Quantum gravity

Quantum gravity(QG) is a field oftheoretical physicsthat seeks to describe gravity according to the principles ofquantum mechanics.It deals with environments in which neithergravitationalnor quantum effects can be ignored,[1]such as in the vicinity ofblack holesor similar compact astrophysical objects, such asneutron stars,[2]as well as in the early stages of the universe moments after theBig Bang.[3]

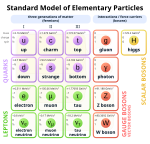

Three of the fourfundamental forcesof nature are described within the framework ofquantum mechanicsandquantum field theory:theelectromagnetic interaction,thestrong force,and theweak force;this leavesgravityas the only interaction that has not been fully accommodated. The current understanding of gravity is based onAlbert Einstein'sgeneral theory of relativity,which incorporates his theory of special relativity and deeply modifies the understanding of concepts like time and space. Although general relativity is highly regarded for its elegance and accuracy, it has limitations: thegravitational singularitiesinsideblack holes,the ad hoc postulation ofdark matter,as well asdark energyand its relation to thecosmological constantare among the current unsolved mysteries regarding gravity,[4]all of which signal the collapse of the general theory of relativity at different scales and highlight the need for a gravitational theory that goes into the quantum realm. At distances close to thePlanck length,like those near the center of the black hole,quantum fluctuationsof spacetime are expected to play an important role.[5]Finally, the discrepancies between the predicted value for thevacuum energyand the observed values (which, depending on considerations, can be of 60 or 120 orders of magnitude)[6][7]highlight the necessity for a quantum theory of gravity.

The field of quantum gravity is actively developing, and theorists are exploring a variety of approaches to the problem of quantum gravity, the most popular beingM-theoryandloop quantum gravity.[8]All of these approaches aim to describe the quantum behavior of thegravitational field,which does not necessarily includeunifying all fundamental interactionsinto a single mathematical framework. However, many approaches to quantum gravity, such asstring theory,try to develop a framework that describes all fundamental forces. Such a theory is often referred to as atheory of everything.Some of the approaches, such as loop quantum gravity, make no such attempt; instead, they make an effort to quantize the gravitational field while it is kept separate from the other forces. Other lesser-known but no less important theories includeCausal dynamical triangulation,Noncommutative geometry,andTwistor theory.[9]

One of the difficulties of formulating a quantum gravity theory is that direct observation of quantum gravitational effects is thought to only appear at length scales near thePlanck scale,around 10−35meters, a scale far smaller, and hence only accessible with far higher energies, than those currently available in high energyparticle accelerators.Therefore, physicists lack experimental data which could distinguish between the competing theories which have been proposed.[n.b. 1][n.b. 2]

Thought experimentapproaches have been suggested as a testing tool for quantum gravity theories.[10][11]In the field of quantum gravity there are several open questions – e.g., it is not known how spin of elementary particles sources gravity, and thought experiments could provide a pathway to explore possible resolutions to these questions,[12]even in the absence of lab experiments or physical observations.

In the early 21st century, new experiment designs and technologies have arisen which suggest that indirect approaches to testing quantum gravity may be feasible over the next few decades.[13][14][15][16]This field of study is calledphenomenological quantum gravity.

Overview[edit]

How can the theory of quantum mechanics be merged with the theory ofgeneral relativity/gravitationalforce and remain correct at microscopic length scales? What verifiable predictions does any theory of quantum gravity make?

Much of the difficulty in meshing these theories at all energy scales comes from the different assumptions that these theories make on how the universe works. General relativity models gravity as curvature ofspacetime:in the slogan ofJohn Archibald Wheeler,"Spacetime tells matter how to move; matter tells spacetime how to curve."[17]On the other hand, quantum field theory is typically formulated in theflatspacetime used inspecial relativity.No theory has yet proven successful in describing the general situation where the dynamics of matter, modeled with quantum mechanics, affect the curvature of spacetime. If one attempts to treat gravity as simply another quantum field, the resulting theory is notrenormalizable.[18]Even in the simpler case where the curvature of spacetime is fixeda priori,developing quantum field theory becomes more mathematically challenging, and many ideas physicists use in quantum field theory on flat spacetime are no longer applicable.[19]

It is widely hoped that a theory of quantum gravity would allow us to understand problems of very high energy and very small dimensions of space, such as the behavior ofblack holes,and theorigin of the universe.[1]

One major obstacle is that forquantum field theory in curved spacetimewith a fixed metric,bosonic/fermionicoperator fieldssupercommuteforspacelike separated points.(This is a way of imposing aprinciple of locality.) However, in quantum gravity, the metric is dynamical, so that whether two points are spacelike separated depends on the state. In fact, they can be in aquantum superpositionof being spacelike and not spacelike separated.[citation needed]

Quantum mechanics and general relativity[edit]

