128/JCM.00424-18.PMC6113464.PMID29875195.

- ^Carpio A, Fleury A, Romo ML, Abraham R (April 2018). "Neurocysticercosis: the good, the bad, and the missing".Expert Rev Neurother.18(4): 289–301.doi:10.1080/14737175.2018.1451328.PMID29521117.