Prague

Prague

Praha(Czech) | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: City of a Hundred Spires | |

| Mottoes: | |

| |

| Coordinates:50°05′15″N14°25′17″E/ 50.08750°N 14.42139°E | |

| Country | |

| Founded | 8th century |

| Government | |

| •Mayor | Bohuslav Svoboda(ODS) |

| Area | |

| •Capital city | 496.21 km2(191.59 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 298 km2(115 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 11,425 km2(4,411 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 399 m (1,309 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 172 m (564 ft) |

| Population (2024-01-01)[5] | |

| •Capital city | 1,384,732 |

| • Density | 2,800/km2(7,200/sq mi) |

| •Metro | 2,267,817[4] |

| • Metro density | 237/km2(610/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Praguer, Pragueite |

| GDP | |

| •Capital city | €78.414 billion (2022) |

| • Metro | €109.990 billion (2022) |

| • Per capita (city) | €59,404 (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Postal codes | 100 00 – 199 00 |

| ISO 3166 code | CZ-10 |

| Vehicle registration | A, AA – AZ |

| HDI(2021) | 0.960[8]–very high·1st |

| Website | praha.eu |

Prague(/ˈprɑːɡ/PRAHG;Czech:Praha[ˈpraɦa])[a]is the capital andlargest cityof theCzech Republic[9]and the historical capital ofBohemia.Situated on theVltavariver, Prague is home to about 1.4 million people. The city has atemperateoceanic climate,with relatively warm summers and chilly winters.

Prague is a political, cultural, and economic hub ofCentral Europe,with a rich history andRomanesque,Gothic,RenaissanceandBaroquearchitectures. It was the capital of theKingdom of Bohemiaand residence of severalHoly Roman Emperors,most notablyCharles IV(r. 1346–1378) andRudolf II(r. 1575–1611).[9]

It was an important city to theHabsburg monarchyandAustria-Hungary.The city played major roles in theBohemianand theProtestant Reformations,theThirty Years' Warand in 20th-century history as the capital ofCzechoslovakiabetween the World Wars and the post-warCommunist era.[10]

Prague is home to a number of well-known cultural attractions includingPrague Castle,Charles Bridge,Old Town Squarewith thePrague astronomical clock,theJewish Quarter,Petřínhill andVyšehrad.Since 1992, the historic center of Prague has been included in theUNESCOlist ofWorld Heritage Sites.

The city has more than ten major museums, along with numerous theatres, galleries, cinemas, and other historical exhibits. An extensive modern public transportation system connects the city. It is home to a wide range of public and private schools, includingCharles Universityin Prague, the oldest university in Central Europe.

Prague is classified as an "Alpha-"global cityaccording toGaWCstudies.[11]In 2019, the city was ranked as 69th most livable city in the world by Mercer.[12]In the same year, the PICSA Index ranked the city as 13th most livable city in the world.[13]Its rich history makes it a popular tourist destination and as of 2017, the city receives more than 8.5 million international visitors annually. In 2017, Prague was listed as the fifth most visited European city afterLondon,Paris,Rome,andIstanbul.[14]

Etymology and names

[edit]The Czech name Praha is derived from an oldSlavicword,práh,which means "ford"or"rapid",referring to the city's origin at a crossing point of the Vltava river.[15]

Another view to the origin of the name is also related to the Czech wordpráh(with the meaning of athreshold) and a legendary etymology connects the name of the city with princessLibuše,prophetess and a wife of the mythical founder of thePřemyslid dynasty.She is said to have ordered the city "to be built where a man hews a threshold of his house". The Czechpráhmight thus be understood to refer to rapids or fords in the river, the edge of which could have acted as a means of fording the river – thus providing a "threshold" to the castle.

Another derivation of the namePrahais suggested fromna prazě,the original term for theshalehillside rock upon which the original castle was built. At that time, the castle was surrounded by forests, covering the nine hills of the future city – theOld Townon the opposite side of the river, as well as theLesser Townbeneath the existing castle, appeared only later.[16]

The English spelling of the city's name is borrowed fromFrench.In the 19th and early 20th centuries it was pronounced in English to rhyme with "vague": it was so pronounced byLady Diana Cooper(born 1892) onDesert Island Discsin 1969,[17]and it is written to rhyme with "vague" in a verse ofThe Beleaguered CitybyLongfellow(1839) and also in the limerickThere was an Old Lady of PraguebyEdward Lear(1846).

Prague is also called the"City of a HundredSpires",based on a count by 19th century mathematicianBernard Bolzano;today's count is estimated by the Prague Information Service at 500.[18]Nicknames for Prague have also included: the Golden City, the Mother of Cities and the Heart of Europe.[19]

The local Jewish community, which belongs to one of the oldest continuously existing in the world, have described the city asעיר ואם בישראלIr va-em be-yisrael,"The city and mother in Israel".[citation needed]

History

[edit]Prague has grown from a settlement stretching fromPrague Castlein the north to the fort ofVyšehradin the south, to become the capital of a modern European country.

Early history

[edit]

The region was settled as early as thePaleolithicage.[20]Jewish chroniclerDavid Solomon Ganz,citingCyriacus Spangenberg,claimed that the city was founded as Boihaem inc. 1306BCby an ancient king, Boyya.[21]

Around the fifth and fourth century BC, aCeltictribe appeared in the area, later establishing settlements, including the largest CelticoppiduminBohemia,Závist, in a present-day south suburbZbraslavin Prague, and naming the region of Bohemia, which means "home of the Boii people".[20][22]In the last century BC, the Celts were slowly driven away byGermanic tribes(Marcomanni,Quadi,Lombardsand possibly theSuebi), leading some to place the seat of theMarcomanniking,Maroboduus,in Závist.[23][21]Around the area where present-day Prague stands, the 2nd century map drawn by Roman geographerPtolemaiosmentioned a Germanic city calledCasurgis.[24]

In the late 5th century AD, during the greatMigration Periodfollowing the collapse of theWestern Roman Empire,the Germanic tribes living in Bohemia moved westwards and, probably in the 6th century, theSlavic tribessettled the Central Bohemian Region. In the following three centuries, theCzech tribesbuilt several fortified settlements in the area, most notably in theŠárka valley,ButoviceandLevý Hradec.[20]

The construction of what came to be known asPrague Castlebegan near the end of the 9th century, expanding a fortified settlement that had existed on the site since the year 800.[25]The first masonry under Prague Castle dates from the year 885 at the latest.[26]The other prominent Prague fort, the Přemyslid fortVyšehrad,was founded in the 10th century, some 70 years later than Prague Castle.[27]Prague Castle is dominated by thecathedral,which began construction in 1344, but was not completed until the 20th century.[28]

The legendary origins of Prague attribute its foundation to the 8th-century Czech duchess and prophetessLibušeand her husband,Přemysl,founder of thePřemyslid dynasty.Legend says that Libuše came out on a rocky cliff high above the Vltava and prophesied: "I see a great city whose glory will touch the stars". She ordered a castle and a town called Praha to be built on the site.[20]

The region became the seat of thedukes,and laterkings of Bohemia.Under Duke of BohemiaBoleslaus II the Piousthe area became abishopricin 973.[29]Until Prague was elevated toarchbishopricin 1344, it was under the jurisdiction of theArchbishopric of Mainz.[30]

Prague was an important seat for trading where merchants from across Europe settled, including many Jews, as recalled in 965 by theHispano-Jewishmerchant and travelerAbraham ben Jacob.[31]TheOld New Synagogueof 1270 still stands in the city. Prague was also once home to an importantslave market.[32]

At the site of the ford in the Vltava river, KingVladislaus Ihad the first bridge built in 1170, the Judith Bridge (Juditin most), named in honor of his wifeJudith of Thuringia.[33]This bridge was destroyed by a flood in 1342, but some of the original foundation stones of that bridge remain in the river. It was rebuilt and named the Charles Bridge.[33]

In 1257, under KingOttokar II,Malá Strana( "Lesser Quarter" ) was founded in Prague on the site of an older village in what would become theHradčany(Prague Castle) area.[34]This was the district of the German people, who had the right to administer the law autonomously, pursuant toMagdeburg rights.[35]The new district was on the bank opposite of theStaré Město( "Old Town" ), which hadboroughstatus and was bordered by a line of walls and fortifications.

Late Middle Ages

[edit]

Prague flourished during the 14th-century reign (1346–1378) ofCharles IV, Holy Roman Emperorand the king ofBohemiaof the newLuxembourg dynasty.As King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, he transformed Prague into an imperial capital. In the 1470s, Prague had around 70,000 inhabitants and with an area of 360 ha (~1.4 square miles) it was the third-largest city in the Holy Roman Empire.[36]

Charles IV ordered the building of theNew Town(Nové Město) adjacent to theOld Townand laid out the design himself. The Charles Bridge, replacing the Judith Bridge destroyed in the flood just prior to his reign, was erected to connect the east bank districts to the Malá Strana and castle area. In 1347, he foundedCharles University,which remains theoldest universityin Central Europe.[37]

His fatherJohn of Bohemiabegan construction of theGothicSaint Vitus Cathedral,within the largest of the Prague Castle courtyards, on the site of the Romanesque rotunda there. Prague was elevated to an archbishopric in 1344,[38]the year the cathedral was begun.

