Quasar

Aquasar(/ˈkweɪzɑːr/KWAY-zar) is an extremelyluminousactive galactic nucleus(AGN). It is sometimes known as aquasi-stellar object,abbreviatedQSO.The emission from an AGN is powered by asupermassive black holewith a mass ranging from millions to tens of billions ofsolar masses,surrounded by a gaseousaccretion disc.Gas in the disc falling towards the black hole heats up and releasesenergyin the form ofelectromagnetic radiation.Theradiant energyof quasars is enormous; the most powerful quasars haveluminositiesthousands of times greater than that of agalaxysuch as theMilky Way.[2][3]Quasars are usually categorized as a subclass of the more general category of AGN. Theredshiftsof quasars are ofcosmological origin.[4]

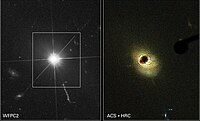

The termquasaroriginated as acontractionof "quasi-stellar[star-like]radio source "—because they were first identified during the 1950s as sources of radio-wave emission of unknown physical origin—and when identified in photographic images at visible wavelengths, they resembled faint, star-like points of light. High-resolution images of quasars, particularly from theHubble Space Telescope,have shown that quasars occur in thecenters of galaxies,and that some host galaxies are stronglyinteractingormerginggalaxies.[5]As with other categories of AGN, the observed properties of a quasar depend on many factors, including the mass of the black hole, the rate of gas accretion, the orientation of the accretion disc relative to the observer, the presence or absence of ajet,and the degree ofobscurationby gas anddustwithin the host galaxy.

About a million quasars have been identified with reliablespectroscopicredshifts,[6]and between 2-3 million identified inphotometriccatalogs.[7][8]Thenearest knownquasar is about 600 millionlight-yearsfrom Earth. The record for the most distant known quasar continues to change. In 2017, quasarULAS J1342+0928was detected atredshiftz= 7.54. Light observed from this 800-million-solar-massquasar was emitted when the universe was only 690 million years old.[9][10][11]In 2020, quasarPōniuāʻenawas detected from a time only 700 million years after theBig Bang,and with an estimated mass of 1.5 billion times the mass of the Sun.[12][13]In early 2021, the quasarQSO J0313–1806,with a 1.6-billion-solar-mass black hole, was reported atz= 7.64, 670 million years after the Big Bang.[14]

Quasar discovery surveys have shown that quasar activity was more common in the distant past; the peak epoch was approximately 10 billion years ago.[15]Concentrations of multiple quasars are known aslarge quasar groupsand may constitute some of thelargest known structuresin the universe if the observed groups are good tracers of mass distribution.

Naming[edit]

The termquasarwas first used in an article byastrophysicistHong-Yee Chiuin May 1964, inPhysics Today,to describe certain astronomically puzzling objects:[16]

So far, the clumsily long name "quasi-stellar radio sources" is used to describe these objects. Because the nature of these objects is entirely unknown, it is hard to prepare a short, appropriate nomenclature for them so that their essential properties are obvious from their name. For convenience, the abbreviated form "quasar" will be used throughout this paper.

History of observation and interpretation[edit]

Background[edit]

Between 1917 and 1922, it became clear from work byHeber Doust Curtis,Ernst Öpikand others that some objects ( "nebulae") seen by astronomers were in fact distantgalaxieslike the Milky Way. But whenradio astronomybegan in the 1950s, astronomers detected, among the galaxies, a small number of anomalous objects with properties that defied explanation.

The objects emitted large amounts of radiation of many frequencies, but no source could be located optically, or in some cases only a faint andpoint-likeobject somewhat like a distantstar.Thespectral linesof these objects, which identify thechemical elementsof which the object is composed, were also extremely strange and defied explanation. Some of them changed theirluminosityvery rapidly in the optical range and even more rapidly in the X-ray range, suggesting an upper limit on their size, perhaps no larger than theSolar System.[17]This implies an extremely highpower density.[18]Considerable discussion took place over what these objects might be. They were described as"quasi-stellar[meaning: star-like]radio sources ",or"quasi-stellar objects"(QSOs), a name which reflected their unknown nature, and this became shortened to "quasar".

Early observations (1960s and earlier)[edit]

The first quasars (3C 48and3C 273) were discovered in the late 1950s, as radio sources in all-sky radio surveys.[19][20][21][22]They were first noted as radio sources with no corresponding visible object. Using small telescopes and theLovell Telescopeas aninterferometer,they were shown to have a very small angular size.[23]By 1960, hundreds of these objects had been recorded and published in theThird Cambridge Cataloguewhile astronomers scanned the skies for their optical counterparts. In 1963, a definite identification of the radio source3C 48with an optical object was published byAllan SandageandThomas A. Matthews.Astronomers had detected what appeared to be a faint blue star at the location of the radio source and obtained its spectrum, which contained many unknown broad emission lines. The anomalous spectrum defied interpretation.

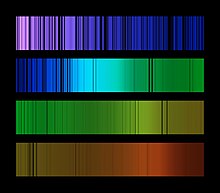

British-Australian astronomerJohn Boltonmade many early observations of quasars, including a breakthrough in 1962. Another radio source,3C 273,was predicted to undergo fiveoccultationsby theMoon.Measurements taken byCyril Hazardand John Bolton during one of the occultations using theParkes Radio TelescopeallowedMaarten Schmidtto find a visible counterpart to the radio source and obtain anoptical spectrumusing the 200-inch (5.1 m)Hale TelescopeonMount Palomar.This spectrum revealed the same strange emission lines. Schmidt was able to demonstrate that these were likely to be the ordinaryspectral linesof hydrogen redshifted by 15.8%, at the time, a high redshift (with only a handful of much fainter galaxies known with higher redshift). If this was due to the physical motion of the "star", then 3C 273 was receding at an enormous velocity, around47000km/s,far beyond the speed of any known star and defying any obvious explanation.[24]Nor would an extreme velocity help to explain 3C 273's huge radio emissions. If the redshift was cosmological (now known to be correct), the large distance implied that 3C 273 was far more luminous than any galaxy, but much more compact. Also, 3C 273 was bright enough to detect on archival photographs dating back to the 1900s; it was found to be variable on yearly timescales, implying that a substantial fraction of the light was emitted from a region less than 1 light-year in size, tiny compared to a galaxy.

