Diponegoro

| Diponegoro | |

|---|---|

| Sultan Abdul Hamid Herucakra Amirul Mukminin Sayyidin Panatagama Kalifatullah ing Tanah Jawa | |

Portrait of Prince Diponegoro, 1835 | |

| Born | 11 November 1785 Yogyakarta Sultanate |

| Died | 8 January 1855(aged 69) Oedjoeng Pandang,Dutch East Indies |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue | 17 sons, 5 daughters |

| House | Mataram |

| Father | Hamengkubuwana III |

| Mother | Mangkarawati |

| Religion | Islam |

PrinceDiponegoro(Javanese:ꦢꦶꦥꦤꦼꦒꦫ,Dipånegårå;bornBendara Raden Mas Mustahar,ꦧꦼꦤ꧀ꦢꦫꦫꦢꦺꦤ꧀ꦩꦱ꧀ꦩꦸꦱ꧀ꦠꦲꦂ;laterBendara Raden Mas Antawiryaꦧꦼꦤ꧀ꦢꦫꦫꦢꦺꦤ꧀ꦩꦱ꧀ꦲꦤ꧀ꦠꦮꦶꦂꦪ;11 November 1785 – 8 January 1855),[1]also known asDipanegara,was aJavaneseprince who opposed the Dutchcolonialrule. The eldest son of theYogyakarta SultanHamengkubuwono III,he played an important role in theJava Warbetween 1825 and 1830. After his defeat and capture, he was exiled toMakassar,where he died at 69 years old.

His five-year struggle against the Dutch control ofJavahas become celebrated byIndonesiansthroughout the years, acting as a source of inspiration for the fighters in theIndonesian National Revolutionand nationalism in modern-day Indonesia among others.[2]He is a national hero in Indonesia.[3]

Early life[edit]

(CollectionLeiden University Library)

Diponegoro was born on 11 November 1785 inYogyakarta,and was the eldest son of SultanHamengkubuwono IIIof Yogyakarta. During his youth at the Yogyakarta court, major occurrences such as the dissolution of theVOC,theBritish invasion of Java,and the subsequent return to Dutch rule took place. During the invasion, SultanHamengkubuwono IIIpushed aside his power in 1810 in favor of Diponegoro's father and used the general disruption to regain control. In 1812 however, he was once more removed from the throne and exiled off-Java by the British forces. In this process, Diponegoro acted as an adviser to his father and provided aid to the British forces to the point whereRafflesoffered him theSultantitle which he declined, perhaps because his father was still reigning.[2]: 425–426

When the sultan died in 1814, Diponegoro was passed over for the succession to the throne in favor of his younger half-brother,Hamengkubuwono IV(r. 1814–1821), who was supported by the Dutch despite the late Sultan's urging for Diponegoro to be the next Sultan. Being a devout Muslim, Diponegoro was alarmed by the rela xing of religious observance at his half-brother's court in contrast with his own life of seclusion, as well as by the court's pro-Dutch policy.[2]: 427

In 1821, famine and plague spread in Java. Hamengkubuwono IV died in 1822 under mysterious circumstances, leaving only an infant son as his heir. When the year-old boy was appointed as SultanHamengkubuwono V,there was a dispute over his guardianship. Diponegoro was again passed over, though he believed he had been promised the right to succeed his half-brother – even though such a succession was illegal under Islamic rules.[4][2]: 427 This series of natural disasters and political upheavals finally erupted into full-scale rebellion.[5]

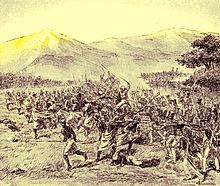

Fighting against the Dutch[edit]

Dutch colonial rule was becoming unpopular among local farmers because of tax rises and crop failures, and among Javanese nobles because the Dutch colonial authorities deprived them of their right to lease land. Diponegoro was widely believed to be theRatu Adil,the just ruler predicted in thePralembang Jayabaya.[6]: 52 Mount Merapi's eruption in 1822 and a cholera epidemic in 1824 furthered the view that a cataclysm was imminent, eliciting widespread support for Diponegoro.[7]: 603

In the days leading up to the war's outbreak, no action was taken by local Dutch officials although rumors of his upcoming insurrection had been floating about. Prophesies and stories, ranging from visions at the tomb of Banten's formerSultan Ageng Tirtayasaalleged to be the ghost of Sultan Agung (the first Sultan of Mataram, predecessor of the Yogyakarta and Surakarta sultanates) to Diponegoro's contact withNyai Roro Kidul,spread across the populace.[2]