Graviton[edit]

The observation that allfundamental forcesexcept gravity have one or more knownmessenger particlesleads researchers to believe that at least one must exist for gravity. This hypothetical particle is known as thegraviton.These particles act as aforce particlesimilar to thephotonof the electromagnetic interaction. Under mild assumptions, the structure of general relativity requires them to follow the quantum mechanical description of interacting theoretical spin-2 massless particles.[20][21][22][23][24] Many of the accepted notions of a unified theory of physics since the 1970s assume, and to some degree depend upon, the existence of the graviton. TheWeinberg–Witten theoremplaces some constraints on theories in whichthe graviton is a composite particle.[25][26] While gravitons are an important theoretical step in a quantum mechanical description of gravity, they are generally believed to be undetectable because they interact too weakly.[27]

Nonrenormalizability of gravity[edit]

General relativity, likeelectromagnetism,is aclassical field theory.One might expect that, as with electromagnetism, the gravitational force should also have a correspondingquantum field theory.

However, gravity is perturbativelynonrenormalizable.[28][29]For a quantum field theory to be well defined according to this understanding of the subject, it must beasymptotically freeorasymptotically safe.The theory must be characterized by a choice offinitely manyparameters, which could, in principle, be set by experiment. For example, inquantum electrodynamicsthese parameters are the charge and mass of the electron, as measured at a particular energy scale.

On the other hand, in quantizing gravity there are, inperturbation theory,infinitely many independent parameters(counterterm coefficients) needed to define the theory. For a given choice of those parameters, one could make sense of the theory, but since it is impossible to conduct infinite experiments to fix the values of every parameter, it has been argued that one does not, in perturbation theory, have a meaningful physical theory. At low energies, the logic of therenormalization grouptells us that, despite the unknown choices of these infinitely many parameters, quantum gravity will reduce to the usual Einstein theory of general relativity. On the other hand, if we could probe very high energies where quantum effects take over, thenevery oneof the infinitely many unknown parameters would begin to matter, and we could make no predictions at all.[30]

It is conceivable that, in the correct theory of quantum gravity, the infinitely many unknown parameters will reduce to a finite number that can then be measured. One possibility is that normalperturbation theoryis not a reliable guide to the renormalizability of the theory, and that there reallyisaUV fixed pointfor gravity. Since this is a question ofnon-perturbativequantum field theory, finding a reliable answer is difficult, pursued in theasymptotic safety program.Another possibility is that there are new, undiscovered symmetry principles that constrain the parameters and reduce them to a finite set. This is the route taken bystring theory,where all of the excitations of the string essentially manifest themselves as new symmetries.[31][better source needed]

Quantum gravity as an effective field theory[edit]

In aneffective field theory,not all but the first few of the infinite set of parameters in a nonrenormalizable theory are suppressed by huge energy scales and hence can be neglected when computing low-energy effects. Thus, at least in the low-energy regime, the model is a predictive quantum field theory.[32]Furthermore, many theorists argue that the Standard Model should be regarded as an effective field theory itself, with "nonrenormalizable" interactions suppressed by large energy scales and whose effects have consequently not been observed experimentally.[33]

By treating general relativity as aneffective field theory,one can actually make legitimate predictions for quantum gravity, at least for low-energy phenomena. An example is the well-known calculation of the tiny first-order quantum-mechanical correction to the classical Newtonian gravitational potential between two masses.[32]

Spacetime background dependence[edit]

A fundamental lesson of general relativity is that there is no fixed spacetime background, as found inNewtonian mechanicsandspecial relativity;the spacetime geometry is dynamic. While simple to grasp in principle, this is a complex idea to understand about general relativity, and its consequences are profound and not fully explored, even at the classical level. To a certain extent, general relativity can be seen to be arelational theory,[34]in which the only physically relevant information is the relationship between different events in spacetime.

On the other hand, quantum mechanics has depended since its inception on a fixed background (non-dynamic) structure. In the case of quantum mechanics, it is time that is given and not dynamic, just as in Newtonian classical mechanics. In relativistic quantum field theory, just as in classical field theory,Minkowski spacetimeis the fixed background of the theory.

String theory[edit]

String theorycan be seen as a generalization of quantum field theory where instead of point particles, string-like objects propagate in a fixed spacetime background, although the interactions among closed strings give rise tospace-timein a dynamic way. Although string theory had its origins in the study ofquark confinementand not of quantum gravity, it was soon discovered that the string spectrum contains thegraviton,and that "condensation" of certain vibration modes of strings is equivalent to a modification of the original background. In this sense, string perturbation theory exhibits exactly the features one would expect of a perturbation theory that may exhibit a strong dependence on asymptotics (as seen, for example, in theAdS/CFTcorrespondence) which is a weak form ofbackground dependence.

