Projector

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(January 2023) |

Aprojectororimage projectoris anopticaldevice that projects animage(or moving images) onto a surface, commonly aprojection screen.Most projectors create an image by shining a light through a small transparent lens, but some newer types of projectors can project the image directly, by usinglasers.Avirtual retinal display,or retinal projector, is a projector that projects an image directly on theretinainstead of using an external projection screen.

El 28 de diciembre de 1895 los hermanos Lumière revolucionaron el concepto de ocio y espectáculo. Ese día tuvo lugar en el Salon Indien del Gran Café de París la primera proyección cinematográfica pública y de pago.

The most common type of projector used today is called avideo projector.Video projectors are digital replacements for earlier types of projectors such asslide projectorsandoverhead projectors.These earlier types of projectors were mostly replaced with digital video projectors throughout the 1990s and early 2000s,[1]but old analog projectors are still used at some places. The newest types of projectors arehandheld projectorsthat uselasersorLEDsto project images.

Movie theatersused a type of projector called amovie projector,nowadays mostly replaced withdigital cinemavideo projectors.

Different projector types

[edit]Projectors can be roughly divided into three categories, based on the type of input. Some of the listed projectors were capable of projecting several types of input. For instance: video projectors were basically developed for the projection of prerecorded moving images, but are regularly used for still images inPowerPointpresentations and can easily be connected to a video camera for real-time input. Themagic lanternis best known for the projection of still images, but was capable of projecting moving images from mechanical slides since its invention and was probably at its peak of popularity when used inphantasmagoriashows to project moving images of ghosts.

Real-time

[edit]Still images

[edit]- Slide projector

- Magic lantern

- Magic mirror

- Steganographic mirror (see below for details)

- Enlarger(not for direct viewing, but for the production of photographic prints)

Moving images

[edit]- Movie projector

- Mini portable home theatres projector[2]

- Video projector

- Handheld projector

- Virtual retinal display

- Revolving lanterns (see below for details)

History

[edit]There probably existed quite a few other types of projectors than the examples described below, but evidence is scarce and reports are often unclear about their nature. Spectators did not always provide the details needed to differentiate between for instance ashadow playand alantern projection.Many did not understand the nature of what they had seen and few had ever seen other comparable media. Projections were often presented or perceived as magic or even as religious experiences, with mostprojectionistsunwilling to share their secrets.Joseph Needhamsums up some possible projection examples from China in his 1962 book seriesScience and Civilization in China[3]

Prehistory to 1100

[edit]Shadow play

[edit]The earliest projection of images was most likely done in primitiveshadowgraphydating back to prehistory. Shadow play usually does not involve a projection device, but can be seen as a first step in the development of projectors. It evolved into more refined forms ofshadow puppetryin Asia, where it has a long history in Indonesia (records relating toWayangsince 840 CE), Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, China (records since around 1000 CE), India and Nepal.

Camera obscura

[edit]

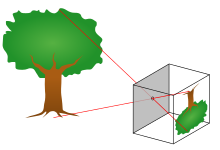

Projectors share a common history withcamerasin thecamera obscura.Camera obscura (Latinfor "dark room" ) is the natural optical phenomenon that occurs when an image of a scene at the other side of a screen (or for instance a wall) is projected through a small hole in that screen to form an inverted image (left to right and upside down) on a surface opposite to the opening. The oldest known record of this principle is a description byHan ChinesephilosopherMozi(ca. 470 to ca. 391 BC). Mozi correctly asserted that the camera obscura image is inverted becauselighttravels in straight lines.[citation needed]

In the early 11th century,Arab physicistIbn al-Haytham(Alhazen) described experiments with light through a small opening in a darkened room and realized that a smaller hole provided a sharper image.[citation needed]

Chinese magic mirrors

[edit]The oldest known objects that can project images areChinese magic mirrors.The origins of these mirrors have been traced back to the ChineseHan dynasty(206 BC – 24 AD)[4]and are also found in Japan. The mirrors were cast in bronze with a pattern em Boss ed at the back and amercuryamalgam laid over the polished front. The pattern on the back of the mirror is seen in a projection when light is reflected from the polished front onto a wall or other surface. No trace of the pattern can be discerned on the reflecting surface with the naked eye, but minute undulations on the surface are introduced during the manufacturing process and cause the reflected rays of light to form the pattern.[5]It is very likely that the practice of image projection via drawings or text on the surface of mirrors predates the very refined ancient art of the magic mirrors, but no evidence seems to be available.