The beginning of the war saw large losses on the side of the Dutch, due to their lack of coherent strategy and commitment in fighting Diponegoro'sguerrilla warfare.Ambushes were set up, and food supplies were denied to the Dutch troops. The Dutch finally committed themselves to control the spreading rebellion by increasing the number of troops and sendingGeneral De Kockto stop the insurgency. De Kock developed a strategy of fortified camps (benteng) and mobile forces. Heavily fortified and well-defended soldiers occupied key landmarks to limit the movement of Diponegoro's troops while mobile forces tried to find and fight the rebels. From 1829, Diponegoro definitively lost the initiative and he was put in a defensive position; first inUngaran,then in the palace of the Resident in Semarang, before finally retreating toBatavia.Many troops and leaders were defeated or deserted.

Capture and exile[edit]

In 1830 Diponegoro's military was as good as beaten and negotiations were started. Diponegoro demanded to have a free state under a sultan and wanted to become the Muslim leader (caliph) for the whole of Java. In March 1830 he was invited to negotiate under a flag of truce. He accepted and met at the town ofMagelangbut was taken prisoner on 28 March despite the flag of truce. De Kock claims that he had warned several Javanese nobles to tell Diponegoro he had to lessen his previous demands or that he would be forced to take other measures.[8]

Circumstances of Diponegoro's arrest were seen differently by himself and the Dutch. The former saw the arrest as a betrayal due to the flag of truce, while the latter declared that he had surrendered. The imagery of the event, by JavaneseRaden Salehand DutchNicolaas Pieneman,depicted Diponegoro differently – the former visualizing him as a defiant victim, the latter as a subjugated man.[9]Immediately after his arrest, he was taken toSemarangand later toBatavia,where he was detained at the basement of what is today theJakarta History Museum.In 1830, he was taken toManado,Sulawesiby ship.[10]

After several years inManado,he was moved toMakassarin July 1833 where he was kept withinFort Rotterdamdue to the Dutch believing that the prison was not strong enough to contain him. Despite his prisoner status, his wife Ratnaningsih and some of his followers accompanied him into exile, and he received high-profile visitors, including 16-year-old DutchPrince Henryin 1837. Diponegoro also composed manuscripts on Javanese history and wrote his autobiography,Babad Diponegoro,during his exile. His physical health deteriorated due to old age, and he died on 8 January 1855, at 69 years old.[10][11][12]

Before he died, Diponegoro had mandated that he wanted to be buried inKampung Melayu,a neighborhood then inhabited by the Chinese and the Dutch. This was followed with the Dutch donating1.5 ha (3+3⁄4acres) of land for his graveyard which today has shrunk to just 550 square meters (5,900 square feet). ft.). Later, his wife and followers were also buried in the same complex.[10]His tomb is today visited by pilgrims – often military officers and politicians.[13]

Legacy[edit]

Diponegoro's dynastywould survive to the present day, with their sultans holding secular powers as the governors ofthe Special Region of Yogyakarta.In 1969, a large monumentSasana Wiratamawas erected in Tegalrejo, inYogyakartacity's perimeter, with sponsorship from the military where Diponegoro's palace was believed to have stood, although at that time there was little to show for such a building.[14] In 1973, under the presidency ofSuharto,Diponegoro was made aNational Hero of Indonesia.[3]

Kodam IV/Diponegoro,Indonesian Armyregional command for the Central Java Military Region, is named after him. TheIndonesian Navyhas two ships named after him. The first of these wasKRIDiponegoro(306),aSkoryy-classdestroyercommissioned in 1964 and retired in 1973.[15]The second ship isKRIDiponegoro(365),the lead ship ofDiponegoro-classcorvettepurchased from the Netherlands.Diponegoro UniversityinSemarangwas also named after him, along with many major roads in Indonesian cities. Diponegoro is also depicted in Javanese stanzas,wayang,and performing arts, including self-authoredBabad Diponegoro.[16]

The militancy of people's resistance in Java would rise again during theIndonesian Revolution,which saw the country gain independence from the Netherlands.[17]Early Islamist political parties in Indonesia, such as theMasyumi,portrayed Diponegoro'sjihadas a part of the Indonesian national struggle and by extension Islam as a prominent player in the formation of the country.[18]

During the Royal Netherlands state visit to Indonesia in March 2020, KingWillem-Alexanderoffered thekris of Prince Diponegoroto Indonesia, received by PresidentJoko Widodo.[19]His kris was long considered lost but has now been found, after being identified by theDutch National Museum of Ethnologyin Leiden. The kris of Prince Diponegoro represents a historic importance, as a symbol of Indonesian heroic resilience and the nation's struggle for independence. The extraordinary gold-inlaid Javanese dagger previously was held as the Dutch state collectionin and is now part of the collection of theIndonesian National Museum.[20]There is great doubt whether the Kris is the original Kris of Dipenegoro. Experts think not.[21]

References[edit]

- ^"Sasana Wiratama: Commemorating The Struggle of Prince Diponegro".Retrieved28 September2014.