The city had amintand was a center of trade for German and Italian bankers and merchants. The social order, however, became more turbulent due to the rising power of thecraftsmen'sguilds(themselves often torn by internal conflicts), and the increasing number of poor.[citation needed]

The Hunger Wall, a substantial fortification wall south of Malá Strana and the castle area was built during a famine in the 1360s. The work is reputed to have been ordered by Charles IV as a means of providing employment and food to the workers and their families.[citation needed]

Charles IV died in 1378. During the reign of his son, KingWenceslaus IV(1378–1419), a period of intense turmoil ensued. During Easter 1389, members of the Prague clergy announced that Jews had desecrated the host (Eucharistic wafer) and the clergy encouraged mobs to pillage, ransack and burn the Jewish quarter. Nearly the entire Jewish population of Prague (3,000 people) was murdered.[39][40]

Jan Hus,a theologian andrectorat Charles University, preached in Prague. In 1402, he began giving sermons in theBethlehem Chapel.Inspired byJohn Wycliffe,these sermons focused on what were seen as radical reforms of a corrupt Church. Having become too dangerous for the political and religious establishment, Hus was summoned to theCouncil of Constance,put on trial forheresy,and burned at the stake inKonstanzin 1415.

Four years later Prague experienced itsfirst defenestration,when the people rebelled under the command of the Prague priestJan Želivský.Hus' death, coupled with Czech proto-nationalism andproto-Protestantism,had spurred theHussite Wars.Peasant rebels, led by the generalJan Žižka,along with Hussite troops from Prague, defeated EmperorSigismund,in theBattle of Vítkov Hillin 1420.

During theHussite Warswhen Prague was attacked by "Crusader" and mercenary forces, the city militia fought bravely under the Prague Banner. This swallow-tailed banner is approximately 4 by 6 ft (1.2 by 1.8 m), with a red field sprinkled with small white fleurs-de-lis, and a silver old Town Coat-of-Arms in the center. The words "PÁN BŮH POMOC NAŠE" (The Lord is our Relief/Help) appeared above the coat-of-arms, with a Hussite chalice centered on the top. Near the swallow-tails is a crescent-shaped golden sun with rays protruding.

One of these banners was captured by Swedish troops during theBattle of Prague (1648)when they captured the western bank of theVltava riverand were repulsed from the eastern bank, they placed it in theRoyal Military MuseuminStockholm;although this flag still exists, it is in very poor condition. They also took theCodex Gigasand theCodex Argenteus.The earliest evidence indicates that agonfalonwith a municipal charge painted on it was used for the Old Town as early as 1419. Since this city militia flag was in use before 1477 and during the Hussite Wars, it is the oldest still preserved municipal flag of Bohemia.

In the following two centuries, Prague strengthened its role as a merchant city. Many noteworthy Gothic buildings[41][42]were erected andVladislav Hallof the Prague Castle was added.

Habsburg era

[edit]

In 1526, the Bohemian estates electedFerdinand Iof theHouse of Habsburg.The fervent Catholicism of its members brought them into conflict in Bohemia, and then in Prague, where Protestant ideas were gaining popularity.[44]These problems were not preeminent under Holy Roman EmperorRudolf II,elected King of Bohemia in 1576, who chose Prague as his home. He lived in Prague Castle, where his court welcomed not only astrologers and magicians but also scientists, musicians, and artists. Rudolf was an art lover as well, and Prague became the capital of European culture. This was a prosperous period for the city: famous people living there in that age include the astronomersTycho BraheandJohannes Kepler,the painterArcimboldo,the alchemistsEdward KelleyandJohn Dee,the poetElizabeth Jane Weston,and others.

In 1618, the famoussecond defenestration of Pragueprovoked theThirty Years' War,a particularly harsh period for Prague and Bohemia.Ferdinand IIof Habsburg was deposed, and his place as King of Bohemia taken byFrederick V, Elector Palatine;however his army was crushed in theBattle of White Mountain(1620) not far from the city. Following this in 1621 was an execution of 27 Czech Protestant leaders (involved in the uprising) in Old Town Square and the exiling of many others. Prague was forcibly converted back toRoman Catholicismfollowed by the rest of Czech lands. The city suffered subsequently during the war under an attack byElectorate of Saxony(1631) and during theBattle of Prague (1648).[45]Prague began a steady decline which reduced the population from the 60,000 it had had in the years before the war to 20,000. In the second half of the 17th century, Prague's population began to grow again.Jewshad been in Prague since the end of the 10th century and, by 1708, they accounted for about a quarter of Prague's population.[46]

In 1689, a great fire devastated Prague, but this spurred a renovation and a rebuilding of the city. In 1713–14, a major outbreak ofplaguehit Prague one last time, killing 12,000 to 13,000 people.[47]

In 1744,Frederick the Greatof Prussia invaded Bohemia. He took Prague after a severe and prolonged siege in the course of which a large part of the town was destroyed.[48]Empress Maria Theresaexpelled the Jews from Prague in 1745; though she rescinded the expulsion in 1748, the proportion of Jewish residents in the city never recovered.[49]In 1757 thePrussianbombardment[48]destroyed more than one-quarter of the city and heavily damaged St. Vitus Cathedral. However, a month later, Frederick the Great was defeated and forced to retreat from Bohemia.

The economy of Prague continued to improve during the 18th century. The population increased to 80,000 inhabitants by 1771. Many rich merchants and nobles enhanced the city with a host of palaces, churches and gardens full of art and music, creating aBaroquecity renowned throughout the world to this day.

In 1784, underJoseph II,the four municipalities of Malá Strana, Nové Město, Staré Město, and Hradčany were merged into a single entity. The Jewish district, calledJosefov,was included only in 1850. TheIndustrial Revolutionproduced great changes and developments in Prague, as new factories could take advantage of the coal mines and ironworks of the nearby regions. The first suburb,Karlín,was created in 1817, and twenty years later the population exceeded 100,000.

The revolutions in Europe in 1848also touched Prague, but they were fiercely suppressed. In the following years, theCzech National Revivalbegan its rise, until it gained the majority in the town council in 1861. Prague had a large number of German speakers in 1848, but by 1880 the number of German speakers had decreased to 14% (42,000), and by 1910 to 6.7% (37,000), due to a massive increase in the city's overall population caused by the influx ofCzechsfrom the rest of Bohemia andMoraviaand the increasing prestige and importance of the Czech language as part of the Czech National Revival.

20th century

[edit]

First Czechoslovak Republic

[edit]World War I ended with the defeat of theAustro-Hungarian Empireand the creation of Czechoslovakia. Prague was chosen as its capital and Prague Castle as the seat of presidentTomáš Garrigue Masaryk.At this time Prague was a true European capital with highly developed industry. By 1930, the population had risen to 850,000.

Second World War

[edit]

Hitlerordered theGerman Armyto enter Prague on 15 March 1939, and from Prague Castle proclaimedBohemia and Moravia a German protectorate.For most of its history, Prague had been a multi-ethnic city[50]with important Czech, German and (mostly native German-speaking) Jewish populations.[51]From 1939, when the country was occupied byNazi Germany,Hitler took over Prague Castle. During theSecond World War,most Jews weredeported and killedby the Germans. In 1942, Prague was witness to the assassination of one of the most powerful men inNazi Germany—Reinhard Heydrich—duringOperation Anthropoid,accomplished by Czechoslovak national heroesJozef GabčíkandJan Kubiš.Hitler ordered bloody reprisals.[52]

In February 1945,Prague suffered several bombing raidsby theUS Army Air Forces.701 people were killed, more than 1,000 people were injured and some buildings, factories and historic landmarks (Emmaus Monastery,Faust House,Vinohrady Synagogue) were destroyed.[53]Many historic structures in Prague, however, escaped the destruction of the war and the damage was small compared to the total destruction of many other cities in that time. According to American pilots, it was the result of a navigational mistake. In March, a deliberate raid targeted military factories in Prague, killing about 370 people.[54]

On 5 May 1945, two days before Germany capitulated, anuprisingagainst Germany occurred. Several thousand Czechs were killed in four days of bloody street fighting, with many atrocities committed by both sides. At daybreak on 9 May, the3rd Shock Armyof theRed Armytook the city almost unopposed. The majority (about 50,000 people) of the German population of Prague either fled or wereexpelledby theBeneš decreesin the aftermath of the war.