Background independent theories[edit]

Loop quantum gravityis the fruit of an effort to formulate abackground-independentquantum theory.

Topological quantum field theoryprovided an example of background-independent quantum theory, but with no local degrees of freedom, and only finitely many degrees of freedom globally. This is inadequate to describe gravity in 3+1 dimensions, which has local degrees of freedom according to general relativity. In 2+1 dimensions, however, gravity is a topological field theory, and it has been successfully quantized in several different ways, includingspin networks.[citation needed]

Semi-classical quantum gravity[edit]

Quantum field theory on curved (non-Minkowskian) backgrounds, while not a full quantum theory of gravity, has shown many promising early results. In an analogous way to the development of quantum electrodynamics in the early part of the 20th century (when physicists considered quantum mechanics in classical electromagnetic fields), the consideration of quantum field theory on a curved background has led to predictions such as black hole radiation.

Phenomena such as theUnruh effect,in which particles exist in certain accelerating frames but not in stationary ones, do not pose any difficulty when considered on a curved background (the Unruh effect occurs even in flat Minkowskian backgrounds). The vacuum state is the state with the least energy (and may or may not contain particles).

Problem of time[edit]

A conceptual difficulty in combining quantum mechanics with general relativity arises from the contrasting role of time within these two frameworks. In quantum theories, time acts as an independent background through which states evolve, with theHamiltonian operatoracting as thegenerator of infinitesimal translationsof quantum states through time.[35]In contrast, general relativitytreats time as a dynamical variablewhich relates directly with matter and moreover requires the Hamiltonian constraint to vanish.[36]Because this variability of time has beenobserved macroscopically,it removes any possibility of employing a fixed notion of time, similar to the conception of time in quantum theory, at the macroscopic level.

Candidate theories[edit]

There are a number of proposed quantum gravity theories.[37]Currently, there is still no complete and consistent quantum theory of gravity, and the candidate models still need to overcome major formal and conceptual problems. They also face the common problem that, as yet, there is no way to put quantum gravity predictions to experimental tests, although there is hope for this to change as future data from cosmological observations and particle physics experiments become available.[38][39]

String theory[edit]

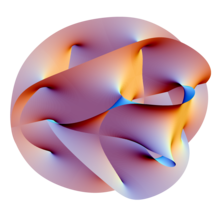

The central idea of string theory is to replace the classical concept of apoint particlein quantum field theory with a quantum theory of one-dimensional extended objects: string theory.[40]At the energies reached in current experiments, these strings are indistinguishable from point-like particles, but, crucially, differentmodesof oscillation of one and the same type of fundamental string appear as particles with different (electricand other)charges.In this way, string theory promises to be aunified descriptionof all particles and interactions.[41]The theory is successful in that one mode will always correspond to agraviton,themessenger particleof gravity; however, the price of this success is unusual features such as six extra dimensions of space in addition to the usual three for space and one for time.[42]

In what is called thesecond superstring revolution,it was conjectured that both string theory and a unification of general relativity andsupersymmetryknown assupergravity[43]form part of a hypothesized eleven-dimensional model known asM-theory,which would constitute a uniquely defined and consistent theory of quantum gravity.[44][45]As presently understood, however, string theory admits a very large number (10500by some estimates) of consistent vacua, comprising the so-called "string landscape".Sorting through this large family of solutions remains a major challenge.

Loop quantum gravity[edit]

Loop quantum gravity seriously considers general relativity's insight that spacetime is a dynamical field and is therefore a quantum object. Its second idea is that the quantum discreteness that determines the particle-like behavior of other field theories (for instance, the photons of the electromagnetic field) also affects the structure of space.

The main result of loop quantum gravity is the derivation of a granular structure of space at the Planck length. This is derived from the following considerations: In the case of electromagnetism, thequantum operatorrepresenting the energy of each frequency of the field has a discrete spectrum. Thus the energy of each frequency is quantized, and the quanta are the photons. In the case of gravity, the operators representing the area and the volume of each surface or space region likewise have discrete spectra. Thus area and volume of any portion of space are also quantized, where the quanta are elementary quanta of space. It follows, then, that spacetime has an elementary quantum granular structure at the Planck scale, which cuts off the ultraviolet infinities of quantum field theory.

The quantum state of spacetime is described in the theory by means of a mathematical structure calledspin networks.Spin networks were initially introduced byRoger Penrosein abstract form, and later shown byCarlo RovelliandLee Smolinto derive naturally from a non-perturbative quantization of general relativity. Spin networks do not represent quantum states of a field in spacetime: they represent directly quantum states of spacetime.