Although it raised many questions, Schmidt's discovery quickly revolutionized quasar observation. The strange spectrum of3C 48was quickly identified by Schmidt, Greenstein and Oke ashydrogenandmagnesiumredshifted by 37%. Shortly afterwards, two more quasar spectra in 1964 and five more in 1965 were also confirmed as ordinary light that had been redshifted to an extreme degree.[25]While the observations and redshifts themselves were not doubted, their correct interpretation was heavily debated, and Bolton's suggestion that the radiation detected from quasars were ordinaryspectral linesfrom distant highly redshifted sources with extreme velocity was not widely accepted at the time.

Development of physical understanding (1960s)[edit]

An extreme redshift could imply great distance and velocity but could also be due to extreme mass or perhaps some other unknown laws of nature. Extreme velocity and distance would also imply immense power output, which lacked explanation. The small sizes were confirmed byinterferometryand by observing the speed with which the quasar as a whole varied in output, and by their inability to be seen in even the most powerful visible-light telescopes as anything more than faint starlike points of light. But if they were small and far away in space, their power output would have to be immense and difficult to explain. Equally, if they were very small and much closer to this galaxy, it would be easy to explain their apparent power output, but less easy to explain their redshifts and lack of detectable movement against the background of the universe.

Schmidt noted that redshift is also associated with the expansion of the universe, as codified inHubble's law.If the measured redshift was due to expansion, then this would support an interpretation of very distant objects with extraordinarily highluminosityand power output, far beyond any object seen to date. This extreme luminosity would also explain the large radio signal. Schmidt concluded that 3C 273 could either be an individual star around 10 km wide within (or near to) this galaxy, or a distant active galactic nucleus. He stated that a distant and extremely powerful object seemed more likely to be correct.[26]

Schmidt's explanation for the high redshift was not widely accepted at the time. A major concern was the enormous amount of energy these objects would have to be radiating, if they were distant. In the 1960s no commonly accepted mechanism could account for this. The currently accepted explanation, that it is due tomatterin anaccretion discfalling into asupermassive black hole,was only suggested in 1964 byEdwin E. SalpeterandYakov Zeldovich,[27]and even then it was rejected by many astronomers, as at this time the existence ofblack holesat all was widely seen as theoretical.

Various explanations were proposed during the 1960s and 1970s, each with their own problems. It was suggested that quasars were nearby objects, and that their redshift was not due to theexpansion of spacebut rather tolight escaping a deep gravitational well.This would require a massive object, which would also explain the high luminosities. However, a star of sufficient mass to produce the measured redshift would be unstable and in excess of theHayashi limit.[28]Quasars also showforbiddenspectral emission lines, previously only seen in hot gaseous nebulae of low density, which would be too diffuse to both generate the observed power and fit within a deep gravitational well.[29]There were also serious concerns regarding the idea of cosmologically distant quasars. One strong argument against them was that they implied energies that were far in excess of known energy conversion processes, includingnuclear fusion.There were suggestions that quasars were made of some hitherto unknown stable form ofantimatterin similarly unknown types of region of space, and that this might account for their brightness.[30]Others speculated that quasars were awhite holeend of awormhole,[31][32]or achain reactionof numeroussupernovae.[33]

Eventually, starting from about the 1970s, many lines of evidence (includingthe firstX-rayspace observatories,knowledge ofblack holesand modern models ofcosmology) gradually demonstrated that the quasar redshifts are genuine and due to theexpansion of space,that quasars are in fact as powerful and as distant as Schmidt and some other astronomers had suggested, and that their energy source is matter from an accretion disc falling onto a supermassive black hole.[34]This included crucial evidence from optical and X-ray viewing of quasar host galaxies, finding of "intervening" absorption lines, which explained various spectral anomalies, observations fromgravitational lensing,Gunn's 1971 finding that galaxies containing quasars showed the same redshift as the quasars,[35]andKristian's 1973 finding that the "fuzzy" surrounding of many quasars was consistent with a less luminous host galaxy.[36]

This model also fits well with other observations suggesting that many or even most galaxies have a massive central black hole. It would also explain why quasars are more common in the early universe: as a quasar draws matter from its accretion disc, there comes a point when there is less matter nearby, and energy production falls off or ceases, as the quasar becomes a more ordinary type of galaxy.

The accretion-disc energy-production mechanism was finally modeled in the 1970s, and black holes were also directly detected (including evidence showing that supermassive black holes could be found at the centers of this and many other galaxies), which resolved the concern that quasars were too luminous to be a result of very distant objects or that a suitable mechanism could not be confirmed to exist in nature. By 1987 it was "well accepted" that this was the correct explanation for quasars,[37]and the cosmological distance and energy output of quasars was accepted by almost all researchers.

Modern observations (1970s and onward)[edit]

Later it was found that not all quasars have strong radio emission; in fact only about 10% are "radio-loud". Hence the name "QSO" (quasi-stellar object) is used (in addition to "quasar" ) to refer to these objects, further categorized into the "radio-loud" and the "radio-quiet" classes. The discovery of the quasar had large implications for the field of astronomy in the 1960s, including drawing physics and astronomy closer together.[39]

In 1979, thegravitational lenseffect predicted byAlbert Einstein'sgeneral theory of relativitywas confirmed observationally for the first time with images of thedouble quasar0957+561.[40]

A study published in February 2021 showed that there are more quasars in one direction (towardsHydra) than in the opposite direction, seemingly indicating that the Earth is moving in that direction. But the direction of this dipole is about 28° away from the direction of the Earth's motion relative to thecosmic microwave backgroundradiation.[41]