Revolving lanterns

[edit]Revolving lanterns have been known in China as "trotting horse lamps" [ đèn kéo quân ] since before 1000 CE. A trotting horse lamp is a hexagonal, cubical or round lantern which on the inside has cut-outsilhouettesattached to a shaft with a paper vane impeller on top, rotated by heated air rising from a lamp. The silhouettes are projected on the thin paper sides of the lantern and appear to chase each other. Some versions showed some extra motion in the heads, feet and/or hands of figures by connecting them with a fine iron wire to an extra inner layer that would be triggered by a transversely connected iron wire.[6]The lamp would typically show images of horses and horse-riders.

In France, similar lanterns were known as "lanterne vive" (brightorliving lantern) in Medieval times. and as "lanterne tournante" since the 18th century. An early variation was described in 1584 byJean Prevostin his smalloctavobookLa Premiere partie des subtiles et plaisantes inventions.In his "lanterne", cut-out figures of a small army were placed on a wooden platform rotated by a cardboard propeller above a candle. The figures cast their shadows on translucent, oiled paper on the outside of the lantern. He suggested to take special care that the figures look lively: with horses raising their front legs as if they were jumping and soldiers with drawn swords, a dog chasing a hare, etcetera. According to Prevost barbers were skilled in this art and it was common to see these night lanterns in their shop windows.[7]

A more common version had the figures, usually representing grotesque or devilish creatures, painted on a transparent strip. The strip was rotated inside a cylinder by a tin impeller above a candle. The cylinder could be made of paper or of sheet metal perforated with decorative patterns. Around 1608Mathurin Régniermentioned the device in hisSatire XIas something used by apatissierto amuse children.[8]Régnier compared the mind of an old nagger with the lantern's effect of birds, monkeys, elephants, dogs, cats, hares, foxes and many strange beasts chasing each other.[9]

John Locke(1632-1704) referred to a similar device when wondering if ideas are formed in the human mind at regular intervals, "not much unlike the images in the inside of a lantern, turned round by the heat of a candle." Related constructions were commonly used as Christmas decorations in England[10]and parts of Europe. A still relatively common type of rotating device that is closely related does not really involve light and shadows, but it simply uses candles and an impeller to rotate a ring with tiny figurines standing on top.

Many modern electric versions of this type of lantern use all kinds of colorful transparent cellophane figures which are projected across the walls, especially popular for nurseries.

1100 to 1500

[edit]Concave mirrors

[edit]The invertedreal imageof an object reflected by aconcave mirrorcan appear at the focal point in front of the mirror.[11]In a construction with an object at the bottom of two opposing concave mirrors (parabolic reflectors) on top of each other, the top one with an opening in its center, the reflected image can appear at the opening as a very convincing 3D optical illusion.[12]

The earliest description of projection with concave mirrors has been traced back to a text by French authorJean de Meunin his part ofRoman de la Rose(circa 1275).[13]A theory known as theHockney-Falco thesisclaims that artists used either concave mirrors or refractive lenses to project images onto their canvas/board as a drawing/painting aid as early as circa 1430.[14]

It has also been thought that some encounters with spirits or gods since antiquity may have been conjured up with (concave) mirrors.[15]

Fontana's lantern

[edit]

Around 1420 the Venetian scholar and engineerGiovanni Fontanaincluded a drawing of a person with a lantern projecting an image of a demon in his book about mechanical instruments "Bellicorum Instrumentorum Liber".[16]The Latin text "Apparentia nocturna ad terrorem videntium" (Nocturnal appearance to frighten spectators) "clarifies its purpose, but the meaning of the undecipherable other lines is unclear. The lantern seems to simply have the light of an oil lamp or candle go through a transparent cylindrical case on which the figure is drawn to project the larger image, so it probably could not project an image as clearly defined as Fontana's drawing suggests.

