Putto

Aputto(Italian:[ˈputto];pluralputti[ˈputti])[1]is a figure in a work of art depicted as a chubby male child, usually naked and very often winged. Originally limited to profanepassionsin symbolism,[2]the putto came to represent a sort of babyangelin religious art, often calledcherubs(plural cherubim), though in traditional Christian theology a cherub is actually one of the most senior types of angel.[3]

The same figures were also seen in representations ofclassical myth,and increasingly in general decorative art. InBaroque artthe putto came to represent theomnipresenceofGod.[2]A putto representing acupidis also called anamorino(pluralamorini) oramoretto(pluralamoretti).

Etymology

[edit]

The more commonly found formputtiis the plural of the Italian wordputto.The Italian word comes from the Latin wordputus,meaning "boy" or "child".[4]Today, in Italian,puttomeans either toddler winged angel or, rarely, toddler boy. It may have been derived from the same Indo-European root as the Sanskrit word "putra" (meaning "boy child", as opposed to "son" ), Avestanpuθra-, Old Persianpuça-, Pahlavi (Middle Persian)pusandpusar,all meaning "son", and the New Persianpesar"boy, son".

History

[edit]

Putti, in the ancient classical world of art, were winged infants that were believed to influence human lives. InRenaissance art,the form of the putto was derived in various ways including theGreekErosorRomanAmor/Cupid,the god of love and companion ofAphroditeorVenus;the Roman,genius,a type of guardian spirit; or sometimes the Greek,daemon,a type of messenger spirit, being halfway between the realms of the human and the divine.[5]

Revival of the putto in the Renaissance

[edit]

Putti are a classical motif found primarily on childsarcophagiof the 2nd century, where they are depicted fighting,dancing,participating inbacchic rites,playingsports,etc.

The putto disappeared during theMiddle Agesand was revived during theQuattrocento.The revival of the figure of the putto is generally attributed toDonatello,inFlorence,in the 1420s, although there are some earlier manifestations (for example thetombofIlaria del Carretto,sculpted byJacopo della QuerciainLucca). Since then, Donatello has been called the originator of the putto because of the contribution to art he made in restoring the classical form of putto. He gave putti a distinct character by infusing the form withChristianmeanings and using it in new contexts such as musicianangels.Putti also began to feature in works showing figures from classical mythology, which became popular in the same period.

Some of Donatello's putti are rather older than the usual toddler type, and also behaving in a less than angelic way. The bronze figure ofAmore-Attisis the most extreme of these. These are often termedspiritelli,sometimes translated as "imps".Older putto-like figures are seen in other art; they are very typical as winged teenage boys in the borders of works by theEmbriachi workshopfrom the years around 1400.

Most Renaissance putti are essentially decorative and they ornament both religious and secular works, without usually taking any actual part in the events depicted in narrative paintings. There are two popular forms of the putto as the main subject of a work of art in 16th-centuryItalian Renaissanceart: the sleeping putto and the standing putto with an animal or other object.[6]

Where putti are found

[edit]Putti,cupids,andangels(see below) can be found in bothreligiousandsecularart from the 1420s in Italy, the turn of the 16th century in theNetherlandsandGermany,theManneristperiod and lateRenaissanceinFrance,and throughoutBaroqueceilingfrescoes.Many artists have depicted them, but among the best-known are the sculptorDonatelloand the painterRaphael.The two relaxed and curious putti who appear at the foot of Raphael'sSistine Madonnaare often reproduced.[7]

They also experienced a major revival in the 19th century, where theygamboledthrough paintings by Frenchacademicpainters, from advertisements toGustave Doré’s illustrations forOrlando Furioso.

Iconography of the putto

[edit]Theiconographyof putti is deliberately unfixed, so that it is difficult to tell the difference between putti, cupids, and various forms of angels. They have no unique, immediately identifiable attributes, so that putti may have many meanings and roles in the context of art.