The theory is based on the reformulation of general relativity known asAshtekar variables,which represent geometric gravity using mathematical analogues ofelectricandmagnetic fields.[46][47]In the quantum theory, space is represented by a network structure called a spin network, evolving over time in discrete steps.[48][49][50][51]

The dynamics of the theory is today constructed in several versions. One version starts with thecanonical quantizationof general relativity. The analogue of theSchrödinger equationis aWheeler–DeWitt equation,which can be defined within the theory.[52]In the covariant, orspinfoamformulation of the theory, the quantum dynamics is obtained via a sum over discrete versions of spacetime, called spinfoams. These represent histories of spin networks.

Other theories[edit]

There are a number of other approaches to quantum gravity. The theories differ depending on which features of general relativity and quantum theory are accepted unchanged, and which features are modified.[53][54]Examples include:

- Asymptotic safety in quantum gravity

- Euclidean quantum gravity

- Integral method[55][56]

- Causal dynamical triangulation[57]

- Causal fermion systems

- Causal Set Theory

- Covariant Feynmanpath integralapproach

- Dilatonic quantum gravity

- Double copy theory

- Group field theory

- Wheeler–DeWitt equation

- Geometrodynamics

- Hořava–Lifshitz gravity

- MacDowell–Mansouri action

- Noncommutative geometry

- Path-integralbased models ofquantum cosmology[58]

- Regge calculus

- Shape Dynamics

- String-netsandquantum graphity

- Supergravity

- Twistor theory[59]

- Canonical quantum gravity

Experimental tests[edit]

As was emphasized above, quantum gravitational effects are extremely weak and therefore difficult to test. For this reason, the possibility of experimentally testing quantum gravity had not received much attention prior to the late 1990s. However, in the past decade,[clarification needed]physicists have realized that evidence for quantum gravitational effects can guide the development of the theory. Since theoretical development has been slow, the field ofphenomenological quantum gravity,which studies the possibility of experimental tests, has obtained increased attention.[60]

The most widely pursued possibilities for quantum gravity phenomenology include gravitationally mediated entanglement,[61][62]violations ofLorentz invariance,imprints of quantum gravitational effects in thecosmic microwave background(in particular its polarization), and decoherence induced by fluctuations[63][64][65]in thespace-time foam.[66]The latter scenario has been searched for in light fromgamma-ray burstsand both astrophysical and atmosphericneutrinos,placing limits on phenomenological quantum gravity parameters.[67][68][69]

ESA'sINTEGRALsatellite measured polarization of photons of different wavelengths and was able to place a limit in the granularity of space that is less than 10−48m, or 13 orders of magnitude below the Planck scale.[70][71]

TheBICEP2 experimentdetected what was initially thought to be primordialB-mode polarizationcaused bygravitational wavesin the early universe. Had the signal in fact been primordial in origin, it could have been an indication of quantum gravitational effects, but it soon transpired that the polarization was due tointerstellar dustinterference.[72]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Quantum effects in the early universe might have an observable effect on the structure of the present universe, for example, or gravity might play a role in the unification of the other forces. Cf. the text by Wald cited above.

- ^On the quantization of the geometry of spacetime, see also in the articlePlanck length,in the examples

References[edit]

- ^abRovelli, Carlo(2008)."Quantum gravity".Scholarpedia.3(5): 7117.Bibcode:2008SchpJ...3.7117R.doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.7117.

- ^Overbye, Dennis(10 October 2022)."Black Holes May Hide a Mind-Bending Secret About Our Universe - Take gravity, add quantum mechanics, stir. What do you get? Just maybe, a holographic cosmos".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 16 November 2022.Retrieved16 October2022.

- ^Kiefer, Claus (2012).Quantum gravity.International series of monographs on physics (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–4.ISBN978-0-19-958520-5.

- ^Mannheim, Philip (2006). "Alternatives to dark matter and dark energy".Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics.56(2): 340–445.arXiv:astro-ph/0505266.Bibcode:2006PrPNP..56..340M.doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2005.08.001.S2CID14024934.

- ^Nadis, Steve (2 December 2019)."Black Hole Singularities Are as Inescapable as Expected".quantamagazine.org.Quanta Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2020.Retrieved22 April2020.

- ^Bousso, Raphael (2008). "The cosmological constant".General Relativity and Gravitation.40:607–637.arXiv:0708.4231.doi:10.1007/s10714-007-0557-5.

- ^Lea, Rob (2021). "A new generation takes on the cosmological constant".Physics World.34(3): 42.doi:10.1088/2058-7058/34/03/32.

- ^Penrose, Roger (2007).The road to reality: a complete guide to the laws of the universe.Vintage. p.1017.ISBN9780679776314.OCLC716437154.

- ^Rovelli, Carlo (2001). "Notes for a brief history of quantum gravity".arXiv:gr-qc/0006061.

- ^Bose, S.; et al. (2017). "Spin Entanglement Witness for Quantum Gravity".Physical Review Letters.119(4): 240401.arXiv:1707.06050.Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119x0401B.doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.240401.PMID29286711.S2CID2684909.