Cold War

[edit]

Prague was a city in a country under the military, economic, and political control of theSoviet Union(seeIron CurtainandCOMECON). The world's largestStalin Monumentwas unveiled onLetnáhill in 1955 and destroyed in 1962. The 4th Czechoslovak Writers' Congress, held in the city in June 1967, took a strong position against the regime.[55]On 31 October 1967 students demonstrated atStrahov.This spurred the new secretary of theCzechoslovak Communist Party,Alexander Dubček,to proclaim a new deal in his city's and country's life, starting the short-lived season of the "socialism with a human face".It was thePrague Spring,which aimed at the renovation of political institutions in a democratic way. The otherWarsaw Pactmember countries, exceptRomaniaandAlbania,were led by theSoviet Unionto repress these reforms through theinvasion of Czechoslovakiaand the capital, Prague, on 21 August 1968. The invasion, chiefly by infantry and tanks, effectively suppressed any further attempts at reform. The military occupation of Czechoslovakia by theRed Armywould end only in 1991.Jan PalachandJan Zajíccommitted suicide byself-immolationin January and February 1969 to protest against the "normalization"of the country.

After the Velvet Revolution

[edit]

In 1989, after riot police beat back a peaceful student demonstration, theVelvet Revolutioncrowded the streets of Prague, and the capital ofCzechoslovakiabenefited greatly from the new mood. In 1992, theHistoric Centre of Pragueand its monuments were inscribed as a culturalUNESCO World Heritage Site.In 1993, after theVelvet Divorce,Prague became the capital city of the new Czech Republic. From 1995, high-rise buildings began to be built in Prague in large quantities. In the late 1990s, Prague again became an important cultural center of Europe and was notably influenced byglobalisation.[56]In 2000, theIMFandWorld Banksummits took place in Prague andanti-globalization riotstook place here. In 2002, Prague suffered fromwidespread floodsthat damaged buildings and its underground transport system.

Praguelaunched a bidfor the2016 Summer Olympics,[57]but failed to make the candidate cityshortlist.In June 2009, as the result of financial pressures from theglobal recession,Prague's officials chose to cancel the city's planned bid for the2020 Summer Olympics.[58]

On 21 December 2023,a mass shootingtook place atCharles Universityin central Prague. In total, 15 people were killed and 25 injured. It was the deadliest mass murder in the history of the Czech Republic.[59]

Geography

[edit]Prague is situated on theVltavariver. TheBerounkaflows into the Vltava in the suburbs ofLahovice.There are 99 watercourses in Prague with a total length of 340 km (210 mi). The longest streams are Rokytka and Botič.[60]

There are 3 reservoirs, 37 ponds, and 34 retention reservoirs and dry polders in the city. The largest pond is Velký Počernický with 41.76 ha (103.2 acres).[60]The largest body of water is Hostivař Reservoir with 42 hectares (103.8 acres).[61]

In terms of geomorphological division,most of Prague is located in thePrague Plateau.In the south the city's territory extends into the Hořovice Uplands, in the north it extends into theCentral Elbe Tablelowland. The highest point is the top of the hill Teleček on the western border of Prague, at 399 m (1,309 ft) above sea level. Notable hills in the centre of Prague are Petřín with 327 m (1,073 ft) and Vítkov with 270 m (890 ft). The lowest point is the Vltava inSuchdolat the place where it leaves the city, at 172 m (564 ft).[62]

Prague is located approximately at50°5′N14°25′E/ 50.083°N 14.417°E.Prague is approximately at the same latitude asFrankfurt,Germany;[63]Paris,France;[64]andVancouver,Canada.[65]The northernmost point is at50°10′39″N14°31′37″E/ 50.17750°N 14.52694°E,the southernmost point is at49°56′31″N14°23′44″E/ 49.94194°N 14.39556°E,the westernmost point is at50°6′14″N14°13′31″E/ 50.10389°N 14.22528°E,and the easternmost point is at50°5′14″N14°42′23″E/ 50.08722°N 14.70639°E.[66]Farthest geographical points of the city territory are marked physically by so called „Prague Poles".

Climate

[edit]

Prague has anoceanic climate(Köppen:Cfb)[67][68]bordering on ahumid continental climate(Dfb), defined as such by the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm.[69]The winters are relatively cold with average temperatures at about freezing point (0 °C), and with very little sunshine. Snow cover can be common between mid-November and late March although snow accumulations of more than 200 mm (8 in) are infrequent. There are also a few periods of mild temperatures in winter. Summers usually bring plenty of sunshine and the average high temperature of 24 °C (75 °F). Nights can be quite cool even in summer, though. Precipitation in Prague is moderate (600–500 mm or 24–20 in per year) since it is located in therain shadowof theSudetesand other mountain ranges. The driest season is usually winter while late spring and summer can bring quite heavy rain, especially in the form of thundershowers. The number of hours of average sunshine has increased over time.Temperature inversionsare relatively common between mid-October and mid-March bringing foggy, cold days and sometimes moderate air pollution. Prague is also a windy city with common sustained western winds and an average wind speed of 16 km/h (10 mph) that often helps break temperature inversions and clear the air in cold months.

This section containstoo many charts, tables, or data. |

| Climate data forVáclav Havel Airport,Prague Coordinates50°06′01″N14°15′20″E/ 50.10028°N 14.25556°E;elevation: 364 m (1,194 ft);WMO ID:11518; 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1933–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

29.7 (85.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.8 (98.2) |

37.4 (99.3) |

32.8 (91.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

37.4 (99.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

0.3 (32.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

0.4 (32.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.5 (25.7) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

4.6 (40.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.5 (−13.9) |

−28.0 (−18.4) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−28.0 (−18.4) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 20.2 (0.80) |

18.2 (0.72) |

29.2 (1.15) |

27.5 (1.08) |

60.3 (2.37) |

73.1 (2.88) |

79.2 (3.12) |

67.2 (2.65) |

38.5 (1.52) |

34.2 (1.35) |

28.5 (1.12) |

25.9 (1.02) |

502.1 (19.77) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 14.3 (5.6) |

13.1 (5.2) |

7.0 (2.8) |

0.8 (0.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.1) |

4.5 (1.8) |

10.0 (3.9) |

49.9 (19.6) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0mm) | 6.0 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 89.3 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 84.8 | 80.0 | 74.7 | 66.6 | 68.2 | 69.2 | 67.4 | 68.0 | 74.9 | 81.5 | 86.7 | 86.0 | 75.7 |

| Averagedew point°C (°F) | −4.6 (23.7) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

2.0 (35.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.1 (48.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 57.3 | 89.5 | 132.5 | 196.0 | 230.9 | 235.8 | 242.7 | 231.4 | 169.5 | 112.7 | 57.2 | 48.1 | 1,804 |

| Averageultraviolet index | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1:NOAA(dew point 1961-1990)[70][71] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2:Czech Hydrometeorological Institute(humidity and snowfall 1991-2020, extremes)[72][73][74][75]and Weather Atlas[76] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data forClementinum,Prague;WMO ID:11515; extremes 1775–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.4 (63.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

32.8 (91.0) |

37.7 (99.9) |

37.8 (100.0) |

36.8 (98.2) |

33.1 (91.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

20.4 (68.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.5 (−17.5) |

−27.1 (−16.8) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−24.8 (−12.6) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 18.1 (0.71) |

16.2 (0.64) |

26.3 (1.04) |

24.7 (0.97) |

58.1 (2.29) |

68.6 (2.70) |

67.4 (2.65) |

61.9 (2.44) |

33.9 (1.33) |

29.8 (1.17) |

26.2 (1.03) |

22.6 (0.89) |

453.9 (17.87) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 5.8 (2.3) |

4.2 (1.7) |

1.6 (0.6) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (0.3) |

3.6 (1.4) |

16.1 (6.3) |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 76.2 | 71.2 | 65.9 | 58.7 | 58.9 | 59.3 | 58.7 | 60.5 | 67.7 | 73.5 | 77.4 | 76.7 | 67.1 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 52.4 | 81.9 | 129.3 | 187.8 | 216.3 | 218.4 | 229.1 | 224.1 | 168.2 | 110.8 | 52.5 | 46.2 | 1,716.9 |

| Source:Czech Hydrometeorological Institute[77][78][79][80][81][82] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Prague (extremes 1961-2020)[i] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

38.5 (101.3) |

40.2 (104.4) |

39.6 (103.3) |

33.7 (92.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.5 (−13.9) |

−22.5 (−8.5) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

| Source 1:CHMI[83] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2:NCEI[84][85][86] | |||||||||||||

- ^extremes were recorded at Kbely (Prague 19) and Libuš (Prague 4) since 1991, Ruzyně (Prague 6) since 1961 and at Uhříněves (Prague 22) from 1969 to 2012.

Administration

[edit]Administrative division

[edit]

Prague is the capital of the Czech Republic and as such is the regular seat of its central authorities. Since 24 November 1990, it is de facto again a statutory city, but has a specific status of the municipality and the region at the same time. Prague also houses the administrative institutions of theCentral Bohemian Region.