Some of the more common associations are:

- Associations withAphrodite,and so with romantic—or erotic—love

- Associations with Heaven

- Associations with peace, prosperity, mirth, and leisure

Historiography

[edit]Thehistoriographyof this subject matter is very short. Many art historians have commented on the importance of the putto in art, but few have undertaken a major study. One useful scholarly examination is Charles Dempsey'sInventing the Renaissance Putto.[2]

Gallery

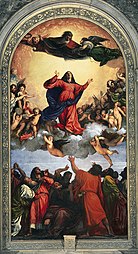

[edit]-

Roman sarcophagus with a procession of drunk putti, which belongs to a child, with a procession of drunk putti, mid-2nd century AD, marble,Neues Museum,Berlin

-

Roman putti on columns of theSarcophagus of Junius Bassus,389, marble,Museo del tesoro di San Pietro,St. Peter's Basilica,Vatican City[8]

-

Gothicmirror frame, by theEmbriachi workshop,1st half of the 15th century, wood, bone, horn and bone marquetry,Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin,Germany

-

Renaissanceputti on a page ofDante'sDivine Comedy,byGherardo di Giovanni del Fora,c.1474-1476, tempera colors, gold paint, gold leaf, and ink on parchment,Bargello,Florence[9]

-

Renaissanceputti on an elaborate fireplace with the crests ofFrançois IandClaude de France,in the Salle du Roi,Château of Blois,Blois,France, unknown architect, 1515-1524

-

Renaissance putti in the Codex Durlach 2, unknown illustrator, 1520, paintedillumination,Baden State Library,Karlsruhe,Germany

-

Baroqueputti on theTomb of Ferdinand van den Eynde,designed and executed byFrançois Duquesnoy,1633–1640, marble,Santa Maria dell'Anima,Rome, Italy

-

Baroque putti painted on theboiserieof a room from theHôtel Colbert de Villacerf,now in theMusée Carnavalet,Paris, unknown architect, sculptor and painter,c.1650[10]

-

Baroquegrotesqueswith putti on a door in theGalerie d'Apollon,Louvre Palace,Paris, byLouis Le VauandCharles Le Brun,after 1661[11]

-

Rococobedroom from theCa' Sagredoin Venice, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, byCarpoforo Mazzetti TencallaandAbbondio Stazio,c.1720 or later

-

The Rape of Europa,byFrançois Boucher,c.1732–1734, oil on canvas,Wallace Collection,London,United Kingdom[12]

-

Rococo relief ofDianawith two putti above the entrance of theAmalienburg,Munich,Germany, designed byFrançois de Cuvilliés,1734–1739

-

Rocococartouchewith putti in the Cabinet de la Pendule,Palace of Versailles,France, created and sculpted byJacques Verberckt,1738[13]

-

Pair of rocococandelabra,by theChelsea porcelain factory,18th century, soft-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of Chinese vases with French Rococo mounts, the vases: early 18th century, the mounts: 1760–1770, hard-paste porcelain with ormolu mounts, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Louis XVI stylefiredogwith putti that warm themselves at a flame, 1780–1790,ormolu,Rijksmuseum,Amsterdam,the Netherlands

-

Louis XVI style candelabrum with putto, late 18th century, gilt and patinated bronze,Musée Jacquemart-André,Paris,France

-

Second Empire style(Louis XVI Revival style) clock, unknown sculptor, dial and mechanism byFerdinand Berthoud,c.1860, gilt bronze,Château de Compiègne,France

-

The Birth of Venus,byWilliam-Adolphe Bouguereau,1879, oil on canvas,Musée d'Orsay,Paris, France

-

Door knocker ofAvenue Kléberno. 21, Paris, France, unknown architect and sculptor,c.1890

-

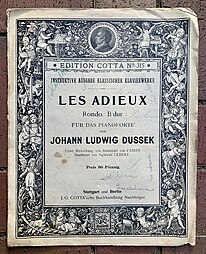

Renaissance Revivalputti on the cover of a magazine with sheets of music byJan Ladislav Dussek,c.1890, ink on paper, private collection