Possible 15th century image projector

[edit]In 1437 Italian humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher andcryptographerLeon Battista Albertiis thought to have possibly projected painted pictures from a small closed box with a small hole, but it is unclear whether this actually was a projector or rather a type of show box with transparent pictures illuminated from behind and viewed through the hole.[17]

1500 to 1700

[edit]16th to early 17th century

[edit]Leonardo da Vinciis thought to have had a projecting lantern - with a condensing lens, candle and chimney - based on a small sketch from around 1515.[18]

In hisThree Books of Occult Philosophy(1531-1533)Heinrich Cornelius Agrippaclaimed that it was possible to project "images artificially painted, or written letters" onto the surface of the Moon with the means of moonbeams and their "resemblances being multiplied in the air".Pythagoraswould have often performed this trick.[19]

In 1589Giambattista della Portapublished about the ancient art of projecting mirror writing in his bookMagia Naturalis.[20][21]

Dutch inventorCornelis Drebbel,who is a likely inventor of the microscope, is thought to have had some kind of projector that he used in magical performances. In a 1608 letter he described the many marvelous transformations he performed and the apparitions that he summoned by the means of his new invention based on optics. It included giants that rose from the earth and moved all their limbs very lifelike.[22]The letter was found in the papers of his friendConstantijn Huygens,father of the likely inventor of the magic lanternChristiaan Huygens.

Helioscope

[edit]

In 1612 Italian mathematicianBenedetto Castelliwrote to his mentor, the Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, philosopher and mathematicianGalileo Galileiabout projecting images of the sun through atelescope(invented in 1608) to study the recently discovered sunspots. Galilei wrote about Castelli's technique to the German Jesuit priest, physicist and astronomer Christoph Scheiner.[23]

From 1612 to at least 1630Christoph Scheinerwould keep on studying sunspots and constructing new telescopic solar projection systems. He called these "Heliotropii Telioscopici", later contracted tohelioscope.[23]

Steganographic mirror

[edit]

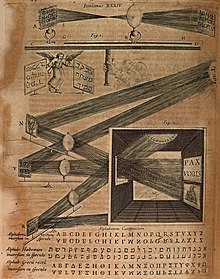

The 1645 first edition of German Jesuit scholarAthanasius Kircher's bookArs Magna Lucis et Umbraeincluded a description of his invention, thesteganographicmirror: a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight, mostly intended for long distance communication. He saw limitations in the increase of size and diminished clarity over a long distance and expressed his hope that someone would find a method to improve on this.[24]Kircher also suggested projecting live flies and shadow puppets from the surface of the mirror.[25]The book was quite influential and inspired many scholars, probably including Christiaan Huygens who would invent the magic lantern. Kircher was often credited as the inventor of the magic lantern, although in his 1671 edition ofArs Magna Lucis et UmbraeKircher himself credited Danish mathematician Thomas Rasmussen Walgensten for the magic lantern, which Kircher saw as a further development of his own projection system.[26][27]

Although Athanasius Kircher claimed the Steganographic mirror as his own invention and wrote not to have read about anything like it,[27]it has been suggested that Rembrandt's 1635 painting of "Belshazzar's Feast"depicts a steganographic mirror projection with God's hand writing Hebrew letters on a dusty mirror's surface.[28]

In 1654 Belgian Jesuit mathematicianAndré Tacquetused Kircher's technique to show the journey from China to Belgium of Italian Jesuit missionaryMartino Martini.[29]It is sometimes reported that Martini lectured throughout Europe with a magic lantern which he might have imported from China, but there's no evidence that anything other than Kircher's technique was used.