Until 1949, all administrative districts of Prague were formed by the whole one or more cadastral unit, municipality or town. Since 1949, there has been a fundamental change in the administrative division. Since then, the boundaries of many urban districts, administrative districts and city districts are independent of the boundaries of cadastral territories and some cadastral territories are thus divided into administrative and self-governing parts of the city.Cadastral area(for example,VinohradyandSmíchov) are still relevant especially for the registration of land and real estate and house numbering.

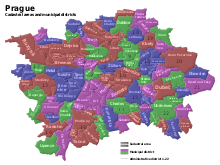

Prague is divided into 10 municipal districts (1–10), 22 administrative districts (1–22), 57 municipal parts, and 112 cadastral areas.

City government

[edit]Prague is administered by the autonomousPrague City Assembly,which consists of 65 members and is elected through municipal elections. The executive body of Prague, elected by the Assembly, isPrague City Council.The municipal office of Prague is atPrague City Halland has 11 members, including themayor.It prepares proposals for the Assembly meetings and ensures that adopted resolutions are fulfilled. TheMayor of PragueisCivic Democratic PartymemberBohuslav Svoboda.

Demographics

[edit]

2011 census

[edit]Even though the official population of Prague hovers around 1.3 million as of the2011 census,the city's real population is much higher due to only 65% of its residents being marked as permanently living in the city.[87]Data taken from mobile phone movements around the city suggest that the real population of Prague is closer to 1.9 or 2.0 million, with an additional 300,000 to 400,000 commuters coming to the city on weekdays for work, education, or commerce.[88]

About 14% of the city's inhabitants were born outside the Czech Republic, the highest proportion in the country. However, 64.8% of the city's population self-identified as ethnicallyCzech,which is slightly higher than the national average of 63.7%. Almost 29% of respondents declined to answer the question on ethnicity at all, so it may be assumed that the real percentage of ethnic Czechs in Prague is considerably higher. The largest ethnic minority areSlovaks,followed by Ukrainians and Russians.[89]

Prague's population is the oldest and best-educated in the country. It has the lowest proportion of children. Only 10.8% of census respondents claimed adherence to a religion; the majority of these wereRoman Catholics.[89]

Historical population

[edit]Development of the Prague population since 1378[90](since 1869 according to the censuses within the limits of present-day Prague):[91][92]

|

|

|

Foreign residents

[edit]As of 31 March 2023, there were 325,336 foreign residents in Prague, of which 118,996 with permanent residence in Prague. The following nationalities are the most numerous:[93]

| Foreign residents in Prague (March 2023) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 147,701 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31,074 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27,130 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15,245 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Culture

[edit]| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Includes | Historic Centre of PragueandPrůhonice Park |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 616 |

| Inscription | 1992 (16thSession) |

| Area | 1,106.36 ha |

| Buffer zone | 9,887.09 ha |

The city is traditionally one of the cultural centres of Europe, hosting many cultural events. Some of the significant cultural institutions include theNational Theatre(Národní Divadlo) and theEstates Theatre(Stavovské or TylovoorNosticovo divadlo), where the premières ofMozart'sDon GiovanniandLa clemenza di Titowere held. Other major cultural institutions are theRudolfinumwhich is home to theCzech Philharmonic Orchestraand theMunicipal Housewhich is home to thePrague Symphony Orchestra.ThePrague State Opera(Státní opera) performs at the Smetana Theatre.

The city has many world-class museums, including theNational Museum(Národní muzeum), the Museum of the Capital City of Prague, theJewish Museum in Prague,theAlfons MuchaMuseum, the African-Prague Museum, theMuseum of Decorative Arts in Prague,theNáprstek Museum(Náprstkovo Muzeum), theJosef Sudek GalleryandThe Josef Sudek Studio,theNational Library,theNational Gallery,which manages the largest collection of art in the Czech Republic and the Kunsthalle Praha, the newest museum in the city.[94]

There are hundreds of concert halls, galleries, cinemas and music clubs in the city. It hostsmusic festivalsincluding thePrague Spring International Music Festival,thePrague Autumn International Music Festival,thePrague International Organ Festival,the Dvořák Prague International Music Festival,[95]and thePrague International Jazz Festival.Film festivals includeBohemia Film Awards,theFebiofest,theOne World Film Festivaland Echoes of theKarlovy Vary International Film Festival.The city also hosts thePrague Writers' Festival,the Prague Folklore Days, Prague Advent Choral Meeting theSummer Shakespeare Festival,[96]thePrague Fringe Festival,theWorld Roma Festival,as well as the hundreds ofVernissagesandfashion shows.

With the growth of low-cost airlines in Europe, Prague has become a weekend city destination allowing tourists to visit its museums and cultural sites as well as try its Czech beers and cuisine.

The city has many buildings by renowned architects, includingAdolf Loos(Villa Müller),Frank O. Gehry(Dancing House) andJean Nouvel(Golden Angel).

Recent major events held in Prague:

- International Monetary FundandWorld BankSummit 2000

- NATOSummit 2002

- International Olympic CommitteeSession 2004

- IAUGeneral Assembly 2006 (Definition of planet)

- EU & USA Summit 2009

- CzechPresidency of the Council of the European Union2009

- USA & Russia Summit 2010 (signing of theNew START treaty)

In popular culture

[edit]The early 1912 silent drama filmPro penízewas filmed mostly in Prague. Many films have been afterwards made atBarrandov Studiosand at Prague Studios. Hollywood films produced in Prague includeMission Impossible,Dungeons and Dragons,xXx,Blade II,Children of Dune,Alien vs. Predator,Doom,Chronicles of Narnia,Hellboy,EuroTrip,Van Helsing,Red Tails,andSpider-Man: Far From Home.[97]Many Indian films have also been filmed in the city includingYuvvraaj,DronaandRockstar.

Among the most famous foreignmusic videosfilmed in Prague are:Never Tear Us ApartbyINXS,Some ThingsbyLasgo,Silver and ColdbyAFI,Diamonds from Sierra LeonebyKanye WestandDon't Stop the MusicbyRihanna.

Video gamesset in Prague includeOsman,Vampire: The Masquerade – Redemption,Soldier of Fortune II: Double Helix,Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness,Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb,Broken Sword: The Sleeping Dragon,Still Life,Metal Gear Solid 4,Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3,Forza Motorsport 5,6andDeus Ex: Mankind Divided.

Cuisine

[edit]

In 2008, theAllegrorestaurant received the firstMichelin starin the whole of the post-Communist part of Central Europe. It retained its star until 2011. As of 2018[update],there were just two Michelin-starred restaurants in Prague:La DegustationBohême Bourgeoise and Field. Another six have been awarded Michelin's Bib Gourmand: Bistrøt 104, Divinis, Eska, Maso a Kobliha, Na Kopci and Sansho. However, as of 2022, there are 27 Michelin-starred restaurants in Prague which still include La Degustation Bohême Bourgeoise and Field.

Czech beerhas a long history, with brewing taking place inBřevnov Monasteryin 993. InOld Town,ŽižkovandVinohradythere are hundreds of restaurants, bars and pubs, especially with Czech beer. Prague also hosts several microbrewery festivals throughout the year. The city is home to historicalbreweriesStaropramen(Praha 5),U Fleků,U Medvídků,U Tří růží,Strahov MonasteryBrewery (Praha 1) andBřevnov MonasteryBrewery (Praha 6). Among many microbreweries are: Novoměstský, Pražský most u Valšů, Národní, Boršov, Loď pivovar, U Dobřenských, U Dvou koček, U Supa (Praha 1), Pivovarský dům (Praha 2), Sousedský pivovar Bašta (Praha 4), Suchdolský Jeník, Libocký pivovar (Praha 6), Marina (Praha 7), U Bulovky (Praha 8), Beznoska, Kolčavka (Praha 9), Vinohradský pivovar, Zubatý pes, Malešický mikropivovar (Praha 10), Jihoměstský pivovar (Praha 11), Lužiny (Praha 13), Počernický pivovar (Praha 14) and Hostivar (Praha 15).

Economy

[edit]

Prague's economy accounts for 25% of the Czech GDP[98]making it the highest performing regional economy of the country. As of 2021, its GDP per capita inpurchasing power standardis €58,216, making it thethird best performing region in the EUat 203 per cent of the EU-27 average in 2021.[99]

Prague employs almost a fifth of the entire Czech workforce, and its wages are significantly above average (≈+20%). In 4Q/2020, during the pandemic, average salaries available in Prague reached CZK 45.944 (≈€1,800) per month, an annual increase of 4%, which was nevertheless lower than national increase of 6.5% both in nominal and real terms. (Inflation in the Czech Republic was 3.2% in 4Q/2020.)[100][101]Since 1990, the city's economic structure has shifted from industrial to service-oriented. Industry is present in sectors such as pharmaceuticals, printing, food processing, manufacture of transport equipment, computer technology, and electrical engineering. In the service sector, financial and commercial services, trade, restaurants, hospitality and public administration are the most significant.Servicesaccount for around 80 per cent of employment. There are 800,000 employees in Prague, including 120,000 commuters.[98]The number of (legally registered) foreign residents in Prague has been increasing in spite of the country's economic downturn. As of March 2010, 148,035 foreign workers were reported to be living in the city making up about 18 per cent of the workforce, up from 131,132 in 2008.[102]Approximately one-fifth of all investment in the Czech Republic takes place in the city.