-

Beaux-Artsstreet light with putti, byHenri Désiré Gauquié,c.1896–1900, bronze,Pont Alexandre III,Paris, France

-

Art Nouveauputto, anymphand a nude on an advertising poster for Pétrole Stella, byHenri Gray,1897, coloured lithograph,Library of Congress,Washington, D.C.,US

-

Rococo Revivalpolychromeframe with a putto in a round niche, unknown workshop or designer,c.1900, painted metal, private collection

-

Secessionistputto with twocornucopiaswith floral cascades, byMichael Powolny,designed inc.1907, produced in 1912, ceramic,Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin[14]

-

Beaux Arts putto on the Vasile Urseanu House, the currentBucharest Observatory(Bulevardul Lascăr Catargiuno. 21),Bucharest,Romania, designed byIon D. Berindey,1908–1910[15]

-

Renaissance Revival grotesque with putti on the Doctor Răuțoiu House (Strada Tache Ionescuno. 29), Bucharest, designed byGregoire MarcandErnest Doneaud,c.1910[16]

-

Beaux Artsstuccowith putti on a ceiling inPiața Romanăno. 3, Bucharest, Romania, designed bySiegfired Kofsinskiand C. Crețoiu, 1912

-

Beaux Arts putto on a balcony balustrade of theHôtel Claridge(Avenue des Champs-Élyséesno. 74), designed byCharles LefebvreorLouis Duhayon,1914

-

Art Decoreliefs of putti onRue de Vaugirardno. 60, Paris, France, unknown architect,c.1930

See also

[edit]- Puer Mingens– Artistic depictions of boys urinating

- Four Kumāras– A group of semi-divine sage boys in Hinduism

- Gohō dōji– Buddhist guardian deities in the form of young boys

References

[edit]- ^"arthistory.about".arthistory.about. 2012-04-13. Archived fromthe originalon 2013-04-02.Retrieved2012-12-30.

- ^abcDempsey, Charles.Inventing the Renaissance Putto.University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, 2001.

- ^"cherub".American Heritage Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 4 June 2016.Retrieved24 May2016."British & World English: cherub".OxfordDictionaries.Retrieved24 May2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^Harper, Douglas."putti".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^Struthers, Sally A. "Donatello's 'Putti': Their Genesis, Importance, and Influence on Quattrocento Sculpture and Painting. (Volumes I and II).(PhD Dissertation) "The Ohio State University, 1992. United States – OhioLINK ETD.

- ^Korey, ALexandra M. "Putti, Pleasure, and Pedagogy in Sixteenth-Century Italian Prints and Decorative Arts

."The University of Chicago, 2007. United States – Illinois:ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (PQDT).Web. 23 Oct. 2011.

."The University of Chicago, 2007. United States – Illinois:ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (PQDT).Web. 23 Oct. 2011.

- ^"Loggia".Loggia. Archived fromthe originalon 2014-03-03.Retrieved2012-12-30.

- ^Gombrich, E. H. (2020).Istoria Artei(in Romanian). ART. p. 128.ISBN978-606-710-751-7.

- ^Gombrich, E. H. (2020).Istoria Artei(in Romanian). ART. p. 266.ISBN978-606-710-751-7.

- ^"LAMBRIS DU CABINET DE L'HÔTEL COLBERT DE VILLACERF".carnavalet.paris.fr.Retrieved31 August2023.

- ^Sharman, Ruth (2022).Yves Saint Laurent & Art.Thames & Hudson. p. 147.ISBN978-0-500-02544-4.

- ^"The Rape of Europa / National Galleries of Scotland".Archivedfrom the original on 2020-10-29.Retrieved2020-11-05.

- ^Martin, Henry (1928).La Grammaire des Styles - Le Style Louis XV(in French). Flammarion. p. 61.