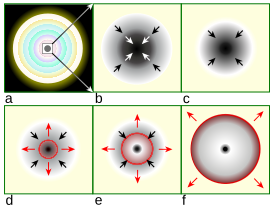

In March 2021, a collaboration of scientists, related to theEvent Horizon Telescope,presented, for the first time, apolarized-based imageof ablack hole,specifically the black hole at the center ofMessier 87,anelliptical galaxyapproximately 55 million light-years away in theconstellationVirgo,revealing the forces giving rise to quasars.[42]

Current understanding[edit]

−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is now known that quasars are distant but extremely luminous objects, so any light that reaches theEarthis redshifted due to theexpansion of the universe.[43]

Quasars inhabit the centers of active galaxies and are among the most luminous, powerful, and energetic objects known in the universe, emitting up to a thousand times the energy output of theMilky Way,which contains 200–400 billion stars. This radiation is emitted across the electromagnetic spectrum almost uniformly, from X-rays to the far infrared with a peak in the ultraviolet optical bands, with some quasars also being strong sources of radio emission and of gamma-rays. With high-resolution imaging from ground-based telescopes and theHubble Space Telescope,the "host galaxies" surrounding the quasars have been detected in some cases.[44]These galaxies are normally too dim to be seen against the glare of the quasar, except with special techniques. Most quasars, with the exception of3C 273,whose averageapparent magnitudeis 12.9, cannot be seen with small telescopes.

Quasars are believed—and in many cases confirmed—to be powered byaccretionof material into supermassive black holes in the nuclei of distant galaxies, as suggested in 1964 byEdwin SalpeterandYakov Zeldovich.[19]Light and other radiation cannot escape from within theevent horizonof a black hole. The energy produced by a quasar is generatedoutsidethe black hole, by gravitational stresses and immensefrictionwithin the material nearest to the black hole, as it orbits and falls inward.[37]The huge luminosity of quasars results from the accretion discs of central supermassive black holes, which can convert between 5.7% and 32% of themassof an object intoenergy,[45]compared to just 0.7% for thep–p chainnuclear fusionprocess that dominates the energy production in Sun-like stars. Central masses of 105to 109solar masseshave been measured in quasars by usingreverberation mapping.Several dozen nearby large galaxies, including theMilky Waygalaxy, that do not have an active center and do not show any activity similar to a quasar, are confirmed to contain a similar supermassive black hole in theirnuclei (galactic center).Thus it is now thought that all large galaxies have a black hole of this kind, but only a small fraction have sufficient matter in the right kind of orbit at their center to become active and power radiation in such a way as to be seen as quasars.[46]

This also explains why quasars were more common in the early universe, as this energy production ends when the supermassive black hole consumes all of the gas and dust near it. This means that it is possible that most galaxies, including the Milky Way, have gone through an active stage, appearing as a quasar or some other class of active galaxy that depended on the black-hole mass and the accretion rate, and are now quiescent because they lack a supply of matter to feed into their central black holes to generate radiation.[46]

The matter accreting onto the black hole is unlikely to fall directly in, but will have some angular momentum around the black hole, which will cause the matter to collect into anaccretion disc.Quasars may also be ignited or re-ignited when normal galaxies merge and the black hole is infused with a fresh source of matter.[48]In fact, it has been suggested that a quasar could form when theAndromeda Galaxycollides with theMilky Waygalaxy in approximately 3–5 billion years.[37][49][50][51]

In the 1980s, unified models were developed in which quasars were classified as a particular kind ofactive galaxy,and a consensus emerged that in many cases it is simply the viewing angle that distinguishes them from other active galaxies, such asblazarsandradio galaxies.[52]

The highest-redshift quasar known (as of December 2017[update]) wasULAS J1342+0928,with a redshift of 7.54,[53]which corresponds to acomoving distanceof approximately 29.36 billionlight-yearsfrom Earth (these distances are much larger than the distance light could travel in the universe's 13.8-billion-year history because the universe is expanding).

It is now understood that many quasars are triggered by the collisions of galaxies, which drives the mass of the galaxies into the supermassive black holes at their centers.

Properties[edit]

More than900,000quasars have been found (as of July 2023),[6]most from theSloan Digital Sky Survey.All observed quasar spectra have redshifts between 0.056 and 7.64 (as of 2021), which means they range between 600 million and 30 billionlight-years away from Earth.Because of the great distances to the farthest quasars and the finite velocity of light, they and their surrounding space appear as they existed in the very early universe.

The power of quasars originates from supermassive black holes that are believed to exist at the core of most galaxies. The Doppler shifts of stars near the cores of galaxies indicate that they are revolving around tremendous masses with very steep gravity gradients, suggesting black holes.

Although quasars appear faint when viewed from Earth, they are visible from extreme distances, being the most luminous objects in the known universe. The brightest quasar in the sky is3C 273in theconstellationofVirgo.It has an averageapparent magnitudeof 12.8 (bright enough to be seen through a medium-size amateurtelescope), but it has anabsolute magnitudeof −26.7.[55]From a distance of about 33 light-years, this object would shine in the sky about as brightly as theSun.This quasar'sluminosityis, therefore, about 4 trillion (4×1012) times that of the Sun, or about 100 times that of the total light of giant galaxies like theMilky Way.[55]This assumes that the quasar is radiating energy in all directions, but the active galactic nucleus is believed to be radiating preferentially in the direction of its jet. In a universe containing hundreds of billions of galaxies, most of which had active nuclei billions of years ago but only seen today, it is statistically certain that thousands of energy jets should be pointed toward the Earth, some more directly than others. In many cases it is likely that the brighter the quasar, the more directly its jet is aimed at the Earth. Such quasars are calledblazars.

The hyperluminous quasarAPM 08279+5255was, when discovered in 1998, given anabsolute magnitudeof −32.2. High-resolution imaging with theHubble Space Telescopeand the 10 mKeck Telescoperevealed that this system isgravitationally lensed.A study of the gravitational lensing of this system suggests that the light emitted has been magnified by a factor of ~10. It is still substantially more luminous than nearby quasars such as 3C 273.