Almost one-half of the national income from tourism is spent in Prague. The city offers approximately 73,000 beds in accommodation facilities, most of which were built after 1990, including almost 51,000 beds in hotels and boarding houses.

From the late 1990s to late 2000s, the city was a common filming location for international productions such as Hollywood and Bollywood motion pictures. A combination of architecture, low costs and the existing motion picture infrastructure have proven attractive to international film production companies.

The modern economy of Prague is largely service and export-based and, in a 2010 survey, the city was named the best city in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) for business.[103]

In 2005, Prague was deemed among the three best cities in Central and Eastern Europe according toThe Economist's livability rankings.[104]The city was named as a top-tier nexus city for innovation across multiple sectors of the global innovation economy, placing 29th globally out of 289 cities, ahead ofBrusselsandHelsinkifor innovation in 2010.[105]

Na příkopěis the most expensive street among all the states of theV4.[106]In 2017, with the amount of rent €2,640 (CZK 67,480) per square meter per year, ranked on 22nd place among the most expensive streets in the world.[107]The second most expensive is Pařížská street.

In the Eurostat research, Prague ranked fifth among Europe's 271 regions in terms of gross domestic product per inhabitant, achieving 172 per cent of the EU average. It ranked just above Paris and well above the country as a whole, which achieved 80 per cent of the EU average.[108][109]

Companies with highest turnover in the region in 2014:[110]

| Name | Turnover, mld. CZK |

|---|---|

| ČEZ | 200.8 |

| Agrofert | 166.8 |

| RWE Supply & Trading CZ | 146.1 |

Prague is also the site of some of the most important offices and institutions of the Czech Republic

- President of the Czech Republic

- TheGovernmentand both houses ofParliament

- Ministries and other national offices (Industrial Property Office,Czech Statistical Office,National Security Authority, etc.)

- Czech National Bank

- Czech Televisionand other major broadcasters

- Radio Free Europe–Radio Liberty

- Galileoglobal navigation project

- Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic

Tourism

[edit]

Sincethe fall of the Iron Curtain,Prague has become one of the world's most popular tourist destinations. Praguesuffered considerably lessdamage duringWorld War IIthan some other major cities in the region, allowing most of its historic architecture to stay true to form. It contains one of the world's most pristine and varied collections of architecture, fromRomanesque,toGothic,Renaissance,Baroque,Rococo,Neo-Renaissance,Neo-Gothic,Art Nouveau,Cubist,Neo-Classicaland ultra-modern.

Prague is classified as an "Alpha-"global cityaccording toGaWCstudies, comparable toVienna,ManilaandWashington, D.C.[111]Prague ranked sixth in theTripadvisorworld list of best destinations in 2016.[112]Its rich history makes it a popular tourist destination, and the city receives more than 8.4 million international visitors annually, as of 2017[update].Furthermore, the city was ranked 7th in the worldICCADestination Performance Index measuring performance of conference tourism in 2021.[113]

Main attractions

[edit]Hradčany and Lesser Town (Malá Strana)

[edit]- Prague Castlewith theSt. Vitus Cathedralwhich stores theCzech Crown Jewels

- TheCharles Bridge(Karlův most)

- The BaroqueSaint Nicholas Church

- Church of Our Lady VictoriousandInfant Jesus of Prague

- Písek Gate,one of the last preserved city gate of Baroque fortification

- Petřín Hill withPetřín Lookout Tower,Mirror Maze andPetřín funicular

- Lennon Wall

- TheFranz Kafka Museum

- Kampa Island,an island with a view of the Charles Bridge[114]

- The BaroqueWallenstein Palacewith its garden

Old Town (Staré Město) and Josefov

[edit]- TheAstronomical Clock(Orloj) onOld TownCity Hall

- The GothicChurch of Our Lady before Týn(Kostel Matky Boží před Týnem) from the 14th century with 80 m high towers

- Stone Bell House

- The vaulted GothicOld New Synagogue(Staronová Synagoga) of 1270

- Old Jewish Cemetery

- Powder Tower(Prašná brána), a Gothic tower of the old city gates

- Spanish Synagoguewith its elaborate interior decoration

- Old Town Square(Staroměstské náměstí) with gothic and baroque architectural styles

- The art nouveauMunicipal House,a major civic landmark and concert hall known for itsArt Nouveauarchitectural style and political history in the Czech Republic.

- Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague,with an extensive collections including glass, furniture, textile, toys, Art Nouveau, Cubism and Art Deco

- Clam-Gallas Palace,a baroque palace from 1713

- Church of St. Martin in the Wall

- Colloredo-Mansfeld Palace, with elements of HighBaroqueand the laterRococoand Second-Rococo adaptations. Known today for its well-preserved dance hall[115][116]

- St. Clement's Cathedral, Prague

New Town (Nové Město)

[edit]- Busy and historicWenceslas Square

- The neo-renaissanceNational Museumwith large scientific and historical collections at the head of Wenceslas Square. It is the largest museum in the Czech Republic, covering disciplines from the natural sciences to specialized areas of the social sciences. The staircase of the building offers a nice view of the New Town.

- TheNational Theatre,a neo-Renaissance building with golden roof, alongside the banks of the Vltava river

- ThedeconstructivistDancing House(Fred and Ginger Building)

- Charles Square,the largest medieval square in Europe (now turned into a park)

- TheEmmaus monasteryandWW I Memorial"Prague to Its Victorious Sons" at Palacky Square (Palackého náměstí)

- The museum of theHeydrich assassinationin the crypt of theChurch of Saints Cyril and Methodius

- Stiassny'sJubilee Synagogueis the largest in Prague

- The Mucha Museum, showcasing theArt Nouveauworks ofAlphonse Mucha

- Church of St. Apollinaire, Prague

- Church of Saint Michael the Archangel in Prague

- Church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary and St. Charles the Great, Prague

- Church of Our Lady on the Lawn

- St. Wenceslas Church (Zderaz)

- St. Stephen's Church

Vinohrady and Žižkov

[edit]- National Monument in Vitkovwith a large bronze equestrian statue ofJan Žižkain Vítkov Park, Žižkov –Prague 3

- The neo-GothicChurch of St. Ludmilaat Míru Square inVinohrady

- Žižkov Television Tower

- New Jewish Cemeteryin Olšany, location ofFranz Kafka's grave –Prague 3

- The Roman CatholicSacred Heart Churchat Jiřího z Poděbrad Square

- TheVinohradygrand Neo-Renaissance, Art Nouveau, Pseudo Baroque, and Neo-Gothic buildings in the area between Míru Square,Jiřího z Poděbrad Squareand Havlíčkovy sady park[117]

Other places

[edit]- Vyšehrad CastlewithBasilica of St Peter and St Paul,Vyšehrad cemeteryand Prague oldest Rotunda of St. Martin

- ThePrague MetronomeatLetná Park,a giant, functional metronome that looms over the city

- Prague ZooinTroja,selected as the 7th best zoo in the world byForbesmagazine in 2007[118]and the 4th best byTripAdvisorin 2015[119]

- Industrial Palace(Průmyslový palác),Křižík's Light fountain,funfairLunaparkand Sea World Aquarium inVýstaviště compoundinHolešovice

- Letohrádek Hvězda(Star Villa) inLiboc,a renaissance villa in the shape of a six-pointed star surrounded by a game reserve

- National Gallery in Praguewith large collection of Czech and international paintings and sculptures by artists such asMucha,Kupka,Picasso,MonetandVan Gogh

- Opera performances inNational Theatre– unlike drama, all opera performances run with English subtitles.

- Anděl,a busy part of the city with modern architecture and ashopping mall

- The largeNusle Bridge,spans theNusleValley, linking New Town toPankrác,with the Metro running underneath the road

- Strahov Monastery,an old Czechpremonstratensianabbey founded in 1149 and monastic library

- Hotel International Prague,a four-star hotel and Czech cultural monument

-

TheCharles Bridgeis a historic bridge from the 14th century.

-

Prague Castleis the biggest ancient castle in the world.

-

National Theatreoffers opera, drama, ballet and other performances.