- ^Wilhide, Elizabeth (2022).Design - The Whole Story.Thames & Hudson. p. 105.ISBN978-0-500-29687-5.

- ^"Un arhitect pentru secole"(in Romanian).Digi24.29 August 2016.

- ^Ștefan Micu."Casa Rautoiu – arhitect Gregoire Marc (Strada Take Ionescu 29)".bucurestiivechisinoi.ro.Retrieved4 September2023.

![Roman putti on columns of the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, 389, marble, Museo del tesoro di San Pietro, St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City[8]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c7/1058_-_Roma%2C_Museo_d._civilt%C3%A0_Romana_-_Calco_sarcofago_Giunio_Basso_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto%2C_12-Apr-2008_%28cropped%29.jpg/295px-1058_-_Roma%2C_Museo_d._civilt%C3%A0_Romana_-_Calco_sarcofago_Giunio_Basso_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto%2C_12-Apr-2008_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![Renaissance putti on a page of Dante's Divine Comedy, by Gherardo di Giovanni del Fora, c.1474-1476, tempera colors, gold paint, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, Bargello, Florence[9]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Gherardo_Di_Giovanni_-_Illustration_to_a_Missal_-_WGA08671.jpg/175px-Gherardo_Di_Giovanni_-_Illustration_to_a_Missal_-_WGA08671.jpg)

![Baroque putti painted on the boiserie of a room from the Hôtel Colbert de Villacerf, now in the Musée Carnavalet, Paris, unknown architect, sculptor and painter, c. 1650[10]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/H%C3%B4tel_Colbert_de_Villacerf_3.jpg/191px-H%C3%B4tel_Colbert_de_Villacerf_3.jpg)

![Baroque grotesques with putti on a door in the Galerie d'Apollon, Louvre Palace, Paris, by Louis Le Vau and Charles Le Brun, after 1661[11]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3d/Detail_of_the_Galerie_d%27Apollon_%2814%29.jpg/151px-Detail_of_the_Galerie_d%27Apollon_%2814%29.jpg)

![The Rape of Europa, by François Boucher, c.1732–1734, oil on canvas, Wallace Collection, London, United Kingdom[12]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Francois_Boucher_The_Rape_of_Europa.jpg/306px-Francois_Boucher_The_Rape_of_Europa.jpg)

![Rococo cartouche with putti in the Cabinet de la Pendule, Palace of Versailles, France, created and sculpted by Jacques Verberckt,1738[13]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Cabinet_de_la_Pendule._Versailles._05.JPG/383px-Cabinet_de_la_Pendule._Versailles._05.JPG)

![Secessionist putto with two cornucopias with floral cascades, by Michael Powolny, designed in c. 1907, produced in 1912, ceramic, Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin[14]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Michael_powolny_e_bertold_l%C3%B6ffler%2C_putto_con_cornucopia%2C_vienna_1912_ca.jpg/209px-Michael_powolny_e_bertold_l%C3%B6ffler%2C_putto_con_cornucopia%2C_vienna_1912_ca.jpg)

![Beaux Arts putto on the Vasile Urseanu House, the current Bucharest Observatory (Bulevardul Lascăr Catargiu no. 21), Bucharest, Romania, designed by Ion D. Berindey, 1908–1910[15]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/21_Bulevardul_Lasc%C4%83r_Catargiu%2C_Bucharest_%2803%29.jpg/272px-21_Bulevardul_Lasc%C4%83r_Catargiu%2C_Bucharest_%2803%29.jpg)

![Renaissance Revival grotesque with putti on the Doctor Răuțoiu House (Strada Tache Ionescu no. 29), Bucharest, designed by Gregoire Marc and Ernest Doneaud, c. 1910[16]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/29_Strada_Tache_Ionescu%2C_Bucharest_%2802%29.jpg/436px-29_Strada_Tache_Ionescu%2C_Bucharest_%2802%29.jpg)