Quasars were much more common in the early universe than they are today. This discovery byMaarten Schmidtin 1967 was early strong evidence againststeady-state cosmologyand in favor of theBig Bangcosmology. Quasars show the locations where supermassive black holes are growing rapidly (byaccretion). Detailed simulations reported in 2021 showed that galaxy structures, such as spiral arms, use gravitational forces to 'put the brakes on' gas that would otherwise orbit galaxy centers forever; instead the braking mechanism enabled the gas to fall into the supermassive black holes, releasing enormous radiant energies.[56][57]These black holes co-evolve with the mass of stars in their host galaxy in a way not fully understood at present. One idea is that jets, radiation and winds created by the quasars shut down the formation of new stars in the host galaxy, a process called "feedback". The jets that produce strong radio emission in some quasars at the centers ofclusters of galaxiesare known to have enough power to prevent the hot gas in those clusters from cooling and falling on to the central galaxy.

Quasars' luminosities are variable, with time scales that range from months to hours. This means that quasars generate and emit their energy from a very small region, since each part of the quasar would have to be in contact with other parts on such a time scale as to allow the coordination of the luminosity variations. This would mean that a quasar varying on a time scale of a few weeks cannot be larger than a few light-weeks across. The emission of large amounts of power from a small region requires a power source far more efficient than the nuclear fusion that powers stars. The conversion ofgravitational potential energyto radiation by infalling to a black hole converts between 6% and 32% of the mass to energy, compared to 0.7% for the conversion of mass to energy in a star like the Sun.[45]It is the only process known that can produce such high power over a very long term. (Stellar explosions such assupernovasandgamma-ray bursts,and directmatter–antimatterannihilation, can also produce very high power output, but supernovae only last for days, and the universe does not appear to have had large amounts of antimatter at the relevant times.)

Since quasars exhibit all the properties common to otheractive galaxiessuch asSeyfert galaxies,the emission from quasars can be readily compared to those of smaller active galaxies powered by smaller supermassive black holes. To create a luminosity of 1040watts(the typical brightness of a quasar), a supermassive black hole would have to consume the material equivalent of 10 solar masses per year. The brightest known quasars devour 1000 solar masses of material every year. The largest known is estimated to consume matter equivalent to 10 Earths per second. Quasar luminosities can vary considerably over time, depending on their surroundings. Since it is difficult to fuel quasars for many billions of years, after a quasar finishes accreting the surrounding gas and dust, it becomes an ordinary galaxy.

Radiation from quasars is partially "nonthermal" (i.e., not due toblack-body radiation), and approximately 10% are observed to also have jets and lobes like those ofradio galaxiesthat also carry significant (but poorly understood) amounts of energy in the form of particles moving atrelativistic speeds.Extremely high energies might be explained by several mechanisms (seeFermi accelerationandCentrifugal mechanism of acceleration). Quasars can be detected over the entire observableelectromagnetic spectrum,includingradio,infrared,visible light,ultraviolet,X-rayand evengamma rays.Most quasars are brightest in their rest-frame ultravioletwavelengthof 121.6nmLyman- Alphaemission line of hydrogen, but due to the tremendous redshifts of these sources, that peak luminosity has been observed as far to the red as 900.0 nm, in the near infrared. A minority of quasars show strong radio emission, which is generated by jets of matter moving close to the speed of light. When viewed downward, these appear asblazarsand often have regions that seem to move away from the center faster than the speed of light (superluminalexpansion). This is an optical illusion due to the properties ofspecial relativity.

Quasar redshifts are measured from the strongspectral linesthat dominate their visible and ultraviolet emission spectra. These lines are brighter than the continuous spectrum. They exhibitDoppler broadeningcorresponding to mean speed of several percent of the speed of light. Fast motions strongly indicate a large mass. Emission lines of hydrogen (mainly of theLyman seriesandBalmer series), helium, carbon, magnesium, iron and oxygen are the brightest lines. The atoms emitting these lines range from neutral to highly ionized, leaving it highly charged. This wide range of ionization shows that the gas is highly irradiated by the quasar, not merely hot, and not by stars, which cannot produce such a wide range of ionization.

Like all (unobscured) active galaxies, quasars can be strong X-ray sources. Radio-loud quasars can also produce X-rays and gamma rays byinverse Compton scatteringof lower-energy photons by the radio-emitting electrons in the jet.[59]

Iron quasarsshow strong emission lines resulting from low-ionizationiron(FeII), such as IRAS 18508-7815.

Spectral lines, reionization, and the early universe[edit]

Quasars also provide some clues as to the end of theBig Bang'sreionization.The oldest known quasars (z= 6)[needs update]display aGunn–Peterson troughand have absorption regions in front of them indicating that theintergalactic mediumat that time wasneutral gas.More recent quasars show no absorption region, but rather their spectra contain a spiky area known as theLyman- Alpha forest;this indicates that the intergalactic medium has undergone reionization intoplasma,and that neutral gas exists only in small clouds.

The intense production ofionizingultravioletradiation is also significant, as it would provide a mechanism for reionization to occur as galaxies form. Despite this, current theories suggest that quasars were not the primary source of reionization; the primary causes of reionization were probably the earliest generations ofstars,known asPopulation IIIstars (possibly 70%), anddwarf galaxies(very early small high-energy galaxies) (possibly 30%).[60][61][62][63][64][65]

Quasars show evidence of elements heavier thanhelium,indicating that galaxies underwent a massive phase ofstar formation,creatingpopulation III starsbetween the time of theBig Bangand the first observed quasars. Light from these stars may have been observed in 2005 usingNASA'sSpitzer Space Telescope,[66]although this observation remains to be confirmed.

Quasar subtypes[edit]

Thetaxonomyof quasars includes various subtypes representing subsets of the quasar population having distinct properties.

- Radio-loud quasarsare quasars with powerfuljetsthat are strong sources of radio-wavelength emission. These make up about 10% of the overall quasar population.[67]

- Radio-quiet quasarsare those quasars lacking powerful jets, with relatively weaker radio emission than the radio-loud population. The majority of quasars (about 90%) are radio-quiet.[67]

- Broad absorption-line (BAL) quasarsare quasars whose spectra exhibit broad absorption lines that are blue-shifted relative to the quasar's rest frame, resulting from gas flowing outward from the active nucleus in the direction toward the observer. Broad absorption lines are found in about 10% of quasars, and BAL quasars are usually radio-quiet.[67]In the rest-frame ultraviolet spectra of BAL quasars, broad absorption lines can be detected from ionized carbon, magnesium, silicon, nitrogen, and other elements.