-

Náměstí Míru Square withVinohradyTheatre andChurch of St. Ludmila

-

Vyšehradfortress containsBasilica of St Peter and St Paul,theVyšehrad Cemeteryand the oldest Rotunda of St. Martin.

-

View of Pařížská St. fromLetná Park

-

Old New Synagogueis Europe's oldest active synagogue. Legend hasGolemlying in the loft.

-

National Monument on VítkovHill, the statue ofJan Žižkais the third largest bronzeequestrian statuein the world.

-

Prague Zoo,selected in 2015 as the fourth best zoo in the world byTripAdvisor

Tourism statistics

[edit]Prague is by far the most visited Czech city. In 2023, Prague was visited by 7,442,614 guests who stayed overnight, of which 78.8% were from abroad. Average number of overnight stays of non-residents was 2.3. Most non-residents arriving to Prague and staying overnight were from the following countries:[120]

| Rank | Country | 2023 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 7,442,614 | 6,803,741 | |

| 1 | 1,029,856 | 900,526 | |

| 2 | 424,346 | 511,950 | |

| 3 | 399,185 | 495,728 | |

| 4 | 369,868 | 310,966 | |

| 5 | 331,834 | 252,633 | |

| 6 | 324,696 | 335,101 | |

| 7 | 200,370 | 248,911 | |

| 8 | 198,134 | 170,305 | |

| 9 | 194,571 | 227,345 | |

| 10 | 162,753 | 148,520 | |

| 11 | 155,583 | 272,451 | |

| 12 | 151,259 | 132,500 | |

| 13 | 104,924 | 108,175 | |

| 23,517 | 392,968 | ||

| 63,253 | 309,299 |

In 2023, the most visited tourist destinations of Prague were:[121]

| Rank | Destination | Number of visitors (in thousands) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prague Castle | 2,191.8 |

| 2 | Petřín funicular | 1,915.7 |

| 3 | Prague Zoo | 1,358.4 |

| 4 | Petřín Lookout Tower | 643.1 |

| 5 | Old Town Hall | 560.8 |

| 6 | Prague Botanical Garden | 412.9 |

| 7 | Mirror Maze on Petřín Hill | 378.5 |

| 8 | Království železnic Smíchov | 320.2 |

| 9 | Chairlift in Prague Zoo | 305.6 |

| 10 | Municipal House | 261.0 |

Education

[edit]Nine public universities and thirty six private universities are located in the city, including:[122]

Public universities

[edit]

- Charles University(UK) founded in 1348, theoldestuniversity in Central Europe

- Czech Technical University(ČVUT) founded in 1707

- University of Chemistry and Technology(VŠCHT) founded in 1920

- University of Economics(VŠE) founded in 1953

- Czech University of Life Sciences Prague(ČZU) founded in 1906/1952

- Czech Police Academy (PA ČR) founded in 1993

Public arts academies

[edit]- Academy of Fine Arts(AVU) founded in 1800

- Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design(VŠUP) founded in 1885

- Academy of Performing Arts(AMU) founded in 1945

Private universities

[edit]- Jan Amos Komenský University (UJAK) founded in 2001

- Metropolitan University Prague(MUP) founded in 2001

- The University of Finance and Administration(VSFS) founded in 1999

Largest private colleges

[edit]- University College of Business in Prague(VŠO) founded in 2000

- University of Economics and Management(VŠEM) founded in 2001

- College of Entrepreneurship and Law(VŠPP) founded in 2000

- Institute of Hospitality Management(VŠH) founded in 1999

- College of International and Public Relations Prague(VŠMVV) founded in 2001

- CEVRO Institute(CEVRO) founded in 2005

- Ambis College(AMBIS) founded in 1994

- Medical College of Nursing(Vysoká škola zdravotnická) founded in 2005

- Anglo-American University(AAVŠ) founded in 2000

- University of New York in Prague(UNYP) founded in 1998

International institutions

[edit]Science, research and hi-tech centres

[edit]

The region city of Prague is an important centre of research. It is the seat of 39 out of 54 institutes of theCzech Academy of Sciences,including the largest ones, the Institute of Physics, the Institute of Microbiology and the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry. It is also a seat of 10 public research institutes, fourbusiness incubatorsand large hospitals performingresearch and developmentactivities such as theMotol University HospitalorInstitute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine,which was the largest transplant center inEuropeas of 2019.[123]Universities seated in Prague (see sectionColleges and Universities) also represent important centres of science and research activities.

As of 2008[update],there were 13,000 researchers (out of 30,000 in the country, counted in full-time equivalents), representing a 3% share of Prague's economically active population. Gross expenditure on research and development accounted for €901.3 million (41.5% of country's total).[124]

Some well-known multinational companies have established research and development facilities in Prague, among themSiemens,Honeywell,Oracle,MicrosoftandBroadcom.

Prague was selected to host administration of the EU satellite navigation systemGalileo.It started to provide its first services in December 2016 and full completion is expected by 2020.

Transport

[edit]As of 2017[update],Prague's transportmodal shareby journey was 52% public transport, 24.5% by car, 22.4% on foot, 0.4% by bicycle and 0.5% by aeroplane.[125]

Public transportation

[edit]

The public transport infrastructure consists of the heavily usedPrague Integrated Transport(PID,Pražská integrovaná doprava) system, consisting of thePrague Metro(linesA,B,andC– its length is 65 km (40 mi) with 61 stations in total),Prague tram system,Prague buses service,commuter trains,funiculars,and sevenferries.Prague has one of the highest rates of public transport usage in the world,[126]with 1.2 billion passenger journeys per year.

Prague has about 300 bus lines (numbers 100–960) and 34 regular tram lines (numbers 1–26 and 91–99). As of 2022 the bus lines are being extended withtrolley buslines.

There are also threefuniculars,thePetřín funicularonPetřín Hill,one on Mrázovka Hill and a third at theZoo in Troja.

The Prague tram systemnow operates various types of trams, including theTatra T3,newerTatra KT8D5,Škoda 14 T(designed byPorsche), newer modernŠkoda 15 Tand nostalgic tram lines 23 and 41. Around 400 vehicles are the modernizedT3class, which are typically operated coupled together in pairs.

The Prague tram system is thetwelfth longestin the world (144 km) and its rolling stock consists of 786 individual cars,[127]which is the largest in the world. The system carries more than 360 million passengers annually, the highest tram patronage in the world afterBudapest,on a per capita basis, Prague has the second highest tram patronage afterZürich.

All services (metro, tramways, city buses, funiculars and ferries) have a common ticketing system that operates on aproof-of-paymentsystem. Basic transfer tickets can be bought for 30 and 90-minute rides, short-term tourist passes are available for periods of 24 hours or 3 days, and longer-term tickets can be bought on the smart ticketing systemLítačka,for periods of one month, three months or one year.[128]Since August 2021, people up to the age of 14 and over 65 can use Prague's public transport free of charge (proof of age is required). Persons between 15 and 18 years and between 60 and 64 years pay half price for single tickets and day tickets.

Services are run by the Prague Public Transport Company and several other companies. Since 2005 theRegional Organiser of Prague Integrated Transport (ROPID)has franchised operation of ferries on theVltavariver, which are also a part of the public transport system with common fares.Taxiservices make pick-ups on the streets or operate from regulated taxi stands.

Prague Metro

[edit]

TheMetrohas three major lines extending throughout the city:A(green),B(yellow) andC(red). A fourth Metroline Dis under construction, which will connect the city centre to southern parts of the city (as of 2022, the completion is expected in 2028).[129][130]The Prague Metro system served 589.2 million passengers in 2012,[131]making it thefifth busiest metro system in Europeand the most-patronised in the world on a per capita basis. The first section of the Prague metro was put into operation in 1974. It was the stretch between stationsKačerovandFlorencon the currentline C.The first part ofLine Awas opened in 1978 (Dejvická–Náměstí Míru), the first part ofline Bin 1985 (Anděl–Florenc).

In April 2015, construction finished to extend the green line A further into the northwest corner of Prague closer to the airport.[132]A new interchange station for the bus in the direction of the airport is the stationNádraží Veleslavín.The final station of the green line isNemocnice Motol(Motol Hospital), giving people direct public transportation access to the largest medical facility in the Czech Republic and one of the largest in Europe. A railway connection to the airport is planned.

In operation there are two kinds of units: "81-71M" which is modernized variant of the SovietMetrovagonmash 81-71(completely modernized between 1995 and 2003) and new "Metro M1"trains (since 2000), manufactured by consortium consisting ofSiemens,ČKD PrahaandADtranz.The minimum interval between two trains is 90 seconds.

The original Soviet vehicles "Ečs"were excluded in 1997, but one vehicle is placed in public transport museum in depotStřešovice.[133]TheNáměstí Mírumetro station is the deepest station and is equipped with the longestescalatorinEuropean Union.ThePrague metrois generally considered very safe.

Roads

[edit]

The main flow of traffic leads through the centre of the city and through inner and outer ring roads (partially in operation).