- ^abcdevan der Kroef, Justus M. (August 1949). "Prince Diponegoro: Progenitor of Indonesian Nationalism".The Far Eastern Quarterly.8(4): 424–450.doi:10.2307/2049542.JSTOR2049542.S2CID161852159.

- ^ab"Daftar Nama Pahlawan Nasional Republik Indonesia (1)"(in Indonesian). Sekretariat Negara Indonesia. Archived fromthe originalon 14 April 2012.Retrieved9 May2012.

- ^"Diponegoro – MSN Encarta".Archived fromthe originalon 2009-11-01.

- ^Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (1993).A history of modern Indonesia since c. 1300.Stanford University Press. p. 115.ISBN978-0-8047-2194-3.[permanent dead link]

- ^Carey, Peter (1976). "The origins of the Java War (1825–30)".The English Historical Review.XCI(CCCLVIII): 52–78.doi:10.1093/ehr/XCI.CCCLVIII.52.

- ^Carey, Peter (2007).The power of prophecy: Prince Dipanagara and the end of an old order in Java, 1785–1855(2nd ed.). Leiden: KITLV Press.ISBN9789067183031.

- ^"Knooppunt Leidse Geschieddidactiek".Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2009.Retrieved28 September2014.

- ^Fotouhi, Sanaz; Zeiny, Esmail (2017).Seen and Unseen: Visual Cultures of Imperialism.Brill. p. 25.ISBN9789004357013.Retrieved25 November2017.

- ^abc"The Resting Place of Indonesian Great Diponegoro".Jakarta Globe.9 February 2013.Retrieved25 November2017.

- ^Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003).Indonesia: Peoples and Histories.Yale University Press. p.235.ISBN0300097093.Retrieved25 November2017.

- ^Said, SM (18 April 2016)."Hari-hari Terakhir Pangeran Diponegoro di Pengasingan".Seputar Indonesia.Retrieved25 November2017.

- ^Zakaria, Anang (30 June 2015)."DPRD Yogya Ziarah ke Makam Diponegoro di Makassar".Tempo(in Indonesian).Retrieved25 November2017.

- ^Anderson, Benedict R. O'G (2006).Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia.Equinox Publishing. p. 179.ISBN9789793780405.Retrieved25 November2017.

- ^"Destroyer Pylkiy Project 30bis / Skoryy Class".kchf.ru.Retrieved26 April2021.

- ^Sumarsam (2013).Javanese Gamelan and the West.University Rochester Press. pp. 65–73.ISBN9781580464451.

- ^Simatupang, T. B. (2009).Report from Banaran: Experiences During the People's War.Equinox Publishing.ISBN9786028397551.

- ^Madinier, Remy (2015).Islam and Politics in Indonesia: The Masyumi Party between Democracy and Integralism.NUS Press. p. 9.ISBN9789971698430.

- ^Yuliasri Perdani; Ardila Syakriah."Prince Diponegoro's kris returned ahead of Dutch royal visit".The Jakarta Post.Retrieved2020-04-05.

- ^Zaken, Ministerie van Buitenlandse (2020-03-10)."The 'kris' of Prince Diponegoro returned to Indonesia – News item – netherlandsandyou.nl".netherlandsandyou.nl.Retrieved2020-04-05.

- ^"Indonesische experts: Nederland gaf de verkeerde kris terug".21 April 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Carey, P.B.R.Babad Dipanagara: an account of the outbreak of the Java War (1825–30): the Surakarta court version of the Babad DipanagaraKuala Lumpur: Printed for the Council of the M.B.R.A.S. by Art Printing Works, 1981. Monograph (Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Malaysian Branch); no.9.

- Sagimun M. D.Pangeran Dipanegara: pahlawan nasionalJakarta: Proyek Biografi Pahlawan Nasional, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 1976. (Indonesian language)

- Yamin, M.Sedjarah peperangan Dipanegara: pahlawan kemerdekaan IndonesiaJakarta: Pembangunan, 1950. (Indonesian language)