- ^Marletto, C.; Vedral, V. (2017). "Gravitationally Induced Entanglement between Two Massive Particles is Sufficient Evidence of Quantum Effects in Gravity".Physical Review Letters.119(24): 240402.arXiv:1707.06036.Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119x0402M.doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.240402.PMID29286752.S2CID5163793.

- ^Nemirovsky, J.; Cohen, E.; Kaminer, I. (5 November 2021). "Spin Spacetime Censorship".Annalen der Physik.534(1).arXiv:1812.11450.doi:10.1002/andp.202100348.S2CID119342861.

- ^Hossenfelder, Sabine (2 February 2017)."What Quantum Gravity Needs Is More Experiments".Nautilus.Archived fromthe originalon 28 January 2018.Retrieved21 September2020.

- ^Experimental search for quantum gravity.Cham: Springer. 2017.ISBN9783319645360.

- ^Carney, Daniel; Stamp, Philip C. E.; Taylor, Jacob M. (7 February 2019). "Tabletop experiments for quantum gravity: a user's manual".Classical and Quantum Gravity.36(3): 034001.arXiv:1807.11494.Bibcode:2019CQGra..36c4001C.doi:10.1088/1361-6382/aaf9ca.S2CID119073215.

- ^Danielson, Daine L.; Satishchandran, Gautam; Wald, Robert M. (2022-04-05)."Gravitationally mediated entanglement: Newtonian field versus gravitons".Physical Review D.105(8): 086001.arXiv:2112.10798.Bibcode:2022PhRvD.105h6001D.doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.105.086001.S2CID245353748.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-22.Retrieved2022-12-11.

- ^Wheeler, John Archibald (2010).Geons, Black Holes, and Quantum Foam: A Life in Physics.W. W. Norton & Company.p. 235.ISBN9780393079487.

- ^Zee, Anthony(2010).Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell(second ed.).Princeton University Press.pp.172, 434–435.ISBN978-0-691-14034-6.OCLC659549695.

- ^Wald, Robert M. (1994).Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime and Black Hole Thermodynamics.University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-87027-4.

- ^Kraichnan, R. H.(1955). "Special-Relativistic Derivation of Generally Covariant Gravitation Theory".Physical Review.98(4): 1118–1122.Bibcode:1955PhRv...98.1118K.doi:10.1103/PhysRev.98.1118.

- ^Gupta, S. N.(1954). "Gravitation and Electromagnetism".Physical Review.96(6): 1683–1685.Bibcode:1954PhRv...96.1683G.doi:10.1103/PhysRev.96.1683.

- ^Gupta, S. N.(1957). "Einstein's and Other Theories of Gravitation".Reviews of Modern Physics.29(3): 334–336.Bibcode:1957RvMP...29..334G.doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.29.334.

- ^Gupta, S. N.(1962). "Quantum Theory of Gravitation".Recent Developments in General Relativity.Pergamon Press. pp. 251–258.

- ^Deser, S.(1970). "Self-Interaction and Gauge Invariance".General Relativity and Gravitation.1(1): 9–18.arXiv:gr-qc/0411023.Bibcode:1970GReGr...1....9D.doi:10.1007/BF00759198.S2CID14295121.

- ^Weinberg, Steven;Witten, Edward(1980). "Limits on massless particles".Physics Letters B.96(1–2): 59–62.Bibcode:1980PhLB...96...59W.doi:10.1016/0370-2693(80)90212-9.

- ^Horowitz, Gary T.;Polchinski, Joseph(2006). "Gauge/gravity duality". In Oriti, Daniele (ed.).Approaches to Quantum Gravity.Cambridge University Press.arXiv:gr-qc/0602037.Bibcode:2006gr.qc.....2037H.ISBN9780511575549.OCLC873715753.

- ^Rothman, Tony; Boughn, Stephen (2006)."Can Gravitons be Detected?".Foundations of Physics.36(12): 1801–1825.arXiv:gr-qc/0601043.Bibcode:2006FoPh...36.1801R.doi:10.1007/s10701-006-9081-9.S2CID14008778.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-06.Retrieved2020-05-15.

- ^Feynman, Richard P. (1995).Feynman Lectures on Gravitation.Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. pp. xxxvi–xxxviii, 211–212.ISBN978-0201627343.

- ^Hamber, H. W. (2009).Quantum Gravitation – The Feynman Path Integral Approach.Springer Nature.ISBN978-3-540-85292-6.

- ^Goroff, Marc H.; Sagnotti, Augusto; Sagnotti, Augusto (1985). "Quantum gravity at two loops".Physics Letters B.160(1–3): 81–86.Bibcode:1985PhLB..160...81G.doi:10.1016/0370-2693(85)91470-4.

- ^Distler, Jacques(2005-09-01)."Motivation".golem.ph.utexas.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-02-11.Retrieved2018-02-24.