- Inner Ring Road(The City Ring "MO" ): surrounds central Prague. It is the longest citytunnelinEuropewith a length of 5.5 km (3.4 mi) and five interchanges has been completed to relieve congestion in the north-western part of Prague. CalledBlanka tunnel complexand part of the City Ring Road, it was estimated to eventually cost (after several increases)CZK43 billion. Construction started in 2007 and, after repeated delays, the tunnel officially opened in September 2015. This tunnel complex completes a major part of the inner ring road.

- Outer Ring Road(The Prague Ring "D0" ):this ring road will connect all major motorways and speedways that meet each other in Prague region and provide faster transit without a necessity to drive through the city. So far 39 km (24 mi), out of a total planned 83 km (52 mi), is in operation. Most recently, the southern part of this road (with a length of more than 20 km (12 mi)) was opened on 22 September 2010.[134]As of 2021, the next 12 km (7 mi) section betweenModleticeandBěchoviceis planned to be completed in 2025.[135]

Rail

[edit]

The city forms the hub of theCzech railwaysystem, with services to all parts of the country and abroad. The railway system links Prague with major European cities (which can be reached without transfers), includingDresden,Berlin,Hamburg,Leipzig,RegensburgandMunich(Germany);Vienna,GrazandLinz(Austria);Warsaw,KrakówandPrzemyśl(Poland);Bratislava,PopradandKošice(Slovakia);Budapest(Hungary);BaselandZürich(Switzerland). Travel times range between 2 hours to Dresden and 13 hours to Zürich.[136]

Prague's main international railway station isHlavní nádraží,[137]rail services are also available from other main stations:Masarykovo nádraží,HolešoviceandSmíchov,in addition to suburban stations. Commuter rail services operate under the nameEsko Praha,which is part ofPID(Prague Integrated Transport).

Air

[edit]Prague is served byVáclav Havel Airport Prague,the largest airport in the Czech Republic and one of the largest and busiest airports in central and easternEurope.The airport is the hub of carriersSmartwingsandCzech Airlinesoperating throughout Europe. Other airports in Prague include the city'soriginal airportin the north-eastern district ofKbely,which is serviced by theCzech Air Force,also internationally. It also houses thePrague Aviation Museum.The nearby Letňany Airport is mainly used for private aviation and aeroclub aviation. Anotherairportin the proximity isAero Vodochodyaircraft factory to the north, used for testing purposes, as well as for aeroclub aviation. There are a few aeroclubs around Prague, such as theTočná airfield.

Cycling

[edit]In 2018, 1–2.5 % of people commute bybike in Prague,depending on season. Cycling is very common as a sport or recreation.[138]As of 2019, there were 194 km (121 mi) of protected cycle paths and routes. Also, there were 50 km (31 mi) ofbike lanesand 26 km (16 mi) of specially marked bus lanes that are free to be used by cyclists.[139]As of 2024, there are four companiesproviding bicycle sharingin Prague:Rekola(1,000 bikes),Nextbike(1,000 bikes),BoltandLime.Bikesharing is partly connected to the public transportation and subsidised by the city.

Sport

[edit]Prague is the site of many sports events, national stadiums and teams.

Teams

[edit]- Sparta Prague(Czech First League) – football club

- Slavia Prague(Czech First League) – football club

- Bohemians 1905(Czech First League) – football club

- Dukla Prague(Czech 2nd Football League) – football club

- Viktoria Žižkov(Czech 2nd Football League) – football club

- HC Sparta Praha(Czech Extraliga) – ice hockey club

- HC Slavia Praha(Czech 2nd Hockey League) – ice hockey club

- USK Praha(National Basketball League) – basketball club

- Prague Lions(European League of Football) –American football

- AK Markéta Praha(speedway club)

- PSK Olymp Praha(athletics club)

Stadia and arenas

[edit]

- O2 Arena– the second largest ice hockey arena in Europe. It hosted2004and2015 Ice Hockey World Championship,NHL2008 and 2010 Opening Game andEuroleagueFinal Four.

- Strahov Stadium– the largest stadium in the world.[140]

- Fortuna Arena,football stadium

- I. ČLTK Prague,tennis club

- Markéta Stadium,speedway and athletics stadium

- Stadion Juliska,football and athletics stadium

- Gutovka– sport area with a large concreteskatepark,the highest outdoorclimbing wallin Central Europe, fourbeach volleyballcourts and children's playground;[141]Central European Beach Volleyball Championship 2018 took place here.

Events

[edit]- Prague International Marathon

- Prague Open– Tennis Tournament

- Prague Chess Festival

- Sparta Prague Open– Tennis Tournament held atTK Sparta PragueinPrague 7

- Josef Odložil Memorial– athletics meeting

- WorldUltimateClub Championships 2010 concluded in Strahov and Eden Arena.[142]

- Mystic SK8 Cup –World Cup of Skateboardingvenue held at theŠtvaniceskatepark

International relations

[edit]

The city of Prague maintains its own EU delegation inBrusselscalled Prague House.[143]

Prague was the location ofU.S. PresidentBarack Obama's speech on 5 April 2009, which led to theNew STARTtreaty with Russia, signed in Prague on 8 April 2010.[144]

The annual conferenceForum 2000,which was founded by former Czech PresidentVáclav Havel,Japanese philanthropistYōhei Sasakawa,and Nobel Peace Prize laureateElie Wieselin 1996, is held in Prague. Its main objective is "to identify the key issues facing civilization and to explore ways to prevent the escalation of conflicts that have religion, culture or ethnicity as their primary components", and also intends to promote democracy in non-democratic countries and to support civil society. Conferences have attracted a number of prominent thinkers, Nobel laureates, former and acting politicians, business leaders and other individuals like:Frederik Willem de Klerk,Bill Clinton,Nicholas Winton,Oscar Arias Sánchez,Dalai Lama,Hans Küng,Shimon PeresandMadeleine Albright.

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Prague istwinnedwith:

Namesakes

[edit]A number of other settlements are derived or similar to the name of Prague. In many of these cases, Czech emigration has left a number of namesake cities scattered over the globe, with a notable concentration in theNew World.

|

Additionally,Kłodzkois sometimes referred to as "Little Prague" (‹See Tfd›German:Klein-Prag). Although now inPoland,it had been traditionally a part ofBohemiauntil 1763 when it became part ofSilesia.[159]

See also

[edit]- Churches in Prague

- List of people from Prague

- Outline of the Czech Republic

- Outline of Prague

- List of museums in Prague

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcVáclav Vojtíšek,Znak Hlavního Města Prahy / Les Armoires de la Ville de PragueArchived17 April 2016 at theWayback Machine(1928), cited afternakedtourguidepragueArchived9 October 2016 at theWayback Machine(2015).

- ^Milan Ducháček,Václav Chaloupecký: Hledání československých dějinArchived18 April 2023 at theWayback Machine(2014), cited afterabicko.avcr.czArchived16 April 2018 at theWayback Machine.

- ^"Demographia World Urban Areas"(PDF).Demographia.Archived(PDF)from the original on 3 May 2018.Retrieved18 November2013.

- ^"OECD - Metropolitan areas - Population, all ages".OECD.Archivedfrom the original on 12 April 2019.Retrieved15 January2022.

- ^"Population of Municipalities – 1 January 2024".Czech Statistical Office.17 May 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2024.Retrieved17 May2024.

- ^"EU regions by GDP, Eurostat".ec.europa.eu.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2023.Retrieved18 September2023.

- ^"Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions".ec.europa.eu.Archivedfrom the original on 15 February 2023.

- ^"Sub-national HDI – Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab".Archivedfrom the original on 23 September 2018.Retrieved10 August2018.

- ^ab"Brief History of Prague, Czech Republic | Prague".prague.Archivedfrom the original on 22 February 2024.Retrieved27 March2024.

- ^"Short History of Bohemia, Moravia and then Czechoslovakia and Czech Republic".hedgie.eu.2015. Archived fromthe originalon 18 May 2016.Retrieved7 April2016.

- ^"The World According to GaWC 2020".GaWC.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2023.Retrieved8 October2023.

- ^"Quality of Living City Ranking".Mercer: Global Mobility Solutions.Archivedfrom the original on 18 April 2018.Retrieved30 May2019.

- ^"The PICSA Index".PICSA.Archived fromthe originalon 8 March 2021.Retrieved2 July2021.

- ^"Top 100 City Destinations Revealed: Prague among Most Visited in the World".Expats.cz.8 November 2017. Archived fromthe originalon 29 August 2018.Retrieved28 August2018.

- ^"What's in a Name? (Prague History Lesson)".Prague Summer Program for Writers.22 February 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2017.Retrieved14 March2016.

- ^Dudák, Vladislav (2010).Praha: Průvodce magickým centrem Evropy[Prague: A Guide to the Magical Center of Europe]. Praha: Práh. p. 184.ISBN978-80-7252-302-3.