Magic lantern

[edit]By 1659 Dutch scientistChristiaan Huygenshad developed the magic lantern, which used a concave mirror to reflect and direct as much of the light of a lamp as possible through a small sheet of glass on which was the image to be projected, and onward into a focusing lens at the front of the apparatus to project the image onto a wall or screen (Huygens apparatus actually used two additional lenses). He did not publish nor publicly demonstrate his invention as he thought it was too frivolous.

The magic lantern became a very popular medium for entertainment and educational purposes in the 18th and 19th century. This popularity waned after the introduction of cinema in the 1890s. The magic lantern remained a common medium untilslide projectorscame into widespread use during the 1950s.

1700 to 1900

[edit]Solar microscope

[edit]

A few years before his death in 1736 Polish-German-Dutch physicistDaniel Gabriel Fahrenheitreportedly constructed a solar microscope, which basically was a combination of the compound microscope with camera obscura projection. It needed bright sunlight as a light source to project a clear magnified image of transparent objects. Fahrenheit's instrument may have been seen by German physicianJohann Nathanael Lieberkühnwho introduced the instrument in England, where opticianJohn Cuffimproved it with a stationary optical tube and an adjustable mirror.[30]In 1774 English instrument makerBenjamin Martinintroduced his "Opake Solar Microscope" for the enlarged projection of opaque objects. He claimed:

TheOpake Microsc[o]pe,not only magnifies the natural Appearance or Size of Objects of every Sort, but at the ſame time throws ſuch a Quantity of Solar Rays upon them, as to make all their Colours appear vaſtly more vivid and ſtrong than to the naked Eye; and their Parts ſo expanded and diſtinct upon a fixed Screen, that they are not only viewed with the utmoſt Pleaſure, but may be drawn with the greateſt Eaſe by any ingenious Hand. "[31]

The solar microscope,[32]was employed in experiments with photosensitivesilver nitratebyThomas Wedgwoodin collaboration withHumphry Davyin making the first, but impermanent, photographic enlargements. Their discoveries, regarded as the earliest deliberate and successful form of photography, were published in June 1802 by Davy in hisAn Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Invented by T. Wedgwood, Esq. With Observations by H. Davyin the first issue of theJournals of the Royal Institution of Great Britain.[33][34]

Opaque projectors

[edit]

Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, logician and engineerLeonhard Eulerdemonstrated anopaque projector,now commonly known as an episcope, around 1756. It could project a clear image of opaque images and (small) objects.[35]

French scientistJacques Charlesis thought to have invented the similar "megascope" in 1780. He used it for his lectures.[36]Around 1872Henry Mortonused an opaque projector in demonstrations for huge audiences, for example in the Philadelphia Opera House which could seat 3500 people. His machine did not use a condenser or reflector, but used anoxyhydrogenlamp close to the object in order to project huge clear images.[37]

Solar camera

[edit]See main article:Solar camera

Known equally, though later, as a solar enlarger, thesolar camerais a photographic application of the solar microscope and an ancestor of the darkroomenlarger,and was used, mostly by portrait photographers and as an aid to portrait artists, in the mid-to-late 19th century[38]to make photographic enlargements from negatives using the Sun as a light source powerful enough to expose the then available low-sensitivity photographic materials. It was superseded in the 1880s when other light sources, including theincandescent bulb,were developed for the darkroom enlarger and materials became ever more photo-sensitive.[32][39]

20th century to present day

[edit]

In the early and middle parts of the 20th century, low-cost opaque projectors were produced and marketed as a toy for children. The light source in early opaque projectors was oftenlimelight,withincandescent light bulbsandhalogen lampstaking over later. Episcopes are still marketed as artists' enlargement tools to allow images to be traced on surfaces such as prepared canvas.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s,overhead projectorsbegan to be widely used in schools and businesses. The first overhead projector was used for police identification work.[citation needed]It used a celluloid roll over a 9-inch stage allowing facial characteristics to be rolled across the stage. The United States military in 1940 was the first to use it in quantity for training.[40][41][42][43]

From the 1950s to the 1990sslide projectorsfor 35 mm photographic positive film slides were common for presentations and as a form of entertainment; family members and friends would occasionally gather to view slideshows, typically of vacation travels.[44]

ComplexMulti-imageshows of the 1970s to 1990s, purposed usually for marketing, promotion or community service or artistic displays, used35mmand 46mm transparencyslides(diapositives) projected by single or multipleslide projectorsonto one or more screens in synchronization with anaudiovoice-overand/or music track controlled by a pulsed-signal tape or cassette.[45]Multi-image productions are also known as multi-image slide presentations,slide showsand diaporamas and are a specific form ofmultimediaoraudio-visualproduction.