- Type 2 (or Type II) quasarsare quasars in which the accretion disc and broad emission lines are highly obscured by dense gas anddust.They are higher-luminosity counterparts of Type 2 Seyfert galaxies.[68]

- Red quasarsare quasars with optical colors that are redder than normal quasars, thought to be the result of moderate levels of dustextinctionwithin the quasar host galaxy. Infrared surveys have demonstrated that red quasars make up a substantial fraction of the total quasar population.[69]

- Optically violent variable(OVV) quasarsare radio-loud quasars in which the jet is directed toward the observer. Relativistic beaming of the jet emission results in strong and rapid variability of the quasar brightness. OVV quasars are also considered to be a type ofblazar.

- Weak emission line quasarsare quasars having unusually faint emission lines in the ultraviolet/visible spectrum.[70]

Role in celestial reference systems[edit]

Because quasars are extremely distant, bright, and small in apparent size, they are useful reference points in establishing a measurement grid on the sky.[72] TheInternational Celestial Reference System(ICRS) is based on hundreds of extra-galactic radio sources, mostly quasars, distributed around the entire sky. Because they are so distant, they are apparently stationary to current technology, yet their positions can be measured with the utmost accuracy byvery-long-baseline interferometry(VLBI). The positions of most are known to 0.001arcsecondor better, which is orders of magnitude more precise than the best optical measurements.

Multiple quasars[edit]

A grouping of two or more quasars on the sky can result from a chance alignment, where the quasars are not physically associated, from actual physical proximity, or from the effects of gravity bending the light of a single quasar into two or more images bygravitational lensing.

When two quasars appear to be very close to each other as seen from Earth (separated by a fewarcsecondsor less), they are commonly referred to as a "double quasar". When the two are also close together in space (i.e. observed to have similar redshifts), they are termed a "quasar pair", or as a "binary quasar" if they are close enough that their host galaxies are likely to be physically interacting.[73]

As quasars are overall rare objects in the universe, the probability of three or more separate quasars being found near the same physical location is very low, and determining whether the system is closely separated physically requires significant observational effort. The first true triple quasar was found in 2007 by observations at theW. M. Keck ObservatoryinMauna Kea,Hawaii.[74]LBQS 1429-008(or QQQ J1432-0106) was first observed in 1989 and at the time was found to be a double quasar. Whenastronomersdiscovered the third member, they confirmed that the sources were separate and not the result of gravitational lensing. This triple quasar has a redshift ofz= 2.076.[75]The components are separated by an estimated 30–50kiloparsecs(roughly 97,000–160,000 light-years), which is typical for interacting galaxies.[76]In 2013, the second true triplet of quasars, QQQ J1519+0627, was found with a redshiftz= 1.51, the whole system fitting within a physical separation of 25 kpc (about 80,000 light-years).[77][78]

The first true quadruple quasar system was discovered in 2015 at a redshiftz= 2.0412 and has an overall physical scale of about 200 kpc (roughly 650,000 light-years).[79]

A multiple-image quasar is a quasar whose light undergoesgravitational lensing,resulting in double, triple or quadruple images of the same quasar. The first such gravitational lens to be discovered was the double-imaged quasarQ0957+561(or Twin Quasar) in 1979.[80] An example of a triply lensed quasar is PG1115+08.[81] Several quadruple-image quasars are known, including theEinstein Crossand theCloverleaf Quasar,with the first such discoveries happening in the mid-1980s.

Gallery[edit]

-

These two NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope images reveal two pairs of quasars that existed 10 billion years ago and reside at the hearts of merging galaxies.[82]

-

This image from the NASA/ESA/CSAJames Webb Space Telescopeshows an arrangement of ten galaxies. The 3 million light-year-long filament is anchored by a quasar.

-

The quasar SDSS J165202.64+172852.3 images in the center and on the right present new observations from the JWST in multiple wavelengths to demonstrate the distribution of gas around the object.[83]

See also[edit]

- Galaxy formation and evolution

- Large quasar group

- List of quasars

- List of microquasars

- Microquasar

- Quasi-star

References[edit]

- ^"Most Distant Quasar Found".ESO Science Release.Retrieved4 July2011.

- ^Wu, Xue-Bing; et al. (2015). "An ultraluminous quasar with a twelve-billion-solar-mass black hole at redshift 6.30".Nature.518(7540): 512–515.arXiv:1502.07418.Bibcode:2015Natur.518..512W.doi:10.1038/nature14241.PMID25719667.S2CID4455954.

- ^Frank, Juhan; King, Andrew; Raine, Derek J. (February 2002).Accretion Power in Astrophysics(Third ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.Bibcode:2002apa..book.....F.ISBN0521620538.

- ^"Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei".ned.ipac.caltech.edu.Retrieved2020-08-31.

- ^Bahcall, J. N.; et al. (1997). "Hubble Space Telescope Images of a Sample of 20 Nearby Luminous Quasars".The Astrophysical Journal.479(2): 642–658.arXiv:astro-ph/9611163.Bibcode:1997ApJ...479..642B.doi:10.1086/303926.S2CID15318893.

- ^ab"Million Quasars Catalog, Version 8 (2 August 2023)".MILLIQUAS.2023-08-02.Retrieved2023-11-20.

- ^Shu, Yiping; Koposov, Sergey E; Evans, N Wyn; Belokurov, Vasily; McMahon, Richard G; Auger, Matthew W; Lemon, Cameron A (2019-09-05)."Catalogues of active galactic nuclei from Gaia and unWISE data".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.489(4). Oxford University Press (OUP): 4741–4759.arXiv:1909.02010.doi:10.1093/mnras/stz2487.ISSN0035-8711.