- ^abDonoghue, John F. (1995). "Introduction to the Effective Field Theory Description of Gravity". In Cornet, Fernando (ed.).Effective Theories: Proceedings of the Advanced School, Almunecar, Spain, 26 June–1 July 1995.Singapore:World Scientific.arXiv:gr-qc/9512024.Bibcode:1995gr.qc....12024D.ISBN978-981-02-2908-5.

- ^Zinn-Justin, Jean(2007).Phase transitions and renormalization group.Oxford:Oxford University Press.ISBN9780199665167.OCLC255563633.

- ^Smolin, Lee(2001).Three Roads to Quantum Gravity.Basic Books.pp.20–25.ISBN978-0-465-07835-6.Pages 220–226 are annotated references and guide for further reading.

- ^Sakurai, J. J.; Napolitano, Jim J. (2010-07-14).Modern Quantum Mechanics(2 ed.). Pearson. p. 68.ISBN978-0-8053-8291-4.

- ^Novello, Mario; Bergliaffa, Santiago E. (2003-06-11).Cosmology and Gravitation: Xth Brazilian School of Cosmology and Gravitation; 25th Anniversary (1977–2002), Mangaratiba, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.Springer Science & Business Media. p. 95.ISBN978-0-7354-0131-0.

- ^A timeline and overview can be found inRovelli, Carlo(2000). "Notes for a brief history of quantum gravity".arXiv:gr-qc/0006061.(verify againstISBN9789812777386)

- ^Ashtekar, Abhay(2007). "Loop Quantum Gravity: Four Recent Advances and a Dozen Frequently Asked Questions".11th Marcel Grossmann Meeting on Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity.p. 126.arXiv:0705.2222.Bibcode:2008mgm..conf..126A.doi:10.1142/9789812834300_0008.ISBN978-981-283-426-3.S2CID119663169.

- ^Schwarz, John H. (2007). "String Theory: Progress and Problems".Progress of Theoretical Physics Supplement.170:214–226.arXiv:hep-th/0702219.Bibcode:2007PThPS.170..214S.doi:10.1143/PTPS.170.214.S2CID16762545.

- ^An accessible introduction at the undergraduate level can be found inZwiebach, Barton(2004).A First Course in String Theory.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-83143-7.,and more complete overviews inPolchinski, Joseph(1998).String Theory Vol. I: An Introduction to the Bosonic String.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-63303-1.andPolchinski, Joseph(1998b).String Theory Vol. II: Superstring Theory and Beyond.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-63304-8.

- ^Ibanez, L. E. (2000). "The second string (phenomenology) revolution".Classical and Quantum Gravity.17(5): 1117–1128.arXiv:hep-ph/9911499.Bibcode:2000CQGra..17.1117I.doi:10.1088/0264-9381/17/5/321.S2CID15707877.

- ^For the graviton as part of the string spectrum, e.g.Green, Schwarz & Witten 1987,sec. 2.3 and 5.3; for the extra dimensions, ibid sec. 4.2.

- ^Weinberg, Steven(2000)."Chapter 31".The Quantum Theory of Fields II: Modern Applications.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-55002-4.

- ^Townsend, Paul K. (1996). "Four Lectures on M-Theory".High Energy Physics and Cosmology.ICTP Series in Theoretical Physics.13:385.arXiv:hep-th/9612121.Bibcode:1997hepcbconf..385T.

- ^Duff, Michael(1996). "M-Theory (the Theory Formerly Known as Strings)".International Journal of Modern Physics A.11(32): 5623–5642.arXiv:hep-th/9608117.Bibcode:1996IJMPA..11.5623D.doi:10.1142/S0217751X96002583.S2CID17432791.

- ^Ashtekar, Abhay(1986). "New variables for classical and quantum gravity".Physical Review Letters.57(18): 2244–2247.Bibcode:1986PhRvL..57.2244A.doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.57.2244.PMID10033673.

- ^Ashtekar, Abhay(1987). "New Hamiltonian formulation of general relativity".Physical Review D.36(6): 1587–1602.Bibcode:1987PhRvD..36.1587A.doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.36.1587.PMID9958340.

- ^Thiemann, Thomas (2007). "Loop Quantum Gravity: An Inside View".Approaches to Fundamental Physics.Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 721. pp. 185–263.arXiv:hep-th/0608210.Bibcode:2007LNP...721..185T.doi:10.1007/978-3-540-71117-9_10.ISBN978-3-540-71115-5.S2CID119572847.

- ^Rovelli, Carlo(1998)."Loop Quantum Gravity".Living Reviews in Relativity.1(1): 1.arXiv:gr-qc/9710008.Bibcode:1998LRR.....1....1R.doi:10.12942/lrr-1998-1.PMC5567241.PMID28937180.