Digital camerashad become commercialised by 1990, and in 1997Microsoft PowerPointwas updated to include image files,[46]accelerating the transition from 35 mm slides to digital images, and thus digital projectors, in pedagogy and training.[47]Production of all Kodak Carousel slide projectors ceased in 2004,[48]and in 2009 manufacture and processing of Kodachrome film was discontinued.[49]

In popular culture

[edit]InMad Men's first seriesthe final episode presents the protagonist Don Draper's presentation (via slide projector) of a plan to market the Kodak slide carrier a 'carousel'.[44]

See also

[edit]- Planetarium projector

- Projector phone

- Hockney-Falco thesis

- Slide show

- Multi-image

- Enlarger

- Audio-visual

Notes and references

[edit]- ^"THE ULTIMATE PROJECTOR BUYING GUIDE".ProjectorScreen.Retrieved27 April2022.

- ^Bano, Maira (16 September 2022)."What are the 5 basic types of projectors? An easy guide".projectorsfocus.

- ^Needham, Joseph.Science and Civilization in China, vol. IV, part 1: Physics and Physical Technology(PDF).pp. 122–124. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2017-07-03.Retrieved2016-08-30.

- ^Mak, Se-yuen; Yip, Din-yan (2001). "Secrets of the Chinese magic mirror replica".Physics Education.36(2): 102–107.Bibcode:2001PhyEd..36..102M.doi:10.1088/0031-9120/36/2/302.S2CID250800685.

- ^"Oriental magic mirrors and the Laplacian image"Archived2014-12-19 at theWayback Machineby Michael Berry, Eur. J. Phys. 27 (2006) 109–118, DOI: 10.1088/0143-0807/27/1/012

- ^Yongxiang Lu (2014-10-20).A History of Chinese Science and Technology, Volume 3.Springer. pp. 308–310.ISBN9783662441633.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-10-22.

- ^Prevost, I. (de Toulouse) Auteur du texte (1584).La Première partie des subtiles et plaisantes inventions, comprenant plusieurs jeux de récréation et traicts de soupplesse, par le discours desquels les impostures des bateleurs sont descouvertes. Composé par I. Prevost,...

- ^Laurent MannoniLe grand art de la lumiere et de l'ombre(1995) p. 37-38

- ^"Les satyres et autres oeuvres de regnier avec des remarques".1730.

- ^S. AlexanderLocke's LanterninMind(1929)

- ^Gbur, Gregory(17 April 2014)."Physics demonstrations: The Phantom Lightbulb".Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2017.

- ^"PhysicsLAB: Demonstration: Real Images".Archivedfrom the original on 2017-02-02.

- ^"Rose -".Archivedfrom the original on 2016-09-16.

- ^"Art Optics -".Archivedfrom the original on 2016-09-11.

- ^Ruffles, Tom (2004-09-27).Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife.McFarland. pp. 15–17.ISBN9780786420056.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-11-07.

- ^Fontana, Giovanni (1420)."Bellicorum instrumentorum liber".p. 144.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-09-18.

- ^"Camera Obscura - Encyclopedia".Archivedfrom the original on 2016-10-22.

- ^"The History of The Discovery of Cinematography - 1400 - 1599".Archivedfrom the original on 2018-01-31.

- ^Agrippa (1993).Three Books of Occult Philosophy.Llewellyn Worldwide.ISBN9780875428321.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-21.

- ^"An Introduction to Lantern History: The Magic Lantern Society".Archived fromthe originalon 2017-07-21.Retrieved2017-09-19.