- ^Storey-Fisher, Kate; Hogg, David W.; Rix, Hans-Walter; Eilers, Anna-Christina; Fabbian, Giulio; Blanton, Michael; Alonso, David (2024)."Quaia, the Gaia-unWISE Quasar Catalog: An All-Sky Spectroscopic Quasar Sample".AAS Journals.964(1): 69.arXiv:2306.17749.Bibcode:2024ApJ...964...69S.doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad1328.

- ^Bañados, Eduardo; et al. (6 March 2018). "An 800-million-solar-mass black hole in a significantly neutral Universe at a redshift of 7.5".Nature.553(7689): 473–476.arXiv:1712.01860.Bibcode:2018Natur.553..473B.doi:10.1038/nature25180.PMID29211709.S2CID205263326.

- ^Choi, Charles Q. (6 December 2017)."Oldest Monster Black Hole Ever Found Is 800 Million Times More Massive Than the Sun".Space.Retrieved6 December2017.

- ^Landau, Elizabeth; Bañados, Eduardo (6 December 2017)."Found: Most Distant Black Hole".NASA.Retrieved6 December2017.

- ^"Monster Black Hole Found in the Early Universe".Gemini Observatory.2020-06-24.Retrieved2020-08-31.

- ^Yang, Jinyi; Wang, Feige; Fan, Xiaohui; Hennawi, Joseph F.; Davies, Frederick B.; Yue, Minghao; Banados, Eduardo; Wu, Xue-Bing; Venemans, Bram; Barth, Aaron J.; Bian, Fuyan (2020-07-01)."Poniua'ena: A Luminousz= 7.5 Quasar Hosting a 1.5 Billion Solar Mass Black Hole ".The Astrophysical Journal Letters.897(1): L14.arXiv:2006.13452.Bibcode:2020ApJ...897L..14Y.doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab9c26.S2CID220042206.

- ^Maria Temming (January 18, 2021),"The most ancient supermassive black hole is bafflingly big",Science News.

- ^Schmidt, Maarten; Schneider, Donald; Gunn, James (1995). "Spectroscopic CCD Surveys for Quasars at Large Redshift. IV. Evolution of the Luminosity Function from Quasars Detected by Their Lyman-Alpha Emission".The Astronomical Journal.110:68.Bibcode:1995AJ....110...68S.doi:10.1086/117497.

- ^Chiu, Hong-Yee (1964)."Gravitational collapse".Physics Today.17(5): 21.Bibcode:1964PhT....17e..21C.doi:10.1063/1.3051610.

- ^"Hubble Surveys the" Homes "of Quasars".HubbleSite. 1996-11-19.Retrieved2011-07-01.

- ^"7. HIGH-ENERGY ASTROPHYSICS ELECTROMAGNETIC RADIATION".Neutrino.aquaphoenix. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-07.Retrieved2011-07-01.

- ^abShields, Gregory A. (1999)."A Brief History of Active Galactic Nuclei".The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.111(760): 661–678.arXiv:astro-ph/9903401.Bibcode:1999PASP..111..661S.doi:10.1086/316378.S2CID18953602.Retrieved3 October2014.

- ^"Our Activities".European Space Agency.Retrieved3 October2014.

- ^Matthews, Thomas A.;Sandage, Allan R.(1963)."Optical Identification of 3c 48, 3c 196, and 3c 286 with Stellar Objects".Astrophysical Journal.138:30–56.Bibcode:1963ApJ...138...30M.doi:10.1086/147615.

- ^Wallace, Philip Russell (1991).Physics: Imagination and Reality.World Scientific.ISBN9789971509293.

- ^"The MKI and the discovery of Quasars".Jodrell Bank Observatory.Retrieved2006-11-23.

- ^Schmidt Maarten (1963)."3C 273: a star-like object with large red-shift".Nature.197(4872): 1040.Bibcode:1963Natur.197.1040S.doi:10.1038/1971040a0.S2CID4186361.

- ^Gregory A. Shields (1999)."A Brief History of AGN. 3. The Discovery Of Quasars".

- ^Maarten Schmidt (1963)."3C 273: a star-like object with large red-shift".Nature.197(4872): 1040.Bibcode:1963Natur.197.1040S.doi:10.1038/1971040a0.S2CID4186361.

- ^Shields, G. A. (1999). "A Brief History of Active Galactic Nuclei".Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.111(760): 661.arXiv:astro-ph/9903401.Bibcode:1999PASP..111..661S.doi:10.1086/316378.S2CID18953602.

- ^S. Chandrasekhar(1964)."The Dynamic Instability of Gaseous Masses Approaching the Schwarzschild Limit in General Relativity".Astrophysical Journal.140(2): 417–433.Bibcode:1964ApJ...140..417C.doi:10.1086/147938.S2CID120526651.

- ^J. Greenstein;M. Schmidt (1964)."The Quasi-Stellar Radio Sources 3C 48 and 3C".Astrophysical Journal.140(1): 1–34.Bibcode:1964ApJ...140....1G.doi:10.1086/147889.S2CID123147304.

- ^G. K. Gray (1965)."Quasars and Antimatter".Nature.206(4980): 175.Bibcode:1965Natur.206..175G.doi:10.1038/206175a0.S2CID4171869.

- ^Lynch, Kendall Haven; illustrated by Jason (2001).That's weird!: awesome science mysteries.Golden, Colo.: Fulcrum Resources. pp. 39–41.ISBN9781555919993.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Santilli, Ruggero Maria (2006).Isodual theory of antimatter: with applications to antigravity, grand unification and cosmology.Dordrecht: Springer. p. 304.Bibcode:2006itaa.book.....S.ISBN978-1-4020-4517-2.

- ^Gregory A. Shields (1999)."A Brief History of AGN. 4.2. Energy Source".

- ^Keel, William C. (October 2009)."Alternate Approaches and the Redshift Controversy".The University of Alabama.Retrieved2010-09-27.

- ^Gunn, James E. (March 1971)."On the Distances of the Quasi-Stellar Objects".The Astrophysical Journal.164:L113.Bibcode:1971ApJ...164L.113G.doi:10.1086/180702.