- ^Ashtekar, Abhay;Lewandowski, Jerzy (2004). "Background Independent Quantum Gravity: A Status Report".Classical and Quantum Gravity.21(15): R53–R152.arXiv:gr-qc/0404018.Bibcode:2004CQGra..21R..53A.doi:10.1088/0264-9381/21/15/R01.S2CID119175535.

- ^Thiemann, Thomas (2003). "Lectures on Loop Quantum Gravity".Quantum Gravity.Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 631. pp. 41–135.arXiv:gr-qc/0210094.Bibcode:2003LNP...631...41T.doi:10.1007/978-3-540-45230-0_3.ISBN978-3-540-40810-9.S2CID119151491.

- ^Rovelli, Carlo (2004).Quantum Gravity.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-71596-6.

- ^Isham, Christopher J.(1994). "Prima facie questions in quantum gravity". In Ehlers, Jürgen; Friedrich, Helmut (eds.).Canonical Gravity: From Classical to Quantum.Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 434. Springer. pp. 1–21.arXiv:gr-qc/9310031.Bibcode:1994LNP...434....1I.doi:10.1007/3-540-58339-4_13.ISBN978-3-540-58339-4.S2CID119364176.

- ^Sorkin, Rafael D.(1997). "Forks in the Road, on the Way to Quantum Gravity".International Journal of Theoretical Physics.36(12): 2759–2781.arXiv:gr-qc/9706002.Bibcode:1997IJTP...36.2759S.doi:10.1007/BF02435709.S2CID4803804.

- ^Klimets, A. P. (2017)."Philosophy Documentation Center, Western University – Canada"(PDF).Philosophy Documentation Center, Western University – Canada. pp. 25–32.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2019-07-01.Retrieved2020-04-24.

- ^A.P. Klimets. (2023). Quantum Gravity. Current Research in Statistics & Mathematics, 2(1), 141-155.

- ^Loll, Renate (1998)."Discrete Approaches to Quantum Gravity in Four Dimensions".Living Reviews in Relativity.1(1): 13.arXiv:gr-qc/9805049.Bibcode:1998LRR.....1...13L.doi:10.12942/lrr-1998-13.PMC5253799.PMID28191826.

- ^Hawking, Stephen W.(1987). "Quantum cosmology". In Hawking, Stephen W.; Israel, Werner (eds.).300 Years of Gravitation.Cambridge University Press. pp. 631–651.ISBN978-0-521-37976-2.

- ^See ch. 33 inPenrose 2004and references therein.

- ^Hossenfelder, Sabine (2011)."Experimental Search for Quantum Gravity".In Frignanni, V. R. (ed.).Classical and Quantum Gravity: Theory, Analysis and Applications.Nova Publishers.ISBN978-1-61122-957-8.Archived fromthe originalon 2017-07-01.Retrieved2012-04-01.

- ^Bose, Sougato; Mazumdar, Anupam; Morley, Gavin W.; Ulbricht, Hendrik; Toroš, Marko; Paternostro, Mauro; Geraci, Andrew A.; Barker, Peter F.; Kim, M. S.; Milburn, Gerard (2017-12-13)."Spin Entanglement Witness for Quantum Gravity".Physical Review Letters.119(24): 240401.arXiv:1707.06050.Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119x0401B.doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.240401.PMID29286711.S2CID2684909.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-22.Retrieved2022-07-13.

- ^Marletto, C.; Vedral, V. (2017-12-13)."Gravitationally Induced Entanglement between Two Massive Particles is Sufficient Evidence of Quantum Effects in Gravity".Physical Review Letters.119(24): 240402.arXiv:1707.06036.Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119x0402M.doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.240402.PMID29286752.S2CID5163793.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-22.Retrieved2022-07-13.

- ^Oniga, Teodora; Wang, Charles H.-T. (2016-02-09)."Quantum gravitational decoherence of light and matter".Physical Review D.93(4): 044027.arXiv:1511.06678.Bibcode:2016PhRvD..93d4027O.doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.93.044027.hdl:2164/5830.S2CID119210226.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-22.Retrieved2021-01-01.

- ^Oniga, Teodora; Wang, Charles H.-T. (2017-10-05)."Quantum coherence, radiance, and resistance of gravitational systems".Physical Review D.96(8): 084014.arXiv:1701.04122.Bibcode:2017PhRvD..96h4014O.doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.96.084014.hdl:2164/9320.S2CID54777871.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-22.Retrieved2021-01-01.

- ^Quiñones, D. A.; Oniga, T.; Varcoe, B. T. H.; Wang, C. H.-T. (2017-08-15)."Quantum principle of sensing gravitational waves: From the zero-point fluctuations to the cosmological stochastic background of spacetime".Physical Review D.96(4): 044018.arXiv:1702.03905.Bibcode:2017PhRvD..96d4018Q.doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.96.044018.hdl:2164/9150.S2CID55056264.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-22.Retrieved2021-01-02.