- ^"Natural magick".1658.

- ^Drebbel, Cornelis (1608)."brief aan Ysbrandt van Rietwijck"(PDF)(in Dutch).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2016-10-05.

- ^abWhitehouse, David (2004).The Sun: A Biography.Orion.ISBN9781474601092.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-10-05.

- ^Kircher, Athanasius (1645).Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae.p. 912.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-12.

- ^Gorman, Michael John (2007).Inside the Camera Obscura(PDF).p. 44.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2017-12-22.

- ^Rendel, Mats."about Athanasius Kircher".Archivedfrom the original on 2008-02-20.

- ^abRendel, Mats."About the Construction of The Magic Lantern, or The Sorcerers Lamp".Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-27.

- ^Vermeir, Koen (2005).The magic of the magic lantern(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ^"De zeventiende eeuw. Jaargang 10"(in Dutch and Latin).Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-04.

- ^S. Bradbury (2014).The Evolution of the Microscope.Elsevier. pp. 152–160.ISBN9781483164328.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-01-16.

- ^Martin, Benjamin (1774).The Description and Use of an Opake Solar Microscope.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-08-01.

- ^abFocal encyclopedia of photography: digital imaging, theory and applications, history, and science.Peres, Michael R. (4th ed.). Amsterdam: Focal. 2007.ISBN978-0-08-047784-8.OCLC499055803.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^Photography, essays & images: illustrated readings in the history of photography.Newhall, Beaumont, 1908-1993. New York: Museum of Modern Art. 1980.ISBN0-87070-385-4.OCLC7550618.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^International Congress: Pioneers of Photographic Science and Technology (1st: 1986: International Museum of Photography); Ostroff, Eugene; SPSE—the Society for Imaging Science and Technology (1987),Pioneers of photography: their achievements in science and technology,SPSE—The Society for Imaging Science and Technology; [Boston, Mass.]: Distributed by Northeastern University Press,ISBN978-0-89208-131-8

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Euler, Leonhard (1773).Briefe an eine deutsche Prinzessinn über verschiedene Gegenstände aus der Physik und Philosophie - Zweyter Theil(in German). pp. 192–196.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-01-16.

- ^Hankins, Silverman (2014).Instruments and the Imagination.Princeton University Press.ISBN9781400864119.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-01-16.

- ^Moigno's, François (1872).L'art des projections.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-02-09.

- ^David A. Woodward, of Baltimore, Maryland, "Solar Camera", Specification forming part of Letters Patent No. 16,700, dated February 24, 1857 Reissue No. 2,311, dated July 10, 1866, viaLuminous_Lint

- ^Hannavy, John (2013-12-16). Hannavy, John (ed.).Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography.doi:10.4324/9780203941782.ISBN9780203941782.

- ^"Local Preparation of Training Aids",Naval Training Bulletin,March 1949, p.31

- ^"Local Preparation of Training Aids",Naval Training Bulletin,July 1949, p.2

- ^"Transparencies made to order",Naval Training Bulletin,July 1951, p.17–19

- ^"Local Preparations – 20th Century",Naval Training Bulletin,July 1951, p.14–17

- ^abIrene V. Small, "Against Depth: Looking at the surface through the Kodak Carousel" in Kaganovsky, L., Goodlad, L. M. E., Rushing, R. A. (2013).Mad Men, Mad World: Sex, Politics, Style, and the 1960s.United Kingdom: Duke University Press.

- ^Bano, Maira (28 June 2024)."Can All Projectors Do Rear Projection".projectorsfocus.

- ^Gaskins, R. (2012). Sweating Bullets: Notes about Inventing PowerPoint. United States: Vinland Books.

- ^Kohl, Allan T. “Revisioning Art History: how a century of change in imaging technologies helped to shape a discipline.” (2012)

- ^The Routledge Companion to Media Technology and Obsolescence. (2018). United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- ^Cortez, Meghan B. (September 2016)."Kodak Carousel Projectors Revolutionized the Lecture".EdTech Focus on Higher Education.RetrievedApril 1,2021.