- ^Kristian, Jerome (January 1973). "Quasars as Events in the Nuclei of Galaxies: the Evidence from Direct Photographs".The Astrophysical Journal.179:L61.Bibcode:1973ApJ...179L..61K.doi:10.1086/181117.

- ^abcThomsen, D. E. (Jun 20, 1987). "End of the World: You Won't Feel a Thing".Science News.131(25): 391.doi:10.2307/3971408.JSTOR3971408.

- ^"MUSE spies accreting giant structure around a quasar".eso.org.Retrieved20 November2017.

- ^de Swart, J. G.; Bertone, G.; van Dongen, J. (2017). "How dark matter came to matter".Nature Astronomy.1(59): 0059.arXiv:1703.00013.Bibcode:2017NatAs...1E..59D.doi:10.1038/s41550-017-0059.S2CID119092226.

- ^"Active Galaxies and Quasars – Double Quasar 0957+561".Astr.ua.edu.Retrieved2011-07-01.

- ^Nathan Secrest; et al. (Feb 25, 2021)."A Test of the Cosmological Principle with Quasars".The Astrophysical Journal Letters.908(2): L51.arXiv:2009.14826.Bibcode:2021ApJ...908L..51S.doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abdd40.

- ^Overbye, Dennis(24 March 2021)."The Most Intimate Portrait Yet of a Black Hole - Two years of analyzing the polarized light from a galaxy's giant black hole has given scientists a glimpse at how quasars might arise".The New York Times.Archived fromthe originalon 2021-12-28.Retrieved25 March2021.

- ^Grupen, Claus; Cowan, Glen (2005).Astroparticle physics.Springer. pp.11–12.ISBN978-3-540-25312-9.

- ^Hubble Surveys the "Homes" of Quasars.Hubblesite News Archive, Release ID 1996–35.

- ^abLambourne, Robert J. A. (2010).Relativity, Gravitation and Cosmology(Illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 222.ISBN978-0521131384.

- ^abTiziana Di Matteo; et al. (10 February 2005). "Energy input from quasars regulates the growth and activity of black holes and their host galaxies".Nature.433(7026): 604–607.arXiv:astro-ph/0502199.Bibcode:2005Natur.433..604D.doi:10.1038/nature03335.PMID15703739.S2CID3007350.

- ^"Quasars in interacting galaxies".ESA/Hubble.Retrieved19 June2015.

- ^Pierce, J S C; et al. (13 February 2023)."Galaxy interactions are the dominant trigger for local type 2 quasars".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.522(2): 1736–1751.arXiv:2303.15506.doi:10.1093/mnras/stad455.

- ^"Galaxy für Dehnungsstreifen"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on December 17, 2008.RetrievedDecember 30,2009.

- ^"Archived copy"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 2, 2010.RetrievedJuly 1,2011.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^"Astronomers solve the 60-year mystery of quasars – the most powerful objects in the Universe"(Press release). University of Sheffield. 2023-04-26.Retrieved2023-09-10.

- ^Peter J. Barthel (1989). "Is every Quasar beamed?".The Astrophysical Journal.336:606–611.Bibcode:1989ApJ...336..606B.doi:10.1086/167038.

- ^Bañados, Eduardo; et al. (6 December 2017). "An 800-million-solar-mass black hole in a significantly neutral Universe at a redshift of 7.5".Nature.553(7689): 473–476.arXiv:1712.01860.Bibcode:2018Natur.553..473B.doi:10.1038/nature25180.PMID29211709.S2CID205263326.

- ^"Bright halos around distant quasars".eso.org.Retrieved26 October2016.

- ^abGreenstein, Jesse L.; Schmidt, Maarten (1964)."The Quasi-Stellar Radio Sources 3C 48 and 3C 273".The Astrophysical Journal.140:1.Bibcode:1964ApJ...140....1G.doi:10.1086/147889.S2CID123147304.

- ^"New simulation shows how galaxies feed their supermassive black holes".sciencedaily.17 August 2021.Retrieved31 August2021.

First model to show how gas flows across universe into a supermassive black hole's center.

- ^Anglés-Alcázar, Daniel; Quataert, Eliot; Hopkins, Philip F.; Somerville, Rachel S.; Hayward, Christopher C.; Faucher-Giguère, Claude-André; Bryan, Greg L.; Kereš, Dušan; Hernquist, Lars; Stone, James M. (17 August 2021)."Cosmological Simulations of Quasar Fueling to Subparsec Scales Using Lagrangian Hyper-refinement".The Astrophysical Journal.917(2): 53.arXiv:2008.12303.Bibcode:2021ApJ...917...53A.doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac09e8.S2CID221370537.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^"Gravitationally lensed quasar HE 1104-1805".ESA/Hubble Press Release.Retrieved4 November2011.

- ^Dooling D."BATSE finds most distant quasar yet seen in soft gamma rays Discovery will provide insight on formation of galaxies".Archived fromthe originalon 2009-07-23.

- ^Nickolay Gnedin; Jeremiah Ostriker (1997). "Reionization of the Universe and the Early Production of Metals".Astrophysical Journal.486(2): 581–598.arXiv:astro-ph/9612127.Bibcode:1997ApJ...486..581G.doi:10.1086/304548.S2CID5758398.

- ^Limin Lu; et al. (1998). "The Metal Contents of Very Low Column Density Lyman- Alpha Clouds: Implications for the Origin of Heavy Elements in the Intergalactic Medium".arXiv:astro-ph/9802189.

- ^R. J. Bouwens; et al. (2012). "Lower-luminosity Galaxies Could Reionize the Universe: Very Steep Faint-end Slopes to the UV Luminosity Functions atz⩾ 5–8 from the HUDF09 WFC3/IR Observations ".The Astrophysical Journal Letters.752(1): L5.arXiv:1105.2038.Bibcode:2012ApJ...752L...5B.doi:10.1088/2041-8205/752/1/L5.S2CID118856513.