- ^Oniga, Teodora; Wang, Charles H.-T. (2016-09-19)."Spacetime foam induced collective bundling of intense fields".Physical Review D.94(6): 061501.arXiv:1603.09193.Bibcode:2016PhRvD..94f1501O.doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.94.061501.hdl:2164/7434.S2CID54872718.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-22.Retrieved2021-01-02.

- ^Vasileiou, Vlasios; Granot, Jonathan; Piran, Tsvi; Amelino-Camelia, Giovanni (2015-03-16)."A Planck-scale limit on spacetime fuzziness and stochastic Lorentz invariance violation".Nature Physics.11(4): 344–346.Bibcode:2015NatPh..11..344V.doi:10.1038/nphys3270.ISSN1745-2473.S2CID54727053.

- ^The IceCube Collaboration; Abbasi, R.; Ackermann, M.; Adams, J.; Aguilar, J. A.; Ahlers, M.; Ahrens, M.; Alameddine, J. M.; Alispach, C.; Alves Jr, A. A.; Amin, N. M.; Andeen, K.; Anderson, T.; Anton, G.; Argüelles, C. (2022-11-01)."Search for quantum gravity using astrophysical neutrino flavour with IceCube".Nature Physics.18(11): 1287–1292.arXiv:2111.04654.Bibcode:2022NatPh..18.1287I.doi:10.1038/s41567-022-01762-1.ISSN1745-2473.S2CID243848123.

- ^Abbasi, R. and others, IceCube Collaboration (June 2023). "Searching for Decoherence from Quantum Gravity at the IceCube South Pole Neutrino Observatory".arXiv:hep-ex/2308.00105.

- ^"Integral challenges physics beyond Einstein".European Space Agency.2011-06-30.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-11-13.Retrieved2021-11-06.

- ^Laurent, P.; Götz, D.; Binétruy, P.; Covino, S.; Fernandez-Soto, A. (2011-06-28)."Constraints on Lorentz Invariance Violation using integral/IBIS observations of GRB041219A".Physical Review D.83(12): 121301.arXiv:1106.1068.Bibcode:2011PhRvD..83l1301L.doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.83.121301.ISSN1550-7998.S2CID53603505.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-22.Retrieved2021-11-06.

- ^ Cowen, Ron (30 January 2015). "Gravitational waves discovery now officially dead".Nature.doi:10.1038/nature.2015.16830.S2CID124938210.

Sources[edit]

- Green, M.B.;Schwarz, J.H.;Witten, E.(1987).Superstring theory.Vol. l.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9781107029118.

- Penrose, Roger(2004),The Road to Reality,A. A. Knopf,ISBN978-0-679-45443-4

Further reading[edit]

- Ahluwalia, D. V. (2002). "Interface of Gravitational and Quantum Realms".Modern Physics Letters A.17(15–17): 1135–1145.arXiv:gr-qc/0205121.Bibcode:2002MPLA...17.1135A.doi:10.1142/S021773230200765X.S2CID119358167.

- Ashtekar, Abhay(2005)."The winding road to quantum gravity"(PDF).Current Science.89:2064–2074.JSTOR24111069.

- Carlip, Steven(2001). "Quantum Gravity: a Progress Report".Reports on Progress in Physics.64(8): 885–942.arXiv:gr-qc/0108040.Bibcode:2001RPPh...64..885C.doi:10.1088/0034-4885/64/8/301.S2CID118923209.

- Hamber, Herbert W. (2009). Hamber, Herbert W. (ed.).Quantum Gravitation.Springer Nature.doi:10.1007/978-3-540-85293-3.hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-471D-A.ISBN978-3-540-85292-6.

- Kiefer, Claus (2007).Quantum Gravity.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-921252-1.

- Kiefer, Claus (2005). "Quantum Gravity: General Introduction and Recent Developments".Annalen der Physik.15(1): 129–148.arXiv:gr-qc/0508120.Bibcode:2006AnP...518..129K.doi:10.1002/andp.200510175.S2CID12984346.

- Lämmerzahl, Claus, ed. (2003).Quantum Gravity: From Theory to Experimental Search.Lecture Notes in Physics.Springer.ISBN978-3-540-40810-9.

- Rovelli, Carlo(2004).Quantum Gravity.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-83733-0.

External links[edit]

- Weinstein, Steven; Rickles, Dean."Quantum Gravity".InZalta, Edward N.(ed.).Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Planck Era" and "Planck Time"Archived2018-11-28 at theWayback Machine(up to 10−43seconds afterbirthofUniverse) (University of Oregon).

- "Quantum Gravity",BBC Radio 4 discussion with John Gribbin, Lee Smolin and Janna Levin (In Our Time,February 22, 2001)