- ^"Interview with Lady Diana Cooper".Desert Island Discs.24 March 1969.Archivedfrom the original on 3 February 2019.Retrieved2 February2019.

- ^"Kolik věží má" stověžatá "Praha? Nadšenci jich napočítali přes pět set".idnes.cz(in Czech). Mladá fronta DNES. 5 August 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 14 May 2013.Retrieved8 January2013.

- ^"Visit Prague, the City of a Hundred spires".prague.fm.Archivedfrom the original on 10 August 2015.Retrieved19 August2015.

- ^abcdDemetz, Peter (1997)."Chapter One: Libussa, or Versions of Origin".Prague in Black and Gold: Scenes from the Life of a European City.New York: Hill and Wang.ISBN978-0-8090-7843-1.Retrieved7 April2016.

- ^abDovid Solomon Ganz, Tzemach Dovid (3rd edition), part 2, Warsaw 1878, pp. 71, 85 (onlineArchived21 April 2022 at theWayback Machine)

- ^Kenety, Brian (29 October 2004)."Unearthing Bohemia's Celtic heritage ahead of Samhain, the 'New Year'".Czech Radio.Archivedfrom the original on 10 August 2016.Retrieved9 August2016.

- ^Kenety, Brian (19 November 2005)."Atlantis české archeologie"(in Czech). Czech Radio.Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2016.Retrieved9 August2016.

- ^"Praha byla Casurgis"[Prague was Casurgis] (in Czech). cs-magazin. February 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 13 April 2016.Retrieved7 April2016.

- ^"Slované na Hradě žili už sto let před Bořivojem –".Novinky.cz.Archivedfrom the original on 5 April 2011.Retrieved14 April2011.

- ^"Archaeological Research – Prague Castle".Hrad.cz. 8 July 2005. Archived fromthe originalon 1 April 2009.Retrieved30 May2011.

- ^"TOP MONUMENTS – VYŠEHRAD".praguewelcome.cz. Archived fromthe originalon 12 March 2013.Retrieved14 November2013.

- ^"5 of the Best Gothic Buildings in Prague".Architectural Digest.Archivedfrom the original on 23 August 2018.Retrieved23 August2018.

- ^Wolverton, Lisa (9 October 2012).Hastening Toward Prague: Power and Society in the Medieval Czech Lands.University of Pennsylvania Press.ISBN978-0812204223.Archivedfrom the original on 10 April 2022.Retrieved28 October2020.

- ^"Prague – an architectural gem in the heart of Europe | Radio Prague".Radio Praha.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2018.Retrieved23 August2018.

- ^Rothkirchen, Livia(1 January 2006).The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia: Facing the Holocaust.U of Nebraska Press.ISBN978-0803205024.Archivedfrom the original on 10 April 2022.Retrieved28 October2020.

- ^"The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: Trade and industry in the Middle AgesArchived3 May 2016 at theWayback Machine".Michael Moïssey Postan, Edward Miller, Cynthia Postan (1987).Cambridge University Press.p. 417.ISBN0-521-08709-0.

- ^ab"History of Charles Bridge | Radio Prague".Radio Praha.Archivedfrom the original on 5 September 2019.Retrieved23 August2018.

- ^Guides, Rough (16 January 2015).The Rough Guide to Prague.Rough Guides UK.ISBN9780241196311.Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2022.Retrieved28 October2020.

- ^Dickinson, Robert E.(2003).The West European City: A Geographical Interpretation.Taylor & Francis.ISBN9780415177115.Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2022.Retrieved28 October2020.

- ^"Deset století architektury (1997) [TV cyklus] - Nové Město pražské (1998), 2. série - 21. díl".FDb.cz(in Czech).Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2023.Retrieved4 March2023.

- ^"Charles University Official Website".Archivedfrom the original on 29 October 2007.Retrieved21 April2022.

- ^Palmitessa, James (2002)."The Archbishops of Prague in Urban Struggles of the Confessional Age 1561–1612"(PDF).Bohemian Reformation and Religious Practice.4:261–273.Archived(PDF)from the original on 25 February 2019.Retrieved24 February2019.

- ^"The Prague Pogrom of 1389".Everything2. April 1389.Archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2010.Retrieved16 June2009.

- ^"The former Jewish Quarter in Prague".prague.cz. April 1389.Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2009.Retrieved16 June2009.

- ^"Architecture of the Gothic".Old.hrad.cz. 13 October 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 8 August 2013.Retrieved18 November2013.

- ^"Old Royal Palace with Vladislav Hall – Prague Castle".Hrad.cz. 16 December 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 1 April 2009.Retrieved18 November2013.

- ^ This swallow-tailed banner is approximately 4 by 6 ft (1.2 by 1.8 m), with a red field sprinkled with small white fleurs-de-lis, and a silver old Town Coat-of-Arms in the centre. The wordsPÁN BŮH POMOC NAŠE(The Lord God is our Help) appeared above the coat-of-arms, with a Hussite "host with chalice" centered on the top. Near the swallow-tails is a crescent-shaped golden sun with rays protruding. One of these banners was captured by Swedish troops inBattle of Prague (1648),when they captured the western bank of the Vltava River and were repulsed from the eastern bank, they placed it in the Royal Military Museum inStockholm;although this flag still exists, it is in very poor condition. They also took theCodex Gigasand theCodex Argenteus.The earliest evidence indicates that a gonfalon with a municipal charge painted on it was used for Old Town as early as 1419. Since this city militia flag was in use before 1477 and during the Hussite Wars, it is the oldest still preserved municipal flag of Bohemia.[citation needed]

- ^"Religious conflicts".Prague.st.Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2016.Retrieved18 November2013.

- ^"The Kingdom of Bohemia during the Thirty Years' War".Family-lines.cz.Archivedfrom the original on 18 July 2011.Retrieved14 April2011.

- ^"Prague".Jewish Virtual Library.Archivedfrom the original on 13 January 2017.Retrieved18 November2013.

- ^M. Signoli, D. Chevé, A. Pascal (2007)."Plague epidemics in Czech countriesArchived3 May 2016 at theWayback Machine".p.51.

- ^abChisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 248–250.

- ^"The Jewish History of Prague".Aish.6 October 2022.Retrieved8 July2024.

- ^"Einwohnerzahl europäischer Städte"(PDF)(in German).Archived(PDF)from the original on 17 May 2018.Retrieved6 July2018.

Prag insgesamt 1940 928.000

- ^"Aus der Geschichte jüdischer Gemeinden"(in German).Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2022.Retrieved21 April2022.

1937/38 ca. 45.000

- ^Bryant, Chad (2007).Prague in Black: Nazi Rule and Czech Nationalism.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 167ff.ISBN978-0674024519

- ^"Looking Back at the Bombing of Prague".The Prague Post.14 February 1945.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2012.Retrieved4 December2011.

- ^"The bombing of Prague from a new perspective".Radio Prague. 13 December 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 20 February 2018.Retrieved10 June2018.

- ^Pehe, Jiří(6 November 2008)."Post-Communist Reflections of the Prague Spring".Jiří Pehe.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2017.Retrieved7 September2017.

- ^McAdams, Michael (1 September 2007)."Global Cities as Centers of Cultural Influence: A Focus on Istanbul, Turkey".Transtext(e)s Transcultures.No. 3. pp. 151–165.doi:10.4000/transtexts.149.ISSN1771-2084.Archivedfrom the original on 15 July 2018.Retrieved15 July2018.

- ^"Prague Assembly Confirms 2016 Olympic Bid".Gamesbids. Archived fromthe originalon 7 August 2011.Retrieved14 April2011.

- ^"It's Official – Prague Out of 2020 Bid".GamesBids.16 June 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 10 September 2010.Retrieved14 April2011.

- ^Lopatka, Jan; Hovet, Jason (22 December 2023)."Gunman kills 14 in unprecedented attack at Prague university".Reuters.Retrieved29 December2023.

- ^ab"Vodní toky a vodní díla v Praze"(in Czech). City of Prague.Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2022.Retrieved26 March2022.

- ^"Hostivařská přehrada není jen na koupání, ale i na výlet"[Hostivař dam is not only for swimming but also for a trip] (in Czech). Hostivař Reservoir.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2021.Retrieved26 March2022.

- ^"Sedm pražských NEJ aneb Neznámý kopec Teleček"(in Czech). E15. 6 April 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 14 May 2021.Retrieved26 March2022.

- ^"Latitude and Longitude of World Cities: Frankfurt".Archivedfrom the original on 24 May 2011.Retrieved27 May2011.

- ^"Latitude and Longitude of World Cities".Archivedfrom the original on 24 May 2011.Retrieved27 May2011.

- ^"Latitude and Longitude of Vancouver, Canada".Archivedfrom the original on 25 January 2012.Retrieved27 May2011.