- ^Piero Madau; et al. (1999). "Radiative Transfer in a Clumpy Universe. III. The Nature of Cosmological Ionizing Source".The Astrophysical Journal.514(2): 648–659.arXiv:astro-ph/9809058.Bibcode:1999ApJ...514..648M.doi:10.1086/306975.S2CID17932350.

- ^Paul Shapiro;Mark Giroux (1987)."Cosmological H II regions and the photoionization of the intergalactic medium".The Astrophysical Journal.321:107–112.Bibcode:1987ApJ...321L.107S.doi:10.1086/185015.

- ^Xiaohu Fan; et al. (2001). "A Survey ofz> 5.8 Quasars in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. I. Discovery of Three New Quasars and the Spatial Density of Luminous Quasars atz~ 6 ".The Astronomical Journal.122(6): 2833–2849.arXiv:astro-ph/0108063.Bibcode:2001AJ....122.2833F.doi:10.1086/324111.S2CID119339804.

- ^"NASA Goddard Space Flight Center: News of light that may be from population III stars".Nasa.gov. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-04-16.Retrieved2011-07-01.

- ^abcPeterson, Bradley (1997).Active Galactic Nuclei.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-47911-8.

- ^Zakamska, Nadia; et al. (2003). "Candidate Type II Quasars from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. I. Selection and Optical Properties of a Sample at 0.3 <Z< 0.83 ".The Astronomical Journal.126(5): 2125.arXiv:astro-ph/0309551.Bibcode:2003AJ....126.2125Z.doi:10.1086/378610.S2CID13477694.

- ^Glikman, Eilat; et al. (2007). "The FIRST-2MASS Red Quasar Survey".The Astrophysical Journal.667(2): 673.arXiv:0706.3222.Bibcode:2007ApJ...667..673G.doi:10.1086/521073.S2CID16578760.

- ^Diamond-Stanic, Aleksandar; et al. (2009). "High-redshift SDSS Quasars with Weak Emission Lines".The Astrophysical Journal.699(1): 782–799.arXiv:0904.2181.Bibcode:2009ApJ...699..782D.doi:10.1088/0004-637X/699/1/782.S2CID6735531.

- ^"Dark Galaxies of the Early Universe Spotted for the First Time".ESO Press Release.Retrieved13 July2012.

- ^"ICRS Narrative".U.S. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-09.Retrieved2012-06-07.

- ^Myers, A.; et al. (2008). "Quasar Clustering at 25h−1kpc from a Complete Sample of Binaries ".The Astrophysical Journal.678(2): 635–646.arXiv:0709.3474.Bibcode:2008ApJ...678..635M.doi:10.1086/533491.S2CID15747141.

- ^Rincon, Paul(2007-01-09)."Astronomers see first quasar trio".BBC News.

- ^"Triple quasar QQQ 1429-008".ESO. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-02-08.Retrieved2009-04-23.

- ^Djorgovski, S. G.;Courbin, F.; Meylan, G.; Sluse, D.; Thompson, D.; Mahabal, A.; Glikman, E. (2007). "Discovery of a Probable Physical Triple Quasar".The Astrophysical Journal.662(1): L1–L5.arXiv:astro-ph/0701155.Bibcode:2007ApJ...662L...1D.doi:10.1086/519162.S2CID22705420.

- ^"Extremely rare triple quasar found".phys.org.Retrieved2013-03-12.

- ^Farina, E. P.; et al. (2013). "Caught in the Act: Discovery of a Physical Quasar Triplet".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.431(2): 1019–1025.arXiv:1302.0849.Bibcode:2013MNRAS.431.1019F.doi:10.1093/mnras/stt209.S2CID54606964.

- ^Hennawi, J.; et al. (2015). "Quasar quartet embedded in giant nebula reveals rare massive structure in distant universe".Science.348(6236): 779–783.arXiv:1505.03786.Bibcode:2015Sci...348..779H.doi:10.1126/science.aaa5397.PMID25977547.S2CID35281881.

- ^Blandford, R. D.;Narayan, R. (1992). "Cosmological applications of gravitational lensing".Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics.30:311–358.Bibcode:1992ARA&A..30..311B.doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.30.090192.001523.

- ^Henry, J. Patrick; Heasley, J. N. (1986-05-08). "High-resolution imaging from Mauna Kea: the triple quasar in 0.3-arc s seeing".Nature.321(6066): 139–142.Bibcode:1986Natur.321..139H.doi:10.1038/321139a0.S2CID4244246.

- ^"Hubble Resolves Two Pairs of Quasars".RetrievedApril 13,2021.

- ^"Webb's View Around the Extremely Red Quasar SDSS J165202.64+172852.3".October 19, 2023.

External links[edit]

- 3C 273: Variable Star Of The Season

- SKY-MAP.ORG SDSS image of quasar 3C 273

- Expanding Gallery of Hires Quasar Images

- Gallery of Quasar Spectra from SDSS

- SDSS Advanced Student Projects: Quasars

- Black Holes: Gravity's Relentless PullAward-winning interactive multimedia Web site about the physics and astronomy of black holes from the Space Telescope Science Institute

- Audio: Fraser Cain/Pamela L. Gay – Astronomy Cast. Quasars – July 2008

- Merrifield, Michael; Copland, Ed."z~1.3 – An implausibly large structure [in the Universe]".Sixty Symbols.Brady Haranfor theUniversity of Nottingham.

![These two NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope images reveal two pairs of quasars that existed 10 billion years ago and reside at the hearts of merging galaxies.[82]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Hubble_Resolves_Two_Pairs_of_Quasars.jpg/364px-Hubble_Resolves_Two_Pairs_of_Quasars.jpg)

![The quasar SDSS J165202.64+172852.3 images in the center and on the right present new observations from the JWST in multiple wavelengths to demonstrate the distribution of gas around the object. [83]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/26/Webb%27s_View_Around_the_Extremely_Red_Quasar_SDSS_J165202_64%2B172852_3_%28weic2217a%29.jpeg/356px-Webb%27s_View_Around_the_Extremely_Red_Quasar_SDSS_J165202_64%2B172852_3_%28weic2217a%29.jpeg)